Abstract

This study investigated the soil pollution level and evaluated the phytoremediation potential of 25 native plant species on a former gold mine-tailing site in Ghana. Plant shoots and associated soil samples were collected from a tailing deposition site and analyzed for total element concentration of As, Hg, Pb, and Cu. Soil metal(loid) content, bioaccumulation factor (BAFshoots), and hyperaccumulator thresholds were also determined to assess the current soil pollution level and phytoextraction potential. The concentration of As and Hg in the soil was above international risk thresholds, while that of Pb and Cu were below those thresholds. None of the investigated plant species reached absolute hyperaccumulator standard concentrations. Bioavailability of sampled metal(loid)s in the soil was generally low due to high pH, organic matter, and clay content. However, for Cu, relatively high bioaccumulation values (BAFshoots > 1) were found for 12 plant species, indicating the potential for selective heavy-metal extraction via phytoremediation by those plants. The high levels of As at the study site constitute an environmental and health risk but there is the potential for phytoextraction of Cu (e.g., Aspilia africana) and reclamation by afforestation using Leucaena leucocephala and Senna siamea.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Heavy metal and metalloid pollution has become one of the most serious environmental problems worldwide (Wuana & Okieimen, 2011; Tchounwou, Yedjou, Patlolla, & Sutton, 2012; Tóth, Hermann, Szatmári, & Pásztor, 2016). Industrial processes, traffic, and mining are the main diffuse or point sources for the contamination of the environment (Prasad & Freitas, 2003; Bradl, 2005; Alloway, 2013). High toxicity, non-biodegradability, and accumulation in the food chain make metal(loid)s hazardous for the environment and human health (Singh, Gautam, Mishra, & Gupta, 2011; Ali, Khan, & Sajad, 2013). Consequently, it becomes apparent that there is a great need for resource protection and health security regarding heavy metal(loid)s.

Traditional solutions like excavation of contaminated materials and chemical as well as physical treatments are costly and might cause additional secondary pollution (Mulligan, Yong, & Gibbs, 2001; Yoon, Cao, Zhou, & Ma, 2006). In contrast, phytoremediation, a technique of using plants to reduce or remove hazardous substances from the environment can offer a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative (Ali et al., 2013; Dadea, Russo, Tagliavini, Mimmo, & Zerbe, 2017), particularly for the developing world (Robinson et al., 2003; Eraknumen & Agbontalor, 2007). Among phytoremediation technologies, the concept of phytoextraction is considered the most efficient and sustainable strategy for decontamination of metal(loid)-polluted soils (Ali et al., 2013). By the use of “hyperaccumulators”, i.e., plants that accumulate metal(loid)s in high concentrations, metal(loid)s are taken up, transported, and concentrated in the aboveground biomass of plants which can then be harvested relatively easily and removed from the site (Kumar, Dushenkov, Motto, & Raskin, 1995; Salt, Smith, & Raskin, 1998; McGrath & Zhao, 2003).

Since the term hyperaccumulator was first defined by Brooks, Lee, Reeves, and Jaffre (1977), more than 500 plants have been identified worldwide as natural hyperaccumulators (Krämer, 2010). Apart from the molecular biology of the plant species, metal(loid) accumulation efficiency can also be influenced by soil factors such as pH, soil organic matter (SOM), cation-exchange capacity, and calcium carbonate (Rieuwerts, Thornton, Farago, & Ashmore, 1998; Zeng et al., 2011) as well as metal(loid) elements (Sarma, 2011). Generally, in soils with high pH (e.g., on calcareous substrates), clay, and SOM, the heavy metal(loid) mobility and bioavailability are low (Rieuwerts et al., 1998; Bradl, 2004; Liu et al., 2014).

In order to avoid problems of unintended invasions by non-native plant species (Kowarik, 2010), phytoremediation should focus on native plants (Li et al., 2003; Yoon et al., 2006; Chaney et al., 2007). Current knowledge on native hyperaccumulators for phytoremediation purposes in West Africa including Ghana is not exhaustive (Aziz, 2011; Ansah, 2012; Bansah & Addo, 2016; Nkansah, 2016), although there have been many new hyperaccumulator discoveries in tropical environments (Reeves, 2003). Ghana, formerly known as Gold Coast, is famous worldwide for its rich mineral resources and in particular, gold. Gold accounts for 45.5% of the national export earnings with a peak production in 2016 of 4.1 million ounces equivalent to a revenue of USD 5.15 billion (Ghana Chamber of Mines, 2016). The long-lasting mining tradition which dates back perhaps 2500 years (Jackson, 1992) has left many areas in Ghana with extreme heavy metal(loid) pollution, where only specialized plants can survive (Foy, Chaney, & White, 1978; Baker, 1981). Prior investigations on gold-mine tailings in Ghana found elevated to very high concentrations of As, Cd, Hg, Pb, Co, and Zn in soil (Amasa, 1975; Amonoo-Neizer, Nyamah, & Bakiamoh, 1996; Golow & Adzei, 2002; Antwi-Agyei, Hogarh, & Foli, 2009; Bempah et al., 2013).

Spontaneous natural plant colonialization and vegetation succession on mine tailings have been reported by F. Nyame (personal communication, June 08, 2017). Consequently, we hypothesize that the metalliferous soils from gold-mine tailings have a potential to host As-, Pb-, Hg-, and Cu-tolerant and even hyperaccumulating plant species. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the soil pollution level and evaluate the hyperaccumulator potential of 25 local plant species from a former gold-mine tailings deposition site in Ghana. The information provided from this study adds to existing knowledge on the status of heavy metal(loid)s in gold-mine tailings and how to mitigate adverse effects of heavy metal(loid) pollution in the environment and on human health by means of phytoremediation and soil management. Thus, we

- (1)

investigated the concentrations of As, Pb, Hg, and Cu in plant shoots and the soil of a decommissioned tailings storage facility,

- (2)

evaluated the in situ accumulation efficiency by comparing metal(loid) concentrations in the shoot biomass with those in the present soil, and

(3) assessed those soil factors that influence heavy metal(loid) mobility to improve a strategic soil management.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Site

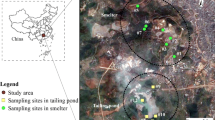

The plant and soil samples analyzed in this study were collected from a decommissioned and revegetated tailing storage site within the concession area of Damang Gold Mine in south-western Ghana, where open pit mining started in 1997 (Fig. 1). Geologically, the Damang region contains Tarkwaian System sediments and Birimian volcanic rocks: the base comprises phaneritic quartz diorite and coarse pebble-boulder conglomerate as well as sandstone, overlaid by the economically important arenaceous Banket containing quartzite and arkose associated with gold and other heavy metal(loid), and covered by Tarkwa Phylite and the uppermost Huni Sandstone (Tunks, Selley, Rogers, & Brabham, 2004; White et al., 2014). After decommissioning of the tailing site in 2003, several re-vegetation measures including soil stabilization, fertilization, pollution control, as well as visual improvement were undertaken. Currently, the former tailing site is covered with distinct vegetation types (see Fig. 1; Table 1) including an agricultural demonstration area, which is a source of income for the local community surrounding the mine. Formerly, the site was used as a deposition facility for all processed residues (in the form of slurry) generated by the mill operations. This use of the site contributed to elevated metal(loid) concentrations. In total, the tailing storage facility occupies a surface area of ca. 30 ha. The climate of the study site is tropical and characterized by a mean annual precipitation of 2030 mm and an average monthly temperature of 21–32 °C. The average altitude accounts for 115 m a.s.l. (Damang, 2011).

