Abstract

This paper focuses on the interaction of reasons and argues that reasons for an action may transmit to the necessary means of that action. Analyzing exactly how this phenomenon may be captured by principles governing normative transmission has proved an intricate task in recent years. In this paper, I assess three formulations focusing on normative transmission and necessary means: Ought Necessity, Strong Necessity, and Weak Necessity. My focus is on responding to two of the main objections raised against normative transmission for necessary means, in that they seem to give us reasons for buying tickets to plays we have no intention of seeing and that the principles give us the wrong result when the means are necessary but not sufficient. Even though these objections have been discussed previously, the counterarguments have so far relied on rejecting premises that the proponents of these objections are unlikely to concede. In this paper, I show how we may answer the objections in a way more likely to convince proponents of the objections. The result is an argument for a key aspect when it comes to understanding how reasons and ends-means normativity function. Normative transmission from ends to necessary means is not only interesting at the structural level, it is also possible to argue that it has implications for areas as diverse as philosophy of rationality, political philosophy and applied ethics.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

I assume there is some true normative transmission principle, though I do not know what it is (Broome 2013, p. 128).

In recent years, normative transmission principles have received considerable attention (Broome 2013; Kiesewetter 2015; Kolodny Forthcoming; Raz 2011; Scanlon 2014; Schroeder 2009). Suppose that you have reasons to φ and that the only way to φ is by means of ψing, where φing and ψing are two distinct actions. Intuitively, you then have at least some reason to ψ because it is the sole means of φing. Transmitting reasons in this way – getting a reason to do something because it is the necessary means for doing something else you originally had reason to do – seems to be one of the more common ways for how we acquire reasons to act. For example, you have a reason to buy a ticket to a play if, and because, you have reasons to attend the play and buying a ticket is necessary in order to do so.Footnote 1 The question addressed in this paper is whether, and if so how, reasons for performing an action transmit to the necessary means of performing that action.

The aim of this paper is to build on the progress already made in terms of normative transmission principles and to defend three principles by describing some of the ways in which normativity transmits from ends to necessary means. In section 2, I make some brief clarifying remarks on what this paper is not about and how we are to understand the notion of being a necessary means for something. Section 3 formulates three versions as to how normativity may transmit from ends to necessary means, while also offering an argument in favor of these versions in terms of the principles being derivable from the inheritance rule (OB-RM), a fundamental axiom in Standard Deontic Logic (SDL). Section 4 is devoted to outlining and answering two objections, Broome’s objection and Kolodny’s objection. Section 5, finally, concludes the discussion with some reflections on the philosophical advances associated with normative transmission.

2 Some Clarifications

A few clarifying words on terminology and the scope of this paper are in order. The paper is not a work on instrumental rationality (i.e., whether or not rationality requires us to intend the means to our ends). In the debate on rationality, there is normally no normative restriction with regard to our ends (Broome 2007; Kolodny 2005; Raz 2011). We do not need any reasons to go for the ends in the first place, and there are issues in that debate that are irrelevant for normative transmission. In this work, the ends we are interested in are actions we actually have reasons to do, or ought to do, which is why the issue of wide or narrow scope does not apply to the examples discussed here.Footnote 2

Unless otherwise specified, whenever I write that we have reasons to do something, I am talking about pro tanto reasons.Footnote 3 I also assume that what we ought to do is in some way connected to what we have reasons to do.Footnote 4 Having said that, I remain silent with regard to exactly how this connection should be understood. Nothing of importance hinges on how this connection is spelled out.

I limit the discussion to principles of normative transmission regarding necessary means, which is why I do not discuss principles that take sufficient means, or other types of means, as a relatum. This restriction is necessary, as transmission principles claiming that reasons are transmitted between an action we have reasons to do, or ought to do, and the sufficient means of performing that action pose their own set of unique problems; problems that deserve to be addressed in their own right in a separate paper. This restriction does not pose any theoretical difficulties, since there is no interdependency between the two types of principles: Acceptance of a normative transmission principle concerning necessary means does not to commit us to any particular view with regard to transmission principles concerning sufficient means, and vice versa.Footnote 5

In this paper, I adopt Kolodny’s (Forthcoming, p. 7) definition of necessary means:

Necessary means: ψ is a necessary means to φ if and only if:

-

1)

In every possible outcome at which one φs, one’s ψing helps to bring about one’s φing, and if one had not ψed, one would not have φed, and

-

2)

There is some possible outcome where one φs.

Kolodny’s definition combines a general definition of means and adds a necessity clause to the first condition. In Kolodny’s view, the phrase “helps to bring about one’s φing” in the first condition is supposed to be understood in terms of causing, constituting, satisfying preconditions of, preventing things that would prevent, and helping to do these things (Kolodny Forthcoming, p. 5).Footnote 6 To say that a means “helps to bring about one’s φing” must, according to Kolodny, be understood as saying that adopting the means makes it more probable that one φs. In Kolodny’s words “means probabilize the end to at least some degree” (Kolodny Forthcoming, p. 6). The second condition of our definition of necessary means ensures that there are no means to do the impossible.

