Abstract

Recent fertility declines in non-Western countries may have the potential to transform gender systems. One pathway for such transformations is the creation of substantial proportions of families with children of only one gender. Such families, particularly those with only daughters, may facilitate greater symmetry between sons and daughters. This article explores whether such shifts may influence gendered expectations of old age support. In keeping with patriarchal family systems, old age support is customarily provided by sons, but not daughters, in India. Using data from the 2005 Indian Human Development Survey, I find that women with sons overwhelmingly expect old age support from a son. By contrast, women with only daughters largely expect support from a daughter or a source besides a child. These findings suggest that fertility decline may place demographic pressure on gendered patterns of old age support and the gender system more broadly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While gender has been largely absent from classic discussions of the first demographic transition, which includes the transition from high to low levels of fertility, the same cannot be said for discussion around the second demographic transition, which includes fluctuations within low levels of fertility (Lesthaeghe 2010; Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006; McDonald 2000).

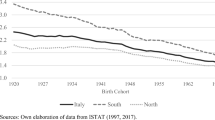

It should be noted that the NFHS does provide data on change over time in fertility in India; NFHS-1 was collected in 1992–1993, while the most recent NFHS-3 was collected in 2005–2006. However, this roughly 14-year period is not long enough to show a substantial change in the number of children in families. According to the NFHS, the mean number of children among ever married Indian women fell from 2.65 in 1992–1993 to 2.46 in 2005–2006 (author’s calculations). This decline of 0.19 children is not big enough to demonstrate the potential changes in the gender composition of families. By contrast, the mean number of children among ever married women in 2005–2006 was 2.99 in Uttar Pradesh and 1.93 in Kerala, a difference of 1.06 children.

The adoption of unrelated orphans is rare and stigmatized (Bharadwaj 2003), but the informal adoption of a male family member is acceptable because it keeps inheritance and family ties within the appropriate patriline.

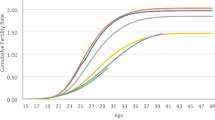

The hypothetical percentages of women that would expect support from a son were calculated by multiplying the predicted probabilities given in Fig. 5 and ESM Fig. 3 by the gender compositions for the high fertility scenario and Kerala, respectively. For example, the estimate of 91 % expecting financial support from a son in the high fertility scenario is provided by the following: (93.72*0.9255) + (3.50*0.9618) + (2.78*0.3389). Similarly, the estimate of 78 % for when the gender composition matches that of Kerala is given by (45.78*0.9255) + (27.80*0.9618) + (26.41*0.3389). These calculations also assume that the population in the high fertility scenario is not practicing son preference and the probability of having a daughter is 0.4886.

References

Allendorf, K. (2012). Like daughter, like son? Fertility decline and the transformation of gender systems in the family. Demographic Research, 27, 429–453.

Arnold, F., Kishor, S., & Roy, T. K. (2002). Sex-selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 759–785.

Bailey, M. J. (2006). More power to the pill: The impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s life cycle labor supply. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(1), 289–320.

Basu, D., & De Jong, R. (2010). Son targeting fertility behavior: Some consequences and determinants. Demography, 47(2), 521–536.

Bharadwaj, A. (2003). Why adoption is not an option in India: The visibility of infertility, the secrecy of donor insemination, and other cultural complexities. Social Science and Medicine, 56(9), 1867–1880.

Bhat, P. N. M. (2002). Returning a favor: Reciprocity between female education and fertility in India. World Development, 30(10), 1791–1803.

Bhat, P. N. M., & Zavier, A. J. F. (2003). Fertility decline and gender bias in northern India. Demography, 40(4), 637–657.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Fink, G., & Finlay, J. E. (2009). Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 79–101.

Brijnath, B. (2012). Why does institutionalized care not appeal to Indian families? Legislative and social answers from urban India. Ageing and Society, 32(4), 697–717.

Chaudhuri, S. (2012). The desire for sons and excess fertility: A household-level analysis of parity progression in India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(4), 178–186.

Chesnais, J.-C. (1992). The demographic transition: Stages, patterns, and economic implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, S. (2000). Son preference and sex composition of children: Evidence from India. Demography, 37(1), 95–108.

Coale, A. J. (1986). Demographic effects of below-replacement fertility and their social implications. Population and Development Review, 12, 203–216.

Cohen, L. (1998). No aging in India: Alzheimer’s, the bad family, and other modern things. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Das Gupta, M., & Bhat, P. N. M. (1997). Fertility decline and increased manifestation of sex bias in India. Population Studies, 51(3), 307–315.

Davis, K. (1963). The theory of change and response in modern demographic history. Population Index, 29(4), 345–366.

Davis, K., & Van den Oever, P. (1982). Demographic foundations of new sex roles. Population and Development Review, 8(3), 495–511.

Desai, S. (1995). When are children from large families disadvantaged—Evidence from cross-national analyses. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 49(2), 195–210.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47(3), 667–687.

Desai, S. B., Dubey, A., Joshi, B., Sen, M., Shariff, A., & Vanneman, R. D. (2010). Human development in India: Challenges for a society in transition. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Desai, S., & Temsah, G. (2014). Muslim and Hindu women’s public and private behaviors: Gender, family, and communalized politics in India. Demography, 51(6), 2307–2332.

Dharmalingam, A. (1994). Old-age support: Expectations and experiences in a south Indian village. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 48(1), 5–19.

