Abstract

Research examining the effects of spinal cord injury on sexuality has largely focused on physiological functioning and quantification of dysfunction following injury. This paper reports a systematic review of qualitative research that focused on the views and experiences of people with spinal cord injury on sex and relationships. The review addressed the following research question: What are the views and experiences of people with spinal cord injury of sex, sexuality and relationships following injury? Five databases were relevant and employed in the review: CINAHL (1989–2016 only), PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science, for research published between 1 January 1980 and 30 November 2019. After removing duplicates, 257 records remained and were screened using a two-stage approach to inclusion and quality appraisal. Following screening, 27 met the criteria for inclusion and are reported in the paper. The review includes studies from fifteen countries across five continents. Two main approaches to data analysis summary and thematic synthesis were undertaken to analyze the qualitative data reported in the papers. The analysis revealed four main themes: sexual identity; significant and generalized others, sexual embodiment; and; sexual rehabilitation and education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and Background

Spinal cord injury is an injury between the foramen magnum to the cauda equine, caused by traumatic injury [1] or spinal cord damage i.e. non traumatic injury or dysfunction to the spinal cord (for example through tumors or illness [2]. A recent systematic review suggests that the most common cause of spinal cord injury are motor vehicle accidents and falls [3], although data varies by geographical location [1]. Approximately 40 million people worldwide annually are affected by spinal cord injury [1]. The prevalence of spinal cord injury internationally is estimated to be 23 cases per million [4]; 10.4–83 cases per million for traumatic spinal cord injury [5]). Typically, spinal cord injury affects mostly men (80% in comparison to women, 20%) [6], with young men aged between 15 and 30 [4] or 20–35 [1] most affected. However, research evidence suggests that the average age at injury is increasing [5,6,7].

Research has primarily focused on men and less is known about women following spinal cord injury [8]. Women are often excluded from research because they represent a small sample size or because the noted effects of spinal cord injury for women vary markedly from men [8]. Most research has focused on physiological functioning and quantitative measurement, particularly ejaculatory dysfunction and other physiological issues [3]. Research evidence suggests that sexual dysfunction and infertility are common outcomes of spinal cord injury in men [4] whereas evidence suggests that women’s ability to get pregnant and carry a child is often unaffected by spinal cord injury [8]. The assumption is that women’s sexuality is unaffected by the injury [8]. Research often focusses on a medicalised view of reproduction and copulation, particularly physiologically, which overlooks the complex and multifaceted biopsychosocial nature of copulation as physiological, psychological and relational [6, 9].

Hocaloski et al. [9] outlined a sequalae of effects of spinal cord injury that reflects the multifaceted nature of sex and sexuality to describe primary, secondary and tertiary effects. Primary effects are from the physical impact of the injury, such as erectile dysfunction [10]. Secondary effects arise from indirect factors associated with spinal cord injury such as fatigue, discomfort and bladder and bowel issues. Bladder and bowel dysfunction is a commonly reported concern for people with a spinal cord injury and research strongly suggests that these impact on an individual physically and psychologically [11]. Tertiary factors include individual’s identity and body image. In a large survey 83% of men and women who had a spinal cord injury felt that the injury ‘altered their sexual sense of self’ [11]. Most studies report a decrease in sexual desire following injury [6] and that most men and women are less sexually active after spinal cord injury [6] because of lack of desire and/or lack of a partner.

In comparison to other aspects of spinal cord injuries, sexuality is considered under-studied, particularly in relation to the psychological and/or social aspects [8, 12]. However research suggests that spinal cord injury has an impact on all aspects of an individual’s sexuality: their bodily functions, psychology and identity as well as relationships with sexual partners [6]. Concerns about sex are reported as a primary concern for people with a spinal cord injury [6]. Regaining sexual functioning is often seen by people affected by a spinal cord injury to be an integral aspect of their quality of life and rehabilitation [1, 11].

Education about sexuality and sex following spinal cord injury is rare in rehabilitation [4] and often stigmatized [12]. Research has suggested that physicians and other practitioners are uncomfortable with raising the topic [13] or lack knowledge to effectively provide information about sex and spinal cord injury [14]. Practitioners may consider other aspects of recovery and management, such as information about bladder and bowel functioning, to be the most important aspect of post discharge education [14].

In summary, previous research has often focused on a medicalised approach to spinal cord injury, framing issues concerning sex within the context of physiological change and dysfunction. The focus on physiology and quantification of injury has led to a lack of research that has examined individuals’ experiences of spinal cord injury with a specific focus on subjective experience, particularly in which sexuality is treated as a multifaceted and central aspect of individuals’ identity [3]. This paper aims to examine the research field that to date has focused on these overlooked aspects of spinal cord injury, first-hand experience through qualitative research. The review focused on addressing the following research question: What are the views and experiences of people with spinal cord injury of sex, sexuality and relationships following injury?

Methods

Identification of Studies

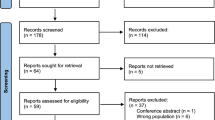

A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the qualitative literature on sex and relationships following spinal cord injury was carried out between July and November 2019, using a combination of search strategies to maximize identification of relevant studies. The aim of this review was to explore the views and experiences on sex and relationships following spinal cord injury, focusing on adults living with spinal cord injury and including both men and women. Following advice from a data information specialist regarding appropriate database selection, database searching via the five following databases was conducted to find material published between 1st January 1980 and 30th November 2019: CINAHL (1989–2016 only), PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science (for search terms see Table 1). The search strategy for one database is detailed in Fig. 1; similar strategies were adopted across the other databases. Manual searches were also carried out using the citations of the selected studies to identify further papers. The grey literature was also searched using Google (first 100 hits) and specialist sites that might contain information on sexuality and spinal cord injury (i.e. Aspire, Back Up Trust, BASIC Charity, Nicholls Spinal Injury Foundation, Southern Spinal Injuries Trust, Spinal Injuries Association, Spinal Injuries Scotland, Spinal Research).

