Abstract

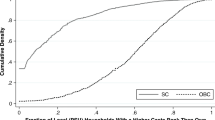

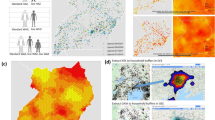

The large literature on health differentials between rural and urban areas relies almost exclusively on cross-sectional data. Bringing together the demographic literature on area-level health inequalities with the bio-physiological literature on children’s catch-up growth over time, this paper uses panel data to investigate the stability and origins of rural–urban health differentials. Using data from the Young Lives longitudinal study of child poverty, I present evidence of large level differences but similar trends in rural versus urban children’s height for age in four developing countries. Further, observable characteristics of children’s environment such as their household wealth, mother’s education, and epidemiological environment explain these differentials in most contexts. In Peru, where they do not, children’s birthweight and mothers’ health and other characteristics suggest that initial endowments—even before birth—may play an important role in explaining "residual" rural–urban child height inequalities. These latter results imply that prioritizing maternal nutrition and health is essential—particularly where rural–urban height inequalities are large. Interventions to reduce area-level health inequalities should begin even before birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The initial older cohort sample was significantly smaller in Peru than it was in the three other countries. While the number of children enrolled in wave 1 in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam, was well over 900 in each country, it was 714 in Peru.

The additional regression results reported in Peru are based on a slightly smaller sample for which none of the "additional" covariates were missing (n = 1498).

I investigated father’s education in early regression models but never found it to be statistically significantly predictive of child height for age and thus do not include it in the models presented here.

Stunting is defined as more than two standard deviations below the mean of the WHO reference population.

The traditional proxy for socioeconomic status in survey data from developing countries is using either a linear or principal components index using a variety of dummy variables reflecting household assets, quality of housing, and access to amenities, including but not limited to number of people per room, consumer durables such as radio, fridge, TV, bike, motor vehicle, etc., whether the dwelling has electricity, cement walls, and a sturdy roof, as well as the material of the floor, the main source of drinking water, the type of toilet facility, and the type of fuel used for cooking.

It is important to note that the level of aggregation of this community-level information is different in each Young Lives country. While there were 20 sentinel sites selected for sampling purposes in each country, the community data were collected at various levels of detail in these sentinel sites across the countries. The number of "communities" for which there is information on health facilities is 22 in Ethiopia, 98 in India, 82 in Peru, and 31 in Vietnam.

Birthweight is missing for 81 and 56 % of Young Lives children in Ethiopia and India, respectively; it is missing only for 12 % of the children in Peru, another reason that only data from this country are used in these further analyses.

It is not entirely clear how to interpret the association between the number of antenatal care visits and birth outcomes; a large number of visits could actually indicate a health problem. For this reason, the indicator I use is whether the woman did not have any antenatal care visits—rather than their number—as a dichotomous yes (1) or no (0) variable.

Proportion stunted over time displays very similar—inverse—patterns; see Fig. 4 in the Appendix section. The confidence intervals on stunting are larger due to the reduction in information resulting from using a dichotomous, rather than a continuous, variable.

In mothers with very high BMI (>25kg/m2), however, the coefficient remains statistically significant only at the 10 % level. Obesity has been increasingly prevalent in urban areas in Peru, and the health condition may be reducing the net health "benefits" associated with living in an urban area. Further, the consumer durables index remains statistically significant and positive in this model; it appears that among mothers with high BMI, higher socioeconomic status is still better for child health.

References

Adair, L. S. (1999). Filipino children exhibit catch-up growth from age 2 to 12 years. The Journal of Nutrition, 129(6), 1140–1148.

Adair, L. S., Fall, C. H. D., Osmond, C., Stein, A. D., Martorell, R., Ramirez-Zea, M., et al. (2013). Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: Findings from five birth cohort studies. The Lancet, 382, 525–534.

Alderman, H., Hoddinott, J., & Kinsey, B. (2006). Long term consequences of early childhood malnutrition. Oxford Economic Papers, 58(3), 450–474.

Almond, D., & Currie, J. (2010). Human capital development before age five. NBER Working Paper. Technical report. http://www.nber.org/papers/w15827.

