Abstract

This article mobilises an analytical framework developed by the author in a series of solo and joint publications according to which religion has shifted from a Nation-State to a Global-Market regime, which it applies to the case of Eastern European Orthodox majority countries, including Russia, in modern times. Bringing together a large amount of research in a synthetic objective, it first examines how religion in Eastern Europe was nationalised and statised from the end of the eighteenth to the twentieth century. It looks at the particularities of the communist experience, and shows how it is best understood as a form of radicalisation of National-Statist trends. It then shows how neoliberal reforms have integrated these countries in wider global flows. The remainder of the article looks at different trends from the perspective of marketisation: the coextensive rise of Orthodoxy affiliation and nationalism, the qualitative changes within Orthodoxy, as well as the parallel developments of New Age derived spirituality and Pentecostalism, the two ideal-typical religious forms in the Global-Market regime, and by linking them to specific experiences of globalisation and social determinants. The conclusion argues that the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism as well as the religious trends that are developing today are the consequences of neoliberal reforms, the penetration of consumerism as a dominant ethos, and thus generalised marketisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

One of the most determining global events to have occured in the last decades has been the collapse of the Soviet Union and the communist bloc. This put an end to the Cold War and its ideological structure, and opened a new era in which market economics became hegemonic for global societies. In the immediate follow-up of this collapse, Orthodox-majority Eastern European (OMEE) countries shifted progressively yet markedly from state-planned to market economies, and processes of democratisation were initiated. One of the most striking developments parallel to the major economic and social reforms in post-communist countries has been the scope and nature of the religious revival. Overall, Orthodox-majority Eastern European countries (including Russia) have seen a spectacular rise in declared adhesion to Orthodoxy since the early 1990s, after half a century of state-enforced, more or less radical secularism and official state atheism.

Interestingly, sociological scholarship on religion in Eastern Europe has ignored the massive economic changes incurred since 1991 as both a focus and determinant, preferring to focus on political issues. Commentators have typically investigated these trends through the lens of secularisation, for instance as examples of the ‘re-publicisation of religion’ (Agadjanian, 2001) or of ‘de-secularisation’ Karpov (2010). In a recent edited volume, Greg Simons and David Westerlund typically refer to the background against which to understand religious transformations in post-communist countries as a shift to a ‘democratic era’ (Simons & Westerlund, 2015: 1) and the bulk of the contributions make no mention of the passage to capitalist economies, consumerism, and the consequences of neoliberal reforms. This is not to say that issues such as democracy are not important both descriptively and normatively, but the silence on the economic dimensions of the 1991 earthquake and its aftermath is highly problematic. Focused on political issues, social scientists have forgotten that the collapse of the Soviet Union and the communist bloc was not only due to political upheaval but also—and perhaps first and foremost—increasing technological belatedness and hardening economic difficulties. As Aurora Trif captures it: ‘The political and economic changes that have taken place since 1989 in Eastern Europe aimed at replacing the centrally planned economy with a market economy system’ (2008: 565) before anything else, including democracy.

In comparison, anthropologists (e.g. Köllner, 2012, 2013; Caldwell, 2005) have more readily remarked the coincidence of the shift to market economics and the religious revival, and used this in their analysis. Why is it then that sociologists have been blind to what is obvious for other disciplines?Footnote 1 The answer lies in my view in sociology’s enduring encroachment in the secularisation paradigm (Casanova, 1994; Gauthier, 2020; Tschannen, 1994) and its assumptions: social differentiation, methodological nationalism, a political and institutional bias, a focus on world religions and their ‘churched’ (Beyer, 2013) forms etc. Sociologists of religion have been trained without any real knowledge of political economy and of the history of economic ideas such as that of the market (Rosanvallon, 1979), and they wilfully contract economic issues out to economists (Gauthier, 2020).

Along with my colleagues Tuomas Martikainen and Linda Woodhead, we have been arguing that a major shift has occurred since the turn of the 1980s by which market economics have overturned the state as principal social regulator and contributed to profoundly reshape all social spheres since, including religion. As a consequence, we argue that religion today is best understood cast against the backdrop of this come-to-dominance of market economics under the guise of neoliberal reforms and the spread of consumerism as a desirable and structuring ethos (Gauthier et al., 2011, 2013a, b, c). In Religion, Modernity, Globalisation (Gauthier, 2020), I have expanded on this analytic and have suggested that religion (and every other social sphere) since the late nineteenth century has been shaped by two consecutive regimes: The Nation-State and the Global-Market one.

In this contribution, I bring together a large amount of quantitative and qualitative empirical research both sociological and anthropological in a synthetic objective. I propose an alternative interpretation to the secularisation paradigm-grounded one which remains dominant in the social sciences by mobilising the ‘Nation-State to Global-Market’ analytical framework on the case of Orthodox-majority Eastern European countries. In a nutshell, and contrary to the dominant social differentiation perspective, I consider that modern societies are, like their pre-modern counterparts, integrated wholes which, following Karl Polanyi’s suggestion in The Great Transformation (Polanyi, 1957), are embedded in a regulating sphere. Scholars agree that religion tended to play such a role in the pre-modern, traditional era, yet that such integration eroded at the hands of social differentiation. The core of my proposal is to consider that the particularity of modernity, in the wake of the Western Enlightenment, has been to shift these foundational and regulatory embedding functions first to the political sphere, via the Nation-State (both the idea and the institution itself), and more recently to the Market and its Global expansion. Because of Western dominance and its corollaries (colonialism, imperialism), these structures have been successfully disseminated worldwide, and locally appropriated, interpreted, translated, transformed as well as contested. Modernity can therefore be defined as the unification of the world through the political form of the Nation-State in the first place, and that of the Globalised Market in the second.

As a consequence, religion in the Nation-State regime was statised—differentiated, institutionalised, churched—and nationalised—made to serve the nation-building project—on the model of western European Westphalian Christianity, with an important emphasis on rationality, scripture and sober ritual for instance. Seen from this angle, formations of ‘the secular’ and secularisation are constitutive of the Nation-State regime, but are secondary with respect to the more encompassing processes of statisation and nationalisation.

The shift of the Nation-State to the Global-Market regime has been the result of a dual set of processes: The neoliberal and the consumer revolutions (Gauthier, 2020). The formidable rise of neoliberal ideologies, practices and policies at the turn of the 1980s successfully challenged the very nature, location and function of the state, eroding its soteriological and utopian investments, and changing its rapport to society. Neoliberalism can be defined as the extension of market economic principles to the entirety of the social, and the coextensive embedment of all social spheres within these logics. Consumption, meanwhile, has emerged as a massive cultural and social phenomenon, captured by the concept of ‘consumerism.’ Consumption is far more than the satisfaction of material needs and the exercise of utility, as liberal political economy would have it. It is one of the defining traits of today’s consumer societies, and consumerism shapes the values within consumer societies, as well as the rapports to the self, to others and to the world. It transforms identities into lifestyles, and shapes religion to cater to issues of ethics (how to live in the here and now) and personal identity. Consumerism also forcefully promotes what Charles Taylor has called the ‘ethics of authenticity and expressivity,’ according to which every individual ‘has his or her own way of realizing’ his or her own humanity, ‘and that it is important to live our one’s own’ (2003: 83) through the exercise of personal choice, in all spheres of life (Gauthier and Martikainen, 2013). As an integral part of economic and cultural globalisation, consumerism and the expressive individualism it carries erode the container function of the nation and opens onto an array of demands for recognition, as well as new, essentially reactionary, conservative and ethnic investments of the ‘nation.’

