Abstract

The rise of conservative religion in the West threatens the enduring positive contribution of religion to civil society, if conservative churches, as often assumed, indeed generate more bonding than bridging social capital. Against this background, this study explores the civic engagement of evangelicals in the Netherlands. Two research questions are addressed: (1) To what extent are Dutch evangelicals more involved in religious than non-religious volunteering as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members? and (2) Which decisive factors determine the religious and non-religious volunteering of Dutch evangelicals as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members? Results show that these orthodox Christians are more involved in religious than in non-religious volunteering. Their religious volunteering is determined by their church attendance, Bible reading and social embeddedness in their congregation, while their non-religious volunteering is impeded by their mono-religious orientation and social embeddedness in their congregation and by the volunteering of their parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In several countries, religion is identified as an important source of civic engagement. This is, for instance, the case in the USA (Jackson et al. 1995; Putnam 2000; Putnam and Campbell 2010), in Canada (Berger 2006; Perks and Haan 2011; Uslaner 2002) as well as in various European countries (Reitsma 2007; Ruiter and De Graaf 2006); and particularly so in the Netherlands where religious involvement continues to be an important source of civic engagement despite ongoing secularization (Bekkers 2004; 2013; Bekkers and Schuyt 2008; De Hart 1999; Vermeer and Scheepers 2012; Vermeer et al. 2016).

But one may wonder whether religious involvement will continue to be an important source of civic engagement in the near future. In the Netherlands, for instance, religious disaffiliation is massive and especially affects the younger generations, which in turn drives the ageing of the total population of churchgoers (De Hart and Van Houwelingen 2018: 46-51). If this trend continues, it is not unlikely that the current population of civically active churchgoers gradually dies out without being replaced by younger generations of civically minded churchgoers. In the long run, then, secularization may still pose a serious threat to the future of civil society, although currently the association between religious involvement and volunteering is still strong (Van Ingen and Dekker 2011). But the future of civil society is not only threatened by secularization. Next to the ageing population of churchgoers, there is another development within the religious landscape that gives us cause for concern; viz. the rise of strict or conservative religion.

Although secularization is the dominant trend in most West-European countries, it does not affect all churches to the same degree. In the Netherlands, several more conservative and orthodox churches, like certain Re-Reformed churches, and certain Pentecostal and evangelical congregations have remained fairly stable over time or have even experienced growth instead of decline during the past decades (Becker and De Hart 2006, 30–31; De Hart and Van Houwelingen 2018: 36–37). Furthermore, the Dutch situation is not unique in this respect. In Germany, for instance, religious disaffiliation among the mainline churches is equally massive, while the so-called free churches, like charismatic, Pentecostal and evangelical congregations or the Jehovah’s Witnesses, remained stable or even experienced growth (Pollack and Rosta 2015: 115–116). But this phenomenon of conservative church growth next to mainline decline is perhaps most notable in the USA where mainline Christian churches clearly give way to more conservative churches and non-denominational Evangelicalism is nowadays the largest expression of Protestantism in American society (cf. for instance Putnam and Campbell 2010, 100-108; Smidt 2015, 70–71; Stark 2015: 192–196).

This shift towards more strict or conservative religion may also pose a threat to civil society. For, as some scholars argue (cf. for instance Beyerlein and Hipp 2006; Musick and Wilson 2008: 90–96; Uslaner 2002; Wuthnow 1999), strict or conservative churches may especially encourage their membership to give their time freely to benefit their own religious community, while more liberal or mainline churches, in contrast, may encourage their membership to reach out beyond their own community. Or, to put this in terms of Putnam (2000: 22–23), conservative churches may especially generate bonding social capital, i.e. they foster connections and social networks among their own kind, while mainline churches are more likely to generate bridging social capital, i.e. they stimulate connections beyond their own communities. Thus, Wuthnow (1999: 343–344) argues, more conservative Christians, like evangelicals, foster strong in-group ties at the cost of secular civic participation, because evangelical churches expect more commitment from their members, offer more activities next to Sunday worship and emphasize their distinctiveness from the secular world.

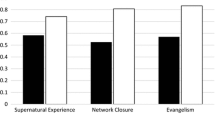

However, there is also evidence that the situation is more nuanced than this. Green (2003; cf. also Smidt 2015: 161–166), for instance, presents data showing, that although mainline Protestants indeed are most active in social programs in secular organizations, the differences with the civic engagement of evangelicals are actually quite small. Similarly, Musick and Wilson (2008: 28) mention that recently evangelicals have become more civically involved and explain this by referring to the fact that evangelicals are more inclined to see faith-based community service as a means of evangelization. Likewise, Schwadel et al. (2016) showed, that evangelicals with relatively large in-church networks are also more involved in secular civic activities and even more so than evangelicals with relatively small in-church networks. These observations could be the effect of what Coleman (1988) calls, the closure of social networks. Groups with a high degree of closure, according to Coleman, are characterized by dense social relationships and are more successful in imposing certain norms to group members. Consequently, the central religious obligation to help others in need (Musick and Wilson 2008: 88), is perhaps more successfully endorsed in strict religious groups with strong in-group ties than in more liberal religious groups. Therefore, it is not self-evident that strict and conservative churches, because they foster strong in-group ties, also discourage civic engagement. But if the latter is the case, the rise of strict and conservative religion we currently witness in various Western countries poses a serious threat to civil society.

