Abstract

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric condition with chronic evolution, one of the most disabling diseases. The main cause for the disease’s progression is considered to be the lack of compliance with the treatment. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an important treatment option for patients with schizophrenia. Olanzapine long-acting injection (OLZ-LAI) is a pamoate monohydrate salt of olanzapine that is administered by deep intramuscular gluteal injection. The aim of this paper is to report the effects of a sudden and unplanned switch from olanzapine long-acting injectable to oral olanzapine in remitted patients with schizophrenia due to restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. An observational study conducted in the Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry and Neurology of Brasov, Romania between April 2020 and March 2021. 27 patients with OLZ-LAI were entered into the study. Of 27 cases, 21 patients preferred to be switched to oral olanzapine (77.77%). Only 6 patients continued with the long-acting formulation. The main reason for the initiation of olanzapine pamoate in all the patients was non-adherence to oral medication (80.95%), and the mean age of starting LAI olanzapine was 36.42 years (SD ± 10.09). Within the following 12 months after switching from olanzapine LAI to OA, 15 patients (71.42%) relapsed, and 12 were admitted to the emergency psychiatric unit. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought multiple disservices to current medical practice. Sudden and unplanned switch from olanzapine long-acting formulation to oral olanzapine was followed by the high rate of relapse in remitted schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric condition with a chronic evolution and a disabling disorder. One of the well-established cause for the disease’s progression is antipsychotic nonadherence.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an important treatment option for patients with schizophrenia who have difficulties in adhering to oral regimens. Long-acting formulations ensure that the patient has received the treatment. Since regulations require that the injections are administered in healthcare facilities, it is immediately known when the patient does not return for treatment [1, 2].

The paradigm for LAIs has changed from the early 2000s, when LAIs were recommended for non- adherent patients or for patients with multiple relapses. The new guidelines recommend these formulations as the treatment of choice as soon as possible after the onset of schizophrenia, in order to avoid relapses and brain damages [3, 4].

Olanzapine long-acting injection (LAI) is a pamoate monohydrate salt of olanzapine that is administered by deep intramuscular gluteal injection. The efficacy and tolerability profile of olanzapine LAI is similar to that of oral olanzapine [5, 6]. The “post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome” (PDSS) was the “scariest” side effect despite its low incidence (approximately 0.07% of injections) [7]. The major reason for non-acceptance of olanzapine pamoate treatment was the protocol of administration. The recommendation was that the injection had to be administered by qualified personnel in a medical setting. After the administration, the patients had to remain under observation for 3 h and then they could only leave the hospital if accompanied by another person [8]. These measures generated higher costs for the hospitals (treatment room arrangement, monitoring room, etc.) but were balanced by the better cost-effectiveness ratio of LAI compared with OA [9].

However, patients on LAI treatment had the longest period of remission of the disease and some of the best adherences to treatment [10]. Its efficacy has been reported even in preventing relapses in the catatonic form of schizophrenia [11].

Despite its proven effectiveness, high cost, stigma, and fear determined a world-wide underuse of LAIs [12]. The patient’s refusal of injectable treatment is related to the administration mode, the treatment control, the administration protocols (in hospitals or in specialized healthcare centers, post-injection monitoring in the case of olanzapine pamoate, etc.) [13].

To all of the above, the COVID-19 pandemic added new restrictions or limitations in prescribing and administration of LAIs [14, 15]. The aim of this paper was to present the outcomes after an abrupt and unplanned switch from olanzapine long-acting injection (OLZ-LAI) to oral olanzapine (O-OLZ). The Hospital Ethics’ Committee entitled “Comisia de Etică” approved this research.

Methods

27 patients treated with OLZ-LAI were recorded in March 2020 in the documents of the Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry and Neurology of Brasov, Romania, an academic emergency psychiatric unit with 3 departments and 150 beds. In order to limit the possibility of contamination, after the State of Emergency was declared in Romania (March 15, 2020), the authorities have recommended limited or restricted access to hospitals, which remain strictly intended for emergencies alone.

As a result, the public compartment for the administration of LAIs (including olanzapine pamoate) was closed. Given that, schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine LAI were advised to continue the administration in another setting (e.g. private clinics). Due to high costs (around 30 euro/injection), working schedule in the private practices, the long distance from home, and anxiety generated by the new situation, 21 schizophrenia patients preferred to be switched from OLZ-LAI to oral olanzapine. Only 6 patients continued the treatment with the long-acting formulation. They agreed to participate in this observational study and provided signed informed consent.

