Abstract

Purpose

Oral anticoagulants effectively prevent stroke/systemic embolism among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation but remain under-prescribed. This study evaluated temporal trends in oral anticoagulant use, the incidence of stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding, and economic outcomes among elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2–VASc scores ≥ 2.

Methods

Retrospective analyses were conducted on Medicare claims data from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2017. Non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients aged ≥ 65 years with CHA2DS2–VASc scores ≥ 2 were stratified by calendar year (2013–2016) of care to create calendar-year cohorts. Patient characteristics were evaluated across all cohorts during the baseline period (12 months before diagnosis). Treatment patterns and clinical and economic outcomes were evaluated during the follow-up period (from diagnosis through 12 months).

Results

Baseline patient characteristics remained generally similar between 2013 and 2016. Although lack of oral anticoagulant prescriptions among eligible patients remained relatively high, utilization did increase progressively (53–58%). Among treated patients, there was a progressive decrease in warfarin use (79–52%) and a progressive increase in overall direct oral anticoagulant use (21–48%). There were progressive decreases in the incidence of stroke/systemic embolism 1.9–1.4 events per 100 person years) and major bleeding (4.6–3.3 events per 100 person years) as well as all-cause costs between 2013 and 2016.

Conclusions

The proportions of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation who were not prescribed an oral anticoagulant decreased but remained high. We observed an increase in direct oral anticoagulant use that coincided with decreased incidence of clinical outcomes as well as decreasing total healthcare costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Highlights

-

Between 2013 and 2016, there was rapid and progressive temporal trends toward DOAC uptake supplanting warfarin prescriptions

-

This trend coincided with progressive reductions in stroke/SE, MB, and healthcare costs.

-

However, the proportions of overall OAC use increased by less than 10%, possibly indicating persistent OAC underutilization.

-

Further study is needed to determine where gaps in treatment may remain.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the United States, and the risk of developing AF increases with age [1]. AF incidence, prevalence, and AF-attributable mortality have increased in the US as the population has aged [1,2,3]. AF is estimated to currently affect as many as 6 million Americans and is expected to affect 12 million by 2030 [4, 5]. People with AF are at a five-fold greater risk of stroke than the general population [6]. Stroke contributes to the excess morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs observed among the AF patient population—particularly those aged ≥ 65 years [7].

Historically, the oral anticoagulant (OAC) warfarin has been the standard of care for stroke prevention among patients with non-valvular AF (NVAF). But warfarin is associated with increased risk of bleeding and requires dietary restrictions and consistent laboratory monitoring, all of which have resulted in the underutilization of warfarin and contributed to excess stroke among patients with NVAF [8, 9]. Since 2010, the United States Food & Drug Administration has approved four direct OACs (DOACs) developed to address this treatment gap: dabigatran (2010), rivaroxaban (2011), apixaban (2012), and edoxaban (2015) [10,11,12,13]. Based on clinical trial evidence of noninferior or superior stroke prevention with generally lower bleeding rates among DOACs vs warfarin, 2014 clinical guidelines recommended DOACs over warfarin for patients with NVAF and risk factors for stroke, with the recommendation reiterated in 2019 [14, 15]. Since their introduction into clinical practice, DOACs have been associated with overall similar or lower risk of stroke and generally lower risk of major bleeding (MB) as compared with warfarin [16, 17]. After the inclusion of DOACs in clinical guidelines, their utilization has increased, while warfarin use has decreased [18].