2.2 Plant Sampling, Sample Preparation, and Analysis

Sampling of plants and soil was carried out in June 2017 on six plots with different vegetation covers (Fig. 1). On each plot, soil and plant samples were collected in addition to a vegetation survey conducted on an area of 5 × 5 m following Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg (1974). The plant species were chosen based on the following selection criteria: (1) high abundance, (2) high vitality and productivity, and (3) literature or local knowledge on those species. Although the focus of the study was on native plant species, some non-native plant species were included due to their past establishment and high compatibility with the selection criteria. For each plant species, 10 random plant samples were taken within the area of the vegetation survey. In total, 25 plant species from 15 families were collected (Table 2). For large plants (> 30 cm in height), only leaves and twigs were sampled whereas the whole aboveground biomass was collected in the case of smaller plants.

After sampling, the aboveground plant material was transported in plastic bags to the laboratory for analysis. In the laboratory, the plant samples were washed, first under tap water followed by deionized water in order to remove all soil particles attached to the plant surfaces. The samples were air-dried followed by oven drying at 60 °C for 3 days. After drying, the samples were ground into powder using mortar and pestle. The concentrations of As, Pb, Hg, and Cu were analyzed using a 200 series atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at a wavelength of 193.7 nm, 283.3 nm, 253.7 nm, and 324.7 nm, respectively. To digest the plant samples, 0.5 g of ground plant tissue was placed into a digestion vessel, and 5 ml of HNO3 (69%) was added. Sample digestion was done by means of a microwave digestion system (Topex KJ-100, PreeKem, Shanghai, China) using a three-step procedure, involving heating at 120 °C for 2 min. On reaching 120 °C, the temperature was increased to 150 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min and then to 180 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min. Thereafter, the samples were allowed to cool to room temperature before the vessel content was filtered (Ø 0.125 mm) and quantitatively transferred into a conical plastic centrifuge tube, where it was diluted with ultra-pure water to 50 ml.

2.3 Soil Sampling and Analysis

Four randomized soil samples from the rooting zone (0–20 cm) were taken with a cylindric soil core sampler (Ø 8,9 cm) from each survey location. The soil samples, each weighing ca. 500 g, were oven dried to constant mass for 3 days at 60 °C. After drying, ca. 250 g of each sample (exact weight recorded) was ground using mortar and pestle. The sample was then sieved through a mesh with Ø 200 mm to remove rough particles. A suspension made of soil:water = 1:2.5 was prepared and stirred for 5 min. The soil pH was measured from this suspension (Bante 902, Benchtop pH/Conductivity Meter, Bante Instruments Limited, Shanghai, China). The particle size was determined by Bouyoucos Hydrometer Method (Motsara & Roy, 2008) after soil particle dispersion was done with a Calgon solution agent. Total SOM content was determined volumetrically (Walkley & Black, 1934). Total N was determined by the Kjeldahl procedure modified with the use of salicylic acid to include the mineral nitrates (Motsara & Roy, 2008).

The concentrations of heavy metal(loid)s in the soil samples were determined using a slight modification of the method used for the plant samples as described above. Soil samples were digested by first heating them at 80 °C for 3 min, followed by increasing the temperature to 120 °C at a rate of 26.67 °C/min. The samples were further heated to 150 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min before reaching the final temperature of 180 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min.

For quality control, standard soil reference material was analyzed (Moist Clay, ISE 999, Wageningen Evaluation Programs for Analytical Laboratories). Furthermore, reagent blanks and internal standards were used where appropriate.

There is no national standard established for risk assessment of heavy metal and metalloid contamination in soils in Ghana yet, and we chose the standard values set by the Finnish decree (Ministry of the Environment, 2007), which represents a good approximation of various European national standards (Toth, Hermann, Da Silva, & Montanarella, 2016) and has also internationally been applied for agricultural soils (UNEP, 2013). For each hazardous element, distinct concentration levels are set to determine soil contamination. First, the so called “threshold value” is regarded as the assessment threshold and indicates a need for further assessment of the area. The second concentration benchmark is the “guideline value” indicating ecological or health risks and a need for remediation measures.

2.4 Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF)

The bioaccumulation factor (BAF) is defined as the ratio of metal(loid) concentration in plant shoots to that in the soil of the growing site. It is a measure of the plants’ ability to take up, transport, and accumulate metal(loid)s in the shoots (McGrath & Zhao, 2003; Caille, Zhao, & McGrath, 2005; Wang, Liao, Yu, Liao, & Shu, 2009):

with BAF = the accumulation of metal(loid),

Cshoots = the metal(loid) concentration in the harvestable aboveground plant material, and

Csoil = the metal(loid) concentration in the soil.

2.5 Hyperaccumulators

The term hyperaccumulator refers to plants capable of accumulating large amounts of metal(loid)s. Per definition, plants must accumulate at least a shoot dry weight of 10 mg kg−1 Hg or 1000 mg kg−1 As, Pb, and Cu (Baker & Brooks, 1989; Lasat, 2002; McGrath & Zhao, 2003).

2.6 Statistical Analysis

To determine the concentrations of metal(loid)s in plant and soil samples, all samples of a particular species from each sampling site were respectively put together as composite (e.g., for plants, 10 sub-samples were put together to make up one sample; for soil, 4 sub-samples were put together to make up a sample for each sampling site). Each of these samples was then analyzed by two technical replicates to confirm the values obtained. Correlation analysis (Pearson correlation) between heavy metal(loid)s and soil properties was performed via correlation matrix (R-3.4.2 statistics). A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Soil Properties

The pH of soil samples from all the sites ranged from slightly acidic to alkaline (Table 3). The highest pH was found on site S5 (Table 3). The differences between the soil pH on the untreated control site S6 and pH values for the tailing sites were not significant (Kruskal-Wallis Test: Chi square = 8.0474, p = 0.15, df = 5), ranging from 0.01 to 1.32 (Table 3). The percentage of SOM ranged from 1.62 to 6.23% (Table 3). The soil cores collected on the forested sites S3 and S6 showed higher SOM contents for the surface soils than the other sites. The percentages of nitrogen (N) ranged from 0.10 to 0.45% among the sampling sites (Table 3). Site 2, an abandoned shrubland vegetation, had the highest N levels with 0.45%, followed by S3 with 0.39% (Table 3). Similarly, the percentages of sand (52–83%), silt (15–41%), and clay (2–20%) varied among the sample sites (Table 3). The soil texture of the tailing samples S1, S2, S4, and S5 was characterized by sandy loams and loam for S3, whereas the samples of the control site S6 were loamy sand according to soil textural triangle (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017). The mean clay content for S1, S2, and S6 was the least (2% each) and that for S3 was the highest (20%) (Table 3). The total amounts of elements found at the sample sites are presented in Table 3.

