Abstract

To investigate whether a creative writing unit in upper secondary education would improve students’ creative as well as argumentative text quality and to examine whether it would change students’ writing behavior, we tested a creative writing unit based on encouraging writing in flow by using divergent thinking tasks. Four classes (Grade 10) participated in a switching replications design. Students received either creative writing instruction (CWI) or argumentative writing instruction (AWI). Key stroke logging software recorded students’ writing processes, their Creative Self-Concept (CSC) was measured, and text quality was rated holistically. Students were positive about the design of the creative writing unit and the lessons. The effects varied per panel. The first panel showed that CWI had an effect on creative text quality compared to AWI, while AWI had no effect on argumentative text quality, compared to CWI. This pattern indicates a transfer effect of creative writing instruction on argumentative text quality. The transfer effect was moderated by CSC, with larger effects for relatively high CSC-participants. The second panel did not replicate this pattern. Instead, a crossover effect was observed of CWI in panel 1 on the effect of participating in the unit on argumentative writing in panel 2, most pronounced in high CSC-participants. Students’ creative writing speed decreased in the first panel, except for students with a relatively high Creative Self-Concept, and then increased in the second panel. Our findings may guide decisions on incorporating creative writing in the curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper presents a research study which investigated an instructional unit designed to help secondary school students become more creative in writing fictional stories. For many students, writing at school and outside school differ to some extent. For example, relatively many Dutch adolescents reported writing in their free time. 49% of school students (average age 15 years, N = 487, total population: N = 985) reported occasionally writing texts of their own in their free time (Nationale Jeugdraad [National Youth Council], 2008), such as lyrics, stories, diary entries or poems. A more recent study, under 5.000 respondents aged six and over, reported that 12% of adolescents engage in creative writing activities (Landelijk Kennisinstituut Cultuureducatie en Amateurkunst [National Centre of Expertise for Cultural Education and Amateur Arts], 2017). In primary education, 42% of pupils reported writing texts in many different genres almost daily on paper, computer, or tablet (Onderwijsinspectie [Inspectorate of Education], 2021, p. 86).

While students often write creatively at home, expository and argumentative writing are the dominant genres at school. Creative writing was removed from the Dutch national exam program in curriculum revision in upper secondary education in 1998 (Stuurgroep profiel tweede fase [Steering Group Second Phase profile], 1995). Since then, poetry and fiction writing were mostly limited to primary and lower secondary education (Van Burg, 2010; Van Gelderen, 2010). Moreover, students also noticed this change. 73% of 902 former secondary education students indicated that insufficient attention was paid to creative writing (Stalpers & Stokmans, 2019).

The removal of creative writing from the national curriculum documents is in line with a more general educational policy to focus on convergence instead of divergence, on instrumental skills and functional tasks. In the Netherlands, commercial textbooks dominate teaching practices, and provide teachers with rather convergent, closed tasks. This is not only the case in the Netherlands, but also for example in the United States, where most teachers tend to use a convergent teaching approach (Beghetto, 2010, p. 450).

This lack of attention for creativity and teaching that fosters creativity in schools, contrasts sharply with the call for creativity from modern society. It is not without reason that creativity is one of the ‘twenty-first century skills’ (Ananiadou & Claro, 2009) and that the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation published a conceptual framework for creative thinking skills as preparation for a PISA test on creativity as an innovative domain test for 2021, with written expression as one of the four domains (OECD, 2019, p. 20).

Since students enjoy creative writing in their free time, the re-introduction of creative writing might help increase their motivation for writing and thereby their writing performance. Compared to argumentative writing, creative writing processes are faster and more fluent as reported in a writing process study that recorded the writing processes of students in both genres (Ten Peze et al., 2021). This study concluded that writing flow, operationalized as greater writing speed, correlated positively with text quality in creative but also in argumentative texts (Ten Peze et al., 2021). From an instructional perspective, this suggests that instruction and practice in creative writing may enhance students’ writing flow during creative writing, as flow is inherent to the creative writing process. Furthermore, such an increase in writing speed (flow) may transfer to non-creative writing such as argumentative writing. In addition, instruction in creative writing might also affect creative text quality, according to a meta-analysis (Graham et al., 2012). Finally, since creative writing instruction aims at increasing writing speed, it may well have an impact on the quality of argumentative texts as well, since writing speed is also positively related to argumentative text quality (Ten Peze et al., 2021).

Therefore, we aimed to design and test a theory-based learning unit in creative writing, to improve secondary students’ divergent thinking, writing flow and text quality when writing both creative and argumentative texts. The outcomes of the study could guide decisions on whether to incorporate creative writing in the L1-curriculum and help secondary school teachers understand how to guide students’ creative writing and how argumentative and creative writing are related in writing education.

Theoretical background

Creativity in writing

In order to arrive at the theoretical background for the instructional design of our creative writing unit, we will first describe the key concepts underlying the design: creativity, the creative writing product, the creative writing process, and the creative person.

Creativity

Creativity can be defined in broad terms as ‘the ability to produce work that is both novel and appropriate’ at the same time (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999, p. 3). ‘Novel’ may vary from ‘unusual’ to ‘unique’ (Hayes, 1989). ‘Appropriate’ means that the creative product must fit the task, the intended audience, and the context. Glăveanu (2010, p. 80) pointed to a drawback to this definition, because the qualities mentioned cannot be easily attributed to everyday creativity and children’s products. It is not surprising that research has shifted from a focus on eminent creativity to various levels of creativity (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007; Kaufman & Beghetto, 2009) and that the traditional dichotomy between Big-C and little-c has given way to a more fine-grained distinction, for example in the Four-C model of creativity (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007). This model recognizes that creativity can vary from a subjective and personal form of creativity (mini-c) to objective forms of creativity that take place in daily life (little-c) to creativity at a professional level (Pro-c) and finally, eminent creativity (Big-C).

In the present study we studied a specific domain of creativity—creative writing. We focused on three of the four P’s that are traditionally distinguished in creativity research: the Product, Process, and Person (Kaufman & Glăveanu, 2019; Rhodes, 1961). The fourth P—Press—revolves around how the environment contributes to individuals’ creativity and is not included here.

The creative writing product

In this study we will focus on fictional texts, as a domain specific area of creativity. Fictional texts are creative when they are both original and appropriate (Hayes, 1989; Runco & Jaeger, 2012). As our study focuses on students’ little-c creativity, we defined creativity for students as ‘… products that fit into the situation or genre that is being practiced and at the same time are original and innovative’ (Kieft & Broekkamp, 2005, p. 1). Since writing is a relatively open task, all writing requires a certain amount of creativity. Writing a creative, fictional text however, requires extra investment in terms of creativity and originality. The writer must create a fictional world with fictional characters, must relate to story characters, and imagine how they feel, think and what choices they will make, all of which require imagination (Doyle, 1998).

The creative writing process

Roughly two general process models can be distinguished within research on creativity: stage-based models (Wallas, 1926) and dual-process models (among others, Finke et al., 1992; Mumford et al., 1991). Both Mumford et al. (1991) and Finke et al. (1992) abandoned the traditional stage-based models, and proposed more flexible, interactive models for the organization of sub-processes such as divergent thinking, problem finding, incubation, definition, synthesis, and analogy (Lubart, 2009). Generative and exploratory processes alternate continuously in the cyclical Geneplore model (Finke et al., 1992). The generative process creates ideas, which are evaluated and elaborated in the exploratory process, and the alternation of these processes transforms a general idea into a creative product.