Nonetheless, underutilization of OAC treatment in clinical practice has been reported from the period before the introduction of DOACs through early post-market surveillance [18,19,20,21,22]. Moreover, this underutilization has been associated with adverse outcomes [23, 24]. The timing of these prior studies in relation to DOAC rollouts underscores the importance of understanding the evolving impact of DOACs on real-world NVAF treatment patterns and associated outcomes. Several real-world studies have observed shifts toward guideline-recommended DOAC treatment for NVAF in Europe, Australia, and East Asia.[25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Some included observations of associated reductions in stroke and MB incidence [27, 30, 33]. Some US studies have observed temporal trends in OAC use around the time of new guidelines and DOAC rollouts. However, they lacked stratification for stroke risk as well as data on clinical and economic outcomes, and they had relatively small sample sizes [34,35,36,37,38]. Moreover, they differed in patient populations and results. For example, a national registry study and a Medicare dataset study (2013–2016 and 2010–2017, respectively) reported increasing trends in OAC use during data years after guideline implementation [36, 37]. In contrast, a VA dataset study found no appreciable change in OAC use (2007–2016) [38]. Thus, more comprehensive, chronological evidence is needed to characterize associations between guideline introduction, DOAC uptake, and patient outcomes among US patients with NVAF and high stroke risk.

Therefore, the authors undertook this retrospective analysis of temporal trends in OAC use, stroke/SE and MB incidence, and healthcare costs among Medicare patients with NVAF and high stroke risk scores from 2013–2016.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective cohort study utilized the 100% US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) fee-for-service Medicare dataset from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2017. Data included medical and pharmacy claims from Medicare Parts A [hospitalization, skilled nursing facility (SNF), and hospice care], B [outpatient care, durable medical equipment (DME), home health agency (HHA)], and D (prescription drug coverage). Medical claims were evaluated using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM/ICD-10-PCS) diagnosis and procedure codes as well as Health Care Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) and Current Procedural Terminology codes; pharmacy claims were identified using NDC codes.

Patient selection

For each year of the identification period (2013–2016), patients aged ≥ 65 years with ≥ 1 inpatient or ≥ 2 outpatient claims (≥ 7 days apart and within 365 days) for AF (ICD-9 427.3; ICD-10 I48 any diagnosis position) were selected within calendar year cohorts. The first observed AF diagnosis of that year was designated as the index date. For each calendar year cohort, patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy coverage for 12 months prior to the index date through 12 months after the index date (patients who died during follow-up were included to avoid selection bias). Patients were required to have a CHA2DS2 -VASc score ≥ 2 and were excluded if they had rheumatic mitral valvular heart disease or valve replacement procedure at any time before or on the day of AF diagnosis (Supplemental Table 1).

Baseline characteristics

Age, sex, and race were ascertained on the index date (AF diagnosis), and baseline clinical characteristics were examined during the 12-month pre-index period within each calendar year cohort. Mean CHA2DS2-VASc and modified HAS-BLED scores were calculated to evaluate risk of stroke and major bleeding, respectively [39]. The CHA2DS2-VASc score evaluates stroke risk on a 0–9 scale calculated based on 8 weighted factors: congestive heart failure; hypertension; age ≥ 75 years; diabetes mellitus; history of stroke, thromboembolism, or transient ischemic attack; vascular disease; age 65–74 years; and sex category [39]. The modified HAS-BLED score estimates the 1-year risk of MB on a 0–8 scale calculated based on 6 weighted factors: hypertension, abnormal kidney and/or liver function, stroke, bleeding, age > 65 years, and prior use of alcohol/drugs or medications associated with bleeding risk (the labile international normalized ratio, lab values, and self-reported alcohol consumption levels included in the standard HAS-BLED score were not available) [40].

Outcomes

Outcomes were examined during the follow-up period, which was defined as the index date through 12 subsequent months for each calendar-year cohort, with all observed outcomes recorded for that cohort. Reported treatment outcomes included the overall proportions of patients prescribed OACs on or after the index date, stratified by OAC type (warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban) and the proportion of patients not prescribed OACs during the follow-up period.

