Abstract

This paper focuses on the consequences of the implementation of a bilateral agreement between Israel and Thailand for migrant workers in the agricultural sector. Its purpose is to shed light on the key mechanisms of the transition from the marketization to demarketization of recruiting migrant workers, and to show how this transition affects the forms of labor recruitment and its consequences for the labor migrants. The study is based on three face-to-face surveys conducted among 180 agricultural workers from Thailand. Fifty-five were surveyed in 2011 before the implementation of the bilateral agreement, and 125 were interviewed after the agreement was implemented. Relying on a “before” and “after design, we first highlight the ways in which the private recruitment industry operated in Israel in the context of a state-sponsored temporary labor migration program, identifying the actors involved in the process and explaining how they profited from the labor recruitment. Second, we shed light on the importance of bilateral agreements in eliminating illicit practices for recruiting foreign workers in Israel and its practical consequences for the Thai migrants arriving under the new arrangement. We discuss our findings in light of the theories presented in the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Labor migration is on the rise in a number of receiving countries in North America, Western Europe, Asia, and the Middle East (Castles, 2006; Weiler et al., 2020). Responding to the increasing demand for low-skilled workers in the secondary sectors of host societies’ economies, millions of people cross borders to find better economic opportunities. In 2021, the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimated the number of international migrants at 272 million, of whom 169 million, about 62%, were migrant workers. Migrant workers accounted for approximately 4.9% of the labor force in the receiving countries (ILO, 2021).

The formats for recruiting migrant workers for host societies have changed over time, shifting from a predominantly state-driven system through bilateral agreements to a largely market-driven system dominated by private recruitment and manpower agencies. The 1950s and the 1960s were the height of bilateral labor agreements when official employment services in Western countries played a major role in the recruitment of foreign workers. After the global economic crisis in the 1970s, many countries placed restrictions on migratory flows, gradually reducing the signing of bilateral agreements. However, there was also the concomitant development of a market-driven system of recruitment (Wickramasekara, 2012; Chilton & Woda, 2022).

This new trend has led to the emergence of the “migration industry,” which consists of private actors such as recruitment and manpower agencies, informal brokers, and employers who profit from the commodification of labor migration (Salt & Stein, 1997; Hernandez-Leon, 2005, Hernández-León, 2013, Gammeltoft-Hansen & Sorensen, 2013). The development of the migration industry has caused the cost of migration to escalate, leaving migrants vulnerable to exploitation and abuse of their rights by the intermediaries on whom they depend to get a job in the destination country (see e.g., Agunias, 2009; Fernandez, 2013; Xiang & Lindquist, 2014; Groutsis et al., 2015; Anderson & Franck, 2017; Kushnirovich, Raijman & Barak-Bianco, 2019).

Since the 1990s, we have witnessed a significant increase in the number of countries engaging in bilateral agreements (hereafter BLAs) and a new peak in the number of agreements signed per year (Chilton & Woda, 2022; Livnat & Shamir, 2022). Bilateral labor agreements are usually developed in response to labor shortages. Their goals are regulating migratory flows, fighting illicit employment, protecting the rights of employees, reducing unemployment in the countries of origin, making labor mobility easier, and selecting migrant temporary workers based on labor market demands. Bilateral agreements may encompass the involvement not only of employers, migrant laborers, and government agencies but also a growing number of private and nongovernmental organizations (Bobeva & Garson, 2004; Cholewinski, 2015; Pittman, 2016). Sometimes BLAs cover only certain sectors of the economy in the host country such as construction or agriculture. Even within a specific sector, only migrants from specific countries are covered. Thus, in many countries both market and non-market (public) forms of recruitment coexist.

In this paper, we focus on the recruitment of labor migrants from Thailand who have been officially hired to work in the agricultural sector in Israel since the 1990s. From the beginning, the state delegated the recruitment of migrants to private agencies, which over time became part of a well-developed migration industry characterized by fraud and abuse of prospective migrant workers (Raijman & Kushnirovich, 2012; Kemp & Raijman, 2014). However, in 2012, the recruitment process switched to a public non-market system when the first bilateral agreement was signed between Israel and Thailand (signed in 2011 and implemented in 2012). It was followed by the signing of bilateral agreements with other countries.Footnote 1 Thus, labor migration to the agriculture sector in Israel is an interesting case study for probing the positive consequences of switching from the marketization to the demarketization of migrant labor recruitment.

This study contributes to the literature by providing several valuable insights into the intricate mechanisms involved in the transition from marketization to demarketization in the recruitment of temporary migrant workers in agriculture. First, we highlight the ways in which the private recruitment industry operated in Israel in the context of a state-sponsored temporary labor migration program in the agricultural sector, identifying the actors involved and explaining the ways by which they profited from labor recruitment. Second, we shed light on the importance of bilateral agreements in eliminating illicit practices in the process of labor recruitment and promoting fairer recruitment procedures. Finally, we explain how the transition from marketization to demarketization affects the situation of Thai migrants who come to Israel to work in the agriculture sector under the new arrangement.

There is a vast literature from international organizations such as the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) dealing with bilateral and multilateral labor agreements (see e.g., Bobeva & Garson, 2004; Battistella & Khadria, 2011; Wickramasekara, 2012; Pittman, 2016; Livnat, 2019). However, until recently there has been little investigation into how these agreements impact illegal recruitment practices and their potential to improve the vulnerable position of migrants in the host country’s labor market (Chilton & Wada, 2022; Livnat & Shamir, 2022). One reason for the limited research is the lack of appropriate data to measure the effects of the new regulations on recruitment outcomes. In this paper we aim to fill this gap in the literature by using a unique data set collected before and after the implementation of a bilateral agreement between Thailand and Israel regarding the recruitment of Thai workers for the Israeli agricultural sector. Using this approach, we can assess the extent of the impact of the agreement on the recruitment process. This study not only enriches the existing literature on labor migration but also provides practical insights into creating more ethical and efficient labor recruitment systems. The findings are relevant not only to Israel but also to other countries facing similar challenges in managing temporary migrant workers.

We begin by presenting a description of labor migration to Israel in general and to the agriculture sector in particular, followed by the study’s theoretical background. After describing the methodology of the research, we present the findings and discuss them in light of the theories in the literature.

Labor Migration in Israel

The catalyst for the beginning of the massive recruitment of overseas labor migration to Israel in the 1990s was the first Intifada (the 1987 Palestinian uprising), which worsened the political and security conditions in the country. The systematic border closure imposed by the Israeli government to deal with the terrorist attacks resulted in a serious labor shortage in the agricultural and construction industries where Palestinian workers were employed after the 1967 Six-Day War. The increasing demand of employers for cheap labor to replace the Palestinian workers was the main engine driving the massive official recruitment of overseas labor migrants since 1993 (Raijman & Kemp, 2007).

Labor migration in Israel is temporary in nature and based on contractual labor, with no path to permanent settlement or citizenship. Work permits are granted to employers, not to the migrants, thereby maximizing the control of both the employers and the state over the labor migrants. Migrant workers may stay and work in Israel for only up to 63 months. The state does not allow residence without a work permit and imposes a strict deportation policy permitting the arrest and expulsion of undocumented migrants at any time by a simple administrative decree.

