Abstract

This paper analyzes how financial literacy and reported willingness to take financial risk impact a household’s choice of mortgage type. The results show that households reporting higher financial literacy and lower risk aversion are 55 to 97 % more likely to opt for interest-only mortgages. The results are robust to alternative explanations such as the involvement of financial advisors, the effect of peers, experience with prior home-ownership, and house price expectations. In general, alternative mortgage products, as opposed to traditional mortgages, are chosen by wealthier, older, and/or more sophisticated households that are more likely to have a greater understanding of the risks and benefits associated with these products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Recourse debt holds households liable for complete repayment of their mortgage in case a foreclosure occurs and proceeds fall short of the outstanding balance. Strategic default is therefore never a valuable option as the costs always exceed the benefits.

The intuition behind this result is that the interest-rates on FRM contracts incorporate a term premium and are therefore less appealing to households who are currently borrowing-constrained or are more likely to move in the near future. Since they are generally younger, they are expected to choose ARM mortgages ceteris paribus, to take advantage of the lower initial interest rate.

See for a more elaborate discussion Schober and Conrad (1997).

The number of observations per quartile is not equal to 25 % of the total because household wealth and the corresponding quartile are computed year by year allowing for the possibility of transition to another wealth quartile.

Unlike for example the U.S., origination fees in the form of points are non-existent in the Netherlands. Upon origination, lenders and intermediaries receive compensation through provisions which are calculated as a percentage of the initial balance. Inclusion of the interest rate and the size of the balance in our analyses ensures that effects due to pricing differentials are taken into account.

The increase in average household income is taken into account. Average income amounted to €32.500 in 2009, compared to only €21.780 in 1994. Low income is defined as households with an annual reported income below national average. Medium incomes are defined as households with an average up to twice the average income, and high-income are those households whose income exceeds twice the average income.

Financial advisors are often paid on commission base and might impact the decision process according to the incentives provided to them (Inderst and Ottaviani 2009) rather than truthful and honest information disclosure. In additional analysis, we find no bivariate dependence between advisor involvement and contract choice.

Negative amortization contracts and ‘subprime’ mortgages (e.g. 2/28 ARM’s) are not available in the Netherlands.

We have chosen an endowment mortgage as an example of a deferred amortization-type. Life-annuity and investment mortgages work in a similar way.

Fixed term agreement for long term call option on existing securities, which is an option or warrant on an existing security with an extended maturity.

References

Authority of Financial Markets. (2008). AFM Consumenten Monitor Q3 2008 [in Dutch], online available at http://www.afm.nl/nl/consumenten/actueel/brochures/~/media.

Barber, B., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be Boys: gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292.

Brown, J., Ivkovic, Z., & Smith, P. (2008). Neighbors matter: causal community effects and stock market participation. Journal of Finance, 63, 1509–1531.

Brueckner, J., & Follain, J. (1988). The Rise and fall of the ARM: an econometric analysis of mortgage choice. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(1), 93–102.

Bucks, B., Pence, K. (2006). Do Homeowners Know Their House Values and Mortgage Terms? Working paper, Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

Calvet, L., Campbell, J., & Sodini, P. (2009). Measuring financial sophistication of households. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 99(2), 1–4.

Campbell, J. (2006). Household Finance. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1551–1604.

Campbell, J., & Cocco, J. (2003). Household risk management and optimal mortgage choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1449–1494.

Chang, L., & Krosnick, J. (2009). National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(4), 641–678.

Chang, Y., & Yavas, A. (2009). Do borrowers make rational choices on points and refinancing? Real Estate Economics, 37(4), 635–659.

Chiang, Y., Sa-Aadu, J. (2013). Optimal Mortgage Contract Choice Decision in the Presence of Pay Option Adjustable Rate Mortgage and the Balloon Mortgage, forthcoming in Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics.

Cocco, J. (2005). Portfolio choice in the presence of housing. Review of Financial Studies, 18(2), 535–567.

Cocco, J. (2013). Evidence on the Benefits of Alternative Mortgage Products. Journal of Finance, 68(4), 1663–1690.

Cocco, J., Gomes, F., & Maenhout, P. (2005). Consumption and Portfolio Choice over the Life Cycle. Review of Financial Studies, 18(2), 491–533.

Collins, M. (2010). A Review of Financial Advice Models and the Take-Up of Financial Advice, Working Paper WP10-5, Center for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Coulibaly, B., & Li, G. (2009). Choice of mortgage contracts: evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Real Estate Economics, 37(4), 659–674.

Cunningham, D., & Capone, C. (1990). The relative termination experience of adjustable to fixed-rate mortgages. Journal of Finance, 45(5), 1687–1703.