For creative writing, as a specific domain of creativity, this alternation between generative and exploratory processes was confirmed by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) and Doyle (1998), who both interviewed professional novelists and poets. According to Csikszentmihalyi openness to ideas that emerge from the subconscious alternates with the writer’s critical evaluation of those ideas. Doyle also used a cyclical model, but with different concepts. She argued that writers shift between the ‘writingrealm’ and the ‘fictionworld’, especially while revising. The fiction world is characterized by narrative improvisation in which narrative elements arise unintentionally; creating the story takes over the writing process, which resembles the Geneplore model’s generative phases. The other world, the writingrealm, is the reflective writer’s mode, in which the author intentionally reflects on what is already written and what might happen next. The explorative processes take place in this writingrealm where the writer retreats to plan, write, reflect, and evaluate.

Two experimental studies sought to define the function of the generative and exploratory processes during the creative writing process in terms of resulting text quality (Fürst et al., 2017; Lubart, 1994, in Lubart, 2001), and thus included the time dimension. Lubart (1994, in Lubart, 2001) showed that early evaluating of the generated content, in the first third of the process, correlated with more creative texts. But this effect was not replicated by Fürst et al. (2017).

For the instructional design in this study, we relied on the studies by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) and Doyle (1998) and have chosen to apply Finke et al.’s (1992) dual-process model and focus on both generative and exploratory processes.

The creative person

Beghetto and Karwowski argued that a key question is whether creative self-beliefs predict creative performance (2017, p. 4). They distinguished three key self-beliefs: creative self-efficacy (CSE), creative metacognition (CMC), and creative self-concept (CSC). Creative self-efficacy is a person’s confidence to perform a task creatively while taking task constraints into account (e.g.: ‘I am able to write a creative poem for peers’). Creative metacognition is ‘a combination of beliefs based on one’s creative self-knowledge (…) and contextual knowledge (…)’ (p. 7). Creative Self-Concept is ‘a general cognitive and affective judgment of one’s creative ability’ (p. 8). These three beliefs partly overlap. CSE and CSC differ in that CSC beliefs are more general but can still be domain specific (e.g., I am a creative writer), while CSE beliefs reflect a person’s confidence to perform a specific task creatively (e.g., I can write a creative ten-line poem that does not rhyme). Furthermore, Beghetto and Karwowski emphasized that CSE and CMC are usually more cognitively oriented while CSC combines affective and cognitive components.

Despite the body of research into creative self-beliefs’ effect on performance, results remain undefined. Beghetto and Karwowski attribute this to a lack of clear definitions of creative self-beliefs and the way they are measured. Pretzl and Nelson (2017) impute the weak relationship to domain-specificity, like creativity itself. So, measuring overall creative ability might not correspond to the actual ratings in the domain at stake, like writing or mathematics.

However, the domain specificity versus generality debate has not been resolved yet. A recent study among students, suggests that the distinction between specific domains is not relevant in educational practice in which little-c creativity plays a role (Qian et al., 2019). If creativity at the little-c level is indeed primarily general, that would also explain why Pretz and Nelson (2017) could not demonstrate a correspondence between domain-specific self-perceptions and performance on a domain-specific creativity task.

We chose to focus on Creative Self-Concept in this current study for two reasons. First, in a previous study, we observed a relationship between Creative Self-Concept (CSC) and performance. Self-Concept scores correlated positively with text quality (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Second, an affective attitude to writing (‘Writing is fun’), correlated positively with text quality both directly and indirectly via writing speed (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Furthermore, the questionnaire used to measure CSC was specially developed for secondary school students in the Netherlands (Stubbé et al., 2015) and had proven to be reliable in previous research (Ten Peze et al., 2021).

Theoretical framework for creative writing instruction

Creativity has been studied relatively infrequently in psychology (Sternberg, 2009, p. 15), but creative writing has been studied even less (Fürst et al., 2017). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for elementary education by Graham et al. (2012) included only four intervention studies (Fortner, 1986; Jampole et al., 1991, 1994; Stoddard, 1982) in which creative text quality improved if students received instruction in creativity or learned how to form visual images. The average weighted effect size was nearly large: 0.70. All four studies involved young children (Grades 3–6), with a specific background: three studies concerned high-achieving students, and one involved struggling writers.

Graham et al. (2012) emphasized that control conditions varied in all four studies and that it was unclear whether students learned how to apply mental imagery or creativity in their writing. Furthermore, because these studies focused on primary education and were rather poor in quality, generalization of their findings to secondary education in terms of instructional design principles must be done with caution.

Although there is no overview of effective design principles for creative writing in secondary education, various scholars have formulated recommendations for creative-supportive environments in schools (e.g., Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Cremin & Chappell, 2021; Davies et al., 2013; Lasky & Yoon, 2020; Schacter et al., 2006). We grouped these recommendations based on Schacter et al.’s creative teaching framework supplemented by more recent insights, to create a theoretical background for the instructional design of an experimental intervention. Schacter et al. identified five areas that increase the likelihood of creative outcomes: 1. explicitly teach creative thinking strategies, 2. provide opportunities for choice and discovery, 3. encourage intrinsic motivation, 4. establish a learning environment conducive to creativity, and 5. provide opportunities for imagination and fantasy (p. 48). We will describe each of the five areas and some of the related creative teaching behaviors Schacter et al. advised below.

Explicitly teach creative thinking strategies

Schacter et al. (2006) stipulated that teachers can foster students’ creative thinking by explicitly teaching creative thinking strategies. To do so, they must provide students with learning activities that facilitate generating multiple ideas and teach students creative thinking strategies. More specifically, we propose that these activities should stimulate one or more of Guilford’s (1950) four components of divergent thinking: fluency (produce many ideas), originality (produce unusual/novel ideas), flexibility (produce various ideas to solve a problem) and elaboration (think through the details of an idea). Although Schacter et al. do not describe in detail what they mean by explicitly, it seems justified to assume that it is not sufficient to set tasks to perform (meta)cognitive thinking strategies, but that teachers must explicitly explain what these strategies are and how and under which conditions students can apply them. This is especially important because research has shown that students lack metacognitive knowledge about creativity (Pretz & Nelson, 2017).

More recent studies emphasized the importance of divergent thinking in the classroom. Cremin and Chappell (2021) analyzed 35 papers on effective creative pedagogies in a systematic review. 22 studies mentioned idea generation and exploration as key learning contents of teaching creativity (p. 311). Generative activities must be domain specific and focus on the task that students will ultimately perform; teaching divergent thinking in itself is not sufficient (Baer, 1996, 2013). In line with this, Lasky and Yoon (2020) proposed a theoretical framework to foster small ‘c’ creativity in the classroom and stated that teachers should ‘support divergent thinking that is grounded in the lesson’s activities or concepts’ (p. 2). Baer (1996) showed that creativity training which focused on divergent thinking in poetry writing led to better poems, but not to better stories, and Baer (2013) suggested that the content of the divergent thinking training should be aligned to the creative task (p. 178). Thus, it seems necessary not only to teach creative thinking strategies explicitly, but also appropriate strategies for the task at hand, in our study, to draft a fictional narrative story.

Provide opportunities for choice and discovery

Students must have a choice when required to create an original artefact in response to a problem (Lasky & Yoon, 2020; Schacter et al., 2006). In addition, ‘…students have to discover the answer by examining various models and ideas’ (Schacter et al., 2006, p. 56, italics added by authors). Choice and discovery require open target tasks with multiple possible responses, and multiple stimuli like models and examples that enable students to discover through compare and contrast activities what works best for them.

On the other hand, Davies et al.'s (2013, p. 85) systematic review on creative learning environments in education, indicated that structure and freedom must be balanced. Students’ creativity is stimulated when they receive control over their learning, but the learning environment must also be made a safe space by providing structure and support so that students dare to take risks and think creatively and critically.