In a sense, neoliberalism affects religion from ‘above,’ as it changes the conditions for the state’s regulation, and introduces a less vertical hierarchy between societal institutions, opening the door to a more public role for religion (Martikainen and Gauthier, 2013). It also pressures institutions to conceive of themselves as enterprises and to adopt management and marketing practices emanated from the business world. Consumerism, on the other hand, contributes to shape religion ‘from below,’ through the lifestylisation of cultural and social practices and the ethics of authenticity (Gauthier, 2021a, 2021b; Gauthier and Martikainen, 2013). Overall, I argue that the marketisation of religion leads to a partial de-differentiation of religion, which blends into new hybrid forms with tourism, entertainment, consumption, arts, politics and so on. It similarly conduces to the blurring of the private/public as well as religion/secular divides on which the sociology of religion has rested its analyses. The combined effects of neoliberalism and consumerism have been massive over the last decades on all dimensions of societies, including education, health care, law, politics, culture, and religion, as ‘the Market’ was instituted as the embedding logic, effected through the dismantling of the societal arrangements of the Welfare, communist and post-colonial states.

In the case of OMEE countries, the shift from the Nation-State to the Global-Market regime occurred over a very short period of time, although such processes are gradual and non-linear. At the same time, this region is often portrayed as being characterised by economic under-development, marginality with respect to global flows, revived nationalism blended with an ‘illiberal’ contestation of Western European values, and a massive conservative, reactionary, and authoritarian turn. From this perspective, the Orthodox revival questions processes of secularisation, but it also appears linked to a deficit of integration within global flows and a strong reaffirmation of that which the marketisation thesis I am defending (i.e. the embedment within the Global-Market regime) says belongs to an era which we are supposed to be leaving: a strong state and the reaffirmation of nationalism. A closer look, though, reveals a different picture.

This article first examines how religion in Eastern Europe was nationalised and statised from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. It looks at the particularities of the communist experience, and shows how it is best understood as a form of radicalisation of these trends. The article then shows how neoliberal reforms as of the 1990s have integrated these countries in the wider global flows. The remainder of the article looks at different trends from the perspective of marketisation: the coextensive rise of Orthodoxy affiliation and nationalism, the qualitative changes within Orthodoxy, as well as the parallel penetration of New Age tropes and Pentecostal boom, the two ideal-typical religious forms in the Global-Market regime. The conclusion argues that the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism as well as the religious trends that are developing today must be correlated to the combined effects of neoliberal reforms and generalised marketisation.

On a more general note, the ‘Nation-State to Global-Market’ framework is designed to shed new light on the transformations of religion over the last century on a global scale. It is an answer to the calls to ‘provincialize’ the West (cf. Chakrabarty, 2008) and de-centre sociological analysis by widening the scope, while at the same time recognizing the profound and long-lasting effects of modern Western ideals (namely the State and the MarketFootnote 2) on societies and cultures worldwide. This lens has been applied until now to the cases of Indonesia and global Islam, as well as to transversal and transnational trends affecting religion. The cases of Eastern Europe, China, global New Age, and African Pentecostalism will be examined in a forthcoming volume. The framework was also greatly enriched by the making of the Routledge International Handbook on Religion in Global Society (Cornelio et al., 2021). Here I concentrate on Orthodox-majority Eastern European countries for practical reasons, but I suggest that my argument could be expanded to include, with some nuances and contextualisation, to other Orthodox-majority countries like Cyprus and Greece, and to other non-Orthodox Central and Eastern European countries. In order to do so, I summon works from economics, political science, history, and the wider social sciences. In an age where academia is involved in a process of ever-specialization, I oppose an intentionally interdisciplinary and generalist outlook which renews with the aims of classic sociology and can help open new avenues for research in a time of profound yet misrepresented changes.

The Nationalisation and Statisation of religion in Eastern Europe

Nation-state-building in Central and Eastern EuropeFootnote 3 has been intimately tied to the destinies of religion, and even more so in Orthodox countries. While Western European nation-states emerged as legacies of the Westphalian system, Central and Eastern European countries were carved out of disintegrating Empires (Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian) (Krastev, 2016). In what was to become Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania, the Ottoman empire recognised Orthodox Churches as part of the Sultan’s ‘protected communities’ (millet). These evolved into proto-national structures which served as frameworks for the development of modern nationalism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Eastern Christianity was culturally diverse and fragmented from its inception, and the grounds for the grand Schism of 1054 between Constantinople and Rome had to do with their conceptions of ecclesial authority: conciliar and decentralised for the former, monarchic and centralised for the latter. The establishment of the Moscow Patriarchate in 1589 was another step in the expansion and diffraction of Eastern Orthodoxy through processes of ‘vernacularization’ and ‘indigenization’ (Roudometof, 2014: 162) by which Orthodoxy became bound to specific languages and cultures before being absorbed into ‘ethnic identities’ (ibid.) that formed the basis for modern nation-state construction.

The influence of Western European modernity and the Westphalian model (one political rule, territorial sovereignty, and one religion) on Eastern Europe became increasingly important in the nineteenth century. Similarly, the emergence of the idea of nationalism ‘as the world’s main legitimizing force’ over the course of the nineteenth century ‘altered the social bases of societies around the globe’ (Roudometof, 2014: 164) and had a tremendous impact in Eastern Europe. The disaggregation of the Ottoman Empire over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth century contributed to the formation of new territorially sovereign nation-states, which in turn ‘led to the construction of independent, autocephalous national Churches’ (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 11). In a word, ecclesiastical and political frontiers were made to overlap, as Orthodoxy became nationalised across Eastern Europe (while remaining imperial in Russia) (Roudometof, 2014: 164–5). In the Russian Empire, modernisation mainly meant the increase of the control of the state over a sovereign territory, and was thus enforced from above. This had the effect of bringing the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) evermore under the direct control of the state.

In places such as Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania, ‘the religious markers of the earlier centuries were reconfigured to relate to each local nation […] Out of this geographical reterritorialization and the concomitant relativization of religious identity came the modern synthesis between church and nation.’ (Roudometof, 2014: 165) The nationalisation process provided the grounds for claims over canonical territory. In other words, autocephaly was not the result of ecclesiastical concerns as much as a means to provide the ‘material and ideological infrastructure for the nationalization of the masses.’ (p.87) A country like Ukraine, which Yelensky describes as ‘a retarded suburb of Russia and Poland’ (2006: 151) had to choose between becoming a part of a greater Russian nation, or building a nation-state of its own. In all cases, then, the choice was between a nation-state and a nation-state. The tensions within Ukraine resulted in a fractured religious landscape that mirrored—and continues to mirror—national and political divides: on one side, the ambitions of the Kiev ‘Patriarchate,’ on the other, the submission to that of the Moscow Patriarchate. Everywhere, ‘the Church had to engage with the newfound forces of nationalism and develop a narrative of legitimization or resacralization that would be meaningful in a cultural universe in which people were increasingly thinking of themselves as belonging to a nation.’ (Roudometof, 2013: 86) Nation-state formation in Eastern Europe happened over a much shorter time than in Western Europe, and building a rapport between the nation and the Church proved to be the most efficient and shortest route (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 11). In Bulgaria as elsewhere, nationalism and ecclesiastical independence ran together. The only difference is that, in Bulgaria, Church autonomy was granted by the Sultan (1870) before it became a state (1878), while things happened in the reverse order in other South-Eastern European countries.

The modern transformation of Orthodoxy within the Nation-State regime was both cultural (the link between Church and nation) and structural (institutionalisation of autocephalous national churches). Churches and states emerged in parallel, and this contributed to shape the former’s religious mission. In other words, modern Orthodox Christianity is to a large extent the product of modern processes of nationalisation and statisation (Roudometof, 2019). Although by no means linear and uncontested, the redeployment of religious and national identities was ‘ultimately extremely successful’ (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 11). Its novelty was downplayed by renewing the principle of symphonia (complementarity) of the political and religious leadership, which characterised the Byzantine era: ‘According to Church tradition, the religious establishment complements the secular leader in his execution of duties, providing spiritual leadership and exercising moral control upon state authority. On the other hand, secular leadership is often allowed and expected to play a role in protecting, expanding, and serving the religious institution.’ (ibid.) Symphonia has always been at the crux of Orthodoxy’s enculturation and adaptation to circumstances, even if its signification has changed (cf. Makridès, 2006).

