Abstract

Our paper is concerned with theories of direct perception in ecological psychology that first emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. Ecological psychology continues to be influential among philosophers and cognitive scientists today who defend a 4E (embodied, embedded, extended, enactive) approach to the scientific study of cognition. Ecological psychologists have experimentally investigated how animals are able to directly perceive their surrounding environment and what it affords to them. We pursue questions about direct perception through a discussion of the ecological psychologist’s concept of affordances. In recent years, psychologists and philosophers have begun to mark out two explanatory roles for the affordance concept. In one role, affordances are cast as belonging to a shared, publicly available environment, and existing independent of the experience of any perceiving and acting animal. In a second role, affordances are described in phenomenological terms, in relation to an experiencing animal that has its own peculiar needs, interests and personal history. Our aim in this paper is to argue for a single phenomenological or experiential understanding of the affordance concept. We make our argument, first of all, based on William James’ concept of pure experience developed in his later, radical empiricist writings. James thought of pure experience as having a field structure that is organized by the selective interest and needs of the perceiver. We will argue however that James did not emphasize sufficiently the social and intersubjective character of the field of experience. Drawing on the phenomenologist Aron Gurwitsch, we will argue that psychological factors like individual needs and attention must be thought of as already confronted with a social reality. On the phenomenological reading of affordances we develop, direct perception of affordances is understood as taking place within an intersubjective world structured by human social and cultural life.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The concept of affordances was first coined by the ecological psychologist James Gibson to refer to the possibilities for action offered by the environment (Gibson 1979/2014). In ecological psychology, affordances are taken to be directly perceivable by animals. We will henceforth understand ‘direct perception’ as the pragmatic contact of the animal with its surrounding reality as manifested in the animal’s experience.Footnote 1 For ecological psychologists, perception is an exploratory activity of the whole animal involving, in the case of visual perception, the movement of its eyes, head and torso. Ecological psychologists reject a common understanding of perceptual systems in cognitive psychology as sub-personal systems whose receptors are mechanically stimulated by sensory stimuli to produce sense impressions. Cognitive psychologists typically argue that such sensory impressions must be enriched and transformed by information processing to construct inner representations that form the basis for an animal’s perception of the world. Ecological psychologists argue by contrast that perceptual systems work in tight coordination with action systems for the detection and use of affordances - the possibilities for action an environment furnishes to the animals that live in it (Gibson 1979/2014). Affordances are directly perceivable because the ambient energetic arrays, that perceptual systems are tuned to over the course of an animal’s development, can be used by animals to coordinate with what the environment affords to them.

The focus of our paper is on the claim that the affordances of an animal’s environment can be directly perceived. The concept of affordances has proved to be influential in a wide variety of fields from philosophy, psychology, robotics and neuroscience to sustainability research, design and media studies. Affordances are increasingly understood by philosophers and psychologists in relational terms that cut across dualities of knower and known, subject and object, or animal and environment (Heft 1989, 2001, 2003; Costall 1995, 2004; Stoffregen 2003; Chemero 2003, 2009; Rietveld and Kiverstein 2014; Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014; Van Dijk and Rietveld 2017; Bruineberg et al. 2023). Much of the scientific research in ecological psychology is based on a different understanding of affordances as dispositional properties belonging to the physical world. Dispositional theories take affordances to be actualised in the presence of animals in possession of the right “effectivities” (see e.g. Turvey 1992; cf. Heras-Escribano 2019). For example, a branch affords perching on to a bird with effectors that support perching. The dispositional and relational analyses of the affordance concept have been argued to be consistent (Chemero and Turvey 2007). We will argue for a phenomenological account that defines what it is for affordances to exist in relation to experience. This phenomenological understanding of affordances would count against dispositional theories that take affordances to be experience-independent properties of physical objects. Affordances, we will argue, do not belong to the physical world, as dispositional theorists argue, but to the world in relation to experiencing animals.

In recent years, relational theorists have begun to mark out two explanatory roles for the affordance concept (e.g. Rietveld et al. 2018; Baggs and Chemero 2019, 2021). In one role, affordances are cast as belonging to a shared, publicly available environment that has an existence independent of the experience of any perceiving and acting animal. In a second role, affordances are described in phenomenological terms, in relation to an experiencing animal that has its own peculiar needs, interests and personal history. Our aim in this paper is to argue for a single phenomenological understanding of the affordance concept. To understand the affordance concept in phenomenological terms is to take the relation between animals and their environments that is constitutive of affordances to be experiential in nature.

We argue for a phenomenological account of affordances first of all based on William James’ concept of pure experience developed in his later, radical empiricist writings. Gibson’s account of direct perception has been convincingly argued to be the direct descendant of James’ radical empiricism (Heft 2001). We will follow James’ scholars who offer a phenomenological interpretation of the concept of pure experience. The phenomenological character of radical empiricism can be noticed already in its main thesis that every theoretical investigation shall only refer to “things definable in terms drawn from experience” (James 1909/1975 pp. 6–7).Footnote 2 We will suggest that James introduced the concept of pure experience with the aim of describing the fundamentally direct, non-dual and pragmatic way in which animals relate to their surroundings (see Seigfried 1976, 1990; Krueger 2022). James argued that all things or qualities that appear to the mind in pure experience, do so within a “halo of felt relations” (1890a, p.256). These felt relations are sets of interrelated possibilities, some inarticulate and indeterminate, that are implied by whatever is immediately given in sense experience. Whatever we can experience, we experience in the context of a horizon of felt relations that give a sense of direction or tendency to what is immediately experienced. We will use the phenomenological concept of the horizon to analyse the sense in which affordances are possibilities and potentialities that are given in experience.

We go on to argue that James did not emphasize sufficiently the social and intersubjective character of pure experience. James thought of pure experience as having a field structure that is organized by the selective interest and needs of the individual perceiver. Drawing on the phenomenology of perception of Aron Gurwitsch we will argue that factors like individual needs and attention must be thought of as already confronted with a social reality that provides structure to the field of consciousness. Relational theories recognize that affordances are social, cultural and material, and that the abilities for acting on affordances are developed through a process of continuous social feedback (Gibson 1966, 1979/2014; Reed 1996; Heft 2001, 2007 Rietveld 2008; Baggs and Chemero 2019; Van den Herik 2021; Baggs 2021). We show how work in social phenomenology also highlights the social and cultural organization of individual experience. We use the work of the social phenomenologists to show how the experience of affordances has a field structure organized by human social and cultural life.

2 Two Senses of the Environment in Gibson and his Followers

In a well-known passage, Gibson defined affordances as what the environment “offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill” (1979/2014, p.121). For example, trees may be climbable for squirrels that are able to clamber up their trunks. Water is drinkable, berries are edible, grass is walk-on-able if one is in a public space in which this is permitted, and so on. Gibson insisted on two claims concerning affordances: (1) affordances are real; (2) affordances can be directly perceived because ambient energetic arrays are structured in ways that can be used for detecting them. In what follows we will mostly be concerned with this first claim.

