Abstract

Expressives are words that convey speakers’ attitudes towards a particular object or situation. Consider two examples:

-

Attributive: That f**khead Jeremy forgot the turkey.

-

Predicative: Jeremy is a f**khead.

In both examples the word f**khead communicates some expressive content - the negative attitude of the speaker. However, only in Predicative does it appear to contribute to the truth-conditional content. The task is to explain the semantics of the word f**khead when it seemingly behaves wildly differently in different syntactic positions. In this paper I consider several good candidates for dealing with f**khead occurring in Predicative position: Expressivist and Descriptive approaches that treat f**khead in Predicative as purely descriptive; and Expressive-Contextualism that treats Predicative as communicating to both expressive and descriptive dimensions. I show that none of the options fully capture the meaning of f**khead. Treating Predicative as purely descriptive leaves out the highly important expressive element, whilst Contextualist semantics does not seem as a suitable descriptive theory for expressives. I finally present a novel hybrid account that combines Expressivist semantics with Relativism. I call this view Expressive-Relativism. I show that by adopting Expressive-Relativism we can not only explain the relationship of f**khead in Attributive and Predicative, but also give a suitable descriptive theory that captures the truth-conditions of Predicative.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Mark and Jeremy are preparing Christmas dinnerFootnote 1. To Mark’s horror, it becomes clear that Jeremy has forgotten to provide the turkey that they had agreed he would acquire. Mark’s report of the situation makes his attitude towards Jeremy very clear:

-

Attributive: That f**khead Jeremy forgot the turkey.Footnote 2

A while after, still angry, Mark utters the following to express his attitude towards Jeremy:

-

Predicative: Jeremy is a f**khead!

Both utterances label Jeremy as a f**khead, and this label clearly is a subjective one: being a f**khead does not seem to be the same kind of objective property as being a turkey. Mark’s labelling of Jeremy serves to capture the attitude that Mark has towards Jeremy. But there is a puzzling disparity in how this happens. In Attributive, the attitude expressed appears independent of the truth-conditional content: Attributive is true just in case Jeremy forgot the turkey. But transposing the syntactic position of f**khead to the predicative position in Predicative makes an attempt to treat the term as truth-conditionally inert more problematic as there is simply no truth-conditional content left if we deny that the word makes a contribution to those truth-conditions. And yet, we have exactly the same word in each case. There does not seem to be an obvious semantic difference between the two episodes of labelling Jeremy as a f**khead: whatever f**khead means seems to be what Jeremy is labelled as in both cases. How should the puzzle be solved? Several options are up for grabs:

-

(i)

Pure Expressivist Semantics (Potts 2005, 2007a, b)—the word f**khead is highly sensitive to its syntactic position. Whilst Attributive expresses content that is completely independent from truth values, Predicative contributes distinct descriptive content, lacking the expressive element possessed by Attributive.

-

(ii)

Early Expressivism/Emotivism (Stevenson 1937)—borrowing ideas of how one might deal with ethical language (e.g. good, bad), this option would deny that Predicative has any truth-conditional content and rather means something like “Boo to Jeremy!". Note that such account would also deny that there’s any descriptive content in the case of Attributive as well.

-

(iii)

Descriptive Approaches (Lasersohn 2007, 2017)—argue that f**khead can be given a purely descriptive account using similar semantics to those that account for predicates of personal taste (words like fun, tasty, etc.). Whilst descriptive approaches disagree with Expressivist approaches [such as (i)] in regards to Attributive, they agree that f**khead in Predicative should be treated in a descriptive manner.

-

(iv)

Hybrid accounts (Gutzmann 2015, 2016), and the one presented in this paper—reject the idea that expressive and descriptive contents are independent. Such accounts give a treatment of Predicative that accounts for both descriptive and expressive elements, normally, through a combination of Expressivist semantics with some descriptive theory. The link between Attributive and Predicative is explained by both occurrences carrying expressive content.

In what follows I will show why options (i) and (iii) are not satisfactory to explain the relationship between Attributive and PredicativeFootnote 3. I’ll argue, pace options (i) and (iii), that denying f**khead expressive content is a mistake. We will see in Sect. 3.1 that there’s linguistic data supporting the claim that expressives carry both expressive and descriptive contents. I will show that to accommodate this we need a theory which can account for both expressive and descriptive dimensions. In Sect. 4, I will consider a theory which corresponds to option (iv) put forth by Gutzmann (2015, 2016). After showing its downfalls I will present my own suggestion for a hybrid account, this will be the focus of Sect. 5. The hybrid theory presented in this paper combines Expressivist semantics with Relativism, I call it Expressive-Relativism. Expressive-Relativism allows for the expressive content to be captured via the Expressivist semantics, whilst the descriptive content is captured via Relativism.

2 Expressivist semantics

Before we can explore option (i) and its solution to the puzzle outlined in the introduction, I will discuss some properties of expressives that will be relevant for this paper, these properties have been noted byPotts (2005, 2007a, 2007b)Footnote 4.

2.1 Independence

Expressive content resides in a different dimension to the descriptive content. Whereas descriptive terms contribute to the proposition and thus are truth-conditional, expressives only occupy the expressive dimension and bear no influence on the truth-conditionsFootnote 5. We can test whether the expressive contributes to the truth-conditional content with a couple of tests. Firstly, we can see whether the truth-conditions of a proposition change when we remove the expressive:

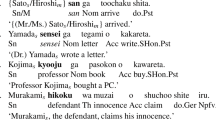

When the expressive is removed in (1b), the truth-conditions stay the same, which gives us a good reason to think that the expressive contributes to the expressive dimension only. Secondly, we can see if denying an utterance will have an effect on the expressive:

Dobby’s denial in (2a), only targets the descriptive content, i.e. she does not deny that Jeremy is a f**khead. We can see that direct denial of the expressive content is not possible as shown by the infelicity of her attempt in (2b). Both of these tests suggest that the expressive content does not contribute to the descriptive dimension and thus is independent from it.

2.2 Perspective dependence

Expressives are always evaluated from a certain perspective. This perspective is most often the speaker’s, for example:

Here we see that it is the speaker’s negative attitude being portrayed towards Webster. Now consider:

In (4), the speaker is no longer conveying a negative attitude towards Webster, but rather she’s communicating her father’s attitude. As such we need to allow for the expressive to be evaluated from a perspective that is someone other than the speaker, in the example above the speaker’s father. To handle cases like these, we will need to include a judge parameter in the context of utterance that the expressive is sensitive to. The judge parameter will pick out the relevant agent (or judge) from the context and the expressive will be evaluated from that perspective (I will elaborate on this below). Regardless of whether the perspective is of the speaker or some other judge, the important point is that expressives are always evaluated from some perspective.