Therefore, a lesson series that seeks to promote creative writing must provide an optimal balance between choice and structure and support, for instance by demonstrating different possible approaches.

Encourage intrinsic motivation

To promote intrinsic motivation among students, the task must be relevant for them, and task motivation should not depend on external cues such as grades and rewards (Amabile, 1996; Schacter et al.,, 2006). Therefore, teachers must emphasize that the creative process is worthwhile and ‘… recognizes, values, and reinforces creative thinking and creative processes’, and rewards both the product and the process (Schacter et al., 2006, p. 56).

Establish a learning environment conducive to creativity

Cremin and Chappell stressed the importance of risk-taking by students (2021, p. 316), which requires a safe and supportive environment, that provides students with a sense of independence and responsibility for their own learning (Schacter et al., 2006, p. 57). The classroom climate should challenge students to explore, ask questions, inquire, take risks, and permit failure (Schachter et al., 2006, see also Davies et al., 2013). Teachers must encourage original and unusual ideas (Schacter et al., 2006), be tolerant of and open to ideas and not steer students towards ‘the correct answer’ (Lasky & Yoon, 2020; Schacter et al., 2006).

More recent studies addressed the mode of learning to support a creative environment. Collaborative learning is an important feature of a creative environment (Cremin & Chappell, 2021; Davies et al., 2013; Lasky & Yoon, 2020). Davies et al. (2013) concluded that there is convincing evidence that students’ creativity is related to their ability to collaborate with peers. Indeed, Marcos et al. (2020) reported that fifth-grade students’ creative performance was enhanced through cooperative reading and writing activities.

In conclusion, to create a stimulating creative environment, students must be challenged to think creatively and take risks during the process and work collaboratively while feeling safe and valued.

Provide opportunities for imagination and fantasy

Finally, to enhance creative teaching, teachers should provide opportunities for imagination and fantasy and explain ‘how imagination and fantasy can lead to changing existing ideas into original creations’ (Schacter et al., 2006, p. 57). Such explanations refer to metacognitive instruction which has been proven to be effective in visual arts education (Van de Kamp et al., 2015). Thus, teachers must stimulate students to use their imagination and, ideally, apply this to real-world situations and problems (Schacter et al., 2006, p. 57). Davies et al. (2013) found that task authenticity is a crucial factor to stimulate students’ creativity. Tasks should also be novel and exciting (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Davies et al., 2013). So, effective creative writing lessons must provide metacognitive instruction and the opportunity for applying imagination and fantasy by using real and authentic tasks rather than ‘school-based’ assignments.

Based on the findings described above, we decided to develop a creative writing unit for this study, based on the principle of the dual-process model (Finke et al., 1992), using Schacter et al.’s Creative Teaching Framework as a starting point for the design principles and the lessons’ conditions. We chose to focus on a domain-specific component of creativity: secondary school students’ fictional short stories. We consider these stories as a form of little-c creativity and the creative writing process as a cyclical process in which the writer alternates generative processes in the fiction world with explorative processes in the writingrealm. Furthermore, we will focus on the product (in terms of text quality), the process (in terms of writing speed) and the creative person (in the form of Creative Self-Concept).

Research questions

The present study aimed to assess the effect of a creative writing unit on writing speed and text quality. Therefore, guided by a theoretical framework based on earlier research, we designed a unit that focusses on enhancing divergent thinking to stimulate writing flow. We expected that a unit which stimulated students’ writing flow would improve their writing performance, in terms of Text Quality and Writing Speed in creative writing tasks (Ten Peze et al., 2021). As writing speed is also positively related to text quality in argumentative writing, we will explore the transfer effects from creative writing instruction to writing speed and text quality in argumentative writing tasks. Furthermore, we explored whether these effects were independent of creativity, so that all students would benefit from the experimental unit, irrespective of their Creative Self-Concept.

Based on the above, our research questions were:

-

1.

To what extent does participation in a creative writing unit result in higher Writing Speed and higher creative Text Quality, compared to participation in an argumentative writing unit?

-

2.

Do effects on creative text writing transfer to Text Quality and Writing Speed in argumentative writing?

-

3.

Do possible effects hold for all students, irrespective of their Creative Self-Concept?

Methods

Research design and procedures

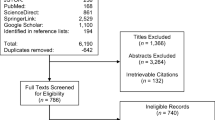

To answer the research questions, we set up a switching replications design (Shadish et al., 2002, pp. 146–147; see also Rogiers, et al., 2021; Van Ockenburg, et al., 2021) with three measurement occasions: pre- (T1), mid- (T2) and posttest (T3) and contrasting conditions (creative vs argumentative writing). Half of the participants first received creative writing instruction (CWI) and then switched to argumentative writing instruction (AWI); the other half followed the units in the opposite order (see Fig. 1). During the measurements students wrote a creative as well as an argumentative text. The resulting design is a quasi-experimental design with two panels and the advantage of a replication in the second panel and a delayed posttest at T3 for students in Panel 1. An additional advantage of this design is an ethical one, as it enables all students to participate in the instructional treatment condition and thus experience its’ potential benefits.

Two teachers, each with two classes, participated in this study. One class per teacher was randomly chosen to receive the creative instruction in the first panel, a block of six lessons, three lessons per week, in the second half of November. The second panel followed the creative instruction in late January and early February. Lessons were part of the regular schedule.

Tests were conducted at the beginning of November (T1), at the end of November (T2), and at the beginning of February (T3). Students completed two writing tasks at each measurement occasion: an argumentative and a creative writing task. Text production activities were recorded via keystroke logging (Inputlog, Leijten & Van Waes, 2013) each time. For T1 and T2, two creative (C1 & C2) and two argumentative tasks (A1 & A2) were administered in balanced order. The four possible task combinations (A1–C1, A1–C2, A2–C1, A2–C2) were pre-assigned randomly to the participants within classes, which allowed us to interpret differences in test scores between mid- and pretest as progress within conditions, while controlling for task effects. Subsequently, two new tasks, C3 and A3, were administered at T3. Contrary to the first panel, differences between T1/T2 and T3 scores cannot be interpreted in terms of progression, due to possible task effects (Schoonen, 2012; Van Ockenburg, et al., 2021).

Before T1 we collected data about students’ Creative Self-Concept using a questionnaire. After T3, we administered a questionnaire to evaluate the creative writing instruction in both panels.

Participants

Participants were 105 students of four classes from one secondary school in the Netherlands (10th grade, pre-university, 15–16 years, M = 15.15, SD = .46). Students have little experience in creative writing in this grade, at this school. The two teachers, one of whom was the first author, had 6 to 16 years’ experience teaching Dutch classes in secondary education.

The number of participants and gender distributions did not differ between conditions (respectively X2 (2) = 2, p = .37; X2 (4) = 3, p = .26) (see Table 1).

Argumentative writing unit

Our intention was not to simply compare creative writing lessons with regular lessons, such as spelling lessons, to check for maturation, but we intended to compare the creative writing unit to another writing unit. We chose argumentative writing because students are most familiar with it: they had written at least one but often two argumentative texts each school year, such as a letter to the editor of a newspaper or a letter of complaint. The argumentative writing unit we developed aimed to teach students how to write an argumentative text in which they had to convince the reader of their position on a certain topic. Practice tasks in the argumentative unit were quite similar to the test tasks that we described. The teachers chose the topics, but students could choose their own standpoint. During the lessons students wrote for example about ordering goods from AliExpress, overweight children, and a social internship for children. For one assignment they could choose between four standpoints about their own school (e.g., ‘The school day should start at 10 o’clock’, ‘The school is not allowed to sell sugary drinks’, ‘The school should teach Spanish and philosophy’ and High performing students should have the right to skip two classes of their own choice, every week’).