In Western Europe, the ‘modern cultural and political programme’ (Eisenstadt, 2000) was enacted in tension with the Church—less so in Protestant lands, and in outright conflict in Catholic ones like France. In Eastern Europe, the Orthodox Church was a main actor in the nation-building process, and modernisation did not involve ‘secularisation’ per se, at least not until communist rule.

The communist experience: Radicalized Statisation

It is important to note that the nation and state-building process was not achieved in most parts of Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War. State boundaries had in many cases fluctuated and were contested, hindering claims of territorial sovereignty. Following the Yalta accords of 1945, Eastern Europe was entirely ‘reorganized in a manner that enabled communist control of individual states’ (Leustean, 2009a: 1). This involved the creation of inner ‘Republics’ in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia that were only autonomous in principle. The constitutive ambivalence of the symphonia principle was once again summoned in the context of the Cold War (1945–1991), when Orthodox Churches had to survive in authoritarian/totalitarian atheist political regimes.

The communist experience is often portrayed as having frozen, even ‘deep-frozen’ religious developments. A closer look reveals more complex rapports. The difficulties in simply eliminating religion were brought to light by the intense interwar Soviet persecution of the ROC and other religions, including indigenous Siberian Shamanism. While only an estimated few hundred parishes had survived the repression at the end of the 1930s, it proved more difficult to un-root popular devotion. As of 1943, Stalin initiated a new strategy by which the Church was made to serve the Soviet state and the ‘political expansion of communism to neighbouring countries’ (Leustean, 2009a: 3), and even beyond the Iron Curtain. Outside the Soviet Union, ‘aggressive anti-religious policies’ were unanimously enforced at first, before evolving into different patterns. In Romania, for example, mass purges decimated the Church hierarchy, more than half of the monasteries were closed, 2000 monks were forced to secularise, and lay activists were imprisoned (Hämmerli, 2018: 38). In Albania, Bulgaria, and Serbia, the Orthodox church faced continued repression, yet the latter was slackened in Armenia and Romania in exchange for support of the regime (Leustean, 2009b). The situation in each country remained relatively stable throughout the communist era, with Churches remaining carefully distanced from contestation until the end of the 1980s. Submission and even collaboration (Church hierarchies were tightly controlled by the state) with the regime enabled the Churches to survive. Church authorities tried to convince themselves and others that ‘collaboration with the state could not alter the Church but only have hic et nunc effects.’ (Leustean, 2009a: 3).

The consequences of five decades or more of state-enforced atheism in terms of secularisation is a debated question. Surveys conducted in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union reported that 37% of the population in Russia, 39% in Ukraine, and 59% in Bulgaria ‘describe themselves as Orthodox Christians’ (Pew Research Center, 2017). Qualitative appreciations are difficult, yet characteristics include ‘the forceful separation of religious life from the larger society’ (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 12, emphasis in text), the formatting of religion into well-discernible and controllable institutions, as well as its privatisation and spiritualisation (Köllner, 2013). Depending on the country, Orthodoxy was either politicised (in favour of the regime, never in opposition as Catholicism in Poland), i.e. made to serve the communist (Soviet Union) or national-communist (Romania) regime, or de-politicised. Orthodoxy was subordinated to the political religion (Gentile, 2005) constructed by these regimes. Arguably, the most severe repression was conducted in states that had elaborated the most explicit and elaborate political religions of their own, as in the Soviet Union.

Overall, religion was controlled and formatted by the state (i.e. statised) in order to be controlled, or wiped out. Somewhat paradoxically, one ‘major Soviet legacy was the nationalization of religion. Structured as a multi-ethnic and multinational empire, the Soviet Union was a crucible of strong ethnic and national identities (in spite of the rhetoric or internationalism that failed to produce a durable meta-ethnic “Soviet nationality”).’ (Agadjanian, 2015: 246). OMEE countries therefore illustrate a particular modulation of the Nation-State regime. From the nineteenth century to the communist era, there is a lot of continuity when one considers how religion was progressively framed by the state and the nation. The conclusion that follows is that the communist era acted to reinforce Nation-State regime characteristics and the submission to the rule of the state to an extreme degree (with interesting parallels in China for instance).

The breakup of the Soviet Union returned communist territories to their pre-Soviet national or proto-national constituencies. In the case of Moldavia, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Central Asian Republics, the administrative cut-out of the Soviet Union provided the grounds for post-Soviet nation-building. Orthodox Churches had been effectively institutionalised within the boundaries of these inner Republics, in more or less subservience to the Moscow Patriarchate, the latter of which espoused the imperial pretensions of the Soviets as it had the Tsars’. Outside the Soviet Union, the communist rule involved Orthodoxy’s nationalisation, although to less of an extent than in Romania. Incidentally, while the statisation of religion in Eastern Europe was quite straightforward and explicit, its nationalisation was a complex and unfinished process.

Gorbatchev’s Perestroika started to relax the states’ grip on religion (Köllner, 2012: 3). Yet it is the collapse of communism that obviously had the most impact on the whole region. Politically, the consequences were the fragmentation of the three multi-ethnic or multi-national states into a myriad of independent states, either violently (Yugoslavia especially but also in many places within the ex-Soviet Union) or peacefully (Czechoslovakia or the Baltic States, Rimestad, 2012). Local societies were destabilised to an unimaginable extent and or the Baltic states, socioeconomic conditions were rattled with more or less rapidity, putting enormous stress on the social fabric. In this context, the Church emerged as a rare provider of continuity with a sharply disrupted past. Similarly, the Church renewed with its pre-communist function of accompanying nation-state-building processes and delivering much-needed legitimacy for the new independent states. The ‘springtime of nations’ was therefore accompanied by claims of ecclesiastical autocephaly, which also created its load of disputes.

Varieties of eastern European neoliberalism

Once the socialist system in Eastern Europe collapsed, every country, newly formed or not, embarked on a pathway that meant to turn them into full-fledged market societies. By the turn of the 1990s, neoliberalism was well installed as the unchallenged hegemonic economic ideology, and neoliberal reform strategies were the only ones available. Eastern European developments were patterned rather than random, yet the overall picture is one of ‘diversity within neoliberalism’ (Bohle & Greskovits, 2012: 4–5, emphasis in text). Beyond the purely economic and material shock, data shows a massive social anomie in the wake of the unexpected communist breakdown: decrease in life expectancy and fertility, as well as dramatic increases in the rates of infant mortality, addiction, crime, inequalities, long-term unemployment, and risk of poverty. All of these indicators have remained high since, without any clear correlation with respect to the type of neoliberal pathway (Bohle & Greskovits, 2012: 50).

Neoliberalism ‘claims the superiority of markets and competition over state-governed mechanisms of social and economic organization’ (Bohle & Greskovits, 2012: 57), and is translated into policies such as market creation and deregulation, state downsizing, limited welfare provision, the promotion of competition in every field, and privatisation. From the immediate aftermath of the collapse, Western advisers and supranational institutions such as the IMF sustained a preference for ‘rapid and comprehensive marketization over any other transformation strategy.’ (ibid.) These pressures were met by local political actors, who often had little or no training in market economics and therefore tended to embrace the works of Milton Friedman and the neoliberal agenda as the obvious antidote to excessive socialist statism (Ban, 2016; Bohle & Greskovits, 2012; Ringvee, 2013; Trif, 2008). On all sides, the neoliberal agenda was presented as ‘the only way to transition to a capitalist society’ (Bohle & Greskovits, 2012: 61). The European Union only became heavily involved in the last half of the 1990s, yet also promoted neoliberal reforms as part of the road to an eventual inclusion in its free market zone and political union. According to analysts, the very enlargement of the EU to Eastern European countries was a neoliberal project that aimed to open new markets and cheap labour possibilities for core countries (Bohle & Greskovits, 2012; Trif, 2008, 2014; Ban, 2016). This program involved the institutionalisation of regulatory norms and processes that took away some of the state’s sovereignty and regulative powers, enacting the anti-political and anti-democratic effects of neoliberalism described by many scholars (e.g. Gauthier, 2020; Harvey, 2005; Saad-Filho & Johnston, 2005).

