Abstract

In this paper I argue for a non-referential interpretation of some uses of indexicals embedded under epistemic modals. The so-called descriptive uses of indexicals come in several types and it is argued that those embedded within the scope of modal operators do not require non-referential interpretation, provided the modality is interpreted as epistemic. I endeavor to show that even if we allow an epistemic interpretation of modalities, the resulting interpretation will still be inadequate as long as we retain a referential interpretation of indexicals. I then propose an analysis of descriptive indexicals that combines an epistemic interpretation of modality with a non-referential interpretation of indexicals.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Descriptive Uses of Indexicals

Descriptive uses of indexicalsFootnote 1 are uses where indexical utterances express general propositions (see Nunberg 1993, 2004; Recanati 1993, 2005; Bezuidenhout 1997; Elbourne 2005, 2008; Hunter 2010; Stokke 2010; Galery 2008; Kijania-Placek 2012a). An example, given by Nunberg (1992) and, in this version, by Recanati (2005), is the following utterance:

- (1):

-

He is usually an Italian, but this time they thought it wise to elect a Pole

[uttered by someone gesturing towards John Paul II as he delivers a speech with a Polish accent shortly after his election]

In this example one expresses not a singular proposition about John Paul II, but a general one, concerning all popes. Because ‘usually’ is a quantifier that requires a range of values to quantify over, and because ‘he’ in its standard interpretation provides just one object, there is a tension in this sentence which triggers the search for an alternative interpretation. The tension is not caused by the fact that John Paul II himself is the possible referent but it is a tension between the generality of the quantifier and the singularity of the indexical in its default interpretation. The tension would be there regardless of who the referent was. Intuitively we know that with the use of the pronoun ‘he’ we point at John Paul II and by doing so we make his property of being the pope more salient.Footnote 2 It is this property that plays a role in the truth conditions of the proposition expressed, which is ‘Most popes are Italian’. In Sect. 5 I will propose an analysis of the special kind of contribution of the property retrieved from the context to the proposition that is characteristic of a descriptive interpretation of an indexical and explain the relation of my proposal to other forms of non-presumptive meaning (Levinson 2000).

Sometimes, however, a descriptive interpretation is triggered not by a tension between the singularity of the indexical and the generality of the quantifier, but by the blatant irrelevance of the referential interpretation—its incompatibility with a salient goal of the utterance or its obvious triviality or falsity. This occurs when the singular proposition that would be expressed if the indexical was interpreted referentially comes in conflict with the pragmatic purpose of expressing it, such as warning or critique. It is then this conflict that triggers a descriptive interpretation.Footnote 3 In typical cases of this type, the indexical is embedded under modal operators (Hunter 2010). An interesting example was again given by Nunberg and is drawn from Peter Weir’s movie ‘The Year of Living Dangerously’. Mel Gibson plays a reporter in Indonesia, Mr. Hamilton, who is investigating arms shipments for local communists and, of course, he would be in trouble if they found out. Hamilton, talking to a warehouse manager and inquiring after the shipments, receives a warning:

-

– MR. HAMILTON?

-

BE CAREFUL WHO YOU TALK TO ABOUT THIS MATTER.

-

I’M NOT P.K.I., BUT I MIGHT HAVE BEEN. Footnote 4

Following Nunberg (1991), I paraphrase the last sentence as:

- (2):

-

I might have been a communist

The interlocutor explicitly says that he is not a communist, he is thus not warning Hamilton against himself. Initially, it is thus at least unlikely that the semantic value of the indexical in this utterance is the speaker himself, which would be the case if the indexical was interpreted referentially. In what follows, I will concentrate on the analysis of (2), starting from the metaphysical interpretation of the modality.

2 Metaphysical Interpretation of Modality

Utterance (2) is semantically consistent under the referential interpretation of the indexical and the metaphysical interpretation of the modality. Interpreted thus, it would express a modal proposition in this context, containing a singular proposition about the utterer of the sentence in its scope. Such a proposition is true if and only if that very person is a communist in some counterfactual situation. Yet that proposition is impotent as a warning: for Hamilton’s safety here, it is totally irrelevant who his current interlocutor is in a counterfactual situation, as long as he is not a communist in the actual situation. Somebody must be a communist in this world to put Hamilton in danger. For what has been uttered to work as a warning, we cannot interpret the modality as concerning the speaker’s properties in some other, counterfactual situation.

Accepting this kind of argument, Recanati (1993, p. 306) claims, however, that interpreting the modality as epistemic would allow us to retain the referential interpretation of ‘I’ in (2). This would be important, because admitting the need of a descriptive, i.e. general, interpretation of indexicals in some modal context threatens his thesis of the type-referentiality of indexicals. Even though I will try to show below that Recanati’s claim cannot be sustained, I think his proposal of the epistemic interpretation of the modal in (2) is intuitively correct and I will follow his suggestion below. This intuitive character of the epistemic interpretation of the modal is probably the reason why Recanati, as well as MacFarlane (p.c.), assume, without further argument, that the epistemic interpretation of the modal solves the problem of ‘alleged’ non-referential readings of some indexicals in modal contexts.

