Abstract

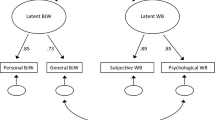

Research conducted in France and Portugal has consistently found that expressing high versus low Belief in a Personal Just World (BJW-P) is more socially valued. Results concerning the Belief in a General Just World (BJW-G) have been mixed. We propose this reflects a higher resistance of BJW-P social value to contextual changes. Testing this idea was the main goal of three experimental studies conducted in France, Germany and Portugal. In Study 1 (N = 283) participants expressed higher BJW-G when asked to convey a positive versus a negative image in a job application at a bank. The opposite pattern showed up when they applied for a job at a Human Rights NGO, an employment assistance institution and a trade union. Participants expressed higher BJW-P in all contexts, except at the trade union (no significant differences). In Study 2 (N = 489) participants judged bogus candidates who expressed high or low BJW-P/G while applying for a job at the same contexts. The patterns of judgments replicated those of self-presentations in Study 1. In Study 3 (N = 158), participants were asked to judge targets who expressed high versus moderate versus low BJW-P at a trade union. The former target was more socially valued than the other two. High versus low BJW-P expression was associated with higher stamina and less unadjusted self-enhancement. We conclude that in Western societies the expression of BJW-P is more central to the legitimation of the status quo and that of BJW-G is more context sensitive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, as reviewed, Testé and Perrin’s (2013) results involving the expression of BJW-P and Gangloff and Duchon’s (2010) results involving the expression of BJW-G in France are consistent with Alves and Correia’s (2008, 2010a) in Portugal. The divergent patterns involving the expression of BJW-G exist not only between countries, but also within France. Possibly, while responding, participants evoked different contexts for reasons we cannot ascertain now. If, as Alves and Correia (2010b) suggested and we intend to show here, the expression of BJW-G is indeed context sensitive, the various contexts that participants evoked may have influenced their responses differently. Although it is not possible to ascertain whether nor why participants in different studies evoked different contexts, that possibility seems more plausible than an explanation based on hypothetical “cultural differences” between France and Portugal (which would also have to predict deep cultural differences within France).

There were significant main effects of BJW spheres, F(1, 275) = 54.78, p < .001, η 2 p = .17, and images within contexts, F(3, 825) = 94.18, p < .001, η 2 p = .26. Specifically, participants used higher BJW-P to self-present positively and higher BJW-G to self-present negatively (M = 1.16, SD = 1.68 vs. M = − 0.25, SD = 1.49). As regards images within contexts, when participants conveyed a positive rather than a negative image at an institution or, especially, at a bank, they used higher BJW (M = 0.54, SD = 2.66 and M = 2.16, SD = 1.99; p < .001, respectively). When participants applied for a job at a union or at a Human Rights NGO, their scores were equally higher when they were conveying a negative rather than a positive image (M = − 0.56, SD = 2.63 vs. M = − 0.29, SD = 2.73; p = .40).

With items 1 and 2 we had originally intended to measure target social desirability, that is those characteristics that make individuals attractive in the eyes of others (e.g., nice, warm, pleasant), thus having interpersonal value. With items 3 and 4 we intended to measure target social utility, that is the characteristics that Western, economically liberal societies evaluate as essential if their members are to become successful (e.g., autonomous, industrious, entrepreneurial), thus having market value (Beauvois & Dépret, 2008; Cambon, 2006). With item 5 we intended to have a more behavioral measure. Exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation, however, identified four general “social value” factors explaining 80.96% of variance, each of which comprised the five items by context: λinstitution = 4.30 (loadings: .83–.87); λbank = 3.98 (loadings: .89–.90); λunion = 3.97 (loadings: .77–.88); λNGO = 3.95 (loadings: .73–.87). The factorial solution did not differ among the countries.

There was also a main effect of contexts, indicating that the targets who applied for a job at a union versus an institution were judged as having higher social value (M = 3.95, SD = 1.43 vs. M = 3.71, SD = 1.44; p = .004), F(3, 1446) = 3.97, p = .01, η 2 p = .01. Finally, there was a context by degree of BJW expressed, F(3, 1446) = 65.20, p < .001, η 2 p = .12. When the targets applied for a job at a bank, those who expressed high vs. low BJW were judged as having higher social value (M = 4.55, SD = 1.21 vs. M = 3.16, SD = 1.16; p <.001). When they applied for a job at a union the pattern was reversed (M = 3.75, SD = 1.47 vs. M = 4.14, SD = 1.37; p = .03). There were no significant differences regarding the Human Rights NGO (p = .20) or the institution (p = .48).