2.3 Descriptive ineffability

Expressive content cannot be given a full descriptive paraphrase. By a full descriptive paraphrase I simply mean, as does Potts, that “[s]peakers are never fully satisfied when they paraphrase expressive content using descriptive, i.e., nonexpressive, terms" (Potts 2007b, p. 166).

Potts notes that the word bastard can be “claimed to mean ‘vile contemptible person’. But this paraphrase misses its wide range of affectionate uses", as well as, uses that apply to objects rather than people (Potts 2007b, pp. 177–178). For example:

Furthermore, even if we tried to paraphrase bastard in (6) it’s clear that the paraphrase would be missing something. If we paraphrase bastard laptop as bad/useless laptop then we would be missing the potency of the agent’s attitude in (6).

To account for the expressive properties outlined above and the expressive content, I will present an informal discussion of expressive semantics. To begin, take a set of non-empty contexts, each context containing a world parameter (picks out the relevant world of the context), time parameter (picks out the relevant time of the context), and agent parameter (picks out the relevant agent of context). To capture the expressive content Potts introduces two additional parameters - the judge parameter (picks out the relevant judge of the context) and the expressive setting (captures the attitude of the judge of the context). The contexts will play two different kinds of roles. On the one hand we have a context which plays a content determining role (the context of utterance or CU), on the other hand we have a context which plays an evaluation determining role (context of assessment or CA). For example, if we take an utterance containing the indexical ‘I’, e.g. ‘I am hungry’, we will need to pick out an agent from the context in which the utterance is made in order to determine the referent, and thus the content, of the sentence. To know the truth-value of the utterance ‘I am hungry’, we need to assess whether the agent of that world is in fact hungry, thus we look to the context of assessmentFootnote 6.

As noted rather than having a single parameter for individuals the agent parameter is distinguished from the judge parameter. To determine the content of an utterance containing an expressive, we look to the judge parameter in the CU. This will help to account for the perspective dependence feature of expressives (expressive content is always evaluated from some perspective). This is an extremely important feature in accounting for expressive content for it highlights the subjective nature of expressives. The content of an expressive utterance will always depend on who the judge of the utterance is and not some objective feature in the world. The perspective is typically the speaker’s, but need not be, as shown with the Kratzer example. Although the agent and the judge often coincide this is not always the case as such two different parameters are needed.

The second relevant element for capturing expressive content is the expressive settingFootnote 7. When an expressive is uttered it affects the expressive setting by introducing the judge’s attitude towards some entity or situation into the context of utterance. The expressive content just is the negative/neutral/positive attitude of the judge captured within the expressive setting. Recall Attributive:

-

Attributive: That f**khead Jeremy forgot the turkey!

Take \(cu_{1}\) to be a context where Mark feels indifferently towards Jeremy and then after learning of the turkey fiasco, he utters Attributive. The expressive f**kchead introduces Mark’s negative attitude towards Jeremy in the expressive setting, thereby changing the context from where Mark is indifferent (\(cu_{1}\)) to one where Mark holds a negative attitude toward Jeremy (\(cu_{2}\))Footnote 8. For Potts, expressives only operate on the expressive setting and do not interact with the descriptive dimension, thus there is no effect on the descriptive content of Attributive.

Potts places one important constraint on admissible contexts which he calls the expressive consistency constraint (Potts 2007b, p. 179). A context is only admissible if the expressive setting only contains one attitude of the judge towards some entity or situation. This constraint outlaws a context in which a judge has both negative and positive feelings towards some entity. Taking Attributive, we cannot have one cu where Mark feels both positively and negatively towards Jeremy. When discussing example Attributive, we saw that introduction of f**khead changed the context from \(cu_{1}\) to \(cu_{2}\), this is in line with the expressive consistency constraint for both attitudes are not held at the same context.

What follows from this is that we can give a straightforward explanation of what examples like Attributive mean, represented below:

The expressive content is independently captured from the descriptive content. We capture the negative attitude of the judge of the context of utterance \(cu_{j}\) (in this case Mark) towards some entity (Jeremy).

3 Expressives and Independence

It’s clear from the section above how Potts deals with expressives that do not seem to contribute to the truth-conditional content. It thus, seems reasonable to say that expressives (at least in this particular syntactic position) really do possess the property of independence as they reside in a different dimension to truth-conditional content.

What is quite surprising, however, is the treatment that is suggested of exactly the same word when it occurs in a predicative construction. Recall our example Predicative from the introduction:

-

Predicative: Jeremy is a f**khead!

The word f**khead seemingly is contributing to the truth-conditional content. If we take the two tests we ran when considering the independence property we see that f**khead in Predicative does not (so to speak) pass those tests. The first was the removal of the expressive to see whether it changes the truth-conditional content. Removing f**khead from Predicative leaves the sentence incomplete:

We also see, that direct denial is possible:

When the expressive occurs in a predicative position, it loses what often is cited as the most distinctive property of expressives, its independence from the descriptive dimension. Although there isn’t a prolonged discussion of expressives in predicative positions in Potts, he is very explicit over what he thinks of cases like Predicative. Potts claims that “[a]ll predicates that appear in copular [/predicative] position must necessarily fail to be expressive"(2007b, p. 194). As such, it seems the word f**khead is highly sensitive to the syntactic position in which it occurs: whilst f**khead in Attributive would be given a completely expressive treatment, the same word would be given (only) a descriptive treatment in Predicative.

This solution to our puzzle does not seem to be satisfactory, not because we treat the expressive occurring in predicative positions as descriptive, but because Potts attempts to remove any expressivity from the predicate. By claiming that the expressive in predicative position fails to have any expressive element, one fails to explain the fact that the word f**khead (regardless of what position it occurs in) communicates Mark’s negative attitude towards Jeremy. Furthermore, the word f**khead when in predicative position still shares properties with the lexeme in attributive position. Zimmermann (2007, p. 249) notes that even when expressives occur in a predicative position they still exhibit the properties of descriptive ineffability and perspective dependence. We will focus on these particular properties in Sect. 3.2.

The next issue with Potts’ treatment of examples like Predicative, is that it can be conceived as an ad hoc stipulation that only follows from the semantics sketched out in Sect. 2, rather than the linguistic data available. Particularly it is the independence property that prevents expressives in predicative positions from carrying any expressive content. If we consider how people use expressives, it is very common to see these words in predicative positions and agents seem to communicate not only truth-conditional content but also their attitudes.