According to Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority (PIBA, 2022), the total number of temporary migrant workers in Israel as of the end of 2021 was 123,214. Only 16% of them were residing in the country without a work permit (PIBA, 2022). 60% of the migrants were employed in the caregiving sector (mainly from the Philippines, India, Sri-Lanka and Nepal), whereas construction workers (mainly from China, Ukraine, and Moldova) and agriculture workers (from Thailand) comprised 13% and 24%, respectively. Thus, Thai agriculture workers were the second largest group of temporary migrant workers in Israel.

From the outset, the official recruitment of foreign workers in Israel in the three sectors– agriculture, construction and caregiving–was entirely privatized and conducted through recruiting agencies in Israel and in the countries of origin. These agencies charged exorbitant and illegal fees to come to work in Israel. Israeli governments have been reluctant to sign bilateral agreements with the countries of origin to regulate recruitment and employment conditions, thereby enabling profit-seeking private agents to dominate this field (Kushnirovich, 2010; Kemp & Raijman, 2014). However, a turning point regarding labor migration recruitment practices occurred in 2012 with the implementation of the first bilateral agreement signed with the government of Thailand (in 2010) for the recruitment of migrants in the agricultural sector.

Labor Migration from Thailand

For more than two decades Israel has been one of the most popular destinations for Thai labor migrants in the Middle East (Rainwater & Williams, 2019). Since the beginning of the formal recruitment in the agricultural sector, the state granted the Moshavim Movement (the non-profit organization that represents the diverse interests of agricultural cooperatives in Israel) a quasi-monopoly over the field of recruitment (Cohen, 1999 Kurlander, 2022). At this stage, recruitment fees were prohibited altogether.Footnote 2 The Moshavim Movement maintained its near-exclusive control over the migrant labor market in the agricultural industry up until 1998, when private recruitment companies who wanted to benefit from recruiting Thai workers pressured the government to open the recruitment market to other companies in Israel.Footnote 3

The entry of many new private recruitment agencies in 1998 led to growing attempts to reap the benefits from the mediation fees. Although the state granted work permits to the employers, they were obliged by law to ask local recruitment agencies to recruit the labor migrants for them. These local agencies contacted private companies in Thailand that took care of the actual recruitment of the migrants. Up until 2006 there were rules prohibiting agencies from charging workers recruitment fees. However, the majority of the profits made by the recruitment agencies came from fees paid by the labor migrants. In an effort to curb this malpractice, in 2006 new regulations permitted agencies to charge workers a fee of no more than NIS 3,479 (about $1,000; this amount is revised annually) (Employment Service Regulations, 2006). Nevertheless, in reality, recruitment agencies charged migrants significantly higher commissions, amounting to thousands of US dollars (State Comptroller’s Report, 2010).

In July 2005, the government announced that, to put an end to the corrupt practices of the private agencies, the recruitment of migrant workers would be conducted solely under the supervision of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or another public organization (Israel Government, 2005, Government Decision #4024). Despite the government decision, the implementation of the BLA in the agriculture sector was repeatedly postponed mainly due to the political pressure exerted by the employers and private recruitment agencies in the agricultural lobbying sector in Israel because they did not want to give up their lucrative profits (Kemp & Raijman, 2014). In Thailand, the period before the signing of the BLA was a time of political instability, and frequent changes in the government postponed their signing (Kurlander, 2019).

However, there were also demands, both at the international and the local level, to sign the BLA with Thailand. First, in 2003 the US State Department published the annual Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP) in which Israel was listed in Tier 2. This ranking prompted the desire to intensify the fight against the manpower and brokerage firms involved in labor trafficking activities. Second, non-governmental human rights organizations (NGOs) were gaining strength. They opposed the labor migration policy in Israel, and demanded that it sign bilateral agreements with countries sending workers to Israel to avoid illicit activities in the process of their recruitment (Kemp & Raijman, 2014).

The bilateral agreement with Thailand was signed in 2010 and implemented in 2012 by the Population and Immigration Authority in Israel (PIBA) and the Thai Ministry of Labor. The governmental agencies were assisted by two non-profit organizations: IOM (International Organization for Migration) in Thailand and the Center for International Migration and Integration (CIMI) in Israel.Footnote 4 The Israeli government is responsible for the management of the labor migration scheme, while the Thai government and the IOM undertake the recruitment and selection of the candidates and their transportation to Israel. Prospective Thai migrants interested in coming to work in Israel contact the Department of Employment at the Ministry of Labour (Thailand) or the Thailand-Israel Cooperation on the Placement of Workers (TIC). They fill out forms and undergo medical exams. To prevent corruption, migrants are selected through a computerized lottery, so that no one could assure the registered participants a work permit. Most importantly, the bilateral agreement eliminated the role of private agencies and their brokers in the recruitment process.Footnote 5 The agreement contained a general clause regarding the “promotion of the protection of rights of Thai nationals throughout the process of recruitment and employment” (THA Labor, 2020). While the agreement provided specific mechanisms to enforce and ensure a “legal, fair and well-informed recruitment process,” it did not make any specific provisions for the protection of the migrants’ rights (Livnat, 2019; Cohen & Kurlander, 2023). Given this limitation, we focus only on the impact of the BLA on the recruitment practices of Thai migrant workers.

Theoretical Background

Receiving states deal with issues of labor recruitment and management. They usually set the conditions for other non-state actors (for-profit and non-profit) to be a part of the process. To understand the forms by which receiving states engage with non-state actors to facilitate cross-border mobility, Surak (2018:5) proposed a typology based on two key components involved in the relationship between the state and the actors in charge of the recruitment: (a) the type of actor (private or civic/public) and (b) the nature of the delegation (formal or informal). The four outcomes of the typology are: (1) the state officially outsources responsibility to for-profit agents (private companies); (2) the state, de facto, delegates responsibility to for-profit actors; (3) the state officially outsources responsibility to non-profit actors; (4) the state, de facto, delegates responsibility to non-profit actors. The first two categories represent market-managed systems that develop into migration industries, whereas the last two categories represent non-market systems in which the state retains control over the recruitment process and delegates some functions of the recruitment process to non-profit actors.Footnote 6

It is important to note that market and non-market forms of state delegation can vary within countries according to the sectors of employment and types of labor migrants working within the same sector of employment (Surak, 2018:28). Furthermore, market and non-market forms of the delegation are not static but can change over time due to economic and political reasons. Thus, for example, private systems of labor migrants’ recruitment can switch to public managed systems (e.g., South Korea, see Surak, 2018: 27–28; in Israel, see Kushnirovich & Raijman, 2022). Changes might also occur in the opposite direction: from delegation to non-profit agents and public institutions to the privatization of the recruitment (e.g., South Africa’s guest-worker program for miners and the Bracero Program in the US (Surak, 2018:27–28).