Using a Polanyian approach, Bohle and Greskovits (2012) distinguish between the more radical, ‘disembedded’ neoliberalism of the Baltic countries and the more moderate, ‘embedded’ neoliberalism of the Visegrad countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and later Croatia). Countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, as well as some post-Soviet republics, embarked belatedly upon the paths of radical reform, yet caught up with the Baltic states on the disembedded neoliberal path by the mid to late-2000s. Bohle and Greskovits do not extend their analysis to Ukraine, Russia, and other Orthodox majority post-Soviet states (Georgia, Armenia, Moldova, Belarus etc.), but neoliberal reforms have similarly impacted the entire region. Overall, the socio-economic history of post-Soviet OMEE can be divided into two or three phases: a first period of instability of up to a decade, followed by years of pro-active neoliberal reforms, and a contemporary phase of EU-integration, consolidation, or aspiration. Bohle and Greskovits propose a classification based on how much national economies have shifted towards finance and services, and how much they rely on skilled labour as well as entrepreneurial, management, and marketing classes. They classify Visegrad countries within the semi-core of international flows, while countries like Bulgaria and Romania, which are developing these socioeconomic classes but whose economies are still geared on industry and primary resources, are classified as semi-peripheral. The ex-Soviet republics, as well as Russia itself (notwithstanding large agglomerations), are relegated to a peripheral status.

This typology must not deter from the basic fact that all Eastern European countries have become integrated into the global economy, albeit to different extents. By 2011, the neoliberal-oriented Fraser institute ranked the bulk of Eastern European countries above the global mean as regards ‘economic freedom,’ while private-sector output stood at around 70% of GDP (Shleiter & Treisman, 2014: 95). Meanwhile, national economies increasingly shifted from heavy industry to services, and international trade in the region rose faster than anywhere else in the world between 1990 and 2012. In other words, ex-communist economies reoriented themselves towards ‘foreign markets in Europe and elsewhere’ (Shleiter & Treisman, 2014: 96). According to Shleiter and Treisman: ‘In short, the countries have transformed their militarized, over-industrialized, and state-dominated economies into economies based on private ownership and integrated into global commercial networks’ (ibid.), thereby catching up with countries of similar income levels. The authors note how household consumption has drastically increased (88% on average, versus 56% elsewhere in the world), with overall economic growth levels over this period exceeding the global mean, after an initial contraction in the immediate aftermath of the communist collapse. In the Visegrad countries and Russia, household consumption rose significantly higher than the average global rate, and car ownership rose from 10 to 25%. In terms of information technology, Eastern Europe ‘has surged ahead, evolving from a backwater to an overachiever. By 2013, the region’s cell-phone subscriptions per person, at 1.24, had overtaken the rate in the West’ (Shleiter & Treisman, 2014: 96–7), while Internet use (54%) only fell behind that of North America and Western Europe. This picture prompts Shleifer and Treisman to celebrate that ‘postcommunist states have become normal [sic!] countries—and in some ways, better than normal.’ (Shleiter & Treisman, 2014: 97).

This celebratory alignment of statistics can be balanced out for more objectivity. The case of Romania serves as a case in point. While Visegrad countries ‘managed to adopt a faster pace of economic and social transformations and achieved a better insertion in the global market economy by developing complex industries and coherent political strategies that led to macro-economic stability’ (Gog, Forthcoming), Romania made a belated start and mainly achieved to become a ‘dependent capitalist economy that generated specific post-socialist institutional mechanisms in order to allow for a rapid integration into the world market economy.’ (Gog, Forthcoming; for a complete analysis, see Ban, 2016). This transition was accompanied by ‘the forced implementation of asymmetrical policies that eroded the welfare state and social protection mechanisms and created an economic environment that was favourable to foreign investments.’ (Gog, Forthcoming) The EU and IMF-imposed deregulation of the labour market (in order to access loans to absorb the 2008 financial crisis) dramatically restricted the power of unions and produced flexibility, instability, and insecurity as protective measures shrank. All of this has acted as a ‘structural pressure on workers to adapt to a new precarious and competitive environment.’ (Gog, Forthcoming).

All of this indicates three things: First, that neoliberalism has been the major if not the only source of inspiration for the reform of these post-communist countries’ infrastructures and economies. Second, these reforms have deeply impacted the culture and social fabric of these countries, which are now partially if not fully integrated within global flows with more or less developed service industries. Third, the post-communist era has led to a profound penetration of consumerism in virtually all classes of society, whether as a lived reality or a frustrated aspiration. Consumption rates, the penetration of information technologies, in addition to the shift from industry to service economies, mark an important change in the cultural and social ethos of these countries. All of this has had decisive impacts on the religious landscape.

The return to orthodoxy and the rise of nationalism

The most striking feature of the post-communist period has been the sudden and massive rise in declared adhesion to the Church, and even more so in Eastern Christianity majority countries. The numbers are striking. According namely to a 2017 Pew Research report (2017: 5), identification with Orthodoxy is as high as 93% in Georgia, 92% in Moldova, 88% in Serbia, 86% in Romania (which also has a share of 5% of Hungarian speaking Catholics), 78% in Ukraine (which also counts 10% of Catholics), and 75% in Bulgaria (which counts 15% of Muslims) [see Fig. 1]. All of these countries count only negligible numbers of ‘unaffiliated’ cohorts. In a country like Belarus which counts a relatively high number (11%) of unaffiliated, 73% identify as Orthodox against 12% of Catholics. In Russia, 71% identify with Orthodoxy against 15% of unaffiliated and 10% of Muslims. For the value of comparison, Poland records 87% of adherence to Catholicism, Croatia 84%, and Hungary 56% against 21% of unaffiliated and 22% of ‘other’ religions. At the other end of the spectrum, the Czech Republic aligns on Western European standards with 72% of unaffiliated and 21% of declared Catholics. These high numbers are only rivalled by rates of ‘belief in God,’ which score 95% in Moldova and Romania, between 75% and 87% in Russia, Bulgaria, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, and Serbia, while the rate is 59% in Hungary and only 29% in the Czech Republic. Overall, adherence numbers rose exponentially after the fall of communism before stabilising in the years 2000s and dropping slightly since 2010.

Religious landscape of Central and Eastern Europe (courtesy Pew research, 2017)

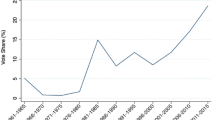

This return to Orthodoxy has converged with the rise of nationalism. The Pew report shows ‘strong association between religion and national identity,’ as Orthodoxy is widely perceived to be an important part of national identities. Overall, strong nationalism is positively correlated with high religious identification [see Fig. 2]. Importantly, though, adherence does not translate into weekly church attendance: Romania scores the highest in this regard with 21% of declared Orthodox attending service regularly, with Moldova trailing at 13%, Belarus and Ukraine at 12%, Russia and Serbia at 6%, and Bulgaria at 5%. In comparison, 45% of Catholic Poles attend church weekly, compared with 12% of Hungarian Catholics. Similarly, daily prayer is relatively low, ranking between 15 and 48%, well below the US rate of 55%. The data therefore supports the argument that the ‘return to Orthodoxy’ is first and foremost linked to the post-communist investment of the nation as an identity, with Orthodoxy acting as a central part of that identity. It is not, on the other hand, correlated with a massive hike in regular church attendance, which has remained low after an initial rise following 1991 [see Fig. 3].

Association between Orthodoxy and national identity (courtesy: Pew research, 2017)

Weekly church practice levels across Eastern European countries (courtesy: Pew research, 2017)

Overall, then, the impressive number of adherents to Orthodox Christianity speaks of the strength of a form of cultural rapport to religion rather than experienced religiosity and firm commitment to Orthodox practices. These figures therefore hide at least as much as they show, and require further investigation.