3.1 Expressive and descriptive content

In this section, I look at some linguistic data where the expressive seems to contribute to both dimensions. If we accept that an expressive item can contribute to both dimensions then this will give us good reason to reject the independence property as a crucial aspect of expressives and look for a semantic account which incorporates both expressive and descriptive dimensions. Firstly, let’s consider the following example where we may take an expressive to be a modifier, where the modified item is a descriptive one:

In (10), the expressive f**king modifies brilliant, which Geurts takes to (descriptively) mean ‘very brilliant’ or ‘very very brilliant’ (2007, p. 211). If this is the case, then removing the expressive lexeme would affect the truth-conditional content. After all there is a difference between brilliant and very brilliant. This suggests that the expressive seems to be descriptive in some respect. Furthermore we still get the speaker portraying a certain attitude with the use of f**king (depending on the context it can be either positive or negative). Again there would be a difference in saying that something is very brilliant and f**king brilliant.

Further linguistic data which appears to support the claim that expressives contribute to both descriptive and expressive content can be found in languages that utilise a honorific system. One such example present in Japanese is discussed by McCready (2010):

Here the verb irassharu (come[Honored]), conveys both descriptive and expressive content. It communicates that the teacher has come and that the teacher is being honored. Furthermore, as noted by McCready (2010, p. 17), these two contents cannot be separated, that is you cannot remove the expressive or the descriptive content from irassharu. Removing irassharu from the sentence would remove both contents - that the teacher came and that the teacher is being honoured. Thus honorifics seem to be a good example of an expressive which cannot be divorced from its descriptive content, yet manages to communicate the expressive content as well.

So far, we have considered how option (i), pure Expressivist Semantics, deals with the word f**khead in different syntactic constructions. We saw that our examples Attributive and Predicative would receive very different treatments. This did not seem like a satisfactory solution for it failed to explain the relationship between the word f**khead in both uses. We also saw that there is linguistic data available that goes against the independence property. Assuming that we allow the expressives in (10) and (11) to contribute to both expressive and descriptive dimensions then there’s little reason to say that f**khead only contributes to the descriptive dimension. As such, we can move away from the idea that expressive content is completely independent from descriptive content. In what follows, I propose that the more distinguishing features of expressives are their perspective dependence and descriptive ineffability. It is these two properties that make expressives special.

3.2 What’s so special about expressives?

Having doubted the independence property, we may rethink whether expressives do really possess the status of being different to ordinary descriptive words. Geurts, for example, doubts whether there is anything more special to expressives than ordinary words:

I disagree with Geurts that expressives are just like perfectly ordinary lexemes, for they always carry with them two properties which are distinctive to expressives: perspective dependence and descriptive ineffability.

Perspective dependence is rather straightforward. We saw how unlike ordinary words, to get the meaning of an expressive we must introduce the judge parameter into the context of utterance. That certain expressions are context dependent is of no surprise. For example, the indexical word ‘I’, is dependent on the agent parameter in the context of utterance to gain its content. What is distinctive about expressives, however, is that in virtue of having a judge parameter we get the content from a certain point of view. The expressive tells us something about the judge - the judge’s attitude. This is different from an indexical ‘I’ for the agent parameter merely picks out the referent of the utterance, rather than telling us anything about the judge’s point of view or their mental state.

Descriptive ineffability on the other hand is more contentious. Seemingly, it is apparent that replacing an expressive word with one which is meant to be wholly descriptive does leave out something important, for example:Footnote 9

If we equate example (12a) with (12b) then it seems that we are missing out on the expressive punchFootnote 10 that the word asshole carries with it. We will miss out on the highly negative attitude that the word asshole has and that the word obnoxious seems to be missing.

One might argue at this point that there are some ordinary words that also lack a sufficient descriptive paraphrase. There are purely descriptive words which seem to exhibit ineffability, thus we cannot claim that the special property of expressives is ineffability. This is precisely the argument that Geurts makes:

Descriptive ineffability in respect to expressives as discussed in Sect. 2, means that “[s]peakers are never fully satisfied when they paraphrase expressive content using descriptive, i.e., nonexpressive, terms" (Potts 2007b, p. 166). If we consider it as a property of descriptive content, then we may say that the speakers are unsatisfied with a paraphrase of one descriptive content into another. Bearing this in mind there are several points to note about the quote above. Firstly, it appears that some of the words mentioned do seem to have a pretty good descriptive paraphrase. For example: the may be defined “as a function with domain the set of sets with exactly one element" (Barwise and Cooper 1981, p. 166)Footnote 11; because as in ‘a because b’ may be defined as ‘b is the reason a happened’; green may be defined as a colour that is between blue and yellow or it could be given a more formal definition in terms of wavelength intervalFootnote 12.

Geurts’ point can still stand given that there could be multiple suitable paraphrases to a word and we can pick one depending on the context. This however, I see as a point about polysemy rather than descriptive ineffability. The reason why there isn’t simply one suitable paraphrase for words aforementioned is that they can have multiple meanings, normally determined by a context. Take the word green again, in a context where I am trying explain to a child what green means, it could be sufficient to say ‘it’s the colour between blue and yellow’; in a context where I’m carrying out some scientific experiment I might want to adopt the definition of ‘it’s the colour with the wavelength interval between 500–570 nanometers’. The case is different with expressives, for no matter what context we are in we cannot give a sufficient descriptive paraphrase for the expressive. If we are to agree that asshole has the descriptive meaning of obnoxious [as in cases (12a) and (12b)], we would still be missing that crucial ingredient that makes expressives expressive. We would be missing the expressive punch which conveys the judge’s attitude. Putting the expressive in purely descriptive terms fails to convey this and this is precisely the reason why they cannot receive a satisfatory descriptive paraphrase.

4 Gutzmann’s expressive-contextualism

The trouble with Potts’ account is that it’s too restrictive as it can only deal with expressives which do not contribute to the descriptive dimension. What is needed to account for examples like Predicative is a theory that allows for the expressive and the descriptive dimensions to co-exist, some sort of hybrid account. Such an account is presented by Gutzmann (2015, 2016)Footnote 13 who utilises the foundations laid by Kaplan (1999) in his exploration of non-truth-conditional meaning.