Because in example (2) we are concerned with modality in the subjunctive mode, however, the interpretation of the modality as epistemic is not straightforward. In Sect. 3 I will introduce extant interpretations of epistemic modality and show why most of them are inappropriate for the case analyzed. In Sect. 4 I will show why the one remaining epistemic interpretation of modality that is suitable for (2) still gives an inadequate reading of the whole utterance as long as we retain the referential reading of the indexical. I will then propose (Sect. 5) an analysis of example (2) that combines an epistemic interpretation of the modal with a descriptive interpretation of the indexical ‘I’, and which gives the intuitive reading of (2).

3 Epistemic Modality

The epistemic interpretation of modality is concerned with the knowledge of the speaker or hearer about the world he lives in. This knowledge is usually represented by the set of epistemically possible worlds, i.e. such worlds about which it is not excluded by what the speaker (or hearer) knows that they are the real world. As Lewis put it:

“The content of someone’s knowledge of the world is given by his class of epistemically accessible worlds. These are the worlds that might, for all he knows, be his world; world W is one of them iff he knows nothing, either explicitly or implicitly, to rule out the hypothesis that W is the world where he lives. […] Whatever is true at some epistemically […] accessible world is epistemically […] possible for him. It might be true, for all he knows […]. He does not know […] it to be false. Whatever is true throughout the epistemically […] accessible worlds is epistemically […] necessary; which is to say that he knows […] it, perhaps explicitly or perhaps only implicitly.” (Lewis 1986, p. 27)

Thus, according to the epistemic interpretation of modality, an utterance such as “φ might be the case” is true if and only if the truth of φ is not excluded by what the speaker (or hearer) knows in the moment of the utterance (DeRose 1991; von Fintel and Gillies 2008, 2011; MacFarlane 2011 or Kment 2012). In effect, the modality is relativized to the knowledge of a person or a group relevant in a context; usually it is relativized to the speaker. This relativisation is typically represented by an information base, also called a modal base (MB):

Definition 1 (epistemic possibility I) [von Fintel and Gillies 2008]

MightMB φ is true in w iff φ is true in some world that is MB-accessible from w

MB represents the relevant state of knowledge and MB-accessibility means consistence with this knowledge, so MB–accessibility is a kind of accessibility function between possible worlds. Thus, when I utter the sentence ‘Peter might still be at home’ I do not express the trivial proposition to the effect that there exists a metaphysically possible world in which Peter is now still at home, which is always true as far as contingent facts are concerned. I rather express a proposition comprising epistemic possibility: ‘From what I know it is not excluded that Peter is still at home’. So it might seem that the basic difference between metaphysical and epistemic modality is that when we know that φ is true, ‘Might ¬φ’ may only be interpreted metaphysically (as true); i.e. our knowledge that φ entails the falsity of ‘Might ¬φ’, if the modality is interpreted as epistemic.Footnote 5

We should remember, however, that epistemic modality is relativized to the relevant state of knowledge and this does not always have to be the knowledge of the speaker—it may be the knowledge of the speaker or the hearer, or of both of them considered as a group (see DeRose 1991; MacFarlane 2011; von Fintel and Gillies 2011; Kijania-Placek 2012a). This intuitive difference between epistemic and metaphysical modality might thus require refinement. But in any case, the epistemic possibility must be consistent with some such knowledge state.

The definition of epistemic possibility formulated above (Definition 1) is, however, not directly applicable to example (2), because the sentence is not in the indicative (‘I might be a communist’) but in the subjunctive mode (‘I might have been a communist’). DeRose (1991) warns us against interpreting possibility in the subjunctive mode as epistemic, but already Hacking (1967) had argued against a simple identification of the subjunctive mode with metaphysical modality. von Fintel and Gillies (2008, p. 34) give compelling examples of epistemic modality in the subjunctive mode:

- (3):

-

There must have been a power outage overnight

- (4):

-

There might have been a power outage overnight

If the modality in (3) were to be interpreted metaphysically, we would attribute metaphysical necessity to this event, while we rather claim that for what we know it looks like there was a power outage overnight (or: the evidence shows conclusively that there have been a power outage overnight).

Modal sentences in subjunctive mode are thus ambiguous and the ambiguity may be considered as the structural ambiguity of scope between the modal operator and the past tense operator. I will use Condoravdi’s example to illustrate this ambiguity:

- “(5):

-

He might have won the game

- (6a):

-

He might have (already) won the game. [#but he didn’t]

- (6b):

-

At that point he might (still) have won the game but he didn’t in the end.

In the epistemic reading, the possibility is from the perspective of the present about the past […]. The modality is epistemic: (6a) is used to communicate that we may now be located in a world whose past includes an event of his winning the game. The possibility is in view of the epistemic state of the speaker: his having won the game is consistent with the information available to the speaker. The issue of whether he won or not is actually settled, but the speaker does not […] know which way it was settled. The counterfactual reading involves a future possibility in the past and the modality is metaphysical. (6b) is used to communicate that we are now located in a world whose past included the (unactualized) possibility of his winning the game.” (Condoravdi 2002, p. 62).

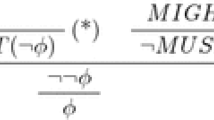

According to Condoravdi, the epistemic modality always takes a wide scope with respect to the operator of the past. The truth conditions of (5), with modality interpreted as epistemic, can thus be defined according to the following schema:

Definition 2 (epistemic modality II) [Condoravdi 2002, p. 61]

Might-have epistMB φ is true in 〈w, t〉 iff there exist w′, t′ such that w′ ∈ MB (w, t), t′ ≺ t and φ is true in 〈w′, t′〉.