Market Delegation of Labor Migration Recruitment: The Emergence of the Migration Industry

The development of a migration industry in recruitment is part of a much larger trend toward the outsourcing of state operations representing the marketization process. Marketization, usually referred to as “commercialization and/or commodification, is a process through which the market sphere continually penetrates and slowly displaces non-market activities” (Vujnovic, 2012: 160). The emergence of private labor migration recruitment in the form of a migration industry is a result of such marketization in which migrants’ labor is regarded as a commodity (Burawoy, 2010).

The migration industry is defined as “the ensemble of entrepreneurs, firms, and services which, chiefly motivated by financial gains, facilitate international mobility, settlement and adaptation, as well as communication and resource transfers of migrants and their families across borders” (Hernandez-Leon, 2005: 26, Hernández-León, 2013, Gammeltoft-Hansen & Sorensen, 2013). Restrictive immigration policies and neo-liberal configurations of migration governance usually lead to the involvement and empowerment of formal and informal market actors (mainly private companies, sub-agents, and employers) in the recruitment and management of migration flows (Menz, 2013; Kemp & Raijman, 2014; Hoang, 2017; Surak, 2018).

At the start of the marketization process, state regulations establish the recruitment mechanisms for the private companies operating on its behalf. However, over time a conflict of interests may develop as regulatory and commercial structures compete to protect their respective primary interests: “order for the former and profit for the latter” (Xiang & Lindquist, 2014:16). To maximize economic gains, legal private agencies may sometimes adopt illicit ways of operating such as charging illegal fees or using informal recruiters operating in both the sending and destination countries (Fernandez, 2013). Thus, recruitment practices frequently take place in a hazy normative space where clear-cut distinctions between (il)legal and il(licit) are impossible to achieve (Lindquist, 2010; Kemp & Raijman, 2014). As a result, regulatory frameworks are not always able to achieve their goals of controlling the commercial actors who engage in illicit practices to recruit labor migrants.Footnote 7

To investigate how state and commercial actors interact in the emergence and reproduction of the migration industry, we rely on the decentered approach to regulation (Black, 2002), which posits that regulation occurs not only within the state but also through interdependencies with other non-state actors. Based on this approach, Fernandez (2013) proposed five core concepts for analyzing the relationships between state and non-state actors in the process of recruitment: (1) complexity, (2) fragmentation, (3) interdependencies, (4) ungovernability, and (5) the rejection of a clear distinction between public and private.

Complexity refers to the multiplicity of parties involved in the management of the recruitment of labor migrants. State delegation to private actors (employers and manpower agencies, and informal intermediaries) created a complex, multifaceted policy environment in which the actors may have different and even contradictory goals. They also vary in the power they have, but they all function in an environment of uncertainty (Menz, 2013; Xiang & Lindquist, 2014; Anderson & Franck, 2017; Anderson, 2019).

The complexity and multiplicity of social actors involved in the recruitment process result in the fragmentation of knowledge or information and power, which are dispersed among the social actors involved in the recruitment of labor migrants. There is an asymmetry of knowledge about job opportunities and work conditions in the host country. Indeed, the private actors manage access to this information as a means of exercising power over the migrant workers (Mieres, 2014). The asymmetry of knowledge also creates asymmetrical power between the private agencies and prospective migrants, as the former act as “gatekeepers who decide who and under what conditions migrants may obtain working abroad” (Pittman, 2016: 270). The lack of transparent information pushes prospective migrants to rely on private intermediaries to navigate the complex bureaucracy of the recruitment process and to pay exorbitant amounts of money to get a work permit (Lindquist, 2010: 132; Anderson, 2019).Footnote 8

Fragmentation of power and control is in turn related to the autonomy and ungovernability of the actors involved in the process of recruitment. Although regulations try to manage and control the behavior of all parties involved, their effects depend on the relative power of the various actors, how susceptible they are to regulatory intervention, and how compliant they are with the law (Fernandez, 2013: 816). Furthermore, given that interactions and interdependencies between the different private actors such as the recruiting agencies in the countries of origin and countries of destination may extend beyond national borders, it becomes difficult for the receiving state to enforce rules or to prosecute fraud that takes place outside its borders (Pittman, 2016; Anderson & Franck, 2017). Thus, the recruitment practices of state-managed temporary work programs under the auspices of commercial actors often take place in a blurry normative space where clear distinctions between the public/private and legal/illegal disappear (Kemp & Raijman, 2014).

The consequences of ungovernability are critical for labor migrants. By demanding high (and illegal) recruitment fees from the migrants, the cost of migration is shifted to the migrants and their families, negatively affecting not only their earnings and remitting power but also their already precarious employment status in the host country (Bélanger, 2014; Malit & Naufal, 2016; Platt et al., 2017; Shamir, 2017; Cruz-Del Rosario & Rigg, 2019). The need to repay the money invested in migration may prevent migrant workers from claiming their rights in the host society’s labor market because they are afraid of losing their jobs. Consequently, migrant workers become more vulnerable to exploitation (Tierney, 2011; Kushnirovich, 2012; Bélanger, 2014; Kemp & Raijman, 2014; Basok & López-Sala, 2016).

Non-market Delegation of Recruitment

As noted earlier, market and non-market forms of the delegation of recruitment can change over time due to economic and political reasons. Marketization may be reversed and switch from private forms of recruitment to a publicly managed system of labor migration. The process of shifting activity from the market to the non-market public sector is called demarketization (Glyn, 1989). It involves the de-commodification of excessively marketized spheres (Burawoy, 2010; Shachar, 2018). We use the term demarketization to define a situation in which the deliberate decisions of the state lead to the transition of the management of labor migration recruitment from the private to the public sector (Surak, 2018).

A legal tool that has proliferated in recent decades to enable collaboration between countries in the recruitment of temporary labor migration is the bilateral labor agreement (Chilton & Posner, 2018; Livnat & Shamir, 2022). Such agreements manage and regulate the flow of labor migration between countries (Chilton & Woda, 2022: Cholewinski, 2015) and have been recognized as a good practice in the governance of labor migration flows (Pittman, 2016; Wickramasekara, 2015). Usually, BLAs establish a government-to-government recruitment mechanism by eliminating the role of commercial actors in order “to gain control over migrants and the migration industry” (Livnat & Sahmir, 2022:67). BLAs can improve the governance of labor migration by defining the responsibilities of the sending and receiving countries, specifying the agents for recruitment in both countries, increasing the transparency of the recruitment process by providing relevant information to the migrants (contracts, labor laws), preventing recruitment malpractice, controlling the costs of migration and recruitment fees, mobilizing workers through legal channels, and monitoring employment practices in the host labor market by sharing responsibilities between the country of origin and the host country (Battistella & Khadria, 2011; Livnat, 2019; Livnat & Shamir, 2022).

Note that although regulations related to the recruitment process are clearly stated and implemented, provisions for the protection of migrant workers’ rights are less common. Some have argued that sometimes the sending countries agree to forgo the protection of migrants’ rights in the agreements for the sake of the country’s interest to increase migration and the related remittances associated with it (Livnat & Shamir, 2022:83). Over time, the share of BLAs addressing provisions for migrant workers’ rights has declined (Chilton & Woda, 2022). Furthermore, even if they contain a general statement about the equal treatment of labor migrants, they usually do not provide specific mechanisms to ensure its compliance (Livnat & Shamir, 2022:81).