Clinical and economic outcomes were examined during the 12-month follow-up period from NVAF diagnosis (index date) until death or end of follow-up. The clinical outcomes were incidence rates of stroke/SE and MB. These outcomes were defined by hospitalizations with a principal diagnosis for stroke/SE or MB, respectively. Stroke/SE included ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and systemic embolism. MB included gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and bleeding at other key sites [41, 42]. Economic outcomes included all-cause total healthcare costs, which were comprised of inpatient, outpatient / emergency room (ER), pharmacy, and other costs (DME, HHA, hospice, SNF) from medical/pharmacy claims.

Statistical analysis

All study variables were described with standard summary statistics among calendar year cohorts: numbers and percentages were reported for categorical variables; means and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for continuous variables. Clinical outcome incidence rates were presented per 100 person-years, calculated as the number of patients with events of interest divided by time at risk for developing the event (divided by 100) within the year of interest.

The mean healthcare costs were reported per person per month (PPPM) and calculated by adding the costs from inpatient, outpatient/ER, pharmacy, and other (DME, SNF, hospice, and HHA) settings. The costs were adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index from the US Department of Labor. Data analysis was performed using statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Institutional review board approval

As this study did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board review. Both the datasets and the security of the offices where analysis was completed (and where the datasets are kept) meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Results

Study population

After selection criteria application, there was a progressive increase in the number of patients with NVAF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥ 2 each calendar year from approximately 1.6 million in 2013 to approximately 1.9 million in 2016 (Supplemental Table 2). Patient demographics were generally consistent across the four calendar year cohorts; mean ages were ~ 80 years, and most patients were white (~ 90%). The proportion of female patients decreased slightly over the study period (57–54%). Across the calendar years, the mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was approximately 4.6 and the mean modified HAS-BLED score was 3.2 (Table 1).

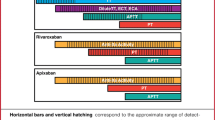

Proportions of oral anticoagulant treatment

Over the 4 years from 2013 to 2016, the proportion of eligible patients not treated with OACs slightly but progressively decreased from 47 to 42% but till remained high (the proportion of overall OAC-treated patients increased from 53 to 58%; Fig. 1). Among the OAC-treated from 2013–2016 (Fig. 2), DOAC prescriptions also became progressively more common, with proportions of patients prescribed warfarin progressively decreasing from 79 to 52%; DOACs progressively increasing from 21 to 48%. Among DOACs, proportions for apixaban and rivaroxaban progressively increased (from 2 to 23% and 10% to 18%, respectively) while dabigatran progressively decreased from 9 to 7%. Edoxaban prescriptions began in 2015 and remained below 1% through 2016 (data not shown).

Total OAC treatment proportions among Medicare patients with NVAF at increased stroke risk from 2013–2016. For each calendar year, OAC prescriptions were captured on the NVAF diagnosis date or during the 12 months after the NVAF diagnosis. OAC oral anticoagulant, NVAF non-valvular atrial fibrillation

Type of OAC treatment among OAC prescribed medicare patients with NVAF at increased stroke risk from 2013–2016. For each calendar year, OAC prescriptions were captured on the NVAF diagnosis date or during the 12 months after the NVAF diagnosis. OAC oral anticoagulant, NVAF non-valvular atrial fibrillation

Incidence of stroke/SE and MB

The observed temporal trends in treatment patterns coincided with a generally progressive decrease in the yearly incidence rates of stroke/SE and MB from 2013–2016. Incidence rates of stroke/SE decreased from 1.9 to 1.4 per 100 person years (Fig. 3). All types of stroke/SE decreased, including hemorrhagic stroke (0.3–0.1 per 100 person years), ischemic stroke (1.5–1.2 per 100 person years), and SE (0.13–0.08 per 100 person years). A similar trend was observed for MB, which decreased from 4.6 to 3.3 per 100 person years. A reduction was observed for all types of MB, including ICH, which decreased from 0.6 to 0.5 per 100 person years (Fig. 3).