Yet for the time being, when we cross these statistics with the variegated neoliberal pathways of the post-Soviet era, what stands out is a general negative correlation between declared religious affiliation and the degree of integration within global flows and the success of the shift towards a consumer society. With respect to Bohle and Greskovits’ typology, peripheral countries tend to have higher affiliation rates to Orthodoxy, while semi-core and semi-peripheral countries tend to have lower ones. This is one way of explaining the difference between the very high statistics in beliefs and belonging in OMEE countries compared to Catholic-majority Central European ones. In this respect, the very high level of religiously unaffiliated in the Czech Republic (72%, versus 21% Catholics and 6% ‘other’) can be understood as being linked to the historically high level of cultural and economic integration of that country with Western Europe. This stands in stark contrast with the very high levels of Orthodox identification in peripheral countries such as Moldova, Armenia, and Belarus. Religion in general and Orthodoxy in particular have certainly acted as refuges in the face of radical changes, yet the picture is not complete without interrogating the specificities of nation and state-building under neoliberal conditions.

For Agadjanian, the ‘emergence of religiously informed nationalisms […] was a logical effect’ (2015: 246) of the nationalisation of religion under communism. Considering the history of the region and the unfinished process of nationalisation as well as the capital role of the Orthodox Church in the nation-building process, it is not surprising that people renewed with the Church, which could provide a sense of continuity and community after such a brutal rupture. Through its valuation of ‘Tradition’ and beyond its orientation to the past, Orthodoxy could provide building blocks with which to resume the pre-communist nation-building processes that accompanied neoliberal state reforms. Agadjanian and Roudometof compare the Eastern European case with that of Third World countries, where religion has been key in ‘maintaining and revitalizing an identity narrative in the face of globality.’ (2005: 13) They write: ‘In the post-1989 period, the particular vision of Eastern Orthodoxy as a conservative social force, which inhibited liberal modernization, was revived, setting off a clash between the traditional communitarianism of the Orthodox Church and the neo-liberal developmental strategies that prioritize individual rights, privacy, democratization, and unimpeded transnational processes.’ (2005: 12) Flora and Szilagyi make a similar point when they argue, in the case of Romania, that ‘after the collapse of the communist dictatorship, religion appeared to many as the only legitimate institutional and spiritual means available to fill the post-1989 ideological vacuum. After their prolonged period of marginalization, churches and religious organizations had to suddenly adapt to unexpectedly high social demands. Religious institutions had to define or redefine their social meaning to effectively address the changing set of contemporary social expectations.’ (Flora & Szilagyi, 2006: 109) With the exception that globalization, consumerism, and the Market were certainly among the ideologies available along with religion in the aftermath of the communist collapse, these authors do make a good argument, and one that can readily be generalised. In the midst of shaken political institutions—or even the privation of such institutions, as in some of the post-Soviet republics—, the Orthodox Church was perhaps the ‘sole remaining force for institutional nation-building.’ (Yelensky, 2006: 149) According to Yelensky: ‘The age of globalization reinforces the Church’s role as the historic repository of nationhood, national values, and cultural identities.’ (ibid.)

The Eastern European case shows how globalisation does ‘not abolish nations as relevant imagined communities’ (Yelensky, 2006: 165) as much as it changes the meaning of the nation (and nationalism), as well as the dynamics in which it partakes. Already in 1992, Eric Hobsbawm diagnosed the trends that are still unravelling as a consequence of the fall of communism. He wrote that the new rise of nationalism in Central and Eastern European countries paradoxically signalled ‘the decline of nationalism,’ (Hobsbawm, 1992: 163) at least in the form of the ‘old Wilsonian-Leninist ideology and programme.’ (p.187) His analysis rings true in retrospect, as post-Soviet nation-building does introduce significant ‘new elements in the history of nationalism.’ (p.183, emphasis added) Hobsbawm was quick to note that while nationalism has been the beneficiary of the communist collapse, it was not among its causes, except in the case of some Soviet republics such as Armenia. Contemporary nationalism in OMEE countries, therefore, is an essentially reactive movement in the face of unprecedented transformations. It is no longer ‘the historical force’ (p.169) that once drove political modernity. Nationalism today is not a positive, progressist, propositional, and holistic political programme ‘as it may be said to have been in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.’ (p.191) Similarly, the nation-states of a century ago tended to be large, multi-ethnic, multi-national, and linguistically heterogeneous, while today’s nationalism is fragmenting and ethnic (‘nation-splitting’ rather than ‘nation-building’). Hobsbawm cites Miroslav Hroch, for whom post-communist nationalism and ethnicity are ‘a substitute for factors of integration in a disintegrating society. When society fails, the nation appears as the ultimate guarantee.’ (p. 173) The same could be said about religion, and it is no coincidence then that both it and the nation have combined in the ways they have in the aftermath of 1989–1991.

Another salient element in this analysis is how late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century nationalism, including later post-colonial nationalism, was internationalist, in the sense that nations were constituted as putative equals in a world-society of container-nations. The nationalism that emerged in the 1990s, on the contrary, stood (and continues to stand) for political order and territorial integrity of sovereign states against the idea of the global, with its perpetual change and its unpredictable ebbs and flows. The revival of nationalism is therefore a protective gesture that expresses the fragility of nation-states in this new global environment as well as a nostalgia for its container function and the days when the nation-state had a firm grasp on things (or at least seemed to) and was invested with utopian and soteriological functions. The nation, then, and religion with it, are invested quite differently in today’s nationalist movements than a century ago. While Orthodoxy and nation-building went hand in hand in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the communist experience cast religion in radically secularist terms, as a remnant of the past and the recluse of superstition. Today, nationalism and religion appear as essentialist elements rooted in a past that is summoned against the tides of globalisation (Gradvohl, 2018; Genté, 2018; Grabbe and Lehne, 2018; Zawadzki, 2018; Ignatieff, 2014).

Significantly, the conservative religious revival concerns roughly the same demographics as the populist base, i.e. social classes that have not particularly benefited from globalisation, such as peasants, low-skilled industry workers, and rural areas. In this respect, the de-politicising effect of neoliberalisation processes is a primary factor in the rise of reactive nationalism.Footnote 4 Hobsbawm already noted how supranational market-enforcing institutions such as the IMF and, later, the WTO, as well as a score of other economically-minded institutions, eroded state sovereignty and marginalised national issues. Indeed, a major function of the earlier nation-state was to constitute ‘a territorially-bounded “national economy” which formed a block in the larger “world economy”.’ (Hobsbawm, 1990: 181) Today, the dynamic is reversed: it is the impersonal imperatives of the global economy that determine to a large extent the health and shape of national economies. Contemporary nationalism arises in the wake of the loss of control of the nation-state (Sassen, 1995) over the destinies of its people in economic and non-economic matters, and as economic determinants override societal institutions. Neoliberalism, in other words, has been a major factor counting for the concomitant rise of both nationalism and Orthodox affiliation.