What does it mean to say that affordances are real? Gibson wrote that an affordance is “neither an objective property nor a subjective property; or it is both if you like” (Gibson 1979/2014, p. 121). An affordance can be both subjective and objective because it is neither on its own - it is instead a relation between animals as experiencing beings and their surrounding environments. James (1912/1976: p.10) described the term “experience” as a “double barrelled word” because the term, properly understood, does not recognize a division between subject and object but contains them both in a single integrated, undifferentiated unity. Subjects and objects refer to products that can be separately discerned in experience only in acts of reflective judgement. We will suggest that the relational theory of affordances is best understood as describing experienced relations of animals to their environments. Life, just like experience, is a “double-barrelled” activity in which animals and their environments form a single integrated unity. Only in reflection upon such undifferentiated activities does life “break up into external conditions - air breathed, food taken, ground walked upon - and internal structures - lungs respiring, stomach digesting, legs walking.” (Dewey 1958: p.11).

Philosophers defending a relational interpretation of affordances have however mostly resisted understanding the existence of affordances in experience-dependent or phenomenological terms.Footnote 3 They have tended to distinguish between affordances as they are experienced by individuals and affordances that are available in the environment to be detected by any creature with the ability to perceive and act on them. Based on this distinction here has been a good deal of attention given to the question of why some affordances solicit or invite action while others do not (see e.g. Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014; Rietveld et al. 2018; Dings 2018; Withagen et al. 2017; Withagen 2022, 2023). In addressing this question, proponents of the Skilled Intentionality Framework (SIF) have made a distinction between the landscape and field of relevant affordances (de Haan et al. 2013; Rietveld and Kiverstein 2014; Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014; Rietveld et al. 2018). The landscape is the set of affordances available in an ecological niche of a form of life. They borrow the notion of ‘form of life’ from Wittgenstein (1953) who used this concept to refer to relatively stable and regular patterns of activity within communities and groups of animals. The field of relevant affordances, by contrast, is made up of multiple affordances that are experienced by an individual animal as inviting because they bear in some way on an activity this individual is engaged in performing. Thus, when I have an appointment on the other side of town, my bicycle might offer the inviting affordance of riding, or a passing taxi may solicit me to hail it down (Dreyfus and Kelly 2007; Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014; Rietveld and Kiverstein 2014; De Haan et al. 2013; Withagen et al. 2012, 2017; Withagen 2022, 2023).

In a recent pair of papers, Baggs and Chemero have made a similar distinction between two senses of environment, which they argue were conflated in Gibson’s later writings on affordances (Gibson 1979/2014). Gibson distinguished the environment from the physical world, understanding the environment as the physical world scaled to the perception and action systems of the organisms that inhabit it. However, Baggs and Chemero argue that Gibson ought also to have made a further distinction between the ‘habitat’, which they define as the physical world considered in relation to the typical member of a species of animal, and the ‘Umwelt’ - the habitat considered from the point of view of a particular experiencing animal. The affordances of the habitat are, they argue, persisting resources that continue to exist across generations, exerting selection pressure on the animals that live in this habitat (see also Reed 1996). The subset of affordances belonging to the umwelt, by contrast, serves a similar explanatory purpose to the concept of the field of relevant affordances in SIF. The umwelt forms in the midst of an animal’s activities, and is introduced to account for how affordances are experienced by individuals for whom they are relevant. Consider for instance a pilot that has learned to fly a plane. When she masters this skill, her umwelt becomes richer and the qualitative experience of the flight deck changes. She may, for instance, start to experience a bodily readiness to perform actions when a light appears that was not present before. Baggs and Chemero claim that an account of the habitat cannot provide a proper description of learning processes since, even if its structure remains unaltered, from the perspective of the pilot “learning results in a richer experience of the world” (Baggs and Chemero 2019, p.14).

Neither the concept of an umwelt nor the field of relevant affordances refers to a private phenomenal reality. Instead these concepts are best understood as capturing the perspective of an individual animal in relation to a broader shared environment. The umwelt/field is made up of a sub-set of affordances that belong to the habitat/landscape. The shared environment, understood either as a landscape or as a habitat, is however described in experience-independent terms. For Baggs and Chemero, for instance, the habitat is taken to be the physical world considered in relation to a typical member of a species. In SIF, the landscape of affordances are defined in relation to forms of life understood as relatively stable behavioural regularities within groups of agents. In neither case is the shared environment of affordances understood ontologically in relation to experience. If the affordances belonging to the umwelt or field are understood as a subset of those belonging to the habitat or landscape, it follows that the umwelt or field must also ultimately be explained in physicalist or behavioural terms.

We agree with these philosophers that the field/umwelt should be thought of as forming a sub-set of a more encompassing landscape/habitat. Affordances belonging to the field/umwelt do not have a special ontological status distinct from those belonging to the landscape/habitat. However, we suggest that the affordances belonging to the umwelt/field have an existence that is experience-dependent. The phenomenological account of affordances we will go on to propose argues that the affordances belonging to the shared environment, whether conceived of as a habitat or as a landscape, should also be thought of as experiential in nature. We will make this argument by returning to the historical roots of the concept of affordance in Wiliam James’ philosophy. More specifically, we start from James’ notion of pure experience developed in his posthumously published Essays in Radical Empiricism (James 1912/1996). Pure experience, as we will read it, is a phenomenological concept that captures the fundamentally non-dual, pragmatic way in which animals relate to their surroundings (Seigfried 1976, 1990; cf. Krueger 2022).

3 A Phenomenological Reading of James’ Notion of Pure Experience

In the passage we quoted from above Gibson tells us his notion of affordance “cuts across the dichotomy of subjective-objective”. He goes on to add that an affordance “is equally a fact of the environment and a fact of behavior. It is both physical and psychical, yet neither.” (Gibson 1979/2014 p.121). We have suggested above that affordances can be “equally facts of the environment” and “of behavior” because they have the metaphysical status of relations. The notion of relation required for understanding what affordances are has previously been analysed in linguistic terms by proponents of the relational theory of affordances. Chemero (2009) for instance compares the notion of relation needed for understanding the reality of affordances with the relation “taller-than” that holds between two individuals – John and Mary. The property is such that neither individual can possess it by themselves but it depends on the heights of each of them. Similarly, Chemero has argued affordances have the logical status of two-place relations whose existence depends on both “features” of particular situations, on the side of the environment, and the abilities of individuals on the side of animals that are capable of perceiving and acting on affordances.

We propose to understand the notion of relation needed for understanding affordances in experiential terms. We do so based on James’ notion of pure experience. James argued against what he dubbed “mind stuff theory” - the view that experience is made up of finite, discrete atoms or elements of sensations such as colour, taste, smell, hardness and so on. James argued instead that all relations, including those between knower and known, belong to immediate or pure experience. Pure experience is not built from elementary sensations but is an “extremely complex reticulation” (James 1912/1996, p.140) extended in space and time. For James, relations are experienced as tendencies or resistances manifesting a sense of continuity, more or less extended in time. For instance, we never experience just the sound produced by a clap of thunder, but rather a “thunder-breaking-upon-silence-and-contrasting-with-it” (James 1890a: p.240). No intellectual categories or principles of association are necessary to account for the connectedness and continuity of experience. Relations are an integral part of experience. Similarly, relations are also spatial, for example, the material of which a book is constituted, its colour, its location on a desk, its relations with the other objects in the surroundings. Relations can also be evaluative and aesthetic concerning the emotional meaning or significance a specific object has for a subject - for example whether the object elicits pleasure or aversion, a person’s memories of the object, their expectations and interests, etc.

