Abstract

For Knox, ‘spacetime’ is to be defined functionally, as that which picks out a structure of local inertial frames. Assuming that Knox is motivated to construct this functional definition of spacetime on the grounds that it appears to identify that structure which plays the operational role of spacetime—i.e., that structure which is actually surveyed by physical rods and clocks built from matter fields—we identify in this paper important limitations of her approach: these limitations are based upon the fact that there is a gap between inertial frame structure and that which is operationally significant in the above sense. We present five concrete cases in which these two notions come apart, before considering various ways in which Knox’s spacetime functionalism might be amended in light of these issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The attempt to lift all of geometry out of the murky sphere of the empirical now led imperceptibly to a mental reorientation that is somewhat analogous to the promotion of revered heroes of antiquity to gods.—(Einstein 2015, pp. 16–17)

The view that spacetime just is a Lorentizan manifold \(\langle M, g_{ab} \rangle \) is no longer in vogue. Rather, in recent times philosophers have espoused a more nuanced approach to spacetime—Lam and Wüthrich put the idea succinctly, when they state that “spacetime is as spacetime does” (Lam and Wüthrich 2018). The idea is not to primitively identify some object in the mathematics of one’s theories as being spatiotemporal, but rather to identify the structures in one’s theories which play a certain, antecedently-specified functional role of spacetime. This approach to spacetime is now known as spacetime functionalism.

One of the best-known functional approaches to spacetime is due to Eleanor Knox, who states the following: (Knox 2011, p. 9)

I propose that the spacetime role is played by whatever defines a structure of local inertial frames.

Call this approach inertial frame spacetime functionalism. Knox motivates her brand of functionalism by appeal to Harvey Brown’s views on the operational significance of putatively spatiotemporal structures in our theories of physics (see Knox 2011). In particular (as we read her), she takes it that spacetime just is that structure which is surveyed by physical rods and clocks, built from matter fields. That such a reading is reasonable is evident in passages such as the following (and her ensuing endorsement of the content thereof):

Much of Brown’s work is directly relevant to the question of defining a role for spacetime structure. In particular, two key themes emerge from his book [Physical Relativity (Brown 2005)] that can serve as desiderata when seeking a concise way of expressing the spacetime role. First, Brown is concerned with the operational significance of the spacetime metric; the spacetime role had better ensure that the behaviour of rods, clocks, light rays and test particles appropriately (if not exactly) reflects the metric structure. Second, and related, he notes that ensuring such operational significance is a matter of dynamics. (Knox 2011, p. 5)

As we will discuss in more detail below, the implicit motivation for inertial frame spacetime functionalism is that it identifies structure which satisfies these criteria.

It is, however, on exactly this front that in the present paper we identify Knox’s programme as lacking. We do so by demonstrating that the structure which “defines a structure of local inertial frames”—what we dub theoretical spacetime—need not coincide with that structure which is actually surveyed by physical rods and clocks built from matter fields—what we dub operational spacetime. In addition, in this paper we seek to clarify other matters—for example, the connections between Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism, and the dynamical approach to spacetime theories, developed in Brown (2005), Brown and Pooley (2001, 2006).

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, we present Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism. In Sect. 3, we draw the above-mentioned distinction between theoretical and operational spacetime. In Sect. 4, we present five cases in which theoretical spacetime comes apart from operational spacetime—while it turns out that Knox has the resources to argue that one of these five cases is unproblematic, the remaining four do seem to pose genuine problems for Knox’s account (on the above reading). In Sect. 5, we consider means via which Knox might revise her spacetime functionalist approach, in order to overcome the gap between theoretical and operational spacetime. In Sect. 6, we compare Knox’s spacetime functionalist approach with a different spacetime functionalist view, due to Baker (2018a). In Sect. 7, we consider how inertial frame spacetime functionalism relates to the dynamical and geometrical approaches to spacetime theories.

2 Spacetime functionalism

There is a range of motivations that one might have for embracing a functionalist approach to spacetime.Footnote 1 For example, one might be concerned with the semantic project of giving a systematic account of the usage of the term ‘spacetime’. Alternatively, one might be interested in identifying some significant universal properties of dynamical systems that allows one to abstract away from particular intrinsic features of the systems under consideration (such as their microphysical composition), and to make generic claims about the behaviour of those systems.Footnote 2 It is this latter motivation which we impute to Knox—a reading made plausible by passages such as the following:

[M]y argument here is more concerned with the identification of empirical or phenomenological spacetime geometry, that is the geometrical structure that is reflected by our measuring instruments, operationalized coordinate systems and the like. (Knox 2013, p. 347)

For Knox, ‘spacetime’ should be associated with this codifying structure. The slogan of her own brand of spacetime functionalism—inertial frame spacetime functionalism—is the following: “the spacetime role is played by whatever defines a structure of local inertial frames” (Knox 2011, p. 9). The idea is to functionally define ‘spacetime’ as any structure which itself picks out a structure of local inertial frames—the thought being that, in turn, it is this structure which can play the above-mentioned codifying role:

[C]onsidering the inertial structure provides a shortcut that allows us to glean the empirical consequences of a theory without going into the messy details of our various measuring devices. (Knox 2013, p. 347)

Now, of course, if Knox’s proposal is to have content, the meaning of an ‘inertial frame’ must be articulated. Knox gives the following (itself functional) characterisation of inertial frames:

In Newtonian theories, and in special relativity, inertial frames have at least the following three features:

- 1.

Inertial frames are frames with respect to which force free bodies move with constant velocities.

- 2.

The laws of physics take the same form (a particularly simple one) in all inertial frames.

- 3.

All bodies and physical laws pick out the same equivalence class of inertial frames (universality). (Knox 2013, p. 348)

Any structure which picks out a “structure of local inertial frames”, i.e. a structure of local frames which satisfy these properties (initially identified as significant in the Newtonian/special relativistic context) qualifies, for Knox, as ‘spacetime’.

It is illustrative to consider what Knox has in mind here in the particular, well-known case of general relativity. In order to do so, one further piece of machinery needs to be introduced: the foundational principle known as the strong equivalence principle (SEP). Here is how Knox puts the SEP:Footnote 3

To any required degree of approximation, given a sufficiently small region of spacetime, it is possible to find a reference frame with respect to whose associated coordinates the metric field takes Minkowskian form, and the connection and its derivatives do not appear in any of the fundamental field equations of matter. (Knox 2013, p. 352)

In general relativity, satisfaction of the SEP guarantees that the metric field qualify as spatiotemporal, in Knox’s sense. The reason is that, locally, the symmetries of the dynamical metric field coincide with those of the dynamical equations governing all of the matter fields; in any frame in which these dynamical equations take their simplest form, the metric field itself takes the form \(\mathrm {diag}\left( -1,1,1,1\right) \). (In this paper, following e.g. (Pooley 2013, Section 3.1), we take dynamical symmetries to be those transformations which leave invariant the form of the dynamical equations in the theory under consideration, and we take metric symmetries to be transformations which leave invariant the metric field under consideration.) Thus, the metric field picks out a structure of local inertial frames for all of the matter fields, and so qualifies as spatiotemporal.Footnote 4 This verdict seems correct, insofar as one thinks that it is the metric field \(g_{ab}\) of general relativity which codifies important aspects of the dynamics—e.g., intervals of distance and proper time as read off by physical rods and clocks built from matter fields.