Selection of Studies

Papers were selected for inclusion if they reported the views and experiences of persons with spinal cord injury on sex and relationships and if they reported original qualitative data. Given database restrictions, the systematic review was restricted to studies published between 1 January 1980 and 30 November 2019. Studies published in languages other than English and Spanish were excluded as they could not be translated by the project team. Studies that wholly or predominantly reported the views and experiences of young people were also excluded since the study sought to focus on adults with spinal cord injury.

The project team met monthly to discuss the study. Author 1 conducted the database searches and manually searched citations. Author 1 also conducted the manual search of other sources. Paper titles and abstracts were also screened by Author 1, who identified papers that did not meet inclusion criteria and removed duplicates; Author 2 checked titles and abstracts independently and agreed whether papers met criteria for inclusion. Eligible papers were shortlisted and authors 1 and 2 individually assessed full-text articles separately, using a data extraction form, and then met to discuss their reasoning. Any discrepancies (n5) were dealt between them and there were no differences in judgement. All decisions were discussed and agreed within the whole project team.

Quality Appraisal

Quality appraisal of the selected studies was conducted initially by authors 3 and 4 following the method described by Walsh and Downe [15], a method that applies criteria intended to be used reflexively and in the context of a qualitative research tradition. Walsh and Downe suggest using criteria to give an indication of research quality but without using checklists, ratings or scoring. Adopting this method of quality of appraisal, data were extracted by authors 3 and 4 on the following: Scope and purpose of study; study design; sampling strategy; analysis; interpretive framework; issues relating to reflexivity; issues relating to ethics; the relevance and transferability of the study; and, a narrative summary of the study quality (see Online Resource 1). Authors 1 and 2 read the quality appraisal for each paper and made suggestions for additions or amendments which were discussed and agreed within the whole project team. None of the studies were excluded from the review based on the quality appraisal although it was used reflexively to provide additional context for data analysis.

Data Summary and Synthesis

We used two main approaches to analyze the data: summary and thematic synthesis. First, we summarized each paper to describe the key characteristics of the included studies (see Table 2). Second, using a method of thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke [16], and the process of constant comparison outlined by Lincoln and Guba [17], the data were analyzed inductively to produce a narrative synthesis of the views and experiences of sex, sexuality and relationships following spinal cord injury. There are a number of different methods that can be used in the systematic review of qualitative studies [18]. In this instance we used the findings, discussion and conclusion sections of each paper and the primary data (quotes) contained therein to carry out line-by-line coding. We also used QSR NVivo 12 for Mac, a qualitative data analysis software package, to assist with analysis. Authors 1 and 2 read the selected studies and then analyzed inductively, generating 75 initial codes. These initial codes were discussed and then using a dynamic process of constant comparison, or ‘going back and forth’ (p. 342) [17], the codes were reviewed and some of them were collapsed. After completing this process, 43 codes remained. The codes were then grouped into descriptive categories and compared for completeness and robustness. At this stage some of the categories were collapsed and some codes were moved between categories. In the final stage of analysis, the categories were grouped into four main analytical themes as described in the findings below. Drawing on the work of Thomas and Harden [18] we argue that while the line-by-line coding and the descriptive categories remain ‘close’ to the primary studies included in the review, the analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation that goes some way beyond this while still remaining rooted in the data.

Findings

We identified a total of 342 records through database searching and an additional 4 items were identified through other sources. After removing duplicates, 257 records remained and were screened. Following screening, 76 full-text papers were read to assess for eligibility. Of the 76 papers assessed, 27 met the criteria for inclusion (see Fig. 2). Forty-nine papers were excluded: 24 did not focus on sex and/or experiences of people with SCI; 17 did not report qualitative data; four reported data already published elsewhere; three were not published in English or Spanish and, one focused solely on young people (see Online Resource 2). The included papers were based on three types data collection methods: interviews (n25), questionnaires (n3) and surveys (n2) and provided data for 1010 people with SCI (290 men and 720 women); four papers used mixed methods [19,20,21,22]. The majority of papers were based on studies that only included women (n16), six papers reported studies based on men only and five on studies that included both women and men. This review includes papers from fifteen countries across five continents. The greatest proportion of papers were based in the USA (n9), four were based in Australia, three in the UK, two in Greece, Iran and Sweden respectively, and one each in Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, Iceland, India, Norway and South Africa. All but one paper collected data within a single country only except for Kreuter et al. [23] which collected data from 5 Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden). The earliest paper [19] was published in 1984 and was the only paper to be published in the 1980s; three papers were published in the 1990s, nine papers in the 2000s and 14 papers since 2010. In three cases, we found more than one paper pertaining to the same study. After careful reading, papers were only selected for inclusion if they reported sufficiently different qualitative data to warrant separate analysis. Papers from the same study that reported the same or similar data were excluded for that reason. In the first case, we found three papers pertaining to the same study; excluded one and included two [24, 25]. In the second case, we found four papers pertaining to the same study; we excluded two and included two [26, 27]. In the third case we identified two similar papers and included one [28].