3 The Principles

It is not exactly controversial to say that there are cases when our reasons for performing a specific action are dependent on that action being a means of performing some other action we have reasons to perform. A complete moral theory, however, must be able to provide a systematic explanation of these scenarios. Instantiations of this phenomenon are abundant and of particular interest when discussing applied ethics. For example, in the debate concerning the possibility of justified torture, it is often assumed that the fact (where it is a fact) that torture as a means of obtaining information may be a reason in favor of torture. If there is ever to be a reason for torture, this would be the reason, as it is a means for something else we have reasons to do.Footnote 7

Here, I present three principles describing different ways in which normativity may transmit from the end to the necessary means of that end. I borrow the definitions from Niko Kolodny (Forthcoming, p. 2).

-

Ought Necessity: If an agent, A, ought to φ and ψing is a necessary means of φing, then, because of that, A ought to ψ.Footnote 8

-

Strong Necessity: If there is a reason for one to φ and ψing is a necessary means of φing, then that is a reason, at least as weighty as one’s reason to φ, to ψ.Footnote 9

-

Weak Necessity: If there is a reason for one to φ and ψing is a necessary means of φing, then that is a reason, of some weight, to ψ.Footnote 10

As you can see, Strong Necessity entails Weak Necessity, but not the other way around. Whether or not Ought Necessity entails Strong Necessity or even Weak Necessity depends on one’s view concerning the link between ‘oughts’ and reasons.Footnote 11 At any rate, without being overly presumptuous, it is likely the case that Ought Necessity entails Weak Necessity, pace Horty (2012).

One of the main reasons for why we would want Ought Necessity, in addition to its intuitive appeal, is that we are able to show that it follows from Standard Deontic Logic (SDL). A vital axiom of SDL is the inheritance rule (OB-RM), which says that if ⊢ P ➔ Q then ⊢ OB(P) ➔ OB(Q) (McNamara 2014). Here, “OB(P)” is supposed to be read as P being obligatory. We can derive Ought Necessity from OB-RM given the reasonable assumption that if Q is a necessary means for P, then (doing) P implies (having done) Q. As shown below:

-

(1)

(⊢ P ➔ Q)((⊢ OB(P) ➔ OB(Q)). (OB-RM)

-

(2)

Nec-M(Q,P) ➔ (P ➔ Q). (Stipulation: If Q is a necessary means of P, then P implies Q)

-

(3)

Nec-M(Q,P). (Assumption: Q is a necessary means of P)

-

(4)

P ➔ Q. (From 2, 3)

-

(5)

OB(P). (Assumption)

-

(6)

OB(P) ➔ OB(Q). (From 1, 4–5)

-

(7)

OB(Q) (From 5 to 6).

-

(8)

Nec-M(Q,P) & OB(P) ➔ OB(Q) (From 1 to 7).

To be sure, few philosophers accept all of the axioms of Standard Deontic Logic. Nonetheless, it is still the case that, ceteris paribus, a view that can retain all, or at least most, of SDL is preferable over one that retains a smaller number of the axioms.Footnote 12 As we can easily show, since denying Ought Necessity means that you need to reject OB-RM, we would need very good reasons for rejecting Ought Necessity.

If we further assume that what we ought to do is somehow related to our reasons for doing so, more precisely if we assume that it cannot be the case that we ought to do something if we have stronger reasons for not doing so than for doing so, then the argument from Standard Deontic Logic naturally extrapolates itself to Strong Necessity. Suppose that we ought to P and that Q is a necessary means of P. According to Ought Necessity, we then ought to Q. If the transmitted reasons to Q are not as strong as the reasons to do P, we are susceptible to the following counter-example: Suppose that the transmitted reason to Q is outweighed by reasons to not Q. Given the assumptions concerning the links between reasons and ‘oughts’, it is not the case that we ought to Q. Such a result would be in conflict with Ought Necessity. To avoid this result, we must assume Strong Necessity or accept that we sometimes ought to do things despite the fact that we have stronger reasons for not doing these things. Given that Weak Necessity follows from Strong Necessity, and according to most views from Ought Necessity, the argument from Standard Deontic Logic additionally lends itself to Weak Necessity.

4 The Objections

I here discuss two objections against Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity, where only the first objection may be said to target Weak Necessity. The first objection stems from John Broome and concerns cases where one has no intention of achieving the end, even if one adopts some of the means (Broome 2013, p. 126). The second objection is from Niko Kolodny, where he claims that Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity provide us with unintuitive results, and that the strength of the reason transmitted should correspond to the likelihood of the necessary means resulting in the end (Kolodny Forthcoming).

