Abstract

Cross-national health research devotes considerable attention to lifespan and survival rate disparities that are found between countries. However, the distribution of mortality across the world is shaped mostly by what happens within countries. We address this striking gap in the literature by modeling length-of-life inequality for individual nation-states. We use life tables from the United Nation’s (2015) World Population Prospects to estimate inequality levels for 200 countries across 13 waves between 1950 and 2015. We find that lifespan inequality is steadily declining across the world, but that each country’s level of inequality, and the rate at which it declines, vary considerably. Our models account for more than 90% of the longitudinal and cross-sectional variation in country-level lifespan inequality during the 1990–2015 period. Maternal mortality is the strongest predictor in our model, while disease prevalence, access to safe water, and health interventions figure prominently, as well. Gross domestic product per capita shows the expected curvilinear association with lifespan inequality, while primary education (both overall enrollment and gender equity in enrollment), external debt, and migration also play critical roles in shaping health outcomes. By contrast, the distribution of political and economic resources (i.e., democracy and income inequality) is less important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Gini produces estimates that are downwardly biased. This bias is greatest in small populations and dissipates rapidly with increases in the sample size. In particular, Gini’s downward bias is 10% when the sample is 10, but declines to 1% when the sample increases to 100, and drops to 0.1% when the sample reaches 1000 (Di Maio and Landoni 2015). Fortunately, our sample size is 100,000 for each country, making our downward bias .001% (i.e., 1/1000th of 1%). Several scholars propose an adjustment, replacing n2 with n*(n − 1) (Deaton 1997; Deltas 2003). However, we do not take this additional step (i.e., multiplying all our estimates by 1.00001), as the change in our results would be imperceptible.

Both the Gini and Theil can accommodate population weights applied to the mean (u), the sample size (n), as well as the number of actor-pairs (Gini) or number of ratios (Theil).

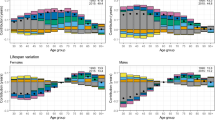

It is also possible to decompose lifespan inequality within each country by gender, as life tables are reported for both males and females in World Population Prospects. Past work shows that the mortality distribution across the world for males and females are quite similar (Smits and Monden 2009; Stromme and Norheim 2016) and that cross-national variation in lifespan inequality cannot be attributed to mortality differences across gender (Edwards and Tuljapurkar 2005). Nevertheless, we performed an auxiliary analysis to assess the contribution of gender to lifespan inequality within countries. To do so, we selected the five countries in our data with the largest gender gap in life expectancy for the most recent wave (2010–2015): Syria, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania, and Ukraine. In these countries, women are outliving men by about 10–12 years. We then calculated the mortality distribution for each country by merging the male and female life tables together. The between-gender contribution to each country’s lifespan inequality ranges from 6.4% (Ukraine) to 10.2% (Belarus). Thus, even in those states where the gender gap in mortality is greatest, gender only accounts for about 10% of the mortality distribution.

References

Allison, P. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. London: Sage Publications.

Anderson, F., Morton, S., Naik, S., & Gebrian, B. (2007). Maternal mortality and the consequences on infant and child survival in rural Haiti. Maternal and Child Health Journal,11, 395–401.

Babones, S. (2008). Income inequality and population health: Correlation and causality. Social Science and Medicine,66, 1614–1626.

Banda, R., Sandoy, I., Fylkesnes, K., & Janssen, F. (2015). Impact of pregnancy-related deaths on female life expectancy in Zambia: Application of life table techniques to census data. PLoS ONE,10, 1–17.

Beckfield, J. (2004). Does income inequality harm health? New cross-national evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,45, 231–248.

Besley, T., & Kudamatsu, M. (2006). Health and democracy. American Economic Review,96, 313–318.

Biggs, B., King, L., Basu, S., & Stuckler, D. (2010). Is wealthier always healthier? The impact of national income level, inequality, and poverty on public health in Latin America. Social Science and Medicine,71, 266–273.

Blaydes, L., & Kayser, M. (2011). Counting calories: Democracy and distribution in the developing world. International Studies Quarterly,55, 887–908.