At this point, however, one might ask the following question: how is it that in general such inertial frame structure captures—without recourse to the details—dynamical facts? It is clear that inertial frame structure does capture the common symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields. However, there certainly remains a conceptual gap to be bridged between such symmetries, and the full dynamics of matter, in particular the behaviour of physical systems built from matter fields. In this paper, we argue that the prima facie success of Knox’s programme is a consequence of contingent facts about the relationship between symmetries and full dynamics. When this relationship breaks down, we discover that Knox’s prescription falters in its attempt to pick out an operationally significant structure.Footnote 5

3 Theoretical and operational spacetime

In this section, we argue that Knox’s prescription correctly identifies a structure which we refer to as theoretical spacetime. But the promise of determining an operationally significant structure—i.e., one which is surveyed by physical measurement apparatuses such as rods and clocks—is achieved only via the identification of a (possibly) different structure—one which we refer to as operational spacetime. Knox’s prescription does not invariably deliver operational spacetime.

We begin, in Sect. 3.1, by introducing the concept of theoretical spacetime. In Sect. 3.2, we discuss the distinct notion of operational spacetime. This sets up the discussion in Sect. 4, in which we present five cases in which theoretical spacetime comes apart from operational spacetime.

3.1 Theoretical spacetime

If (local) dynamical symmetries coincide with (local) symmetries of a given metric field,Footnote 6 then we say that that metric field qualifies as theoretical spacetime. However, within this notion of theoretical spacetime, a more fine-grained distinction is possible:

-

1.

Symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime That geometrical structure the (local) symmetries of which coincide with the (local) symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields, up to the invariant quantities associated with these transformations.

-

2.

Cone-coincident theoretical spacetime That geometrical structure the (local) symmetries of which coincide with the (local) symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields, and which (where applicable) agrees on the invariant quantities associated with those dynamical symmetries.Footnote 7

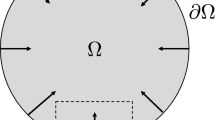

In the case of symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime, although the symmetries of the geometrical structure under consideration coincide (modulo a choice of parameter value of the invariant quantity, call it cFootnote 8) with the (antecedently-coincident) symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields, the associated inertial frames need not coincide. Here is another way to put the issue. Consider two Lorentzian metrics \(\eta _{ab}\) and \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\), related by

for a particular, suitable choice of 1-form \(\xi _a\). The addition of the second term alters the shape of the cone structures associated with \(\eta _{ab}\) versus \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\)—thus, the situation is as in Fig. 1, in which (say) \(\eta _{ab}\) is associated with the outer (blue) cones, and \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\) with the inner (red) cones. In turn, one can demonstrate that the isometries of \(\eta _{ab}\) correspond to Lorentz transformations with one particular invariant speed, and the isometries of \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\) correspond to Lorentz transformations with a different invariant speed. It follows that the frames in which \(\eta _{ab}\) takes its diagonal form are different to the frames in which \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\) takes its diagonal form—the former are related by the first class of Lorentz transformations, the latter by the second.Footnote 9

Now consider a situation in which the fundamental metric field in one’s theory is \(\eta _{ab}\), but the metric field to which the matter fields are coupled in their dynamical equations is \(\tilde{\eta }_{ab}\). In such a case, \(\eta _{ab}\) would qualify as symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime (for both it and the dynamical equations governing matter fields have Lorentz transformations with distinct invariant speed parameters as their symmetries), but not cone-coincident theoretical spacetime (for the specific Lorentz transformations which are symmetries of these objects are different—they feature different invariant speeds).

3.2 Operational spacetime

Cone-coincidence is a stronger condition than symmetry-coincidence. Anticipating, however, that cone-coincidence between a given geometrical structure (viz., a Lorentzian metric field) and the metric field codifying the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields might nevertheless not be sufficient for that geometrical structure to be surveyed by physical measuring apparatuses built from matter fields, we introduce at this juncture a third species of spacetime, which we dub operational spacetime:

-

3.

Operational spacetime That geometrical structure which is correctly surveyed by appropriate configurations of all dynamical fields.

Appropriate configurations of dynamical fields (in particular, rods and clocks—i.e., measurement devices with putative sensitivity to metric and affine structure) ‘correctly survey’ a metric just in case they (approximately) correctly read off intervals of distance, or of proper time along their worldlines, as given by that metric field.

As we read her, Knox’s motivation in advancing her inertial frame spacetime functionalism is to provide a shortcut to identifying operational spacetime by identifying cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. When the metric structure is non-dynamical, and even in a large class of dynamical metric models, theoretical spacetime is indeed the same as operational spacetime, assuming stable matter configurations can be built. In the next section, however, we discuss five cases in which, even assuming that stable matter configurations exist, theoretical spacetime does not appear to coincide with operational spacetime.

4 Theoretical/operational mismatches

In this section, we present five apparent problem cases for Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism, in which theoretical spacetime comes apart from operational spacetime. We will see that, while instructive, the first example is not genuinely problematic for Knox. By contrast, we take it that the subsequent four examples are genuine problem cases.

4.1 TeVeS

Our first example concerns Bekenstein’s bimetric TeVeS (‘Tensor-Vector-Scalar’) theory—a relativistic generalisation of the ‘modified Newtonian dynamics’ (MOND) programme in cosmology (Milgrom 1983)—as presented in Bekenstein (2004, 2005), [6]. As discussed in Brown (2005, §9.5.2), in this theory the metric field which is surveyed by rods and clocks, the conformal structure of which is traced by light rays, and the geodesics of which correspond to the motion of free bodies, is not the ‘fundamental’ metric field \(g_{ab}\), but rather a less ‘fundamental’ metric field \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\), constructed from the other matter fields in the theory (Brown 2005, p. 174). In this case, both \(g_{ab}\) and \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) are Lorentzian metric fields; moreover, the matter fields in this theory obey (in the relevant regime) locally Poincaré invariant dynamical laws. Thus, one might think that, on Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism, both \(g_{ab}\) and \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) have local (Poincaré) symmetries coinciding with the local symmetries of the dynamical laws governing matter fields, so that both fields would qualify as spatiotemporal—an apparent problem.

To claim as much would be too fast—a defence of inertial frame spacetime functionalism can be mustered by drawing on the distinction between symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime, and cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. In TeVeS, it is the metric field \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\), and not the metric field \(g_{ab}\), which takes a diagonal form in the frames in which the dynamical equations governing matter fields take their simplest form (cf. Read et al. 2018, §6). Thus, while \(g_{ab}\) qualifies as symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime, it does not qualify as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. If one takes “picking out a structure of local inertial frames” to require cone coincidence, then there is room for a Knoxian spacetime functionalist to make the claim that, in TeVeS, the metric field \(g_{ab}\) is not spatiotemporal—rather, only \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) is spatiotemporal. For Knox, this is the correct verdict, since it is \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) which is to be regarded as operationally significant, in TeVeS. Thus, this example should not be taken to be a genuine problem case for Knox.

4.2 Universally coupled massive scalar gravity

Pitts (2017) presents a family of examples in order to support the claim that (putting things in our language) a given piece of geometrical structure may qualify as theoretical spacetime, but not operational spacetime. In this section, we consider Pitts’ example of universally coupled massive scalar gravity—a variant of Nordström’s massless scalar gravity theory (Norton 1992; Renn and Sauer 2007), discussed in more detail by Pitts himself in Pitts (2010, 2011, 2016), which is one of the principal examples which Pitts introduces in order to motivate the above claim.