Thus, according to Definition 2, we consider here the possibility about the past, from the point of view of the moment of utterance, because it is the knowledge state from the moment of utterance that is relevant, not the knowledge state form the past: ‘According to what we know now, he might have won the game’.Footnote 6

The metaphysical interpretation of possibility, on the other hand, may be defined thus:

Definition 3 (metaphysical modality) [Condoravdi 2002, p. 63]

Might-have metMB φ is true in 〈w, t〉 iff there exist w′, t′, t″ such that t′ ≺ t, w′ ∈ MB (w, t′), t′ ≺ t″ and φ is true in 〈w′, t″〉.

Here we consider what has been true in the past and this is represented by the relativisation of the possibility to the state of knowledge at a moment in the past and not at the moment of utterance. According to Condoravdi, epistemic modality always scopes over the past operator: it is now possible, i.e. not excluded by what we now know, that it has been the case that φ.

Under the assumption of the mandatory wide scope of the modal operator, Fernando (2005) claims that the epistemic interpretation excludes the sustainability of the modal claim if we know that the embedded sentence is not true. So, although ‘John might have won’ may be interpreted as an epistemic possibility, ‘John did not win but he might have won’ allows only a metaphysical interpretation: ‘He might have won, had he listened to my advice. It was within his reach up to some point in time’. This particular example about John is quite convincing and seems to undermine the feasibility of the epistemic interpretation of the possibility in (2). After all, since the Indonesian claims that he is not a communist, his next utterance should not be interpreted as a claim of ignorance. We should remember though, that the inconsistency of claiming that ¬φ followed by ‘It might have been that φ’, where the modal is interpreted as epistemic, is based on the assumption that the knowledge state is relativized to the moment of utterance (the wide scope assumption). After the speaker said that he is not a communist, both the speaker and the hearer know that he is not a communist.

Condoravdi’s thesis (assumed by others as well)—that epistemic modality always takes the wide scope with respect to the operator of the past—has been challenged by von Fintel and Gillies (2008, p. 43), with the help of the following example:

- (7):

-

The keys might have been in the drawer

The authors do not give a detailed analysis of this example but claim that here the modality is in the scope of the tense operator. Portner proposes interpreting this case in the following way:

“This sentence has a meaning close to “Based on the evidence that I had in the past, it was possible that the keys were in the drawer.” (It also has a meaning with the expected scope, “Based on the evidence I have now, it is possible that the keys were in the drawer.”)” (Portner 2009, p. 169).

As I may now know something I did not know before, it is clear that these two interpretations give different truth-conditions. It is less clear, however, what are the circumstances that would make the first interpretation more salient. The situation changes if instead of considering the knowledge of the speaker, as Portner does, we concentrate on the knowledge of the hearer. Imagine John and Paul quarreling about who is responsible for losing the keys they have been trying to locate for the last few days. Assume it is Paul who gave away for scrap a metal desk without first checking what was in its drawers. John, irritated, might say:

- (8):

-

Many valuable things might have been there. The keys might have been in the drawer. You should have checked

A natural reading of this utterance is based on their mutual knowledge at the moment of utterance: ‘From what we know it is not excluded that the keys were in the drawer’. But assume that the keys are found. Still, it seems that John may sustain his claim:

- (8a):

-

Anyhow, the keys might have been in the drawer. You should have checked

Now we cannot assume that the possibility is relativized to their knowledge from the moment of utterance, because “Based on the evidence I have now, it is possible that the keys were in the drawer” is incompatible with the fact that the keys are found, so they both now know that the keys haven’t been in the drawer. Yet, John’s utterance may be interpreted as a reproach: ‘The keys weren’t in the drawer. But you didn’t know it, so you should have checked’. This interpretation requires, however, a clear reference to the knowledge of the hearer at a moment in the past, so the possibility is indeed in the scope of the operator of the past tense. And this interpretation of epistemic modality is not excluded by the fact that we now know that something is not the case. Thus the alleged difference between the metaphysical and epistemic possibility—that when we know that φ is true, ‘Might ¬φ’ may only be interpreted metaphysically—turns out not to be sustainable.

4 Descriptive Indexicals in the Scope of Epistemic Modals

For the analysis of the initial example about Hamilton, repeated here in a slightly different version, this last interpretation—with the possibility operator in the scope of the tense operator—seems to be the relevant one:

- (2a):

-

I am not a communist. But I might have been

The epistemic interpretation of possibility with reference to the moment of utterance is excluded by the speaker’s declaration in the first sentence—we know now that he is not a communist, so his being a communist is not compatible with the present state of knowledge. But it is compatible with taking the state of knowledge of the addressee from the time before the utterance of (2a) as the modal base. This new interpretation would be something like ‘I am not a communist, you were lucky. But for all you knew before, it was not excluded that I am’.

With this last interpretation we are close to what we need but we are not there yet—this is only a reproach about past reckless behavior, while Hamilton received a warning:

- (2b):

-

Be careful who you talk to about this matter. I’m not P.K.I., but I might have been

(2b) is not just a statement about a past reckless behavior—which was not correct but does not really matter because Hamilton was lucky—but a future-directed warning, about similar situations, which might not concern the speaker, so his not being a communist is not inconsistent with them. As long as we retain the referential reading of the indexical, the sense of the warning is given by neither an epistemic nor a metaphysical interpretation of modality, as they both concern the speaker himself, who is not a communist, while the warning concerns Hamilton’s other interlocutors, who are relevantly similar to the present speaker. If the warning concerned the speaker, it should be cancelled by the declaration that he is not a communist, but in fact it is not cancelled and even emphatically strengthened by this declaration. Thus regardless of whether we interpret the modality epistemically or metaphysically, we do not get the sense of the general warning as long as we retain the directly referential interpretation of the indexical ‘I’ in (2).