3.2 Total Heavy Metal(loid) Concentration in Soil

The concentrations of As, Hg, Pb, and Cu in soils measured on the five sample sites around the tailing dam, and one sample taken from an undisturbed control site are shown in Table 3. The highest As concentration of 40.25 mg kg−1 was found in tailing soils of S3 and the lowest recorded in the undisturbed soil of S6 (Table 3). The mean Hg concentrations ranged from 0.41 to 0.76 mg kg−1 whereas that of Pb ranged from 20 to 35 mg kg−1 (Table 3). Furthermore, the mean Cu concentration in the soils studied ranged from 0.08 to 15.23 mg kg−1 (Table 3). Three of the four investigated elements (As, Hg, and Pb) were above the thresholds for uncontaminated soils, while those of As also exceeded international risk thresholds.

3.3 Correlation Analysis (Heavy Metal(loid)s, Soil Properties)

The correlations (Pearson correlation) between heavy metal(loid)s as well as soil properties are presented in Table 4. There was a positive correlation among all the four elements studied, which were significant for As and Hg (p < 0.01), As and Pb (p < 0.01), As and Cu (p < 0.01), Hg and Cu (p < 0.01), as well as Pb and Cu (p < 0.05).

There was no clear trend in the correlation between soil pH and soil heavy metal(loid) concentrations (Table 4). The correlations between soil pH and As, Hg, Pb, and Cu were not significant (Table 4). No significant correlations were also found between SOM and metal(loid) contents in the soils investigated (Table 4). However, there were significant correlations between SOM and clay (p < 0.01; Table 4), as well as SOM and silt (p < 0.05; Table 4). There were positive correlations between particle size and metal(loid)s such as clay and Pb (p < 0.01) as well as clay and Cu (p < 0.05); however, sand was negatively correlated with As (p < 0.05), Hg (p < 0.01), and Cu (p < 0.05). Silt showed a positive correlation with Hg (p < 0.05) (Table 4). Soil N did not show any correlation, neither with other soil factors nor with heavy metal(loid)s (Table 4).

3.4 Heavy Metal(loid) Concentrations in Plants

A total of 25 plant species were collected in this study (Table 5). The mean metal(loid) concentration of the plant samples collected from the undisturbed soils (S6) ranged from 5.23 to 5.61 (As), 0.00095 (Hg), 0.35 to 0.45 (Pb), and 8.80 to 8.90 (Cu) (Table 5) whereas the concentration range of plants growing in tailing soils (S1–S5) were 2.18–6.83 (As), 0.00035–0.0012 (Hg), 0.15–0.40 (Pb), and 0.35–26.05 (Cu) (Table 5). Total As concentration in plant shoots ranged from 2.18 to 6.83 mg kg−1. The least concentration was detected in Brachiaria deflexa in S4 and the highest concentration measured in Leucaena leucocephala at the same site (Table 5). Mercury concentrations in most plants studied was almost non-detectable except for Alstonia boonei with a concentration of 0.00105 mg kg−1 in S2 and Stachytarpheta cayennensis growing in S1 with 0.0012 mg kg−1 (Table 5). Moreover, Pb concentrations in plants varied from 0.15 mg kg−1 in Senna siamea to 0.45 mg kg−1 in Marantochloa purpurea on site 6 (Table 5). The total Cu concentrations ranged from 0.35 mg kg−1 in Cyclosorus afer, Elaeis guineensis, and Sporobolus pyramidalis to 26.05 mg kg−1 in Aspilia africana on site 1 (Table 5). The BAF of 12 out of 25 plant species was above 1, reaching as high as 107.88 in M. purpurea on site 6 (Table 5).

Among the 25-plant species investigated for their tissue concentrations of the four heavy metal(loid)s, the highest element concentrations for each element were found in four different plant species, i.e. L. leucocephala (As), S. cayennensis (Hg), M. purpurea (Pb), and A. africana (Cu). Among these four plant species, three were shrubs and one was a non-native tree (Tables 1 and 5). Of the three shrubs two were natives and one was non-native (Tables 1 and 5). Overall, A. africana (found on site 1) consistently showed high concentration potential for As, Hg, Pb, and Cu. Additionally, M. purpurea, Costus afer, A. boonei, S. cayennensis, and Spigelia. anthelmia also showed overall high concentration potentials for all four elements. Moreover, Diplazium sammatii and S. pyramidalis showed high concentration potentials for As; Paspalum polystachyum showed high concentration potential for As and Hg; Axonopus compressus, B. deflexa, and Chromolaena odorata showed high concentration potentials for Pb, and Anthocleista nobilis and Lantana camara showed high concentration potentials for Cu (Table 5). Herbs, grasses, and ferns showed marginal concentration levels. However, no significant correlations were found for the capability to accumulate metal(loid)s with growth form or taxonomic status.

Among the four elements investigated, BAF values above 1 were only found for Cu (Table 5). A total of 12 plant species consisting of five shrubs, four trees, and three herbs from sites S1, S2, S4, and S6 had BAFs > 1 (Table 5). All the plant species collected on the sites S2 and S6 had BAF values > 1. The 12 most promising plants with BAF > 1 were M. purpurea, Co. afer, A. nobilis, L. camara, A. boonei, Mimosa pudica, Dissotis rotundifolia, A. africana, L. leucocephala, S. cayennensis, Citrus sinensis, and S. anthelmia. In comparison with the other plant species investigated, M. purpurea and Co. afer, growing on site 6 were the most efficient in accumulating all four metal(loid)s. No grasses or ferns exceeded the threshold of 1 (Table 5).

4 Discussion

4.1 Soil Properties

The pH of the undisturbed untreated forest site (S6) was not statistically different from the tailings samples, probably because of elements’ input through soil-water movement or wind erosion. Bempah et al. (2013) reported pH values of 6.12–7.85 on abandoned tailings at Obuasi gold mine in Ghana and Nejad (2010) found pH values of 7.15–7.75 in gold-mine tailings in Iran which are similar to the findings in our study. In contrast, Mkumbo, Mwegoha, and Renman (2012) reported pH values of 3.5–7.3 in a Tanzanian gold mine. The relatively high pH levels in the tailing soils of our study sites may be due to lime addition during mineral processing (Damang, 2011). Plant growth on mine substrates is supported by pH conditions between 6.0 and 7.5 (Sheoran, Sheoran, & Poonia, 2010). However, at a pH below 5.5, reduced plant growth can occur due to diminished biological activity and decreased nutrient availability and metal(loid) toxicity (Sheoran et al., 2010). Soil pH is generally acknowledged to be the main factor governing heavy metal(loid) mobility and availability to plants (Rieuwerts et al., 1998; Clemente, Walker, Roig, & Bernal, 2003). Under neutral to high pH conditions (≥ 7), heavy metal(loid)s become less mobile and available to plants, whereas at relatively low pH (ca. < 6.5), the water solubility and leaching of metal(loid)s increase (Yoon et al., 2006; Nejad, 2010; Liu et al., 2014). Thus, the pH value can be regarded as an indicator for a potential risk of heavy metal(loid) pollution. Soil pH for all samples was > 6.5 indicating a low mobility and bioavailability of heavy metal(loid)s in the soil. In general, the pH value for all survey sites on the mine tailing (6.57–7.88) was within the range for plant growth (6.0 and 7.5) and for maintaining low heavy metal(loid) mobility (> 6.5).