21 patients started oral olanzapine treatment 30 days after the last OLZ-LAI administration according to the following model:

-

2 × 210 mg injections/month were replaced with 15 mg oral olanzapine/day

-

1 × 300 mg injection/month was replaced with 10 mg oral olanzapine/day

-

2 × 300 mg injections/month were replaced with 20 mg oral olanzapine /day

-

1 × 405 mg injection/month was replaced with 15 mg oral olanzapine/day

We compared the patients’ outcomes in both groups: Switched from OLZ-LAI vs. Stay on OLZ-LAI.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, clinical and olanzapine-related characteristics of patients treated with OLZ-LAI and O- OLZ were calculated using basic statistic. Variables scores before and after OLZ-LAI exposure were compared using the variance ratio test (F-test). Statistical significance was set at two-sided p < 0.05.

Results

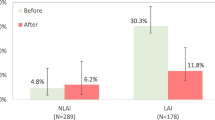

The results showed that those who switched from LAI to the oral form of olanzapine relapsed more frequently (15 out of 21 vs. 1 out of 6). For a clearer image of the two groups, we also presented also the data of the 27 subjects before the COVID-19 period. The demographics and clinical characteristics of patients switched to oral olanzapine are presented in Table 1.

The main reason for the initiation of olanzapine pamoate was non-adherence to oral medication (80.95%), which is similar to the findings of previous studies [16]. The mean age of starting LAI olanzapine was 36.42 years (SD ± 10.09), similar to the mean age of patients in de Haya et al. study [17].

The longest treatment with olanzapine LAI was 9 years and the mean duration of olanzapine LAI treatment was 6.09 years (SD ± 1.51). There was a significant difference in the number of episodes before and after olanzapine LAI initiation (5.38 vs. 0.57, p < 0.0001). The most used dosage was 300 mg every 2 weeks and the most unchanged dose in time was 300 mg every 4 weeks. During the treatment period, the LAI group received more than 1000 injections with only 7 mild intensity PDSS (sedation, confusion, slurred speech), all fully recovered, and all but one patient continued the treatment after the event.

The outcomes of the patients that were switched from OLZ-LAI to oral olanzapine were not favorable (Fig. 1). In the next 6 months, 15 patients (71.4%) relapsed, 12 (66.7%) needing hospitalization. Of these, 2 patients resumed treatment with OLZ-LAI, 3 were switched to another type of LAI (2 on aripiprazole and 1 on paliperidone). There was no statistically significant difference in the doses administered to those who relapsed compared to the 6 who did not relapse (361.1 mg ± 102.4 vs. 417.5 mg ± 134.9, p = 0.275).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first naturalistic study regarding the switch from olanzapine long-acting to oral olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia in clinical remission. Given the long period of remission before the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the patients were considered recovered (remission of symptoms, good level of functioning). They managed to have stable life partners and worked. Some even have children to take care of. The biggest problem in the pandemic was the OLZ-LAI 3-h surveillance model. During the COVID-19 pandemic this was not possible and clinicians refused to risk and to indicate administration at home, or with a shorter interval of monitoring (as the majority of reactions have been reported within the first hour after the injection) [18].

The switch to oral treatment, initially considered temporary (no one knew in March 2020 how long the pandemic will last), has shown that patients can become non-adherent again in an active (no longer want treatment) or passive (forget to take treatment) manner. This event led to relapse in over 70% of the patients. On the other hand, 5 out of 6 patients (83.33%) who continued with LAI remained in remission.

Olanzapine LAI provides a slow continuous release of olanzapine that continues for approximately six to eight months after the last injection (https://oxfordhealthbrc.nihr.ac.uk/our-work/oxppl/table-4-lai/). According to the experts’ recommendation we started with oral olanzapine when the next injection is due, with careful monitoring especially in the first two months after the discontinuation of olanzapine LAI. The patients started to relapse as seen in Fig. 1.

As far as we know, such studies are not published. In practice, LAIs are stopped for the main following reasons: i) switching from a first-generation LAI to a second-generation LAI; ii) patients no longer want to continue; iii) there is no evidence of efficacy [19].

