Abstract

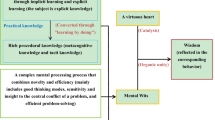

Recent models of wisdom in philosophy and psychology have converged on conceptualizing this intellectual virtue as involving metacognitive processes that enable us to know how to live well and act morally. However, these models have been critiqued by both philosophers and psychologists on the grounds that their conceptions of wisdom are redundant with other constructs, and so the concept of wisdom should be eliminated. In reply, I defend an account of wisdom that similarly conceptualizes wisdom as involving metacognitive processes, but without being subject to the critique that wisdom is redundant. To isolate what’s unique about wisdom, I examine the self-regulatory processes that are relevant for being effective in striving to achieve our goals and draw further insights from the research on skill acquisition and expertise. This framework reveals that the unique contribution that wisdom can make beyond these other processes is in setting and revising our conceptions of living well and the constitutive virtues, and so the concept of wisdom is not redundant. In addition, this account can help to resolve two other areas of contention in wisdom research, which is accounting for the connection between wisdom and moral motivation, as well as the role of emotion in wisdom. A goal-oriented approach provides insight into factors influencing moral motivation due to distinctions in the ways goals are formulated, and for a better understanding of the connection between emotion and wisdom I endorse enactivist accounts that maintain that emotions are embodied appraisals connected to our deeply held cares and values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It’s worth noting that this section will tie together several psychological theories that are usually discussed in isolation from each other (despite them all being related to goal-oriented behavior and self-regulation).

Thus, a goal goes beyond merely valuing a particular state of affairs by creating a discrepancy to work towards reducing. For example, I may ‘value’ having world peace without committing myself to doing anything to achieve it, and so it wouldn’t count as a goal.

While CLT often poses these construals as being on opposite ends of a continuum (i.e., ‘high’ vs. ‘low’), Grossmann et al. (2023) provide evidence from cognitive science that suggests these are better thought of as complimentary perspectives, such that we benefit from thinking both in abstract and concrete terms about a course of action. They also found further support that “abstractness also uniquely related to desirability concerns and concreteness to feasibility concerns”. Since desirability and feasibility are not conceptualized as opposite points on a continuum in self-regulatory theory, and insofar as abstract and concrete construals are differently aligned with desirability and feasibility considerations, then I think that constitutes a further reason to avoid conceptualizing abstract and concrete construals as being opposites on a continuum (and so is probably also a reason to jettison the framing of them as ‘high’ and ‘low’ level construals).

Technically, the CWM is meant to describe key elements of wisdom that are common across a number of different theories of wisdom, rather than to create an entirely new model of wisdom. As such, the CWM identifies elements of wisdom that are also common to the APM. But the APM has been presented as an alternative to the CWM, mainly by focusing on what is seen as lacking in the CWM—a stronger moral grounding for wisdom that’s also relevant for moral motivation, and a more precise connection between wisdom and emotion. On the one hand, if these elements are lacking in the CWM simply because they weren’t common across enough different theories of wisdom, then that’s not really a fault of the CWM. On the other hand, proponents of the APM are claiming that we aren’t really capturing wisdom if these elements are left out of our models. So, there has developed an active debate about what elements should be central to any account of wisdom. I take it that even the proponents of the CWM have engaged in this kind of debate to some extent. For example, the two models disagree about the role of emotion regulation in wisdom, and on the CWM it’s not just a coincidence that most accounts of wisdom have so far not included emotion regulation in the construct of wisdom, but rather that there are reasons to resist including it. My thanks to an anoynomous reviewer for pressing this point.

Ardelt raises a similar worry in a document cited in Grossmann et al. (2020a p. 108, footnote 1), see “Points of Divergence” on OSF at https://osf.io/c37yh. This is in contrast to the “Berlin Wisdom Paradigm” which considers wisdom to be merely expert knowledge (Baltes and Staudinger 2000).

However, there may be plausible anti-realist accounts that are consistent with the claim that wisdom involves making apt value judgments. If so, that’s good news, as it’s one less theoretical commitment to worry about for wisdom researchers.