The two teachers collaboratively designed a unit of six 50-min lessons, based on the regular textbook used in their classes. The unit covered four main learning activities: (1) analyzing text models, (2) developing criteria for a good argumentative text, (3) practicing writing argumentative texts, and (4) sharing written texts. In lesson 1 teachers provided students with two persuasive texts, with different persuasive effects. Students had to write down suggestions for improvement and compliments on post-its. They shared their comments about the texts in groups of four and then with the whole class in a teacher-led plenary session. In lesson 2 students received direct instruction on the structure of a good argumentative text, such as taking a stance in the introduction and providing an argument in the key sentence of each paragraph, and practiced writing short introductions. The other lessons were practice lessons: students wrote persuasive texts and shared feedback with each other on post-its. So, in all lessons, students practiced writing argumentative texts and read each other’s texts in a group and gave each other feedback.

Creative writing unit: the writing lab

The Writing Lab unit’s main objective was to teach 10th grade students how to draft short creative stories (e.g., micro-stories) and how to rewrite micro-stories and story fragments into more creative versions of the original texts. There are currently no creative writing lesson series available for upper secondary schools in the Netherlands. Moreover, we are not aware of any available lesson series based on alternating divergent and convergent thinking. Therefore, we could not rely on existing materials, and designed the unit from scratch, in close collaboration with three experienced teachers from two secondary schools in the Netherlands.

The development process took about one year, in which teacher-designers met several times with the first author. The teachers piloted parts of the unit in their classes and received immediate feedback from their students. The design team also received input from an experienced creative writing teacher via an interview and a two-hour workshop in which they experienced writing in flow, using divergent thinking techniques in creative writing lessons, and in which they shared their ideas and written stories.

We formulated design principles to guide and evaluate the design process and used Schacter et al.’s framework as a theoretical basis. Therefore, we restructured the elements into a nested structure: the core of our design is the learning content, which is embedded in the learning environment, which consists of both the learning mode and the conditions required to make learning possible (see Fig. 2).

To formulate the design principles for this unit, integrating Schacter’s findings, we formulated a mapping sentence as heuristic guidance, as an adaptation of Van den Akker’s (1999) proposal:

If students must improve their creative writing, they must acquire creative thinking strategies (Content) via explicit (meta-)cognitive instruction (Mode) and expand their capacity to imagine and fantasize (Content) via well-chosen writing tasks that provide choice and discovery (Mode), in a learning environment that conduces creativity and motivation (Condition).

Next, we will justify the design decisions for each of these components and show how they relate to the design, by first providing an overview of the learning unit in six lessons (Table 2). The first lesson was a metacognitive introduction lesson, the sixth an overall application lesson. The four other lessons (2–5) each focused on an element from the story writing curriculum, such as tension building (lesson 3) and dialogues (lesson 4). Lessons two through five followed a similar pattern: alternate divergent and convergent thinking, compare and contrast, application and evaluation. In the following sections, we will explain the design rules and conditions for our design in more detail.

Design principles for effective creative writing lessons

Principle 1: Teach creative thinking strategies explicitly

The fundamental principle was the alternation between divergent and convergent thinking (Forthmann et al., 2016; Lubart, 2009), following the Geneplore model for instructional design (Finke et al., 1992). Creative thinking strategies were defined and explored in the introductory lesson, to build a knowledge base, by focusing on the nature of creativity, on the fact that creativity combines originality and appropriateness, on the difference between divergent and convergent thinking, and the different notions of creativity: from mini-c to Big-C. Students positioned themselves on the issue about learnability of creativity, observed short videos of Ken Robinson and Steve Jobs discussing creativity and shared and discussed results. They then participated in a game like activity focusing on divergent thinking.

The alternation between divergent and convergent thinking occurred in each lesson. Students practiced it in each writing assignment, so that the generative activity was contextualized (Baer, 2013; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014). The activities were explicitly indicated by icons in the students’ material and in the teacher’s slide presentation (see Appendix 1 for a sample writing assignment from lesson 2).

For the cognitive strategy instruction, we implemented a fixed series of learning activities: compare and contrast example texts or writing processes to create task representations, generate ideas through divergent thinking, select from those ideas by convergent thinking, apply their knowledge to their text, followed by evaluation. All activities were aligned to that lesson’s target task.

Compare and contrast

To design the compare and contrast activities we used Merrill’s third and fourth principle of instruction: demonstration and application. According to Merrill learning is effective ‘…when the instruction demonstrates what is to be learned’ and when the demonstration is consistent with the learning goal (p. 47, 2002). Merrill recommends the use of examples and non-examples for concepts and visualizations for processes. We implemented both options, applying comparing and contrasting as basic learning activity in observation tasks (Bandura, 1986). Observation can be an effective learning activity for complex cognitive skills like writing (Rijlaarsdam, 2005). Braaksma et al. (2010) showed that observational learning with contrasting models had a positive effect on the quality of new types of writing tasks and influenced not only the quality of the written product, but also the writing process. In our unit, students compared and contrasted strong and weak examples of two different mind maps and videos in which peer-models wrote a short creative text. They shared their findings in small groups and afterwards in a teacher-led whole class discussion.

Apply

We incorporated Merrill’s application phase in the writing unit by including a fairly extensive drafting phase during the lessons. In four lessons, students drafted their stories for as much as 20 of the 50 min of class time. In lessons 2–4, the writing tasks focused on a specific narrative element. In the final lesson, they were given the opportunity to apply everything they could have learned to their final story and drafted for almost the entire lesson.

Evaluate

Application was followed by evaluation; students always read or listened to each other’s stories in their groups, and each student was provided with either written or oral feedback on their story. The two learning activities used to stimulate evaluation of the creative texts were learner dialogues and peer feedback. Students were stimulated to participate actively in group and class discussions through open dialogues about their creative stories (Davies et al., 2013).

Since competition can be detrimental to creativity (Amabile, 1979; Kaufman & Beghetto, 2014), we chose to facilitate sharing texts in small groups. First, we made sure that students had enough time during each lesson to exchange and discuss their written texts. Second, they had to provide recommendations and compliments for each other’s stories, ask questions and discuss what makes a story creative, and how to improve a story or story fragment. Students were not trained extensively in how to provide feedback, but they were instructed to provide positive and respectful input on each other’s work. Some of the group findings were shared with the whole class, on a voluntarily basis. The feedback was either written on post-it’s by the students and attached to the text itself or discussed in the group.

Principle 2: Create opportunities for imagination and fantasy by providing choice and discovery

All writing tasks were short story writing tasks, which had to be authentic, novel, and exciting (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Davies, 2013). Authenticity was interpreted as an authentic audience: texts were written and shared with classmates, fellow writing lab members. Novel was interpreted as unusual: in each task, students had a new goal, a new narrative element to focus on. Exciting was interpreted as writing under creative constraints: solving issues in the fictionworld (Doyle, 1998) under time constraints. Students had to dive into this fictionworld through imagination: identifying a fictional character (Lesson 2), creating suspense via scene setting (Lesson 3), and continuing a dialogue between fictional characters (Lesson 4).

Regarding choice, we tried to find a balance between giving some freedom by providing options to choose from and providing sufficient structure so that students would feel safe and supported enough to think freely and explore and develop different ideas. While Schacter et al. (2006, p. 56) offered a choice between learning activities, in our design students participated in the same activities. However, they could choose between parallel open-ended creative assignments, which suited them best.