Pure experience is always an experience of a “teeming multiplicity of objects and relations” (1890a, p.224). When we experience particular things or qualities James thought this is because the object or quality interests us in some practical or aesthetic way and has therefore been selectively made into an object of attention. What attention selects from is however a flux of sensible experience. Every discrete thing or quality appears from within “a halo of felt relations” (1890a, p.256) which can vary in its reach or extent in space and time. James used the concept of ‘field’ to characterize the organization of experience. In Chap. 9 of the Principles, the field is described as always having a centre, which he labelled “focus” or “theme”, and a periphery, which he referred to as the “margin” or “fringes”.Footnote 4 While the focus is what engrosses the perceiver’s mind and has a clear and privileged place in the field, fringes are described as a “psychic overtone” or “suffusion” permeating the situation. Fringes are explicitly described as an indefinite number of relations that implicitly make the perceiver aware of the context in which the focus is situated. The meaning of the focus is always determined by the relations present in the margin. In other words, fringes necessarily determine the contextual understanding of the focus that is experienced as strongly connected with the other relations within the field or otherwise fully discordant with them.

James’ notion of pure experience is sometimes given a metaphysical interpretation as characterizing the intrinsic nature of material reality (see e.g. Lamberth 1999; Cooper 2002; Goodman 2017). Gibson, for instance, seems to have had such a reading in mind in describing affordances as having a reality that is “neither physical nor psychical” (1979/2014, p.121). The metaphysical reading of pure experience takes James to be claiming that the intrinsic nature of material reality is neither fundamentally physical nor mental but is experiential. Matter is made from a kind of stuff - pure experience - that is neutral between the two metaphysical categories of mental and physical.

We will read James’ concept of pure experience, in metaphysically-neutral, phenomenological terms as describing the fundamentally nondual and pragmatic way in which subjects directly experience their surroundings in the flux of life.Footnote 5 In common with Husserl, the phenomenological reading of pure experience takes James to seek grounding in the facts of human experience for the objective claims of science and the metaphysical claims of philosophers. Radical empiricism is a methodological directive to “restrict our universe of philosophical experience to what is experienced or, at least, experienceable” and not to make any judgements about non-experienced objects (1912/1996, p.243). This directive bears a close resemblance to Husserl’s epoché that invites us to set aside all of our presuppositions about our relationship with the world in order to reflect upon what is immediately and directly given in lived experience. Phenomenological readings of James take him to be describing, without metaphysical prejudice, the structure or organization of pre-reflective moments of experience in which a subject is practically and emotionally involved with the world.

James’ concept of the fringe of felt relations that surrounds all things and qualities present in pure experience anticipates what Husserl would later refer to as the “perceptual horizon” (Husserl 1960, 1989, 2001). Husserl used the term ‘horizon’ to refer to the set of interrelated possibilities that surround each object of perception, including potential activities the object makes possible (i.e. the object’s affordances). For example, when you look at a sharp knife part of what you see is its potential to cut you - this potential belongs to the knife’s perceptual horizon. The horizon is not sensibly present in immediate experience but is experienced as a set of possibilities that are implied by whatever is sensibly given in experiences. One sees, for example, the profile of a table from a particular angle. Simultaneously, one sees this profile of the table as implying the possibility to walk around the table and view it from different angles, or to sit down at the table and use it to eat from, or to use the surface of the table to write something down on a piece of paper.

We propose to use James’ notion of the fringe of felt relations (and the phenomenological notion of horizon that stems from James philosophy) to analyse the sense in which affordances are perceived as possibilities for action. The possibilities for action that a thing offers are relations one can potentially take up that are implied in one’s perception of the thing as a part of the halo of felt relations that surrounds it. When one sees a book, for example, one sees the possibility to read from the book, but many other possibilities are also implied in what one sees such as the possibility to use the book to prop a door open, or as part of a stack to rest one’s computer on when taking part in a video call.

To summarise what has been argued so far, we have provided an analysis of affordances through a discussion of James’ notion of pure experience that takes subject and object to form a single undivided unity. Affordances are, we have proposed, experienced relations. We have used the phenomenological notion of the horizon to explain what it means to directly perceive a possibility for action. We return now to the claim made by relational theorists that we outlined in Sect. 1 that affordances have an experience-independent reality.

4 The Experience of Affordances

Recall that in the current literature, phenomenology is appealed to by philosophers concerned with the individual lived experience of affordances. Thus, in the SIF, it is the field of relevant affordances that is posited to explain in naturalistic terms the individual’s experience of the environment. Baggs and Chemero introduced the concept of the umwelt to account for the “meaningful, lived surroundings of a given individual” (2019, p.6) It is the umwelt, they tell us, that is given to the individual in experience, and that remains in brackets after the phenomenologist has performed the phenomenological reduction. What they call the “habitat” is known only by taking up the point of view of an idealized typical member of a species. Knowledge of the habitat and the physical world is, they write, “theoretical and inferential”, and as such it remains outside of the scope of phenomenological reflection (Baggs and Chemero 2021, p.S2186). When a researcher makes appeal to affordances that belong to an environment understood either as a habitat or a landscape, the concepts of habitat and landscape are introduced to account for how affordances are available for any creature to act on that is capable of perceiving them. Affordances typically have a relatively stable and persisting existence that means that they are available over time to be potentially perceived by any animal with the necessary abilities. It is doing justice to this feature of affordances that Chemero (2009) argues that affordances have the property of being lovely, which he contrasts, drawing on Dennett (1998), with the property of being suspect. X is lovely if, were an individual to encounter X, they would take it to be so. An object Y is suspect, by contrast, if it is actually under suspicion. Affordances, Chemero suggests, can be said to be lovely in the sense that they have a mode of existence that depends on the possibility of their being observed, but not on any actual act of observation.

The phenomenological theory of affordances we are proposing does not deny that affordances are lovely, existing independent of any actual act of observation. We have been arguing however that the notion of possibility needed for understanding the existence of affordances is prior to any division of subjects from objects. Hence, affordances cannot be said to have the existence of self-sufficient properties of physical objects considered in isolation from experience. This is not to deny that for the purposes of doing laboratory experiments, affordances can be made into objects that can be considered in abstraction from experience. However, when affordances are made into objects of scientific investigation, this is the result of the scientist’s selective interests that lead them to attend to particular affordance in isolation from the underlying teeming multiplicity of objects and relations that is the world of pure experience. We have been arguing that affordances belong first of all to this undifferentiated world of pure experience. When they are made into the objects of scientific scrutiny, this is the outcome of an act of selection for specific scientific purposes.

James made a distinction between different orders of existence: the world of sensible experience, the worlds of the sciences, the imaginary worlds depicted in literature, the supernatural worlds of mythology and religion, the worlds of individual opinion and so on (James 1890b, p.291). In each of these orders of existence, meaning and experienced reality are correlative. Meaning and value are not dependent on acts of reflective judgement but are immediately experienced prior to reflection in part because of the fringes of meaningful possibilities within which each particular thing or quality is experienced. For James, the most fundamental order of reality is the sensible world of experience that forms the foundation for subsequent acts of selection or reflective categorical judgement such as those that are performed in the practice of doing science.