Boehmer, U., & Williamson, J. (1996). The impact of women’s status on infant mortality rate: A cross-national analysis. Social Indicators Research,37, 333–360.

Brady, D., Kaya, Y., & Beckfield, J. (2007). Reassessing the effect of economic growth on well-being in less-developed countries, 1980–2003. Studies in Comparative International Development,42, 1–35.

Bulled, N., & Sosis, R. (2010). Examining the relationship between life expectancy, reproduction, and educational attainment. Human Nature,21, 269–289.

Clark, R. (2011). World health inequality: Convergence, divergence, and development. Social Science and Medicine,72, 617–624.

Deaton, A. (1997). The analysis of household surveys: A microeconometric approach to development policy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the gallup world poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives,22, 53–72.

Deltas, G. (2003). The small-sample bias of the Gini coefficient: Results and implications for empirical research. Review of Economics and Statistics,85, 226–234.

Di Maio, G., & Landoni, P. (2015). Beyond the Gini index: Measuring inequality with the balance of inequality index. Working Papers Series 1506. Italian Association for the Study of Economic Asymmetries.

Easterlin, R. (2000). The worldwide standard of living since 1800. Journal of Economic Perspectives,14, 7–26.

Edwards, R. (2011). Changes in world inequality in length of life: 1970–2000. Population and Development Review,37, 499–528.

Edwards, R. (2013). The cost of uncertain life span. Journal of Population Economics,26, 1485–1522.

Edwards, R., & Tuljapurkar, S. (2005). Inequality in life spans and a new perspective on mortality convergence across industrialized countries. Population and Development Review,31, 645–674.

Fields, G. (2001). Distribution and development: A new look at the developing world. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Firebaugh, G. (2003). The new geography of global income inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Firebaugh, G., & Beck, F. (1994). Does economic growth benefit the masses? Growth, dependence, and welfare in the third world. American Sociological Review,59, 631–653.

Franco, A., Alvarez-Dardet, C., & Ruiz, M. (2004). Effect of democracy on health: Ecological study. British Medical Journal,329, 1421–1423.

Frey, R. Scott, & Field, C. (2000). The determinants of infant mortality in the less developed countries: A cross-national test of five theories. Social Indicators Research,52, 215–234.

Gakidou, E., & King, G. (2002). Measuring total health inequality: Adding individual variation to group-level differences. International Journal for Equity in Health,1, 1–12.

Gillespie, D., Trotter, M., & Tuljapurkar, S. (2014). Divergence in age patterns of mortality change drives international divergence in lifespan inequality. Demography,51, 1003–1017.

Global Burden of Disease. (2014). Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet,384, 980–1004.

Global Burden of Disease. (2016). Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet,388, 1459–1544.

Gravelle, H., Wildman, J., & Sutton, M. (2002). Income, income inequality, and health: What can we learn from aggregate data? Social Science and Medicine,54, 577–589.

Greene, W. (2008). Econometric analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hauck, K., Martin, S., & Smith, P. (2016). Priorities for action on the social determinants of health: Empirical evidence on the strongest associations with life expectancy in 54 low-income countries, 1990–2012. Social Science and Medicine,167, 88–98.

International Organization for Migration. (2013). World migration report 2013. Grand-Saconnex: International Organization for Migration.

Kennedy, S., Kidd, M., McDonald, J., & Biddle, N. (2015). The healthy immigrant effect: Patterns and evidence from four countries. International Migration and Integration,16, 317–332.

Marshall, M. (2016). Major episodes of political violence (MEPV) and conflict regions, 1946–2015. Retrieved July 2016, from http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

Marshall, M., Gurr, T., & Jaggers, K. (2016). Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2015. Retrieved July 2016, from http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

Milanovic, B. (2005). Worlds apart: Measuring international and global inequality. Cambridge: Princeton University Press.

Neumayer, E., & Plumper, T. (2016). Inequalities of income and inequalities of longevity: A cross-country study. American Journal of Public Health,106, 160–165.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica,49, 1417–1426.

Nielsen, F., & Alderson, A. (1995). Income inequality, development, and dualism: Results from an unbalanced cross-national panel. American Sociological Review,60, 674–701.