The rough idea behind Gutzmann’s expressive semantics is that just like ordinary descriptive utterances have truth-conditions under which the proposition is either true or false, expressive utterances have use-conditions under which the utterance is felicitous or infelicitous. Take the following examples:

In (13a) what would make the utterance true is that in the world w the turkey is in the fridge. If in w the turkey is not in the fridge then the utterance fails to meet the truth-conditions and thus would be false. When it comes to expressive items we talk about conditions under which the expressive is felicitous. We consider the questions—‘What conditions must be meant so that the expressive is felicitously used?’. We say that (13b) is felicitously uttered just in case the judge of the context of (13b) has observed a minor mishap in the world of that contextFootnote 14.

In Gutzmann’s hybrid semantics each dimension can be accounted for by using both truth-conditions and use-conditions. If this is the case, then we do not need to deny that f**khead in Predicative fails to carry an expressive element, but rather that this expressive element can be fleshed out in terms of the conditions under which the expressive is felicitously used. Gutzmann (2015) does not seem to focus on the cases like Predicative:

-

Predicative: Jeremy is a f**khead.

He does, however, focus on constructions which appear similar to Predicative, for example ethnic slursFootnote 15:

Here the slur honky is supposed to communicate two things: (i) Jeremy is white and, (ii) the speaker has a negative attitude towards white people. Thus we can say that (14) is true just in case Jeremy is white (truth-conditions) and felicitously used just in case the speaker has a negative attitude towards white people (use-conditions)Footnote 16.

Ethnic slurs and expressive epithets like f**khead differ in two important ways. Firstly, slurs are what Gutzmann calls isolated expressive items as they do not take a particular argument in the construction: the negative attitude is not aimed at Jeremy by the use of honky, but white people in general. As such the argument (in (14)) passes onto the truth-conditional level untouched by the expressive dimension. F**khead, on the other hand, takes Jeremy as its argument and the negative attitude is directed only at him (rather than people or Jeremys in general), Gutzmann calls these functional expressive items (2015, p. 39).

Secondly, the truth-conditions are much more clearly known in cases like (14) than in Predicative. This is because honky appears to have an attitude neutral counterpart (white/Caucasian) whereas the closest we can come with f**khead is a contemptible person. This is because the expressive f**khead does not pick out a particular group, but rather a particular subject.

Gutzmann only briefly mentions cases like Predicative, with the example:

Interestingly, this example is being treated as a shunting expressive item. Shunting is a term applied to “those semantic objects that ‘shunt’ information from one dimension to another, without leaving anything behind for further modification" (McCready 2010, 18). In other words, the expressive object will take with it all the information to the expressive dimension without leaving any descriptive content to be evaluated for truth, resulting only in expressive content. Consider how-exclamatives:

In (16), every word is descriptive but no descriptive content is produced, rather (16) communicates the expressive content of the speaker being surprised by Michael’s height. The expressive construction moves or ‘shunts’ the information conveyed by (16) to the expressive dimension without leaving anything behind to be evaluated for truth.

It appears that this is what Gutzmann wants to say about Predicative. The expressive f**khead, shunts all the information to the expressive dimension not leaving anything substantial to be evaluated at the descriptive dimension. Gutzmann claims that examples like (15) “only give back trivial truth-conditional content” (2015, p. 270), which means that nothing meaningful is communicated in the descriptive dimension.

Prima facie, this explanation is better than the one provided by Potts. Gutzmann is allowing the expressive f**khead to contribute to the expressive dimension. As such, we can at least explain the relationship between the occurrence of f**khead in Predicative and Attributive—both occurrences carry expressive content. However, we are still left with some pressing questions to be answered, such as how are we able to have what seem to be meaningful (although subjective) disagreements or denials involving cases like Predicative? For example:

If f**khead failed to contribute anything meaningful to the descriptive dimension, then it would seem odd that Dobby could disagree with Mark and negate his utterance. It seems however that (17b) is completely felicitous and communicates something non-trivial namely that Dobby does not believe Jeremy to be a f**khead.

Because of this I reject Gutzmann’s claim that examples like Predicative lack any meaningful descriptive content. If the reasoning above is correct and f**khead in Predicative does carry meaningful descriptive content, we need to consider which semantic theory can best account for the descriptive content, as well as, the expressive content.

Gutzmann’s project in (2015) does not seem to be to explore which descriptive semantic approach can best capture the nature of expressives, but rather to find a formal framework which allows for both descriptive and expressive dimensions to meaningfully contribute to the overall meaning of a sentence. Consequently, there is no consideration of the merits of different descriptive approaches (Contextualism vs Relativism, for example). However, there is discussion of this kind in Gutzmann (2016) which will be the focus for the remainder of this section.

Gutzmann suggests a hybrid semantics for the treatment of predicates of personal taste (words like tasty and fun). The idea is to combine Expressivist semantics with Contextualist semantics in order to fully capture the meaning of the predicate - I will refer to such a view as Expressive-ContextualismFootnote 17. The Contextualist semantics posits a covert indexical element that is present in the meaning of a predicate of personal taste. This means that Gutzmann is making use out of the judge of the context of utterance (\(cu_{j}\)) when accounting for the descriptive content. Whoever the judge picks out will feature in the content of the proposition.

Thus we can spell out the truth conditions in the following manner:

-

‘Turkey is tasty’ is true in a context c and world w iff the \(cu_j\) likes turkey in w.

To account for the expressive dimension we need to look at the use-conditions of tasty. Gutzmann’s (2016, pp. 39–40) account relies on the idea that predicates of personal taste carry a normative component about what should count as tasty (or fun, etc.). As such use-conditions of expressives are tied with this normative character:

He further ties the felicity conditions to the truth-conditional content, with the reasoning that this normative content of a predicate of personal taste is dependent on truth-conditional content being asserted (Gutzmann 2016, p. 43). The final product results in a biconditional:

This complex attempt at capturing truth-conditions and use-conditions was needed in order to account for disagreements involving predicates of personal tastes. I will have some discussion of my preferred way of capturing the expressive content in the next section, but for now we’ll follow Gutzmann’s explication.

Examples including predicates tasty and fun are very similar to our example in Predicative. They both seem to be subjective in a similar manner: there are no objective properties in the world corresponding to tasty or f**khead. It seems that it is down to the judge to class something as tasty or a f**khead. Unlike ethnic slurs, predicates of personal taste do not have truth-conditions which depend on some objective property. Recall in example (14), we took the truth-conditions of the expressive honky to be associated with ‘a white person’. Truth-conditions for tasty, however, are completely subjective and agent dependent “‘Tofu is tasty’ is true in context c and world w if the judge of c likes tofu in w” (Gutzmann 2016, p. 40, original emphasis). Because of the considerations above it is reasonable to allow the same treatment for the expressive f**khead as is given to tasty.