James describes this fundamental order of reality as a “paramount reality”, a term he used to refer to what is perceived to be real by the perceiver. James’ notion of paramount reality is related to what phenomenologists have described as the natural attitude. This attitude is described well by Gurwitsch as “our permanent awareness of our no less permanent belief in the existence of the real (perceptual) world and of ourselves as parts or members of this world” (Gurwitsch 1964/2010, p. 512). What is encountered in James’ paramount reality is experienced as having an existence that is independent of each of us, and our momentary experiences. The paramount reality forms a larger fringe that extends beyond the person’s own individual stream of thoughts. Affordances can be belong to a paramount reality that is experience-independent while also having the property of loveliness as Chemero defines it, and existing independently of any act of observation. We have argued for this claim on two grounds. First, we have proposed that the notion of possibility appealed to in the concept of affordance should be analysed by reference to the fringe of felt relations that belongs to pure experience. Second, we have argued that the affordances belonging to the paramount reality are best understood prior to any distinction or separation of subjects from objects. When we understand affordances objectively in the terms of the natural sciences, this is the result of an act of abstraction in which we selectively attend to an affordances taking it a part from the halo of relations which normally surround it.

Baggs and Chemero may object that when researchers are concerned with what they call “the habitat”, they operate with a dispositional, and not with a relational conception of affordance. They have in fact introduced the distinction between the habitat and umwelt in part to provide a reconciliation between dispositional and relational theories of affordances. When an ecological psychologist designs an experiment that aims to probe the behavioural responses of the average or typical member of a species, they will be targeting affordances as belonging to the habitat. Baggs and Chemero claim that the affordances of a habitat are best conceived of as dispositional properties of physical objects. The dispositional understanding of affordance captures a notion of affordance used in the empirical literature that refers to a relatively persisting structure in the physical world. Affordances as they show up in the umwelt are however continuously undergoing change based in part on the person’s action capabilities” (Chemero 2022 p.46; cf. Chemero 2009 on affordances 2.0). To account for how individuals are able to successfully adapt their actions to fit the demands of a changing environment, researchers will make use of a relational understanding of affordances as features of an umwelt.

First, we should emphasize our agreement with Baggs and Chemero that researchers in ecological psychology often do make use of the concept of affordance in both a dispositional and relational sense. We have been arguing however that the understanding of affordances as dispositional properties of physical objects is an abstraction, the result of an act of selection that takes the affordance in isolation from the paramount reality of sensible experience to which it originally belongs. Baggs and Chemero would seem to agree when they assign an epistemic priority to the umwelt. It is the umwelt, they tell us, that is immediately given in experience, and the physical world is known only through theoretical abstraction from an umwelt. However, we have been arguing that the umwelt, once it is understood as a paramount reality, is already sufficient to account for the phenomenological givenness of stable and persistent affordances. As long as the meaning of an affordance is maintained in the activities of practical life, its existence will also be maintained.

We will finish up our paper by providing a corrective to James’ claim that the field of experience for an individual at any given moment is structured and organized by their selective interests. James describes the field organization of experience as determined by two main principles: The first is the temporal relations within the stream of consciousness. Second, are the selective interests of the perceiver, which we will understand, following Seigfried (1990, p. 84), as being a function of attention, and the emotional and practical attitudes of the perceiver. Following James, the field of experience, as well as its boundaries and overall organization, are shaped only by:

“what I agree to attend to. […] [Selective] Interest alone gives it accent and emphasis, light and shade, background and foreground - intelligible perspective in a word” (James 1890a, pp.380–381).

We direct our attention towards the things and events that have a practical and emotional value for us. Selective interest is described by James as an actual organizing principle behind all our experiences that imposes order on a “big blooming buzzing confusion”, making it possible for us to deal with a multiplicity of objects and relations (1890b, p. 225). For James the relations experienced on the fringes of consciousness differ only in degree. They do not present any qualitative differences since they are arbitrarily established by the perceiver. Following Gurwitsch, we will argue by contrast, that the field of consciousness already possesses an inherent organization. The focus, and its surrounds, manifest qualitative differences related to how the elements experienced are materially and functionally relevant to each other.

5 The Field Organization of Experience

The phenomenological motifs present in James’ radical empiricism were noted by Gurwitsch in a letter to Schutz. Gurwitsch wrote:

“What do you think about this idea? “Pure experience” becomes the noema, world and I two systems ‘’within the experiential realm” and in a certain sense indeed out of the same stuff-namely noematic stuff. The question of consciousness becomes the question of the I in James, and the “stream of experience” is our good old pure consciousness. The moral of the story is not, of course, James = phenomenology, but that a sufficient radicalization of his position leads to phenomenology.”Footnote 6 (Grathoff 1989, p. 39)

Gurwitsch seems to be suggesting in this passage that the phenomenological concept of the noema, employed to analyse the intentional structure of perceptual experience, can be mapped onto pure experience. Husserl defines the noema as the sense (Sinn) of “the perceiving thing as such” (1983). Consider as an example a person seeing a blossoming apple tree. They can view the tree from many perspectives as they approach the tree and walk around it. Each perspective is grasped through what Husserl described as a different “act” of consciousness. Husserl called the perceptual acts that present a subject with an object from a particular perspective, “noetic” acts. In each noetic act, it is one and the same tree that a person experiences. The noema refers to the perceived object - the blossoming apple tree - just as it appears in the person’s visual experience.Footnote 7 The noema is the perceived object itself considered within phenomenological reflection precisely as it is perceived.

The noema, just like pure experience, is prior to any ontological separation of subjects from objects. Gurwitsch described the relationship between the noema and the perceptual manifestations of the actual object (the different noetic acts) as “a relationship between a member of a system and the system itself” (Gurwitsch 1966, p. 146). For both Gurwitsch and James, the separation between the subject-pole and the object-pole of experience is ultimately not given in immediate experience. In pre-reflective experience, there is no dualism in the correlation between noema and different noetic acts since the perceptual object is, following Gurwitsch, nothing more than “apprehension of a system of appearances from the vantage-point of one of its members” (Gurwitsch 1964/2010).

Gurwitsch and Schutz,Footnote 8 were however critical of James’ claim that paramount reality depends on the interests of the individual perceiver. They argued instead that a paramount reality is inherently intersubjective, common to all fellow human beings. The world whose existence we take for granted is inhabited by other people. The presence of other people organizes our daily experiences. The same inherent organization of my experience is connected to others by a multitude of social relationships reflecting the regularities of a social world in which I live and act. To explain why the field of consciousness is organized as it is, we must assume the existence of other people. The field of consciousness for Gurwitsch and Schutz is always organized in ways that reflect an intersubjective reality with a specific social order. Indeed the selective interests of the individual perceiver are arguably a reflection of the intersubjective and socially ordered surroundings inhabited by other people.