4.1 Broome’s Objection

Broome uses the following example as an argument against Ought Necessity:

Suppose that prudence requires you to see your doctor, and the only way of doing so is to take a day off work. (The importance of seeing your doctor outweighs the bad consequences of taking a day off work.) According to End to Means Transmission [Ought Necessity], prudence requires you to take a day off work. But suppose you have no intention of seeing your doctor, and you will not do so even if you take a day off work. You will simply sit around feeling anxious. Then it is implausible that prudence requires you to take a day off work (2013, p. 126).

Even though Broome here talks about what prudence requires, the structure of the example is quite straightforward: There is something you ought to do and there is a necessary, but not sufficient, means that you may adopt. However, even if you adopt the necessary means, you will not do the thing that you ought to do, as you have no intention of adopting the additional means that would be required in order to do what you ought to do. In such a scenario, Broome argues, the ‘ought’ is not transmitted from the end to the means. The underlying intuition is that it would be a waste to take a day off and then not go to the doctor or, for instance, buying a ticket to a train you will not take regardless of whether you buy the ticket or not.

Once the structure of Broome’s argument is clarified, we may note, with the help of Kiesewetter (2015), that Broome’s example is just a version of Frank Jackson and Robert Pargetter’s famous Professor Procrastinate example (1986). The condensed version of this example is that Professor Procrastinate is given the option of writing a review; if he accepts writing a review, he will procrastinate and fail to write it. It is not impossible for Professor Procrastinate to write the review – he simply will not do it. If he does not accept, then someone else will write it. Jackson and Pargetter argue in favor of the position known as Actualism, which says that Professor Procrastinate should not accept writing the review, because what would actually happen if he were to accept to do so is that he would not write the review, which is worse than what will actually happen if he were to choose not to accept to write it. One answer to Broome’s objection, championed by (Kiesewetter 2015), is to deny Actualism and instead argue for the rival view of Possibilism. Applied to the case of Professor Procrastinate, Possibilism roughly says that Professor Procrastinate ought to accept the offer to write the review because it is possible, and sufficiently within his control, to write it. Consequently, Kiesewetter’s response to Broome’s objection is that you in fact ought to take a day off, because if you do, it is possible, and sufficiently within your control, that you in fact visit the doctor.

The problem with rejecting Actualism in favor of Possibilism as a way of dealing with Broome’s objection is that this is an answer unlikely to convince anyone swayed by Broome’s argument in the first place.Footnote 13 While I am sympathetic towards Kiesewetter’s line of reasoning, I think that there is an argument that Broome and proponents of Actualism might be more responsive to.

I believe that in Broome’s example, it is questionable whether taking a day off actually qualifies as a means of visiting the doctor given the fact that we assume Actualism. Prima facie, it might appear to be a necessary means, but I would argue that in this instance, we are deceived by appearances. Given the story told by Broome, it is unquestionably necessary that you take a day off in order to visit the doctor. The reason why I think that taking a day of work is not a necessary means for you to visit the doctor is the following: Taking a day off work, given that you in fact will not see the doctor, does not in any way help bring about an outcome where you visit the doctor. The fact that “helping to bring about the end” is a necessary condition for being a necessary means thus means that taking a day off work does not qualify as a necessary means for visiting the doctor. Of course, if you are undecided but leaning towards not visiting the doctor even if you take a day off, then it might be the case that taking a day off helps to bring about you visiting the doctor. However, based on the actualist picture painted in Broome’s description of the case, I fail to see how taking a day off in any way helps bring about you seeing the doctor.

Given Actualism, claiming that taking a day off work in Broome’s scenario is not a means for visiting the doctor is quite controversial and we need to spend a bit more time on this question. Taking a day off is a necessary part of any plan to visit the doctor, which, if completed, would entail, or at least make it more likely, that you visit the doctor. So taking a day off could be a necessary means. The issue is whether taking a day off work in any way helps to bring about that you visit the doctor given the fact that you will not actually visit the doctor. Given that we know that you will not visit the doctor regardless of whether or not you take a day off, we can rule out that it causes you to visit the doctor. Taking a day off is not constitutive of visiting the doctor, so it is not a matter of constitution. It might, however, count as satisfying a pre-condition, or at least preventing something that would have prevented you from visiting the doctor. The problem is that given Actualism and that you have no intention of visiting the doctor, and in fact will not go, it is hard to see in what way taking a day off makes the end more likely. Taking a day off does not make it more probable that you will visit the doctor, and therefore fails to help to bring about that you visit the doctor; in which case taking a day off cannot be a necessary means for visiting the doctor. If we for instance adopt a frequency interpretation of probability, what is the frequency of you visiting the doctor when you actually will not visit the doctor conditionalized on you taking a day off? Trivially, the frequency of doing anything in a scenario where you in fact will not do so is zero. I do not see how any other interpretation of probability would alter this result, at least not without altering the original example in such a way that it is no longer clear that it is not the case that you ought to take a day off. Stephen J. White seems to share the idea that taking a day off in no way helps to bring about that you visit the doctor:

Under the circumstances it would hardly be credible to explain your taking the day off as something you do in order to see your doctor. Indeed, it’s not clear why—for what purpose—you would be taking the day off (2017, p. 732).Footnote 14

Broome faces the following dilemma: he either has to concede that taking a day off does not, in his objection, qualify as a means – thereby no longer being a genuine objection against Ought Necessity – or he must affirm that it is a means, in which case it cannot be the case that you will not visit the doctor. The intuition that taking a day off will be a waste cannot be as prevalent if we assume that taking a day off work is actually a means for going to the doctor, (i.e., if taking a day off helps to bring about that you go to the doctor). Subsequently, it is no longer clear why the requirement would not transmit from the end of visiting the doctor.