The scaffolding principle was applied to assert the required balance between structure and freedom (Lasky & Yoon, 2020), as scaffolding leads to better creative stories (Liu et al., 2014). We implemented characteristics that Van de Pol et al. (2010) considered key for scaffolding: fading and transfer of responsibility. Fading—the gradual withdrawal of scaffolding—implied that ample support was provided initially to help students invent creative ideas, but was gradually removed in later lessons, until they could work independently. As a result, students’ responsibility for task performance gradually increased.

Conditions for effective creative writing lessons

Condition 1: Encourage intrinsic motivation

To encourage students’ intrinsic motivation, we paid attention to metacognitive aspects of the creative writing process and tried to stimulate students’ affective attitude for writing. For the metacognitive aspect, we ensured that students understood that creativity is not only about inventing ideas and that it is not a matter of ‘you can or can’t’, but that creative thinking is a valuable process, which everyone can practice and improve with effort. Pretz and Nelson (2017, p. 168) showed that the belief that creativity can be nurtured, was associated with higher creative performance. Therefore, we wanted students to gain insight into their own and others creative processes, by exploring their own and others’ ideas about creativity in a group and comparing and discussing them with each other.

A previous study showed that students’ Creative Self-Concept and a positive affective writing attitude correlated positively with creative and argumentative Text Quality (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Thus, we tried to stimulate this positive affect for writing in this study as well. To do so, we incorporated assignments that were open-ended and created various possibilities for students to use their imagination (see Table 2). Furthermore, students’ serious contributions were recognized and valued during classes, and they were encouraged to think creatively (Ten Peze et al., 2021).

Finally, we tried to create tasks that were novel and exciting for students, by offering them a wide variety of different types of tasks (see Table 2) and tried to make the tasks challenging by requiring students to write their texts within a limited time span.

Condition 2: Establish a learning environment conducive to creativity

Since written texts are meant to be read, we wanted to implement a writer-reader community: all texts written in class were to be read by peers and (brief) feedback was shared. To foster creativity in the classroom, teachers should strive to promote their students’ ‘ability and willingness to evaluate their own work’ and their ‘ability to communicate their results to other people’ (Cropley (1995), p. 14). In addition, feedback is essential for the creative process (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014, p. 3). Apart from sharing in small groups, students had to be stimulated to tackle challenges (Cremin & Chappell, 2021). Therefore, the feedback provided had to be constructive and encouraging. The basic rule was that every serious contribution would be honored and appreciated, nothing was considered crazy or stupid.

The lessons were compiled in a printed student workbook, in which students wrote during every session. The workbook was accompanied by a teachers’ guide and slide shows for each session. Since we intended to examine the extent of independent transfer from creative writing to argumentative writing, the creative writing program did not address transfer to argumentative writing tasks explicitly.

Measures

To answer our research questions, we assembled and developed different instruments to collect data for four types of variables: (1) Process: Students’ Writing Speed (RQ1&2), (2) Product: Text Quality (RQ1&2), (3) Person: Creative Self-Concept (RQ3), and (4) Fidelity (see Table 3).

The creative product: text quality

During each measurement moment, students completed a creative and an argumentative writing task, which each required approximately 15 min of writing. All creative writing tasks had a similar structure, which worked well in previous research (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Students were provided with a story starter—the first lines of a story—and had to continue and finish the story themselves. All prompts were fairytales: a young princess who wakes up in the morning and does not recognize herself in the mirror (C1), a young adventurer looking for adventures (C2), and a young prince who leaves the palace every night and only returns in the early morning (C3). Fairytales were chosen to create the opportunity for a fictional world (Doyle, 1998) and stimulate imagination. No formal requirements were set, except for an expected word count and the instruction to write a compelling and original story with a suitable title.

All argumentative tasks also had a similar structure: an assignment which included a newspaper article to which students had to respond. The tasks were based on tasks from Dutch language textbooks. Students had to write a letter to the editor of a newspaper in which they responded to articles about intellectually gifted children (A1), game addiction (A2), and privacy rights for children (A3). Two tasks A1 and A2 were used in previous research (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Appendix 2 shows an example of a creative and an argumentative task and Appendix 3 shows examples of strong and weak creative and argumentative student texts with corresponding short analyses, that illustrate why we consider them to be strong and weak examples.

For creative Text Quality we adapted a rating procedure from Fürst et al. (2017) and then constructed a parallel instrument for argumentative texts. The general instruction was to keep the purpose of the text (a captivating story or a persuasive article respectively) clearly in mind while assessing the text. The instrument consisted of six items, rated on a five-point scale, from 0 = not at all to 5 = very much), representing two dimensions of creative text quality: Originality and Quality. Originality items were originality (‘This text has something special, original’) and surprise (‘This text has surprising, unexpected elements’), aesthetic (‘This text has artistic or aesthetic value’) and creativity (‘This text is creative’). Quality items were coherence (‘This text is coherent’) and quality (‘This text is well written’). Aesthetic and creativity loaded on Quality as well as Originality (p. 208). As in Furst et al.’s study, a one factor model fitted the data better than a two-factor model, for creative texts as well as for argumentative texts. In both cases the comparison between the two nested models reached p < .001).

In addition to scoring the six items, an overall Text Quality score was asked for, running from 0 to 100 (See Appendix 4 for the assessment instructions). The correlation between aspect scores and the overall Text Quality score varied from .58–80, with a mean of .69 for argumentative tasks and from .64 to .80, with a mean of .73 for creative tasks, indicating that the overall holistic scores represented the six aspects. Therefore, we decided to use the holistic scores in further analyses, as holistic scores are often used in creativity research and proved to be best choice for reasons of generalizability (Van den Bergh et al., 2012).

To increase the study’s generalizability and to keep raters’ workload manageable, many experienced teachers of Dutch language and literature (N = 30) participated in the text rating process. Each teacher rated a portion of 50–60 creative or argumentative texts. Within text types, we created overlapping rater teams of three raters per text (Van den Bergh & Eiting, 1989). Jury reliabilities for the six tasks ranged from .71 to .82.

The process: writing speed

At all three measurement occasions students wrote their text in MS Word on a computer in one of the school’s computer classrooms. Their writing behavior was recorded with a keystroke logging program: Inputlog (version 7.0.0.11; Leijten & Van Waes, 2013), which enabled us to reconstruct the entire writing process. All recordings were unobtrusive, since the program registers all activities (typing, deleting, pausing, replacing, copying) and mouse movements in the background.

Based on the focus of the intervention, a previous process study (Ten Peze et al., 2021), and an analysis of the relation between process variables and Text Quality at the pre-instruction pretest measurement, we selected one variable for Writing Speed, operationalized as the average number of strokes produced during the writing process per minute, without inserted and replaced characters. This variable is an indication of the Writing Speed for all strokes whether they were deleted or not. The scores on three intervals –beginning, middle and end—were used to check which interval is most sensitive for changes due to the intervention. We chose to focus on Writing Speed, as an operationalization for writing flow, based on an earlier process study on creative writing (Ten Peze et al., 2021), which indicated that students’ writing speed differed when writing based on creative and argumentative prompts. Furthermore, writing speed was positively related to text quality in both genres, with higher speed in creative tasks on average than in argumentative ones. Given the potential benefits of writing flow (Ten Peze et al., 2021), we aimed to increase students’ writing speed in the present course.