The study’s limitation is the small sample size. The strength of the report lies in the patient’s characteristics (remission and long period of olanzapine LAI treatment) and the long follow-up period.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought multiple disservices to the current medical practice. One of these was the visible decrease in the initiations of OLZ-LAI and even the cessation of administration due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic. Under these circumstances, even patients with long periods of remission relapsed after switching to oral treatment. It would seem that the previous duration of remission is not a protective factor when the patient becomes non-compliant with treatment again.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

with the authorization of the hospital Ethics Committee.

Abbreviations

- LAI:

-

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics

- OLZ-LAI:

-

Olanzapine long-acting injection

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease-19

- OA:

-

oral antipsychotic

- PDSS:

-

post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome

- O-OLZ:

-

oral olanzapine

- SD:

-

standard deviation

References

Kane JM. Review of treatments that can ameliorate non-adherence in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 5):9–14.

Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, et al. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia – a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127:83–92.

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World Federation of Societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14:2–44.

Stahl SM. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: shall the last be first? CNS Spectr. 2014;19(1):3–5.

Detke HC, Zhao F, Witte MM. Efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia: an insight from effect size comparison with historical oral data. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-51.

Kane JM, Detke HC, Naber D, et al. Olanzapine long-acting injection: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind trial of maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:181–9.

European Medicines Agency: Assessment report for Zypadhera. 2008, Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/Zypadhera/H-890-en6.pdf. Accesed 28 May 2020.

Electronic Medicines Compendium: Summary of product characteristics for ZYPADHERA 210 mg, 300 mg, and 405 mg, powder and solvent for prolonged release suspension for injection. 2009. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21361/S. Accesed 28 May 2020.

Furiak NM, Ascher-Svanum H, Klein RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of olanzapine long-acting injection in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia in the United States: a micro-simulation economic decision model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(4):713–30.

McDonnell DP, Landry J, Detke HC. Long-term safety and efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 6-year, multinational, single-arm, open-label stud. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):322–31.

Ifteni PI, Teodorescu A. Prevention of catatonia with olanzapine long-acting injectable. Am J Ther. 2017;24(5):e599–601.

Taylor DM, Velaga S, Werneke U. Reducing the stigma of long acting injectable antipsychotics - current concepts and future developments. Nord J Psychiatry 2018;72 (sup1): S36-S39.

Yeo PJI, Jang JM, et al. Acceptance rate of long-acting injection after short information: a survey in patients with first- and multiple-episode psychoses and their caregivers. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;11(6):509–16.

Ifteni P, Dima L, Teodorescu A. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics treatment during COVID-19 pandemic - A new challenge. Schizophr Res. 2020;S0920–9964(20)30237–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.030.

Gannon JM, Conlogue J, Sherwood R, et al. Long acting injectable antipsychotic medications: Ensuring care continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Schizophr Res. 2020;S0920–9964(20)30253-X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.001.

Law MR, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS. A longitudinal study of medication nonadherence and hospitalization risk in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0107.

Ascher-Svanum H. William S Montgomery, David P McDonnell, et al. treatment-completion rates with olanzapine long-acting injection versus risperidone long-acting injection in a 12-month, open-label treatment of schizophrenia: indirect, exploratory comparisons. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:391–8.

Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: what, when, and how. CNS Spectr. 2021;15:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852921000249.

Keks N, Schwartz D, Hope J. Stopping and switching antipsychotic drugs. Aust Prescr. 2019;42:152–7.

Funding

Researchers own work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAA, TA and PSP conceived the study; ICA and DL performed the statistical analyses; TA, IP, MAA and DL wrote the paper; and all authors were involved in the writing and critical appraisal of methods and approved the final.

manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of.

the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

or comparable ethical standards.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This research present results of the switch from olanzapine long-acting injectable to its oral equivalent during covid-19 pandemic.

Informed Consent

The written informed consent for this research was obtain from all patients at admission.

Consent for Publication

All subjects provided informed consent for publication.

Conflict of Interest

In the last 3 years, TA and IP have received honoraria for consulting or lectures from Lundbeck, Janssen and.

Angelini.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miron, AA., Teodorescu, A., Ifteni, P. et al. Switch from Olanzapine Long-Acting Injectable to its Oral Equivalent during COVID-19 Pandemic: a Real World Observational Study. Psychiatr Q 93, 627–635 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-021-09924-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-021-09924-9