Soil organic matter has positive effects on plant nutrient supply and soil physico-chemical properties (Young, 1989) as well as a significant influence on metal(loid) binding and retention (Rieuwerts et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2014). Since mined soils are generally deprived of organic matter, which is critical for restoration measures and mitigation of metal(loid) pollution, the development of SOM is crucial to soil management (Mensah et al., 2015). In our study, soils from the forested sites, S3 and S6, had higher SOM contents than soils from the other sites. Moreover, SOM contents increased gradually with the age of the vegetative stands (Tables 1 and 3). Except for S3, which showed very high SOM contents at a very young stage, SOM values below 4% are considered low, medium between 4 and 10%, and high above 10% (Landon, 1991). Soils with SOM contents between 4 to 8%, such as found for the two forested sites, provide ideal conditions to support plant growth (Landon, 1991). In our study, the tailing soil at the Damang gold mine has a comparatively low SOM content, which could be improved by afforestation of the tailing. The source of the increased SOM on the forested site was probably due to litter deposition over several years, similar as reported by Mkumbo et al. (2012) for gold-mine tailings in Tanzania. Thus, forest ecosystems seem to be capable of supporting rehabilitation of SOM-deprived soils (Sheoran et al., 2010; Mensah, 2015). Interestingly, after 13 years of reforestation, the forest site S3 had a higher SOM content than the natural forest site S6. This difference in SOM content between planted (S3) and natural (S6) forests may be attributed to two factors. Firstly, the physico-chemical properties of the soil, namely the clay content (Hartati & Sudarmadji, 2016) and secondly, the vegetation type and its characteristics. F. Nyame (personal communication, June 08, 2017) reported that the stand was periodically thinned; thus, decomposed trees residuals from the last thinning left on the site, maybe the explanation for the elevated SOM content.

Nitrogen is acknowledged to be a key limiting nutrient in newly created mine substrates. Therefore, additional N fertilization may be required for the establishment and maintenance of vegetation (Sheoran et al., 2010). According to Landon (1991), N values in tropical soils are considered low below 0.2%, medium between 0.2% and 0.5%, and high above 0.5%. In this study, soils from all sites were within the range of low to medium N supply. The N levels in the tailing soils were increased by the systematic introduction of legumes and other N-fixing plant species (e.g., Pueraria phaseoloide and L. leucocephala) into the bare mine substrate (F. Nyame, personal communication, June 08, 2017). The high N content in soils of S2 is most likely the result of the previous agricultural use of the land, where supplementary artificial fertilizer was applied. Among the sites that were not artificially fertilized, the forested sites S3 showed the highest N values. The elevated N level of the forest site S3 is probably due to the elevated SOM content, which acts as a major soil reservoir for N (Sheoran et al., 2010) and the growth of N-fixing leguminous tree species such as L. leucocephala within the forest stand. Therefore, introducing N-fixing species could be an efficient measure for the fertilization of degraded mine substrates. As anticipated, the quantity of soil N, and thus the effectiveness of the fertilization, showed a strong positive correlation (R = 0.99, p < 0.05, N = 11) to the amount of SOM, which is consistent with previous research (Bear, 1977).

Soil texture is a permanent soil property and is not under influence of plants (Hartati & Sudarmadji, 2016). Thus, the restoration measures had no effect on this parameter. Generally, a loamy texture supports plant growth on tailing soils because of increased water and nutrient storage (Sheoran et al., 2010). Hence, the predominantly sandy loams of the tailing provide good basic prerequisites for plant growth. Furthermore, clay content is a significant factor for heavy metal(loid) mobility. Like SOM, clay minerals retain metal(loid) ions and thus regulate mobility and bioavailability of heavy metal(loid)s (Rieuwerts et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2014). A correlation analysis between clay content and heavy metal level showed that a positive correlation (R = 0.69, p = 0.013, N = 12) is consistent with this.

4.2 Total Heavy Metal(loid) Concentration in Soil

Arsenic was found to be the main pollutant among the four investigated elements. Although As concentrations far exceeded the recommended limit of 5 mg kg−1 for uncontaminated soil, the values were still within the intervention limit of 50 mg kg−1 for contaminated soils (Ministry of the Environment, 2007). Arsenopyrite is closely associated with Au ores and occurs naturally in the Birimian volcanic units (Smedley, 1996) which lay at the core of the Damang anticline (Tunks et al., 2004). During the processing of Au, arsenic trioxide and airborne particles are released into the environment via oxidation (Amonoo-Neizer et al., 1996; Smedley, 1996). The As contamination found in this study was notably lower than those previously reported for other industrial mining sites in Ghana. For instance, in Obuasi, Antwi-Agyei et al. (2009) reported 1711 mg kg−1 while Bempah et al. (2013) found a concentration of 1752 mg kg−1, which are among the highest in the world. This is not surprising, as only low amounts of As containing Birimian volcanics occur at the Damang deposit, while the Obuasi gold ores are rich in arsenopyrite containing sulphide minerals (Osae, Kase, & Yamamoto, 1995).

The mean Hg concentrations of the five tailing sites were higher than the threshold value (0.5 mg kg−1) for uncontaminated soil, but did not exceed the guideline value of 2 mg kg−1 (Ministry of the Environment, 2007). The measured Hg traces cannot be attributed to mining activities of the Damang gold mine, as no Hg was used in its operation since its inception. However, within the catchment communities of the mine, small scale mining activities are pervasive, where Hg after the amalgamation process is deposited (Akabzaa & Darimani, 2001; Schueler, Kuemmerle, & Schroeder, 2011). Since elevated Hg levels were found on all survey sites, including the undisturbed forest area, short to medium range atmospheric deposition of Hg via litterfall and throughfall may be the plausible cause of the Hg spikes (Ericksen et al., 2003; Li et al., 2009). Mercury deposited on the surface would be absorbed and retained by SOM. While in the Damang gold mine as well as most other industrial gold mines in Ghana, Au extraction with Hg was substituted by cyanidation, Hg continues to be utilized in artisanal gold mining (Donkor, Nartey, Bonzongo, & Adotey, 2009) leading to values as high as 2.15 mg kg−1 (Odumo, Carbonell, Angeyo, Patel, & Torrijos, 2014)..

The mean Pb concentrations for all six sites were within the recommended threshold limit of 60 mg kg−1 for uncontaminated soil (Ministry of the Environment, 2007). As fuel in Ghana is unleaded, the source of Pb pollution on the mining area may be related to galena, a natural mineral form of lead sulfide (PbS), which occurs in gold ores when sulfide concentrations of the ore are high (Matocha, Elzinga, & Sparks, 2001; Fashola, Ngole-jeme, & Babalola, 2016). Similar Pb concentrations in gold mine tailings ranging between 24 and 39 mg kg−1 were reported by Antwi-Agyei et al. (2009) in Ghana and 6 to 32 mg kg−1 by Ekwue, Gbadebo, Arowolo, and Adesodun (2012) in Nigeria.