De Haan, L., & Sterken, E. (2011). Bank-specific interest rate adjustment in the dutch mortgage market. Journal of Financial Services Research, 39, 145–159.

Demyanyk, Y., & Van Hemert, O. (2009). Understanding the subprime mortgage crisis. Review of Financial Studies, 24(6), 1848–1880.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review, 100, 1238–1260.

Donker, B., & Van Soest, A. (1999). Subjective measures of household preferences and financial decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20, 613–642.

Duca, J., & Rosenthal, S. (1994). Do Mortgage Rates Vary Based on Household Default Characteristics? evidence on rate sorting and credit rationing. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 8, 99–113.

Elliehausen, G., Lundquist, C., & Staten, M. (2007). The Impact of credit counseling on subsequent borrower behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41(1), 1–28.

Elmerick, S., Monalta, C., & Fox, J. (2002). Use of financial planners by US households. Financial Services Review, 11, 217–231.

Federal Reserve Board. (2007). Testimony of Roger T. Cole, Division of Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, United States Senate, March 22, Washington DC.

Fratantoni, M. (1999). Reverse mortgage choices: a theoretical and empirical analysis of the borrowing decisions of elderly homeowners. Journal of Housing Research, 10(2), 189–208.

Gerardi, K., Rosen, H., & Willen, P. (2010a). The Impact of deregulation and financial innovation on consumers: the case of the mortgage market. Journal of Finance, 65(1), 333–360.

Gerardi, K., Goette, L., Meijer, S. (2010b). Financial Literacy and Subprime Mortgage Delinquency: Evidence from a Survey Matched to Administrative Data, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2010–10.

Goetzmann, W., & Kumar, A. (2008). Equity Portfolio Diversification. Review of Finance, 12, 433–463.

Grinblatt, M., Keloharju, M., & Linnainmaa, J. (2011). IQ and Stock Market Participation. Journal of Finance, 66(6), 2121–2164.

Grinblatt, M., Keloharju, M., & Linnainmaa, J. (2012). IQ, trading behavior, and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(2), 339–362.

Guiso, L., & Japelli, T. (2005). Awareness and stock market participation. Review of Finance, 9, 537–567.

Hackethal, A., Haliassos, M., & Japelli, T. (2012). Financial advisors: a case of babysitters? Journal of Banking and Finance, 36(2), 509–524.

Harrison, D., Noordewier, T., & Yavas, A. (2004). Do riskier borrowers borrow more? Real Estate Economics, 32(3), 385–411.

Hilgert, M., Hogarth, J., Beverly, S. (2003). Household financial management: the connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin July, 309–322.

Hong, H., Kubik, J., & Stein, J. (2004). Social interaction and stock-market participation. Journal of Finance, 59, 137–163.

Inderst, R., & Ottaviani, M. (2009). Misselling through agents. American Economic Review, 99(3), 883–908.

Kau, J., & Keenan, D. (1987). Taxes, points and rationality in the mortgage market. Real Estate Economics, 15(3), 168–184.

Koijen, R., Van Hemert, O., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2009). Mortgage timing. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 292–324.

Korniotis, G., & Kumar, A. (2011). Do Older investors make better decisions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 244–265.

LaCour-Little, M., & Yang, J. (2010). Pay me now or pay me later: alternative mortgage products and the mortgage crisis. Real Estate Economics, 38(4), 687–732.

Lee, J., & Hogarth, J. (1999). The price of money: consumers’ understanding of APRs and contract interest rates. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 18(1), 66–76.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2007a). Baby boomer retirement security: the role of planning. Financial Literacy and Housing Wealth, Journal of Monetary Economics, 54, 205–224.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2007b). Financial Literacy And Retirement Preparedness: Evidence And Implications For Financial Education. Business Economics, 42, 35–44.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: how do women fare? American Economic Review, 98(2), 413–417.

Mandell, L., & Klein, L. (2009). The impact of financial literacy education on subsequent financial behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 20(1), 15–23.

Miles, D. (2004). The UK Mortgage Market: Taking a Longer-Term View, final report for the UK Treasury Department.

Moore, D. (2003). Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: Knowledge, behavior, attitudes and experiences, Technical Report: 03-39, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Washington State University.

Morin, R., & Suarez, F. (1983). Risk aversion revisited. Journal of Finance, 38(4), 1201–1216.

Mullainathan, S., Nöth, M., Schoar, A. (2010). The Market for Financial Advice: An Audit Study, Working Paper accessible at http://dev3.cepr.org/meets/wkcn/5/5571/papers/N%c3%b6thFinal.pdf.