Additionally, there are examples of the descriptive uses of indexicals, in which the sense of the utterance is not a warning but a reproach, and in which even relativisation of the possibility to the knowledge state of the hearer in the past does not yield adequate interpretation as long as we retain the referential reading of the indexical. To illustrate, I will consider Borg’s example, which is based on examples by Recanati (1993) and Nunberg (1993):

- “(9):

-

You shouldn’t have done that, she might have been a dangerous criminal.

said to the child who has just let her sweet, grey-haired grandmother in, but without checking first to see who it was”. (Borg 2002, p. 14).

In this case, even reference to the child’s knowledge at the time before opening the door would not make an epistemic interpretation of the modal tenable as long as we retain the referential reading of ‘she’ in (9), because the child always knew that the grandmother was not a criminal (we assume that she was not). Thus the epistemic interpretation of the modal gives absurd results regardless of whose knowledge and at what time is taken into account if the knowledge concerns the grandmother herself. And a metaphysical interpretation of the modal fares no better as it gives either a trivial or a manifestly false (if we exclude the world in which the grandmother is a criminal from accessible worlds) proposition. The intended proposition expressed by (9) is a general one, concerning whoever is at the door.

What is required is a mechanism that would combine the epistemic interpretation of modals for cases such as (2) and (9) with non-referential interpretation of the indexicals. In what follows I will propose such an interpretation.

5 Descriptive Anaphora

5.1 The Mechanism of Descriptive Anaphora

I propose treating descriptive uses of indexicals as a special kind of anaphoric use which I call descriptive. In the mechanism of descriptive anaphora, the antecedent of the anaphora stems from the extra-linguistic context: it is an object identified through the linguistic meaning of the pronoun (in the case of pure indexicals) or by demonstration (for demonstratives). In a communication context, those objects serve as a means of expressing content and, as such, they acquire semantic properties.Footnote 7 The antecedent is used as a pointer to a property corresponding to it in a contextually salient manner and that property contributes to the general proposition expressed. The context must be very specific in order to supply just one such property, which explains why there are not many convincing examples of the felicitous use of descriptive indexicals. The structure of the general proposition is determined by a binary quantifier, usually the very quantifier that triggered the mechanism of descriptive anaphora in the first place. The anaphora is descriptive in the sense that the antecedent does not provide a referent for the pronoun. It gives a property which is not a referent—the property retrieved from the context serves as a context set that limits the domain of the quantification of the quantifier (see Kijania-Placek 2012a, b, 2014, 2015 and (under review)).

My proposal should be seen as falling within the field of truth-conditional pragmatics, i.e. theories that allow that “pragmatics and semantics […] mix in fixing truth-conditional content” (Recanati 2010, p. 3) of the proposition expressed and according to which pragmatic contribution is not limited to providing values to indexical elements of a sentence (Jaszczolt 1999; Recanati 2004, 2010; Sperber and Wilson 1986, 2004; Carston 2002; Levinson 2000; Kamp 1981; Heim 1988; Magnano and Capone 2015). At the same time, I consider the descriptive interpretation of indexicals to be cases of non-presumptive meaning (Levinson 2000) and interpretations of not types but tokens of expressions. That is because I consider the descriptive use of an indexical not to be its basic use. The descriptive interpretation process is triggered exactly by the semantic inadequacy of its basic (presumptive, preferred) uses: deictic, (classically) anaphoric, or deferred.Footnote 8 Typically, descriptive anaphora is triggered at the level of linguistic meaning by the use of quantifying words such as ‘traditionally’, ‘always’, or ‘usually’, whose linguistic meanings clash with the singularity of the default referential reading of indexicals (and those quantifiers need not be overt). As a result, the pronoun’s basic referential function is suppressed.

Treating descriptive interpretation of indexicals as cases of non-presumptive meaning does not automatically mean, however, that they should be treated on a par with implicatures or metaphorical meaning. Rather, paraphrasing an argument of Levinson, from the fact that in language after language all five functions, i.e. bound, anaphoric, deictic, deferred and descriptive, can be performed by the same pronominal expressions suggests that their semantic character simply encompasses all five (Levinson 2000, pp. 269–270).Footnote 9 In effect, I propose that indexicals considered as a semantical type are semantically undetermined, allowing for bound, anaphoric, deictic, deferred and descriptive uses. And while descriptive interpretation is non-basic and parasitic on failures of the remaining interpretations, none of the basic interpretations is the singularly default one (see Jaszczolt 1999 for an opposing view). I will return to the consequences of this view for the semantics of indexicals at the end of this paper.