The Cu concentrations at all sites were below the threshold value (100 mg kg−1) for uncontaminated soil (Ministry of the Environment, 2007). Copper occurs alongside gold ore bodies (Fashola et al., 2016). In gold-mine tailings in Ghana, Antwi-Agyei et al. (2009) reported Cu concentration ranging from 39.64 to 71.44 mg kg−1 while Bempah et al. (2013) found a concentration of 92.17 mg kg−1, which was higher than recorded in our study.

In general, two out of the four investigated heavy metal(loid)s (As and Hg) exceeded the thresholds for uncontaminated soil on all locations, except for the control—Site 6—where Hg was below the threshold. Moreover, As levels on all locations also exceeded the limit for phytotoxicity (20 mg kg−1) (Ross, 1994; Singh & Steinnes, 1994), whereas Hg, Pb, and Cu were constantly within the limits including 200 mg kg−1 for Pb (Ross, 1994; Singh & Steinnes, 1994), 3 mg kg−1 for Hg (Kabata-Pendias & Pendias, 1992), and > 100 mg kg−1 for Cu (Lombardi & Sebastiani, 2005). Such high levels of As are potentially toxic to plants and consequently could complicate rehabilitation measures as well as reduce growth and yield of agricultural crops. Furthermore, metal(loid)s could be accumulated in food crops and constitute a critical health risk to consumers due to the cumulative and toxic nature (McLaughlin, Parker, & Clarke, 1999). Although soil metal(loid) concentrations on all sample sites were below the guideline values set for agricultural production (Ministry of the Environment, 2007), the elevated As and Hg values continue to indicate a potential problem for food production. This is especially true, if we consider the metal(loid) accumulation potential of agricultural plants such as Citrus sinensis. In addition, Toth et al. (2016) highlight that even if crops absorb and accumulate heavy metals only in small amounts, continuous exposure to heavy metals in food can have a negative impact on human health. Thus, as a precaution measure, all cultivated crops should be thoroughly tested for their metal(loid) contents before going into production.

The total concentrations of the analyzed metals at S3, (Forest) was consistently the highest for all heavy metal(loid)s among the six survey sites and the lowest was always recorded on S6, (Forest-Control site). The metal(loid) concentrations in soil samples from the tailing sites consistently exceeded those in the undisturbed soils. It is highly probable that the elevated metal(loid) concentrations in soils from tailings dams are direct consequences of mining activities since mining was the only activity on the investigated sites. Our assumption is in line with several other studies that suggested that gold mines are a source of heavy metal(loid) contamination in the surrounding environment (Aucamp & van Schalkwyk, 2003; Antwi-Agyei et al., 2009; Bempah et al., 2013; Bempah & Ewusi, 2016; Xiao, Wang, Li, Wang, & Zhang, 2017). Furthermore, it was observed that, although element concentrations on the undisturbed control site were notably lower than on the tailing site, they were still elevated. This could be attributed to secondary element input through wind and water erosion from the surrounding tailing dams (Amonoo-Neizer et al., 1996; Antwi-Agyei et al., 2009; Bempah & Ewusi, 2016) and emphasizes the need for erosion control through effective capping with plant cover.

Among several rehabilitation techniques, the concept of reclamation forestry has demonstrated the greatest overall potential on both fertility improvement and heavy metal(loid) hazard prevention (Pulford & Watson, 2003; Mertens et al., 2007; Sheoran et al., 2010; Mensah, 2015). Rehabilitation of post-mined land with trees reduces the leaching of hazardous heavy metal(loid)s into the surrounding environment and their attendant effects on the environment and human health. Additionally, all investigated tree species showed a low metal(loid) concentration in aboveground biomass; thus, their timber can be used as an income resource without concern. Consequently, the concept of reclamation forestry could be a very cost-efficient rehabilitation measure.

4.3 Correlation Analysis (Heavy Metal(loid)s, Soil Properties)

Inter-element relationships reveal information on the sources and pathways of heavy metal(loid)s (Nejad, 2010; Liu et al., 2014). The correlation analysis (Table 4) showed that most metal(loid)s on the study sites were highly correlated (p < 0.01). This may indicate the same source of contamination and controlling factors of the metal(loid)s. Pb was the only element that showed a comparatively low linkage.

It is known that the main factors influencing the mobility of heavy metal(loid)s are pH, clay, and SOM content (Liu et al., 2014). In our study, significant correlations were found between SOM and clay, and between SOM and silt. This is not surprising, as it has been shown that loam and clay physically better protect organic material than sandy soils through their higher percentage of the total pore space (Burke et al., 1989; Hassink, Bouwman, Zwart, Bloem, & Brussaard, 1993). Findings of correlation analysis between soil metal(loid) content and particle size distribution suggest that the metal(loid) retention capacity is higher in soils with fine-grain particles such as clay minerals and humic acids (S3 and S6) due to their larger surface area in comparison with coarse-grained particles in sand (Heike B. Bradl, 2004). Soil N did not show any correlation, neither with other soil factors nor with heavy metal(loid)s.

4.4 Plant Properties and Heavy Metal(loid) Concentration

In this study, none of the plant species investigated reached the thresholds for hyperaccumulation. Nevertheless, the BAF values higher than 1 indicate a general metal accumulation potential (McGrath & Zhao, 2003; Caille et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009).

Based on the mean total BAF values of sampled plants, plants most efficiently took up Cu (BAF = 10.38), followed by As (0.17), Pb (0.01), and Hg (0.001). This pattern of metal accumulation in plants was not surprising because most of the highest concentrations were found at the sites with the lowest soil Cu contamination. Furthermore, because Cu is an essential nutrient for plants, it is not surprising that the highest bioaccumulation rates were found for this element (Yoon et al., 2006), which may also be influenced by the growth cycle-related nutrient requirements of the plants (Kabata-Pendias & Pendias, 1992). The low Pb accumulation rates were also not surprising because Pb is known to be the least bioavailable metal (Kabata-Pendias & Pendias, 1992). Pb exerts strong toxic effects on plants (Kim, Kang, Johnson-Green, & Lee, 2003) and plants may have mechanisms to avoid Pb accumulation. The elements As and Hg are non-essential for plants and have a strong negative influence on plant growth (Kabata-Pendias & Pendias, 1992).

Wang et al. (2009) argued that, the criterion of BAF > 1 does not necessarily have to be achieved by plants to qualify as hyperaccumulators. This is particularly the case for field conditions where heavy metal(loid) concentrations in soil far exceed the toxic levels for plants such that the criterion BAF > 1 would be impossible to achieve (Robinson et al., 1998; Zhao, Lombi, & McGrath, 2003). Therefore, the criterion BAF > 1 was not considered as a key parameter to identify hyperaccumulators in this study. Furthermore, the BAF is generally acknowledged to be an index for the availability/mobility of heavy metal(loid)s in soils (Bempah & Ewusi, 2016). Site specific conditions (e.g., pH value, SOM, and clay content) probably led to a significant reduction of the bioavailability of metal(loid)s leading to the low accumulation rates we recorded in plants. This assumption is in line with the correlation between metal(loid) concentrations and clay as described earlier in this study.