Our analysis of the 27 included papers, representing data from 25 studies, revealed four main themes: sexual identity; significant and generalized others, sexual embodiment; and; sexual rehabilitation and education.

Sexual Identity

Of the 27 papers reviewed, 21 papers addressed the issue of sexual identity, and six did not [22, 27, 29, 30,31,32]. Of the 21 papers, two papers focused specifically on exploring identity as one of their main research aims [33, 34]. The majority of papers reviewed referred to identity but did not theorize it. Understandings of identity vary and are dependent upon one’s disciplinary perspective but in very general terms it refers to one’s sense of self [35,36,37,38,]. Sexual identity contributes to a sense of self and the papers reviewed touched on various aspects of sexual identity including intimacy, sex, reproduction, gender identity and (rarely) sexual orientation. Twelve papers [20, 22, 24, 25, 31, 36,37,38,39,40] identified the sexual orientation of their research participants; of the remaining 15 papers, heteronormativity was implied but not referred to explicitly.

The majority of papers that addressed sexual identity identified sex and sexuality to be an important part of identity post-injury. In the paper by Seddon et al. [32] participants said that regaining some level of sexual expression after injury made them feel ‘normal’. Sex was considered an important part of life and individuals said that they were, or wanted to be, sexually active [23, 28, 32, 36, 37, 41, 42]. Indeed, Cramp et al. [36] report that sex was one of the first issues that most women inquired about following their injury and, according to Chapple et al. [41], sexual activity was seen as especially important in maintaining intimacy with a partner. Other studies suggest that sex was more important for some people than for others, and that a range of factors influence the significance of a person’s sexual identity including age, illness and other disabilities [32, 41].

Sexuality is an important part of ‘doing gender’; that is, of being and feeling like a man or a woman [8, 9]. However, in one study, a participant describes the effects of SCI as ‘desexualizing’ [41]. The literature suggests that SCI can have a profound effect on an individual’s ability to feel masculine or feminine although it also suggests that there may be subtle differences in the way that this manifests according to gender. For men, a loss of independence was proportional to a loss of masculinity, with subsequent corollaries for sexual identity. For example, in the study by Basson et al. [43] men spoke about how difficult it was to manage a loss of independence and struggled with their reliance on a (female) partner for everyday tasks:

The physical things like not being able to drive. That your wife has to drive for you. Drive you where you want to go. She has to load you in the car. She orders at the restaurant. She pays the bill…. (p. 8) [43]

In another study [26], men spoke more about the impact of loss of independence, highlighting further the relationship between independence, masculinity and sexual identity:

It is an issue that bothers me, when I have to ask a girl to help me with taking off my pants, because manhood is directly associated with having sex… (p. 103) [26]

Women experienced similar losses to men following SCI and they too drew a connection between sex, sexual identity and feelings of femininity [24, 25, 33, 37, 38]. Indeed, in one study the experience of SCI was described as ‘taking away’ a person’s ‘womanhood’ [37]. Engaging in sexual activity was often pivotal in regaining a sense of self and rediscovering a sense of feminine identity post-injury:

I decided I was human, I was a woman and I needed to prove my identity as a woman so I went out and sought myself a casual fuck. It felt good… rotten actually because I’d never had casual sex before, but good that I could go out and get it. (p. 320) [33]

I got back to every other aspect of my life other than that [sex] after injury… I went back to teaching full time… I drove my car… everything was in its place except for my liking myself and my sexuality, and feeling like I was a woman again… and that took me fifteen years to go to that point. (p. 279) [38]

Five of the studies suggest that women’s sexual identity was also connected to reproductive capacity and to women’s traditional roles as wives and mothers; these studies were conducted in the USA, Hong Kong, China, Iran and Australia respectively [21, 31, 32, 37, 44]. Women’s experiences were generally framed within the cultural norms about gender and sexuality. For example, in the study by Li and Yau [44] women said that SCI made them feel invisible as mothers and wives when, post-injury, they were unable to perform housework or caring duties. Being able to bear a child, they said, made them feel ‘more like a woman’ (p. 13). In another study, a participant describes how knowing whether she could have children, and become a mother, was more important than being able to walk:

I know one of my greatest concerns right after my injury wasn’t so much about walking but whether I could be a mother or not. And I think that would be another interesting study…. I remember asking the doctor [physician], “Can I still have children?” To me, that was far more important than being able to get back on my legs. (p. 6) [37]

Maintaining or establishing sex, intimacy and relationships post-injury was an important part of everyday life for most people with SCI. Sex and sexuality was also an important part of gender identity although this manifested itself in different ways for women and men. People with SCI often felt ‘desexualized’ following injury and acknowledging their sexual identity could be an important part of recovery.

Significant and Generalized Others

How individuals felt about themselves was often strongly influenced by others. Just over half of the papers we reviewed (n15) explored issues relating to sexuality and significant or generalized others. We use the term ‘significant other’ to describe husbands, wives, partners, boyfriends or similar and ‘generalized other’ to describe references made to society in general or, as Basson et al. [43] describe it, ‘society at large’.