If we are to allow an Expressive-Contextualist treatment of examples like Predicative, then we would get the following truth-conditions and use-conditions:

My critique against Gutzmann’s account concerns positing a covert indexical element in the descriptive content of a predicate of personal tasteFootnote 18. On a closer inspection it appears the indexical element that is supposed to be there is quite tricky to locate. Köbel (2004, pp. 303–304), for example, notes that if the indexical element is present in predicates of personal taste then the following construction should be infelicitous and contradictory:

However, Mark’s utterance in (22) is not only grammatical, it’s also felicitous. We can further expand on Kölbel example by imagining a disagreement between between Mark and Jeremy:

Since the indexical element is present in (23a), the descriptive content should be equivalent to that in (23c). Consequently, (23c) should come across as repetitive and redundant. This however is not the intuition. We see that (23c) is not a repetition of (23a) and in fact communicates new semantic information.

A possible response on behalf of Contextualism may be that in (23a) it’s unclear who exactly the judge is, as the turkey could be tasty to the speaker, to the group, generally speaking, etc. When Mark utters (23c) he makes it clear that the covert indexical element is picking him out.

This response it not completely satisfactory, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, although exocentric judges (i.e. judges other than the speaker) do occur with predicates of personal taste, just as they occur with expressives, they are not the default position. It should be clear from the context that the judge is taken to be someone else than the speaker, otherwise we can assume an autocentric perspective (where the speaker is the judge). If this is correct, then it seems odd that Mark would need to clarify that he’s talking about himself. Secondly, we can reconstruct the example where it is clear that Mark is taking an autocentric perspective, yet an utterance like (23c) still appears to add new semantic information.

We see in (24a) that Mark is removing the possibility that the reading ought to be taken as to everyone or to the group, etc. It’s clear that ‘turkey is tasty’ should be taken from Marks perspective. If this is the case, then the descriptive content of ‘turkey is tasty’ in (24a) ought to be the same as in (24c). We see however, that (24c) adds new semantic content to the conversation, therefore it is difficult to accept that the indexical element is covertly present in sentences like (23a) and (24a).

I am going to make a similar argument regarding the apparent indexical element present in the expressive occurring in a predicative position. Note that I will be diverging from using Predicative, for the word f**khead appears to take on a different sense when an explicit indexical reference is introduced. Take Mark to utter:

The sense in which Mark is using the word f**khead is a relational one, to mean that Jeremy is acting mean, nasty, selfish, etc., towards Mark. This is different from the case we see in Predicative, for there Mark is expressing his negative attitude towards Jeremy without the suggestion that Jeremy is acting negatively towards Mark (although we can make that inference). The issue is that as soon as to me is added where the subject is a being who can perform actions against one, then the relational reading is the first one we get. Because I want to keep the examples similar to those in (22)–(24), I will use an example that takes the preposition for me rather than to me.

Similar argument can be made if we want to claim that the expressive also carries a hidden indexical element. Kölbel type examples like (22) seems to work well here. Take a band called Man Feelings, everyone thinks they’re terrible except Dobby, as such she might utter:

Again, just like with example (22), it seems that Dobby’s utterance is grammatical and felicitous. Which should not be the case if the first occurrence of ‘Man Feelings are shit’ has a hidden indexical element. Again we can expand on this example when we consider Mark and Dobby disagreeing over whether Man Feelings are shit:

As before, the response from the contextualist may be that in (27a) we are not sure of which judge is getting picked out, so Mark is making it clear that it’s him in (27c). As in (24) we can expand on this example.

To say that shit in (28a) has a hidden indexical is to say that it essentially communicates the proposition expressed by (28c). However, in (28c), new propositional information seems to be communicated which we should not expect if it was already present in (28a).

Gutzmann’s way of combining expressive elements with descriptive semantics looks very promising. The issue, however, is which descriptive theory to add in order to successfully capture the truth-conditional content of expressives in predicative positions. Contextualism as presented in Gutzmann (2016) is not satisfactory for the reasons outlined above. Therefore, we have a motive to look for an alternative descriptive account. This is the focus of the next section.

5 Expressive-relativism and expressives in predicative positions

We started this paper with two examples:

-

Attributive: That f**khead Jeremy forgot the turkey.

-

Predicative: Jeremy is a f**khead!

We noted that there seems to be little semantic difference between the use of the word f**khead in Predicative and Attributive. However, the puzzle presented itself when in Predicative f**khead appears to contribute to the truth-conditional content, whereas in Attributive the content contributes only to the expressive dimension. The question we have concerned ourselves with is how to account for this fact. Having looked at two good candidates for providing us with an answer and deeming them unsatisfactory, it’s time to consider the last alternative. In what follows, I put forth a hybrid account which combines Expressive semantics with Assessment-Sensitive Relativism, like that presented in Lasersohn (2005, 2017). I call this view Expressive-Relativism.

5.1 Assessment-sensitive relativism

In this section, I will briefly consider Assessment-Sensitive Relativism (henceforth Relativism) and the appropriate amendment of the semantics. The version I focus on is proposed by Lasersohn (2005, 2017) with the intention of accounting for predicates of personal taste, i.e. tasty, fun, etc. The main tenet of Relativism is that the truth-values of certain expressions are sensitive to contexts of assessment and have no influence from the context of utterance. This means that the same propositions will have the same content in each CU, yet can be true at \(ca_{1}\), but false at \(ca_{2}\). Relativism is well suited for subjective language and particularly for predicates of personal taste as it allows one speaker to express p and the other to express \(\mathord {\thicksim }p\), yet both speakers to utter something true. As such, we are able to have what some call faultless disagreements, where two speakers disagree but neither is at fault for expressing a false proposition. For instance:

Because predicates of personal taste are subjective and do not pick out any objective properties in the world, it’s plausible to say that in (29), both Mark and Jeremy have conveyed something true. Relativism accommodates this intuition making use out of the judge parameter in the context of assessment. Instead of merely evaluating a proposition relative to a world and a time we also evaluate it in respect to a judge. Thus, say that (29a) is true relative to a context of assessment where \(ca_{j}\) is Mark and (29b) is true relative to a context of assessment where \(ca_{j}\) is JeremyFootnote 19.