In universally coupled massive scalar gravity, there exist two Lorentizan metric fields: the field surveyed by matter \(g_{ab}\), and a Minkowski metric field \(\eta _{ab}\); the Lagrangian includes the following graviton mass piece:

(Here, w is a free parameter, which may be fixed to yield specific theories.) In these theories, all matter couples to the same metric, \(g_{ab}\). However, the Minkowski metric \(\eta _{ab}\) nevertheless plays an ineliminable role in defining the massive graviton Lagrangian. From our point of view, the important point to note about such theories is put clearly by Pitts as follows:

Massive scalar gravity lacks Minkowskian behavior of rods and clocks, though it has the Minkowski metric (among other things) and the Poincaré symmetry group. ... [T]he chronometrically observable conformally flat metric \(g_{\mu \nu } = \hat{\eta }_{\mu \nu } {\left( -g \right) }^{1/4}\) isn’t clearly the One True Geometry. (Pitts 2017, p. 6)

That such theories present a prima facie problem for Knox’s spacetime functionalism (as we understand it) should be clear, for in such theories it would appear that the metric field \(\eta _{ab}\) picks out the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields. One might, however, question whether this example is genuinely problematic for Knox, by (as in the TeVeS case) denying that metric field \(\eta _{ab}\) in such theories qualifies as not just symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime, but also cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. Since Knox declares that only the latter is spacetime tout court, it is only if she identifies \(\eta _{ab}\) as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime that she faces a problem here.

Such a response will not work in this case.Footnote 10 Since the metric field \(\eta _{ab}\) is conformally related to the ‘chronometrically observable’ metric field \(g_{ab}\), the two diagonalise in the same frames—the volume element is just a proportionality factor between the two metrics at each point. Thus, \(\eta _{ab}\) does qualify as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime in this case (unlike \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) in TeVeS)—in spite of not being operational spacetime. So Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism misidentifies \(\eta _{ab}\) as being spatiotemporal in universally coupled massive scalar gravity—worse, the account identifies both \(\eta _{ab}\) and \(g_{ab}\) as being spatiotemporal, despite their having observably different consequences on large-scale measurements.Footnote 11

4.3 T-duality

An ubiquitous feature of a prominent class of quantum theories of gravity—that is, theories which seek to reconcile classical general relativity with quantum mechanics—is duality. For the purposes of this paper, we can take a duality to be an isomorphism of the spaces of solutions of two theories (up to equivalence classes of gauge-related solutions), such that solutions related by that mapping are empirically equivalent (in turn, the empirical equivalence of two models can be cashed out in terms of their agreeing on all empirical substructures, in the sense of van Fraassen (1980, pp. 67ff.)). In this sense, dualities present prima facie a concrete case of underdetermination of theory by evidence, for they exemplify our having to hand two different theories—which make prima facie distinct ontological claims about the world—which are nonetheless empirically equivalent. (For more on dualities and underdetermination, see Matsubara (2013), Read (2016b), Le Bihan and Read (2018)).

Our concern in the present subsection is with T-duality—one particular duality, which appears in perturbative string theory. According to the naïve ontological picture presented by perturbative string theory, reality is constituted by one-dimensional strings in some background ‘target space’, as well as by other higher-dimensional entities called ‘branes’. Moreover, reality is not made up of four spacetime dimensions (three spatial and one temporal), but rather of ten. Various classical fields are defined on target space—ultimately, these are also understood to be composed of strings; for consistency reasons, these background fields must obey the Einstein equation, plus higher-order corrections [for philosophical discussion of this, see e.g. (Huggett and Vistarini 2015; Read 2016a, 2019a)]. In the case of T-duality, models of perturbative string theory on a target space product manifold \(M \times S^1\) with radius of the compactified dimension R are found to be dual to models of perturbative string theory on the target space product manifold \(M \times S^1\) with radius of the compactified dimension proportional to 1 / R (see e.g. Becker et al. 2007, ch. 6).

To be more specific, in the case of T-duality, one of the T-dual models reads \(\mathcal {M}=\langle M\times S^1, g_{ab}, \Phi \rangle \); the other reads \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}= \langle M \times S^1, \tilde{g}_{ab}, \tilde{\Phi }\rangle \). While \(\mathcal {M}\) (say) has target space metric field \(g_{ab}\) of ‘large’ radius (proportional to R), \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\) has target space metric field \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) of ‘small’ radius (proportional to 1 / R). In both \(\mathcal {M}\) and \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\), the Lorentzian metric field in those models satisfies the Einstein equation (plus higher-order corrections), and the matter fields satisfy their own dynamical equations.Footnote 12 What can one say about the nature of spacetime in each of these models? [For more discussion on these matters, see Read (2019a)]. In \(\mathcal {M}\), the metric field \(g_{ab}\) is Lorenzian, and satisfies the Einstein equation; moreover, the dynamical equations governing the behaviour of the \(\Phi \) fields are locally Poincaré invariant. Similarly for \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) and \(\tilde{\Phi }\) in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\). Thus, on a Knoxian analysis, \(g_{ab}\) picks out a structure of local inertial frames in \(\mathcal {M}\), and \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) picks out a structure of local inertial frames in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\). Note, indeed, that \(g_{ab}\) qualifies as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime in \(\mathcal {M}\), and \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) qualifies as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\).

So far, so good. But should \(g_{ab}\) qualify as operational spacetime in \(\mathcal {M}\), and should \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) qualify as operational spacetime in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\)? Some recent considerations due to Huggett (2017), in turn drawing upon the work of Brandenberger and Vafa (1989), might lead one to question this.Footnote 13 Brandenberger and Vafa ask us to consider the following situation: imagine ourselves to be an observer ‘embedded’ in one of these T-dual models. Then, consider firing a test photon in order to measure the radius of the compactified dimension, in both \(\mathcal {M}\) and \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\). Brandenberger and Vafa argue that, in both \(\mathcal {M}\) and \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\), it is the metric field of larger compactified dimension that will be measured—that is, in both cases, it will be \(g_{ab}\) that is measured.Footnote 14 Huggett draws from these considerations the following lesson: target space cannot (as we might naïvely expect) qualify as “phenomenal space”—the classical spacetime than an agent ‘embedded’ in the model under consideration would experience—for in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\), intervals of the target space metric field \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) are not read off by our measurement apparatuses (rather, the thought experiment of Brandenberger and Vafa indicates that it is the target space metric field \(g_{ab}\) which is surveyed in this case). To put the matter in our own terminology: while the target space metric field in T-dual models of perturbative string theory might qualify as theoretical spacetime (even cone-coincident theoretical spacetime), for its symmetries coincide with the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields (that is, the Poincaré symmetries of the dynamical equations governing the matter fields \(\Phi \) in \(\mathcal {M}\) coincide with the Poincaré symmetries of the metric field \(g_{ab}\) in \(\mathcal {M}\), so that \(g_{ab}\) qualifies as theoretical spacetime in this case, and similarly for \(\tilde{\Phi }\) and \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\)), the target space metric field does not invariably qualify as operational spacetime, for its intervals are not invariably read off by physical measurement apparatuses (as is the case for \(\tilde{g}_{ab}\) in \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\)).

Given the above-mentioned operationalist tendencies which we find in Knox,Footnote 15 one might regard this as being problematic: Knox’s spacetime functionalist account appears to identify objects in perturbative string theory which qualify as theoretical spacetime, but which do not qualify as operational spacetime. And thus, again, it seems that Knox’s account does not afford her all that she is after.

4.4 Specific general relativity solutions

Although a valuable tool in the quest to identify spatiotemporal degrees of freedom in theories of quantum gravity, Knox’s spacetime functionalism was developed initially with the goal of ascertaining the structure which plays the spacetime role in established physical theories, such as Newtonian gravitation theory and general relativity. It is, therefore, especially interesting to discover a failure of Knox’s programme within the context of general relativity itself. In this subsection, we demonstrate that a class of rotating general relativistic spacetimes presents a problem for Knox’s programme—one in which her criteria for cone-coincident theoretical spacetime are met, but in which the metric field nonetheless does not have operational significance. (So, in this case, the metric field qualifies as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime, but not operational spacetime.)Footnote 16

In order for the metric field to have operational significance, it must be possible for certain matter field agglomerations—clocks—to be able to read off intervals of proper time (as given by that metric field) along their trajectories. The degree of operational significance depends, among other things, on the degree to which these matter field agglomerations can maintain their structural integrity. A matter field agglomeration satisfies the clock hypothesis if it can be used to read off intervals of proper time along its worldline—whatever that worldline may be (see e.g. (Brown and Read 2016; Maudlin 2012) for some recent philosophical discussion of the clock hypothesis). Clearly this is an unphysical requirement; all physical clocks have a breaking point. But modulo such concerns, approximate satisfaction of the clock hypothesis suffices for approximate operational significance of the metric field under consideration, in terms of clock readings.