I will exemplify the mechanism of descriptive anaphora with the help of example (1),

- (1):

-

He is usually an Italian

In (1) the linguistic meaning of ‘he’ requires reference to one particular person but ‘usually’ is a quantifier that here quantifies over a set of people (but see below for a qualification). This tension triggers a search for an alternative interpretation via descriptive anaphora, with John Paul II as the demonstrated antecedent. I repeat that John Paul II is not the semantic value for ‘he’ as no antecedent is ever a value for the anaphora—it gives the value. The salient property of John Paul II—‘being a pope’—is the semantic value of ‘he’. ‘usually’ is a binary quantifier—usually x (φ(x), ψ(x))—analyzed according to the generalized quantifiers theory (e.g. Barwise and Cooper 1981).Footnote 10 The structure of the proposition is thus as follows:

-

usually x (pope(x), Italian(x)),

and usually has the truth conditions of the majority quantifier:

Mgi ⊨ usually x (φ(x), ψ(x)) iff |φMgi ∩ ψMgi| > |φMgi \ ψMgi|Footnote 11

where g is an assignment and i is a context. Such an analysis gives the intuitive reading for (1): ‘Most popes are Italian’.Footnote 12 In general, the structure of the interpretation can be given by the following schema:

-

IND is Qψ ⇒ Qx(φ(x), ψ(x)),

where IND is an indexical, Q is a quantifier, φ is the property corresponding to the object which is the antecedent of IND and ⇒ should be read as ‘expresses the proposition’.

In typical cases, descriptive anaphora is triggered by the use of adverbs of quantification in contexts in which they quantify over the same kind of entities that the indexicals refer to.Footnote 13 In such contexts the generality of the quantifiers clashes with the singularity of the default referential reading of indexicals. Whether there is a clash is, however, a pragmatic matter, as it depends on the domain of quantification of the quantifier, which for most adverbs of quantification is not given as part of the semantics of the word (compare Lewis 1975). If ‘usually’ quantified over periods of time or events—like in ‘He is usually calm’Footnote 14—there would be no conflict between ‘usually’ and ‘he’. Since in the case of descriptive uses of indexicals of this type it is the conflict between the generality of the quantifier and the singularity of the indexical which results in suppressing the referential reading of the indexical, both linguistic and extralinguistic context play a role here. The domain of quantification is dependent mainly on what is predicated of the objects quantified over (linguistic context) but in some cases it relies as well on such extra-linguistic features of context as world knowledge (see Kijania-Placek 2015). For example in (2)—in contrast to ‘He is usually calm’—a (relatively) static property is attributed to the subject, a property which typically does not change with time, but changes from person to person. And it is the attribution of this property that is a decisive factor in determining the domain of people as the domain of quantification in (2), leading to the descriptive interpretation of ‘he’. For the descriptive interpretation to be triggered, the predication must be non-accidental, in Aristotle’s sense, where “[a]n accident is something which […] belongs to the subject [but] can possibly belong and not belong to one and the same thing, whatever it may be” (Topics 102b5ff, Aristotle 2003). If a property is in this sense accidental, nothing prevents the hearer from considering different events or times at which it may be attributed to the same subject, leaving the possibility of a referential interpretation of the indexical uncompromised and thus not triggering the descriptive interpretation. At the same time, the property does not have to be an essential property of the relevant object, if by essential we mean a property that is metaphysically necessary. For example ‘being born in Italy’ is a non-accidental property that cannot be both attributed and denied of the same person, but, arguably, is not a necessary property. Still the use of ‘being born in Italy’ will trigger a descriptive interpretation of ‘he’ in ‘He is usually born in Italy’ in a context similar to that assumed for (1).Footnote 15

5.2 Descriptive Indexicals in the Scope of Epistemic Modals

We are now ready to propose an analysis of example (2):

- (2):

-

I might have been a communist

The mechanism of descriptive anaphora is triggered in this case by the inadequacy (irrelevance) of an interpretation that would retain the referential reading of the indexical ‘I’. But the mechanism stays the same as in the analysis of example (1): we search the context for a property of the speaker, who is the extra-linguistic antecedent for ‘I’. The aim of the utterance—a warning—excludes properties uniquely identifying this person in the actual world, because he said that he himself is not a communist. In this case his salient property is ‘warehouse manager’. This property serves the purpose of the context set for the binary existential quantifier which is implicit in this type of modal construction:

-

might-have epist exists x(warehouse-manager(x), communist(x)),

where the truth conditions for the existential quantifier are the following:

-

Mgi ⊨ exists x(φ(x), ψ(x)) iff |φMgi ∩ ψMgi| ≠ ∅.

might-have epist is an epistemic possibility relativized to the past (prior to the utterance) knowledge of the addressee: ‘From what you knew before, it was nor excluded that there are warehouse managers who are communists’ (or ‘warehouse managers whom you meet in Indonesia who are communists’). Under the referential interpretation this modal base was the only conceivable (but still unsatisfactory) interpretation. But when we consider the descriptive interpretation of the indexical, a more natural move as far as the warning is concerned is to relativize the modality to the actual knowledge of the speaker, knowledge he shares with Hamilton by warning him: ‘From all I know, it is not excluded that there were (and are) warehouse managers in Indonesia who are communists.’ It is only the last interpretation that gives the content and force of the warning in this dramatic scene from ‘The year of living dangerously’.