Both Lasersohn and Potts make use out of the judge parameter in their semantics. The big difference between Potts’ use of the judge and Lasersohn’s is that for Potts the judge plays a content determining role. It helps to determine what expressive content is carried by the expressive item. For Lasersohn, on the other hand, the judge only plays a part in the context of assessment, it does not influence the content in any way. The judge parameter helps to determine the truth-values of the propositions. Thus, (29a) will have the same content as uttered by Mark or Jeremy. To see comparison with Gutzmann, just like with Potts, the judge plays the role in the context of utterance—it helps to determine content. Unlike Potts however, the judge not only helps to determine the expressive content, but also the descriptive content. So although the judge parameter does not lend a hand in evaluating the proposition, it is essential in determining the proposition in the first place. Table 1 summarises this neatly.

By including the judge parameter in the CA, Relativism is able to capture the subjective nature of predicates of personal taste in a straightforward manner. It is the judge that retains the subjectivity of these terms and precludes them from being assessed in an objective way. Because of this, Relativism is well suited to combine with Expressivism. As we saw in Sect. 2, it is the judge of the CU that manages to capture the subjectivity of expressive terms. Once expressives take on predicative positions and are forced to contribute to the truth-conditional content, it is important to retain the subjectivity that they possess when they occur in attributive positions. Thus, the judge parameter seems like the best candidate to be able to capture subjectivity in both CU and CA. Essentially what the judge parameter in the CA grants is that when in Predicative the expressive f**khead contributes to the truth-conditional content, hence we can explain how this utterance can be true. It is true relative to some judge who has a negative attitude towards Jeremy. This is parallel to predicates of personal taste, when Mark claims that the property of tasty applies to turkey there is no objective way of telling whether this is true, precisely because predicates of personal taste lack objectivity. Thus tasty as applied to turkey will only be true in instances where the judge likes turkey. In this paper, I am not arguing that predicates of personal taste are expressives or vice versa, I merely want to point out similarities in subjectivity between the two which motivates us to consider Relativism as a suitable approach for the hybrid account.

Notice that Lasersohn’s Relativism corresponds to option (iii) set out in the introduction. The use of f**khead in both Attributive and Predicative would receive a descriptive treatment. If we were to apply Lasersohn’s treatment to Predicative it would face the same criticism as Potts did, namely that it leaves out the all important expressive element that the word carries with it. Without the expressive ‘punch’ it’s not clear how we can give a full meaning of the expressive, or explain how it manages to communicate the judge’s attitudeFootnote 20

5.2 Expressive-relativism

In this last section I outline a hybrid account called Expressive-Relativism. When we have instances like Predicative, we need a theory that deals with both expressive and descriptive dimensions. By combining Relativist and Expressivist semantics we can achieve this goal. Relativism will be used to deal with the descriptive dimension by giving us relativised truth-values:

For the descriptive content I will just keep with ‘Jeremy is a f**khead’ however if the reader feels uneasy about using the predicate in its expressive form they can substitute it for something more neutral like ‘Jeremy is a contemptible person’ paraphrase for Predicative. Bear in mind however that as argued in Sect. 3.2 no descriptive paraphrase can successfully capture the meaning of an expressive as expressives carry with them the property of descriptive ineffabilityFootnote 21. Notice that unlike Expressive-Contextualism, the descriptive content does not contain an indexical element. As such, there is no mention of a judge in the descriptive content of the expressive.

From the Expressivist semantics I propose the expressive content is given in the way we saw with Potts in Sect. 2, where the judge is needed to deliver the expressive content:

I diverge from Gutzmann’s suggestion that the use conditions ought to be ‘Jeremy shall count as a f**khead in cu’. Instead the use-conditions should be explicitly tied to the judge of the context of utterance—as shown in (31b).

The subjective nature of an expressive is reflected in the truth-conditions with the explicit inclusion of the judge in the condition. We want the same for the use-conditions. By including the judge in the use-conditions we will be able to reflect the subjective nature of expressives in the expressive dimension. We will absolutely tie the use of the expressive to the judge having the relevant attitude. By doing so we can make sense of cases where it is clear that the judge is only talking about themselves and their attitudes, for example:

If we take our reformulation of Gutzmann’s use-condition—‘Jeremy shall count as a f**khead in cu.’—then it does not seem like Mark’s utterance (32) ought to be felicitous. Mark is making clear that it’s not just at any CU that Jeremy should be held to be a f**khead, but only from the \(cu_{j}\) where Mark is the judge, as it is only his attitude to be reflected by the utterance and not some other judge’s.

Furthermore, having the use-conditions explicitly tied to a \(cu_{j}\), as in (31b), reflects the perspective dependence property of expressives. Expressives are not evaluated just from some context of utterance, but from a particular perspective in a context of utterance. As such, we should judge whether an expressive is felicitously used in a given CU from a particular perspective.

Expressive-Relativism accounts for the descriptive nature of Predicative via Relativist semantics which utilise the judge parameter in the context of assessment to give relative truth-values. The expressive dimension is given a treatment via Expressivist semantics where the judge plays a key role in determining the expressive content of the predicate. How Expressive-Relativism differs from theories considered so far can be seen in Table 2.

There is a clear link between the judge in the context of utterance and the judge in the context of assessment. In order for the truth-conditions to be true, the expressive has to be felicitously used. We can only say that the judge has contempt for Jeremy if the judge has a negative attitude towards Jeremy. This might seem like a trivial point and in fact it’s encouraging that it is. The triviality helps to support the idea that there is a link between use-conditions and the truth-conditions. It explains that one should not use an expressive which communicates a negative attitude if one does not want to commit oneself to the truth of that proposition. As such, when Mark utters Predicative in virtue of him using that expressive he commits himself only to those contexts of assessment in which Predicative will come out as true. If Mark did not in fact hold a negative attitude towards Jeremy then the proposition expressed would not be true where Mark is the \(ca_{j}\) and the expressive would not be used felicitously. The triviality behind the idea that \(ca_{j}\) having contempt for Jeremy can only be true if the \(cu_{j}\) has a negative attitude towards Jeremy explains why there is such an apparent link between the judge of the context of utterance and the judge of the context of assessment.