Incidence rates of stroke/SE and MB per 100 person years among Medicare patients with NVAF at increased stroke risk from 2013–2016. Incidence rates of stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding were calculated per 100 person-years. For each calendar year, stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding were measured on the non-valvular atrial fibrillation diagnosis date or during the 12 months after the non-valvular atrial fibrillation diagnosis, regardless of oral anticoagulant treatment

Healthcare costs

Although there was some directional variation, overall follow-up total all-cause healthcare costs (outpatient/ER, inpatient, other, pharmacy) also progressively decreased from $2563 PPPM in 2013 to $2372 PPPM in 2016. Inpatient costs progressively decreased from $933 to $752 PPPM, while outpatient/ER costs remained relatively consistent across the 4 years ($664–$693); pharmacy costs increased from $329 to $405 PPPM (Fig. 4).

Follow-up total healthcare costs (PPPM) among Medicare patients with NVAF at increased stroke risk from 2013–2016. Total costs were calculated per patient per month during the 12 months on or after NVAF diagnosis, regardless of OAC treatment. Total costs (adjusted to 2017 dollars) included medical and pharmacy costs, of which medical costs include inpatient, outpatient/ER, and other costs (durable medical equipment, home health agency, hospice, and skilled nursing facility). NVAF non-valvular atrial fibrillation, PPPM per patient per month, USD United States Dollars

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive, temporal evaluation of OAC treatment and outcome trends in the US after the 2014 introduction of clinical guideline recommendations for the use of the CHA2DS2-VASc risk assessment tool and preference of DOACs over warfarin for patients with NVAF at increased stroke risk. The findings describe a marked uptake of DOACs (from roughly one-fifth to half of OAC-treated patients) in place of warfarin. This shift coincided with generally progressive reductions in stroke/SE and MB incidence (including a steep reduction when guidelines first were implemented) as well as healthcare costs during the 4-year study period. However, we observed a smaller increase in overall OAC utilization (53–58%) within the context of persistently high proportions of eligible patients not prescribed OACs (47–42%).

Our findings add to the timeline of real-world observations of OAC treatment for NVAF after the introduction of DOACs and are generally consistent in directionality [19,20,21,22,23, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. In their cross-sectional registry study of > 400,000 patients with AF from 2008–2012, Hsu et al. found that ~ 45% were treated with an OAC over the entire study period—among whom 90% were prescribed warfarin, 8% dabigatran (2010 FDA approval), and 2% rivaroxaban (2011 FDA approval) [20]. Apixaban (2012 FDA approval) was not included. As compared with our results for 2013 (OAC: 53%; warfarin: 79%; dabigatran: 9%, rivaroxaban: 10%, apixaban: 2%), and given that the study population in Hsu et al. was not stratified by calendar year and was somewhat younger with lower stroke risk [mean age: 71 years (vs 80.5); CHA2DS2–VASc score: 3.7 (vs 4.7)], the two sets of results generally align to describe an overall progression of both increased DOAC use and increased overall OAC use. Similar overlapping temporal trends were also observed in the US by Ashburner et al. (2010–2015), Alcusky et al. (2011–2016), Steinberg et al. (2013–2016), and Zhu et al. (2010–2017) [34,35,36,37]. While Rose et al. (2007–2016) also observed a marked uptake of DOAC use during a similar period, they did not observe substantive changes in overall OAC use. However, this discrepancy may be attributable to differing patient characteristics of the VA database [38]. Upward trends have also been observed in Europe, Australia, and East Asia [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Thus, while continued research across varying patient populations is necessary, the preponderance of existing evidence is consistent.