4.2 Kolodny’s Objection

What may be the chief objection to Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity has been put forward by Kolodny (Forthcoming). He believes that the degree of strength of the reasons transmitted from ends to necessary means depends on how much more likely the end becomes by adopting the means. He bases his argument on the following example of Unlucky and Lucky and whether they ought to adopt, and have equally strong reasons for adopting, the necessary means of taking a taxi in order to save an antique on a porch:

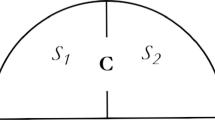

Consider Lucky and Unlucky, who occupy parallel universes. Each has an antique sitting on his front porch, which the rain threatens to ruin. A necessary means to saving the antique is taking a taxi back home. There is reason to refrain from taking the taxi; it costs money, say $20. But this cost is outweighed by the value of the antique, say $100. The only difference in their situations is that in Lucky’s universe, the rain will be slow in coming, and so he is very likely to get home in time, if he takes the taxi: say the probability is .9. In Unlucky’s universe, by contrast, he is extremely unlikely to get home in time, even if he takes it: the probability is .1 (Kolodny Forthcoming, pp. 7 - 8).

Kolodny holds the view that since things would be the same in the relevant aspects if Unlucky were to save the antique as if Lucky were to save the antique, their reasons for saving the antique are equally strong (Kolodny Forthcoming, p. 8).Footnote 15

Kolodny believes that while Lucky ought to take the taxi, it is not the case that Unlucky ought to take the taxi, nor does Kolodny view Lucky and Unlucky as having equally strong reasons to take the taxi. According to Ought Necessity, they both ought to take the taxi, and according to Strong Necessity, their reasons for taking the taxi are equally strong. Kolodny rejects the idea that Unlucky ought to take the taxi and that Unlucky’s reason for taking the taxi is as strong as that of Lucky. He therefore denies Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity. Kolodny does not reject Weak Necessity, as he believes that Unlucky has some reason for taking the taxi (Kolodny Forthcoming, p. 25). Kolodny’s rejections of Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity, however, might be premature.

One ill-advisable way to answer Kolodny’s objection would be to bite the bullet and claim that Lucky and Unlucky have equally strong pro tanto reasons for taking the taxi stemming from their equally strong reasons for saving the antique, but that Unlucky has stronger reasons against taking the taxi compared to Lucky. The reasons against taking the taxi are explained by appealing to a cost-avoidance principle. Such a principle might claim that the fact that there is a 10% risk that Lucky will not save the antique and only suffer the additional cost of adopting the means is a reason against adopting the means, and that the fact that there is a 90% risk that Unlucky will not save the antique and only suffer the additional cost of adopting the means is a reason against adopting the means. In this case, the 90% risk results in a stronger reason against taking the taxi compared to the 10% risk, thereby explaining the difference in the all-things-considered reason for taking the taxi in the two cases. This line of reasoning, however, is unable to explain why Unlucky ought to save the antique, and yet why it is not the case that he ought to take the taxi.

Another option for proponents of Strong Necessity and Ought Necessity is to reject Kolodny’s assumption that Lucky and Unlucky reasons for saving their antiques are equally strong and, as I believe we should, reject that any of them ought to save their antiques.

But why would this be the case? The antiques are equally valuable in the scenarios, and if the antique is actually saved, things will be the same for both Lucky and Unlucky. A possible line of inquiry is to ask what saving the antique amounts to. Plausibly, Unlucky succeeds in saving the antique when the antique is safe from the rain. But when does the action begin? One might say that Unlucky starts saving the antique when he gets into the cab, continues saving the antique when he exits the cab, lifts the antique off the porch and brings it inside. But even if taking the taxi is constitutive of saving the antique, in our definitions of necessary means we have included that of constituting. Since I find no good reason as to why the transmission principles analyzed would not extend to this type of relation, it seems like a non-starter trying to answer Kolodny through this maneuver.

Kolodny’s argument for thinking that Unlucky ought to save the antique is stated as follows: “Lucky ought to save the antique. As far as saving the antique is concerned, Unlucky’s situation is the same. If Unlucky saves the antique, things will be exactly as they are if Lucky saves it” (Kolodny Forthcoming, p. 8).