I will add a caveat to what I have said above. As noted, when one utters an expressive one commits oneself to certain CAs. Just like when one asserts a non-subjective proposition (e.g. ‘the turkey is in the fridge’), one intends for this to be true in a particular context. Simply by uttering the sentence one commits oneself to the truth of that proposition. Since the use-conditions and truth-conditions are linked together when Mark utters a sentence like Predicative, one might think that Mark commits himself only to that CA in which he has a negative attitude and thus his utterance will only convey something true at the particular CA in which he is the judge. However this is not the case, Mark is not merely committing himself to one CA (i.e. the CA in which he is the judge), but rather a set of CAs in which the judges share the same attitude. This might seem odd, after all it is your attitude that decides in which CA your utterance comes out as true or false. However, intuitively it seems correct that one sentence can be assessed from more than one perspective and thus it can be true or false from more than one perspective. This is backed up with the agreement and disagreement data. Consider the following:

In (33), it seems that Aurora is agreeing with descriptive content that ‘Jeremy is a f**khead’ produces, but she is not agreeing that the proposition is only true as evaluated from the context of assessment in which Mark is the judgeFootnote 22. Rather, Aurora agrees that she too finds the proposition to be true. As such, we have a change in the context of assessment as the judge parameter fixes Aurora as the judge rather than Mark. Because of this we need to be able to accommodate the appropriate attitude matching two different CAs - \(ca_{1}\) where Aurora is the judge and \(ca_{2}\) where Mark is the judge. Thus, a set of CAs in which the proposition ‘Jeremy is a f**khead’ comes out as true will be those CAs in which the judge has a negative attitude towards Jeremy. And in the case of (33), this set will include both \(ca_{1}\) and \(ca_{2}\).

A brief reflection on the disagreement data provides further justification for why an utterance needs to be evaluated at more than one CA. Take the following:

Similarly to the agreement data, when Dobby disagrees she’s not disagreeing that the proposition ‘Jeremy is a f**khead’ is false as evaluated from the CA in which Mark is the judge. Instead she is disagreeing with the proposition expressed by (34), and she is rejecting the claim that the right CA from which (34) ought to be evaluated is that where \(ca_{j}\) has a negative attitude towards Jeremy. Simply put, (34a) will come out as false where the \(ca_{j}\) is Dobby or anyone who does not have a negative attitude towards Jeremy. Unlike with (33) where both Mark and Aurora were part of a set of judges who share a negative attitude toward Jeremy, Dobby is doing quite the opposite. By disagreeing she is being explicit that she is not a member of a set of CAs in which (34a) comes out as true.

By adopting Expressive-Relativism we can explain both descriptive and expressive aspects of f**khead in Predicative. Assessment-Sensitive Relativism can provide us with a way of accounting for the truth-conditions of Predicative. The Expressive semantics explain the expressive aspect of f*ckhead when occurring in predicative position. This provides a straightforward explanation of the similarities between f**khead in Attributive and Predicative can be given. The expressive f**khead in both positions produces expressive content. This expressive content is what can explain the feeling that in both occurrences Mark is labeling Jeremy as a f**khead.

6 Conclusion

We have considered the application of various approaches to explain how the expressive f**khead behaves in predicative constructions such as ‘Jeremy is a f**khead’. We saw that Expressivist semantics by itself was too strict by completely banishing the predicate to the descriptive dimension. We saw that the hybrid account, Expressive-Contextualism, fared better as it allowed the predicate to retain expressivity but there were serious doubts over the suitability of using Contextualist semantics. The option we have settled with, Expressive-Relativism, appears to have plenty of promise in providing a sufficient answer to how f**khead in Predicative behaves. It is also an account with little exploration in the literature which leaves itself open for further research.

Notes

This example is borrowed from a British sitcom Peep Show (2010, Season 7, episode 5). I have simplified the example quite drastically, Mark’s full utterance is: “You what? No turkey? You f**king idiot, Jeremy! You total f**king idiot! That was your job, you f**king moron! You cretin! You’re a f**khead! That’s what you are! A f**king s**thead!".

The examples used throughout this paper have a potent expressive punch. The use of the offensive expressives was made in order to communicate clearly and straightforwardly the negative attitude portrayed by the speaker. This helps to contribute to the strength of the arguments presented.

Along with the three properties discussed in the main text, Potts notes three others. Nondisplaceability: expressives say something about the context of utterance, i.e. the agent’s current attitude towards some entity. Immediacy: expressives achieve their intended content simply by being uttered. Repeatability: repeating an expressive strengthens the expressive content (Potts 2007b, pp. 166–167). These properties do not have much bearing on what I go on to say and thus will not feature in the main text. A reviewer has pointed out that repeatability does not seem to affect the expressive item when in predicative position.

Here I take descriptive content to be one which is directly truth-conditional, i.e. one which contributes to the truth value at the first instance. So although there is much content which is truth-conditional (e.g. semantic presuppositions), such content would not be directly truth-conditional and under this definition would not be classed as descriptive content. In his earlier work, Potts (2005) referred to this content as at -issue content, by using ‘descriptive content’ I am keeping with his later (Potts 2007a, b) terminology.

My discussion of the expressive setting is much more informal that what is presented in Potts (2007b). For Potts, the expressive setting is a set of expressive indices, where an expressive index is a triple of \(\langle a \mathbf{I } b\rangle \), a being the judge, I the interval (I \(\sqsubseteq \) [-1,1]) which measures the intensity and the positive/negative attitude that a holds towards b (Potts 2007b, p. 177). The use of expressive indices allows one for differentiating between different expressives (e.g. calling someone f**khead is typically worse than calling someone a bastard), as well as, capture different intensity of the attitudes (e.g. the different in attitude between calling someone a f**khead and a f**king f**khead). Since the use of the expressive setting is much less demanding for this paper, I omit the formal presentation.

In my exposition of the situation I chose the subject of Mark’s anger to be Jeremy, however one could also construct this example as Mark being angered by the situation i.e. Jeremy forgetting the turkey. Nothing rests on this for my purposes. However, see (Zimmermann 2007, pp. 250–252) for a suggestion that attitudes can be aimed at not only to individuals, objects and situations, but to also properties.

The term ‘expressive punch’ is taken from (Lasersohn 2017, p. 233)

For a more formal definition and discussion of the logic of generalised quantifiers see Barwise and Cooper (1981).

I will not try to define every example Geurts has given. I do want to highlight, however, that subjective words like pretty can be classed as predicates of personal taste which under some approaches count as (at least in some sense) expressive, see for example Gutzmann (2016).