Behind the stats: Changing orthodoxies

The coupling of religious conservatism and nationalism is far from being the only change to have happened in OMEE countries. Indeed, many changes are occurring under the surface of statistics and the gloss of official discourse. An example is the Russian Orthodox Church, which has tried to adapt to its new social and political legitimacy as well as to the new pluralist situation and ‘structural secularism’ (Agadjanian & Rousselet, 2016: 30) of the post-Soviet era. The ROC has adopted a Manichean worldview that conveniently opposes ‘secular (neo)liberalism’ (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 6) to the solidity of Tradition. The Church severely criticises the ‘anthropocentric universe’ which underlies the ‘neoliberal worldview,’ as well as its emphasis on the absolute liberty of the individual as a supreme value, and warns against the perils of a ‘new totalitarianism’ that menaces to dissolve communal bonds and undermine the very notion of “sin”.’ (ibid.) This response aligns itself on other conservative and even fundamentalist ones in the world, which points to a global process of ‘standardization and unification of religious phenomena (as of other cultural forms).’ (ibid.) At the same time, and somewhat paradoxically: ‘these forms of homogenization are accompanied and counterweighed by an emphasis on specific identities, by the worship, fashion, and even positive evaluation of “difference” for its own sake. The revival of ostensibly traditionalist religious particularisms around the world is part of a broader reaction that involves the reassertion of local, religious, [and/] or ethno-national identities. In spite of their self-proclaimed traditionalism and anti-globalist, protective rhetoric, these movements do—objectively—legitimize themselves through the globalized Western discourse of multiculturalism and the universal acceptance of individual and/or collective rights.’ (ibid.) In sum, then, ‘they position themselves precisely in opposition—but by this very fact they inscribe themselves into the new global taxonomy as its legitimate part (or party), as its counter fort.’ (ibid.) In other words, traditionalists have moulded themselves into a negative mirror-image of full-fledged marketised religious forms more than they have successfully prolonged the characteristics of the Nation-State regime in a global world: ‘the authoritative and dominant discourse of the Church, in spite of all critique, is a discourse of negotiation rather than a discourse of confrontation with the liberal, secular world. Globalization is directly acknowledged as an “inevitable and natural process” bringing many positive results’ (Agadjanian and Rousselet 2006: 48, quoting from the Proceedings of the Jubilee Bishops Council of the Russian Orthodox Church 2000)—perhaps above all economic. Indeed, the ROC’s critique is less aimed at liberal economics than liberal secularism.

Since the fall of communism, the state’s control on religion has loosened significantly. At the same time, state funding was revived and has tended to grow ever since. In most cases, Churches have enjoyed a positive reputation, only rivalled by the army. Yet the post-communist situation is one in which pluralism now shapes things in theory as well as in practice, as states introduced clauses of freedom of religion and recognition of a multiplicity of religious institutions in the new post-communist constitutions. This has been a major challenge for many Orthodox Churches, whose tradition of hegemony and association with the nation make it difficult to conceive of themselves as ‘competitors’ in a plural landscape of ‘religious options.’

For Sorin Gog, the ‘atheisation process’ under communist rule was a failure, since in most cases religiosity simply receded within the private sphere, only to invade the public after 1991 (Gog, 2011: 93). The region therefore shares the same pattern of privatisation/de-privatisation that has been observed elsewhere (Casanova, 1994). Similarly, the rollback of the absolutist state under neoliberal guidance has opened the way for the de-differentiation of religion and its overtaking of ‘certain social functions that the state was not ready to fulfil’ (ibid.), namely in the provision of healthcare, education, care for the elderly and so on, in a way reminiscent of the US Faith-Based Initiatives (FBIs), which is a classic case of the impact of neoliberalism on religion (Martikainen & Gauthier, 2013). In a country like Romania, Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and Orthodox Churches have operated a division of labour in the field of welfare, and these provisions have become intrinsic to their evangelisation (‘growth’), positioning, and communication strategies.

Eastern European Orthodoxy, therefore, and religion more widely, have changed significantly over the course of the decades since the collapse of communism and the erosion of the state’s regulative powers over society; much more and quite differently than what the massive affiliation statistics tend to show. In what follows, I examine in some detail some of these changes, from within Orthodoxy to the rise of New Age ‘spiritualities’ and Pentecostalism from the perspective of the embedment within the Global-Market regime.

The Neoliberalisation of Orthodox theologies

In his book in Romanian entitled The Anti-Social Apostolate. Theology and Neoliberalism in Post-Communist Romania, Alexandru Racu analyses the ‘writings of some of the most prominent Orthodox intellectuals and theologians from Romania’ and shows how ‘new religious arguments and narratives depart from previous Orthodox tradition and practice’ (Gog, 2011: 93) to align with neoliberal tropes. In his review in English, Gog notes how the Orthodox ethic has historically been deemed ‘incompatible with social modernization’ (ibid.) and capitalism, namely because of its pronounced other-worldly orientation, social emphasis, and rejection of the private appropriation of wealth. Eastern Orthodoxy has not produced a modern aggiornamento as the Catholic Church has with the Second Vatican Council. This makes the innovations of the last few decades even more stunning, especially coming from such prominent intellectual figures. Racu exposes for instance ‘Patapievici’s arguments in favour of the sanctity of private property, the redemptive nature of markets and their capacity to transform “private vices into public virtues”, [and] the religious valorisation of individual entrepreneurialism’. The same goes for ‘Baconschi’s attempt to build a Christian Democracy based on a subsidiarity principle in detriment to the social solidarity principle, his religious defence of a minimal state and the “moral” requirement of welfare retrenchment’. Finally, Racu underlines ‘Neamtu’s theological development from Christian socialism to the endorsement of spiritual entrepreneurialism, religious moralization of success and motivational programs that equip the religious believer with the necessary tools to create profitable entreprises.’ (Gog, 2017: 125; Racu, 2017) Other examples presented by the author are less blatant yet show how market ideologies have penetrated theological discourse, producing contradictions, confusions, and incoherence in the Church’s social doctrine. Contrary to the Greek Orthodox Church, the Romanian Orthodox Church (RoOC) did not condemn or critique the neoliberal reforms in Romania, neither did it distance itself from these public theologians, perhaps because ‘their symbolic capital was used […] for cleaning its public image in the wake of recurrent criticism for its collaboration with the communist regime.’ (Gog, 2017: 126; Racu, 2017) There are questions as to how much these elite discourses resonate with the everyday beliefs and practices of Romanian Orthodox, but there is little doubt on how they have provided ‘religious and cultural legitimations of capitalism’ after the fall of communism, and how they have given ‘extensive credit to the implementation of one of the most radical neo-liberal projects in Central and Eastern Europe.’ (Gog, 2017: 121; Racu, 2017) In any case, it can be said that this new strand of theological discourse now competes with the more traditionalist-nationalist currents analysed above, obliging them to respond to economic issues.

Such developments are not confined to Romania. Victoria Fomina reports how the highest officials of the ROC have also had to acknowledge the exigencies of the new market determined environment (Fomina, 2018). A movement within the Church now denounces its ascetic legacy, valorisation of the virtues of poverty, and traditional contempt for earthly life, and pleads for a this-worldly compatible Orthodoxy. Tensions have therefore arisen within the Church between those who condemn excessive wealth and those who provide legitimation for it. These debates have been heated by the fact that the Church is increasingly involved in commercialising its services and selling religious items and services. Laity movements have also denounced traditional other-worldliness as a cause for dependency and laziness in order to promote entrepreneurialism. Fomina reports the formation of the Union of Orthodox Entrepreneurs (UOE) in St Petersburg, which has worked on the elaboration of an Orthodox business code of conduct that both legitimates entrepreneurialism while providing a specifically Orthodox ethical frame to orient economic success. As one member puts it, the idea is to ‘work honestly in the pursuit of one’s self-interest’ (quoted in Fomina, 2018) or, in the words of another, to ‘earn a million in the glory of God.’ (quoted in Fomina, 2018) Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the UOE has attempted to forge a brand of Orthodox finance based on the model of Islamic finance (Rudknyckyj, 2019), although rather unsuccessfully for the moment. It is indeed interesting to note how Islam has been able to convert itself more easily into blatantly marketised forms than Orthodox Christianity (Makridès, 2018; on Islam see Gauthier, 2018). Yet other transformations are taking place which show how Orthodoxy is being lifestyled and reshaped within Global-Market parameters, yet in less blatant and direct ways.