The creative person: learner variables

We applied a Creative Self-Concept questionnaire to measure general creative ability, designed and tested by Stubbé et al. (2015) for use in Dutch secondary education. The 44 items represent a construction matrix with seven constructs: inquisitiveness, imaginativeness, focus on output, pride in own work, dare to be different, persistence, and collaborativeness. A 7-points Likert scale was used (1 = does not apply to me, 7 = completely applies to me) to indicate students’ perception of their creative competences (Cronbach’s alpha was .92). We used the compound average score in the analyses.

Fidelity: attendance data and student workbooks

To determine whether the intervention was carried out with sufficient fidelity (O’Donnell, 2008), we tracked students’ attendance records for both conditions and took samples of students’ creative writing workbooks, 26 from each panel, to verify that they completed the assignments they were expected to do. We calculated the percentage of students present during the intervention based on the total number of classes all students attended.

All students participated in the divergent thinking assignment in the first lesson and wrote a final text during the last lesson. During lessons 2 through 5, all students wrote their assignments in their workbooks. For lessons 2, 4 and 5 we defined two assignments as crucial to the successful completion of the lesson: the divergent thinking assignment and the drafting assignment, as well as the drafting assignment in lesson 3. If there were two divergent thinking phases in a lesson, we chose the first one as the crucial assignment. Subsequently, we noted whether the crucial tasks had been completed in all the workbooks.

Appreciation of the creative writing unit

We designed a student questionnaire to check the instructional design’s implementation fidelity (O’Donnell, 2008), to test for possible differences between the two panels in this respect, and determine whether participants were positive about the design principles. It consisted of seven parts (see Table 4), with items on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Data analysis

Fidelity: attendance data and student workbooks

The percentage of students who attended all creative writing classes was remarkably high: the absentee rate was below 1% for all occasions in both conditions in panel 1 and less than 1% for the AWI-CWI Group and less than 3% for the CWI-AWI Group in panel 2. Students’ performance of the assignments during the creative writing unit was also satisfactory. Almost all students completed all divergent thinking assignments (Panel 1: 88%; Panel 2: 94%) and all writing assignments (Panel 1: 90%; Panel 2: 88%).

Appreciation of the creative writing unit

We dealt with all separate items per cluster (7) via repeated measures analysis, with items in the scale as within factor and Group (CWI-AWI vs AWI-CWI) as between subjects factor. We tested the effect of items, group, and interactions between these factors. We will focus on differences between groups, and whether scores indicate a sufficient level of perceived implementation. We would expect scores above 3 (neutral) for positive and below 3 for negative statements.

Participants in both panels were generally positive about the planned elements in the instructional design, as only two items scored below neutral (see Online Resource 1). Differences between groups were scarce. A Group effect was found for only one scale: Evaluation of Key Features of the unit. Although the mean score was sufficient in both groups, students in the Creative Writing intervention in Panel 2 scored significantly higher than the other group (Handwriting: 3.7 (SE = 0.12) vs 3.0 (SE = 0.13) and Frequent Writing: 3.4 (SE = 0.14) vs 3.0 (SE = 0.14)). No differences between groups or interactions between groups and items were observed in the other cluster.

Text quality

Mixed models were used to analyze the data, because the design included scores on three measurement occasions nested in individual students, who were nested in intact classes. We compared the fit of eight nested models, for Creative and Argumentative tasks separately, starting with a null model, in which the intercept was estimated with participants in classes as random factor. Subsequently, we added factors and interactions: Time (model 1), Condition (model 2), Interaction between Time and Condition (model 3), the effect of a learner characteristic (Creativity; centered; model 4), and the interactions between this learner variable and Time (model 5), Condition (model 6), and between Time and Condition (model 7). We tested these models for Global Text Quality scores. Note that we included the learner variable scores in these analyses as a continuous score.

To gain insight in the significant effects of Condition at the two posttest measurements (T2, T3) we reran the analysis for the best fitting model with dummy variables for the effect of Condition, the effect of Condition on Time 2, and on Time 3. While the best model contained factors that included the learner variable Creativity, we also added the effect of Creativity and the relevant interaction between the dummy variables and the learner variable as well.

Writing speed

We checked for outliers via boxplot analyses and then winsored scores that were outside reasonable ranges. For all four variables, speed total and speed in each of the three intervals, we applied the same set of nested models as for Text Quality and estimated the effects of conditions and time under the best fitting model with dummies as we did for the analysis of Text Quality, under model 3.

Results

In this section we present the outcomes of the intervention for Text Quality (Product), Writing Speed (Process) and Creative Self-Concept (CSC) (Person).

Text quality

Multilevel analyses revealed that for both Argumentative and Creative Text Quality tasks, Model 7 fitted best, which implies that the interaction between Condition and Time is affected by learners’ level of CSC. The comparison for the models for Argumentative and Creative Text Quality can be found in Online Resource 2.

Argumentative tasks

Fig. 3 (panel B) shows the scores for argumentative tasks. See Online Resource 3 for estimated average scores and standard errors. Effects were observed for Time (F(2, 697) = 7.432, p = .001; T3 > T2: p = .001; T3 > T1: p = .001) and an interaction between Time, Condition and Learner Variable on Time 3 (t(711.288) = 3.715, p < .001). These results indicate that during the first panel, the difference in conditions did not result in different Text Quality scores for Argumentative texts. But when groups switched to instruction in the other text type in panel 2, then an effect for the CWI-AWI Group on the quality of Argumentative tasks is observed, moderated by CWI-AWI Group participants’ level of creativity: the higher their level of creativity, the higher their scores on argumentative Text Quality in panel 2 (M = 6.282, se 1.691, p < .001).

Effect of conditions across time for creative (Panel A) and argumentative (Panel B) text quality. Panel A Effect of conditions across time for creative Text Quality (holistic score) for three levels of creativity (Low, Average, High); estimated under Model 7. Panel B Effect of conditions across time for argumentative Text Quality (holistic score) for three levels of creativity (Low, Average, High); estimated under Model 7

Creative tasks

No effect of Time was observed. For Condition, a positive effect was found on Time 2 for the CWI-AWI Group, thus after having been exposed to creative writing instruction (t(718.735) = 2.172, p = .003). Similar to argumentative tasks, an interaction was observed between Condition and Creativity at Time 3, in which Creativity positively influences the effect in the CWI-AWI Group on creative Text Quality (t(724.135) = 3.97, p < .001) (see Fig. 3, panel A).

The differences in slope in Panel 1 were significant. For Creative tasks the effect was 2.891 (SE = 1.330, p = .003). The positive sign implies that the CWI-AWI group outperformed the AWI-CWI group in terms of Text Quality in panel 1. For panel 2, the differences in slopes did not reach statistical significance (M = − 2.345, SE = 1.372, p = .089), but the moderator effect for this slope was significant (M = 7.017; SE = 1.767, p < .001), indicating that the effect was larger when students’ Creative Self-Concept level was higher.

Writing speed

The model comparisons for two text types, Creative and Argumentative, for the variable Writing Speed, calculated over the entire process and each of the three intervals can be found in Online Resource 4. No effects of conditions were observed in interval 2 and 3, nor in creative or argumentative tasks. Therefore, we will focus here on the entire process and on interval 1.

For both Text Types, an interaction between condition and measurement moment was observed which indicates an effect of the instruction condition in at least one of both panels (Model 3). Adding Creative Self-Concept improved the fit of the model (Model 7), indicating that the effect of instruction condition (Model 3) varied by the level of Creative Self-Concept. We ran the analyses with dummy variables to estimate the effects of all components of Model 7 for each panel (See Online Resource 5). Figures 4 and 5 show the developments of Writing Speed scores for the entire process and interval 1 respectively, for both writing text types, for the average level of creativity and one standard deviation above or below. Note however that the variable we included in the analyses is continuous; we selected three points from the distribution for presentational reasons.