Against this background, this study delves more deeply into the relationship between religious conservatism and civic engagement by means of a Dutch case study. More specifically, this study focuses on Dutch evangelicals and looks at their volunteering as an instance of their civic engagement. Evangelicalism, and also Dutch evangelicalism, is a clear example of a present-day, conservative religious movement. Despite internal differences and nuances, evangelicalism clearly differs from mainline Protestantism and mainline Catholicism by its focus on six fundamental convictions: ascribing absolute authority to Scripture, affirming the majesty of Jesus Christ, recognizing the work of the Holy Spirit, stressing the need for personal conversion, giving priority to evangelism and being committed to the Christian community (McGrath 1995: 55–66). Evangelicalism thus is firmly rooted in Christian orthodoxy and may be considered theologically conservative. Therefore, studying the religious and secular volunteering of Dutch evangelicals may offer additional insights into the complex relationship between religious conservatism and civic engagement and, in addition, into the future contribution of religion to (Dutch) civil society. In view of this aim, the following research questions are addressed: (1) To what extent are Dutch evangelicals more involved in religious than non-religious volunteering as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members? and (2) Which decisive factors determine the religious and non-religious volunteering of Dutch evangelicals as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members? Before we address these questions below, we first present our theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

In his book on American evangelicalism, Smith (1998) attributes the relative success of evangelicals in the USA to their ability to construct a so-called subcultural identity. Such a subcultural identity helps evangelicals to perceive themselves as a distinct religious group, which strengthens in-group social ties. Apart from this, the success of evangelicalism in the USA is also due to a degree of institutionalization, resulting in the establishment of parachurch organizations like theological seminaries, publishing houses or broadcasting companies, which facilitates subcultural persistence. Similar factors are also of importance in view of the relative success of Dutch evangelicalism, which seems less affected by the massive religious disaffiliation in the Netherlands than mainline Christianity (Becker and De Hart 206: 30–31). Boersema (2005) calls Dutch evangelicalism a conservative, reactionary movement with a distinctive religious and ethical profile and refers to the establishment of the Evangelical Broadcasting Company, today the biggest religious broadcasting company in the Netherlands, as a milestone in the history of Dutch evangelicalism. More recently, Vermeer and Scheepers (2017) showed that Dutch evangelicalism indeed differs from mainline Christianity in terms of strictness, a striving for religious homogeneity and in terms of specific organizational characteristics that evangelical congregations exhibit. Dutch evangelicals thus also display a kind of subcultural identity as a result of which they may be more oriented towards their own religious networks than to society at large. When we combine these insights with our understanding of volunteering as essentially an organized activity for either a church or religious organization (religious volunteering) or a non-religious, secular organization (non-religious volunteering) (cf. Musick and Wilson 2008: 26), our first hypothesis comes forward: Evangelicals will be more involved in religious volunteering than mainline Christians and non-church members (hypothesis 1a); they will be less involved in non-religious volunteering than mainline Christians and non-church members (hypothesis 1b); and evangelicals’ religious volunteering will exceed their non-religious volunteering to a greater degree than is the case for mainline Christians (hypothesis 1c).

But what, then, are the most important determinants for the religious volunteering of evangelicals? In view of this question, we propose three sets of possible determinants that have been linked to volunteering in previous research: specific religious factors (cf. Musick and Wilson 2008: 88–96), social network factors (cf. Musick and Wilson 2008: 267–287) and parental volunteering (cf. Musick and Wilson 2008: 227–229). Below, we consider these determinants more in detail.

To begin with, we argue that evangelicals are more involved in religious volunteering due to specific religious factors like aspects of religious socialization. On the basis of the earlier findings of Perks and Haan (2011) and Vermeer and Scheepers (2012), we assume that juvenile church attendance and having enjoyed a religious upbringing positively affect the religious, adult volunteering of evangelicals (cf. also Wilson 2012: 182). Perks and Haan found positive associations between religious involvement during school years and formal and informal, adult volunteering, while Vermeer and Scheepers showed for the Netherlands that being raised in a religious way as a youth may have a lasting effect on people’s propensity to non-religious, adult volunteering even if they lapsed in later life. Next to these socialization effects, we assume that also religious beliefs affect volunteering. To care for others in need is a core message of all major religions, which suggests that religious beliefs could motivate prosocial behaviour (Musick and Wilson 2008: 88). However, a direct link between religious beliefs and volunteering has been rarely established. Cnaan et al. (1993), for example, compared volunteers with non-volunteers and did not find any differences between these groups in terms of their intrinsic religious motivation. Still, this might be different, we propose, for a more distinctive religious group like evangelicals. For instance, the belief that the Bible contains the literal word of God and that salvation is only possible through Jesus Christ are core beliefs of evangelicals (McGrath 1995: 59–68 cf. also Smidt 2015: 92–110). Combined with a regular practice of Bible reading, such beliefs are distinctive identity markers especially in the context of secular Dutch society. Consequently, accepting the Bible as an authoritative source and viewing Jesus Christ as the only path to salvation, could make evangelicals more susceptible to the moral exhortation to help others, and especially fellow church members, in need. Thus, we assume that: Evangelicals will be more involved in religious volunteering than mainline Christians and non-church members, because they attended church as youths, were raised in a religious way by their parents, believe that the Bible contains the literal word of God, regularly read the Bible and/or have a mono-religious orientation (hypothesis 2a). However, regarding non-religious volunteering, no such differences between evangelicals, mainline Christians and non-church members are expected (hypothesis 2b).