In a similar vein, the epistemic interpretation of modality, together with the mechanism of descriptive anaphora, give the relevant interpretation of (9):

- (9):

-

She might have been a dangerous criminal

As before, we search the context for a salient property of the grandmother, who is the demonstrated antecedent of ‘she’. In this case the salient property is ‘being the person who rung the bell’. The quantifier which gives the structure of the general proposition embedded under the modal operator is here the covert definite description quantifier.Footnote 16 As a result we obtain the proposition:

-

might-have epist the x(rings-the-bell(x), criminal(x)),

where the truth conditions for the definite description quantifier are the expected ones:

-

Mgi ⊨ the x(φ(x), ψ(x)) iff |φMgi| = 1 and φMgi ⊆ ψMgi,

and might-have epist is the epistemic modality relativized to the relevant in this context information base, i.e. the knowledge of the child at the moment of opening the door. We thus get: ‘Your knowledge at the moment of opening the door did not exclude it that the person who rung the bell was a dangerous criminal’.Footnote 17

6 Conclusion

I have tried to show first that the recourse to an epistemic interpretation of modals is not sufficient to sustain a referential interpretation of indexicals embedded under modal operators in some contexts. If this claim is correct, Recanati’s (1993) thesis about the type-referentiality of indexicals requires amendment.Footnote 18 It looks like indexicals are referential in some types of uses—deictic, (classically) anaphoric or deferred—while they are not referential in descriptive uses. Such a piecemeal analysis seems to be in the spirit of Kaplan (1989), who proposed a referential interpretation just for one type—deictic—of uses of indexicals. Additionally, the cases I have considered can be treated as counterexamples to the thesis of the necessary wide scope of modal operators interpreted epistemically.

Notes

Even though personal pronouns are usually used to refer to individuals already salient in the context and demonstratives such as ‘this’, ‘that’ or ‘that man’ are used for new objects (see Jaszczolt 1999), in both cases the property retrieved from the context must be salient—be it perceptually salient or salient in terms of the focus of the discussion—prior to the utterance in order for the descriptive interpretation to succeed. See Sect. 5.1 below.

Relevance plays a role in all types of descriptive uses of indexicals (see footnote 13), but its role as the trigger of the descriptive interpretation becomes prominent when the referential interpretation is consistent. In such cases, consideration of the type of the speech act, the purpose of the utterance and possible conflicts with other pragmatic presumptions (Macagno and Capone 2015) may induce the search for an alternative interpretation. Since the referential interpretation is consistent and fully propositional, a natural move might be to propose an analysis of such examples in terms of Grice’s particularized implicatures (see Stokke 2010; Grice 1989). I have argued against such an analysis in Kijania-Placek (2012a). Here allow me to highlight the fact that the descriptive interpretation may be retained under embeddings and in elliptic constructions, which is a phenomenon difficult to reconcile with treating such cases as implicatures. Additionally, examples such as (9) below would require attributing inconsistent beliefs to interlocutors (see Sect. 5.2 below), which, I think, makes them non-starters for the calculation of an implicature. Such an understanding of relevance considerations is in line with the work of Sperber and Wilson (1986, 2004) and Carston (2002), who insist on the role relevance plays is the reconstruction of the explicature. I do not place my proposal in the framework of relevance theory as such, because I wish to remain neutral as to the special cognitive commitments of this theory (such as the modularity of mind or the thesis that it is mental representations that refer to objects in the first place and words refer only indirectly). If a reader wants, however, to consider the proposal presented in Sect. 5 from within that theory, it should be seen as a detailed elaboration on the mechanisms that govern the interpretation of indexicals, and potentially other singular terms such as proper names [for a proposal of an analysis of proper names in proverbs via the mechanism of descriptive anaphora see Kijania-Placek (in preparation)].

‘P.K.I.’ is an abbreviation for ‘Partai Komunis Indonesia’.

Hacking and DeRose seem to treat it as a necessary condition of an epistemic interpretation of modality that the speaker does not know otherwise: “Whenever a speaker S does or can truly assert, “It’s possible that P is false,” S does not know that P” (DeRose 1991, p. 596). Compare Hacking (1967, pp. 149, 153).

An anonymous referee suggested that apart from considering the moment of utterance we should take into account the location of utterance as well: something may be possible from the perspective of here (where the river looks small), but not there (where the river looks large and unnavigable). But I think that since we relativize the knowledge base both to the relevant agent(s) and to time, that should automatically account for the place the agent(s) is(are) at that time without additional provisions, at least for the cases considered. It might transpire, however, that such an addition might be necessary in a fully general definition of epistemic possibility.

Deferred use of an indexical is when, for example, you use a personal pronoun while pointing at a photograph to talk about a person depicted in the photograph. Such uses were first distinguished by Nunberg (1978, 1993). The important difference between deferred and descriptive uses of indexicals is that in the former the proposition expressed by the utterance is still singular, it is just not about the object demonstrated—the photograph—but about the object related to the photograph by the relation of `being depicted in the photograph’ (for simplicity I assume that only one object is being depicted), while in descriptive uses a general proposition is expressed. For details about the difference between deferred and descriptive uses of indexicals see Kijania-Placek (2012a) and (under review).

Levinson’s argument originally concerned just bound, anaphoric and deictic uses of indexicals.

I use SmallCaps font style for formal counterparts of natural language quantifiers and predicates.

In what follows M is a model, g is an assignment of objects from the domain of the model to individual variables, i is a context, ⊨ is a satisfaction relation obtaining between a sentence (or an open formula) and a model and context, under an assignment; φ and ψ are open formulas, such as predicates, |A| signifies the cardinality of the set A, φMgi is the interpretation of formula φ in model M and context i under assignment g, “∩” and “\” are the standard set-theoretical operations of intersection and complement (compare Barwise and Cooper 1981; Peters and Westerståhl 2006; Kijania-Placek 2000).