Here it’s important to note that both Miller and Lapsley’s critiques were aimed specifically at the neo-Aristotelian “standard model of phronesis”, and, according to the APM, “[t]he “standard model” aspires to remain as close to Aristotle’s original texts as possible but elaborate on those in light of various modern social scientific findings” (Kristjánsson and Fowers 2022, p. 4). As a neo-Aristotelian virtue theorist, I find much of value in Aristotle’s work. However, I don’t see why remaining as close to his texts “as possible” should be a desideratum when it comes to the study of wisdom, as I see no relevant grounds for preferring a construct of wisdom based on how well it fits with Aristotle’s original texts. While my account of wisdom and virtue is neo-Aristotelian inspired, I don’t intend to provide a strict reconstruction of Aristotle’s conception of phronesis as the APM does.

Though some virtue theorists endorse the view that there’s only a singular virtue to be acquired rather than discrete virtues (Annas 2011; McDowell 1998). De Caro et al. (2018) do so as well and label that virtue as practical wisdom and conceive of it as ethical expertise. While their skill approach has some overlap with the account I offer in this paper, I resist claiming there’s only a singular skill of virtue to acquire. First, there’s a conceptual problem in that a singular virtue approach is inconsistent with how hierarchies of goals work. For example, the decathlon example is a useful illustration of the fact that there is an overall unity to training for and competing in a decathlon, but it’s still the case that you’re acquiring 10 separate skills. The singular virtue account would, by analogy, seem to suggest implausibly that you’re only acquiring 1 skill. Second, there’s a practical problem for how such a singular skill would be acquired. Skills require feedback for improvement, and if we envision virtue as a singular skill in living well, then it will be difficult to receive much direct feedback on how we’re doing with respect to that very abstract and long-term goal from actions that we take on a day-to-day basis. But conceiving of virtues as proximate constitutive subgoals solves that problem.

This is an example where the CWM suggests not only that emotion and self-regulatory characteristics aren’t common to wisdom, but also that they ought not to be included in the construct of wisdom.

The authors of that research concluded that relevant factors included self-identity, family support, and institutional dynamics.

Here ‘self-control’ means narrowly staying focused on a more valued goal that one is currently striving to achieve, usually by resisting temptations to pursue some less valued but easier achieved goal instead. So, ‘self-control’ is one part of self-regulation, specific to goal striving in action.

My thanks to Igor Grossmann for pointing out that another way to understand the supposed “gap” between moral judgment and action is that it’s an epiphenomenon of a broader problem in social psychology research which is that our attitudes often don’t match our behavior more generally. For meta-analyses and reviews, see Bohner and Dickel 2011; Glasman and Albarracín 2006; and Webb and Sheeran 2006. For just a few of numerous examples of challenges and strategies to reduce the gap between attitudes and behavior, see Arbuthnott 2009; Mutter et al. 2020; and Schill and Shaw 2016.

As evidence of the ambiguity, one APM article starts off with: “‘I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do, I do not do. But what I hate, I do.’ The Apostle Paul (Romans, 7:15) neatly sums up here the perennial gap between moral knowledge and moral action that continues to haunt moral psychologists and moral educators.” (Darnell et al. 2019, p. 101). This quote is about how Paul doesn’t understand why he isn’t acting in accordance with his considered judgment (i.e., a failure in goal striving or self-control), but that’s different from what’s “haunting” psychologists and educators—namely the difficulty in explaining and predicting moral behavior based off of someone’s reported moral judgments.

If people act in ways that defy our expectations or predictions of their behavior, that isn’t necessarily due to people exhibiting inconsistency, as it could be instead that we didn’t have a precise enough understanding of the content of their goals to know what we ought to have expected of their behavior.

However, as Bandura’s (1999) work on moral disengagement has shown, whether internalized standards can effectively guide conduct depends in large part on the activation of these self-regulatory mechanisms, especially self-sanctioning feelings which help to deter immoral actions.

In personal communication, one of the contributors to the APM suggested that their view of cognition being bound up with emotion is actually closer to the enactivist view than it appears here, but also acknowledged that some of their choice of terminology and phrasing has obscured their view.