Light clocks—simple constructions consisting of two perfectly reflecting mirrors with a photon bouncing back-and-forth between them—are often regarded as being ideal clocks, i.e. are regarded as being candidates for satisfaction of the clock hypothesis. Therefore, a scenario in which such clocks can be constructed is usually taken to be one in which the metric field has operational significance. Fletcher (2013) offers a mathematical precisification of this intuition, purporting to demonstrate how it is, in principle, possible to construct a light clock that ticks arbitrarily accurately and regularly in an arbitrary general relativity solution. If correct, Fletcher’s argument would underwrite the success of Knox’s programme in general relativity—for the metric field, which Knox identifies as spatiotemporal, could always be regarded as having operational significance, via the readings of light clocks. However, as demonstrated explicitly in Menon et al. (2018), Fletcher’s result in not universally valid. It fails in the Gödel and Kerr solutions to general relativity, for example. As we demonstrate in the remainder of this subsection, this failure is not down to a failure of cone-coincidence.

Fletcher’s proof represents a differential-geometric generalisation of a heuristic argument for the clock hypothesis in Minkowski spacetime due to Maudlin (2012, pp. 106–114). Maudlin’s argument proceeds as follows. The path traversed by a photon (more precisely, the classical analogue of a photon; a wave-packet state of the electromagnetic field) between two mirrors is a null geodesic. This is easily demonstrated by solving Maxwell’s equations. Consider a light clock at rest. The proper time elapsed along the worldline of one mirror can be calculated by using the generalisation of Pythagoras’ theorem to pseudo-Riemannian flat space. Since the distance covered by a light ray is zero (as it propagates on null geodesics), the proper time elapsed between two successive bounces of the photon off the same mirror is just twice the spatial distance between the two mirrors.

A similar argument holds for a clock in a boosted frame. For an ideal clock, the description of the clock in the boosted frame with respect to the boosted coordinates is the same as the original description with respect to the original coordinates; this is just the relativity principle. If the clock were to be a good clock, and one were to regard the boosted clock from the original unboosted frame, the mirrors would appear to have moved closer together. So we can ensure the clock is good by joining the two mirrors using a rod built out of matter governed by Lorentz-covariant laws. The natural contraction of the rod ensures the appropriate distance between the mirrors is maintained even after a boost. This takes care of the clock hypothesis for a boosted clock. Finally, to the extent that any boost can be modelled as being approximated by inertial motions separated by instantaneous impulses, the clock hypothesis is approximately satisfied by a light clock so constructed in Minkowski spacetime. Fletcher’s result is similar in spirit; although it does away with the rigid rod, it just requires that the light clock be confined to an appropriately small region of the manifold. Relying on particular features of Lorentzian manifolds, Fletcher demonstrates that such a region always exists, and with it, demonstrates that Maudlin’s result can be generalised.

Mathematically, all is well with the proof. However, like Maudlin, Fletcher relies on the assumption that light traverses null geodesics on its path between the mirrors. But this is not true in all solutions to the Einstein equation. As Asenjo and Hojman demonstrate (Asenjo and Hojman 2017), in solutions with global rotation such as Gödel and Kerr (cf. Malament 2012, ch. 3), to the extent that one can have a persisting wave packet that represents light, this packet does not traverse null geodesics; indeed it does not even traverse a path of constant velocity, but instead its velocity manifests spacetime position dependence.Footnote 17 This means that light clocks, if constructable, do not accurately read off intervals of the general relativistic metric field. The metric field, therefore, cannot be afforded operational significance via light clocks. Since light clocks are one of the simplest kinds of clock which one could imagine, in such spacetimes, the metric field does not, it appears, qualify as operational spacetime—for if even light clocks do not read off intervals of proper time along their worldlines, there is no a priori reason to expect this to be true of more complicated clocks either.

To repeat: it is interesting to note that locally, the cone structure of the metric field \(g_{ab}\) and that of the dynamical equations governing the Maxwell fields do coincide. Thus, we have in these examples an apparent case of cone-coincident theoretical spacetime, but not operational spacetime.

4.5 Supersymmetry and superspace

Our final example of a theoretical/operational spacetime mismatch derives from a subject which goes beyond the Standard Model of particle physics—namely, supersymmetry (SUSY). SUSY is a proposed (and as-yet experimentally unverified) symmetry between bosons (quantum particles which mediate forces) and fermions (quantum particles which constitute matter which feels those forces). Supersymmetric field theories are, therefore, field theories whose empirical predictions are invariant under the exchange of bosons and their fermionic supersymmetric partners, and vice versa. Note that SUSY transformations are defined between specific bosons and fermions—no particle as-yet discovered, bosonic or fermionic, is a supersymmetric partner of any other known particle. If SUSY is a symmetry of nature, then the energy regime in which we live is one significantly below the symmetry-breaking scale. In the rest of this section, we concern ourselves only with the realm of unbroken SUSY.Footnote 18

SUSY field theories make for an interesting testing ground for various philosophical claims related to spacetime, because they can be expressed in a setting that is a generalisation of Minkowski spacetime, known as superspace.Footnote 19 The simplest superspace is constructed by augmenting Minkowski spacetime with four additional dimensions. The twist is that, unlike the familiar spatial and temporal dimensions of Minkowski spacetime, these dimensions are not coordinatised by real numbers. Instead, in order to reflect the fermionic character of some of the components of a superfield—the superspace generalisation of a field, thought of as a function from superspace to some field-value space—the four extra dimensions are coordinatised by objects known as anticommuting supernumbers. A supernumber is, technically, an element of an infinite Grassmann algebra. Intuitively, an anticommuting supernumber is an object \(\chi \) such that if \(\chi \) and \(\xi \) are two anticommuting supernumbers, then \(\chi \cdot \xi +\xi \cdot \chi =0\). In other words, the order of multiplication matters—these numbers have non-trivial commutation properties. The set of complex supernumbers consists of all such anticommuting supernumbers, together with all commuting supernumbers (objects constructed out of anticommuting supernumbers such that the order of multiplication is irrelevant) and all the complex numbers.

The set of dynamical symmetry transformations common to all superfields is, by construction, the super-Poincaré group—this is an example of a ‘super-Lie group’. Super-Lie groups are a generalisation of Lie groups; whereas the latter are groups which are also smooth manifolds, the former are groups which are also superspaces (i.e., generalisations of manifolds with anti-commuting supernumber-valued coordinates). Recall that a theoretical spacetime is a geometrical structure determined by constructing geometrical objects that are invariant under transformations from the dynamical symmetry group common to all fields in question. By construction, therefore, superspace is a theoretical spacetime.Footnote 20

The Poincaré group is a subgroup of the super-Poincaré group, a fortiori, any Poincaré transformation is a dynamical symmetry of a supersymmetric theory. We therefore have a symmetry-coincident theoretical spacetime. If, in addition, we assume the light postulate, or some equivalent statement of an invariant quantity for the tangent spaces to the (ordinary) manifold subspace of superspace, we can construct a cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. Cone-coincidence is only a claim about tangent spaces to manifolds, so applies perfectly sensibly to superspace insofar as superspace is an ordinary manifold together with some other structure.