We first conducted a factorial analysis with Varimax rotation including all items (except the distractors). This resulted in a six-factor solution with eigenvalues higher than 1 explaining 69.70% of variance. We excluded: (a) “If someone responds to the questionnaire like this in a trade union, they will convey a bad image of themselves.”; “Responses similar to those of this person diminish the bargaining power of trade unionists.” which comprised (an uninterpretable) Factor 6 (with the latter item also having a high loading in Factor 3); and (b) “In order to improve the labour situation, it is necessary to say something similar to what the person answered in the questionnaire,” which had a high loading in Factor 5 only.

We then ran another factorial analysis with Varimax rotation, which indicated a four-factor solution explaining 66.30% of variance. We aggregated Factors 1 and 3 (the latter comprising the five items used in Study 2) to calculate our measure of target social value. This aggregation is justified statistically by the fact that Factors 1 and 3 were highly correlated (r = .76) with three items having high loadings on both factors (≥ .49). Importantly, in terms of meaning, the items of both factors refer to the social value of the targets and of what they expressed. Finally, exploratory analyses comparing our social value measure versus a measure without Factor 3 items versus a measure comprising only Factor 3 items indicated similar results.

One could also argue that the ambivalence found in Testé and Perrin (2013) could be the result of their using Lipkus et al. (1996) BJW-G scale. We think this is a very unlikely possibility. Indeed, Alves and Correia (2008, 2010a, 2013) used Dalbert et al.’s (1987) scale, which comprises very similarly worded items, and found no such ambivalence. Also, research that used the very differently worded scale by Rubin and Peplau (1975) arrived at conclusions that are in line with BJW-G expression being socially valued, not ambivalent (e.g., Duchon & Gangloff, 2008; Gangloff, 2008).

References

Abarri, L., Gangloff, B., & Fares, R. (2016). L’orientation à la dominance sociale comme facteur amplificateur de la croyance en un monde juste et de l’allégeance en milieu organisationnel [Social domination orientation as an amplifier of the belief in a just world and allegiance in the organizationa. In V. Majer, P. Salengros, A. Di Fabio, & C. Lemoine (Eds.), Facteurs de la santé au travail : Du mal-être au bien-être (pp. 221–231). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Alves, H. V., Breyner, M. M., Nunes, S. F., Pereira, B. D., Silva, L. F., & Soares, J. G. (2015). Are victims also judged more positively if they say their lives are just? Psicologia, 29, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.17575/rpsicol.v29i2.1064.

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2008). On the normative of expressing the belief in a just world: Empirical evidence. Social Justice Research, 21, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0060-x.

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2010a). Personal and general belief in a just world as judgement norms. International Journal of Psychology, 45, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590903281120.

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2010b). The strategic expression of personal belief in a just world. European Psychologist, 15, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000020.

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2013). The buffering-boosting hypothesis of the expression of general and personal belief in a just world for successes and failures. Social Psychology, 44, 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000151.

Bacharach, B., & Sager, C. B. (1982). That’s what friends are for [Recorded by Rod Stewart]. On Night shift soundtrack (record). Warner Bros.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Fitz, C. C., Alizaga, N. M., & Zucker, A. N. (2015). Tracking homo oeconomicus: Development of the neoliberal beliefs inventory. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3, 71–88. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v3i1.366.

Beauvois, J.-L., & Dépret, E. (2008). What about social value? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23, 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172755.

Bègue, L., & Bastounis, M. (2003). Two spheres of belief in justice: Extensive support for the bidimensional model of belief in a just world. Journal of Personality, 71, 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.7103007.

Bennett, R., & Kottasz, R. (2012). Public attitudes towards the UK banking industry following the global financial crisis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 30, 128–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321211210877.

Callan, M. J., Sutton, R. M., Harvey, A. J., & Dawtry, R. J. (2014). Immanent justice reasoning: Theory, research, and current directions. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 49, pp. 105–161). London: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00002-0.

Cambon, L. (2006). Désirabilité sociale et utilité sociale, deux dimensions de la valeur communiquée par les adjectifs de personnalité [Social desirability and social utility, two dimensions of value communicated by personality adjectives]. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 19, 125–151.

Cichocka, A., & Jost, J. T. (2014). Stripped of illusions? Exploring system justification processes in capitalist and post-Communist societies. International Journal of Psychology, 49, 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12011.