In discussing whether or not Lucky and Unlucky ought to save the antique, it seems reasonable to first address the question of whether either of the two actually can save it, in a morally relevant sense of ‘can’. They can adopt the means necessary for saving the antique, but the necessary means available to them are insufficient for guaranteeing that they actually will save the antique.

Let us assume that despite the favorable odds, Lucky takes the taxi but does not manage to get home in time to save the antique. In this scenario, it is obviously false to claim that Lucky succeeded in saving the antique. According to Kolodny, Lucky therefore failed to do what he ought to have done. Since saving the antique does not seem to be supererogatory, Lucky would appear to be open to criticism for not doing what he ought to have done, and on some views he might even be blameworthy.Footnote 16 The charge that Lucky failed to do what he ought to have done seems somewhat unfair. Lucky did all he could to save the antique. The answer to this counterintuitive conclusion is to insist that given a sensible reading of ‘ought implies can’, it was simply not the case that Lucky ought to have saved the antique. The only thing we can morally require of Lucky is not that he ought to save the antique, but rather that he ought to try his best to save the antique.

There is no need for us to get bogged down in a discussion concerning the correct way of understanding what we mean by ‘can’ in ‘ought implies can’; the only thing we need is that at least the following trivial-sounding principle is true:

Test.

If an agent, A, tries her best to φ and yet fails to φ then she could not do it in the sense relevant to ‘ought implies can’.Footnote 17

The reason why the test specifies that A tries her best is to avoid the inclusion of cases where the agent makes a half-hearted attempt she knows will not be enough to cases that do not satisfy the test. It is surprisingly complicated to give a proper characterization of what it means to try one’s best. Such a characterization calls for an analysis of what it means to try to do something and what it means to try your best to do something. These questions open up for several intricate discussions I am unable to do proper justice in this work. All I am able to offer in this work is a rough negative characterization. Trying one’s best is something more than a half-hearted attempt. Most likely, trying one’s best to φ does not have to be identical to what oneself believes is trying one’s best, as agents can have false beliefs concerning the consequences of certain means, and so forth.Footnote 18 Nonetheless, I believe that we have some sort of intuitive grasp of the idea that if one really tried one’s best in the sense that one took the objectively optimal route towards φ and yet fails to φ, then φing was not an action one could perform in the sense of ‘can’ we are after in in ‘ought implies can’.Footnote 19

The following example helps to illustrate just how unreasonable it is to claim that Lucky ought to save the antique: Lucky is given the option of buying a lottery ticket that costs $20. The ticket offers a 90% probability of winning $100 and a 10% probability of losing, so the expected return is $70. Unlucky is given the option of buying a lottery ticket that costs $20. This ticket offers a 10% probability of winning $100 and a 90% probability of losing, so the expected return is just -$10. Winning $100 in this scenario is the equivalent of saving the antique in Kolodny’s original scenario. According to Kolodny, Lucky ought to win $100 and therefore ought to buy a lottery ticket.Footnote 20 Kolodny would furthermore claim that Unlucky ought to win $100, since if Unlucky were to win, things would be the same as if Lucky wins. Given that Kolodny would assert that Unlucky also ought to win this means that Unlucky ought to buy a lottery ticket then according to Ought Necessity Unlucky ought to buy a lottery ticket. Kolodny would also say it is obviously false that Unlucky ought to buy the lottery ticket because Unlucky is very likely to lose 20$. A problem with this description arises from the phrase “Lucky ought to win $100.” Winning would surely benefit him, but whether he wins is out of his control. The only thing he can do is to buy the lottery ticket and hope for the best. All he can do is try to win, and therefore all he possibly ought to do is try to win. To say that Lucky ought to win $100 is as incoherent as saying that Lucky ought not to have a headache. It would be good for Lucky not to have a headache, so he ought to do what he can in order to avoid this (e.g., drinking water, getting enough sleep, and so forth). In short, what Lucky ought to do is try not to get a headache.

The same applies to Kolodny’s original example. The answer to Kolodny’s objection is thus that no reason or ought transmits from the end of saving the antique to that of taking the taxi for either of them, because neither Lucky nor Unlucky have any reason or moral obligation to save the antique. Lucky and Unlucky do not have sufficient control over whether the antique is ultimately saved. Nonetheless, it is probably the case that Lucky ought to try to save the antique. For simplicity, let us assume that taking the taxi is a necessary means for trying to save the antique, and that Lucky therefore ought to take the taxi.

The following question then arises: Is it also the case that Unlucky ought to try to save the antique? I believe that, given what we have been told about the case, the answer is: No, it is not the case that Unlucky ought to try to save the antique. He is likely to lose out if he were to try, and because of this I believe that it is quite plausible that it is the case that Unlucky ought to not try to save the antique.Footnote 21 This way of determining the strength of reasons, and whether one ought to try to do something, seems to be present in Kolodny (Forthcoming, p. 8). Since it is not the case that Unlucky ought to try to save the antique, it should come as no surprise that it is not the case that Unlucky ought to take the taxi. Of course, Unlucky still has some reasons for trying to save the antique, and these reasons transmit to taking the taxi. Note, however, that Unlucky’s reasons for trying to save the antique are weaker than those of Lucky, which means that everything is as it ought to be when it turns out that Unlucky has weaker reasons for taking the taxi compared to Lucky.