Baseline data on heavy metal(loid) concentrations of the soils would give a better perception of the plant assimilation abilities. However, no data prior to the revegetation was given. Furthermore, the calculation of the original heavy metal concentrations in the soil based on a simple mass balance (Alloway, 1995; Lombi & Gerzabek, 1998) was not feasible due to the unavailability of required parameters such as below ground biomass of plants and atmospheric deposition.

Hyperaccumulators of As, Hg, Pb, and Cu are of importance for phytoremediation. However, for Hg particularly, only few hyperaccumulators have been identified till date (Baker, McGrath, Reeves, & Smith, 2000; Sarma, 2011; Ali et al., 2013). The exploration of more efficient hyperaccumulators from their natural habitats is a key step for successful phytoremediation of these heavy metal(loid)s (Ali et al., 2013). Although in our study, no hyperaccumulators were identified; the climatic and metalliferous soil conditions in the area may be suitable for the evolution of hyperaccumulating plants. Earlier studies in the Obuasi gold mine in Ghana recorded BAFs as high as 12.41 and shoot concentrations of 9.7 mg−1 kg for Hg in the water fern (Ceratopteris cornuta), therefore almost reaching the hyperaccumulator threshold (Amonoo-Neizer et al., 1996). Slightly lower values were reported for Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) at the Obuasi gold mine. Thus, the phytoremediation potential of promising plant species, including M. purpurea, Co. afer, A. boonei, A. africana, L. camara, and A. nobilis needs to be further examined..

5 Conclusion

Tailing soils at the Damang gold mine are characterized by considerable amounts of As, Hg, and trace element contamination (Pb and Cu), a neutral pH, low to medium SOM content, and a soil texture of sandy loam. The amount of As in the soil exceeded the recommended threshold limits of the Finish and Swedish governments declaration, hence constituting a potential threat to the environment and human health. The amounts of Hg, Pb, and Cu were within the guideline values, and may not present a direct threat.

Among the 25 screened plant species, no hyperaccumulators for As, Hg, Pb, and Cu were identified. However, several plants showed a potential for phytoextraction for Cu. M. purpurea was most effective in taking up all four metal(loid)s, with BAF values ranging from 0.0023 to 107 (Table 5). These elevated BAF values are indicative of potential hyperaccumulator properties and the plant species (Co. afer, A. nobilis, L. camara, A. boonei, M. pudica, D. rotundifolia, A. Africana, L. leucocephala, and S. cayennensis) with high values should be further investigated.

Our findings indicate that the concept of reclamation forestry, with a high SOM enrichment capacity, has the greatest overall potential on both fertility improvement and heavy metal(loid) hazard prevention and thus can be a very cost-effective reclamation measure.

References

Akabzaa, T., & Darimani, A. (2001). Impact of mining sector investment in Ghana: a case study of the Tarkwa mining region. Washington, DC: Draft Report for SAPRIN.

Ali, H., Khan, E., & Sajad, M. A. (2013). Phytoremediation of heavy metals-concepts and applications. Chemosphere, 91(7), 869–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.075.

Alloway, B. J. (1995). Heavy metals in soils. Blackie Academic and Professional, London.

Alloway, B. J. (2013). Sources of heavy metals and metalloids in soils. In B. J. Alloway (Ed.), Heavy metals in soils (pp. 11–50). Heidelberg, Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4470-7_2.

Amasa, S. K. (1975). Arsenic pollution at Obuasi goldmine, town, and surrounding countryside. Environmental Health Perspectives, 12(December), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7512131.

Amonoo-Neizer, E. H., Nyamah, D., & Bakiamoh, S. B. (1996). Mercury and arsenic pollution in soil and biological samples around the mining town of Obuasi, Ghana. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 91(3–4), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00666270.

Ansah, K. O. (2012). Warm season turfgrasses as potential candidates to phytoremediate arsenic pollutants at Obuasi goldmine in Ghana. M.Sc. thesis: Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Antwi-Agyei, P., Hogarh, J., & Foli, G. (2009). Trace elements contamination of soils around gold mine tailings dams at Obuasi, Ghana. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 3(11), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajest.v3i11.56263.

Aucamp, P., & van Schalkwyk, A. (2003). Trace-element pollution of soils by abandoned gold-mine tailings near Potchefstroom, South Africa. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 62(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-002-0179-9.

Aziz, F. (2011). Phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soil using Chromolaena odorata and Lantana camara. MSC thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana., 1–124. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-959674.

Baker, A. J. M. (1981). Accumulators and excluders - strategies in the response of plants to heavy metals. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 3(1–4), 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904168109362867.

Baker, A. J. M., & Brooks, R. R. (1989). Terrestrial higher plants which hyperaccumulate metallic elements - a review of their distribution, ecology and phytochemistry. Biorecovery, 1(2), 81–126.

Baker, A. J. M., McGrath, S. P., Reeves, R. D., & Smith, J. A. C. (2000). Metal Hyperaccumulator plants: a review of the ecology and physiology of a biochemical resource for phytoremediation of metal polluted soils. Phytoremediation of Contaminated Soil and Water, (November 2016), 85–107.

Bansah, K. J., & Addo, W. K. (2016). Phytoremediation potential of plants grown on reclaimed spoil lands. Ghana Mining Journal, 16(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.4314/gm.v16i1.8.

Bear, F. E. (1977). Soils in relation to crop growth. Robert E Krieger.

Bempah, C. K., & Ewusi, A. (2016). Heavy metals contamination and human health risk assessment around Obuasi gold mine in Ghana. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188(5), 261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5241-3.

Bempah, C. K., Ewusi, A., Obiri-Yeboah, S., Asabere, S. B., Mensah, F., Boateng, J., & Voigt, H.-J. (2013). Distribution of arsenic and heavy metals from mine tailings dams at Obuasi municipality of Ghana. American Journal of Engineering Research, 02(05), 61–70.

Bradl, H. B. (2005). Heavy metals in the environment: origin, interaction and remediation. Elsevier Academic Press.

Bradl, H. B. (2004). Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soils constituents. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 277(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2004.04.005.

Brooks, R. R., Lee, J., Reeves, R. D., & Jaffre, T. (1977). Detection of nickeliferous rocks by analysis of herbarium specimens of indicator plants. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 7, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-6742(77)90074-7.

Burke, I. C., Yonker, C. M., Parton, W. J., Cole, C. V., Flach, K., & Schimel, D. S. (1989). Texture, climate, and cultivation effects on soil organic matter content in US grassland soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 53(3), 800–805. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1989.03615995005300030029x.

Caille, N., Zhao, F. J., & McGrath, S. P. (2005). Comparison of root absorption, translocation and tolerance of arsenic in the hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata and the nonhyperaccumulator Pteris tremula. New Phytologist, 165(3), 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01239.x.

Chaney, R. L., Angle, J. S., Broadhurst, C. L., Peters, C. A., Tappero, R. V., & Sparks, D. L. (2007). Improved understanding of hyperaccumulation yields commercial phytoextraction and phytomining technologies. Journal of Environment Quality, 36(5), 1429. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0514.