In general, scholars have overlooked the effects of switching between market and non-market forms of recruiting temporary labor migrants through bilateral agreements. Very little research (Chilton & Wada, 2022; Kurlander & Cohen, 2022; Livnat & Shamir, 2022) has explored whether the implementation of BLAs is an adequate framework for ensuring fair, legal labor recruitment, eliminating illegal practices, and improving the precarious position of migrants during the recruitment process. To fill this gap in the literature, we conducted a study of the consequences of the implementation of a bilateral agreement between Israel and Thailand for migrant workers in the agricultural sector. Its purpose was to explain the key mechanism of the transition from the marketization to the demarketization of the recruitment of temporary migrant workers. In addition, we showed how the shift from the delegation of the recruitment from the market to non-market institutions affected the forms of labor recruitment as well as its consequences for the labor migrants.

Methodology

The study is based on three surveys conducted in Israel among 180 agricultural workers from Thailand who had a work permit at the time of the survey. Fifty-five were surveyed in 2011 before the implementation of the BLA, and 125 were interviewed after the agreement was implemented: 50 workers were interviewed in 2014, 25 in 2016, and 50 in 2017. The “before” and “after” design allowed us to assess the effectiveness of the BLA in eliminating malpractice in the recruitment process.

Data were collected through a face-to-face survey that included questions about demographic characteristics, pre-migration background, motives for migration, reasons for choosing Israel as a destination, the migration process, the actors involved in recruitment, recruitment fees, and sources of funding, and employment and living conditions.

Gathering data from migrant workers is inherently challenging because it is impossible to create a representative sample; therefore, we combined convenient and snowball samples. In addition, to ensure the sample’s representativeness, quotas for geographical location were imposed, so that Thai workers from all geographical areas (North, South, Center, and Jerusalem) were included. Each respondent was asked to suggest names and phone numbers of their Thai friends and acquaintances working in Israel. Some migrants were approached through internet groups of migrants from Thailand in Israel (WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.). No more than 3 interviews at one workplace were conducted. Surveys were anonymous and were conducted in Thai by interviewers fluent in the language.

Table 1 lists the socio-demographic characteristics of the migrants in the sample. The majority of respondents were young men (on average 32–33 years old) with relatively low levels of education (10 years of schooling). Most of them (over 90%) were employed before leaving Thailand and earned an average monthly income of about $360 per month. These reported levels of income are far below their possible wages in Israel, where migrant workers in agriculture might anticipate seeing triple the income ($1,365 on average). The income disparity is a powerful magnet that attracts workers to Israel. It explains why migrants are willing to uproot from their families, face significant material and emotional hardships, and take on hard work in the agricultural sector of the Israeli labor market.

Findings

Evaluating the Impact of the Bilateral Agreement

To evaluate how the implementation of the bilateral agreement changed the process of recruitment, we organize our analysis along four main themes. The first describes how the agreement changed the complexity of the recruitment infrastructure and led to its flattening. The second-dimension centers on the switch from fragmentation to the transparency of knowledge. The third dimension focuses on the switch from the ungovernability of the private actors and institutions involved in the recruitment process to the governability and control of the process. The fourth dimension summarizes the consequences of the implementation of the bilateral agreement for migrant workers.

From the Complexity of the Infrastructure of the Recruitment to its Flattening

To identify all actors involved in the recruitment process before and after the BLA, we asked our respondents whether anyone contacted them to offer a job, who took care of the recruitment process, and the fees paid by the migrants. Our findings reveal that before the bilateral agreement’s implementation, the process of recruiting Thai workers to Israel involved several intermediaries in Israel and Thailand such as recruitment agencies, formal and informal brokers, migrants’ social networks, and employers. This multiplicity of actors illustrates the complexity involved in the recruitment process.Footnote 9

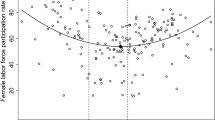

We identified three main recruitment patterns (see Table 2; Fig. 1). The first form of recruitment was through the active recruitment of agencies and their sub-agents (brokers) in Thailand. About 44% of our interviewees reported using this form. Although most local recruiting firms had their headquarters in Bangkok, the country’s capital, local firms relied on the services of unofficial sub-agents or brokers to reach prospective migrants in peripheral areas. These brokers were usually former Thai migrants in Israel who demand a mediation fee for their services in addition to the recruitment fees paid to the recruiting agency. Thai migrants’ perceptions about the difficulty and complexity of the regulations were an incentive for them to seek the services of brokers to navigate the complex bureaucracy of getting a work permit for the agricultural sector in Israel.Footnote 10

The second form of recruitment involved social networks, both in Israel and Thailand, which directed potential candidates to the recruitment agencies to begin the process of applying for a job in Israel. About one-third of the Thai migrants reported using this form. In this way, friends and family assisted prospective migrants in recommending the agencies to apply to when they came to Israel. Sometimes, these recommenders were working covertly as agents of the recruitment firms.

The third form of recruitment was through Israeli agricultural employers who sought employees through ethnic networks of migrant workers. About 20% of our participants reported using this form. This type of recruitment typically started when: (1) a potential immigrant asked friends in Israel to speak with their employer on their behalf; or (2) a migrant who was already in Israel was asked by his/her employer to get in touch with a friend and offer them the chance to come to Israel and work for the same employer.Footnote 11 In any case, the prospective migrant had to apply for a visa through the recruitment agency in Thailand, and had to pay the recruitment fees. Given that hiring new employees who are friends or relatives of current employees made it easier for the employers to manage the social dynamics of the workplace, many Israeli companies in the agricultural industry appeared to prefer this method of recruitment. Migrant workers also preferred this form of recruitment because it reduced uncertainty about their prospective employer and the work and living conditions. In sum, the three forms of recruitment underscore the multiplicity of commercial actors (social networks, employers, private agencies and sub-agents/brokers) operating in the migration industry. The number of players created a very complex social infrastructure, which changed with the implementation of the BLA.

The data in Table 2 show that, since 2012, all Thai migrants arriving in Israel arranged their trip to Israel through government offices such as local labor offices in their provinces, the Thai Ministry of Labor, and the IOM (see pattern 4 in Fig. 1). Private agencies and their brokers both in Israel and Thailand were completely eliminated from the recruitment process.Footnote 12 The Israeli agencies are now responsible for the workers after they arrive, a service for which they are allowed to charge a fee fixed by government authorities. Currently, it is $1,113 (Employment Service Regulations, 2006).Footnote 13 Thus, the implementation of the BLA dramatically reduced the complexity of the system and flattened the recruitment infrastructure by changing the number and types of actors involved in the process: it switched from a business-to-business model to a government-to-government model (Livnat & Shamir, 2022: 87).