Gurwitsch criticized James for focusing exclusively on selective interest as an organizing principle of the field of consciousness, and neglecting how the field is already organized by social and cultural orders.Footnote 9 If attention is taken to bestow on an otherwise “primordial chaos of sensations” a meaningful organization, Gurwitsch argues this leaves unexplained how anything can be selected and be segregated from the rest of the field in the first place. To direct our attention at something, it is necessary to presuppose an already organized field in which some aspects are immediately experienced as salient and qualitatively different from others. James failed to recognize what Gurwitsch called the “autochthonous” organization of the field of experience.

Arvidson traces the etymology of the meaning of the term “autochthonous” to a feature that has sprung from the land itself:

“A mountain, for example, may be called an autochthonous feature of a geographic area. To say that organization is an autochthonous feature of what is experienced is to say that when experience is organized, it is primordially and originally organized. It means that “organization is inherent and immanent in immediate experience, and not brought about by any special organizing principle, agency, or activity.” (1992, p. 54).

To describe the inherent organization of the field of experience, Gurwitsch introduced the concept of “relevancy principles”. For a proper understanding of this central concept, it is necessary to first describe the domains Gurwitsch uses to characterize the field of consciousness. Gurwitsch followed James in claiming that every experience presents a focus that engrosses the mind of the perceiver, and a margin bound to the field for temporal reasons. Gurwitsch however introduces a further demarcation distinguishing the thematic field from the margin. The elements within the thematic field are functionally and materially relevant to the perspective from which the theme is perceived. Relevancy principles determine the interconnections of the elements within the thematic field and connect them with the theme. The elements within the thematic field are experienced as having affinity and “being of a certain concern to the theme”. They have something to do with it; they are relevant to it.“ (1964/2010, p.331).

Gurwitsch’s concept of the thematic field related to the focus by relevancy principles was partly inspired by the experiments of the Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler, conducted on chimpanzees in the Tenerife Islands (Köhler 1917/1925). Köhler showed that after a group of chimps learned how to use tools to reach food, the perceptual experience of the chimps underwent reorganization and regrouping. Based on these experiments, Gurwitsch argued that the objects directly given in experience have a functional character shaped by past experience. Over the course of development, the field of experience goes through a continuous process of reorganization based, in part, on experiences of acting in and with the environment.

“Before the very eyes of the experiencing subjects, the experiential stream itself undergoes a phenomenal transformation in that organization appears, whereas a moment previously it was altogether absent. Organization emerges out of the experiential stream and thus proves a feature imminent to and exhibited by immediate experience, not bestowed upon the latter from without.” (1964/2010, p. 32).

Gurwitsch describes the natural groupings as arising within the field of experience in virtue of how functional objects have been used in concrete situations, in connection with other tools in particular social settings. He gives the example of seeing an inkwell on a desk surrounded by pencils, papers and related implements. These surroundings represent what he describes as “the authentic milieu” of the inkwell. They reflect the typical setting in which we perform the activities of writing associated with the inkwell. When the inkwell is our theme, the other objects that occupy the thematic field are experienced as connected to it by a web of functional relationships that reflect the situations and activities in which the inkwell partakes in our society. The relevancy principles that underlie the theme-thematic field relationship reflect the person’s familiarity with these typical situations and the rules and maxims connected with them. However, the situation changes if the inkwell is moved to another context in which it is not generally used. If the inkwell is moved, for example, and placed on a piano, “It is displaced, “does not belong there”, is not found in its authentic milieu […] It looks differently, and its “function” changes with the thematic field” (Gurwitsch 1966, pp. 206–207.)

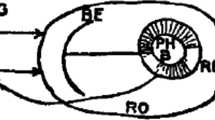

To conceive of the field of experience as structured only by the selective interests of the perceiver would result in an experience whose focus presents itself as “all shades and no boundaries” (Gurwitsch 1964/2010, p. 26). (See Fig. 1a.)

a: Fig. 1a represents the field of experience structured by the perceiver’s selective interest in the inkwell in its typical setting (left panel) and the same object displaced to the piano (right panel). The drawing aims to illustrate how James’ bipartite characterization of the field of experience leaves implicit how the social context may alter the experience of the inkwell. The difference between the focus and the fringes is depicted by the different contours, colouring and shading b: Fig. 1b represents the field of experience by making use of Gurwitsch’s distinction between theme, thematic field and margin. Unlike Fig. 1a, here it is possible to appreciate how the inkwell is differently experienced if moved from its typical setting (left panel) to a piano (right panel). We have suggested that if thought of as structured by socially established relevancy principles, the field of experience can be characterized in such a way as to make the existence of an intersubjective and socially organized paramount reality explicit. As in the previous figure, the difference between the theme thematic field and margin is depicted by the different contours, colouring and shading (Illustrations by Lorenzo Cantarella; our thanks for permission to publish them.)

Following Gurwitsch, we have argued that such a description of the structure of the field misses how experience has a theme that is related to a wider thematic field by relevancy principles. Distinguishing between the theme, thematic field and margin makes it possible to account for what Gurwitsch called the “autochthonous organization” of the field of experience (see Fig. 1b).

This difference in appearance requires making reference to the relevancy principles that organize experience. Such differences are not captured so long as we restrict our account to what the perceiver’s attention selects based on their momentary interests. If we assume the relationship between the inkwell and its surroundings is determined only by the perceiver’s selective interests, it becomes difficult to make sense of how context can qualitatively change the experience of the focus.

Many theorists in ecological psychology explain the development of perceptual skills in terms of the education of the child’s attention and intention by adults (e.g. Reed 1996; Gibson and Pick 2000; Jacobs and Michaels 2007). The child learns from their family and others in their community to pay attention to structure in flows of ambient information that is specific to affordances. Were it not for this educating of the child’s attention to structures within their ecological niche, the child might otherwise overlook or neglect affordances. The affordances the child selects as relevant is therefore in part due to shared attention to publicly and intersubjectively shared affordances.

A similar idea of attention as providing structure to the field of relevant affordances is outlined in de Haan and colleagues (2013). De Haan and colleagues describe the differences in structure of the field of relevant affordances of healthy individuals and that of subjects diagnosed with major depression or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The field of relevant affordances (see Fig. 2) is described as structured by three main dimensions represented by the coloured bars in the figure below. The width and height of each bar refers to the priority - the salience, importance - that is given to an individual affordance in relation to other relevant affordances. We can think of this in terms of the soliciting, inviting power or demand character of individual relevant affordances (Brown 1929; Koffka 1935; Lewin 1931; Dreyfus and Kelly 2007; Withagen 2022, 2023). The depth of the field as a whole signifies the temporal depth of the field and the subject’s anticipatory responses to the multiple affordances that solicit them in any given situation, some of which may lie in the future.

De Haan and colleagues suggest that the structure of the field depends upon the interests, needs and affective concern of the individual at the time. Thus, the concern of the person with OCD is shaped by their obsessions and compulsions. In OCD the field is dominated by affordances that relate to the person’s obsessions and compulsions, crowding out other relevant possibilities. The field of the person with major depression is by contrast characterized by a flatness. Due to their anhedonia, nothing in particular moves them to act. Their field is thus coloured grey in Fig. 32 below with a flatness that reflects the blunting of the depressed person’s emotions. The field of relevant affordances for the healthy individual is populated by multiple relevant affordances. The affordances that have the greatest soliciting power are a reflection of the person’s concern as a skilled agent to act in ways that are appropriate and adequate to their particular situation.