Barnett, I., Ariana, P., Petrou, S., Penny, M., Duc, L., Galab, S., Woldehanna, T., Escobal, J., Plugge, E., & Boyden, J. (2012). Cohort Profile: The Young Lives Study. International Journal of Epidemiology,1, 1-8.

Bloom, S., Lippeveld, T., & Wypij, D. (1999). Does antenatal care make a difference to safe delivery? A study in urban Uttar Pradesh. India. Health Policy and Planning, 14(1), 38–48.

Bocquier, P., Madise, N. J., & Zulu, E. M. (2011). Is there an urban advantage in child survival in sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from 18 countries in the 1990s. Demography, 48(2), 531–558.

Boersma, B., & Wit, J. M. (1997). Catch-up growth. Endocrine Reviews, 18(5):427–431.

Bourdillon, M. (2012). Introduction (pp. 1–12). Palgrave, Pallgrave Macmillon.

Crookston, B. T., Dearden, K. A., Alder, S. C., Porucznik, C. A., Stanford, J. B., Merrill, R. M., et al. (2011). Impact of early and concurrent stunting on cognition. Matern Child Nutr, 7(4), 397–409.

Crookston, B. T., Penny, M. E., Alder, S. C., Dickerson, T. T., Merrill, R. M., Stanford, J. B., et al. (2010). Children who recover from early stunting and children who are not stunted demonstrate similar levels of cognition. The Journal of Nutrition, 140(11), 1996–2001.

Cueto, S., Escobal, J., Penny, M., & Ames, P. (2011). Tracking Disparities: Who gets left behind? Initial findings from Peru Round 3 Survey Report. Technical report. http://younglives.org.uk/publications/CR/tracking-disparities-left-behind-CR-Peru/round-3-survey-report_peru.

Currie, J. (2011). Inequality at Birth: Some causes and consequences. American Economic Review, 101(3), 1–22.

Currie, J., & Vogl, T. (2013). Early-life health and adult circumstances in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 5, 1–36.

Deaton, A. (2008). Height, Health and Inequality: The distribution of adult height in India. American Economic Review, 98(2), 468–474.

Dibley, M., Staehling, N., Nieburg, P., & Trowbridge, F. (1987). Interpretation of z-score anthropometric indicators derived from the international growth reference. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 46, 749–762.

Dornan, P. (2011). Growth, Wealth, and Inequality: Evidence from Young Lives. Technical report. http://younglives.org.uk/publications/PP/growth-wealth-inequality-policy-paper/yl_pp5_growth-wealth-and-inequality.

Escobal, J., & Flores, E. (2008). An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Peru. Technical report, Young Lives. http://bit.ly/1Eqa5Xt.

Fink, G., Günther, I., & Hill, K. (2014). Slum residence and child health in developing countries. Demography, 51(4), 1175–1197.

Fink, G., & Rockers, P. C. (2014). Childhood Growth, Schooling, and Cognitive Development: Further evidence from the Young Lives study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 182–188.

Firestone, R., Punpuing, S., Peterson, K. E., Acevedo-Garcia, D., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2011). Child Overweight and Undernutrition in Thailand: Is there an urban effect? Social Science and Medicine, 72(9), 1420–1428.

Fotso, J.-C., & Kuate-Defo, B. (2005). Socioeconomic Inequalities in Early Childhood Malnutrition and Morbidity: Modification of the household-level effects by the community SES. Health and Place, 11, 205–225.

Frankenberg, E., Friedman, J., Ingwerson, N., & Thomas, D. (2013). Child Height After a Natural Disaster. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=NEUDC2013&paper_id=391.

Golden, M. H. (1994). Is complete catch-up possible for stunted malnourished children? Eur J Clin Nutr, 48 Suppl 1:S58–70; discussion S71.

Guo, Y., Li, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, L., Chen, S., Yao, T., et al. (2015). The Effect of Air Pollution on Human Physiological Function in China: A longitudinal study. The Lancet, 386(S31), 1.

Günther, I., & Harttgen, K. (2012). Deadly Cities? Spatial inequalities in mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 38(3), 469–486.

Handa, S., & Peterman, A. (2009). Is there Catch-Up Growth? Evidence from Three Continents. http://bit.ly/1FH5N39.