Creative tasks

In panel 1, the CWI-AWI group wrote significantly slower at T1 than at T2 (b = − 4.72, SE = 0.196 (Fig. 4A). This effect cannot be attributed to one of the three process intervals. In Panel 2, however, when this group received instruction in argumentative instead of creative writing, their writing speed in creative texts increased (b = 10.73, SE = 1.99), in the first interval (b = 13.50, SE = 6.84; Fig. 5A).

Argumentative tasks

No effects were observed in panel 1, but in panel 2, the CWI-AWI group wrote faster at T3 than T2 (b = 11.33, SE = 2.00), an effect observed in interval 1 (b = 26.75, SE = 7.22) (see Fig. 4B).

Creative Self-Concept moderates the condition effect for both Text Types, in both panels: the effect of the creative writing instruction is positive for Creative texts in panel 1 (b = 5.02, SE = 2.55), but cannot be attributed to a specific process interval. In Panel 2, the effect is also positive, clearly attributable to the first interval (resp. b = 8.34, SE = 2.52 for the whole process, b = 18.97, SE = 8.65 for interval 1). This effect in the whole process is also present for argumentative texts (b = 8.84, SE = 2.65) but not in the first interval (b = 16.15, SE = 9.40, p = − .09).

Discussion

In the present study, we used a switching replication design to investigate whether a creative writing instruction unit would improve students’ creative writing in terms of writing speed and text quality (RQ1). Second, we sought to investigate whether the unit’s effect on students’ creative writing transferred to their argumentative writing speed and text quality (RQ2). Finally, we explored whether effects were independent of Creative Self-Concept (RQ3).

RQ 1: The effect of a creative writing unit on creative text quality and creative writing speed

Based on our results, we conclude that the creative writing unit was partially successful in affecting Text Quality and Writing Speed.

In panel 1, which was an experimental setting with counterbalanced pre- and posttest tasks, Creative Writing Instruction (CWI) had a general effect on Creative Text Quality. However, panel 2, with different tasks on both measurement occasions (T2, T3), did not replicate this effect (p = .09). The absence of a replication effect is unlikely to be due to differences in the instruction provided, as no differences in students’ appreciation of the CWI were found. Furthermore, fidelity of implementation did not differ between panels 1 and 2, no disruptive situations were reported in the second panel, and its timing (January–February) also does not seem to have played a role. The explanation we would like to propose is the impact of the effect in panel 1. The final measurement occasion, after panel 2, is in fact a retention measure for the experimental CWI group in panel 1. If participation in CWI does affect students’ participation in the Argumentative Writing Instruction unit (AWI) in panel 2, that might explain why the differences between the two courses are smaller in panel 2 than panel 1. However, as the tasks at T2 and T3 were not counterbalanced, we cannot interpret the differences between T2 and T3 scores as progress, which hinders the interpretation of the effect of CWI in panel 2.

Effects were also found of CWI on Writing Speed in Creative Tasks. Unexpectedly, students’ writing speed decreased in general in panel 1 but then increased in panel 2. Our intention was to stimulate writing flow, since we found in a previous study that Writing Speed was positively related to Text Quality (Ten Peze et al., 2021). Therefore, we placed a strong emphasis on writing fast in the CWI. However, the tasks written during the course were prepared using divergent and convergent thinking activities before actual text production, while the tasks written at the measurement moments were not. During the measurement moments no scaffolds were available: generating ideas and text production had to be done in the same session. An important feature of the divergent thinking exercises students performed during the lessons was to think beyond their first idea to arrive at a truly original idea. Searching for the most original idea may have taken more time at measurement moments T2 after following the CWI lessons than before (T1). Interestingly, if this explanation might be valid, one would expect the text production delay to take place in the first interval of the writing process. Most students generate their ideas primarily during that first phase (Fürst et al., 2017) followed by a more fluent and faster process, at least in interval 2. But this effect on Writing Speed is not observed in interval 1, nor in the other intervals. Instead, this may point to a more continuous alternation between generation and production as the Geneplore model proposes (Finke et al. 1992, p. 17).

Remarkably, this effect is not replicated in panel 2. Instead, the group that switched to the AWI-course, wrote their creative texts much faster at T3, an effect that took place in the first interval of the process. Whether this is a delayed effect of participating in the CWI unit in panel 1 cannot be demonstrated.

RQ 2: Transfer and carryover effects from creative writing to argumentative writing

Subsequently, we explored whether there was a transfer effect from the creative writing unit (CWI) to argumentative writing (AWI). Indeed, in panel 1 we found a pseudo transfer effect from CWI to the quality of argumentative texts and found a carryover effect from creative writing to argumentative writing in panel 2.

Transfer

Text Quality did not differ between the two groups at T1, and after instruction, no differences between the two groups were observed for Argumentative Texts, even though the AWI group participated in a course on Argumentative Writing. Thus, the CWI course students outperformed the AWI course students for Creative Texts, but the AWI students did not outperform the CWI students for Argumentative Texts. It is tempting to label this pattern as a transfer effect of CWI on Argumentative Texts. However, none of the courses improved Argumentative Text Quality. The AWI course was based on regular textbook materials, with some instructional extras, and practice tasks. Our results indicated that such a course does not result in improvement of Argumentative Text Quality, neither does a CWI course, specifically designed for creative writing.

For Writing Speed no transfer effect to argumentative writing was observed in panel 1: the decrease in speed in Creative writing in the CWI group was not mirrored in the Argumentative Tasks.

Carryover effect

A carryover effect of CWI was observed for Argumentative Text Quality: the CWI group from panel 1 outperformed the CWI group from panel 2. Note that contrary to panel 1, in panel 2 we cannot compare the scores on T2 and T3 directly, because of the differences between the tasks that were administered: although tasks at T2 and T3 were similar, there is no guarantee that they were equally difficult. However, we can compare the difference in patterns between T2 and T3 in both conditions.

The group that followed the CWI-AWI sequence outperformed the AWI-CWI group on argumentative text quality on the second posttest (T3) at the end of panel 2. This might indicate that the instruction in creative writing—in panel 1—carried over into the instruction in argumentative writing in panel 2. Students might have applied those skills learned in the creative writing unit (panel 1) spontaneously to the learning tasks in argumentative writing (panel 2). This idea of a possible carryover effect seems to be supported by the results of panel 1, because for the AWI-CWI group the argumentative writing instruction in panel 1 had no effect at all on argumentative Text Quality at the first posttest (T2), while in the CWI-AWI group, we did see an effect of the AWI: argumentative Text Quality improved after instruction in argumentative writing at T3 even though there was no difference in the instruction given, nor in the conditions, tasks, or teachers between both panels.

Another explanation could be that students’ motivation contributed to the improved Text Quality. We saw that students were enthusiastic about the intervention and found the lessons creative. Perhaps this enhanced their motivation for creative as well as argumentative writing, with better texts as a result. This could also explain the difference in effect for the AWI-CWI group: after all, during the instruction in panel 2 they did not benefit from increased motivation for writing through the preceding creative writing instruction.

Interestingly, for Writing Speed, a similar pattern is observed in panel 2: Writing Speed is positively affected in argumentative writing in the CWI-AWI group. This effect is observed in the process as a whole, and in the first interval of the process. The beginning of the process seems most sensitive for changes as result of the intervention. Whether this effect relates to increased student motivation cannot be determined in the current study.