The field of relevant affordances in (a) healthy subjects as compared to individuals diagnosed with (b) Depression (c) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Reproduced with permission from de Haan et al. (2013). All copyrights are attributed to the original authors

It might be thought that the field of relevant affordances for the individual is structured by selective interests, just as was argued in James. However, a closer reading of SIF reveals this is not the case. The notion of skilled intentionality that is at the core of SIF is introduced to account for the individual’s selective and simultaneous responsiveness to multiple relevant affordances (Rietveld et al. 2018). The selection of relevant affordances from the affordances available in the local landscape is made on the basis of what Rietveld (2008; also see Van Den Herik and Rietveld 2021) called ‘situated normativity’. This is the capacity to make distinctions between better or worse, adequate or inadequate, correct or incorrect ways of acting in the context of a particular situation. Skilled individuals show an appreciation in a given situation for ways of acting that are appropriate to the particularities and uniqueness of the situation in which they find themselves. They are able to adequately adapt what they do to the unique and often unrepeatable features of the situation in which they are acting. The core idea behind skilled intentionality is that certain affordances stand out from the landscape and solicit action based on the individual’s sensitivity to situated norms.

This sensitivity is developed by participating in social and cultural practices.Footnote 10 Infants and young children for instance, under the guidance of their caregivers slowly become attuned to the norms, rules and maxims that tacitly structure everyday social interactions. They can learn, for example, how to use a spoon during lunchtime to eat soup, while responding to other affordances of the spoon during playtime in the garden, e.g., using the spoon to dig the ground (Heft 1982). The normative value of the spoon depends on its recurrent usages in a form of life and how these usages are realized within individual situations.Footnote 11

As Withagen et al. (2017) usefully note, one crucial aspect of inviting relevant affordances is that they can always be declined despite our needs, interest and plans. This is the case when some actions are not adequate or socially accepted by the pragmatics of the individual situation. Suppose for instance that I am a chain smoker. The solicitations offered by the pack of cigarettes in my pocket is mitigated by the fact that I am, at the moment, teaching and smoking is not allowed in the classroom. While our needs can make certain affordances strongly alluring, the socio-cultural contexts in which we typically act constrain us. They delimit what is appropriate or inappropriate in the light of the norms we follow by participating in communal practices (Wittgenstein 1953; Rietveld 2008).

We have seen above how Gurwitsch and Schutz recognized the structuring of everyday experience by our socio-cultural surroundings. with his distinction of the three domains invariantly present in all our experiences: the theme, the thematic field and the margin. These three domains can be thought of as structuring principles for the field of relevant affordances. The value of thinking of the field of relevant affordances through Gurwitsch’s tripartite model is the possibility of making explicit how each affordance is always selected and thematised as part of an intersubjective paramount reality.

6 Conclusion

Our paper has taken up questions relating to direct perception through a reflection on the reality of affordances - the possibilities for action provided to animals by the environment they inhabit. We have argued that affordances have a reality that is fundamentally experiential, and that is prior to any ontological separation of subjects from objects. Such an understanding of affordances as experiential in nature is well-captured by thinking of affordances in relational terms. Philosophers arguing for a relational account of affordances have tended to see selective engagement with affordances as something that can potentially explain lived experience (Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014; De Haan et al. 2013; Käufer and Chemero 2021; Rietveld et al. 2018). Many of them have, however, argued for an understanding of the reality of affordances as available to any animal that can perceive and act on them, and thus as independent from any particular experience of them. They have understood affordances from within the natural attitude, as belonging to a world whose continued and persisting existence we ordinarily take for granted.

We have traced the relational understanding of the affordance concept back to James’ radical empiricism. James sought to ground our metaphysical and scientific beliefs in an objective world in the facts of experience that are prior to any dichotomy of subjective experience and objective reality. He described how the world of experience is organized to suit our practical and emotional purposes and interests. What things are cannot be determined apart from the interests we have in such a determination. While agreeing with James, we have ended our paper by drawing upon the work of social phenomenology to propose an important correction. We have argued that affordances are best understood as belonging to fields of experience structured and organized not only by an individual’s personal interests, needs and purposes but also by their intersubjectively constituted, social and cultural life. This has led us to describe the experience of affordances as having a threefold structure made up of theme, a thematic field and a margin organized by socially and culturally established relevancy principles.

Notes

The term “pragmatic contact” is here employed to characterize perceptual capacities as aimed at securing “an unmediated contact with the environment” that is experienced as more or less useful by the perceiving animal (Van Dijk and Myin 2019: p.2). The notion of pragmatic contact is distinct from (but related to) what is sometimes called “epistemic contact”, a term used instead to characterize perceptual capacities as furnishing knowledge about the world (Turvey 2018: p.11). To analyse perceptual contact with the environment in epistemic terms requires thinking of perceptual capacities as assessable for truth or falsity, correctness or correctness, which is a defining feature of representational states that carry content. States that carry representational content are typically defined as states that are assessable for truth or falsity, accuracy or inaccuracy, or correctness or incorrectness. Thus, the epistemic understanding of perceptual contact runs the risk of contradicting the non-representational understanding of direct perception that is a key tenet of the ecological psychology research programme. For these reasons we will treat epistemic contact as a special case of pragmatic contact and describe direct perception in terms of pragmatic contact. Our thanks to an anonymous reviewer for inviting us to clarify this point.

The phenomenological implications of James’ work were noticed by Husserl (Geniusas 2012, ch.3; Moran 2018) and made explicit by social phenomenologists like Gurwitsch (1966, 1974) and Schutz (1966), who developed and integrated several of James’ ideas into their phenomenological writings. The main thesis of radical empiricism strongly aligns with the philosophical attitude underlying the phenomenological method. Cairns (1940) for instance describes “the fundamental methodological principle of phenomenology” in terms that echo James’ radical empiricism. He writes: “No opinion is to be accepted as philosophical knowledge unless it is seen to be adequately established by observation of what is seen as itself given “in person”. Any belief seen to be incompatible with what is seen to be itself given is to be rejected” (1940/1968, p. 4).

A notable exception is Harry Heft; in providing an intentional analysis of direct perception inspired by Merleau-Ponty (1945/2012), Heft (1989) defines what affordances are in relation to the body of a perceiving subject and its potentialities for action. He proposes to follow Merleau-Ponty in understanding the body of a perceiving animal as the “vehicle for its being in the world”. Heft’s intentional analysis of affordances is thus a clear precursor of the phenomenological view we develop in what follows (also see Heft 2001, ch.3; Heft 2003). Moreover, Heft is also concerned in this paper with providing an answer to the problem of how perception of the socio-cultural meaning of objects is possible (cf. Costall 1995; Heft 2007). Thus he comes close to defining what affordances are, as we will propose, in relation to lived intersubjective experience. It is noteworthy to mention that, more recently, some authors have begun to develop further possible characterizations of affordances in experiential terms. For example, Bogotá and Artese (2022) have provided a characterization of the affordance term based on the affective and temporal structure of phenomenological experience. Ludger van Dijk has instead developed an understanding of the shared environment in experiential terms, foregrounding in particular the indeterminacy and open-endedness of our experience of this environment, and questioning the tendency of ecological psychology to take for granted the ready-made existence of affordances (see e.g. Van Dijk 2021a,b).