Correia, I., Vala, J., & Aguiar, P. (2001). The effects of belief in a just world and victim’s innocence on secondary victimization, justice and victim’s deservingness. Social Justice Research, 14, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014324125095.

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12, 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022091609047.

Dalbert, C., Montada, L., & Schmitt, M. (1987). Glaube an die gerechte Welt als Motiv: Validierung zweier Skalen [The belief in a just world as a motive: Validation of two scales]. Psychologische Beitrage, 29, 596–615.

de Gaulejac, V. (2005). La societé malade de la gestion: Idéologie gestionnaire, pouvoir managérial et harcèlement social [The sick society of management: Managerial ideology, managerial power and social harassment]. Paris: Seuil.

Deconchy, J.-P. (2011). Croyances et idéologies. Systèmes de représentations, traitement de l’information sociale, mécanismes cognitifs [Beliefs and ideologies. Systems of representations social information processing, cognitive mechanismes]. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Psychologie Sociale (pp. 335–362). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Dittmar, H., & Dickinson, J. (1993). The perceived relationship between the belief in a just world and sociopolitical ideology. Social Justice Research, 6, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01054461.

Dubois, N. (1994). La norme d’internalité et le libéralisme [The norm of internality and liberalism]. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

Dubois, N. (2000). Self-presentation strategies and social judgments—desirability and social utility of causal explanations. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 59, 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1024//1421-0185.59.3.170.

Dubois, N. (2005). Normes sociales de jugement et valeur: Ancrage sur l’utilité et ancrage sur la désirabilité [Social judgment norms and value: Anchorage on utility and anchorage on desirability]. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 18, 43–79.

Dubois, N., & Beauvois, J.-L. (2003). Some bases for a sociocognitive approach to judgement norms. In N. Dubois (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms. London: Routledge.

Dubois, N., & Beauvois, J.-L. (2005). Normativeness and individualism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.236.

Duchon, C., & Gangloff, B. (2008). Clairvoyance normative de la croyance en un monde juste: Une étude sur des chômeurs [Belief in a just world normative clearsightedness: A study with unemployed individuals]. Proceedings of the 14ème Congrès de Psychologie du Travail de Langue Française, (Vol. 4, pp. 113–122) (Hammamet, Tunisia, 2006).

Dzuka, J., & Dalbert, C. (2002). Mental health and personality of Slovak unemployed adolescents: The impact of belief in a just world. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 732–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00240.x.

Dzuka, J., & Dalbert, C. (2007). Teachers’ well-being and the belief in a just world. European Psychologist, 12, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.4.253.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878.

Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research over the past decade. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00072-7.

Gangloff, B. (2008). Normativité de la croyance en un monde juste via le “paradigme du législateur”: une étude sur des recruteurs [Normativeness of the belief in a just world via the “legislator paradigm”]. Proceedings of the 14ème Congrès de Psychologie du Travail de Langue Française, (Vol. 4, pp. 103–112) (Hammamet, Tunisia, 2006).

Gangloff, B., Abdellaoui, S., & Personnaz, B. (2007). De quelques variables modulatrices des relations entre croyance en un monde juste, internalité et allégeance : Une étude sur des chômeurs [On some modulating variables in the relationship between the belief in a just world, internality and allegeance]. Les Cahiers de Psychologie Politique, 11. Retrieved from http://lodel.irevues.inist.fr/cahierspsychologiepolitique/index.php?id=559.

Gangloff, B., & Duchon, C. (2010). La croyance en un monde du travail juste et sa valorisation sociale perçue [The belief in a just working world and its perceived social valuation]. Humanisme et Enterprise, 248, 51–64.

Gangloff, B., & Mazilescu, C.-A. (2015). Is it desirable or useful to believe in a just world? Revista de Cercetare Si Interventie Sociala, 51, 150–161.

Gangloff, B., Soudan, C., & Auzoult, L. (2014). Normative characteristics of the just world belief: A review with four scales. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 163–174.

Gilibert, D., & Cambon, L. (2003). Paradigms of the sociocognitive approach. In N. Dubois (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms (pp. 38–69). London: Routledge.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 128–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.128.

Hafer, C. L., & Sutton, R. M. (2016). Belief in a just world. In M. Schmitt & C. Sabbagh (Eds.), The justice motive: History, theory, and research. Handbook of social justice theory and research. New York: Springer.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67, 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028.

Holtgraves, T., & Srull, T. K. (1989). The effects of positive self-descriptions on impressions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 452–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167289153014.