Gutzmann’s project in (2015) is to provide a formal framework in which we can allow for an expression to contribute to both the expressive dimension and the descriptive dimension (or use-conditional and truth-conditional in Gutzmann’s terminology). The logic put forth by Gutzmann (which he calls \({\mathcal {L}}_{\text {TU}}\)) develops on the Potts’ (2005) logic (\({\mathcal {L}}_{\text {CI}}\)) and McCready’s (2010) modification of Potts’ system which she calls \({\mathcal {L}}_{\text {CI}}^{+}\). Gutzmann develops new types and compositional rules for \({\mathcal {L}}_{\text {TU}}\) (Gutzmann 2015, see especially pp. 106–107 and pp. 117-125). Gutzmann’s system is admirable, but the complexity and intracity of it goes beyond the scope of this paper. As such I will give an informal discussion drawing from both the material in the book (Gutzmann 2015) as well as the less formal representation given in Gutzmann (2016).

The use-conditions for Oops are taken from (Kaplan 1999, p. 12).

I am not proposing that the account presented in this paper should be or will be applied to slurs (ethnic, gendered, etc.). The literature on slurs is vast and cannot be done justice here, for discussion of slurs see: Cepollaro (2020), Jeshion (2013a, 2013b), Nunberg (2018), Popa-Wyatt and Wyatt (2018), Scott and Stevens (2019), Sosa (2018), Cepollaro and Zeman (2020).

Note that felicitously used does not mean that the speaker is doing something correct/is not blameworthy for using a racial slur. It just means that one should not use this term if one do not have a negative attitude towards whatever group the term picks out.

This is not a term used by Gutzmann, I introduce it for ease of reference.

This argument in respect to predicates of personal taste is presented in Berškytė (2021, pp. 337–338).

Note that we are not merely including an agent/speaker parameter but a judge parameter. This is for similar reasons to Potts’ expressive semantics, that is the agent evaluating the proposition may be someone other than the speaker.

For a full discussion of why standard descriptive versions of Relativism should not be adopted as an account of expressives see Berškytė and Stevens (2019).

One might think it’s possible to think that someone is a f**khead and have no contempt for them. There are at least couple of ways in which this may happen. Firstly, one might be using the expressive in a positive way/figurative way [similar to the use of bastard in (5)]. The second way in which this may happen is if the judge is evaluating the entity in two different respects. Take Mark to utter: “Jeremy is a f**khead, but I still like him”. Mark may hold a negative attitude towards Jeremy in one respect (which then justifies them calling him a f**khead), but still like Jeremy in a different respect. In such an instance we can make the truth-conditions of (30b) more precise with something like ‘True just in case \(ca_{j}\) has contempt for Jeremy in respect of x’. The examples I present in this paper were not intended to be so fine grained, however if the reader feels like the more precise truth-conditions are needed, they’re the welcome to substitute (30b) with the conditions just given.

This does not mean that it is impossible for Aurora to agree with Mark that Jeremy is a f**khead as evaluated from Mark’s perspective, but this would have to be made clear from the context. Aurora may make it clear by saying ‘Yes I can see why you think he is a f**khead’. This, however, is a very different situation where from the one in (33).

References

Barwise, J., & Cooper, R. (1981). Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy, 4(2), 159–219.

Berškytė, J. (2021). Rollercoasters are not fun for mary: Against indexical contextualism. Axiomathes, 31, 315–340.

Berškytė, J., & Stevens, G. (2019). Semantic relativism, expressives, and derogatory epithets. Inquiry, 2019, 1–21.

Cepollaro, B. (2020). Slurs and thick terms: When language encodes values. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Cepollaro, B., & Zeman, D. (2020). Editors’ introduction: The challenge from non-derogatory uses of slurs. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 97(1), 1–10.

Geach, P. T. (1960). Ascriptivism. Philosophical Review, 69(2), 221–225.

Geach, P. T. (1965). Assertion. Philosophical Review, 74(4), 449–465.

Geurts, B. (2007). Really fucking brilliant. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 209–214.

Gutzmann, D. (2015). Use-conditional meaning: Studies in multidimensional semantics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Gutzmann, D. (2016). If expressivism is fun, go for it. In C. Meier & J. van Wijnberger-Huitink (Eds.), Subjective meaning: Alternatives to relativism (pp. 21–46). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Jeshion, R. (2013a). Expressivism and the offensiveness of slurs. Philosophical Perspectives, 27(1), 231–259.

Jeshion, R. (2013b). Slurs and stereotypes. Analytic Philosophy, 54(3), 314–329.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives: An essay on the semantics, logic, metaphysics, and epistemology of demonstratives and other indexicals (pp. 481–563). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, D. (1999). The meaning of Ouch and Oops: Explorations in the theory of meaning as use. UCLA, manuscript.

Kölbel, M. (2004). Indexical relativism versus genuine relativism. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 3(12), 297–313.

Kratzer, A. (1999). Beyond ‘Ouch’ and ‘Oops’: How descriptive and expressive meanings interact. Paper presented at the Cornell conference on theories of context dependency. Hand out available: https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/WEwNGUyO/Beyond%20%22Ouch%22%20and%20%22Oops%22.pdf

Lasersohn, P. (2005). Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28(6), 643–686.

Lasersohn, P. (2007). Expressives, perspective and presupposition. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 223–230.

Lasersohn, P. (2017). Subjectivity and perspective in truth-theoretic semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCready, E. (2010). Varieties of conventional implicature. Semantics and Pragmatics, 3(8), 1–57.

Nunberg, G. (2018). The social life of slurs. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press.

Peep Show, (2010). Season 7, Episode 5. Channel 4.

Popa-Wyatt, M., & Wyatt, J. L. (2018). Slurs, roles and power. Philosophical Studies, 175(11), 2879–2906.

Potts, C. (2005). The logic of conventional implicatures., Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Potts, C. (2007a). The centrality of expressive indices. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 255–268.

Potts, C. (2007b). The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 165–198.

Scott, M., & Stevens, G. (2019). An indexical theory of racial pejoratives. Analytic Philosophy, 60(4), 385–404.

Sosa, D. (2018). Bad words: Philosophical perspectives on slurs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stevenson, C. L. (1937). The emotive meaning of ethical terms. Mind, 46(181), 14–31.

Zimmermann, M. (2007). I like that damn paper—Three comments on Christopher Potts’ The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 247–254.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their helpful comments and suggestions. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Philosophy Department at University of Manchester, I would like to thank the audience for their useful input. I thank Andrew Koontz-Garboden, Chris Daly and Jeroen Smid for giving up their time on this topic. Lastly, I thank Graham Stevens for his detailed and insightful discussions on this paper and subject.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berškytė, J. Jeremy is a... Expressive-relativism and expressives in predicative positions. Synthese 199, 12517–12539 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03341-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03341-y