RQ 3: Moderating effects of creative self-concept

Creative Self-Concept (CSC) did not appear to affect Creative or Argumentative Text Quality. It also did not moderate the effect of CWI on Creative Text Quality in panel 1: all students progressed in that panel. However, CSC did moderate the transfer and carryover effects. In all three cases the pattern is the same: the higher the CSC, the stronger the transfer and carryover effect (see Fig. 3), for Text Quality as well as for Writing Speed.

The CSC measure includes concepts such as inquisitiveness, imaginativeness, focus on output, pride in one’s own work, daring to be different, and persistence, which all refer to a willingness to invest in a task. This finding is consistent with what was reported in an earlier writing process study: students’ learner characteristics correlated with their Writing Behavior and with Text Quality. Students who considered themselves creative wrote better texts and students with a positive attitude to writing wrote better texts with a higher writing speed (Ten Peze et al., 2021). It might be that this willingness to invest in a creative task also played a role in participating in the CWI (panel 1) and from panel 1 to panel 2: these students may have enjoyed the writing lessons relatively more, in both panels. However, even if this might be a reasonable explanation, the counter observation is that such an effect of creativity is not observed in the AWI-CWI. The only difference between the two groups was the order of the instructions. Here, we are once again in the dark.

For Writing Speed, the same carryover effect applies to both creative tasks and argumentative tasks in panel 2. In both tasks, texts are written faster when students consider themselves creative. For creative tasks this is in line with our previous research (Ten Peze et al., 2021). More remarkable is that the speed at which they wrote argumentative texts also increased. So, regarding the carryover effects, we can conclude that when writing instruction is offered in which both genres are practiced, the creative-argumentative writing sequence is preferrable to the argumentative-creative one.

Implications for instructional design in literacy

We based the instructional design of the intervention on Schacter et al.’s Creative Teaching Framework (2006). In the field of literacy education not many theories for instruction are available. With the effective application of his theory in the current intervention, we think that this theory, grounded in empirical studies, might receive more attention in the field of literacy studies. In literacy, open tasks are the default, with multiple responses possible. Schacter et al.’s theory is well suited to enable literacy curricula to move from a mainly instrumental focus towards a more creative, humanistic curriculum for writing, reading and literary fiction (McNeil, 2014).

Implications for creative writing in upper secondary education

Based on this study, we see possible implications of creative writing for education. Since practice in creative writing improves the quality of creative texts, in one of our conditions, it might be advantageous to maintain or incorporate creative writing in the curriculum in upper secondary education. Moreover, creative writing in the classroom does not adversely affect argumentative writing. In fact, in the first panel we saw that for argumentative Text Quality it does not matter whether you let students write creatively or argumentatively. For teachers with doubts about creative writing instruction, our results have shown that creative writing instruction can improve the Text Quality of creative texts without detrimental effects on argumentative Text Quality: it does not hurt to write creatively with students. Even when only practicing creative writing, argumentative Text Quality does not seem to deteriorate.

In addition, we see opportunities for combining argumentative and creative writing. Based on the current results, if teachers want to practice both skills, it is preferable to first practice creative writing with students, followed by argumentative writing. In this order, students improve their creative writing skills during the creative writing unit and the argumentative writing unit is likely to benefit from the earlier creative writing lessons and students’ enhanced motivation. This creative-then-argumentative combination appears to lead to the best results for both task types.

Another issue for educational practice might be to invest in students’ attitudes and beliefs, such as Creative Self-Concept and its underlying motivational and affective behaviors. CSC supports the effects of instruction, which results in more effective instruction and transfer potential.

Considerations

Ecologically valid studies are rarely perfect, and neither is this one. For example, the students all came from one school. However, the advantage is that we were sure that all the students had limited experience with creative writing and had never been taught how to write short stories. As a result, we are almost certain that the effects are attributable to the lesson series and not to differences in prior teaching.

Students wrote their texts by hand during the lessons and on the computer during the pre- and post-measurements. Although the medium obviously affects the writing process, this has no serious implications for our study because all measurements were written in exactly the same way: on the computer in MS Word. Moreover, students in the Netherlands are used to this difference in medium: during classes they often write by hand and on the computer during tests.

One might doubt our use of a switching panel design. If we had set up an experimental study (only panel 1), our results would have been quite straightforward to interpret. Adding panel 2, however, had the advantage that all participants could profit from the extra instructional efforts put into the experimental program at the cost of constructing one extra measurement task (T3). Adding panel 2 creates the possibility of a replication, with the same materials, and, when two courses are implemented (CWI versus AWI), it becomes possible to study the sequence effect of the courses. However, in the current study, we could not maximize the profits of a switching replication design, because the test tasks in panel 2 were not counter balanced.

Beghetto and Karkowski (2017) recommend that studies investigating the role of beliefs to predict creative performance should examine all three key Creative self-beliefs: Creative Self-Concept, Creative Self-Efficacy and Creative Metacognition. However, we only investigated Creative Self-Concept in this study, because of its existing relationship with writing performance (Ten Peze et al., 2021) and the fact that it was the only one of the three beliefs for which a suitable validated questionnaire was available. For follow-up research, we recommend measuring all three beliefs to help further clarify the influence of these beliefs on students’ creative writing performance.

Although we were able to demonstrate an effect of instruction in creative writing with six full lessons, the focus here was on micro-stories. Therefore, for follow-up research we recommend developing instructional materials that can provide additional instruction, teach students to write longer texts, and encourage them to spend more time writing (Graham et al., 2016). This is particularly important if students are not used to writing fiction. Furthermore, from an educational perspective it might be interesting to also investigate what students can learn from more experienced creative writers and how creative writing might influence students’ reading processes, particularly for fictional or literary texts.

Finally, the Inputlog data show how students wrote, but because they only reflected students’ actions, we do not know what students were thinking while they wrote. It would be valuable to gain more insight into students’ thought processes while writing creative texts. However, that was not possible in the current study given the design of this ecologically valid study: a realistic educational context, with real classes and teachers, but it would be a promising idea for follow-up research.

Conclusion

According to Sternberg creative writing is hard to study because participants in creativity research simply do not always have creative ideas at the time of participation, creativity is difficult to assess, and research on creativity is interdisciplinary (2009, p. 15). Despite these difficulties we sought to explore creative writing in an authentic school context. We presented a creative writing learning unit, based on design principles from the literature on creative teaching. The focus was on divergent thinking in the context of the writing tasks and on imagination. We examined the creative writing product (Text Quality), process (Writing Speed) and person (Creative Self-Concept). Regarding the product, the results of our study are mixed: in panel 1, creative Text Quality improved after creative writing instruction, but no such effect was found in panel 2.

Moreover, we found both a pseudo-transfer and a carryover effect from creative writing to argumentative writing. In panel 1, students wrote argumentative texts after creative writing instruction which were just as good as those written by students who received instruction in argumentative writing. And students with confidence in their own creativity write better argumentative texts when they first receive creative writing instruction followed by argumentative writing instruction.

For Writing Speed, we found a decrease in speed for creative writing in panel 1, except for students with relatively high Creative Self-Concept (CSC), and an increase in panel 2. Differences in CSC levels play a role in carryover effects from CWI to AWI: the higher the CSC, the larger the effect of the CWI-AWI group on creative and argumentative Text Quality and Writing Speed in both types of tasks. Therefore, there appears to be no harm in strengthening students’ CSC, and one way to do that may be through creative writing. This can benefit their CSC and motivation and perhaps lead to better creative and argumentative texts.

Despite the fact that creative writing is often considered hard to study, we have shown that it is possible to design a creative writing course that influences Text Quality and writing processes in terms of speed, although further studies are needed.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1979). Effects of external evaluation on artistic creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.2.221