Abstract

The harmfulness of negative stereotypes toward gay and lesbian people has been established, but the effect of positive stereotypes has not been thoroughly examined. Gay and lesbian Americans continue to struggle against interpersonal and institutionalized discrimination, yet many people do not see them as a politically disadvantaged group, and voter support for gay rights has been inconsistent and somewhat unpredictable. Drawing on previous research regarding reactions to disadvantaged and advantaged targets, we examined the social cognitive underpinnings of support for gay rights. After accounting for general anti-gay attitudes and degree of religious affiliation, we found that global endorsement of just world beliefs negatively predicted support for gay rights, and that this effect was mediated by an inclination to perceive discrimination against gay and lesbian people as less of an issue in American society. Additionally, we found that endorsement of the ‘gay affluence’ stereotype also negatively predicted support of gay rights, particularly among non-student adults, and that this effect was moderated by character beliefs about gay and lesbian people pertaining to wealth-deservingness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In drafting our materials for the current project, we avoided bifurcation of the broader category of ‘gay’ people, because (at least in the realm of legal advocacy) GLAs must either succeed or fail together, and to the extent gay men are the more salient group when the category ‘gay’ is mentioned, that is largely reflective of the state of public discourse on this topic. It is assumed that many participants in our study considered only gay men when making their responses; however, it is unlikely that we could have measured the extent to which this occurred without introducing bias, and (in so far as it was reflective of the way people think about these issues on a daily basis) we do not feel it compromised the overarching goals of the project.

In the second pilot study, we also confirmed that the opposite pole to each of these traits {lazy, uncommitted, ignorant, stupid, low in perseverance, unimaginative, and dishonest} was indeed negatively associated with perceptions of wealth-deservingness.

Most college students do not yet have careers, or a substantial independent income, and the relevance/impact of their family’s socioeconomic status is blunted somewhat while in school.

The literature on the influence of race and ethnicity on attitudes toward gay and lesbian people is mixed, but most consistently suggests that White participants report more favorable attitudes, while Black/African American participants report more negative attitudes. Thus, for the present analysis, race was coded as two dummy variables: 1, 0 for White participants, 0, 1 for Black/African American participants, and 0, 0 for the remaining participants.

Correlations between all the variables of interest can be found in Appendix 2.

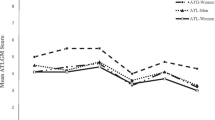

While both the student and non-student samples rated gay affluence significantly higher than the theoretical midpoint of 9.5 (aggregating the two scales, possible scores ranged from 2 to 17) the non-student sample did so by more than a point (M = 10.75, SD = 2.42), whereas the student sample did so by less than half a point (M = 9.94, SD = 2.16).

Following the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991), mean-centered versions of these variables were used, both in the computation of the interaction term and in the subsequent regression analysis, in order to reduce potential effects of collinearity.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpretation interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Badgett, M. V. L. (1998). Income inflation: The myth of affluence among gay, lesbian and bisexual Americans. Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, with The Institute for Gay and Lesbian Studies. Retrieved November 4, 2014, from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/IncomeInflationMyth.pdf.

Barrett, D. C., Pollack, L. M., & Tilden, M. L. (2002). Teenage sexual orientation, adult openness, and status attainment in gay males. Sociological Perspectives, 45, 163–182.

Becker, D. P. (1997). Growing up in two closets: Class and privilege in the lesbian and gay community. In S. Raffo (Ed.), Queerly classed (pp. 227–234). Boston: South End.

Bernard, T. S., & Lieber, R. (2009, October 2). The high price of being a gay couple. The New York Times. Retrieved November 4, 2014, from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/03/your-money/03money.html.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009). Gay stereotypes: The use of sexual orientation as a cue for gender-related attributes. Sex Roles, 61, 783–793.

Bouton, R., Gallaher, P., Garlinghouse, P., & Leal, T. (1987). Scales for measuring fear of AIDS and homophobia. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51, 606–614.

Brewer, P. R. (2003a). The shifting foundations of public opinion about gay rights. The Journal of Politics, 65, 1220–1298.

Brewer, P. R. (2003b). Values, political knowledge, and public opinion about gay rights: A framing-based account. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67, 173–201.