The literature suggests that the attitudes of significant others are really important, regardless of whether those relationships are positive or negative. Some participants reported negative experiences post-injury with respect to existing relationships with significant others [19, 20, 24, 28, 30, 44, 45]. For example:

What do they call the people that make love to dead bodies? Necrophiliac? Well, that’s what my ex-husband used to say, “Oh, I’m not a necrophiliac”. (p. 71) [28]

My relationship with my wife is not like before as I am not like other men and cannot perform sexual activities. She has distress. It is not like before, her love has decreased. However, I have to bear with my wife and learn to adjust (p. 16) [30]

In some instances, negative attitudes post-injury seemed to contribute directly to relationship breakdown, particularly for women. The loss of sexual function was described as ‘the beginning of the end’ (p. 620) [39]. In the study by Li and Yau [44] participants said:

Before our divorce, we had some arguments over sex. I always felt that I had already satisfied him but he felt that we never had sex. I think he may be right. I know I have emotionally shut down my desire. Once he forced himself on me, I felt like I was being raped and I could never forgive him for such behavior. (p. 15) [44]

…traditional Chinese men still expect their wives to take up all of the domestic chores and nurturing at home. So, it is very difficult for them to take on the converse caring role. In view of this situation, I agreed to a separation and he accepted immediately. I also decided to live in an institution for the rest of my life. (p. 10) [44]

However, not all post-injury relationship breakdown was perceived as negative. In cases where the relationship was already problematic, relationship breakdown following SCI was sometimes, retrospectively, seen as a positive life change [24]. Where relationships with significant others were positive, being able to communicate as openly as possible, and having a partner that was understanding, were seen as essential components of managing sexuality post-injury [32, 33, 42]. For example, one the of the participants in the study by Seddon et al. [32]) said:

My partner’s] been fantastic in saying he still loves me and he still wants to have a sort of a sexual interaction, he still finds my body attractive, and that’s been wonderful. That has been so good. I just have to be so thankful that he’s still here, and he really still loves me madly and is so helpful. (p. 292) [32]

Not all discussion in the literature focused on intimate personal relationships. There was also a focus on a ‘generalized other’, often referred to as ‘society’ or ‘other people’. The generalized other was perceived by participants has having negative attitudes towards SCI and the disabled body, positioning people with SCIs as asexual, unwanted and unattractive [24, 26, 32,33,34, 37, 40]. These ideas then appear to be internalized in what has been identified by Shakespeare [46] as ‘internalized othering’. A female participant in the study by Parker and Yau [34] states:

You think that because you are in a wheelchair that nobody will want you… You have still got feelings and you still want to experience your sexuality. But they [society and potential romantic partners] don’t see you like that, because you are in a wheelchair. Which makes it very hard because you still feel like a woman. (p. 21) [34]

For individuals who were not in a relationship or for those whose relationships had broken down, the idea of finding a new intimate relationship could be quite daunting because ‘society’ was seen to perceive SCI negatively:

I thought I’d never have a relationship again. I thought I’d never have sex again. And finding somebody who is sensitive enough to be there for the need is a challenge. And you have to have enough confidence to allow yourself to go there, too, so I have to be all right with me in order for people to be all right with me. You know, ‘cause the shock value when they see you, it’s like, “Oooh… myyy… God, she’s so pitiful,” you know? (p. 7) [37]

Our analysis of the literature indicates that the attitudes (and perceived attitudes) of others can influence views and experiences of sexuality and SCI. While some experiences are positive, in that participants report experiences of happy and supportive relationships, other people report negative experiences suggesting that SCI can lead to relationship breakdown. For individuals not in a relationship, the idea of pursuing a new sexual relationship was seen as daunting either because of actual or imagined negative societal attitudes towards people with disabilities.

Sexual Embodiment

The theme of sexual embodiment was addressed by all but five [21, 22, 29, 40, 45] of the papers reviewed. To be embodied refers to the feelings and sensations that are experienced of being in one’s body [47]. To be sexual is predominantly an embodied experience in that sexuality is experienced through and within one’s own body and enacted with the bodies of other people. Our analysis of the papers highlights how narratives of embodiment focused on comparisons of sexuality before and after injury with two distinct narratives being evident. In the first narrative, post-injury embodiment is found to constrain or prevent sexual activity or sexual pleasure. Fourteen of the papers described findings where participants spoke about sexual difficulties and sexual dissatisfaction post-injury [23,24,25, 28, 30, 31, 34, 36,37,38, 40,41,42, 44]. Significant difficulties included feelings of discomfort and pain, as well as lack of sensation and, consequently, sexual pleasure. For example:

Men discussed not being able to achieve an erection, and men and women both talked about not being able to orgasm [23, 30,31,32, 36, 38, 40]. Some research participants also talked about how their injury made it difficult to find suitable sexual positions. For example, in the study by Cramp et al. [36] one participant reported having sex ‘anyplace, anywhere’ and ‘in all sorts of positions’ before injury whereas they reported only having sex on a bed after injury because it is what worked ‘logistically’. Participants also spoke about missing sexual spontaneity:

The whole spontaneity thing has gone out of the door because everything is planned… I can’t get up and run to him and give him a cuddle, or if he has got his back to me somewhere I can’t just go up to him and give him a cuddle and a kiss. I can come up to him, but it is predictable, because I am there. So it is not a surprise and it is not spontaneous. (p. 22) [34]

Twelve of the papers we reviewed referred specifically to the management of bladder and bowels as something that affected sex negatively [23,24,25, 28, 30,31,32, 36,37,38, 41, 44]. Many of the research participants expressed fear of losing control of their bladder or bowels during sex, preventing many individuals from engaging in sexual activity with another person. For example,

My big problem for having sex… I have urinary incontinence and sometimes, fecal incontinence (p. 317) [31]

Some individuals had waited several years prior to engaging in sexual activity (if at all)—even though sex was important to them—and a reluctance to re-engage with their sexual lives was often attributed to concerns with bladder and bowel management. Loss of control over bladder and bowels was seen as embarrassing and something fearful in the context of all sexual activity but particularly so in relation to sexual relations with a new partner:

It was 8 years later before [I had sex again], and I really wrestled with that. It wasn’t because I didn’t want to. It was because I didn’t think a guy would be interested in having sex with me, and then I was dealing with complications like bladder management problems. When you’re engaging in something like that and your bladder just lets out, or your bowels, you know, it’s embarrassing! (p. 5) [37]

… and another thing that worries me. Say you WAS to go to bed with somebody, and what if you pee all over them, you know? How are THEY gonna react, ‘cause I have no control over that. (p. 92) [25]

While many papers discussed the negative aspects of sexuality post-injury, other papers explored post-injury embodiment as an opportunity for the development of more positive sexual expression; fifteen of the papers reviewed fell into this category [20, 23,24,25, 27, 28, 30, 33, 34, 36, 38, 39, 42,43,44]. The study by Tepper [39] provides a good summary of this where she argues that post-injury individuals can engage in a process of sexual discovery and rediscovery to learn a ‘new way of being normal’. For some individuals, a new ‘normal’ means that, because physical sensation might be lost or diminished, the mind becomes more important than the body. Three papers explored this issue [24, 42, 43] and one individual describes it as:

Well, sexuality definitely means something to me different than it did before my accident… Now I think that it means not only a sexual act, but it actually means the feelings you have, and how you express yourself. I think it’s… how you see yourself as a person… how you feel about yourself. It’s… a whole lot more mental than I ever thought it was… (p. 73) [24]

For these individuals open and honest communication with partners was particularly important and felt to have a positive impact on relationships post-injury. In some instances, individuals talked about how they had learned to value emotional intimacy and closeness over and above the physical act of sex, for example:

I guess it comes down to being close, not so much the act itself. (p. 314) [42]

For other individuals, post-injury sex focused more on physical forms of sexual embodiment and experimentation, with new types of sexual pleasure and techniques being used. In some instances, this involved exploring elements of physical embodiment that had previously been less important or ignored, for example, the discovery of new erogenous zones. One female participant reported:

My nipples are actually the borderline, so they are very sensitive [and are incorporated into sexual expression]. (p. 19) [34]

In other papers, individuals spoke about engaging in more foreplay, or using fantasy and role play [23]. Some individuals reported using pornography [44] and sexual aids (e.g. vibrators and dildos) [23], as well as experimenting with more aggressive forms of sex. For example:

I’d definitely say that I like more aggressive sex now, things like slapping and stuff like that. It’s almost as if I can actually feel it and I just, I love the fact that I can feel it… (p. 406) [36]

Some of the papers also reported how men began to focus more on their (female) partner’s pleasure rather than their own, for example:

I cannot give sexual satisfaction to my wife (through vaginal intercourse) so I use other methods to satisfy her.’(p. 17) [30]

… because of my current situation I get to spend more time on my partner in bed. You know, we, guys, are a bit selfish. Our first worry is to get satisfaction ourselves. I don’t care about that anymore, especially since I know there’s not going to be any ejaculation. (p. 193) [27]

The review of the literature shows that spinal cord injury can have a profound effect on sexual embodiment. Pain, discomfort and a lack of sensation, including the inability to achieve erection or orgasm can seriously affect sexual expression. A fear of losing control of bladder and bowels during sex is also an important factor in whether an individual feels able to engage in sexual activity at all with another person. However, although accounts of sexual embodiment before and after injury often focus on loss, the literature also reveals many accounts of positive sexual expression framed by new opportunities to rethink what it means to be sexual.

Sexual Rehabilitation and Education

Eight papers specifically examined the subject of sexual rehabilitation and education [21, 22, 29, 33, 40, 41, 44, 48] and a further ten papers explored this in more general terms [20, 24,25,26, 28, 31, 34, 36, 37, 45]. Overall, the literature suggests a general dissatisfaction with sexual rehabilitation and sex education for people with SCI.

The literature focuses on who is best placed to deliver sex education. Two papers suggest that peer-support might be useful [34, 48] in that it allows individuals to speak with someone in a similar position who would not be judgmental. As one participant articulates:

I think it is better having someone who has been through it, rather than an able-bodied person. Because you know they have been through similar experiences and you can talk about things that might have been embarrassing and they are not going to judge you. Not necessarily that other people would, but you are a bit self-conscious about it. (p. 19) [34]

However, the majority of papers within the review focus on the role of professionals in delivering sex education and sexual rehabilitation indicating that some individuals prefer to be supported by ‘trained experts’ [10] rather than by their peers. Ideally, professional staff would be: ‘someone you could ask anything of, and they would be totally matter of fact and not make you feel embarrassed.’ [p. 5] [22]. Unfortunately, most people’s experiences seem to be quite far from this ideal. One paper describes the lack of sex education leaving women feeling ‘afraid and without hope’ [33]. The papers we reviewed suggest that some professionals seemed to ignore the issue of sex during rehabilitation [22, 28, 34, 41] and when the subject could not be ignored, they either found it embarrassing and uncomfortable [22, 48] or dealt with it badly [33, 36, 41]. Participants felt that professionals should be able to talk confidently and knowledgeably about sex to allow for sexuality to be a significant aspect of their lives. This was an important part of normalizing sex for people with SCI. For example:

I think sometimes they’re uncomfortable talking about things like that. They’re sort of, “Oh let’s push it under the carpet”, sort of thing. People need to be a bit more open about things like that. […] if you are open, sexuality is part of everyday life, it’s about who you are and what you are. (p. 1091) [48]