Knox’s prescription identifies as inertial those frames in which the dynamical equations governing matter fields take their simplest form. In the case under consideration here, these are those frames in which the dynamical equations governing the superfields are expressed in coordinates in which an object referred to (perhaps predictably) as the super-Minkowski interval, determined by the super-Minkowski metric [for an explicit definition of these terms, see e.g. (Buchbinder and Kuzenko 1998)], is invariant. Thus, the super-Minkowski metric plays the role of picking out ‘inertial’ frames [these frames are sometimes referred to as ‘super-inertial frames’; see e.g. (Buchbinder and Kuzenko 1998)]—it therefore qualifies as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime.

To see if the super-Minkowski metric qualifies as an operational spacetime, however, we need to assume that one can construct the appropriate generalisation of rods and clocks. Let us call these objects super-surveyors. An example of a super-surveyor would be the analogue of a light clock, but one in which the oscillating material is governed by the supersymmetric version of Maxwell’s equations, the so-called super-Maxwell equations. But, as is discussed in more detail in Menon (2018), there are good reasons to believe that the extra SUSY dimensions will not be be surveyed by such matter field configurations.

To see why this is the case, let us begin with a familiar example: deriving the Lorentz transformations in special relativity. If one begins with the relativity principle (and the assumption that spacetime is homogeneous and space is isotropic), then the Lorentz transformations follow from the further assumption of the light postulate. This latter postulate is an empirical principle that asserts two things: (1) that the invariant quantity associated with the transformations between inertial frames is a speed, and (2) that this speed has a particular numerical value. In light of the discussion in Sect. 3.1, we can conclude that a different value for this speed would lead to a different group of transformations between inertial frames. Thus, the light postulate and the relativity principle together determine the cone structure of the tangent spaces.

The problem with attempting to generalise this move to superspace is that, in that context, there exists no empirical principle analogous to the light postulate. It is possible to define the tangent space at a point in superspace, in effect by specifying algebraically the space of tangent vectors along anticommuting dimensions—for details, see (Buchbinder and Kuzenko 1998, p. 406). In postulating that the transformations between super-inertial frames are super-Poincaré transformations, and not saying anything further, the parameter that determines the tangent space cone (i.e. the null direction) for the anticommuting dimensions is left unspecified.

If we believe that our surveying devices have to be built out of SUSY-matter (and that seems reasonable; how else could they survey the superspace geometry?) then it is possible that this matter will not read off intervals of the super-interval, even if, with respect to the Minkowski subspace of superspace, we have cone coincidence. The reason is the following: all our superfields are (by construction) super-Poincaré invariant—but they might, nonetheless, still survey distinct supermetrics because they do not agree on the cone structure of the anticommuting component of the tangent space to superspace.

Thus, super-surveyors constructed in this way will not be guaranteed to give us operational access to spacetime; they might fail to pick out operational spacetime even if they unequivocally pick out (via the symmetries of their dynamical equations) a cone-coincident theoretical spacetime.

5 Proposed revisions

We have seen that some apparent problem cases for inertial frame spacetime functionalism—in particular, that presented in Sect. 4.1—do not find their mark, for they fail to appreciate the distinction between symmetry-coincident and cone-coincident theoretical spacetime. If one takes it that it is the latter notion of theoretical spacetime in which Knox is interested when she proposes her functional characterisation of spacetime in terms of picking out a structure of local inertial frames, then Knox’s approach does deliver the intuitively correct verdict on what counts as spatiotemporal in the TeVeS case. On the other hand, other apparent problem cases for inertial frame spacetime functionalism—in particular, those presented in Sects. 4.2–4.5—do find their mark, for in these cases cone-coincident theoretical spacetime does not qualify as operational spacetime—which, for Knox, is the intuitively correct notion of spatiotemporality.

These problem cases lead one to enquire how Knox’s spacetime functionalist proposal could be modified in order to deliver the intuitively correct verdict on what counts as spatiotemporal in all cases. The natural revision to propose is the following:

Spacetime is that structure which has chronometric significance.

Making this move would mean that the correct verdict on spatiotemporality would be delivered in all the cases presented in Sect. 4. However, arguably such a move would have the disadvantage that it would deprive Knox’s characterisation of spacetime of easy applicability to new cases.Footnote 21 For example, consider the case of Gödel/Kerr spacetime presented in Sect. 4.4. When one considers Maxwell fields in such a spacetime, it is easy to note that the metric field of general relativity qualifies as cone-coincident theoretical spacetime—and so spacetime for Knox tout court. However, it is very difficult—and involves substantial, non-trivial calculations—to ascertain whether this structure does or does not qualify as operational spacetime. Thus, to define spacetime in terms of operational spacetime would, arguably, diminish the ready applicability of Knox’s programme.Footnote 22 Indeed, Knox says as much herself, when she writes:

We would ideally like a formulation that entails appropriate phenomenological behaviour without requiring us to model the behaviour of complex systems. (Knox 2011, p. 5)

In light of this, one might instead wonder whether there is any way in which Knox’s original proposal could be defended. Ideally, what Knox would need to argue here is that (cone-coincident) theoretical spacetime is in general a good—albeit defeasible, in light of the cases presented in Sect. 4—guide to operational spacetime. If such a link can be rendered explicit, then there is room for Knox to retain her original functional definition of spacetime, in terms of picking out a structure of local inertial frames. What the examples presented in Sect. 4 of this paper demonstrate, however, is that such a link is not inevitable—and therefore, that there is a burden on Knox to spell out in more detail the connection between theoretical and operational spacetime, if her account (on our preferred operationalist reading) is to be compelling.

6 Baker’s proposal

When it comes to spacetime functionalism, Knox’s approach is not the only game in town. One distinct but noteworthy spacetime functionalist approach is due to Baker (2018a)—not sharing Knox’s above-mentioned operationalist leanings, Baker advances a very different functional conception of spacetime. He begins (Baker 2018a, pp. 11–12) by noting that many different factors seem to contribute to the spacetime concept:

I won’t make any attempt to give an exhaustive list of candidates here, but the following are examples of criteria which are logically independent of Knox’s inertial criteria and which seem to also count toward a structure’s satisfying our spacetime concept:

The structure is non-dynamical, at least with respect to non-gravitational interactions.

The structure is (in some sense) located everywhere in all states of the theory.

The structure does not carry energy or momentum.

“Vacuum” solutions exist which describe the (putatively) spatiotemporal structure in the absence of other structures.

There are no other structures in the theory which can exist without the (putative) spacetime structure.

The structure grounds or explains a family of modal facts about which states are geometrically possible, where geometric possibility does not reduce to physical possibility (Belot 2013, pp. 50–51).

It is a (higher-order) law of nature that the geometric symmetries of the structure are dynamical symmetries of the theory (Janssen 2009; Skow 2006).

Forces propagate across the spatial distances defined by the metric characterizing the structure (so that long-range forces like electromagnetism fall off proportionately to the inverse square of this distance, and so on).

The structure is fundamental.

Again, this is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Rather it is meant to illustrate that a vast number of different criteria could plausibly figure into our ascription of the name ‘spacetime’ to a given theoretical structure, depending on the details of the laws that define that structure. And indeed, Knox’s own criterion,

The structure determines the difference between inertial and non-inertial frames of reference,

belongs high on this list, perhaps even at the top. She has certainly shown that it’s a very important criterion. My only disagreement is with her claim that it is the sole criterion.

On the basis of these apparently myriad factors which contribute to the spacetime concept, Baker draws the natural conclusion that, ultimately, there is no unequivocal notion of spatiotemporality; rather, spacetime is a cluster concept: (Baker 2018a, p. 2)

[O]ur spacetime concept has the structure of a cluster concept. Rather than possessing a single set of necessary and sufficient conditions, cluster concepts can be satisfied in a variety of different ways by different entities falling under them.