We will follow interpreters of James such as Perry (1935), McDermott (1977), Seigfried (1990) and Heft (2017) in taking radical empiricist ideas to be prefigured in his early psychological writings. In particular, we take James’ notion of the field of experience, that is central in his early psychological writings, to be gradually substituted by the concept of pure experience.

The phenomenological reading of James has been developed by Perry (1935), Wilshire (1968), Edie (1987) Siegfried (1990) and more recently by Leary (2018) and Krueger (2022). These authors have pointed to James’ treatment of the concrete immediate and direct experience of relations. If conjunctive and disjunctive relations can manifest themselves as having different degrees of intimacy, it follows that experience must have a phenomenological structure necessary to make the experiences of these relations possible.

Interestingly, Schutz noticed that an important correlation with the phenomenological notions of noesis and noema could already be observed in some of James’s early concepts developed in the Principles. What Schutz had in mind were James’ dual notions of “thinking” and the “object of thought of” (1966b, p.30). While showing how these Jamesian concepts contained in germinal forms the motifs of radical empiricism goes beyond the scope of this paper, Schutz’s reflections highlight that the convergences between James’ work and the phenomenological tradition are far from being sporadic or coincidental.

Interpreters of Husserl have disagreed about how best to interpret his notion of the noema. Some have read the concept through the lens of Frege interpreting the noema as an ideal mode of presentation - a concept or proposition - that bestows meaning on individual noetic acts (see e.g. Follesdal 1969, McIntyre 1986, Dreyfus 1972). Consciousness is directed at the world only via an ideal intermediary on this reading. Others (e.g. Cairns 1940/1968; Drummond 1990, Zahavi 2004) have followed Gurwitsch (1966, 1964/2010) in understanding the noema as the perceived object just as it is perceived. It is this latter reading of the noema that is in keeping with James’ concept of pure experience, as we will explain further above.

In this article, we set aside important differences between Gurwitsch and Schutz. In their life-long correspondence, the two authors recognized that their respective approaches were reaching the same conclusions starting from different problems. After reading Schutz’s essay “On Multiple Realities” (1945), Gurwitsch described himself as “digging a tunnel” with Schutz producing “ knocking which announces the worker from the other side” (Grathoff 1989, p. 75).

A reviewer of this paper pointed out that James could have argued that what individuals attend to and are selectively interested in is pre-structured by individual’s taking part in social and cultural life. There is no obvious inconsistency between admitting that individual attention and selective interest structures experience from moment to moment and thinking of the field of experience as being always and already organized by social and cultural life. We agree and suggest that it is exactly this social and cultural pre-structuring of the field of experience that Gurwisch is pointing to when we claims that the organization of the field of experience is autochthonous. What we are questioning is that it is possible to account for the organization of the field of experience in isolation from the intersubjectively shared world in which experience typically takes place.

In a similar fashion, Maiese (2021) draws on Varela’s (1991) concept of micro-identities to argue that the agent’s interconnected skills, abilities and habits are related to the norms and social regularities of typical socio-cultural contexts. A field of relevant affordances will have a different organization if experienced from the perspective of a doctor, a schoolteacher, a family member or a dentist.

Baggs and Chemero (2019) also recognize that the structure of each individual’s umwelt depends in part on the individual’s social learning. They highlight that since our early days, we are immediately involved in ongoing social interactions with our caregivers who scaffold and guide our early activities. The normative character of the umwelt is always shaped by systemic cultural factors that go beyond individual needs and affective concerns (cf. Wilkinson and Chemero 2023).

References

Arvidson PS (1992) On the origin of organization in consciousness. J Br Soc Phenomenology 23:53–65

Baggs E (2021) All affordances are social: foundations of a Gibsonian social ontology. Ecol Psychol 33(3–4):257–278

Baggs E, Chemero A (2019) The third sense of environment. In: Wagman JB, Blau JJ (eds) Perception as information detection: reflections on Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Routledge, New York, pp 5–20

Baggs E, Chemero A (2021) Radical embodiment in two directions. Synthese 198(9):2175–2190

Bogotá JD, Artese GF (2022) A Husserlian Approach to Affectivity and Temporality in Affordance Perception. In: Djebbara Z (ed) Affordances in Everyday Life: a Multidisciplinary Collection of essays. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 181–190

Brown JF (1929) The methods of Kurt Lewin in the psychology of action and affection. Psychol Rev 36(3):200–221

Bruineberg J, Rietveld E (2014) Self-organization, free energy minimization, and optimal grip on a field of affordances. Front Hum Neurosci 195(6):2417–2444

Bruineberg J, Withagen R, van Dijk L (2023) Productive pluralism: the coming of age of ecological psychology. Psychol Rev. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000438

Cairns D (1940/1968) An approach to phenomenology. In: Faber M (ed) Philosophical essays in memory of Edmund Husserl. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 3–18

Chemero A (2003) An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecol Psychol 15(2):181–195

Chemero A (2009) Radical embodied Cognitive Science. MIT Press, Cambridge MA

Chemero A, Turvey MT (2007) Complexity, hypersets, and the ecological perspective on perception-action. Biol Theory 2(1):23–36

Cooper W (2002) The Unity of William James’s thought. Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, TN

Costall A (1995) Socializing affordances. Theory & Psychology 5(4):467–481

Costall A (2004) From Darwin to Watson (and cognitivism) and back again: the principle of animal-environment mutuality. Behav Philos, 179–195

de Haan S, Rietveld E, Stokhof M, Denys D (2013) The phenomenology of deep brain stimulation induced changes in OCD: an enactive affordance-based model. Front Hum Neurosci 7:1–14

Dennett DC (1998) Brainchildren. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass

Dewey J (1958) Experience and nature. Dover Publications, New York, NY

Dings R (2018) Understanding phenomenological differences in how affordances solicit action: an exploration. Phenomenology & the Cognitive Sciences 17:681–699

Dreyfus H (1972) The perceptual noema: Gurwitsch’s crucial contribution. In: Gurwitsch A, Embree LE (eds) Life-world and consciousness. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL, pp 135–139

Dreyfus H, Kelly SD (2007) Heterophenomenology: heavy-handed sleight of hand. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 6(1–2):45–55

Drummond J (1990) Husserlian Intentionality and Non-foundational Realism: Noema and object. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, NL

Edie JM (1987) William James and Phenomenology. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN

Follesdal D (1969) Husserl’s notion of the noema. J Philos 66(20):680–687

Geniusas S (2012) The origins of the Horizon in Husserl’s phenomenology. Springer, Dordrecht, NL

Gibson JJ (1979/2014) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Psychology Press, Hove, UK

Gibson EJ, Pick AD (2000) An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Goodman R (2017) William James. In N. Zalta (Ed) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (Winter 2017 Edition) https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/james/

Grathoff R (1989) Philosophers in Exile. The correspondence of Alfred Schutz and Aron Gurwitsch, 1939–1959. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN. (Trans. by J.C. Evans)