Nosić, A., & Weber, M. (2010). How riskily do i invest? the role of risk attitudes, risk perceptions, and overconfidence. Decision Analysis, 7(3), 292–301.

Nunnally, C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

Quercia, R., & Spader, J. (2008). Does homeownership counseling affect the prepayment and default behavior of affordable mortgage borrowers? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(2), 304–325.

Sa-Aadu, J., & Sirmans, C. (1995). Differentiated Contracts, Heterogeneous Borrowers and the Mortgage Choice Decision. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 27(2), 498–510.

Schober, M., & Conrad, F. (1997). Does conversational interviewing reduce survey measurement error? Public Opinion Quarterly, 61, 576–602.

Schooley, D., & Worden, D. (1996). Risk aversion measures: comparing attitudes and asset allocation. Financial Services Review, 5(2), 87–99.

Shum, P., & Faig, M. (2006). What explains household stock holdings? Journal of Banking and Finance, 30, 2579–2597.

Stanton, R., & Wallace, N. (1998). Mortgage choice: what’s the point? Real Estate Economics, 26, 173–205.

Stanton, R., & Wallace, N. (1999). Anatomy of an ARM: the interest rate-risk of adjustable rate mortgages. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 19, 49–67.

US Government Accountability Office. (2006). Alternative Mortgage Products. Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Housing and Transportation, Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, US Senate. GAO-06-1021, Washington DC.

van Hemert, O. (2010). Household interest rate risk management. Real Estate Economics, 38(3), 467–506.

van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101, 449–472.

Woodward, S., & Hall, R. (2010). Consumer Confusion in the mortgage market: evidence of less than a perfectly transparent and competitive market American. Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 100, 511–515.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the editor James Kau, two anonymous referees, Dion Bongaerts, Eric Duca, Andra Ghent, Melissa Porras Prado, Avichai Snir, Manuel Vasconcelos, Vincent Yao and seminar participants at the Rotterdam School of Management, the AREUEA Mid-Year Meeting (2011), the Understanding Societty Meeting (2011) and the Third ReCAPNet Conference (2011) for valuable comments. We thank the National Mortgage Guarantee (Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woning) for financial support. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are solely the author’s and do not reflect the official view, policy or position of the AFM, its Board of Directors, or any other Dutch government agency.

Appendix

Appendix

Mortgage products in the Netherlands

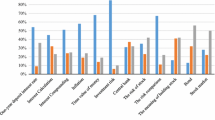

This appendix discusses the differences between available mortgage types in the Netherlands in detail as well as the distribution of origination over time. Mortgage interest payments are fully deductible at the marginal income tax-rate (typically 42 or 52 %), but amortization payments are not a tax-deductible item. Maximization of tax-benefits therefore requires that any amortization charges are not directly deducted from the outstanding principal as this lowers the deductibility of interest-rate payments as well. The two mortgage categories that cater to this tax-arrangement are deferred amortization – where a household saves in a separate account for a balloon payment at maturity – and interest-only products, were no amortization payments prior to maturity are made.Footnote 8 Although hybrid mortgages are available in the Netherlands (e.g., a combination of an annuity and endowment mortgage), they constituted only a minor part of the sample (less than 5 %) and they are classified here as one type based on the size of the principal of the individual mortgage relative to total outstanding mortgage debt. Our classification of the different available contracts in the dataset is shown in Table 10.

To illustrate how the affordability and amortization develops, we compare after-tax payments in year one and after 15 years for three different mortgage types in Table 11.Footnote 9 A traditional amortizing annuity contract immediately starts repaying, and this amortization constitutes an increasing proportion of the total mortgage expenses. The outstanding balance decreases steadily until the mortgage is completely paid off at maturity. Consequently, the tax-benefit of interest payments decreases as they fall in tandem with the lowered outstanding principal, while amortization payments are not tax-deductible.

In the case of an AMP the repayment of the principal is deferred towards the future. The example in the table assumes an endowment mortgage. Instead of directly subtracting the amortization-payments from the principal, the repayment of the principal is converted to an annuity and the endowment payment goes into an endowment fund. In this case the 200,000 euro liability due after 30 years is annuitized, assuming that the endowment-fund will yield an average return of 6 % over the term, with the yearly endowment in this case amounting to 2,530 euro, which is lower than the 3,278 euro amortization payment on an annuity-mortgage. As the outstanding balance is not repaid, the benefits of tax-deduction are not decreasing, but instead the mortgage is paid off at maturity with the proceeds of the endowment fund. Finally, the interest-only mortgage – as implied by its name – only features interest-expenses until maturity. At maturity the proceeds of a sale of the collateral, private savings, or a refinancing of the mortgage, should suffice to pay off the principal. Again, this construction maximizes the benefits of tax-deductibility. It can also be seen that the net-yearly charges in year one are highest for traditional amortizing contracts (8,498 euros), followed by endowment (7,750 euros) and interest-only mortgages (5,220 euros), hence the name ‘affordability’ mortgages.