We thereby manage to respect Kolodny’s intuitions in the case of taking the taxi. We do so while retaining the intuitive principles of Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity.Footnote 22

5 Conclusion

In this paper I have shown that the objections raised so far against any of the normative transmission principles for necessary means may be counteracted. However, the explanatory power of Ought Necessity and Strong Necessity should not be overstated. In addition to these principles, we also need principles that pick out the best means when there is a multitude of means available and the only necessary means is to adopt at least one of the multitude of means. For instance, should I go to Oxford by car, bus or train? The only necessary means is satisfying the disjunction of car, bus or train but obviously satisfying the disjunction can be done in a better or worse ways.

What about Weak Necessity? In this paper, only Broome’s objection could be construed as also addressing Weak Necessity. If Broome’s challenge is indeed met, regardless of the low probability that Unlucky will save the antique, even Kolodny agrees that Unlucky still has some reason (for trying) to save the antique.

If the necessity principles are true, as I believe I have shown that they probably are, then they give us a more succinct and systematic way of understanding some of the interaction of reasons and that of ‘oughts’ – an understanding vital not only for meta-ethics, but also for normative and applied ethics.

Notes

Henceforth, by an “end,” I have an action in mind that someone has a reason to do. This might not be the standard way of understanding an “end,” but since I in this paper merely focus on reasons for actions, and actions that we ought to do, I do not think that this usage will lead to any misunderstanding. How other reasons, such as reasons for attitudes or beliefs function, is outside the scope of the paper.

On a wide scope formulation of instrumental rationality, rationality requires us to either adopt the means or give up the end. On a narrow scope formulation of rationality, rationality requires us to adopt the means but does not allow us to give up the end (Broome 2007).

In the literature, there is some controversy as to how to define a pro tanto reason. For attempts to understand pro-tanto reasons see (Broome 2013; Dancy 2004; Hurley 1989; Scanlon 1998). For our present purposes, it is sufficient to provide a minimal definition: A pro tanto reason is something that counts in favor of doing something, albeit not necessarily settling the matter. To say that R is a pro tanto reason to φ is to say that R is a normative feature of the situation that may in some sense be weighed against, and outweighed by, other pro tanto reasons.

Throughout the paper, I use ‘ought’ and ‘moral obligation’ synonymously.

One might feel a bit uneasy when it comes to talking of ‘transmission’ as if it is introducing a hitherto unknown and mysterious relation. However, this kind of unease may be put to rest. Following Jonathan Way, we should understand “there is a reason to φ, and since ψing is a [necessary] means to φ there is a reason to ψ” as saying that “If R is a reason to φ, then the fact that R, and that ψing is a [necessary] means to φ, is a reason to ψ” (Way, 2012). For example, if the fact [The play is enjoyable] is a reason to see the play, then the complex fact that [The fact that the play is enjoyable, and buying a ticket is a necessary means to seeing the play] is a reason to buy a ticket. As such, there are no mysterious metaphysical assumptions underlining talk of transmission, and hence no reason to feel uneasy when it comes to talking about transmission.

It should be noted that Kolodny does not claim that this list is exhaustive. However, while it is not exhaustive, it is quite wide. Take constituting for instance: under this definition, going for a jog is constitutive of exercising but also a means (albeit in most situations not a necessary means) of exercising.

There is common objection in connection to the torture example that I do not discuss in detail in this paper, as it is one of the few objections that no one in the debate subscribes to. This is the so-called “Evil Means Objection.” The objection goes as follows: If we ought to reach some end, and the necessary means of doing so is “evil,” then the transmission principles seem to entail that we ought to, or have reasons to, do evil things. This objection may be found in the common sense expression “the end does not justify the means.” A charitable interpretation of the principle is that “the end does not always justify the means.” Sometimes, you have a stronger reason for not adopting the means than for achieving the end, and sometimes you ought to not adopt the necessary means. Then, of course, it is false that you ought to achieve the end in the first place. For a discussion regarding this objection, see Kolodny (Forthcoming, p. 26) and Bedke (2009, p. 684). Reasons and moral obligations transmit to (morally) costly means. On the other hand, this objection should not be taken lightly. For example, some Kantians might hold the view that some actions are always impermissible. So let us assume that you ought to save two individuals in need, but that a necessary means of doing so is that you kill an innocent person. At the same time, killing of an innocent person is always impermissible. Such a Kantian would either have to deny that you ought to save the two individuals in need, deny Ought Necessity, or allow for genuine moral dilemmas.