An anonymous referee suggested that in this and similar examples the pronoun might possibly be analyzed as indexical over kinds, i.e. as functioning similarly to ‘the’ in “The tiger is an endangered species.” I agree that we could analyze the use of “he” in “He [pointing at a white tiger] is on the verge of extinction” as a case of (deferred) reference to the kind of white tiger (see footnote 8 for the difference between deferred and descriptive use of an indexical). But in this case we would treat the kind as a single abstract object (collective class or whatever kinds are in the ontological sense) and predicate a property that is applicable to such an objects, in contrast to attributing the property to individual tigers. In example (1), on the other hand, the property in question (being Italian) is applicable to individual popes and not to the property of being a pope or the kind of pope. For a more detailed argument against treating descriptive uses of indexicals as cases of reference to kinds see Kijania-Placek (2012a) and (under review).

I distinguish three types of descriptive uses of indexicals. They differ only with what triggers the mechanism of descriptive interpretation but the mechanism is the same in all cases. Only in the first type, exemplified by (1), the mechanism is triggered by an inconsistency between an indexical and a quantifier. In the second type, descriptive interpretation is triggered by the unavailability of basic interpretations, i.e. mainly the unavailability of a suitable referent in the context of utterance or the context of a reported belief (see Kijania-Placek 2012a and 2015). The third type of descriptive uses of indexicals is the case of irrelevance of the referential interpretation and it is exemplified by (2) and (9) below. See also Kijania-Placek (2012a), pp. 183–185, 205–223, 225–238.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for this example and for pointing out the need to clarify my presentation of this issue.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for insisting that I clarify this point.

The structure of the general proposition—here embedded in the modal operator—is provided by a binary quantifier and the quantifier is not always overt. If the sentence does not contain an overt quantifier, we reconstruct a covert binary quantifier, in analogy to the use of bare plurals for the expression of a quantified sentence. It will usually be the universal quantifier or the definite description, but which quantifier in particular is the relevant one is a contextual matter and depends mainly on what is predicated of the objects quantified over. Compare Carlson (1977) and Kratzer (1995). For the double—suppressive and constructive—role of context in descriptive interpretation of indexicals see Kijania-Placek (2015).

Thanks are due to an anonymous referee for suggesting that constructions such as "If I were you, φ” might provide further examples in favour of my thesis that some uses of indexicals require descriptive interpretations in the scope of modal operators. While I agree that such constructions indeed require descriptive interpretation of the indexical—since the point of such an utterance is to put yourself in somebody else’s shoes, it is both metaphysically impossible and inconceivable that the speaker is identical to the hearer—I do no think, contrary to the suggestion of the referee, that they are most naturally interpreted as indexicals embedded in the scope of epistemic modals. Rather, in interpreting such constructions I would suggest retaining a referential interpretation of “I” and relying on descriptive interpretation of “you”, an interpretation in which the semantic import of the indexical is a salient feature of the addressee. This interpretative move makes the metaphysical interpretation of the modal more salient: the speaker is considering φ from the point of view of a (metaphysically) possible word in which he, the speaker, is relevantly similar to the hearer, or finds himself in a relevantly similar situation. The details of such an analysis go, however, beyond the scope of this paper.

See Jaszczolt (1999) for a similar view.

References

Aristotle (2003) Topics. Books I and VIII with excerpts from related texts. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Barwise J, Cooper R (1981) Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguist Philos 4(1):159–219

Bezuidenhout A (1997) Pragmatics, semantic underdetermination and the referential/attributive distinction. Mind 106:375–409

Borg E (2002) Pointing at Jack, talking about Jill: understanding deferred uses of demonstratives and pronouns. Mind Lang 17:489–512

Braun D (2015) Indexicals. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition). Zalta EN (ed), URL: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/indexicals/. Cited 22 June 2015

Carlson GN (1977) A unified analysis of the English bare plural. Linguist Philos 1:413–456

Carston R (2002) Thoughts and utterances. The pragmatics of explicit communication. Blackwell, Oxford

Condoravdi C (2002) Temporal interpretation of modals: modals for the present and for the past. In: Beaver D, Kaufmann S, Clark B et al (eds) The construction of meaning. CSLI, Stanford, pp 59–88

DeRose K (1991) Epistemic possibilities. Philos Rev 107(2):581–605

Elbourne P (2005) Situations and individuals. MIT Press, Cambridge

Elbourne P (2008) Demonstratives as individual concepts. Linguist Philos 31:409–466

Fernando T (2005) Schedules in a temporal interpretation of modals. J Semant 22:211–229

Frege G (1892) Über Sinn und Bedeutung. Philosophie und Philosophische Kritik 100:25–50; transl. in Philos Rev 57:207–230

Frege G (1897) Logik. Unpublished (transl. in Hermes H, Kambartel F, Kaulbach F (eds) Posthumous writings. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1979, pp 126–151)

Frege G (1918) Der Gedanke. Eine Logische Untersuchung. Beiträge zur Philosophie des Deutschen Idealismus I:58–77 (transl. in Geach P (ed) Logical investigations. Blackwell, Oxford, 1977, pp 1–30)

Galery T (2008) Singular content and deferred uses of indexicals. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 20:157–194