In some instances, sex education was non-existent or very limited, but even when it did exist, this review suggests that sexual rehabilitation and sex education for people with SCI is low quality and was described as unhelpful or dated. To remedy this, some individuals sought out their own information, via the internet, with mixed results:

During my rehabilitation period, I received some information about the negative impact of disability on sexual relationship. However, the information seemed not to have been updated. Conversely, the information I received from the internet is quite comprehensive and useful. It helps me to understand myself much better. (p. 16) [44]

I never really had anybody start up a conversation about it or really discuss it at all. What I learned pretty much learned on my own from researching on the Internet where I could find it. But even then, there wasn’t really a lot of information out there to find. (p. 28) [40]

There was discussion as to whether sex education should be delivered on a one-to-one basis or in groups and whether partners or other family members should be involved. One paper specifically identified a lack of information for partners [36] and two further papers highlighted the importance of providing support to couples, and not just to the person with the injury [34, 45].

In addition to dissatisfaction with the quality of materials used and the style and mode of delivery, the literature reviewed suggests that there are also significant issues with the content of sexual rehabilitation and sex education. Sexual rehabilitation seems to focus more on the physical elements of rehabilitation, but the emotional issues were not often addressed [29]. Information is also described as male-oriented, focusing on erectile dysfunction [22, 25, 29, 40, 48] rather than on issues that might be important to women with SCI. When issues specific to women are discussed they usually focus on fertility and reproduction rather than on sex, sexuality and relationships [47]. Two participants comment on the male-oriented nature of sex education for people with SCI:

When I was in rehab I was the only woman in that group, OK? There were 12 people there and I was the ONLY WOMAN, and all of the information they had was geared towards men. And I’m like, what’s wrong with these people? Don’t they know there are women in wheelchairs? (p. 88) [25]

What I found is, it is all centred around men, it’s all centred on their dysfunction and obviously they can’t get an erection… [p. 1090-1] [48]

The ‘right’ timing for the delivery of sex rehabilitation services or sex education [22, 24, 25, 29, 37, 40, 48] was also highlighted in the literature reviewed. Much discussion focused on whether early intervention was appropriate or not. However, our review indicates that the evidence on this was contradictory. For the majority of participants, introducing sex education in the early phases of rehabilitation was not seen as appropriate, but this was not the case for everyone. For example, one of the male participants in the study by New et al. [22] said that he ‘would like to have discussed [sexuality] a bit more at an earlier stage.’ (p. 5)

While early intervention was not seen as generally appropriate, some of the studies indicate that early signposting was beneficial to individuals with SCI even though they may not be ready to follow up on information and support in the early stages of recovery. In the study by Thrussell et al. [48] women ‘regretted missing opportunities to learn about what later seemed important’ (p. 1092). Participants favored an approach which offered information and support at different phases of recovery, while acknowledging that while some people would be receptive to this, and others not, that this was OK:

[…] So maybe just imparting more information to people and explaining how different it is […] some people would go, “Oh, I don’t want to talk about it,” and others would go, “No, actually, I really do want to talk about it.” “I need to know…” You need to be able to manage your expectations.” (p. 1092) [48]

The timing of sex education rehabilitation was identified as something that needs to be provided in the context of an individual’s life stage, prior sexual experiences and level of adjustment to injury [37]. A participant in Piatt’s study [40] also makes this point and offers the following advice to professionals offering sexual rehabilitation:

I guess like you go through recovering in different ways in different times. So I think in each of those different stages you have to figure out how to offer the conversation and offer the discussion on sexuality and intimacy and knowing that the way you offer it might vary on the stage you are in. (p. 30) [40]

In summary, the literature reviewed suggests that the quality of sexual rehabilitation and sex education for people with SCI is low. Professionals that deliver sex education are regarded as poorly equipped to carry out this work, often finding it embarrassing, or ignoring the subject altogether. When sex education and sexual rehabilitation does take place, it is often considered unhelpful and out-of-date, especially so for women. The evidence is contradictory on whether it is always appropriate to deliver sex education in the early phases of recovery from injury and many studies suggest that it is important to signpost to information about sex during all phases of rehabilitation.

Discussion

The review reported in this paper has analyzed 27 papers that focus on sex, sexuality and relationships for people with spinal cord injury, focusing specifically on qualitative accounts of their views and experiences. From the analysis, we identified four main themes: sexual identity; significant and generalized others, sexual embodiment; and; sexual rehabilitation and education. This body of literature developed out of critique of previous work, notably, as discussed in the introduction, its focus on quantitative, particularly medical focused research, a concern with physiology, sexual function and measurement and a predominant concern with men’s needs. Previous research had called for a focus on first-hand accounts of living with spinal cord injury, particularly to understand its impact on the very subjective experience of sex and relationships [8, 12]. This review took a broader, multifaceted understanding of sexuality, focusing on the social and subjective aspects of sexuality following spinal cord injury.

The analysis suggests a number of areas for research and practitioner developments. Firstly, that intimacy, sex and gender are all key aspects of sexual identity before and after a spinal cord injury. Whilst there has been a suggestion that women’s sexuality is not significantly affected by spinal cord injury, the experiences of women in the studies reviewed suggests that it is a central aspect of their identity post injury. Whilst a minority of individuals felt desexualized following their injury, overall the majority of studies reviewed suggest that sex, sexuality and regaining a sense of a ‘sexualized self’ were key to rehabilitation.