Dyson, T. (2001). A partial theory of world development: The neglected role of the demographic transition in the shaping of modern society. International Journal of Population Geography, 7, 67–90.

Dyson, T. (2010). Population and development: The demographic transition. London: Zed Books.

Dyson, T., & Moore, M. (1983). On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review, 9(1), 35–60.

Grant, M. J., & Behrman, J. R. (2010). Gender gaps in educational attainment in less developed countries. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 71–89.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). The sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 519–549.

International Institute for Population (IIPS) and Macro International. (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–2006: India. Mumbai: IIPS.

Jeffery, R., & Jeffery, P. (1997). Population, gender, and politics: Demographic change in rural north India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jeffery, P., Jeffery, R., & Lyon, A. (1988). When did you last see your mother? Aspects of female autonomy in rural North India. In J. C. Caldwell, A. G. Hill, & V. H. Hull (Eds.), Micro-approaches to demographic research (pp. 321–333). London: Kegan Paul International.

Jeffery, P., Jeffery, R., & Lyon, A. (1989). Labour pains and labour power: Women and childbearing in India. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender & Society, 2(3), 274–290.

Karve, I. (1965). Kinship organization in India. Bombay: Asia Publishing House.

Kolenda, P. (1987). Regional differences in family structure in India. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Kunreuther, L. (2009). Between love and property: Voice, sentiment, and subjectivity in the reform of daughter’s inheritance in Nepal. American Ethnologist, 36(3), 545–562.

Lamb, S. (2000). White saris and sweet mangoes: Aging, gender, and body in north India. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lamb, S. (2007). Lives outside the family: Gender and the rise of elderly residences in India. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 33(1), 43–61.

Lamb, S. (2009). Aging and the Indian diaspora: Cosmopolitan families in India and abroad. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Lee, R. (2003). The demographic transition: Three centuries of fundamental change. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4), 167–190.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & Neidert, L. (2006). The second demographic transition in the United States: Exception or textbook example? Population and Development Review, 32(4), 669–698.

Malhotra, A. (2009). Remobilizing the gender and fertility connection: The case for examining the impact of fertility control and fertility decline on gender equality. Paper presented at the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population Meeting, Marrakech.

Malhotra, A., & Schuler, S. R. (2005). Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. In D. Narayan (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 71–88). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Mason, K. O. (1997). Gender and demographic change: What do we know? In G. W. Jones, R. M. Douglas, J. C. Caldwell, & R. M. D’Souza (Eds.), The continuing demographic transition (pp. 158–182). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Matysiak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2008). Fertility and women’s employment: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Population: Revue Europeenne De Demographie, 24(4), 363–384.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

Niraula, B. B. (1995). Old age security and inheritance in Nepal: Motives versus means. Journal of Biosocial Science, 27(1), 71–78.

Notestein, F. W. (1953). Economic problems of population change. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Agricultural Economists (pp. 13–31). London: Oxford University Press.

Pande, R. P. (2003). Selective gender differences in childhood nutrition and immunization in rural India: The role of siblings. Demography, 40(3), 395–418.

Presser, H. B., & Sen, G. (Eds.). (2000). Women’s empowerment and demographic processes: Moving beyond Cairo. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Registrar General [India]. (2009). Sample registration system bulletin (Vol. 44, p. 1). New Delhi: Registrar Gender.

Registrar General [India]. (2012). Sample registration system statistical report 2010. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Reher, D. S. (2007). Towards long-term population decline: A discussion of relevant issues. European Journal of Population: Revue Europeenne De Demographie, 23(2), 189–207.

Reher, D. S. (2011). Economic and social implications of the demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 37, 11–33.

Rele, J. R. (1987). Fertility levels and trends in India, 1951–1981. Population and Development Review, 13(3), 513–530.

Saavala, M. (2001). Fertility and familial power relations: Procreation in south India. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Shaw, A. (2004). British Pakistani eldelry without children: An invisible minority. In P. Kreager & E. Schroder-Butterfill (Eds.), Ageing without children: European and Asian perspectives (pp. 198–222). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

United Nations. (2011). World population prospects, the 2010 revision. New York: Population Division, United Nations.

Vatuk, S. (1990). “To be a burden on others”: Dependency anxiety among the elderly in India. In O. M. Lynch (Ed.), Divine passions: The social construction of emotion in India (pp. 64–90). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Vera-Sanso, P. (2004). They don’t need it, and I can’t give it: Filial support in South India. In P. Kreager & E. Schroder-Butterfill (Eds.), Ageing without children: European and Asian perspectives (pp. 77–105). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Vlassoff, C. (1990). The value of sons in an Indian village—How widows see it. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 44(1), 5–20.

Watkins, S. C., Menken, J. A., & Bongaarts, J. (1987). Demographic foundations of family change. American Sociological Review, 52(3), 346–358.

Ye, H., & Wu, X. (2011). Fertility decline and educational inequality in China. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, DC.

Yount, K. M., Zureick-Brown, S., Halim, N., & LaVilla, K. (2014). Fertility decline, girls’ well-being, and gender gaps in children’s well-being in poor countries. Demography, 51(2), 535–561.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America in New Orleans and the 2013 “Human Development in India: Evidence from IHDS” Conference in New Delhi. The author would like to thank participants at the IHDS conference for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allendorf, K. Fertility Decline, Gender Composition of Families, and Expectations of Old Age Support. Popul Res Policy Rev 34, 511–539 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9354-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9354-5