Social network factors are powerful determinants for volunteering. Also with regard to religion are collective aspects found to be more influential than individual aspects like religious beliefs or private prayer (Wilson and Musick 1997; cf. also Van Tienen et al. 2011). This effect of collective aspects of religion is explained in terms of network theory (Bekkers 2004; Ruiter and De Graaf 2006). That is to say, religion brings people together in close-knit social networks in which engagement in voluntary work is a social norm and in which people experience peer pressure to conform to this norm. An explanation which is underpinned by an often found decreasing effect of church attendance on volunteering for religious as well as non-religious organizations, once participation in religious social networks is taken into account (cf. for instance Becker and Dhingra 2001; Jackson et al. 1995; Park and Smith 2000). Now, a distinctive feature of evangelical churches is that they are characterized by strong within-group ties. These strong within-group ties not only emerge out of the aforementioned subcultural identity of evangelicals (Smith 1998), but are also the logical consequence of their conception of the Christian life as a corporate rather than an individualistic life (McGrath 1995: 78–79). Consequently, evangelicals display far higher rates of church attendance than mainline Christians and are also more involved in religious small group activities and church social activities (Smidt 2015: 103–108; cf, also Vermeer and Scheepers 2017). Furthermore, these small group activities also strengthen friendship bonds within the congregation, which may limit the propensity of evangelicals to engage in secular and non-church activities (Iannaccone 1994; Schwadel 2005). Although there is some evidence that extensive in-church social networks may also promote secular civic activities among evangelicals in the USA (Schwadel et al. 2016), with regard to the Netherlands we assume that evangelicals who are socially integrated in their congregation will be especially inclined to engage in religious volunteering. Consequently, our next hypothesis reads: Evangelicals will be more involved in religious volunteering than mainline Christians and non-church members, because they have friends who attend the same congregation and/or because they consider their fellow church group members as friends (hypothesis 3a). However, regarding non-religious volunteering, no such differences between evangelicals, mainline Christians and non-church members are expected (hypothesis 3b).

Our third set of determinants relates to parental volunteering. Research suggests a relationship between adult volunteering and the upbringing people enjoyed as an adolescent. Particularly, adolescents who are raised by parents who are voluntary workers themselves are more likely to become volunteers as adults (Bekkers 2007; Caputo 2009; Garcia-Mainar et al. 2015; Van Houwelingen et al. 2010). Bekkers (2007) explains this link by referring to direct and indirect transmission models. Parents may stimulate prosocial behaviour of their children directly, because as volunteers they serve as important models. This direct modelling effect of parental volunteering is corroborated by many studies in various societal contexts (cf. for instance Quaranta and Dotti Sani 2016). But parents may also stimulate the prosocial behaviour of their children indirectly, by introducing them into social communities in which prosocial behaviour is an important norm. In this respect, Bekkers (2007: 102) refers to the importance of religious networks. Parents who volunteer for church are also more likely to introduce their children to voluntary activities within their religious community. Furthermore, he adds, this effect will be stronger among more conservative religious groups who display the highest rates of religious volunteering in the Netherlands (cf. Bekkers and Schuyt 2008: 89–90). Against this background, we also assume that the religious volunteering of evangelicals is in part driven by the religious volunteering of their parents. Thus, our fourth hypothesis reads: Evangelicals will be more involved in religious volunteering than mainline Christians and non-church members, because they were raised by a father and/or mother who volunteered for church or a religious organization (hypothesis 4a). However, regarding non-religious volunteering, no such differences between evangelicals, mainline Christians and non-church members are expected (hypothesis 4b).

Apart from these hypotheses concerning the determinants of the religious volunteering of evangelicals, we also test a final hypothesis relating to the spillover effect from religious to non-religious volunteering. As already shown by Jackson et al. (1995), being active in a church group may also result in secular volunteering in a non-church setting. People active in church groups are more likely to get acquainted with people in secular voluntary organizations and obtain various skills that are also useful in secular settings, which may increase the likelihood that their religious volunteering spills over to secular volunteering. However, this effect is less likely to occur among evangelicals who find plenty of opportunities to volunteer within the confines of their own religious communities and whose volunteering activities are more oriented towards maintaining the social fabric of their church (Wilson and Janoski 1995; cf. also Beyerlein and Hipp 2006; Musick and Wilson 2008: 90–96). Our fifth and final hypothesis, therefore, reads: Compared to mainline Christians and non-church members, the spill over effect from religious to non-religious volunteering will be weaker for evangelicals (hypothesis 5).