What to make of this proposal, especially as compared with Knox’s own? On the one hand, Baker is likely correct that our pre-theoretic concept of spacetime (insofar as we have such a pre-theoretic concept!) cannot be analysed via one unequivocal set of necessary and sufficient conditions. (This, of course, is part of a broader lesson against conceptual analysis familiar from the latter half of the 20th century in all branches of analytic philosophy.) On the other hand, in light of its heterogeneity, Baker’s analysis lacks practical applicability. For example, consider the cases presented in Sect. 4—on Baker’s cluster concept approach to spacetime, which structure in each of these theories is to be regarded as spatiotemporal? In light of the complexity of the analysis, it is difficult to give any definitive answer to this question. Thus, while Baker is morally right on the nature of spacetime, his analysis has limited practical value.

Such is not the case for Knox’s proposal: Knox gives a simple, functional characterisation of spatiotemporality, which is readily applied to new spacetime theories (consider, for example, the novel work to which Knox puts her programme in, Knox (2011, 2014)). It might be the case that Knox’s criterion does not fully capture our notion of spatiotemporality (including Knox’s own—this is, of course, the central point of Sects. 4–5 above); nevertheless, the claim is that this account of spacetime can deliver intuitively correct verdicts on spatiotemporality, and so should feature as a (defeasible!) guide to spatiotemporality in new cases also. While, as argued above, Knox should be more explicit that inertial frame structure need not always constitute the sine qua non of spatiotemporality (whether (i) because one has Knox’s operationalist leanings—in which case there is a gap between theoretical and operational spacetime, or (ii) because one embraces Baker’s notion of spacetime as a cluster concept), her approach has the capacity to be put to novel interpretative work, in a manner in which Baker’s approach does not.

Thus, the final verdict on Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism versus Baker’s cluster concept spacetime functionalism is the following: while Baker’s analysis is likely closer to our overall conception of spatiotemporality, Knox’s analysis has the virtue of readily applicability to new cases. Insofar as one takes inertial frame structure to be a guide to the other qualities which feature in the spacetime concept (perhaps those on Baker’s list), one may continue to be justified in following Knox’s approach. Of course, however, one should ideally make explicit the link between inertial frame structure, and those other factors featuring in the spacetime concept.

7 Dynamical and geometrical approaches

It is sometimes claimed (see e.g. Lam and Wüthrich 2018; Myrvold 2017) that Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism “extends” previous work on the so-called dynamical approach to spacetime theories, first developed in Brown (2005), Brown and Pooley (2001, 2006). Roughly speaking, this ‘dynamical approach’ involves two claims:Footnote 23

-

1.

Fixed fields [i.e., fields fixed identically in all kinematical possibilities of a given theory—cf. (Pooley et al. 2017, p. 115)], such as the Minkowski metric field \(\eta _{ab}\) of special relativity, are to be ontologically reduced to the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields [the dynamical view is, therefore, a modern form of relationalism—cf. (Pooley 2013, Section 6.3.2)].

-

2.

Ontologically autonomous metric fields, such as \(g_{ab}\) in general relativity, do not have their chronogeometic significance—i.e., are not surveyed by physical measurement apparatuses—of necessity (i.e., in all solutions of any theory in which they appear).Footnote 24

Focussing on (2), advocates of one version of the opposing geometrical approach to spacetime theories would state that ontologically autonomous metric fields, such as \(g_{ab}\) in general relativity, do have their chronogeometic significance necessarily. However, in Read (2019b), Read et al. (2018), it was argued that this particular version of the geometrical approach is not viable—precisely because there exist problem cases for such a view, in which one has a metric field \(g_{ab}\) in one’s theory, but that structure is not surveyed by physical rods and clocks (some of the examples presented in Sect. 4 of this paper would count as problem cases of this kind for the geometrical view).Footnote 25

In any case, regardless of the particular view which one espouses in the dynamical/geometrical debate, one can ask: is it true that Knox’s spacetime functionalism is an “extension” of the dynamical view? In our view, this claim is not correct; rather, we see one’s having a particular set of commitments in this debate as being orthogonal to whether one endorses Knox’s spacetime functionalism. Our reasons are the following: whether one thinks that a given metric field is ontologically reducible to dynamical symmetries, or does or does not have its chronogeometric significance necessarily, is distinct from the question of whether one should regard this object as being spatiotemporal, on Knox’s functional analysis of spacetime. Suppose, for example, that one endorses the dynamical approach to spacetime theories—then on Knox’s programme one will, in light of (2) above, deny that e.g. a Lorentzian metric field \(g_{ab}\) always qualifies as spatiotemporal—for whether this is so will depend upon particular facts about the matter sector of the theory under consideration. On the other hand, if one denies (2) (à la the strong version of the geometrical approach above), then one will think that a generic Lorentizan metric field \(g_{ab}\) always qualifies as spatiotemporal. Not only are both of these dynamical and geometrical views perfectly compatible with Knox’s spacetime functionalism, but, moreover, they would also be compatible with a different functional conception of spacetime—or, indeed, with certain non-functional approaches to spacetime.

Though the above is, essentially, our final take on this matter, two further remarks are in order in this vicinity. First, one way to understand the geometrical approach in contrast with the dynamical approach is that the former is willing to make certain ‘riskier’ assumptions about the chronogeometric status of a given field (e.g. \(g_{ab}\)) than the dynamical approach is willing to countenance. We have seen in Sect. 5 above, however, that an underlying assumption of Knox’s approach is that theoretical spacetime is a good guide to operational spacetime. In this sense, Knox too is (arguably) making an a priori assumption about the nature of certain fields which appear in our physical theories. In this very particular sense, one might argue that such assumptions place Knox closer to the geometrical rather than the dynamical view. This should be surprising, since, as noted above, several authors tie Knox’s spacetime functionalism more closely to the dynamical approach, than to the geometrical approach.

A final word on the dynamical approach, in light of the distinctions which have been drawn in this paper. As mentioned above, in the context of theories with fixed metric structure, such as special relativity, advocates of the dynamical approach state that such structure just is a codification of the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields in the theory; in this way, they seek to reduce metric structure to dynamical symmetries [for more on this, see Brown and Read (2019), Myrvold (2017)]. For example, if the dynamical equations governing matter fields are invariant under Poincaré transformations, then one just has a Minkowski metric in one’s theory. In Stevens (2015), it is argued that the dynamical approach should, therefore, be understood as a means of identifying spacetime structure with what Einstein dubbed in 1921 practical geometry (Einstein 1921)—that is, that geometrical structure which is actually surveyed by physical measurement apparatuses. In light of our distinction between theoretical and operational spacetime, however, we can see that this claim is in general too fast—while it might be true for theories such as special relativity, it is not in general correct to state that what we have called in this paper ‘operational spacetime’—Einstein’s ‘practical geometry’—is the same as that structure which codifies the symmetries of the dynamical equations governing matter fields. A certain degree of caution is, therefore, apposite when approaching such claims.

8 Conclusions

The central aim of this paper has been to identify and diagnose problems for inertial frame spacetime functionalism. The diagnosis made it clear that more needs to be done than Knox might have initially anticipated in identifying the chronogeometric structure of dynamical fields—Knox’s shortcut from universal symmetries to generic field behaviour is not universally valid.

While Baker’s approach might preferable to that of Knox vis-à-vis identification of all aspects of the spacetime concept, from the point of view of practical utility and applicability, Knox’s approach is to be preferred. If one shares Knox’s operationalist point of view, then one faces an urgent burden to bridge the gap between theoretical and operational spacetime. In our view, this is not indicative of the failure of Knox’s approach—but rather simply that there remains much more work to be done in fully elaborating this position.