Gurwitsch A (1966) Studies in phenomenology and psychology. Northwestern University Press, Evanston

Gurwitsch A (1974) Phenomenology and Theory of Science. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL

Gurwitsch A (1964/2010) In: Zaner RM, Embree L (eds) The Collected Works of Aron Gurwitsch (volume III): the field of consciousness: theme, thematic field, and Margin. Springer, New York

Heft H (1982) Perceiving affordances in context: a reply to Chow. J Theory Social Behav 20(3):277–284

Heft H (1989) Affordances and the body: an intentional analysis of Gibson’s ecological approach to visual perception. J Theory Social Behav 19(1):1–30

Heft H (2001) Ecological psychology in Context: James Gibson, Roger Barker, and the legacy of William James’ Radical Empiricism. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Heft H (2003) Affordance, dynamic experience and the challenge of reification. Ecol Psychol 15(2):149–180

Heft H (2007) The social constitution of perceiver-environment reciprocity. Ecol Psychol 19(2):85–105

Heft H (2017) William James’ psychology, radical empiricism, and field theory: recent developments. Philosophical Inquiries 5:111–130

Heras-Escribano M (2019) The philosophy of Affordances. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK

Husserl E (1960) Cartesian meditations. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague. (Trans. by D. Cairns)

Husserl E (2001) Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Syntheses: Lectures on Transcendental Logic. (Trans. by D. Carr), Evanston, IL: Northwestern University

Husserl E (1989) Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy. Second Book. Studies in the Phenomenology of Constitution (Trans. by R. Rojcewicz & A. Schuwer), Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers

Jacobs DM, Michaels CF (2007) Direct learning. Ecol Psychol 19(4):321–349

James W (1890a) The principles of psychology, volume 1. Henry Holt and Company, New York, NY

James W (1890b) The principles of psychology, volume 2. Henry Holt & Company, New York, NY

James W (1912/1996) Essays in Radical Empiricism. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE

James W (1909/1975) The meaning of Truth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Käufer S, Chemero A (2021) Phenomenology: An Introduction. 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons

Koffka K (1935) Principles of Gestalt psychology. Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, NY

Köhler W (1917/1925) The mentality of apes. Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, NY. (Translated by E. Winter)

Krueger J (2022) James, nonduality, and the dynamics of pure experience. In: McBridge LA III, McKenna E (eds) Pragmatist Feminism and the work of Charlene Haddock Seigfried. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, UK, pp 193–216

Lamberth DC (1999) William James and the Metaphysics of experience. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Leary DE (2018) The Routledge Guidebook to James’s principles of psychology. Routledge Taylor Francis, New York

Lewin K (1931) The conflict between aristotelian and galileian modes of thought in contemporary psychology. J Gen Psychol 5(2):141–177

Maiese M (2021) An enactivist reconceptualization of the medical model. Philosophical Psychol 34(7):962–988

McDermott J (1977) Introduction. In: McDermott J (ed) The writings of William James. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

McIntyre R (1986) Husserl and the representationalist theory of mind. Topoi 5:101–113

Merleau-Ponty M (1945) /2012 Phenomenology of Perception. (Trans. by D. Landes) New York, NY: Routledge Taylor Francis

Moran D (2018) Phenomenology and Pragmatism: two interactions. From horizontal intentionality to practical coping. In: Baghramian M, Marchetti S (eds) Pragmatism and the European traditions: encounters with analytic philosophy and phenomenology before the great divide. Routledge, New York, NY, pp 269–287

Perry RB (1935) The Thought and Character of William James, vol. 2. Little, Brown, Boston, MA

Reed ES (1996) Encountering the World: toward an ecological psychology. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Rietveld E (2008) Situated normativity: the normative aspect of embodied cognition in unreflective action. Mind 117(468):973–1001

Rietveld E, Kiverstein J (2014) A rich landscape of affordances. Ecol Psychol 26(4):325–352

Rietveld E, Denys D, Van Westen M (2018) Ecological-enactive cognition as engaging with a field of relevant affordances: The skilled intentionality framework (SIF). In: A. Newen, L. De Bruin, & S. Gallagher (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, Oxford University Press, pp. 41–70

Schutz A (1945) On multiple realities. Philos Phenomenol Res 5:533–575

Schutz A (1966) William James’s concept of the stream of thought phenomenologically interpreted’. In: Schutz I (ed) Collected papers III: studies in Phenomenological Philosophy. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, pp 1–14

Seigfried CH (1976) The structure of experience for William James. Trans Charles S Peirce Soc 12(4):330–347

Seigfried CH (1990) William James’s Radical Reconstruction of Philosophy. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

Stoffregen TA (2003) Affordances as properties of the animal-environment system. Ecol Psychol 15(2):115–134

Turvey MT (1992) Affordances and prospective control: an outline of the ontology. Ecol Psychol 4(3):173–187

Turvey MT (2018) Lectures on perception: an ecological perspective. Routledge Taylor Francis, New York, NY

Van den Herik JC (2021) Rules as resources: an ecological-enactive perspective on linguistic normativity. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 20(1):93–116

Van den Herik JC, Rietveld E (2021) Reflective situated normativity. Philos Stud 178(10):3371–3389

Van Dijk L (2021a) Psychology in an indeterminate world. Perspect Psychol Sci 16(3):577–589

Van Dijk L (2021b) Affordances in a multispecies entanglement. Ecol Psychol 332:73–89

Van Dijk L, Myin E (2019) Reasons for Pragmatism: affording epistemic contact in a shared environment. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 18:973–997

Van Dijk L, Rietveld E (2017) Foregrounding sociomaterial practice in our understanding of affordances: the skilled intentionality framework. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01969

Varela FJ (1991) Organism: a meshwork of selfless selves. In: Tauber A (ed) Organism and the origins of Self. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, pp 79–107

Wilkinson T, Chemero A (2023), forthcoming Why it matters that affordances are relations, Preprint part of the manuscript: Affordances and its entailment in organisms and autonomous systems”. In M. Mangalam, A. Hajnal, & D.G. Kelty-Stephen (eds.) The Modern Legacy of Gibson’s Concept of Affordances for the Science of Organisms New York, NY: Routledge Taylor Francis

Wilshire B (1968) Willian James and Phenomenology: a study of the principles of psychology. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Withagen R (2022) Affective Gibsonian psychology. Routledge Taylor Francis, New York, NY

Withagen R (2023) The field of invitations. Ecol Psychol 35(3):102–115

Withagen R, De Poel HJ, Araújo D, Pepping GJ (2012) Affordances can invite behavior: reconsidering the relationship between affordances and agency. New Ideas Psychol 30(2):250–258

Withagen R, Araújo D, de Poel HJ (2017) Inviting affordances and agency. New Ideas Psychol 45:11–18

Wittgenstein L (1953) Philosophical investigations. Blackwell, Oxford UK

Zahavi D (2004) Husserl’s noema and the internalism-externalism debate. Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy 47(1):42–66

Acknowledgements

Julian Kiverstein is supported by a Vici grant from the Netherlands Scientific Organisation (awarded to Erik Rietveld).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiverstein, J., Artese, G.F. The Experience of Affordances in an Intersubjective World. Topoi 43, 187–200 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-023-09969-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-023-09969-4