Clemente, R., Walker, D. J., Roig, A., & Bernal, M. P. (2003). Heavy metal bioavailability in a soil affected by mineral sulphides contamination following the mine spillage at aznalcóllar (Spain). Biodegradation, 14(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024288505979.

Dadea, C., Russo, A., Tagliavini, M., Mimmo, T., & Zerbe, S. (2017). Tree species as tools for biomonitoring and phytoremediation in urban environments: a review with special regard to heavy metals. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 43(434), 155–167.

Damang. (2011). Damang gold mine technical short form report. South Africa: Johannesburg.

Donkor, A. K., Nartey, V. K. V., Bonzongo, J. C. J., & Adotey, D. K. (2009). Artisanal mining of gold with mercury in Ghana. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 9(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/wajae.v9i1.45666.

Ekwue, Y. A., Gbadebo, A. M., Arowolo, T. A., & Adesodun, J. K. (2012). Assessment of metal contamination in soil and plants from abandoned secondary and primary goldmines in Osun State , Nigeria. Journal of Soil Science and Environmental Management, 3(11), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.5897/JSSEM11.116.

Eraknumen, A., & Agbontalor, A. (2007). Phytoremediation : an environmentally sound technology for pollution prevention, control and remediation in developing countries. Educational Research and Review, 2(July), 151–156.

Ericksen, J. A., Gustin, M. S., Schorran, D. E., Johnson, D. W., Lindberg, S. E., & Coleman, J. S. (2003). Accumulation of atmospheric mercury in forest foliage. Atmospheric Environment, 37(12), 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(03)00008-6.

Fashola, M., Ngole-jeme, V., & Babalola, O. (2016). Heavy metal pollution from gold mines : environmental effects and bacterial strategies for resistance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(12), 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111047.

Foy, C., Chaney, R., & White, M. (1978). The physiology of metal toxicity in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 29(1), 511–566. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.29.060178.002455.

Ghana Chamber of Mines. (2016). Performance of the Mining Industry in 2016.

Golow, A., & Adzei, E. (2002). Zinc in the surface soil and cassava crop in the vicinity of an alluvial goldmine at Dunkwa-on-Offin, Ghana. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 69(5), 638–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-002-0108-4.

Hartati, W., & Sudarmadji, T. (2016). Relationship between soil texture and soil organic matter content on mined-out lands in Berau, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Nusantara Bioscience, 8(1), 83–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.13057/nusbiosci/n080115

Hassink, J., Bouwman, L. A., Zwart, K. B., Bloem, J., & Brussaard, L. (1993). Relationships between soil texture, physical protection of organic matter, soil biota, and c and n mineralization in grassland soils. Geoderma, 57(1–2), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7061(93)90150-J.

Jackson, R. (1992). New mines for old gold: Ghana’s changing mining industry. Geographical Association, 77(2), 175–178.

Kabata-Pendias, A., & Pendias, H. (1992). Trace elements in soils and plants. CRC Press.

Kim, I. S., Kang, K. H., Johnson-Green, P., & Lee, E. J. (2003). Investigation of heavy metal accumulation in Polygonum thunbergii for phytoextraction. Environmental Pollution, 126(2), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(03)00190-8.

Kowarik, I. (2010). Biologische Invasionen: Neophyten und Neozoen in Mitteleuropa. Ulmer.

Krämer, U. (2010). Metal hyperaccumulation in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 61(1), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112156.

Kumar, P. B. A. N., Dushenkov, V., Motto, H., & Raskin, I. (1995). Phytoextraction: the use of plants to remove heavy metals from soils. Environmental Science & Technology, 29(5), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.1021/es00005a014.

Landon, J. R. (1991). Booker tropical soil manual : a handbook for soil survey and agricultural land evaluation in the tropics and subtropics. Longman Scientific & Technical.

Lasat, M. L. (2002). Phytoextraction of toxic metals: a review of biological mechanisms. Journal of Environmental Quality, 31(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2002.1090.

Li, P., Feng, X., Qiu, G., Shang, L., Wang, S., & Meng, B. (2009). Atmospheric mercury emission from artisanal mercury mining in Guizhou Province, southwestern China. Atmospheric Environment, 43(14), 2247–2251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.01.050.

Li, Y.-M., Chaney, R., Brewer, E., Roseberg, R., Angle, J. S., Baker, A., et al. (2003). Development of a technology for commercial phytoextraction of nickel: economic and technical considerations. Plant and Soil, 249(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022527330401.

Liu, G., Xue, W., Tao, L., Liu, X., Hou, J., Wilton, M., et al. (2014). Vertical distribution and mobility of heavy metals in agricultural soils along Jishui River affected by mining in Jiangxi Province, China. Clean - Soil, Air, Water, 42(10), 1450–1456. https://doi.org/10.1002/clen.201300668.

Lombardi, L., & Sebastiani, L. (2005). Copper toxicity in Prunus cerasifera: growth and antioxidant enzymes responses of in vitro grown plants. Plant Science, 168(3), 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.10.012.

Lombi, E., & Gerzabek, M. H. (1998). Determination of mobile heavy metal fraction in soil: results of a pot experiment with sewage sludge. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 29(17–18), 2545–2556. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103629809370133.

Matocha, C. J., Elzinga, E. J., & Sparks, D. L. (2001). Reactivity of Pb(II) at the Mn(III,IV) (oxyhydr)oxide-water interface. Environmental Science and Technology, 35(14), 2967–2972. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0012164.

McGrath, S. P., & Zhao, F. J. (2003). Phytoextraction of metals and metalloids from contaminated soils. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 14(3), 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00060-0.

McLaughlin, M. J., Parker, D. R., & Clarke, J. M. (1999). Metals and micronutrients – food safety issues. Field Crops Research, 60(1–2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4290(98)00137-3.

Mensah, A. K. (2015). Role of revegetation in restoring fertility of degraded mined soils in Ghana: a review. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 7(2), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJBC2014.0775.

Mensah, A. K., Mahiri, I. O., Owusu, O., Mireku, O. D., Wireko, I., & Kissi, E. A. (2015). Environmental impacts of mining : a study of mining communities in Ghana. Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 3(3), 81–94. Doi:https://doi.org/10.12691/aees-3-3-3.

Mertens, J., Van Nevel, L., De Schrijver, A., Piesschaert, F., Oosterbaan, A., Tack, F. M. G., & Verheyen, K. (2007). Tree species effect on the redistribution of soil metals. Environmental Pollution, 149(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.01.002.

Ministry of the Environment. (2007). Government Decree on the Assessment of Soil Contamination and Remediation Needs (214/2007, March 1, 2007).

Mkumbo, S., Mwegoha, W., & Renman, G. (2012). Assessment of the phytoremediation potential for Pb, Zn and Cu of indigenous plants growing in a gold mining area in Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2(4), 2425–2434. https://doi.org/10.6088/ijes.00202030123.

Motsara, M. R., & Roy, R. N. (2008). 24,. Fao Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin 19. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Mueller-Dombois, D., & Ellenberg, H. (1974). Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. Wiley.