From Fragmentation to Transparency of Knowledge

Another way to assess the impact of the BLA on the recruitment process is to look into the methods through which prospective Thai migrant workers learned about work opportunities in Israel before and after the implementation of the bilateral agreement (see Table 2). Before the BLA, migrants gathered information mainly from social networks (82.3%) and private agencies (14.6%). This asymmetry in relevant knowledge made the migrants completely dependent on social networks and recruitment companies for information about coming to Israel to work and reflected the fragmentation of the information.

After the BLA was implemented, the first step was to ensure that Thai workers received extensive public information about how to apply for employment in Israel, providing clear information about the costs of moving, wages, working conditions, and so forth. This stage is important to make the process transparent and to provide information for all those interested in coming to work in Israel, not just to the manpower companies and brokers as it was before the BLA.

The new forms of providing relevant information to potential migrants implemented by the BLA have markedly changed the typical ways of learning about job opportunities. The proportion of migrant workers who learned about job openings through the media—including radio, television, newspapers, and official bulletin boards—increased from 3.1 to 34.7%. In addition, 17% of the respondents said they had learned about job openings in Israel from government offices in their home countries —in contrast to none before the bilateral agreement’s implementation. Furthermore, before departure, workers receive a comprehensive orientation to inform them about their rights and obligations as well as general information about Israeli culture and society. Attendance at this orientation day is compulsory, because at this orientation the worker receives a contract signed by his/her future employer.Footnote 14

These results suggest that the new arrangements resulted in making the recruiting process more transparent. Information regarding jobs, maximum fees, and steps for the selection of workers was shared through the media and public actors, not only social networks and private recruitment agencies (and their sub-contractors) who controlled the information before the BLA. These changes in the diffusion of relevant knowledge to the migrant workers helped reduce the fragmentation of knowledge and power prevalent before the BLA.

From Ungovernability to Governability

The state’s delegation of the recruitment to private agencies in 1998 led to growing attempts to reap the benefits from the mediation fees. Since the beginning of the recruitment of Thai workers, there were rules prohibiting agencies from collecting recruitment fees from employees, but the agencies ignored the law because their revenues came directly from the fees paid by the labor migrants. Even in 2006, when agencies were allowed to collect fees of no more than NIS 3,479 per worker (about $1,000; this sum is updated annually) the agencies charged migrants significantly higher commissions, amounting to thousands of US dollars (Nathan, 2007; State Comptroller’s Report, 2010).

Thai migrants had to pay recruitment fee to the central agency in Bangkok that took care of the legal procedures (on average $9,000).Footnote 15 Those who applied to the sub-agents paid to them additional fee ranging from $990 to $2,600 (Raijman & Kushnirovich, 2012). The money paid by the migrant to the agency was divided between the recruitment agencies in Israel and Thailand (see Workers’ Hotline, 2008a, 2008b). Money transfer methods (from Thailand to Israel) included transfer accounts, cash transferred by sub-agents traveling to Israel from the country of origin, payments made in-person by migrants in Israel, together with sealed envelopes from the agencies in the country of origin (Knesset Committee for the Examination of the Problem of Foreign Workers, 2009).Footnote 16 Thus, the multiplicity of actors not only increased the complexity of the recruitment infrastructure but also increased the costs of migration.

Despite being aware of the recruitment system’s abnormalities and malpractice, Israeli authorities were unable to counteract them, due to the difficulty of proving transactions involving illegal fees that occurred outside Israel’s borders. These practices reveal the relative ungovernability of the actors involved in the recruitment process. Although there was an Israeli regulation prohibiting Israeli businesses from collecting recruiting fees from foreign job searchers, there were no mechanisms in place to prevent this regulation from being circumvented by charging labor migrants fees outside of Israel. Given that these activities took place in Thailand, it was difficult for Israel to combat them.

Data in Table 2 show that, after the implementation of the BLA the cost of migration, or the overall expenses associated with the migrants’ move (in US dollars), dramatically decreased, falling from an average of $9,149 to an average of $2,191.Footnote 17 The difference between the cost of migration “before” and “after” clearly shows the impact of the implementation of the BLA. The continuity and stability of the costs of migration over time (2014–2017) attest to the success of the BLA and the switch to a governable process monitored by state actors and non-profit actors.

Consequences of the Implementation of Bilateral Agreement for the Migrants’ Situation

The drastic reduction in recruitment fees had a major impact on the patterns of financing the costs of migration as well as the length of time required to repay the debt. The average cost of migration before the BLA was very high — about 27 times the migrants’ income in Thailand. Therefore, migrants had to rely on loans to be able to pay the high recruitment fees. The data in Table 2 indicate the percentage of each funding source out of the overall sum paid to the recruitment agencies. Before the BLA, Thai immigrants mainly relied on loans from friends, family, or banks (often by mortgaging their homes or property), or they went to the black market. Personal savings accounted for only 12% of the funding sources.

Since the implementation of the BLA, and due to the dramatic reduction in migration costs, more migrants have been able to pay for their migration through personal savings (34.6%) or loans from social networks (mostly family, but also friends) (35.6%). In 92% of these cases, these loans were interest-free. In 8% of cases, the migrants were charged a 1-3% interest rate. The percentage of mortgages provided as collateral has dropped from 35 to 9%, whereas the percentage of bank loans has increased from 8 to 19%. These modifications imply that Thais can now apply for bank loans without having to pledge their property as collateral due to the lower costs of migrating. Finally, after the BLA, only 2% of the loans came from the black market, in which the average interest rate was 30%.

One significant issue is how long it takes migrant workers to pay back their debts. This issue is important, because migrants in debt and afraid of losing their jobs and being deported tend not to report legal violations and cases of fraud (Bélanger, 2014). In other words, the precarious position of labor migrants may be further exacerbated when temporary labor is underpinned by debt contracted to cover the costs of migration (Platt et al., 2017; Shamir, 2017). Table 2 demonstrates the sharp decline in the typical repayment duration, which went from 17 months before the BLA to 7 months after its implementation. In other words, before the BLA, debt repayment required a third of the five-year stay in Israel; now, only a few months are required. This change effectively abolishes the debt bondage of migrants and enhances their autonomy.Footnote 18 We now discuss the relevance of the findings in light of existing theories.

Discussion

The recruitment practices of migrant workers in Israel have been a contested issue on both the political and economic levels. Accordingly, a systematic analysis of the impact of the BLA on the Israeli agricultural sector provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the effects of policies on migration outcomes. Table 3 summarizes the key mechanisms explaining how the change in recruiting from for-profit actors to state actors affected the process and its practical consequences for Thai migrants. By utilizing the information provided in it, we can evaluate the efficacy of the bilateral agreement in eliminating the migration industry and its illegal practices.

Before the BLA, neo-liberal configurations of governance that relied on the marketization of labor recruitment were the main reason for the emergence and development of a large for-profit migration industry in which several actors were involved. Our study shed light on the complexity of the commercial infrastructure with its multiplicity of actors (employers, private recruiting agencies, brokers, and migrants’ social networks, both in Israel and in Thailand) that sustained migration flows from Thailand to Israel until the implementation of the BLA.