Notably, the overall OAC use we observed is generally consistent with US real-world studies that suggest possible underutilization at earlier periods, during a generally similar period (2010–2015), and more recently (2018) [18,19,20,21,22] [43], More recent data in particular raise questions about why underuse persists despite guideline implementation. Ko et al. found that among Medicare beneficiaries, 67.1% of patients with incident AF in 2020 had not initiated an OAC within 12 months of diagnosis [44]. While legitimate considerations for contraindications due to comorbidity, polypharmacy, extremely high bleeding risk, or unobserved antiplatelet or aspirin prescription may play a role, there may also be some clinical inertia attributable to inappropriate concerns regarding older age, sex, frailty, or moderate bleeding risk, as well as suboptimal guideline awareness [23, 24, 45]. A study by Navar et al. suggests differences at the provider‐ and health-system‐level are more of a driving factor in the underutilization of DOAC treatment than patient level factors among patients with NVAF [45]. Regardless, more research is necessary to help guide clinical decision-making.

There are scarce data currently available that examine temporal trends in stroke/SE and MB among patients with NVAF during comparable periods in the US. Hohnloser et al. conducted a German retrospective claims study that found a progressive 24% reduction in adjusted stroke incidence from 2011–2016, in parallel with DOAC uptake following the implementation of similar clinical guidelines in 2013 [27]. Although populations and payer systems differed, Hohnloser et al. found a decrease in crude stroke/SE rates (1.9–1.6 per 100 person years) roughly comparable to our (unadjusted) results (1.9–1.4 per 100 person years). However, crude MB rates in Hohnloser et al. increased slightly over the period, from 1.9 to 2.1 per 100 person years, in contrast to 4.6–3.3 per 100 person years observed in our study. Moreover, while studies by Maggioni et al. and Narita et al. found reduced proportions of hospitalizations for stroke in parallel with DOAC uptake in Italy and Japan, respectively [30, 33], Maggioni et al. found a slight increase in hospitalizations for MB. Ding et al. observed the stroke trend in Sweden from 2001–2020 noting similar results in stroke reduction and increase in DOAC use, but highlighted that as of 2020 one in four strokes among elderly Swedish patients was preceded by or concurrent with an AF diagnosis [46]. While these discrepancies may be attributable to differing patient characteristics and specifics of national-level guidelines, they warrant more research to verify our findings in US datasets stratified by year.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous data on US costs for patients with NVAF at the national level stratified by year. As a general benchmark, an internal Medicare retrospective study of all Medicare patients with AF from 2004–2008 found approximate costs of $2,000 PPPM (based on yearly costs of $24,000 in 2009 US dollars) [47]. A recent study found that patients with AF incurred ~ $25,000 PPPY higher healthcare costs compared to patients without AF [48]. Another retrospective claims analysis of Medicare patients treated with OACs between 2013–2014 found a range of $3180 to $3878 PPPM (2014 US dollars) [49] as compared with $2563 PPPM among all patients with NVAF in our 2013 cohort (2017 US dollars), reflecting higher costs among the treated. Notably, this study was among several retrospective analyses of Medicare patients that showed lower overall healthcare costs among patients prescribed DOACs as compared with warfarin. Given the increase in proportions of those prescribed DOACs over our study period, this may have contributed to the observed reduction in costs. The observed reduction in cost is driven by the reduced inpatient cost over time, which is likely the result of reduced stroke and/or bleeding events due to patients switching to DOACs over our study period. Despite the coinciding trends of increased DOAC use, reduced events and reduced inpatient cost over time, further research is needed to determine a causal relationship between increased DOAC use and reduced events and reduced cost. Results warrant continued research that adjusts for patient characteristics between calendar year cohorts.