Method

Sample

Our overall sample consists of 920 respondents from two different subpopulations: evangelicals and non-evangelicals. In order to acquire a substantial number of evangelical respondents, we conducted a web search into non-denominational, Protestant congregations in the Netherlands. As an instance of purposive sampling, we specifically looked for large thriving communities, serving around 1000 attendees or more in an average week, who self-identify as evangelical. In the autumn of 2014, we had identified twelve large evangelical congregations and asked their leadership if they were willing to participate in our research by distributing a link to an online questionnaire among their members and/or attendees of 18 years or older. Six congregations, comprising a Nazarene church, two Baptist churches, an evangelical church mainly visited by people of Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles and two free evangelical churches with ties to Willow Creek Netherlands located in various parts of the Netherlands, agreed to participate and distributed the link among their members and/or attendees during the period November 2014–January 2015. This resulted in a total of 584 evangelicals who filled in our online questionnaire. However, since we used a non-probabilistic sampling method (purposive sampling), we cannot tell to what extent this sample is representative for the total population of evangelicals in the Netherlands. Moreover, such information on religious affiliation is not publicly available in our country, which limits the possibility to test for representativeness. Nevertheless, a comparison of the demographic profiles of the evangelicals in our sample and those who participated in the study of Stoffels (1990), until today the only large-scale quantitative study into the beliefs and values of evangelicals conducted in the Netherlands, hardly reveals any differences and even confirms the relatively high socioeconomic status of the evangelicals in our sample in terms of education and to a lesser extent of income.1

In order to be able to compare these evangelical respondents to mainline Christians and non-church members, we also distributed the link to our online questionnaire among a representative sample of the Dutch population. This sample was drawn in 2011 in view of the ‘Religion in Dutch society 2011–2012’ survey with previous waves of data collection in 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005. In January 2015, a letter of invitation to participate in our research was sent to 918 respondents who had stated in 2011–2012 that they were willing to participate in future research. This resulted in a total of 336 respondents who filled in our online questionnaire. In view of this response rate of 36.6%, we checked to what extent this new sample is still comparable to the original sample. A comparison of general characteristics as education, marital status and income shows that this is not entirely the case. Chi-square tests reveal that our new panel contains less lower educated and more higher educated respondents, more married respondents and less singles as well as less respondents in the lower income category. Thus, we decided to include education, marital status and income as control variables next to gender and age. Besides, income and especially education are among the strongest determinants for volunteering (Musick and Wilson 2008: 119–133), which makes it all the more necessary to control for the influence of these factors in our analyses.

However, probably due to the length of our questionnaire, several respondents did not fully complete the questionnaire. These respondents especially skipped several questions in the last part of our questionnaire and, therefore, did not score on one or more variables that are central to this study. We decided not to include these respondents in our analysis and to only include those respondents with scores on all variables. As a result, our analysis includes 664 respondents: 430 evangelicals and 234 other respondents. Again we used Chi-square tests to compare this sample of 664 respondents to the overall sample of 920 respondents and found no statistical significant differences regarding such general characteristics as gender, age, education, marital status and income. This shows that the loss of respondents is random.

Measurements

Dependent Variables: Religious and Non-religious Volunteering

In this study, we follow Musick and Wilson’s (2008: 26) understanding of volunteering as essentially an organized activity. Thus, the religious volunteering of the respondents was assessed with the help of the following question: “Do you do unpaid voluntary work for a church or other religious organization?” A question respondents could answer with yes or no. In the questionnaire, this question was immediately followed by a subsequent question meant to assess the respondents’ non-religious volunteering: “Do you do unpaid voluntary work for a non-religious organization? For example, voluntary work for a hobby club, sports club, nature preservation organization, patient association et cetera.” Again the respondents could answer yes or no.

Independent Variables: Religious Affiliation

Respondents of the evangelical subpopulation were labelled evangelical if they consider themselves to be a full member of an evangelical congregation without at the same being affiliated to another non-evangelical congregation. Respondents of the non-evangelical subpopulation could state their religious identity on a list comprising eleven Christian denominations. Their answers were collapsed into four categories: mainline Christian (Catholics and members of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands), orthodox Christian (members of various Re-Reformed churches), evangelical and none. However, since the evangelical respondents are part of a carefully selected convenience sample and the non-evangelical respondents of a national probability sample, we are in danger of comparing committed, churchgoing evangelicals with nominal Christians which could invalidate our results. In order to make more meaningful comparisons, we combined religious affiliation with church attendance and constructed the following four groups of respondents: core evangelicals and core mainline Christians, i.e. evangelicals and mainline Christians who attend religious services at least once a month, nominal Christians, i.e. mainline Christians who attend religious services less than once a month, and religious nones.2 The few orthodox Christians in our sample (N = 8) were not further subdivided into core and nominal and were, like the few nominal evangelicals (N = 4) and churchgoing nones (N = 3), also not included in the explanatory analyses. Included in our analyses thus finally are 649 (664 − 15) respondents.

Independent Variables: Religious Factors

Five religious factors are included in this study: juvenile church attendance, religious socialization, Bible reading, biblical literalism and having a mono-religious orientation. The respondents’ juvenile church attendance was assessed by asking if they attended church when they were 12–15 years old. Response categories ran from (1) almost never to (4) about once a week. Religious socialization is a composite measure combining four aspects: whether the respondent was raised in a religious way; whether this upbringing was important in the family; and whether prayer and Bible reading were regular activities in their homes. The scale runs from (0) none of the aforementioned aspects apply to the respondent to (4) all aspects apply to the respondent (Cronbach’s alpha 0.87). Bible reading was assessed by asking how often the respondent currently reads the Bible. Response categories ran from (1) never to (7) several times a day. In order to assess biblical literalism, respondents were offered four statements concerning the Bible and were asked with which statement they agree most. If respondents agreed most with the statement “From cover to cover the Bible contains the infallible word of God”, they were labelled as biblical literalists (Stoffels 1990, 151). The respondents’ mono-religious orientation was measured with help of a scale comprising three items like: “Only in Christianity do people have access to true salvation” (Vermeer and Van der Ven 2004). Response categories ran from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. For each respondent, a mean score for all three items was calculated (Cronbach’s alpha 0.94).