Brown, M. J., & Groscup, J. L. (2009). Homophobia and acceptance of stereotypes about gays and lesbians. Individual Differences Research, 7, 159–167.

Chasin, A. (2000). Selling out: The gay and lesbian movement goes to market. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Cikara, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). Stereotypes and schadenfreude: Affective and physiological markers of pleasure at outgroup misfortunes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 63–71.

Clausell, E., & Fiske, S. T. (2005). When do subgroup parts add up to the stereotypic whole? Mixed stereotype content for gay male subgroups explains overall ratings. Social Cognition, 23, 161–181.

Confessore, N. (2013). Pushing the G.O.P. to support gay rights. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/us/politics/pushing-the-gop-to-support-gay-rights.html?hp&_r=1&pagewanted=all&.

Czopp, A. M. (2008). When is a compliment not a compliment? Evaluating expressions of positive stereotypes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 413–420.

Employment Non-Discrimination Act. (1994). Hearings on S. 2238 Before the Senate Comm. on Labor and Human Resources, 103d Cong. 703 (1994), statement of Joseph Broadus, Family Research Council.

Ender, P. (2006). Parallel analysis for PCA and factor analysis. UCLA: Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group. Retrieved November 4, 2014, from http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/ado/analysis/.

Feather, N. T., & Sherman, R. (2002). Envy, resentment, schadenfreude, and sympathy: Reactions to deserved and undeserved achievement and subsequent failure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 953–961.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902.

Gallup Historical Trends. (2014). Gay and Lesbian Rights. Poll questions. Retrieved January 31, 2014, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1651/Gay-Lesbian-Rights.aspx.

Gaucher, D., Hafer, C. L., Kay, A. C., & Davidenko, N. (2010). Compensatory rationalizations and the resolution of everyday undeserved outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 109–118.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118.

Gluckman, A., & Reed, B. (1997). Homo economics: Capitalism, community, and lesbian and gay life. New York: Routledge.

Gross, L. (2001). Up from invisibility: Lesbians, gay men, and the media in America. New York: Columbia University Press.

Haider-Markel, D. P., & Joslyn, M. R. (2008). Beliefs about the origins of homosexuality and support for gay rights: An empirical test of attribution theory. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 291–310.

Hegarty, P. (2002). ‘It’s not a choice, it’s the way we’re built’: Symbolic beliefs about sexual orientation in the US and Britain. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 153–166.

Jost, J. T., & Burgess, D. (2000). Attitudinal ambivalence and the conflict between group and system justification motives in low status groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 293–305.

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2002). The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology. European Review of Social Psychology, 13, 111–153.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509.

Kay, A. C., Day, M. V., Zanna, M. P., & Nussbaum, A. D. (2013). The insidious (and ironic) effects of positive stereotypes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 287–291.

Kay, A. C., & Jost, J. T. (2003). Complementary justice: Effects of “poor but happy” and “poor but honest” stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 823–837.

Kay, A. C., Jost, J. T., & Young, S. (2005). Victim derogation and victim enhancement as alternate routes to system justification. Psychological Science, 16, 240–246.

Lerner, M. J. (2003). The justice motive: Where social psychologists found it, how they lost it, and why they may not find it again. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 388–399.

Lipkus, I. (1991). The construction and preliminary validation of a global belief in a just world scale and the exploratory analysis of the multidimensional belief in a just world scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 1171–1178.

Loftus, J. (2001). America’s liberalization in attitudes toward homosexuality, 1973–1998. American Sociological Review, 5, 762–782.

Morrison, T. G., & Bearden, A. G. (2007). The construction and validation of the homopositivity scale: An instrument measuring endorsement of positive stereotypes about gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 52, 63–89.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731.

Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, at 645-46, Scalia, J. dissenting (1996).

Romero, A. P., Baumle, A. K., Badgett M. V. L., & Gates, G. J. (2007). United States Census Snapshot. The Williams Institute: Policy Studies Publications, UCLA School of Law. http://www.law.ucla.edu/williamsinstitute/publications/USCensusSnapshot.pdf.

Salovey, P., & Rodin, J. (1984). Some antecedents and consequences of social-comparison jealousy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 780–792.