Taken together and in context with similar trends observed abroad, these results provide insight on the interplay between guideline introduction and uptake time for new agents that can help inform decision-making for clinicians, payers, and policy makers. Future research should investigate the reasons for clinical practices apparently contrary to the evidence and guidelines.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study of its kind stratified by year to analyze a large, highly representative dataset at the national level; the results provide a highly inclusive and comprehensive descriptive observation of the treatment landscape during a time of evolution of oral anticoagulation in the US. Nonetheless, results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. For instance, all claims data are collected for administrative purposes rather than research and therefore lack certain clinical information such as actual medication administration as well as observation of samples and over-the-counter medication. Moreover, claims are subject to coding discrepancies. As with all retrospective analyses, interpretation of these data is limited to observation of associations rather than inference of causality, and observed coinciding trends in this study should be interpreted accordingly. Other limitations specific to this study include the absence of information on treatment switching and discontinuation, as patients were assigned to OAC-treated cohorts based only on the first prescription received during the follow-up period. In addition, this study was performed in a Medicare population aged ≥ 65 years; results may not be generalizable to younger patients, those at lesser risk, and those with other forms of insurance. Also notable, the clinical guidelines for OAC treatment among patients with NVAF were not yet implemented during the first calendar year examined and have changed again since the end of the study period. We reported treatment among both male and female patients with NVAF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥ 2 in alignment with 2014 guidelines; however, the most recent guidelines recommend treatment for males with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥ 2 and females with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥ 3.15 Finally, the calendar year cohorts were not balanced for variation in patient characteristics, so results should be interpreted accordingly. Nonetheless, the consistency of observed progressive directional trends with similar findings in other countries warrant continued research.

Conclusion

This study evaluated temporal trends between 2013 and 2016 in OAC treatment and related clinical and economic outcomes among a large Medicare patient population with NVAF at increased risk of stroke. The results reveal rapid and progressive temporal trends toward DOAC uptake supplanting warfarin prescriptions, which chronologically follow clinical guidelines (2014) calling for the use of DOAC prescriptions instead of warfarin for patients with NVAF at high risk of stroke. This trend coincided with progressive reductions in stroke/SE, MB, and healthcare costs. However, the proportions of overall OAC use increased by less than 10%, possibly indicating persistent OAC underutilization. Further study is needed to determine where gaps in treatment may remain.

Data availability

The raw insurance claims data used for this study originate from Medicare data, which are available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid through ResDAC (https://www.resdac.org/). Other researchers could access the data through ResDAC, and the inclusion criteria specified in the Methods section would allow them to identify the same cohort of patients we used for these analyses.

References

Heart disease: Atrial fibrillation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/atrial_fibrillation.htm. Updated Sept 2020. Accessed Feb 2021

Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P et al (2015) 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet 386(9989):154–162

DeLago AJ, Essa M, Ghajar A et al (2021) Incidence and mortality trends of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter in the United States 1990 to 2017. Am J Cardiol 148:78–83

Kornej J, Börschel CS, Benjamin EJ, Schnabel RB (2020) Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the 21st century: novel methods and new insights. Circ Res 127(1):4–20

Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X (2013) Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol 112(8):1142–1147

Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB (1991) Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke 22(8):983–988

Yousufuddin M, Young N (2019) Aging and ischemic stroke. Aging (Albany NY) 11(9):2542–2544

Patel P, Pandya J, Goldberg M (2017) NOACs vs. warfarin for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Cureus 9(6):1395

Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A et al (2020) 2020 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on management of bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulants: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 76(5):594–622

United States Food & Drug Administration label (2010) Pradaxa. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022512s027lbl.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

United States Food & Drug Administration label: Xarelto. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/022406s028lbl.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

United States Food & Drug Administration label: Eliquis. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202155s000lbl.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

United States Food & Drug Administration label: Savaysa. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206316lbl.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, ACC/AHA Task Force Members et al (2014) AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 130(23):2071–2104

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H et al (2019) 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 140(2):e125–e151

Deitelzweig S, Farmer C, Luo X et al (2018) Comparison of major bleeding risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation receiving direct oral anticoagulants in the real-world setting: a network meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 34(3):487–498

Coleman CI, Briere JB, Fauchier L et al (2019) Meta-analysis of real-world evidence comparing non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants with vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Mark Access Health Policy 7(1):1574541

Generalova D, Cunningham S, Leslie SJ, Rushworth GF, McIver L, Stewart D (2018) A systematic review of clinicians’ views and experiences of direct-acting oral anticoagulants in the management of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84(12):2692–2703