This multiplicity of actors brought about a fragmentation of knowledge and consequently a fragmentation of power that resulted in the asymmetry of knowledge about job opportunities and work conditions in the host country. The recruitment process was not transparent, involving only agencies that had connections with Israeli private actors. The information was concentrated among actors linked to social networks or through sub-agents and agents of private recruitment companies.

The asymmetry of power was expressed in the lack of knowledge about employment opportunities for migrant workers and the unjust demand to pay exorbitant fees for work permits, despite being aware that such demands were illegal. This lack of knowledge and power made the migrant workers vulnerable. They feared being denied a work permit if they did not comply with the recruitment agency’s demands. Thus, the migrants’ desire to obtain a work permit generated large profits for the intermediaries who controlled the access to temporary jobs and perpetuated the precarious status of the labor migrants.

Under the auspices of the migration industry, work permits became “marketable commodities” whose prices were controlled by employment agencies that exploited prospective migrants. The migration industry developed into hierarchically linked chains of recruitment (agencies and informal brokers in Israel and Thailand) and interdependencies that pushed up the costs of recruitment for potential migrants. The practice of charging high illegal fees was pervasive, even though according to Israeli regulations, charging recruitment fees from foreign workers was prohibited, and after 2006 maximum amount of fees was allowed.

These illegal practices illustrate the relative ungovernability of the commercial organizations involved in the recruitment, because some of their operations contravened the regulatory frameworks in both countries (Thailand and Israel). Although the Israeli authorities were aware of these illegal practices, they faced difficulties in putting a stop to them. The challenges stemmed from the complexity of proving criminal transactions conducted in other countries and the lack of determination to enforce existing regulations effectively (Kemp & Raijman, 2014).

These illegal practices conducted by legal intermediaries blurred the distinction between licit and illicit practices within the framework of the temporary labor migration programs initiated by the state. The long-standing lack of law enforcement regarding the actions of Israeli and Thai recruiting organizations abroad resulted in a sprawling migration industry that at times served as the basis for human trafficking in Israel (Kemp & Raijman, 2014; Shamir, 2017).

The migration industry had significant consequences for the labor migrants’ status in the labor market. Migrants who were heavily indebted upon arrival were afraid to leave abusive employment relationships and/or return to Thailand before they had settled their debt. Thus, the debt bondage not only had a negative effect on the migrants’ earning power but also exacerbated their precarious status in Israel.

The implementation of the BLA demarketized the recruitment process, which is now managed by national offices (such as the Ministry of Labor in Thailand and PIBA in Israel), international organizations (such as the IOM in Thailand until 2020), and non-profit organizations at each of its different stages (CIMI in Israel). Private companies in Israel and Thailand are no longer involved in the process of recruitment, eliminating the previous complexity of the recruitment infrastructure. The new form of recruitment gives potential migrants more access to information about employment opportunities in Israel. The result is evident in the transparent and controlled mechanisms that broaden access to information, thus reducing the previous asymmetry in knowledge and power between the commercial actors and the migrants. The implementation of the BLA also drastically reduced the cost of migration and established the fee rates in law. The results were an increase in the governability of the recruitment process that also reduced the amount of debt that the migrants had to incur to finance their move, as well as the time needed to repay the loans.

Conclusions

The implementation of the BLA with Thailand was successful in dismantling the migration industry prevalent in Israel since the 1990s, which was the main objective of the agreement. The BLA was designed to increase workers’ awareness of their rights, to give them more in-depth information about employment conditions and rights before they arrived in Israel, to let them know where they could file complaints about violations of their rights, and who they could turn to for support and assistance.

While one might expect that increased information and awareness of rights would indirectly affect working conditions by motivating migrants to assert their rights and speak out against unfair treatment, this was not the case. One explanation might be the fact that the asymmetry of power between migrants and employers has narrowed but still exists. Previous studies revealed that the implementation of the bilateral agreement did not significantly alter the precarious status of labor migrants in the Israeli labor market. Although the BLA rectified certain injustices in the recruitment process, it did not directly address violations of the migrant workers’ rights. Therefore, it only partially reduced the migrant workers’ precariousness and vulnerability (Kushnirovich & Raijman, 2022).

Another explanation for the lack of effective change in employment conditions is the different logics governing the two dimensions: recruitment and employment conditions. While changes in recruitment methods relate to the logic of combating human trafficking through the cooperation of both the receiving and sending country, the employment conditions of the workers remain an internal matter of the receiving country - Israel. In addition, the distinct structural and institutional characteristics of the agriculture sector such as its geographical dispersion, peripherality, and the multiplicity of authorities responsible for various interests hinder effective governance in the sector and contribute to the fragmentation of institutional knowledge. Due to migrants’ limited bargaining power and the lack of efficient enforcement procedures, even existing general labor laws cannot be translated into effective protection in the labor market (Livnat & Shamir, 2022:69; Cohen & Kurlander, 2023). Thus, the potential of BLAs to protect workers’ rights is undermined by the interests of the states, which focus only on the control of the recruitment process rather than protecting the migrants’ rights in the labor market.

Notes

Bilateral agreements were signed with Bulgaria (2011), Moldova (2012), Romania (2014), Ukraine (2016), and China (2017) to recruit workers for the construction sector. In the caregiving sector, bilateral agreements were signed in 2019 with the Philippines and in 2020 with Nepal.

The cancellation of the exclusive monopoly that the Moshavim Movement had on recruitment was also related to a lawsuit submitted to the Tel Aviv Regional Labor Court in May 2000 via the Workers Hotline. The suit claimed that the Movement was illegally holding money that the workers had deposited in trust, and was refusing to give them back a sum that had reached $10 million dating back to 1996 (Kemp & Raijman, 2008).

CIMI is an independent non-profit organization assisting the State of Israel in a wide range of migration management issues. It “helps the Israeli government meet its obligations under international law and apply international standards and best practices in the field of migration” (CIMI, 2022).

In 2020 a new bilateral agreement for recruiting Thai workers for temporary work in the Israeli agricultural sector was signed. According to the new agreement, the two governments took over the handling, selection and training of applicants from the IOM, but the recruiting is still carried out via governmental institutions.

In these cases, if non-profit agents are paid for their services, the purpose is to cover expenses, not to turn to profit.

However, it should be noted that the picture emerging from the Israeli case is not one of state weakness and loss of control, but rather one in which neo-liberal governance configurations intersect with the.

commodification of migration to facilitate trade in human labor (see for example, Kemp & Raijman, 2014).

As noted earlier, before the BLA, employers had to contact private agencies in Israel that then contacted private companies in Thailand. It was these private companies that took care of the actual recruitment of the migrants.

This method was known as the “fax system” among Thai employees because it was typical for applicants to fax copies of their documentation such as passports directly to the company.

Although in most BLAs signed in Israel, the role of manpower agencies was eliminated in the recruitment process, in some cases they still have a prominent role. One example is the BLA signed in 2017 with China for bringing migrants to work in the construction sector. Some of the recruitment activities are carried out by four authorized Chinese companies under government supervision that control the authorized fees charged to the migrants. See, https://www.cimi-eng.org/_files/ugd/5d35de_16d441738d06413184ba6dfa94cb0135.pdf.