Notes

We ought to mention that the Knoxian functionalist project is distinct from the Lewisian project of theoretical reduction, the latter also sometimes discussed under the banner of ‘functionalism’ (see Lewis 1970). The Lewisian project regards the reduction of so-called t-terms (‘troublesome’ terms that are not well understood in some domain of discourse) to o-terms (‘old’ or antecedently sufficiently well-understood terms from a different domain of discourse). In the context of spacetime theories, Gomes and Butterfield (2019) are interested in the reduction of the troublesome notion of ‘time’ in, for example, general relativity to non-temporal, dynamical structures defined on the theory’s phase space. Call this a form of formal reductionism. The Knoxian project, on the other hand, is not a form of formal reductionism. It is more akin to the Bridgmannian project of defining, operationally, a certain theoretically salient structure, using the same procedure across distinct theories. Investigation of the extent to which these two projects’ aims diverge presents an interesting avenue for future research.

This way of putting things strengthens the connection (in our view still under-explored) with functionalism in the philosophy of mind—cf. (Levin 2018).

Knox’s version of the SEP draws on that presented by Brown at (Brown 2005, p. 169).

There are significant complications here regarding whether the SEP should be understood to hold at a point in the manifold of general relativity, or to hold in the neighbourhood of a point. Moreover, there are subtleties regarding approximations which must be assumed in order to deliver such local coincidence of symmetries. For detailed discussion of these issues, see Read et al. (2018); we set them aside in this paper. It should also be mentioned that we are in full agreement with Lehmkuhl when he describes the SEP as a “bridge principle” between general relativity and special relativity—see (Lehmkuhl 2019, Section 4).

It is worth drawing attention en passant to another tension in Knox’s approach. In canonical applications of her inertial frame spacetime functionalism (such as to Newtonian gravity—see Knox (2014)), Knox applies the programme to theories in which the notion of operational content is problematic from the outset. In particular, because Newtonian gravity lacks stable bulk matter, the notion of a physical rod or clock in that theory is not just idealised, but requires denying the truth (or at least the completeness) of the theory’s laws in order to be taken seriously. Many thanks to an anonymous referee for this astute observation.

Or, more generally should we wish to accommodate Newtonian theories, a given piece of geometrical structure—not necessarily a metric field.

For dialectical reasons, our focus in this paper is on the lightcone structure in the tangent spaces of the manifold. This does not mean that we are claiming that conformal structure on its own determines spacetime structure. Implicit in our discussion is the moral from Weyl (1921, 1923) and Ehlers et al. (1972), that conformal and projective structure together determine (up to an overall volume factor) the metric structure of spacetime. When we speak of cone-coincidence, we therefore also assume coincidence of projective structure.

This constant is, of course, the one-way speed of light. Nothing that we say in this paper turns on the choice of synchrony convention used to arrive at this constant. However, for dialectical clarity, we assume spatial isotropy, and the Einstein-Poincaré synchrony convention.

In other words, the outer (blue) cone is one for which our coordinates are normalised, and \(c=1\); which makes the invariant speed corresponding to the inner (red) cone, \(c'<1\). The first set of matter fields will be Lorentz invariant under Lorentz transformations where the parameter is c (i.e. the \(\gamma \) parameter is of the form \(\gamma =\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}\)); the second set will be invariant under Lorentz transformations where the parameter is \(c'\) (i.e. the \(\gamma \) parameter is of the form \(\gamma =\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c'^2}}}\)).

Thanks to Brian Pitts for discussion on this point.

Of course, Knox could just accept multiple realisability here—our thanks to Jeremy Butterfield for pointing this out.

Unlike e.g. the case of general relativity, however, in perturbative string theory there is no freedom to choose the dynamical equations governing matter fields independently of the Einstein equation—see Read (2019a).

The remainder of this subsection proceeds on the assumption that the Huggett–Brandenberger–Vafa analysis is correct.

Presumably, the thought here is that one fires a photon around the compactified dimension, then uses a clock to record the interval of time taken for the photon to return; in the world associated with both \(\mathcal {M}\) and \(\tilde{\mathcal {M}}\), this will be the interval of time associated with the target space manifold of ‘large’ radius.

To be clear: we take Knox to be an operationalist only with respect to the spacetime concept: for Knox (as we read her), spacetime is essentially related to measurability via physical measurement apparatuses, such as rods and clocks. We do not attribute to Knox the stronger thesis of Bridgmanian operationalism, according to which “we mean by any concept nothing more than a set of operations; the concept is synonymous with the corresponding set of operations” (Bridgman 1927, p. 5). (For an illuminating recent survey of this form of operationalism, see Chang (2009).) We do, however, agree that it would be useful for Knox to clarify why her operationalism is more defensible in the spacetime context than in general—our thanks to an anonymous referee for raising this concern.

We wish to register here a prima facie tension between the Asenjo-Hojman result, and a recent, distinct result of Geroch and Weatherall (2018), according to which ‘small bodies’ built from Maxwell fields ‘track’ null geodesics of the Levi-Civita connection. If it turns out that the Geroch–Weatherall result is correct, and the Asenjo-Hojman result incorrect, then this would render the examples presented in this subsection impotent. Our belief here, however, is that the tension between these results is only apparent—for the Geroch–Weatherall result assumes global hyperbolicity, which is violated in the spacetimes which Asenjo and Hojman consider. To fully address the interplay between these two works is likely to constitute a fascinating avenue for future pursuit.

Note that this use of ‘superspace’, to refer to the spacetime setting of a SUSY field theory, is distinct from the homonymous term used in the context of canonical geometrodynamics (see e.g. (Giulini 2009) for a review) to refer to a space of spatial 3-metrics.

Baker argues in Baker (2018b) that Knox’s inertial frame spacetime functionalism cannot actually establish the result that superspace is (in our terminology) theoretical spacetime, for Knox’s account depends on a prior specification of frames of reference as either frames on Minkowski spacetime or frames on superspace. In this paper, we set this issue aside.

Though one can, of course, ask: “Why should it be easy to find the realiser of the functional role in question?” Our thanks to Jeremy Butterfield and an anonymous reviewer for this comment—with which we have some sympathies.

It is also interesting to note that making this move would compel one to identify spacetime at the level of solutions, rather than theories.

This latter point is what Butterfield calls in Butterfield (2007) ‘Brown’s moral.’

While in this paper we do assume that this particular version of the geometrical approach is untenable, we are otherwise agnostic on the dynamical/geometrical debate. Indeed, in Read (2019b), it was argued that there exist other, perfectly viable versions of the geometrical approach—roughly speaking, these versions of the geometrical approach accept (2), but continue to reject (1).

References

Asenjo, F. A., & Hojman, S. A. (2017). Do electromagnetic waves always propagate along null geodesics? Classical and Quantum Gravity, 34, 205011.

Baker, D. J. (2018). Interpreting supersymmetry, http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/15119/. Accessed Dec 2018.

Baker, D. J. (2018). On spacetime functionalism, http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/14301/. Accessed Dec 2018.

Becker, K., Becker, M., & Schwarz, J. (2007). String theory and M-theory: A modern introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bekenstein, J. D. (2004). An alternative to the dark matter Paradigm: Relativistic MOND gravitation, invited talk at the 28th Johns Hopkins workshop on current problems in particle theory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Bekenstein, J. D. (2005). Relativistic gravitation theory for the MOND paradigm. Available at arXiv:astro-ph/0403694.

Belot, G. (2013). Geometric possibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brandenberger, R., & Vafa, C. (1989). Superstrings in the early universe. Nuclear Physics B, 316, 391–410.

Bridgman, P. W. (1927). The logic of modern physics. New York: Macmillan.