Grice P (1989) Studies in the way of words. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hacking I (1967) Possibility. Philos Rev 76:143–168

Heim I (1988) The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. Garland Publishing Company, New York

Hunter J (2010) Presuppositional indexicals. Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin

Jaszczolt K (1999) Discourse, beliefs and intentions. Elsevier, Oxford

Kamp H (1981) A theory of truth and semantic representation. In: Groenendijk JA, Janssen T, Stokhof M (eds) Formal methods in the study of language. Foris, Dordrecht, pp 277–322

Kaplan D (1989) Demonstratives. In: Almog J, Perry J, Wettstein H (eds) Themes from Kaplan. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 481–563

Kijania-Placek, K (2000) Prawda i konsensus. Logiczne podstawy konsensualnego kryterium prawdy [Truth and consensus. A logical analysis of the consensus criterion of truth, in Polish]. Jagiellonian University Press, Kraków

Kijania-Placek K (2012a) Pochwała okazjonalności. Analiza deskryptywnych użyć wyrażeń okazjonalnych [In praise of indexicality. An analysis of descriptive uses of indexicals; in Polish]. Semper, Warsaw

Kijania-Placek K (2012b) Deferred reference and descriptive indexicals. Mixed cases. In: Stalmaszczyk P (ed) Philosophical and formal approaches to linguistic analysis. Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt, pp 241–261

Kijania-Placek K (2014) Situation semantics, time and descriptive indexicals. In: Stalmaszczyk P (ed) Semantics and beyond. Philosophical and linguistic inquiries, Walter De Gruyter, pp 127–148

Kijania-Placek, K (2015) Descriptive indexicals, propositional attitudes and the double role of context. In: Christiansen H, Stojanovic I, Papadopoulos G (eds) Modeling and Using Context. LNAI 9405, Springer, Dordrecht

Kijania-Placek, K (in preparation) Indexicals and names in proverbs

Kijania-Placek, K (under review) Descriptive indexicals, deferred reference, and anaphora

Kment B (2012) Varieties of modality. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2012 Edn). Zalta EN (ed). URL: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/modality-varieties/. Cited 22 June 2015

Kratzer A (1995) Stage-level and individual-level predicates. In: Carlson G, Pelletier FJ (eds) The generic book. Chicago University Press, Chicago, pp 125–175

Kripke S (2008) Frege’s theory of sense and reference: some exegetical notes. Theoria 74:181–218

Künne W (1992) Hybrid proper names. Mind 101(404):721–731

Levinson S (2000) Presumptive meanings: the theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT Press, Cambridge

Lewis D (1975) Adverbs of quantification. In: Keenan E (ed) Formal semantics of natural language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–15

Lewis D (1986) On the plurality of worlds. Blackwell, Oxford

Macagno F, Capone A (2015) Interpretative disputes, explicatures, and argumentative reasoning. Argumentation. doi:10.1007/s10503-015-9347-5

MacFarlane J (2011) Epistemic modals are assessment-sensitive. In: Weatherson B, Egan A (eds) Epistemic modality. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 144–178

Nunberg G (1978) The pragmatics of reference. Indiana Linguistics Club, Bloomington

Nunberg G (1991) Indexicals and descriptions in interpretation, Ts

Nunberg G (1992) Two kinds of indexicality. In: Barker C, Dowty D (eds) Proceedings from the second conference on semantics and linguistic theory. The Ohio State University, Columbus, pp 283–301

Nunberg G (1993) Indexicality and deixis. Linguist Philos 16:1–43

Nunberg G (2004) Descriptive indexicals and indexical descriptions. In: Reimer M, Bezuidenhout A (eds) Descriptions and beyond. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 261–279

Peters S, Westerståhl D (2006) Quantifiers in language and logic. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Poller, O (2008) Wyrażenia okazjonalne jako wyrażenia funkcyjne w semantyce Gottloba Fregego [Indexicals as functional expressions in the semantics of Gottlob Frege; in Polish]. Diametros, 17:1-29; published under the name Volha Kukushkina

Portner P (2009) Modality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Recanati F (1993) Direct reference: from language to thought. Blackwell, Oxford

Recanati F (2004) Literal meaning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Recanati F (2005) Deixis and anaphora. In: Szabo ZG (ed) Semantics vs. pragmatics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 286–316

Recanati F (2010) Truth-conditional pragmatics. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Sperber D, Wilson D (1986) Relevance: communication and cognition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sperber D, Wilson D (2004) Relevance theory. In: Horn LR, Ward G (eds) Handbook of pragmatics. Blackwell, Oxford

Stokke A (2010) Indexicality and presupposition. Explorations beyond truth–conditional information. Dissertation, University of St Andrews

von Fintel K, Gillies AS (2008) An opinionated guide to epistemic modality. In: Gendler TS, Hawthorne J (eds) Oxford studies in epistemology, vol 2. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 32–52

von Fintel K, Gillies AS (2011) ‘Might’ made right. In: Weatherson B, Egan A (eds) Epistemic modality. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 108–130

Acknowledgments

This work has been partly supported by the (Polish) National Science Centre 2013/09/B/HS1/02013 grant. I would also like to thank my two anonymous referees for their insightful comments which have helped me to improve this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kijania-Placek, K. Descriptive Indexicals and Epistemic Modality. Topoi 36, 161–170 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-015-9340-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-015-9340-5