Independent Variables: Involvement in Socio-Religious Networks

Respondents could indicate how many of their friends attend their place of worship on a scale ranging from (1) none to (5) all. In addition, respondents active in church groups could also indicate if they consider their fellow church group members as friends on a scale ranging from (1) not at all to (4) very much.

Independent Variables: Parental Volunteering

In order to assess if the respondents were raised by parents who were themselves religious volunteers, they were asked if their father/mother volunteered for a church or other religious organization when the respondents were 12–15 years old. A question respondents could answer with yes or no. By asking if their parents volunteered for a non-religious organization like a sports club, hobby club, a nature conservation organization et cetera when the respondents were 12–15 years old, we assessed the non-religious volunteering of their father/mother. Again the respondents could answer yes or no.

Control Variables

Age is 2014 minus the respondent’s year of birth. Marital status relates to married, unmarried/single, living together, widow/widower and divorced. Education concerns the highest education completed and was collapsed into three categories lower education (highest education is lower vocational school), middle education (from lower secondary school to secondary vocational school) and higher education (from O levels to PhD or doctorate). Employment status concerns the question if the respondent has a paid job or not. Income regards the gross family income and runs from (1) less than 1000 euros to (9) more than 10.000 euros.

The descriptive statistics of all variables are presented in Table 1.

Analytical Strategy

We will present our results in two steps following our twofold research question and analytical strategy. First, we compare the proportions of religious and non-religious volunteers among the four groups we distinguish using simple cross-tabulations. This enables us to test hypotheses 1a to 1c and to answer our first research question.

Next, we address our second research question and look for the most decisive determinants of the religious and non-religious volunteering of the evangelicals in our sample as a test of hypotheses 2a to 4b. These hypotheses are tested with the help of two stepwise logistic regression analyses in which religious and non-religious volunteering are the dependent variables. Each regression analysis estimates five models. In a first model, we estimate the effect of religious affiliation. This model shows to what extent the core evangelicals and the nominal and core mainline Christians in our sample are more/less involved in religious or non-religious volunteering than the religious nones (the reference category). The next three models again estimate the effect of religious affiliation, but within each model a different set of determinants is added to the equation. If these determinants have a significant effect and at the same time reduce the initial difference with the religious nones as shown in the first model, it is possible to conclude that these determinants in part explain the volunteering of evangelicals. Thus, we try to explain away the initial differences between the groups by adding variables to equation (Davis 1985, 40). In a fifth and final model, then, all three sets of determinants together with the control variables are entered into the equation to find the most decisive determinants for the religious, and non-religious, volunteering of evangelicals. The same procedure is followed in a third and final regression analysis in which we look for a possible spillover effect from religious to non-religious volunteering as a test of hypothesis 5.

Results

Involvement in Religious and Non-religious Volunteering

Tables 2 and 3 address our first research question and display the percentages of religious and non-religious volunteers among the core evangelicals, the nominal and core Christians and the non-church members or religious nones. Table 2 shows that a large majority of the core evangelicals in our sample (89%) is indeed involved in religious volunteering and also more than mainline Christians and religious nones. This is in line with hypothesis 1a although the difference between evangelicals and core mainline Christians is actually quite small (4.2 percentage points).

When it comes to non-religious volunteering, it turns out that the core evangelicals in our sample are the least active in non-religious organizations; although still more than 43% of the evangelicals also volunteer for a non-religious organization. Nevertheless, the results of Table 3 are clearly in line with hypothesis 1b.

Finally, hypothesis 1c is also confirmed, since the difference in the percentage of religious and non-religious volunteers is biggest among the evangelicals (45.7 percentage points). In contrast, with 28.2 percentage points, the difference among nominal mainline Christians is much smaller, while core mainline Christians are as active in religious as in non-religious organizations and display no difference in this respect.

Because the number of mainline Christians involved in our analysis is actually quite small, we have to be careful in drawing conclusions here. Still, two inferences seem justified. First, the evangelicals in our sample are far more involved in volunteering for a religious than non-religious organization, which could suggest that the evangelical congregations we studied indeed generate more bonding than bridging social capital. Although these evangelicals do not turn their backs to society as more than 43% also volunteers for a secular organization. Second, these figures also show that having a firm commitment to a Christian community not necessarily goes at the cost of people’s involvement in non-religious organizations, since the core mainline Christians participating in our study are as active in religious as in non-religious volunteering.

Determinants of Religious and Non-religious Volunteering

Table 4 displays the results of the stepwise logistic regression for religious volunteering. Model 1 confirms the results presented in Table 2. Compared to non-church members, core evangelicals and core and nominal mainline Christians are significantly more likely to volunteer for a religious organization. Model 2 adds various religious factors to the equation and shows that regular Bible reading significantly increases the odds of becoming a religious volunteer. This factor decreases the initial difference with the religious nones for all religious groups, but it most strongly decreases the difference between the religious nones and the core evangelicals. In line with hypotheses 2a, we thus may conclude that evangelicals are more likely to volunteer for a religious organization, because of their regular practice of Bible reading. Model 3 adds social network factors to the equation. Having friends who worship in the same congregation increases the odds of becoming a religious volunteer and again this effect is strongest for core evangelicals. As stated by hypothesis 3a, evangelicals are indeed more likely to volunteer for a religious organization, because they have friends who worship in the same congregation. On the other hand, being raised by parents who were volunteers themselves has no effect (Model 4), which means that we have to reject hypothesis 4a. Model 5 represents the full model and also adds the control variables to the equation. This model shows that next to the effect of religious affiliation other decisive determinants for the religious volunteering of evangelicals are Bible reading and considering one’s fellow church group members as friends, while well-known determinants for volunteering as such, like income or education, have no effect.3