Similar principles may be found, such as: “If X has an objective reason to do A and to do A X must do B, then X has an objective reason to do B of equal weight to X’s objective reason to do A” (Schroeder 2009, p. 245) and “(T2) If you have a reason to do A and doing B is a necessary means to doing A, you have a reason to do B which is at least as strong as your reason to do A” (Way 2010, p. 225).

With the exception of Kolodny I have not been able to find any previous writers explicitly endorsing Weak Necessity.

Some readers may correctly note that the principles do not necessarily give unique action guidance when the necessary means consists of satisfying a disjunction (e.g., in order to get to Oxford from London, I can either take the bus, the train, or the car). None of the separate means are necessary on their own. The necessary means of travelling to Oxford is that you adopt one of the means. Since the principles presented here only deal with necessary means, they will not tell you that you have reasons to, or ought to, take the best means in a uniquely action guiding sense, but only that you have reasons to, or ought to, take the necessary means – remaining silent on the issue of how I ought to satisfy the disjunction of taking the bus, the car, or the train. I do not believe that this represents a problem for the principles. A complete theory of ends-means normativity must be able to explain exactly which means we should take, but just the fact that the three principles in question are not sufficient for a complete theory of ends-means normativity cannot be used as an argument against the principles.

Given the fact that I argue in favor of the normative transmission principles by utilizing the inheritance rule (OB-RM) within deontic logic, it should come as no surprise that the principles run into the same paradoxes and problems as OB-RM, in particular the Good Samaritan Paradox (Prior 1958). The Good Samaritan Paradox, roughly, is that the fact that Alex is helping Samantha who has been robbed entails that Samantha has been robbed. Therefore, according to OB-RM, if Alex ought to help Samantha who has been robbed, then we get that Samantha ought to have been robbed. Since problems associated with OB-RM require a more general discussion and solution than what I am able to provide in this paper without going off on an extensive tangent, I hereby refer to Boer et al. (2012); Castañeda (1981); Prior (1958); Tomberlin (1981) for a discussion concerning the problems with OB-RM and potential solutions to the associated problems. However, one might bring forward an objection similar in spirit to the Good Samaritan Paradox in connection to this discussion: We assumed that satisfying a pre-condition may be a necessary means of something. If A at t2 ought to φ, and a precondition for that is that A at t1 ψied, then it seems as if A ought to ψ. If we assume that φing is giving back what A stole, and ψing is stealing, we seem to get the result that A ought to steal. First off, of course it cannot be the case that A at t2 has a reason to do anything at t1, as this is impossible. The interesting question here is whether the argument entails that A at t1 ought to φ. The answer to this question is a firm no. That A ought to φ at t1 is merely conditional (i.e., if ψ then OB(φ)), and the antecedent of the conditional is not satisfied. Ψing is a pre-condition for A having the obligation to φ, but in general we do not have a reason to make sure that hypothetical obligations, or hypothetical reasons for that matter, become actual. Nor does the normative transmission principles imply that we do. The principles are only concerned with actions for which we have obtained reasons to perform.

For instance, see (White 2017).

To be fair, White does not mention the purposelessness of taking the day off in connection to whether or not taking the day off should count as a means, but rather in connection to an argument against the notion that the reason for you to visit the doctor does not constitute a reason for taking a day off.

Kiesewetter (2015) answers the objection by arguing that Kolodny’s example rests on Actualist assumptions that should be rejected on independent grounds. I have nothing original to add to Kiesewetter’s discussion, other than that it is unlikely to convince any Actualists. This is not to say that Kiesewetter deems all forms of Actualism as necessarily being incompatible with Strong Necessity and Ought Necessity, but merely that Jackson and Pargetter’s version of Actualism as presented (1986) is incompatible with Strong Necessity and Ought Necessity.

It might of course be that saving the antique is indeed supererogatory. However, in principle, it is possible to advance a new example where the source action is not supererogatory while retaining the same argumentative structure as that in Kolodny’s original example.

This might depend on one’s view in Jackson-style cases, such as the doctor who can give one of three possible drugs to a sick patient. One of the drugs will partially cure the patient. As far as the other two drugs are concerned, one will completely cure the patient and one will kill the patient, and the doctor does not know which one is which. If one is more objectivist-leaning, one would prescribe giving the patient the life-saving drug, and if one is more subjectivist-leaning, one would prescribe the drug the doctor knows will partially cure the patient.

To be sure, if one understands “trying one’s best” in more subjective terms of what the agent believes, or given the available evidence, then the Test might be false. Assuming a more objectivist reading, however, it seems very unlikely that the Test is false.

I am well aware of the fact that the phrase “Lucky ought to win $100” sound odd, but given Kolodny’s description of the case of Lucky and Unlucky, I believe that it is no less odd than the phrase “Lucky ought to save the antique.”.