Al-Khatib SM, Pokorney SD, Al-Khalidi HR et al (2020) Underuse of oral anticoagulants in privately insured patients with atrial fibrillation: a population being targeted by the IMplementation of a randomized controlled trial to imProve treatment with oral AntiCoagulanTs in patients with atrial fibrillation (IMPACT-AFib). Am Heart J 229:110–117

Hsu JC, Maddox TM, Kennedy KF et al (2016) Oral anticoagulant therapy prescription in patients with atrial fibrillation across the spectrum of stroke risk: insights from the NCDR PINNACLE registry. JAMA Cardiol 1(1):55–62

Suarez J, Piccini JP, Liang L et al (2012) International variation in use of oral anticoagulation among heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 163(5):804–811

Lubitz SA, Khurshid S, Weng LC et al (2018) Predictors of oral anticoagulant non-prescription in patients with atrial fibrillation and elevated stroke risk. Am Heart J 200:24–31

Di Fusco M, Sussman M, Barnes G et al (2020) The burden of nontreatment or undertreatment among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with elevated stroke risk: a systematic literature review of real-world evidence. Circulation 142:A1565

Hsu JC, Freeman JV (2018) Underuse of vitamin K antagonist and direct oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: a contemporary review. Clin Pharmacol Ther 104(2):301–310

Zimny M, Blum S, Ammann P et al (2017) Uptake of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anti coagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation—a prospective cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly 147:w14410

Gadsbøll K, Staerk L, Fosbøl EL et al (2017) Increased use of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: temporal trends from 2005 to 2015 in Denmark. Eur Heart J 38(12):899–906

Hohnloser SH, Basic E, Nabauer M (2019) Uptake in antithrombotic treatment and its association with stroke incidence in atrial fibrillation: Insights from a large German claims database. Clin Res Cardiol 108(9):1042–1052

Maura G, Billionnet C, Drouin J, Weill A, Neumann A, Pariente A (2019) Oral anticoagulation therapy use in patients with atrial fibrillation after the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: findings from the French healthcare databases, 2011–2016. BMJ Open 9(4):e026645

Esposti LD, Briere JB, Bowrin K et al (2019) Antithrombotic treatment patterns in patients with atrial fibrillation in Italy pre- and post-DOACs: The REPAIR study. Future Cardiol 15(2):109–118

Maggioni AP, Dondi L, Andreotti F et al (2020) Four-year trends in oral anticoagulant use and declining rates of ischemic stroke among 194,030 atrial fibrillation patients drawn from a sample of 12 million people. Am Heart J 220:12–19

Admassie E, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR (2017) Changes in oral anticoagulant prescribing for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 120(7):1133–1138

Lee SR, Choi EK, Han KD, Cha MJ, Oh S, Lip GYH (2017) Temporal trends of antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in Korean patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the era of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE 12(12):e0189495

Narita N, Okumura K, Kinjo T et al (2020) Trends in prevalence of non-valvular atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation therapy in a Japanese region—analysis using the National Health Insurance Database. Circ J 84(5):706–713

Ashburner JM, Singer DE, Lubitz SA, Borowsky LH, Atlas SJ (2017) Changes in use of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation within a primary care network associated with the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants. Am J Cardiol 120(5):786–791

Alcusky M, McManus DD, Hume AL, Fisher M, Tjia J, Lapane KL (2019) Changes in anticoagulant utilization among United states nursing home residents with atrial fibrillation from 2011 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc 8(9):e012023

Steinberg BA, Shrader P, Thomas L et al (2017) Factors associated with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation: results from the outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation II (ORBIT-AF II). Am Heart J 189:40–47

Zhu J, Alexander GC, Nazarian S, Segal JB, Wu AW (2018) Trends and variation in oral anticoagulant choice in patients with atrial fibrillation, 2010–2017. Pharmacotherapy 38(9):907–920