References

Achtziger A, Gollwitzer PM (2007) Motivation and volition in the course of action. In: Heckhausen J, Heckhausen H (eds) Motivation and action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 202–226

Annas J (2006) Virtue ethics. In: Copp D (ed) The Oxford handbook of ethical theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 515–536

Annas J (2011) Intelligent virtue. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Arbuthnott KD (2009) Education for sustainable development beyond attitude change. Int J Sustain High Educ 10(2):152–163

Arvanitis A, Stichter M (2023) Why being morally virtuous enhances well-being: a self-determination theory approach. J Moral Educ 52(3):362–378

Baltes PB, Staudinger UM (2000) Wisdom: a metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. Am Psychol 55(1):122–136

Bandura A (1999) Social cognitive theory of personality. In: Pervin LA, John OP (eds) Handbook of personality: theory and research. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 154–196

Batson CD (2017) Getting cynical about character: a social-psychological perspective. In: Christian BM, Sinnott-Armstrong W (eds) Moral psychology: virtue and character. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 11–44

Bauer JJ, King LA, Steger MF (2019) Meaning making, self-determination theory, and the question of wisdom in personality. J Pers 87:82–101

Bohner G, Dickel N (2011) Attitudes and attitude change. Ann Rev Psychol 62(1):391–417

Carver CS, Scheier MF (1990) Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychol Rev 97(1):19–35

Carver CS, Scheier MF (2003) Self-regulatory perspectives on personality, in millon, theodore and lerner. Handbook of psychology: personality and social psychology. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 185–208

Clark A (2015) Surfing uncertainty—prediction, action, and the embodied mind. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cornwell JF, Higgins ET (2015) Approach and avoidance in moral psychology: evidence for three distinct motivational levels. Pers Indiv Differ 86:139–149

Darnell C, Gulliford L, Kristjánsson K, Paris P (2019) Phronesis and the knowledge-action gap in moral psychology and moral education: a new synthesis? Hum Dev 62(3):101–129

De Caro M, Vaccarezza MS, Niccoli A (2018) Phronesis as ethical expertise: naturalism of second-nature and the unity of virtue. J Value Inq 52:287–305

Ericsson KA (1996) The road to excellence. Laurence Erlbaum, Mahwah

Fridland E (2014) Skill learning and conceptual thought: making a way through the wilderness. In: Bashour B, Muller H (eds) Philosophical naturalism and its implications. Routledge, Oxford

Fridland E, Stichter M (2020) It just feels right: an account of expert intuition. Synthese 199:1327–1346

Fujita K, Trope Y, Liberman N, Levin-Sagi M (2006) Construal levels and self-control. J Pers Soc Psychol 90(3):351–367

Glasman LR, Albarracín D (2006) Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: a meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol Bull 132(5):778–822

Glück J (2018) Measuring wisdom: existing approaches, continuing challenges, and new developments. J Gerontol: Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73(8):1393–1403

Gollwitzer PM (1990) Action phases and mind-sets. In: Tory EH, Sorrentino RM (eds) Handbook of motivation and cognition, vol 2. Guilford Press, New York, pp 53–92

Greene JA, Azevedo R (2009) A macro-level analysis of SRL processes and their relations to the acquisition of a sophisticated mental model of a complex system. Contemp Educ Psychol 34(1):18–29

Grossmann I (2017) Wisdom in context. Perspect Psychol Sci 12(2):233–257

Grossmann I, Weststrate NM, Ardelt M, Brienza JP, Dong M, Ferrari M, Fournier MA, Hu CS, Nusbaum HC, Vervaeke J (2020a) The science of wisdom in a polarized world: knowns and unknowns. Psychol Inq 31(2):103–133

Grossmann I, Weststrate NM, Ferrari M, Brienza JP (2020b) A common model is essential for a cumulative science of Wisdom. Psychol Inq 31(2):185–194

Grossmann I, Peetz J, Rotella A, Buehler R (2023) The wise mind balances the abstract and concrete. https://psyarxiv.com/5ce6x/

Horn J, Masunaga H (2006) A merging theory of expertise and intelligence. In: Anders K, Ericsson (eds) The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 587–612