Table 5 displays the results of the stepwise logistic regression for non-religious volunteering. Model 1 is in line with the results presented in Table 3. Compared to non-church members or religious nones, core mainline Christians are significantly more likely to volunteer for a non-religious organization, while evangelicals are significantly less likely to do so. Model 2 adds religious factors to the equation and reveals an interesting result. Having a mono-religious orientation decreases the odds of becoming a non-religious volunteer, while the addition of this specific variable simultaneously seems to decrease the negative effect of being evangelical; i.e. the parameter changes from a significant 0.427*** in Model 1 to a non-significant 0.705 in Model 2. However, what matters is that the parameter for core evangelicals in Model 2 is no longer significant, which shows that, compared to religious nones, evangelicals are less likely to volunteer for a non-religious organization because they have a mono-religious orientation. Religious differences between evangelicals and mainline Christians thus also affect their propensity to volunteer for a non-religious organization, which is not in line with hypothesis 2b. This also goes for hypothesis 3b. Having friends who worship at the same congregation decreases the odds of becoming a non-religious volunteer for all affiliations. But adding this network factor again decreases, though slightly, the initial difference between evangelicals and religious nones (Model 1), which means that evangelicals are less likely to volunteer for a non-religious organization if they have friends worshipping at their own congregation. Model 4 now also reveals certain socialization effects of parental volunteering. Having a father who volunteered for a non-religious organization and a mother who volunteered for a religious organization are positive determinants for non-religious volunteering. Nevertheless, adding these variables to the equation slightly increases the difference between evangelicals and religious nones, which means that compared to religious nones evangelicals are less likely to volunteer for a non-religious organization if they were raised by parents who were volunteers themselves. In the final model, then, the difference between evangelicals and religious nones is no longer significant due to the effects of a mono-religious orientation, of having friends worshipping in the same congregation and parental volunteering. Religious differences as well as differences regarding social networks and socialization experiences thus also matter in view of the non-religious volunteering of these religious groups, which disconfirms hypotheses 2b, 3b and 4b.4

Hypothesis 5 regarding the spillover effect from religious to non-religious volunteering is also rejected. Table 6 shows that there is a fairly strong spillover effect (Model 2), which makes the difference between core mainline Christians and religious nones no longer significant and increases the difference between core evangelicals, as well as nominal Christians, and religious nones. This suggests that the spillover effect indeed varies per religious affiliation, but when we add interaction terms to the equation there are no significant interactions (Model 3). We find no proof, therefore, that the spillover effect is weaker for evangelicals, which means that we have to reject hypothesis 5.

Discussion

In many Western countries, the religious landscape is changing dramatically. Due to massive disaffiliation, the proportion of church members as such is decreasing, while those who remain loyal to their churches are increasingly conservative and orthodox. Overall, conservative churches seem better able to retain their membership than more liberal mainstream churches. These are significant shifts in the religious landscape, which eventually may also affect the positive contribution of religious communities to civil society. For, if conservative churches, as scholars like Wuthnow (1999) and Putnam (2000) have argued, indeed generate more bonding social capital and less bridging social capital, future generations of churchgoers will be especially oriented towards their own specific communities and less towards society at large. These considerations triggered us to study the civic engagement of Dutch evangelicals; a specific group of orthodox and conservative Christians living in the context of secular Dutch society. More specifically, we addressed the following research questions: (1) To what extent are Dutch evangelicals more involved in religious than non-religious volunteering as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members? and (2) Which decisive factors determine the religious and non-religious volunteering of Dutch evangelicals as compared to mainline Christians and non-church members?

As regards the first question, the Evangelicals who participated in our study indeed are far more involved in religious volunteering than in volunteering for non-religious organizations. In this respect, these Evangelicals differ markedly from all other religious groups, and especially from the core mainline Christians (Catholics and Protestants), who also display a high level of involvement in secular volunteering. When it comes to the determinants of their religious volunteering, our second question, it turns out that these Evangelicals especially volunteer, next to the fact that they very regularly attend church, because they read the Bible on a regular basis and are involved in socio-religious networks. Moreover, together with having a mono-religious orientation this latter involvement in socio-religious networks also appears to be a negative determinant for the non-religious volunteering of these Evangelicals. Thus, it seems to be the case that the evangelical congregations we studied indeed generate more bonding than bridging social capital as their members are more oriented towards their own religious tradition and community than towards wider society. But what do these findings tell us about the association between conservative religion and civic engagement and the future of (Dutch) civil society? In view of this question, we offer two considerations.