Private agencies in Israel are responsible for bringing the workers from the airport, helping them open a bank account in their name, extending passports and visas, resolving issues between the employees and their employers, organizing medical insurance, changing employees and employers, submitting applications for permits and extending the validity of permits, and transferring workers between employers.

Once in Israel, as a part of the BLA, CIMI in collaboration with the Population and Immigration Authority operates a hotline for migrant workers in Israel where they can complain about violations of their rights and contracts and receive other relevant information. The service is provided in the native languages of the migrant workers in all sectors.

The maximum fee paid was about $12,000 for migrants arriving during the last years before the implementation of the bilateral agreement.

Only a portion of the brokerage fees that Israeli manpower agencies get from manpower agencies in Thailand are reported to Israel’s tax authorities.

The actual fee for the recruitment services is currently $450. For additional services rendered to the employee throughout his stay in Israel, the manpower agency in Israel charges NIS 2,715 + VAT, or roughly $889 (Employment Service Regulations, 2006). About $852 is for an airline ticket, medical examinations, translations of documents etc.

Previous studies, however, showed that bilateral agreements did not lead to improvement of employment conditions of migrant workers. For example, in a study conducted in 2018, 68% of the respondents reported longer working hours than indicated in the contract; 55% reported a smaller number of monthly rest days than they were entitled to according to the contract; 32% reported wage withholding; 32% reported they did not receive payment for sick days; 28% reported poor living conditions; 26% reported they did not receive payment for overtime; and 17% reported that they were employed by a different employer than the one indicated in the contract (Raijman & Kushnirovich, 2019).

References

Agunias, D. (2009). Guiding the invisible hand: Making migration intermediaries work for development. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports. Research Paper 2009/22.

Anderson, J. T. (2019). The migration industry and the H-2 Visa in the United States: Employers, labour intermediaries, and the state. International Migration, 57(4), 121–135.

Anderson, J. T., & Franck, A. K. (2017). The public and the private in guestworker schemes: Examples from Malaysia and the US. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(7), 1207–1223.

Basok, T., & López-Sala, A. (2016). Rights and restrictions: Temporary agricultural migrants and trade unions’ activism in Canada and Spain. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(4), 1271–1287.

Battistella, G., & Khadria, B. (2011). Labour Migration in Asia and the Role of Bilateral.

Bélanger, D. (2014). Labor migration and trafficking among Vietnamese migrants in Asia. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 653(1), 87–106.

Black, J. (2002). Critical reflections on regulation. Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy, 27, 1–27.

Bobeva, D., & Garson, J. P. (2004). Overview of bilateral agreements and other forms of labour recruitment. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ed., Migration for employment: Bilateral agreements at a crossroads, Paris: OECD, 11–29.

Burawoy, M. (2010). From Polanyi to Pollyanna: The false optimism of global labor studies. Global Labour Journal, 1(2), 301–313.

Castles, S. (2006). Guestworkers in Europe: A resurrection? International Migration Review, 40(4), 741–766.

Chilton, A. S., & Posner, E. A. (2018). Why countries sign bilateral labor agreements. The Journal of Legal Studies, 47(S1), S45–S88.

Chilton, A., & Woda, B. (2022). The expanding universe of bilateral labor agreements. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 23(2), 1–64.

Cholewinski, R. (2015). Evaluating bilateral labour migration agreements in the light of human and labour rights. In M. Panizzon, G. Zurcher, E. Fornalé, & G. Zürcher (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of international labour migration: Law and policy perspectives (pp. 231–252). Palgrave Macmillan UK. in.

CIMI and PIBA (2018). Data for 2018. Foreign Workers’ Call Center. Accessed January 2020. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/5d35de_9dc4683a494344cabd1a9cb932e92a5f.pdf

CIMI (2022). Accessed May 2023. https://www.cimi-eng.org/about-cimi-en

Cohen, E. (1999). Thai workers in Israeli agricultural sector. In R. Nathanson, & L. Achdut (Eds.), The New workers: Wage earners from Foreign Countries in Israel (pp. 155–204). Hakibbutz Hameuhad. (In Hebrew).

Cohen, A., & Kurlander, Y. (2023). The agricultural sector as a site of trafficking in persons. Law Society & Culture, 6, 239–264. (in Hebrew).

Cruz-Del Rosario, T., & Rigg, J. (2019). Living in an age of precarity in 21st Century Asia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 49(4), 517–527.

Employment Service Regulations (2006). Fees from work applicant for work mediation. Accessed January 2020. https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/Law01/999_625.htm

Fernandez, B. (2013). Traffickers, brokers, employment agents, and social networks: The regulation of intermediaries in the migration of Ethiopian domestic workers to the Middle East. International Migration Review, 47(4), 814–843.

Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., & Sorensen, N. N. (2013). The Migration Industry and the commercialization of International Migration. Routledge.

Glyn, A. (1989). Exchange controls and policy autonomy: The case of Australia 1983-88 (Vol. 64). World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Groutsis, D., van den Broek, D., & Harvey, W. S. (2015). Transformations in network governance: The case of migration intermediaries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(10), 1558–1576.

Hernandez-Leon, R. (2005). The migration industry in the Mexico-US migratory system. California Center for Population Research. UCLA CCPR Population Working Papers. https://escholarship.org/content/qt3hg44330/qt3hg44330.pdf

Hernández-León, R. (2013). Conceptualizing the migration industry. In T. Gammeltoft-Hansen, & N. N. Sorensen (Eds.), The migration industry and the commercialization of international migration (pp. 24–44). Routledge.

Hoang, L. A. (2017). Governmentality in Asian migration regimes: The case of labour migration from Vietnam to Taiwan. Population, Space and Place, 23(3), e2019.

ILO (International Labour Organization) (2021). ILO global estimates on international migrant workers Labour Migration Branch Conditions of Work and Equality Department. Accessed January 2022. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_808935.pdf

Israel Government (2005). Government Decision #4024.

Kemp, A., & Raijman, R. (2008). "Workers" and "foreigners": The political economy of labor migration in Israel. Jerusalem: Van-Leer Institute and Kibbutz Hamehuhad (In Hebrew).

Kemp, A., & Raijman, R. (2014). Bringing in state regulations, private brokers, and local employers: A meso-level analysis of labor trafficking in Israel. International Migration Review, 48(3), 604–642.

Knesset Committee for the Examination of the Problem of Foreign Workers (2009). Protocol 28, December No 12. Accessed January 2020. http://www.knesset.gov.il/protocols/data/html/zarim/2009-12-28.html

Knesset Committee for the Examination of the Problem of Foreign Workers (2010). Protocol 10, MayNo 24. Accessed January 2020. http://www.knesset.gov.il/protocols/data/html/zarim/2010-05-10.html

Kurlander, Y. (2019). The marketization of migration: The emergence, flourishment and change of the recruitment industry for agricultural migrant workers from Thailand to Israel. (PhD). Haifa University.