The review also highlighted negative experiences of individuals with a spinal cord injury and their interactions with practitioners concerning sexuality and sexual rehabilitation. Significantly the studies demonstrate general dissatisfaction with sexual rehabilitation, with reports that professionals ignore sex as part of rehabilitation or offered very poor-quality information and guidance. Individuals with a spinal cord injury expressed concern about the type of information they were offered which was often male-orientated and focused on physiological aspects of sex rather the person as a whole. There was a noted lack of training and knowledge about sex, particularly in its broadest sense encompassing physiology, psychology, identity and needs for intimacy. Improving education about sexual rehabilitation is considered by those with a spinal cord injury to be essential to improve quality of life.

The identity of women and men following injury takes place in cultural context, and gendered expectations are often implicated in individuals’ experiences and reactions by others to them. The review highlights that women’s sexuality following spinal cord injury remains under-researched. As discussed above, if education about sex is offered as part of rehabilitation the focus was typically on sexual performance, particularly on men’s sexual functioning, hence excluding women. The review noted an implicit assumption in the reported research that individuals were heterosexual and that their needs for intimacy and sex were best met within a heteronormative couple. Further research is needed to explore the needs and wishes of people with a spinal cord injury who do not identify with these norms, for example those who identify as LGBT +. Current education provision may serve to further stigmatize individuals with spinal cord injury if these norms are assumed in rehabilitation.

The potential for positive changes in relationships following spinal cord injury were noted in some studies. A narrative that compares ‘before and after’ injury was commonly noted in the review. Two potential narratives were articulated, one was of impairment and negative experiences. However, the second offered by people with a spinal cord injury was of the possibility for sexual discovery and rediscovery as part of a ‘new way of being normal’ [39]). Sakellariou [27] suggests that sociocultural barriers encountered by individuals with spinal cord injury, particularly in relation to sex and sexuality, are as disabling as the injury itself. They conclude that education provision has the potential to influence social attitudes and ‘make sexuality more accessible to disabled people’ (p. 101).

This systematic review has a number of limitations that should be acknowledged. Only papers published in either English or Spanish were included. We identified three papers that were published in other languages and we were not able to include these. Our particular search terms and delimiters may also have inadvertently excluded other materials that could have added to our analysis. In the review we focused specifically on papers that explored sex and intimacy and excluded papers that focused specifically on reproduction or reproductive health. In doing so we may be underreporting the significance and extent to which sex, identity and reproduction are interrelated both for women and for men.

References

Buyukavci, R., Akturk, S., Ersoy, Y.: Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with spinal cord injuries: two years’ experience at a tertiary rehabilitation center. Ann. Med. Res. 25(3), 365–367 (2018)

New, P.W., Guilcher, S.J.T., Jagal, S.B., Biering-Sorensen, F., Noonan, V.K., Ho, C.: Trends. Challenges and opportunities regarding research in non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 23(4), 313–323 (2017)

Kang, Y., Ding, H., Zhou, H., Wei, Z., Lui, L., Pan, D., Feng, S.: Epidemiology of worldwide spinal cord injury: a literature review. J. Neurorestoratol. 6, 1–9 (2018)

Morrison, B.F., White-Gittens, I., Smith, S., St John, S., Bent, R., Dixon, R.: Evaluation of sexual and fertility dysfunction in spinal cord-injured men in Jamaica. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 3, 17026 (2017)

Thompson, C., Mutch, S., Parent, S., Mac-Thiong, J.-M.: The changing demographics of traumatic spinal cord injury: an 11 year study of 831 patients. J. Spinal Cord Med. 38(2), 214–223 (2015)

Alexander, M.S., Mlynarczyk, A.C., Alexander, S.M., Aisen, M.L.: Sexual concerns after spinal cord injury: an update on management. NeuroRehabilitation 41, 343–357 (2017)

Pili, R., Gaviano, L., Petretto, D.R.: Ageing disability and spinal cord injury: some issues of analysis. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4017858

Singh, R.M.S., Sharma, S.C.: Sexuality and women with spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 23(1), 21–33 (2005)

Hocaloski, S., Elliott, S., Brotto, L.A., Breckon, E., McBride, K.: A mindfulness psychoeducational group intervention targeting sexual adjustment for women with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Sex. Disabil. 34(2), 183–198 (2016)

Barbonetti, A., Cavallo, F., Felanzi, G., Francavilla, S., Francavilla, F.: Erectile dysfunction is the main determinant of psychological distress in men with spinal cord injury: an update. Andrology 4, 13–26 (2016)

Anderson, K.D., Borisoff, J.F., Johnson, R.D., Stiens, S.A., Elliott, S.L.: The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord. 45, 328–337 (2007)

Rodger, S: Evaluating sexual function education for patients after a spinal cord injury. Brit. J. Nurs. 28(21), 1374–1378 (2019)

New, P.W., Seddon, M., Redpath, C., Currie, K.E., Warren, N.: Recommendations for spinal cord rehabilitation professionals regarding sexual education needs and preferences of people with spinal cord dysfunction: a mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 54, 1203–1209 (2016)

Rodger, S., Bench, S.: Education provision for patients following a spinal cord injury. Br. J. Nurs. (2019). https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2019.28.6.377

Walsh, D., Downe, S.: Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery 22, 108–119 (2006)

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3(2), 77–101 (2006)

Lincoln, Y.S., Guba, E.G.: Naturalistic Enquiry. Sage, Beverly Hills (1985)

Thomas, J., Harden, A.: Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Method. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Ray, C., West, J.: I. Social, sexual and personal implications of paraplegia. Paraplegia 22(2), 75–86 (1984)