First, our study again confirms what previous studies repeatedly revealed: religious involvement is an important determinant for religious as well as secular volunteering (cf. for instance Wilson 2012). That is to say, mainline churchgoing Christians are as active in religious organizations as they are in non-religious organizations. Seen from this perspective, the collapse of mainline churches in the Netherlands and the relative success of more conservative churches, like various evangelical congregations, thus poses a threat to the future of Dutch civil society. That is not to say that evangelicals do not volunteer for a non-religious organization. They actually do and they only slightly differ from the nominal Christians in this respect (cf. Table 3). But our results also clearly show that evangelicals are far more engaged in religious organizations than in non-religious organizations. Moreover, we even found some evidence that their lesser willingness to engage in non-religious volunteering is in part theologically motivated. That is to say, their mono-religious orientation or belief that Jesus Christ is the only path to salvation, which is one of the core beliefs of evangelicalism (McGrath 1995: 59–68), appears to be a significant negative predictor for their engagement in secular volunteering. Consequently, the recent finding of Vermeer et al. (2016), that the link between church attendance and secular volunteering is gradually weakening over time in the Netherlands, could in part be the result of the current conservative shift in the Dutch religious landscape. Seen from this perspective, then, the positive contribution of religion to civil society may be under pressure in the near future.

However, and this brings us to our second consideration, it may also be the case that especially the minority position of Dutch evangelicals is decisive here. As a religious minority group living in a secular environment, it is vital for Dutch evangelicals to maintain a distinctive identity and to remain oriented towards their own community of fellow believers and not so much to wider society. This situation is completely different, for instance, for American evangelicals who dominate the religious landscape and are as active in volunteering for religious as well as non-religious organizations (Smidt 2015: 164–165). This explanation is supported by our finding that involvement in socio-religious networks has a positive effect on the religious volunteering of our evangelical respondents, but a negative effect on their non-religious volunteering. Thus, the more socially embedded these Evangelicals are in their congregation, the more they are involved in religious volunteering and the less they are involved in secular volunteering. This finding is opposite to the finding of Schwadel et al. (2016), we already referred to in the Introduction, who showed for two American evangelical congregations that more extensive in-church social networks positively affect both the congregants’ religious and secular civic activities. However, as a minority group Dutch evangelicals are far more urged to uphold a countercultural identity than their American co-religionists are, which probably strengthens their orientation towards their own in-group at the cost of their orientation towards society at large. Furthermore, one can also argue that maintaining an evangelical congregation in secular Dutch society is probably that demanding, that Dutch evangelicals do not have extra time left to also volunteer for secular causes. If this interpretation is correct, the lesser involvement of Dutch Evangelicals in secular volunteering might also reflect a ceiling effect. Hence, if Dutch evangelicals would gradually become more mainstream in the near future, like their American co-religionists they might also become more involved in addressing societal needs. In the end, therefore, cross-national, comparative research is needed to really find out how the rise of conservative religion affects civil society in various national contexts.

To conclude, we also have to mention an important limitation of this research. Because we used a non-probabilistic sampling method, we cannot tell to what extent our subsample of evangelicals is representative for the total population of evangelicals in the Netherlands. Although, as we mentioned in the method section, we compared the demographic profile of the evangelicals in our sample with those who participated in the earlier study of Stoffels (1990) and hardly found any differences, we cannot generalize our findings to the total population of Dutch evangelicals. Until our hypotheses are tested on the basis of more extensive and representative data, the above conclusions and considerations thus remain preliminary and tentative. Unfortunately, more extensive and representative data on Dutch evangelicals are as yet not available.

Notes

-

1.

The following congregations participated in this study: ‘Maranatha Ministries’ in Amsterdam, Church of the Nazarene in Vlaardingen, Baptist Church ‘De Rank’ in Utrecht, Free Baptist Community in Groningen, Free Evangelization in Zwolle and Evangelical Church ‘De Pijler’ in Lelystad.

-

2.

This procedure also makes it possible to include church attendance in the multivariate analyses without facing the problem of multicollinearity. Given the strong association between religious affiliation and church attendance, i.e. almost all evangelicals are regular churchgoers, multicollinearity would definitely occur if we included church attendance as a separate variable.

-

3.

Also the composite effect for the categorical control variables marital status and education is not significant. For marital status, the Wald-statistic is 2.140 (p = 0.710) and for education 3.906 (p = 0.142).

-

4.

Again the composite effect for the categorical control variables marital status, Wald-statistic is 1.642 (p = 0.801), and education, Wald-statistic is 3.055 (p = 0.217), are not significant.

References

Becker, J., & De Hart, J. (2006). Godsdienstige veranderingen in Nederland. Verschuivingen in de binding met de kerken en de christelijke traditie. Den Haag: SCP.

Becker, P. E., & Dhingra, P. (2001). Religious involvement and volunteering: implications for civil society. Sociology of Religion, 62, 315–335.

Bekkers, R. (2004). Giving and volunteering in the Netherlands: Sociological and psychological perspectives. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Bekkers, R. (2007). Intergenerational transmission of volunteering. Acta Sociologica, 2, 99–114.

Bekkers, R., & Schuyt, T. (2008). And who is your neighbor? Explaining denominational differences in charitable giving and volunteering in the Netherlands. Review of Religious Research, 50, 74–96.

Berger, I. E. (2006). The influence of religion on philanthropy in Canada. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17, 115–132.

Beyerlein, K., & Hipp, J. R. (2006). From pews to participation: The effect of congregation activity and context on bridging civic engagement. Social Problems, 53, 97–117.

Boersema, P. (2005). The Evangelical movement in the netherlands. New wine in new wineskins? In E. Sengers (Ed.), The Dutch and their gods. Secularization and transformation of religion in the Netherlands since 1950, Hilversum, Verloren.