Sender, K. (2004). Business, not politics: The making of the gay market. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shugart, H. A. (2003). Reinventing gay male privilege: The new gay man in contemporary popular media. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 20, 67–91.

Siy, J. O., & Cheryan, S. (2013). When compliments fail to flatter: American individualism and responses to positive stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 87–102.

Socarides, R. (2013, March 28). Gay political power—Or good survival skills? The New Yorker. Retrieved November 4, 2014, from http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2013/03/gay-political-poweror-good-survival-skills.html.

Soule, T. (2006, April). The myth of gay affluence. Orange County Blade, 12–17.

StataCorp. (2005). Stata statistical software: release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Vandello, J. A., Goldschmied, N. P., & Richards, D. A. R. (2007). The appeal of the underdog. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1603–1616.

Walls, N. E. (2008a). Modern heterosexism and social dominance orientation: Do subdomains of heterosexism function as hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myths? In T. G. Morrison & M. A. Morrison (Eds.), The psychology of modern prejudice (pp. 225–259). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Walls, N. E. (2008b). Toward a multidimensional understanding of heterosexism: The changing nature of prejudicial attitudes. Journal of Homosexuality, 55, 20–70.

Walters, S. D. (2001). All the rage: The story of gay visibility in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Gay Rights Support Questionnaire

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Very unsupportive | Very supportive |

-

1)

How supportive would you be of a policy change which would allow gays to serve openly in the U.S. military?

-

2)

How supportive would you be of a change in national law which would allow gays to marry in every state?

-

3)

How supportive would you be of a law in your state allowing gays to marry?

-

4)

How supportive would you be of a change in national law which would officially recognize the marriages of gays whose marriages are legally recognized in their own state?

-

5)

How supportive would you be of a national law which would allow gays to adopt children in every state?

-

6)

How supportive would you be of a law in your state allowing gays to adopt children?

-

7)

How supportive would you be of a national law which would include gays as a protected group for purposes of employment discrimination?

-

8)

How supportive would you be of a law in your state which would include gays as a protected group for purposes of employment discrimination?

-

9)

How supportive would you be of a national law which would include gays as a protected group for all existing hate crimes legislation?

-

10)

How supportive would you be of a law in your state which would include gays as a protected group for all existing hate crimes legislation?

Note: From the time, this project was in the early development/piloting stages to the present, a number of positive advancements in the realm of LGBT advocacy have taken place. While we do not feel these developments negate what we were able to learn from this project, revision of this scale would be advisable for follow-up studies.

Appendix 2: Bivariate correlations among variables of interest

Sample | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Primary variables | |||||||||||||

1. Support | .07 | ||||||||||||

2. Affluence | .17** | .04 | |||||||||||

3. Character | −.07 | −.31*** | −.35*** | ||||||||||

4. JWB | −.10† | −.15* | −.07 | −.004 | |||||||||

5. Amnestic | .16** | −.41*** | .02 | .20** | .16** | ||||||||

Secondary/demographic variables | |||||||||||||

6. Homophobia | −.07 | −.82*** | −.15* | .37*** | .11† | .39*** | |||||||

7. Religiosity | −.01 | −.41*** | −.01 | .07 | −.02 | .14* | .42*** | ||||||

8. Sex | −.12* | −.09 | −.02 | .07 | .04 | .00 | .05 | −.19** | |||||

9. Age | .77*** | −.02 | .15* | −.12* | −.11† | .14* | .05 | .10† | −.16** | ||||

10. Political | .04 | −.36*** | .02 | .04 | .18** | .25*** | .34*** | .25*** | .01 | .09 | |||

11. Race (W) | .22*** | .09 | .14* | −.12* | −04 | −.02 | −.15* | −.11† | .06 | .21*** | .14* | ||

12. Race (B) | −.20** | −.10 | −.18** | .11† | −.07 | −.01 | .23*** | .12* | −.06 | −.16** | −.16** | −.56*** | |

13. Income | .16** | −.02 | .09 | −.04 | −.03 | −.04 | −.06 | .10 | .01 | .17** | .12† | .10 | −.16** |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hettinger, V.E., Vandello, J.A. Balance Without Equality: Just World Beliefs, the Gay Affluence Myth, and Support for Gay Rights. Soc Just Res 27, 444–463 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-014-0226-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-014-0226-2