Tepper, M.S., Whipple, B., Richards, E., Komisaruk, B.R.: Women with complete spinal cord injury: a phenomenological study of sexual experiences. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 27(5), 615–623 (2001)

Zhang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Chen, S.: Survey of reproduction needs and services: situation of persons with spinal cord injuries. Asia Pac. Disabil. Rehabil. J. 25(2), 21–34 (2014)

New, P.W., Seddon, M., Redpath, C., Currie, K.E., Warren, N.: Recommendations for spinal rehabilitation professionals regarding sexual education needs and preferences of people with spinal cord dysfunction: a mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 54(12), 1203–1209 (2016)

Kreuter, M., Taft, C., Siösteen, A., Biering-Sørensen, F.: Women’s sexual functioning and sex life after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 49(1), 154–160 (2011)

Leibowitz, R.Q.: Phenomenology of sexuality for women after spinal cord injury: emergent focuses on relationships. SCI Psychosoc. Process. 16(65), 70–76 (2003)

Leibowitz, R.Q.: Sexual rehabilitation services after spinal cord injury: what do women want? Sex. Disabil. 23(2), 81–107 (2005)

Sakellariou, D.: If not the disability, then what? Barriers to reclaiming sexuality following spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 24(2), 101–111 (2006)

Sakellariou, D.: Sexuality and disability: a discussion on care of the self. Sex. Disabil. 30(2), 187–197 (2012)

Maasoumi, R., Zarei, F., Razavi, S.H.E., Khoei, E.M.: How Iranian women with spinal cord injury understand sexuality. Trauma Mon. 22(3), e33116 (2016). https://doi.org/10.5812/traumamon.33116

McAlonan, S.: Improving sexual rehabilitation services: the patient’s perspective. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 50(10), 826–834 (1996)

Sunilkumar, M.M., Boston, P., Rajagopal, M.R.: Views and attitudes towards sexual functioning in men living with spinal cord injury in Kerala, South India. Indian J. Palliat. Care 21(1), 12–20 (2015)

Amjadi, M.A., Simbar, M., Hosseini, S.A., Zayeri, F.: The sexual health needs of women with spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Sex. Disabil. 35, 313–330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9495-7

Seddon, M., Warren, N., New, P.W.: ‘I don’t get a climax any more at all’: pleasure and non-traumatic spinal cord damage. Sexualities 21(3), 287–302 (2018)

Beckwith, A., Yau, M.K.S.: Sexual recovery: experiences of women with spinal injury reconstructing a positive sexual identity. Sex. Disabil. 31(4), 313–324 (2013)

Parker, M.G., Yau, M.K.: Sexuality, identity and women with spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 30(1), 15–27 (2012)

Giddens, A.: Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford University Press, Redwood City (2001)

Cramp, J., Courtois, F., Connolly, M., Cosby, J., Ditor, D.: The impact of urinary incontinence on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in women with spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 32(3), 397–412 (2014)

Fritz, H.A., Dillaway, H., Lysack, C.L.: ‘Don’t think paralysis takes away your womanhood’: sexual intimacy after spinal cord injury. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 69(2), 1–10 (2015)

Richards, E., Tepper, M., Whipple, B., Komisaruk, B.R.: Women with complete spinal cord injury: a phenomenological study of sexuality and relationship experiences. Sex. Disabil. 15(4), 271–283 (1997)

Tepper, M.S.: Lived eXperiences that Impede or Facilitate Sexual Pleasure and Orgasm in People with Spinal Cord Injury. Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania (2001)

Piatt, J.A., Knee, E., Eldridge, L., Herbenick, D.: Women with spinal cord injury and sexual health: the role of the recreational therapist. Am. J. Recreat. Ther. 17(3), 1539–4131 (2018)

Chapple, A., Prinjha, S., Salisbury, H.: How users of indwelling urinary catheters talk about sex and sexuality: a qualitative study. Brit. J. Gen. Pract. 64(623), E364–E371 (2014)

Westgren, N., Levi, R.: Sexuality after injury: interviews with women after traumatic spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 17(4), 309–319 (1999)

Basson, P.J., Walter, S., Stuart, A.D.: A phenomenological study into the experience of their sexuality by males with spinal cord injury. Health SA Gesondheid. 8(4), 3–11 (2003)

Li, C.M., Yau, M.K.: Sexual issues and concerns: tales of Chinese women with spinal cord impairments. Sex. Disabil. 24(1), 1–26 (2006)

Rohrer, J.R.: Factors in the marital adjustment of couples after the spinal cord injury of one of the partners. Ed.D. University of Cincinnati (2001)

Shakespeare, T.: ‘Help’ (Imagining Welfare). BASW, London (2000)

Grosz, E.: Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (1994)

Thrussell, H., Coggrave, M., Graham, A., Gall, A., Donald, M., Kulshrestha, R., Geddis, T.: Women’s experiences of sexuality after spinal cord injury: a UK perspective. Spinal Cord. 56, 1084–1094 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0188-6

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sarah Earle and Lindsay O’Dell contributed to study conception and design. Study identification, selection and data analysis performed by Sarah Earle and Lindsay O’Dell. Quality appraisal performed by Alison Davies and Andy Rixon. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sarah Earle with Lindsay O’Dell and all authors commented critically on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Earle, S., O’Dell, L., Davies, A. et al. Views and Experiences of Sex, Sexuality and Relationships Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. Sex Disabil 38, 567–595 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09653-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09653-0