Mulligan, C. N., Yong, R. N., & Gibbs, B. F. (2001). Remediation technologies for metal-contaminated soils and groundwater: an evaluation. Engineering Geology, 60(1–4), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7952(00)00101-0.

Nejad, B. (2010). Distribution of heavy metals around the Dashkasan Au Mine. International Journal of Environmental Research, 4(4), 647–654.

Nkansah, F. K. (2016). The potential of indigenous plants for use in phytoremediation of tailings dam at Chirano gold mine, Ghana. MSC thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana., 1–135.

Odumo, B., Carbonell, G., Angeyo, H., Patel, J., & Torrijos, M. (2014). Impact of gold mining associated with mercury contamination in soil, biota sediments and tailings in Kenya. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 21(21), 12426–12435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3190-3.

Osae, S., Kase, K., & Yamamoto, M. (1995). A geochemical study of the Ashanti gold deposit at Obuasi, Ghana. Okayama University Earth Science Report, 2, 81–90.

Prasad, M., & Freitas, H. (2003). Metal hyperaccumulation in plants- Boidiversity prospecting for phytoremediation technology. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 6(3), 285–321. https://doi.org/10.2225/vol6-issue3-fulltext-6.

Pulford, I. . D., & Watson, C. (2003). Phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated land by trees - a review. Environment International, 29(4), 529–540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-4120(02)00152-6.

Reeves, R. D. (2003). Tropical hyperaccumulators of metals and their potential for phytoextraction. Plant and Soil, 249(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022572517197.

Rieuwerts, J. S., Thornton, I., Farago, M. E., & Ashmore, M. R. (1998). Factors influencing metal bioavailability in soils: preliminary investigations for the development of a critical loads approach for metals. Chemical Speciation and Bioavailability, 10(2), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.3184/095422998782775835.

Robinson, B., Green, S., Mills, T., Clothier, B., Van Der Velde, M., Laplane, R., et al. (2003). Phytoremediation: using plants as biopumps to improve degraded environments. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 41(3), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR02131.

Robinson, B. H., Leblanc, M., Petit, D., Brooks, R. R., Kirkman, J. H., & Gregg, P. E. H. (1998). The potential of Thlaspi caerulescens for phytoremediation of contaminated soils. Plant and Soil, 203(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004328816645.

Ross, S. (1994). Toxic metals in soil-plant systems. Wiley.

Salt, D. E., Smith, R. D., & Raskin, I. (1998). Phytoremediation. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 49(1), 643–668. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.643.

Sarma, H. (2011). Metal hyperaccumulation in plants. A review focussing on phytoremediation technology.pdf. Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 4(2), 118–138. https://doi.org/10.3923/jest.2011.118.138.

Schueler, V., Kuemmerle, T., & Schroeder, H. (2011). Impacts of surface gold mining on land use systems in Western Ghana. Ambio, 40, 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0141-9.

Sheoran, V., Sheoran, A. S., & Poonia, P. (2010). Soil reclamation of abandoned mine land by revegetation : a review. International Journal of Soil, Sediment and Water, 3(2), 1–21 http://scholarworks.umass.edu/intljssw/vol3/iss2/13.

Singh, B. R., & Steinnes, E. (1994). Soil and water contamination by heavy metals. In: Lal R, Stewart BA editors. Soil processes and water quality. Advances in Soil Science. Lewis Publishers (pp. 233–272). Lewis.

Singh, R., Gautam, N., Mishra, A., & Gupta, R. (2011). Heavy metals and living systems: an overview. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 43(3), 246. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7613.81505.

Smedley, P. L. (1996). Arsenic in rural groundwater in Ghana. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 22(4), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-5362(96)00023-1.

Tchounwou, P. B., Yedjou, C. G., Patlolla, A. K., & Sutton, D. J. (2012). Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. EXS, 101, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4.

Toth, G., Hermann, T., Da Silva, M. R., & Montanarella, L. (2016). Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the European Union with implications for food safety. Environment International, 88, 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.017.

Tóth, G., Hermann, T., Szatmári, G., & Pásztor, L. (2016). Maps of heavy metals in the soils of the European Union and proposed priority areas for detailed assessment. Science of the Total Environment, 565, 1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.115.

Tunks, A. J., Selley, D., Rogers, J. R., & Brabham, G. (2004). Vein mineralization at the Damang Gold Mine, Ghana: Controls on mineralization. Journal of Structural Geology, 26(6–7), 1257–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2003.11.005.

UNEP. (2013). Environmental risks and challenges of anthropogenic metals flows and cy- cles. A Report of theWorking Group on the Global Metal Flows to the International Resource Panel (van der Voet, E., Salminen, R., Eckelman, M., Norgate, T., Mudd, G., Hisschier, R., (Vol. 346). doi:https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000108643.94730.21.

USDA. (2017). Soil Texture Calculator | NRCS Soils. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/survey/?cid=nrcs142p2_054167. Accessed 6 November 2017.

Walkley, A., & Black, I. A. (1934). An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and proposedmodification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Science, 37(1), 29–38.

Wang, S. L., Liao, W. B., Yu, F. Q., Liao, B., & Shu, W. S. (2009). Hyperaccumulation of lead, zinc, and cadmium in plants growing on a lead/zinc outcrop in Yunnan Province, China. Environmental Geology, 58(3), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1519-2.

White, A., Burgess, R., Charnley, N., Selby, D., Whitehouse, M., Robb, L., & Waters, D. (2014). Constraints on the timing of late-Eburnean metamorphism, gold mineralisation and regional exhumation at Damang mine, Ghana. Precambrian Research, 243, 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2013.12.024.

Wuana, R. A., & Okieimen, F. E. (2011). Heavy metals in contaminated soils: a review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecology, 2011, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/402647.

Xiao, R., Wang, S., Li, R., Wang, J. J., & Zhang, Z. (2017). Soil heavy metal contamination and health risks associated with artisanal gold mining in Tongguan, Shaanxi, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 141(March), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.03.002.

Yoon, J., Cao, X., Zhou, Q., & Ma, L. Q. (2006). Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in native plants growing on a contaminated Florida site. Science of the Total Environment, 368(2–3), 456–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.01.016.

Young, A. (1989). Agroforestry for soil conservation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-521X(91)90121-P.

Zeng, F., Ali, S., Zhang, H., Ouyang, Y., Qiu, B., Wu, F., & Zhang, G. (2011). The influence of pH and organic matter content in paddy soil on heavy metal availability and their uptake by rice plants. Environmental Pollution, 159(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.019.

Zhao, F. J., Lombi, E., & McGrath, S. P. (2003). Assessing the potential for zinc and cadmium phytoremediation with the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant and Soil, 249(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022530217289.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Francis Nyame for facilitating access to the Damang Gold Mine, Emmanuel Opoku Agyakwa of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana for his assistance in plant identification and Charles Asante of Soil Research Institute, Ghana for his assistance in the chemical analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. The research was financially supported in part by the University of Innsbruck and the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Petelka, J., Abraham, J., Bockreis, A. et al. Soil Heavy Metal(loid) Pollution and Phytoremediation Potential of Native Plants on a Former Gold Mine in Ghana. Water Air Soil Pollut 230, 267 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-019-4317-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-019-4317-4