A potential concern might be the following: if he ought to not try, does it follow that Unlucky ought to not take the taxi? That depends. At first glance, one would perhaps be inclined to say that it follows that Unlucky ought to not take the taxi. If Unlucky ought to not try to save the antique, he ought to not take the taxi, because that would count as trying to save the antique. But this is a mistake for two reasons. First, it might be the case that Unlucky ought to take the taxi to visit his next-door neighbor Bucky. Second, in order for Unlucky’s act of taking the taxi to count as him trying to save the antique, he would have to take the taxi with the intention of taking it as a means to save the antique. Taking the taxi to visit his neighbor Bucky without any intention to save the antique does not count as Unlucky trying to save the antique. Just as me walking out of my office does not count as me trying to go to Italy, even though walking out of my office is a necessary means for me to go to Italy.

In addition, and this is a bit more controversial and nothing I am able to address in this paper, if one were to claim that your obligation is only to try to go and see your doctor, we can see why it is not the case that you ought to take a day off given that you have no intention of visiting the doctor anyhow. This is because if you take the day off with no intention of seeing your doctor, it does not seem as if taking a day off counts as trying to see your doctor just as me walking out of my office does not count as trying to go to Italy when I have no intention of going to Italy.

References

Austin, J. (1956). Ifs and cans. In J. W. Urmson, G (Ed.), Philosophical papers. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Reprinted from: 1979).

Bedke, M. (2009). The iffiest oughts: A guise of reasons account of end-given conditionals. Ethics, 119(4), 672–698.

Boer, M., Gabbay, D. M., Parent, X., & Slavkovic, M. (2012). Two dimensional standard deontic logic [including a detailed analysis of the 1985 Jones–Pörn deontic logic system]. Synthese, 187(2), 623–660.

Broome, J. (2007). Wide or narrow scope? Mind, 116(462), 359–370.

Broome, J. (2013). Rationality through reasoning. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carlson, E. (1999). The Oughts and cans of objective consequentialism. Utilitas, 11(1), 91–96.

Castañeda, H.-N. (1981). The paradoxes of deontic logic: The simplest solution to all of them in one fell swoop. In R. Hilpinen (Ed.), New studies in deontic logic: norms, actions, and the foundations of ethics (pp. 37–85). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Dahl, N. O. (1974). Ought implies can and deontic logic. Philosophia, 4(4), 485–511.

Dancy, J. (2004). Ethics without principles. Oxford: Clarendon.

Horty, F. J. (2012). Reasons as defaults. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howard-Snyder, F. (1997). The rejection of objective consequentialism. Utilitas, 9(02), 241–248.

Hurley, S. L. (1989). Natural reasons : Personality and polity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, F., & Pargetter, R. (1986). Oughts, options, and actualism + the exploration and defense of actualism. Philosophical Review, 95(2), 233–255.

Kiesewetter, B. (2015). Instrumental normativity: In defense of the transmission principle. Ethics, 125(4), 921–946.

King, A. (2014). Actions that we ought, but Can't. Ratio, 27(3), 316–327.

Kolodny, N. (2005). Why be rational? Mind, 114(455), 509–563.

Kolodny, N. (Forthcoming). Instrumental reasons. In D. Star (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of reasons and normativity. Oxford University Press.

McNamara, P. (2014). "Deontic logic". In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Standford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2014 ed.): Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/logic-deontic/.

Prior, A. N. (1958). Escapism: The logical basis of ethics. In A. I. Melden (Ed.), Essays in moral philosophy (pp. 135–146). Seattle: University of Washingtonn Press.

Raz, J. (2011). From normativity to responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scanlon, T. M. (1998). What we owe to each other. Belknap: Cambridge.

Scanlon, T. M. (2014). Being realistic about reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, M. (2009). Means-end coherence, stringency, and subjective reasons. Philosophical Studies, 143, 223–248.

Stocker, M. (1971). Ought' and 'can. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 49(3), 303–316.

Tomberlin, J. E. (1981). Contrary-to-duty imperatives and conditional obligation. Noûs, 15(3), 357–375.

Vranas, P. B. M. (2007). I ought, therefore I can. Philosophical Studies, 136(2), 167–216.

Way, J. (2010). Defending the wide-scope approach to instrumental reason. Philosophical Studies, 147(2), 213–233.

Way, J. (2012). Transmission and the Wrong Kind of Reason. Ethics 122(3), 489–515.

White, S. J. (2017). Transmission failures. Ethics, 127(3), 719–732.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to David Alm, Toni Rønnow-Rasmussen, and Benjamin Kiesewetter for helpful feedback on previous drafts of this paper. For productive conversations, thanks to Henrik Andersson, John Broome, Andrés Garcia, Wlodek Rabinowicz, and those in attendance for a presentation of a previous draft of this paper at the 2015 OZSW Conference, and at the higher seminar in practical philosophy, Lund 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Werkmäster, J.G. Normative Transmission and Necessary Means. Philosophia 47, 555–568 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-018-9976-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-018-9976-7