Caputo, R. K. (2009). Religious capital and intergenerational transmission of volunteering as correlates of civic engagement. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 983–1002.

Cnaan, R. A., Kasternakis, A., & Wineburg, R. J. (1993). Religious people, religious congregations, and voluntarism in human services: Is there a link? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 22, 33–51.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Davis, J. A. (1985). The logic of causal order. Series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

De Hart, J. (1999). Godsdienst, maatschappelijke participatie en sociaal kapitaal. In P. Dekker (Ed.), Vrijwilligerswerk vergeleken. Nederland in internationaal en historisch perspectief. Den Haag: SCP.

De Hart, J., & Van Houwelingen, P. (2018). Christenen in Nederland. Kerkelijke deelname en christelijke gelovigheid. Den Haag: SCP.

Garcia-Mainar, I., Servós, C., & Gil, M. (2015). Analysis of volunteering among spanish children and young people: Approximation to their determinants and parental influence. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 1360–1390.

Green, J. C. (2003). Evangelical protestants and civic engagement: An overview. In M. Cromartie (Ed.), A public faith. Evangelicals and civic engagement. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1994). Why strict churches are strong. American Journal of Sociology, 99, 1180–1211.

Jackson, E. F., Bachmeier, M. D., Wood, J. R., & Craft, E. A. (1995). Volunteering and charitable giving: Do religious and associational ties promote helping behaviour? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 24, 59–78.

McGrath, A. (1995). Evangelicalism and the Future of Christianity. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers. A social profile. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Park, J. Z., & Smith, C. (2000). “To whom much has been given…”: Religious capital and community voluntarism among churchgoing protestants. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 39, 272–286.

Perks, Th, & Haan, M. (2011). Youth religious involvement and adult community participation: Do levels of youth religious involvement matter? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40, 107–129.

Pollack, D., & Rosta, G. (2015). Religion in der Moderne. Ein internationaler Vergleich. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, R. D., & Campbell, D. E. (2010). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Quaranta, M., & Dotti Sani, G. M. (2016). The relationship between the civic engagement of parents and children: A cross-national comparison of 18 European countries. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45, 1091–1112.

Reitsma, J. (2007). Religiosity and solidarity. Dimensions and relationships disentangled and tested, Ph.D. thesis Radboud University Nijmegen.

Ruiter, S., & De Graaf, N. D. (2006). National context, religiosity, and volunteering: Results from 53 countries. American Sociological Review, 71, 191–210.

Schwadel, P. (2005). Individual, congregational, and denominational effects on church members’ civic participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 159–171.

Schwadel, P., Cheadle, J. E., Malone, S. E., & Stout, M. (2016). Social networks and civic partcipation and efficacy in Two evangelical protestants churches. Review of Religious Research, 58, 305–317.

Smidt, C. (2015). American Evangelicals Today. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Smith, C. (1998). American evangelicalism: Embattled and thriving. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stark, R. (2015). The triump of faith. Why the world is more religious than ever. Delaware: ISI Books.

Stoffels, H. (1990). Wandelen in het licht. Waarden, geloofsovertuigingen en sociale posities van Nederlandse evangelischen. Kok: Kampen.

Uslaner, E. (2002). Religion and civic engagement in Canada and the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41, 239–254.

Van Houwelingen, P., De Hart, J. and Den Ridder, J. (2010). Leren participeren: de civil society van ouder op kind. In A. van den Broek, H. M. Bronneman-Helmers and V. Veldheer (Eds.), Wisseling van de wacht: generaties in Nederland. Sociaal en cultureel rapport 2010. Den Haag, SCP.

Van Ingen, E., & Dekker, P. (2011). Changes in the determinants of volunteering: Participation and time investment between 1975 and 2005. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quaterly, 40, 682–702.

Van Tienen, M., Scheepers, P., Reitsma, J., & Schilderman, H. (2011). The role of religiosity for formal and informal volunteering in the Netherlands. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22, 365–389.

Vermeer, P., & Scheepers, P. (2012). Religious socialization and non-religious volunteering: A Dutch panel study. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23, 940–958.

Vermeer, P., & Scheepers, P. (2017). Umbrellas of conservative belief. Explaining the success of evangelical congregations in the Netherlands. Journal of Empirical Theology, 30, 1–24.

Vermeer, P., Scheepers, P., & Te Grotenhuis, M. (2016). Churches lasting sources of civic engagement? Effects of secularization and educational expansion on volunteering for non-religious organizations in the Netherlands between 1988 and 2006. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1361–1384.

Vermeer, P., & Van der Ven, J. A. (2004). Looking at the relationship between religions. An empirical study among secondary school students. Journal of Empirical Theology, 17, 36–59.

Wilson, J. (2012). Voluntarism Research: a Review Essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41, 176–212.

Wilson, J., & Janoski, Th. (1995). The Contribution of Religion to Volunteer Work. Sociology of Religion, 56, 137–152.

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). “Who cares?” Towards an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62, 694–713.

Wuthnow, R. (1999). Mobilizing civic engagement: The changing impact of religious involvement. In T. Skocpol & M. P. Fiorina (Eds.), Civic engagement in American democracy. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vermeer, P., Scheepers, P. Bonding or Bridging? Volunteering Among the Members of Six Thriving Evangelical Congregations in the Netherlands. Voluntas 30, 962–975 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00160-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00160-1