Kanat-Maymon, Roth G (2015) The role of basic need fulfillment in academic dishonesty: a self-determination theory perspective. Contem Educ Psychol 43:1–9

Krettenauer T (2022) When moral identity undermines moral behavior: an integrative framework. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 16(3):e12655

Krettenauer T, Stichter M (2023) Moral Identity and the acquisition of virtue: a self-regulation view. Rev Gener Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680231170393

Kristjánsson K, Fowers B (2022) Phronesis as moral decathlon: contesting the redundancy thesis about phronesis. Philos Psychol 37(2):279–298

Kristjánsson K, Fowers B, Darnell C, Pollard D (2021) Phronesis (practical wisdom) as a type of contextual integrative thinking. Rev Gen Psychol 25(3):239–257

Lapsley D (2019) Phronesis, virtues and the developmental science of character. Hum Dev 62(3):130–141

Lapsley D (2021) The developmental science of phronesis. In: Vaccarezza MS, De Caro M (eds) Practical wisdom: philosophical and psychological perspectives. Routledge, Oxford, pp 138–159

Liberman N, Trope Y (1998) The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: a test of temporal construal theory. J Personal Soc Psychol 75:5–18

Maiese M (2014) How can emotions be both cognitive and bodily? Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 13:513–531

Maiese M (2017) Transformative learning, enactivism, and affectivity. Stud Philos Educ 36:197–216

McDowell J (1998) Virtue and reason. In: McDowell (ed) Mind, value, and reality. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Miller CB (2021) Flirting with skepticism about practical wisdom. In: Vaccarezza MS, De Caro M (eds) Practical wisdom: philosophical and psychological perspectives. Routledge, Oxford, pp 52–69

Mutter ER, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM (2020) An online randomised controlled trial of mental contrasting with implementation intentions as a smoking behaviour change intervention. Psychol Health 35(3):318–345

Narvaez D, Lapsley D (2005) The psychological foundations of everyday morality and moral expertise. In: Lapsley DK, Clark Power F (eds) Character psychology and character education. University of Notre Dame Press, Indianapolis, pp 140–165

Piaget J (1970) Piaget’s theory. In: Mussen PH (ed) Carmichael’s manual of child psychology. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 703–732

Ridderinkhof KR (2017) Emotion in action: a predictive processing perspective and theoretical synthesis. Emot Rev 9(4):319–325

Roos P, Botha M (2022) The entrepreneurial intention-action gap and contextual factors: towards a conceptual model. South Afr J Economic Manage Sci 25(1):a4232

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2017) Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publishing, Oxford

Schill M, Shaw D (2016) Recycling today, sustainability tomorrow: effects of psychological distance on behavioural practice. Eur Manag J 34(4):349–362

Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ (1999) Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. J Personal Soc Psychol 76(3):482–497

Stichter M (2018) The skillfulness of virtue: improving our moral and epistemic lives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stichter M (2020) Learning from failure: shame and emotion regulation in virtue as skill. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 23:341–354

Swartwood J (2013) Wisdom as an expert skill. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 16:511–528

Trope Y, Ledgerwood N, Liberman N, Fujita K (2020) Regulatory scope and its mental and social supports. Perspect Psychol Sci 16:1–21

Valle M, Kacmar K, Michele, Zivnuska S (2019) Understanding the effects of political environments on unethical behavior in organizations. J Bus Ethics 156:173–188

Webb TL, Sheeran P (2006) Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull 132(2):249–268

Wilkinson S (2019) Getting warmer: predictive processing and the nature of emotion. In: Candiotto L, George D, Kathryn N, Andy C (eds) The value of emotions for knowledge. Springer, New York, pp 101–119

Wolf S (2007) Moral psychology and the unity of the virtues. Ratio 20(2):145–167

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Maria Silvia Vaccarezza, Michel Croce, and the Aretai Center on Virtues for this opportunity; Colin Allen and the Machine Wisdom Project for their support in the initial stages of writing this paper; and Igor Grossmann for valuable feedback on a later draft of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work, and the author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stichter, M. Flourishing Goals, Metacognitive Skills, and the Virtue of Wisdom. Topoi (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-024-10013-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-024-10013-2