Harttgen, K., & Misselhorn, M. (2006). A multilevel approach to explain child mortality and undernutrition in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. In German Development Economics Conference, volume Research Committee Development Economics, No. 20.

Hirvonen, K. (2014). Measuring catch-up growth in malnourished populations. Ann Hum Biol, 41(1), 67–75.

Hoddinott, J., & Kinsey, B. (2001). Child growth in the time of drought. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 63(4), 0305–9049.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., & Almeida-Filho, N. (2002). A glossary for health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(9), 647–652.

Kennedy, G., Nantel, G., Brouwer, I. D., & Kok, F. J. (2006). Does living in an urban environment confer advantages for childhood nutritional status? Analysis of disparities in nutritional status by wealth and residence in Angola, Central African Republic and Senegal. Public Health Nutrition, 9(2), 187–193.

Kumar, A., & Kumari, D. (2014). Decomposing the rural-urban differentials in childhood malnutrition in India, 1992–2006. Asian Population Studies.

Kumra, N. (2008). An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Andhra Pradesh, India. Technical report, Young Lives. http://bit.ly/1BiFATj.

La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (2003). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Technical report. http://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/index.php.

Lauer, J. A., Betrán, A. P., Victora, C. G., de Onís, M., & Barros, A. J. (2004). Breastfeeding Patterns and Exposure to Suboptimal Breastfeeding Among Children in Developing Countries: Review and analysis of nationally representative surveys. BMC Medicine, 2(26), 1

Lundeen, E. A., Behrman, J. R., Crookston, B. T., Dearden, K. A., Engle, P., Georgiadis, A., Penny, M. E., Stein, A. D., on behalf of the Young Lives Determinants, and of Child Growth Project Team, C. (2013). Growth faltering and recovery in children aged 1–8 years in four low- and middle-income countries: Young Lives. Public Health Nutrition,17, 2131–2137.

Mani, S. (2008). Is there Complete, Partial, or No Recovery from Childhood Malnutrition? Empirical Evidence from Indonesia. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 74(5), 691–715.

Mara, D., Lane, J., Scott, B., & Trouba, D. (2010). Sanitation and health. PLoS One,. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000363.

Mariátegui, J. (1928). Seven interpretative essays on Peruvian reality. University of Texas Austin.

Martorell, R. (1999). The nature of child malnutrition and its long-term implications. The Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 20(3), 288–292.

Matthews, Z., Channon, A., Neal, S., Osrin, D., Madise, N., & Stones, W. (2010). Examining the “urban advantage” in maternal health care in developing countries. PLoS One, 7, e1000327.

Montgomery, M., & Hewett, P. (2005). Urban Poverty and Health in Developing Countries: Household and neighborhood effects. Demography, 42(3), 397–425.

Nguyen, N. (2008). An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Vietnam.

Nolan, L. (2015). Slum Definitions in Urban India: Implications for the measurement of health inequalities. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 59–84. Technical report. http://younglives.org.uk/publications/TN/assessment-young-lives-sampling-approach-vietnam.

Outes, I., & Porter, C. (2013). Catching up From Early Nutritional Deficits? Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Economics and Human Biology, 11(2), 148–163.

Outes-Leon, I., & Dercon, S. (2008). Survey Attrition and Attrition Bias in Young Lives. Technical report, Young Lives. http://younglives.org.uk/files/YL-TN5-OutesLeon-Survey-Attrition.pdf.

Outes-Leon, I., & Sanchez, A. (2008). An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Ethiopia. Technical report, Young Lives. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/YoungLives/TN01-SampleEthiopia.pdf.

Paciorek, C. J., Stevens, G. A., Finucane, M. M., & Ezzati, M. (2013). Children’s Height and Weight in Rural and Urban Populations in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A systematic analysis of population-representative data. The Lancet Global Health, 1(5), e300–e309.

Petrou, S., & Kupek, E. (2010). Poverty and Childhood Undernutrition in Developing Countries: A multi-national cohort study. Social Science and Medicine, 71(7), 1366–1373.

Core Team, R. (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Van de Poel, E., O’Donnell, O., & Van Doorslaer, E. (2007). Are urban children re- ally healthier? Evidence from 47 developing countries. Social Science and Medicine, 65(10), 1986–2003.