Consumerism and the ethics of authenticity

The adoption of consumerism and the shift of the meaning of progress, as something formerly part of the State’s mission and devolved today to the Market, is constitutively ambivalent. Post-communist and post-Soviet countries now show great openness to global flows and influences, especially when set in contrast with the communist or Soviet space. The citizens of these countries are torn between the hopes of rising up to Western standards and the fear of declining to Third World status (Patico, 2001; Stryker & Patico, 2001). This makeup is also constitutive of the religious landscape. While the latter attitude is echoed in conservative and neo-nationalist responses, more positive and pro-active attitudes to globalisation and capitalism shape the following phenomena.

One common trait across the board is the embracing of consumerism. In Russia, for instance: ‘New consumer and cultural standards […] have gathered momentum throughout the post-Soviet period.’ (Agadjanian and Rousselet, 2016: 48) Orthodoxy’s conservative response does not mean that people have resisted the pull of consumerism, on the contrary. Another response has been the reconfiguration of Orthodoxy into a ‘genre of identity’: i.e. a ‘“genre of expression, communication and legitimation” of collective and individual identities’ (Agadjanian & Roudometof, 2005: 7, quoting Robertson, 1992), by which religion is rediscovered as a ‘cultural resource for identity’ (ibid.) in a global world. This trend, which is sometimes enmeshed with the conservative-nationalist response, refashions religion so that it caters not only to collective but also personalised identities. Across OMEE countries, religion has been ‘rediscovered […] as a new narrative of, or a cultural resource for, identity.’ (ibid.) As religion becomes de-differentiated, it becomes intertwined with ethnic, kindred, cultural, local, and class identities.

Orthodoxy as a genre of identity signifies that it is increasingly made to cater to the ethics of authenticity and the quest for self-realisation through the exercise of choice in religious and spiritual matters: ‘In line with a global trend that has partly affected the Russian cultural landscape, “religion,” in a significant shift, has now become a highly-individualized expression of non-rigid, flexible quests that do not claim “universal and eternal” validity.’ (Agadjanian and Rousselet 2006: 30) While these trends are less obvious than in the West, they are nevertheless reinforcing with time. A plurality of ‘non-denominational, small-scale, or even individual religion and “new religious movements”’ (ibid.) entered the OMEE religious landscape in the immediate aftermath of the communist collapse, including born-again evangelical groups like Pentecostals, Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Baptists, Adventists, Brethren Assemblies, and the Hare Krishna (see also Gog, 2006, 2011). While their success has been limited, and while they have been critiqued by the Orthodox Church and public opinion, they have contributed to introduce experiential types of religiosity in OMEE countries. Similarly, the culture of self-expression, self-development, and self-realisation has been rapidly expanding since the 1990s, and Neo-pagan, Neo-shamanic, and New Age movements have been growing at the same rate as in ‘rest of Europe and North America.’ (Ferlat, 2003: 45) Ideas of ‘letting the integral voice of each individual express itself after freeing the self from one’s conditioning’ (Ferlat, 2003: 40) have circulated increasingly within popular and mainstream culture, disseminated by popular New Age, management, Self-Help, and pop psychology literature. The case of Russian Neo-pagans illustrates how Neopaganism is a transnationally operating movement founded on a set of shared beliefs, practices, and inspirational authors (Carlos Castaneda, Michael Harner) that nevertheless takes on local-specific contents. For instance, references to Slavic traditions and/or Siberian and Altaï shamanism as well as pre-Christian folk traditions are summoned in order to provide sources of authenticity for their particular self-realisation and self-expressive projects (Ferlat, 2003).

New Age religiosity has been particularly fashionable in urban centres such as Moscow and St Petersburg. The Russian case exemplifies how the personalisation of religiosity and its alignment on the ethics of authenticity and expressivity have affected cities more than rural areas, and the middles classes and elite more than the working and peasant classes. In her study of the religiosity of Russian university students born in the 1990s, Polina Batanova (2018) has found that the importance of individual choice in matters of faith and morality is a structural characteristic that is transversal to all types of religiosity, and that not being able to choose (the ultimate consumerist value) is felt to be a major factor of exclusion and frustration. She also notes how a utilitarian logic underscores the responses she collected, as religion is cast as an answer to personal needs of commitment, identity, belonging, and ethics. This data allows that we refine the aforementioned statement according to which strong affiliation with Orthodox Christianity is negatively correlated to the degree of participation in global flows and consumerism. In general, then, lower classes, rural areas, as well as crisis-stricken industrial areas are more prone to adhere to the conservative religious reaction and show high levels of adherence to a traditionalist type of Orthodoxy. Inversely, religion as a genre of identity tends to be overrepresented in globalised and urban social milieus. In my view, there are strong arguments in support of the idea that the case of Russia is exemplary of wider trends across OMEE countries, with national variations.

Marketisation and the rise of magic

The shift to the Global-Market era has coincided with the ‘return’ and efflorescence of ‘magic’ practices, esotericism, exorcism, and a wide array of healing techniques in what can be diagnosed as a form of ‘re-enchantment’ (Testa, 2017). Magic practices with traditional roots managed to survive in the underground during the Soviet and communist period, yet their present—striking and ubiquitous—revival blends with more recent New Age-derived developments. According to anthropologist Galina Lindquist: ‘Practices of magic and healing in contemporary Russia are widespread, resorted to by all social strata and population groups. They are a firm part of everyday strategies of survival for many people, irrespective of their income bracket or education level.’ (Lindquist, 2001: 98) Only firm-believing Orthodox and atheists condemn these practices as Satanic or fraudulent, and they have proliferated somewhat outside public, media, and state attention. Nevertheless, practises such as house or car blessings by Orthodox priests have become widespread among all types of Orthodox-affiliated. As in other parts of the globe, the marketisation of post-socialist societies has opened the door to the revival of magic practices, in and outside mainstream denominations (Gauthier, 2020).

The shift from socialism to capitalism has come with a formidable reversal of the meaning of and attitudes towards money. Considered as dirty and the source of immorality in Soviet times, while money-making activities were even criminalised by the state, money has suddenly been thrown at the centre of personal and social lives and promoted as the key to all aspirations: ‘with the arrival of the market, money has become the primary, if not the only, means of survival, devaluating and attenuating [the] old networks of trust’ that used to be the means by which people secured access to ‘material and social goods’ (Lindquist, 2001: 99). Similarly, money has become a major concern for all types of religion. We have seen above how entirely novel prosperity theologies and legitimations for property were emerging in the very heart of the Orthodox Church, notwithstanding its recurrent cries against the immorality of ‘the West.’ Money has also emerged as one of the principal issues addressed in magic practices, along with matters of love, family, and health (Lindquist, 2000: 324).

The importance of money, furthermore, accompanies a process of horizontalization or immanentisation of transcendence: ‘money is seen as a manifestation of the divine force, a variety of magical flow connecting cosmos and the human being. Indeed, in the life of contemporary Russians, money is the sole prerequisite of any kind of acceptable social existence. It indexes not only relations with the divine power, but also the crucial human connections of kinship and friendship.’ (Lindquist, 2000: 325) Lindquist’s analysis of money in relation to magical flow and divine force recalls Marcel Mauss’ (1950) famous notion of mana, which he put at the centre of religious practices, exchanges, concerns, and beliefs, and which he similarly associated with money. In Russia as in the vast majority of post-communist countries, access to healthcare and education are more or less, if not entirely, hinged on financial resources. ‘Lack of money’, incidentally, ‘and a pressing need to earn it, is a constant strain of Russian everyday life.’ (Lindquist, 2000: 326) In post-socialist countries, the social net, once universal, free, entirely state-owned and state-directed, has been dismantled, privatised, reformed, and marketised even more radically and more profoundly than in the West. Religious and magic practises made to favour success are therefore a coextensive development tied to the brutal turn to capitalism.

The Global-Market regime opens onto a re-enchanted landscape in which the here and now, health, and success succeed to soteriologies oriented towards salvation in the after-world or a collective utopia.