Brown, H. R. (2005). Physical relativity: spacetime structure from a dynamical perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, H. R., & Pooley, O. (2001). The origins of the spacetime Metric: Bell’s Lorentzian Pedagogy and its significance in general relativity. In C. Callender & N. Huggett (Eds.), Physics meets philosophy at the Plank scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, H. R., & Pooley, O. (2006). Minkowski space-time: A glorious non-entity. In D. Dieks (Ed.), The ontology of spacetime. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Brown, H. R., & Read, J. (2016). Clarifying possible misconceptions in the foundations of general relativity. American Journal of Physics, 84(5), 327–334.

Brown, H. R., & Read, J. (2019). The dynamical approach to spacetime theories. In E. Knox & A. Wilson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philosophy of physics. London: Routledge.

Buchbinder, I. L., & Kuzenko, S. M. (1998). Ideas and methods of supersymmetry and supergravity: Or a walk through superspace. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Butterfield, J. (2007). Reconsidering relativistic causality. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 21(3), 295–328.

Chang, H. (2009). Operationalism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/operationalism/.

Ehlers, J., Pirani, F. A. E., & Schild, A. (1972). The geometry of free fall and light propagation. In L. O’Reifeartaigh (Ed.), General relativity: Papers in honour of J. L. Synge (pp. 63–84). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Einstein, A. (2015). Non-Euclidean geometry and physics, document 220 of D. K. Buchwald, J. Illy, Z. Rosenkranz, T. Sauer and O. Moses (Eds.), The Einstein papers project Vol. 14: The Berlin Years: Writings & Correspondence, April 1923-May 1925, pp. 215–218. Translated from Albert Einstein, Nichteuklidische Geometrie und Physik, Die Neue Rundschau 36(1), pp. 16–20, 1925.

Einstein, A. (1921). Geometrie und Erfahrung: Erweiterte Fassung des Festvortrages Gehalten an der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, am 27 Januar 1921. Berlin: Springer.

Fletcher, S. C. (2013). Light clocks and the clock hypothesis. Foundations of Physics, 43, 1369–1383.

Geroch, R., & Weatherall, J. O. (2018). The motion of small bodies in space-time. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 364(2), 607–634.

Giulini, D. (2009). The superspace of geometrodynamics. General Relativity and Gravitation, 41, 785–815.

Gomes, H., & Butterfield, J. (2019). Functionalism about time II.

Huggett, N. (2017). Target space \(\ne \) space, studies in the history and philosophy of modern. Physics, 59, 81–88.

Huggett, N., & Vistarini, T. (2015). Deriving general relativity from string theory. Philosophy of Science, 82(5), 1163–1174.

Janssen, M. (2009). Drawing the line between kinematics and dynamics in special relativity. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 40, 26–52.

Knox, E. (2011). Newton-cartan theory and teleparallel gravity: The force of a formulation. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 42, 264–275.

Knox, E. (2013). Effective spacetime geometry. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 44, 346–356.

Knox, E. (2014). Newtonian spacetime structure in light of the equivalence principle. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 65(4), 863–880.

Knox, E. (2017). Physical relativity from a functionalist perspective. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics,. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsb.2017.09.008.

Lam, V., & Wüthrich, C. (2018). Spacetime is as spacetime does. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 64, 39–51.

Le Bihan, B., & Read, J. (2018). Duality and ontology. Philosophy Compass, 13(12), e12555.

Lehmkuhl, D. (2019). The Equivalence principle(s). In E. Knox & A. Wilson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philosophy of physics. London: Routledge. (Forthcoming.).

Levin, J. (2018). Functionalism, In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

Lewis, D. (1970). How to define theoretical terms. Journal of Philosophy, 67(13), 427–446.

Malament, D. B. (2012). Topics in the foundations of general relativity and Newtonian gravitation theory, Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Matsubara, K. (2013). Realism, underdetermination and string theory dualities. Synthese, 190, 471–489.

Maudlin, T. (2012). Philosophy of physics: space and time, Princeton. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Menon, T,, Linnemann, N., & Read, J. (2018). Clocks and chronogeometry: Rotating Spacetimes and the relativistic Null hypothesis, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. (Forthcoming.)

Menon, T. (2018). Taking up superspace-The spacetime structure of supersymmetric field theory. In N. Huggett, B. Le Bihan, & C. Wüthrich (Eds.), Philosophy Beyond spacetime: The philosophical foundations of spacetime. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Forthcoming.).

Milgrom, M. (1983). A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal, 270, 365–370.

Myrvold, W. (2017). How could relativity be anything other than physical?, Studies in history and philosophy of modern physics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsb.2017.05.007.

Norton, J. D. (1992). Norton, Einstein, Nordström and the early demise of scalar, Lorentz-Covariant theories of gravitation. Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 45(1), 17–94.

Pitts, J. B. (2017). Space-time constructivism vs. modal provincialism: Or, how special relativistic theories needn’t show Minkowski chronogeometry, studies in history and philosophy of modern physics. (Forthcoming.)

Pitts, J. B. (2010). Permanent underdetermination from approximate empirical equivalence in field theory: Massless and massive scalar gravity, neutrino, electromagnetic, Yang-Mills and gravitational theories. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 62(2), 259–299.

Pitts, J. B. (2011). Massive Nordström scalar (Density) gravities from universal coupling. General Relativity and Gravitation, 43(3), 871–895.

Pitts, J. B. (2016). Space-time philosophy reconstructed via massive Nordström scalar gravities? vs. geometry, conventionality, and underdetermination. Laws, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 53, 73–92.

Pooley, O. (2013). Substantivalist and relationist approaches to spacetime. In R. Batterman (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of philosophy of physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pooley, O. (2017). Independence, background, & invariance, diffeomorphism and the meaning of coordinates. In D. Lehmkuhl, G. Schiemann, & E. Scholz (Eds.), Towards a theory of spacetime theories. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Read, J. (2016a). Background independence in classical and quantum gravity, B.Phil. thesis.

Read, J. (2016b). The interpretation of string-theoretic dualities. Foundations of Physics, 46(2), 209–235.

Read, J. (2019a). On miracles and spacetime. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 65, 103–111.

Read, J. (2019b). Explanation, geometry, and conspiracy in relativity theory. In C. Beisbart, T. Sauer, & C. Wüthrich (Eds.), Thinking about space and time: 100 years of applying and interpreting general relativity, Einstein studies series (Vol. 15). Basel: Birkhäuser. (Forthcoming).

Read, J., Brown, H. R., & Lehmkuhl, D. (2018). Two miracles of general relativity. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 64, 14–25.

Renn, J., & Sauer, T. (2007). Pathways out of classical physics. In J. Renn (Ed.), The genesis of general relativity (pp. 113–312). Berlin: Springer.

Skow, B. (2006). Review of Harvey. In R. Brown (Ed.), Physical relativity: Space-time structure from a dynamical perspective, Notre Dame philosophical reviews. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

Stevens, S. (2015). The dynamical approach as practical geometry. Philosophy of Science, 82, 1152–1162.

van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weyl, H. (1921). Zur Infinitesimalgeometrie: Einordnung der Projektiven und der Konformen Auffasung, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse, Göttingen, pp. 99–112.

Weyl, H. (1923). Mathematische Analyse des Raumproblems, lecture 3, Berlin.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dave Baker, Jeremy Butterfield, Erik Curiel, Eleanor Knox, Brian Pitts, Syman Stevens, Jim Weatherall, to the participants at a 2018 workshop on spacetime functionalism in Geneva, to the Cambridge Simplex, and to the anonymous referees, for valuable feedback and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Read, J., Menon, T. The limitations of inertial frame spacetime functionalism. Synthese 199 (Suppl 2), 229–251 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02299-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02299-2