Iatridis, T., & Fousiani, K. (2009). Effects of status and outcome on attributions and just-world beliefs: How the social distribution of success and failure may be rationalized. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 415–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.12.002.

Jellison, J. M., & Green, J. (1981). A self-presentation approach to the fundamental attribution error: The norm of internality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 643–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.4.643.

Jose, P. E. (1990). Just-World reasoning in children’s immanent justice judgments. Child Development, 61, 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02839.x.

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2005). Antecendents and consequences of system-justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00377.x.

Kaiser, C. R., & Major, B. (2006). A social psychological perspective on perceiving and reporting discrimination. Law and Social Inquiry, 31, 801–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2006.00036.x.

Khera, M. L. K., Harvey, A. J., & Callan, M. J. (2014). Beliefs in a just world, subjective well-being and attitudes towards refugees among refugee workers. Social Justice Research, 27, 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-014-0220-8.

Kluegel, J. R., & Smith, E. (1981). Beliefs about stratification. Annual Review of Sociology, 7, 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.07.080181.000333.

Leary, M. R. (1995). Self-presentation: Impression management and interpersonal behavior. Madison, Wisconsin: Brown & Benchmark.

Lerner, M. J. (1977). The justice motive: Some hypotheses as to its origins and forms. Journal of Personality, 45, 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1977.tb00591.x.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum Press.

Lerner, M. J., & Simmons, C. H. (1966). The observer’s reaction to the “innocent victim”: Compassion or rejection? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023562.

Lima-Nunes, A., Pereira, C. R., & Correia, I. (2013). Restricting the scope of justice to justify discrimination: The role played by justice perceptions in discrimination against immigrants. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 627–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1981.

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., & Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296227002.

Meyer, E. (2014). The culture map : Breaking through the invisible boundaries of global business. New York: PublicAffairs.

Miller, D. T. (1999). The norm of self-interest. American Psychologist, 54, 1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1053.

Otto, K., & Schmidt, S. (2007). Compensatory effects of belief in a just world. European Psychologist, 12, 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.4.272.

Piaget, J. (1965). The moral judgment of the child. New York: Free Press.

Pirlott, A. G., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2016). Design approaches to experimental mediation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.09.012.

Ratner, R. K., & Miller, D. (2001). The norm of self-interest and its effects on social action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.5.

Roca, B. (2016). The role of social networks in trade union recruitment: The case study of a radical union in Spain. Global Labour Journal. https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v7i1.2354.

Rubin, Z., & Peplau, L. A. (1975). Who believes in a just world? Journal of Social Issues, 31, 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00997.x.

Soudan, C., & Gangloff, B. (2013). Croyance en un monde juste et réactions aux injustices professionnelles [Belief in a just world and reactions to professional injustice]. Carréologie, 13, 137–155.

Stevens, C. K., & Kristof, A. L. (1995). Making the right impression: A field study of applicant impression management during job interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.5.587.

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2005). Justice for all, or just for me? More evidence of the importance of the self-other distinction in just-world beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.010.

Sutton, R. M., Douglas, K. M., Wilkin, K., Elder, T. J., Cole, J. M., & Stathi, S. (2008). Justice for whom, exactly? Beliefs in justice for the self and various others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207312526.

Testé, B., Maisonneuve, C., Assilaméhou, Y., & Perrin, S. (2012). What is an “appropriate” migrant? Impact of the adoption of meritocratic worldviews by potential newcomers on their perceived ability to integrate into a Western society. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 263–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1844.

Testé, B., & Perrin, S. (2013). The impact of endorsing the belief in a just world on social judgments: The social utility and social desirability of just-world beliefs for self and for others. Social Psychology, 44, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000105.

van den Bos, K., & Maas, M. (2009). On the psychology of the belief in a just world: Exploring experiential and rationalistic paths to victim blaming. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1567–1578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209344628.

Vermunt, R., & Steensma, H. (2008). Stress and justice in organizations: An exploration into justice processes with the aim to find mechanisms to reduce stress in justice. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace, from theory to practice (pp. 27–48). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wu, M. S., Yan, X., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Li, J., Zhu, Z., et al. (2011). General belief in a just world and resilience: Evidence from a collectivistic culture. European Journal of Personality, 25, 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.807.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alves, H.V., Gangloff, B. & Umlauft, S. The Social Value of Expressing Personal and General Belief in a Just World in Different Contexts. Soc Just Res 31, 152–181 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0306-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0306-9