Rose AJ, Goldberg R, McManus DD et al (2019) Anticoagulant prescribing for non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the veterans health administration. J Am Heart Assoc 8(17):e012646

Shariff N, Aleem A, Singh M, Li YZ, Smith SJ (2012) AF and venous thromboembolism—pathophysiology, risk assessment and CHADS-VASc score. J Atr Fibrillation 5(3):649

Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH (2010) A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess one year risk of major bleeding in atrial fibrillation patients: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 138(5):1093–1100

Thigpen JL, Dillon C, Forster KB et al (2015) Validity of international classification of disease codes to identify ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage among individuals with associated diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 8(1):8–14

Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA (2011) An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20(6):560–566

Gluckman TJ, Ali A, Wang M, Mun H, Alfred S, Petersen JL (2019) Underutilization of oral anticoagulant therapy in at-risk patients with atrial fibrillation—insights from a multistate healthcare system. Circulation 140:A13987

Ko D, Lin KJ, Bessette LG et al (2022) Trends in use of oral anticoagulants in older adults with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation, 2010–2020. JAMA Netw Open 5(11):e2242964. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.42964

Navar AM, Kolkailah AA, Overton R et al (2022) Trends in oral anticoagulant use among 436 864 patients with atrial fibrillation in community practice, 2011 to 2020. J Am Heart Assoc 11(22):e026723. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.026723

Ding M, Ebeling M, Ziegler L, Wennberg A, Modig K (2023) Time trends in atrial fibrillation-related stroke during 2001–2020 in Sweden: a nationwide, observational study. Lancet Reg Health Europe. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100596

(2010) Health services utilization and medical costs among medicare atrial fibrillation patients, data brief. Avalere website. https://avalere.com/research/docs/Avalere-AFIB_Report-09212010.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

Deshmukh A, Iglesias M, Khanna R, Beaulieu T (2022) Healthcare utilization and costs associated with a diagnosis of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm O2 3(5):577–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hroo.2022.07.010

Amin A, Keshishian A, Trocio J et al (2020) A real-world observational study of hospitalization and health care costs among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients prescribed oral anticoagulants in the US Medicare population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 26(5):639–651

Acknowledgements

Editorial Assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Christopher Moriarty of STATinMED, LLC which is a paid consultant to Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb; while the authors have financial relationships with at least 1 of these companies, neither business entity influenced the design, conduct, or reporting of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally in the development of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Brett D. Atwater has received research grants from Abbott and Boston Scientific and acts as adviser to, Biotronik, Biosense Webster, Pfizer and Medtronic. Lisa Rosenblatt, Jenny Jiang, and Mauricio Ferri are paid employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Jennifer D. Guo was a paid employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb at the time of this study. Cristina Russ is a paid employee of Pfizer. Allison Keshishian and Rachel Delinger were a paid employees of STATinMED at the time of this study; STATinMED is a paid consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript. Huseyin Yuce has no potential conflicts to report.

Ethics approval

This is an observational study. Since this study did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review by Solutions IRB. Both the datasets and the security of the offices where analysis was completed (and where the datasets are kept) meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Solutions IRB determined this study to be EXEMPT from the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)’s Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR 46) under Exemption 4: Research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. The HIPAA Authorization Waiver was granted in accordance with the specifications of 45 CFR 164.512(i). This project was conducted in full accordance with all applicable laws and regulations, and adhered to the project plan that was reviewed by Solutions Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

As this retrospective study utilized deidentified claims data, individual patient consent was not required.

Consent to publish

As this retrospective study utilized deidentified claims data, individual patient consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Atwater, B.D., Guo, J.D., Keshishian, A. et al. Temporal trends in anticoagulation use and clinical outcomes among medicare beneficiaries with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Thromb Thrombolysis 57, 1–10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-023-02838-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-023-02838-2