Creating neoliberal subjectivities: The New Age explosion

For Irena Borowik (2002), the spread of New Age was already one of the major dimensions of the wider religious transformations in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine at the turn of the millenium. This argument is supported by the results of a recent research project conducted in Romania on ‘alternative spiritualities’ and personal development, and can serve to illustrate the situation in the wider OMEE region. While New Age-derived ‘alternative spiritualities’ were virtually absent in Romania barely fifteen years ago, they have erupted since, penetrating deeply into ‘popular Romanian culture’ (Gog, 2016: 98) by the way of books, television, the Internet, newspapers, and magazines. The phenomenon gathered momentum in the wake of Romania’s integration in the European Union in 2007 and the ensuing 2008 financial and economic crisis. Over a very short period of time, alternative spiritualities have moved from the margins to the mainstream as they have become incorporated and institutionalised in various professional fields, including psychology, management, governmental agencies, healthcare, and welfare. Sorin Gog writes: ‘Alternative and complementary medicine is [no longer] subterranean, esoteric and something that popular healers perform in their private practice, it is something that has been introduced in mainstream medical establishments’, like ‘spiritual healing and meditation techniques’ (Gog, 2016: 122) in hospital oncology departments for example. Meanwhile, a ‘massive outburst of spirituality has taken place in the field of psychology’ (ibid.) as part of a paradigm shift that has seen cognitive-behavioural approaches subjected to an increasing amount of critique in favour of New Age-inspired holistic approaches. As for the world of business, spiritually-infused personal development programs are becoming a passage obligé for the acquisition of career-enhancing ‘soft skills’ (communication, self-presentation, the ability and willingness to learn new things and grow as a person) (Gog & Simionca, 2016; Simionca, 2016; Szabo, 2016; Tobias, 2016; Trifan, 2016). These trends have become important among professionals in fields as varied as ‘economists, lawyers, teachers, creative workers, service specialists, IT-personnel, engineers, experts, consultants, etc.’ (Gog, Forthcoming).

Gog connects this efflorescence to deeper cultural motifs and other social trends, themselves linked to the developments of capitalism. Analysing surveys that were ‘not designed to reveal the growing interest in a variety of forms of alternative spirituality’ (2016: 104), he manages to draw the following conclusions. First, even though these trends are generalised, there is a marked difference in the answers given by cohorts born after 1981, which were not socialised under the communist regime. He notes a substantial decrease in the belief in a personal God and the sharp rise in the belief in a ‘spiritual or life force’ for those born in 1981 and 1990 (28,3% versus 54,3% respectively). Gog similarly notes ‘a gradual decline of institutionalised religion’ among younger generations especially, as well as ‘an increased perception that the church does not offer adequate answers to their religious quests’, and ‘a tendency to separate the church from social and political matters.’ (p.108) Religion no longer depends on socialisation within the family, while the authority of the priest and the church erodes. Gog argues that these survey results do not support secularisation as much as ‘a growing interest in spirituality’ (p.114) under capitalist conditions. In other words, the results show a religious landscape in which de-institutionalised and individualised forms of religiosity (spirituality) are becoming dominant. Interestingly, the younger generations are also more prone to have democratic values and to be entrepreneurial and market-oriented. For Gog, the spectacular rise of interest in New Age-derived ‘spiritualities’ and healing techniques are not an epiphenomenon: they signal ‘a profound and […] radical change structural change in the religious field.’ (p.120) In the words of Gog, we are in the face of a ‘deep and radical transformation of the language and religious ontology’ of the whole Romanian religious landscape. He argues that this is not a simple change in substance, or content of belief: it is a change in the very structure or form of religion: ‘The new spiritual field has mediated a new sense of the subject, a new structure of temporality, new modes of religious socialization, and a new relation to worldliness—all of these constituting radical transformations of how traditional and modern religious fields have been operating in Romania in the last decades’ (p.99), even beyond urban areas (Rusu, 2017).

While the contours of the rise of alternative spiritualities and other self-help, self-realisation, and healing practices are ill-defined, they are perhaps best labelled under New Age. In the West, New Age was born in the midst of the consumerist revolution of the 1960s and was an integral part of the ‘countercultural’ movement. As such, its initial politics were clearly anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and anti-materialistic. It also voiced a critique of work (as alienating and lacking in authenticity) and utilitarian individualism, even while it shifted concerns from collective transformations of society via political projects to transforming society through the realisation of individuals. New Age grew well-beyond the confines of the original movement yet continued to show a critical stance towards capitalism until the 1980–90s. It is then, amidst the neoliberal revolution and the transformation of capitalism into its financialised and globalised avatar, that New Age derived religiosities and therapeutics increasingly legitimised a post-materialist version of the health and wealth gospel. It is also in this period that techniques such as meditation and yoga started to become integrated in corporate management, and that self-realisation and self-perfecting through work became mainstreamed.

It is remarkable how quick both anti- and pro-capitalist (or neoliberal) brands of New Age were embraced in Eastern Europe, which had been largely (but not totally) isolated from this history until the collapse of communism. While New Age spiritualities that retain a critical edge towards capitalism and consumerism have flourished in the margins of Eastern European societies (Palaga, 2016), a capitalist-friendly brand of New Age has blossomed in professional domains that have ensured it a much higher level of impact within the mainstream. The difference between these two brands of New Age lies in the emphasis placed by the latter on the sole individual at the expense of communal bonds and wider social issues. As Gog explains: ‘Relying on one’s own self is the single resource needed in order to experience spiritual fulfilment, a lack of autonomy and a lack of spiritual maturity: the whole idea of spiritual development is to become a pro-active person capable of finding the inner resilience to overcome the obstacles of life and if this does not happen, to become invulnerable to them and experience in yourself the needed Presence and Peace.’ (Gog, 2016: 118) This contrasts with what I call countercultural New Age, which emphasises how healing oneself emerges from the act of helping others to heal, and which more readily fosters and values communal and others-oriented experiences.

The annexation of New Age religion in the workplace leads to a paradox since it binds personal realisation and emancipation to productivity and professional loyalty. In the words of Emma Bell and Scott Taylor, this ‘ensures that the search for meaning is harnessed to specific organizational purposes,’ and translates existential questions into technical issues of ‘self and organizational management.’ (Bell & Taylor, 2003: 332) By making individuals responsible for their well-being and happiness, workplace spirituality also shelters the organisation and the wider socio-economic context from critique. New Age emerges as both the religious response to and one of the main means of legitimation of neoliberalism and its promotion of an entrepreneurial self that shares in the virtues of ‘individual creativity, flexibility, self-reliance and self-development.’ (Gog, Forthcoming) As a result, the ‘strong emphasis on spiritual entrepreneurialism makes the field of alternative spiritualities one of the most radical vectors [for] generating popular cultural legitimation [of] contemporary neo-liberal transformations that have been prevalent in [Central and Eastern European] countries.’ (ibid.) In other words, New Age produces and socialises a type of subjectivity that is aligned with the requirements of the new globally enmeshed socio-economic environment brought on by neoliberal reforms and the spread of consumerism. It also promotes a type of spirituality in which well-being and prosperity become fused in the ‘hero-ised’ figure of the entrepreneur who sees change, difficulties, and mobility as opportunities for career, personal, and spiritual development (e.g. Szabo, 2016).

The social and economic context within which New Age spiritualities emerged in Romania is clearly one of profound transformation following the radical implementation of neoliberal reforms composed of austerity measures and labour market liberalisation. These dramatically decreased the number of collective agreements, introduced short-term contractual employment, made dismissals easier, and ushered in a new highly competitive and precarious working environment. In this context, New Age-derived spiritualities have ‘produced new cultural cosmologies that creatively engaged with the dynamic transformations of everyday life and generated new religious practices of the self and innovative religious technologies of self-development that became especially attractive for segments of the urban educated strata that was losing interest in traditional forms of institutionalised religions.’ (Gog, Forthcoming) The coincident rise of alternative spiritualities and deep marketisation, in other words, is not coincidental but a structural characteristic of the shift from state-led communism to global capitalism.

Creating neoliberal subjectivities: Pentecostalism and orthodox Christianity