Pongou, R., Ezzati, M., & Salomon, J. (2006). Household and community socioeconomic and environmental determinants of child nutritional status in Cameroon. BMC Public Health, 6(98), 1.

Pradhan, J., & Arokiasamy, P. (2010). Socio-economic Inequalities in Child Survival in India: A decomposition analysis. Health Policy, 98(2–3), 114–120.

Sahn, D. E., & Stifel, D. (2003). Exploring alternative measures of welfare in the absence of expenditure data. Review of Income and Wealth, 49(4), 463–489.

Saikia, N., Singh, A., Jasilionis, D., & Ram, F. (2013). Explaining the rural-urban gap in infant mortality in India. Demographic Research, 29(18), 473–506.

Sastry, N. (1997). What explains rural-urban differentials in child mortality in Brazil? Social Science and Medicine, 44(7), 989–1002.

Schott, W. B., Crookston, B. T., Lundeen, E. A., Stein, A. D., & Behrman, J. R. (2013). Periods of Child Growth up to Age 8 years in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam: Key distal household and community factors. Social Science and Medicine, 97, 278–287.

Smith, L., Ruel, M. T., & Ndiaye, A. (2005). Why Is Child Malnutrition Lower in Urban Than in Rural Areas? Evidence from 36 developing countries. World Development, 33(8), 1285–1305.

Sobngwi, E., Mbanya, J. C., Unwin, N. C., Porcher, R., Kengne, A. P., Fezeu, L., Mink- oulou, E. M., Tournoux, C., Gautier, J. F., Aspray, T. J., and Alberti, K. (2004). Exposure over the life course to an urban environment and its relation with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension in rural and urban Cameroon. Int J Epidemiol, 33(4):769–76

Spears, D., Ghosh, A., & Cumming, O. (2013). Open Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India: An ecological analysis of new data from 112 districts. PLoS One, 8(9), e73784.

Spears, D. (2013). How much international variation in child height can sanitation ex- plain? Technical report, World Bank. http://sanitationdrive2015.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/sanitation-height.pdf..

Srinivasan, C., Zanello, G., & Shankar, B. (2013). Rural-urban disparities in child nutrition in Bangladesh and Nepal. BMC Public Health, 13(581), 1.

Steckel, R. H. (1995). Stature and the Standard of Living. Journal of Economic Literature, 33, 1903

Tu, J., Tu, W., & Tedders, S. H. (2012). Spatial variations in the associations of birth weight with socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral factors in Georgia, USA. Applied Geography, 34, 331–344.

Vollmer, S., Harttgen, K., Subramanyam, M. A., Finlay, J., Klasen, S., & Subramanian, S. V. (2014). Association Between Economic Growth and Early Childhood Undernutrition: Evidence from 121 Demographic and Health Surveys from 36 low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 2, e225–e234.

WHO (2006). Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatrica, 450(Suppl):1–87. WHO, Geneva.

Wilson, I., & Huttly, S. (2004). Young Lives: A case study of sample design for longitudinal research. Technical report. http://bit.ly/1FLwYfc.

Woldehanna, T. (2012). Do economic shocks have a long-term effect on the height of 5- year-old children? Evidence from rural and urban Ethiopia (pp. 108–123). Palgrave Macmillon.

Young Lives (2002). Summary of the Young Lives Conceptual Framework. Technical report. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/YoungLives/YoungLives-ConceptualFramework-Overview.pdf.

Young Lives (2014). An International Study of Childhood Poverty. http://younglives.org.uk.

Zimmer, Z., Wen, M., & Kaneda, T. (2010). A multi-level analysis of urban/rural and socioeconomic differences in functional health status transition among older Chinese. Social Science and Medicine, 71(3), 559–567.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Award Numbers P32CHD04879 and T32HD007163 at Princeton University, and Award Number P2CHD058486 at the Columbia Population Research Center). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. Many thanks to Janet Currie, Doug Massey, Noreen Goldman, and Germán Rodriguez.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nolan, L.B. Rural–Urban Child Height for Age Trajectories and Their Heterogeneous Determinants in Four Developing Countries. Popul Res Policy Rev 35, 599–629 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9399-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9399-8