Kurlander, Y. (2022). On the establishment of the agricultural migration industry in Israel’s countryside. Geography Research Forum, 41, 19–34.

Kurlander, Y., & Cohen, A. (2022). Bilateral labor agreements as sites for the meso-level dynamics of institutionalization: A cross-sectoral comparison. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 23(2), 246–265.

Kushnirovich, N. (2010). Migrant workers: Motives for migration, contingency of choice and willingness to remain in the host country. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations Communities and Nations, 10(3), 149–161.

Kushnirovich, N. (2012). Social policy and labor migration: The Israeli case. Demography and Social Economy, 1(17), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.15407/dse

Kushnirovich, N., & Raijman, R. (2022). Bilateral agreements, precarious work, and the vulnerability of migrant workers in Israel. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 23(2), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1515/til-2022-0019

Kushnirovich, N., Raijman, R., & Barak, A. (2019). The impact of government regulation on recruitment process, rights, wages and working conditions of labor migrants in the Israeli construction sector. European Management Review, 16(4), 909–922.

Lindquist, J. (2010). Labour recruitment, circuits of capital and gendered mobility: Reconceptualizing the Indonesian migration industry. Pacific Affairs, 83(1), 115–132.

Livnat, Y. (2019). Israel’s bilateral agreements with source countries of migrant workers: What is covered, what is ignored and why? Available at SRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3523087 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3523087

Livnat, Y., & Shamir, H. (2022). Gaining control? Bilateral labor agreements and the shared interest of sending and receiving countries to control migrant workers and the illicit migration industry. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 23(2), 65–94.

Malit, J., Froilan, T., & Naufal, G. (2016). Asymmetric information under the Kafala sponsorship system: Impacts on foreign domestic workers’ income and employment status in the GCC countries. International Migration, 54(5), 76–90.

Menz, G. (2013). The neoliberalized state and the growth of the Migration Industry. In T. Gammeltoft-Hansen, & N. N. Sorensen (Eds.), The migration industry and the commercialization of international migration (pp. 126–145). Routledge.

Mieres, F. (2014). The political economy of everyday precarity: Segmentation, fragmentation and transnational migrant labour in Californian agriculture [A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. The University of Manchester (United Kingdom)]. http://www.relats.org/documentos/GLOB.Mieres4.pdf

Nathan, G. (2007). Collecting illegally recruitment fees from foreign workers. The Knesset Information and Research Center (MMM). (Hebrew).

PIBA-Population and Immigration Authority (2022). Data on Foreigners in Israel. Report 3. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/zrim_q3_2022.pdf

Pittman, P. (2016). Alternative approaches to the governance of transnational labor recruitment. International Migration Review, 50(2), 269–314.

Platt, M., Baey, G., Yeoh, B. S., Khoo, C. Y., & Lam, T. (2017). Debt, precarity and gender: Male and female temporary labour migrants in Singapore. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(1), 119–136.

Raijman, R., & Kemp, A. (2007). Labor migration, managing the ethno-national conflict, and client politics in Israel. In S. Willen (Ed.), Transnational migration to Israel in global comparative context (pp. 31–50). Lexington Book.

Raijman, R., & Kushnirovich, N. (2012). Labor Migration Recruitment Practices in Israel. Ruppin Academic Center.

Raijman, R., & Kushnirovich, N. (2019). The effectiveness of the Bilateral Agreements: Recruitment, Realization of Social Rights, Living Conditions and Employment Conditions of Migrant Workers in the Agriculture, Construction and Caregiving Sectors in Israel, 2011–2018. Ruppin Academic Center, Population & Immigration Authority, and CIMI. https://4a5ab1aa-65e6-4231-856e-4bada63c8e91.filesusr.com/ugd/5d35de_ac2622fde44d485e88ff652709083df7.pdf

Rainwater, K., & Williams, L. B. (2019). Thai guestworker export in decline: The rise and fall of the Thailand-Taiwan migration system. International Migration Review, 53(2), 371–395.

Salt, J., & Stein, J., J (1997). Migration as a business: The case of trafficking. International Migration, 35(4), 467–494.

Shachar, A. (2018). Citizenship for Sale?. In A. Shachar, R. Baubock, I. Bloemraad, & V. Vink (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of citizenship (pp. 789–816). Oxford.

Shamir, H. (2017). The paradox of legality: Temporary migrant worker programs and vulnerability to trafficking. In P. Kotiswaren (Ed.), Revisiting the law and governance of trafficking, forced labor and modern slavery (pp. 471–502). Cambridge University Press.

State Comptroller’s Report (2010). Annual Report. Jerusalem. (In Hebrew). https://www.mevaker.gov.il/he/Reports/Pages/142.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

Surak, K. (2018). Migration industries and the state: Guestwork programs in East Asia. International Migration Review, 52(2), 487–523.

THA Labor (2020). Agreement between the Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of the State of Israel regarding the recruitment for employment of Thai workers for temporary Work in the Agricultural Sector in the State of Israel. https://embassies.gov.il/bangkok-en/NewsAndEvents/Pages/New-Agreement-on-Thai-Agricultural-Workers-in-Is.aspx

Tierney, R. (2011). The class context of temporary immigration, racism and civic nationalism in Taiwan. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 41(2), 289–314.

United Nations (2015). International migration report. Accessed January 2020. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf Accessed 15.12.2016.

US Department of State (2006). Victims of trafficking and violence protection act of 2000. Trafficking in Persons Report. Accessed January 2020. http://www.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2006/

Vujnovic, M. (2012). Marketization. In George Ritzer, ed., Wiley- Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization (Blackwell Publishing, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog368

Weiler, A. M., Sexsmith, K., & Minkoff-Zern, L. A. (2020). Parallel precarity: A comparison of US and Canadian agricultural guestworker programs. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 26(2), 143–163.

Wickramasekara, P. (2012). Something is better than nothing: Enhancing the protection of Indian migrant workers through Bilateral agreements and memoranda of understanding. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2032136

Wickramasekara, P. (2015). Bilateral agreements and memoranda of understanding on migration of low skilled workers: A review. Geneva: International Labor Organization. Accessed April 24, 2023. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/–migrant/documents/publication/wcms_385582.pdf

Workers Hotline (2008a). Brokerage fees: Care workers, 2007–2008 by Daniel Saphran Horen. Kav Laoved. Accessed January 2020. http://www.kavlaoved.org.il/media-view_eng.asp?id=1996

Workers Hotline. (2008b). Illegal income from migrant workers. Kav Laoved Information Sheet.

Xiang, B., & Lindquist, J. (2014). Migration infrastructure. International Migration Review, 48(1), 122–148.

Funding

This research was supported by the Center for International Migration and Integration (CIMI), Israel.

Open access funding provided by University of Haifa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of the University of Haifa (Ethics.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raijman, R., Kushnirovich, N. & Kurlander, Y. Between Marketization and Demarketization: Reconfiguration of the Migration Industry in the Agricultural Sector in Israel. Popul Res Policy Rev 43, 32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09876-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09876-5