The downside of the affordability is the increased repayment risk of AMP’s, assuming that households are able to honor their obligations till maturity. If the return on the endowment fund is lower than the anticipated 6 %, the terminal value of the fund will be insufficient to repay the mortgage at maturity (i.e. a 5.5 % return will lead to a shortfall of more than 16,000 euro at maturity). For interest-only mortgages the risk is – all else equal– even higher as the borrower is dependent on the value development of his property until maturity or his personal wealth.

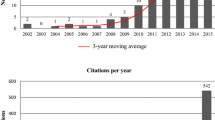

Figure 1 plots the distribution of newly originated mortgages between 1994 and 2009. There is a substitution effect in newly originated mortgage types from traditional mortgages towards interest-only contracts similar to patterns observed in the U.K. The share of interest-only contracts in the total product mix rose from 3 % in 1994 to 45 % by 2009. This massive increase in popularity is primarily driven by the aforementioned tax-regime, rising house prices and low interest rates, as the demographic characteristics of new borrowers remained constant during the same period.

Measurement of Risk Aversion and Financial Literacy

For the analysis of the impact of financial literacy, risk aversion, and opinions about the current and future situation on mortgage choice, several questions from the DNB Household Survey were used. The exact wording of these questions is presented here.

Risk Aversion measures

All questions could be answered on a seven-point scale ranging from 1, totally disagree with the statement to 7, totally agree.

The resultant scale was constructed by recoding the responses on risk aversion measures 3, 5, and 6 and adding them up together, thereby creating one scale that can range from 6 (very risk tolerant) to 42 (very risk averse). Analysis of the scale using the Cronbach Alpha measure shows that the scale could not be improved by deleting items and the coefficient of 0.927 exceeds the 0.90 level that Nunnally (1978) suggested as a threshold for scales used in decision-making processes.

Financial Literacy measures

Self-reported financial knowledge

Respondents were asked to respond to the following statement:

“How knowledgeable do you consider yourself with respect to financial matters?”

With response categories:

-

1.

Not knowledgeable

-

2.

More or less knowledgeable

-

3.

Knowledgeable

-

4.

Very knowledgeable

Financial active

Financial activity is measured using the following seven questions:

-

1.

“Did you, on 31 December [year], have investments with MUTUAL FUNDS? Do not include investments in growth funds, investments (shares, bonds) in companies, or insured saving (i.e., saving through a life-insurance) here.”

-

2.

“Did you, on 31 December [year], have any BONDS and/or MORTGAGE BONDS? Do not include bonds through mutual funds here. These have already been reported on.”

-

3.

“Did you, on 31 December [year], own any SHARES? Do not include shares of your own private limited company here, nor bonds through MUTUAL FUNDS. These have already been reported.”

-

4.

“Did you, on 31 December [year], have one or more PUT-OPTIONS?”

-

5.

“Did you have any written PUT-OPTIONS outstanding on 31 December [year]?”

-

6.

“Had you, on 31 December [year], bought one or more CALL-OPTIONS, FALCONS, or WARRANTS?”

-

7.

“Did you have any written CALL-OPTIONS, FALCONSFootnote 10 or WARRANTS outstanding on 31 December [year]?”

Responses are recorded as a dummy variable equaling 0 (= no) if the household did not hold the security at 31 December and 1 (= yes) if the household did hold the security. Final scores were obtained by counting the total number of yes-responses, resulting in a scale that ranges between 0 and 7, where 0 indicates that the household does not hold financial assets at all, while 7 indicates that the household holds all mentioned securities.

-

Risk Aversion 1:

“I think it is more important to have safe investments and guaranteed returns, than to take a risk to have a chance to get the highest possible returns”

-

Risk Aversion 2:

“I would never consider investments in shares because I find this too risky”

-

Risk Aversion 3:

“If I think an investment will be profitable, I am prepared to borrow money to make this investment”

-

Risk Aversion 4:

“I want to be certain that my investments are safe”

-

Risk Aversion 5:

“I get more and more convinced that I should take greater financial risks to improve my financial position”

-

Risk Aversion 6:

“I am prepared to take the risk to lose money, when there is also a chance to gain money”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cox, R., Brounen, D. & Neuteboom, P. Financial Literacy, Risk Aversion and Choice of Mortgage Type by Households. J Real Estate Finan Econ 50, 74–112 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9453-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9453-9