Nooruddin, I., & Simmons, J. (2006). The politics of hard choices: IMF programs and government spending. International Organization,60, 1001–1033.

Pandolfelli, L., Shandra, J., & Tyagi, J. (2014). The International Monetary Fund, structural adjustment, and women’s health: A cross-national analysis of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sociological Quarterly,55, 119–142.

Pradhan, M., Sahn, D., & Younger, S. (2003). Decomposing world health inequality. Journal of Health Economics,22, 271–293.

Pritchett, L. (1997). Divergence, big time. Journal of Economic Perspectives,11, 3–17.

Pritchett, L., & Summers, L. (1996). Wealthier is healthier. Journal of Human Resources,31, 841–868.

Ram, R. (2006). Further examination of the cross-country association between income inequality and population health. Social Science and Medicine,62, 779–791.

Scanlan, S. (2010). Gender, development, and HIV/AIDS: Implications for child mortality in less developed countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology,51, 211–232.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Shandra, J., Nobles, J., London, B., & Williamson, J. (2005). Multinational corporations, democracy, and child mortality: A quantitative, cross-national analysis of developing countries. Social Indicators Research,73, 267–293.

Shandra, C., Shandra, J., Shircliff, E., & London, B. (2010). The International Monetary Fund and child mortality: A cross-national analysis of Sub-Saharan Africa. International Review of Modern Sociology,36, 169–193.

Shen, C., & Williamson, J. (1997). Child mortality, women’s status, economic dependency, and state strength: A cross-national study of less developed countries. Social Forces,76, 667–700.

Shen, C., & Williamson, J. (2001). Accounting for cross-national differences in infant mortality decline (1965–1991) among less developed countries: Effects of women’s status, economic dependency, and state strength. Social Indicators Research,53, 257–288.

Shkolnikov, V., Andreev, E., & Begun, A. (2003). Gini coefficient as a life table function: Computation from discrete data, decomposition of differences, and empirical examples. Demographic Research,8, 305–358.

Shkolnikov, V., Andreev, E., Zhang, Z., Oeppen, J., & Vaupel, J. (2011). Losses of expected lifetime in the United States and other developed countries: Methods and empirical analyses. Demography,48, 211–239.

Smits, J., & Monden, C. (2009). Length of life inequality around the globe. Social Science and Medicine,68, 1114–1123.

Solt, F. (2016). The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly,97, 1267–1281.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2013). Subjective well-being and income: Is there any evidence of satiation? American Economic Review,103, 598–604.

Stokes, R., & Anderson, A. (1990). Disarticulation and human welfare in less developed countries. American Sociological Review,55, 63–74.

Stromme, E., & Norheim, O. (2016). Global health inequality: Comparing inequality-adjusted life expectancy over time. Public Health Ethics,phw033, 1–24.

Subbarao, K., & Raney, L. (1995). Social gains from female education: A cross-national study. Economic Development and Cultural Change,44, 105–128.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2017). UNCTADstat. Retrieved July 2017, from http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/Index.html.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2017). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2016. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

United Nations Statistics Division. (2017). Demographic and social statistics: Civil registration and vital statistics. Retrieved August 2018, from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/crvs/#coverage.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2015). World population prospects: The 2015 revision. San Francisco: United Nations.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2016). International migration report 2015: Highlights. San Francisco: United Nations.

Waldmann, R. (1992). Income distribution and infant mortality. Quarterly Journal of Economics,107, 1283–1302.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2006). Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine,62, 1768–1784.

Wimberley, D. (1990). Investment dependence and alternative explanations of third world mortality: A cross-national study. American Sociological Review,55, 75–91.

World Bank. (2016). World development indicators. Retrieved July 2016, from http://data.worldbank.org.

World Health Organization. (2015). World health statistics 2015. Washington, DC: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2018). Civil registration coverage of cause-of-death. Retrieved August 2018, from http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.WHS10_8?lang=en.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amy Kroska, Martin Piotrowski, and Cyrus Schleifer for their generous assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, R., Snawder, K. A Cross-National Analysis of Lifespan Inequality, 1950–2015: Examining the Distribution of Mortality Within Countries. Soc Indic Res 148, 705–732 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02216-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02216-7