Abstract

According to a certain kind of naïve or folk understanding of physical matter, everyday ‘solid’ objects are composed of a homogeneous, gap-less substance, with sharply defined boundaries, which wholly fills the space they occupy. A further claim is that our perceptual experience of the environment represents or indicates that the objects around us conform to this sort of conception of physical matter. Were this further claim correct, it would mean that the way that the world appears to us in experience conflicts with the deliverances of our best current scientific theories in the following respect: perceptual experience would be intrinsically misleading concerning the structure of physical matter. I argue against this further claim. Experience in itself is not committed to, nor does it provide evidence for, any such conception of the nature of physical matter. The naïve/folk conception of matter in question cannot simply be ‘read-off’ from perceptual appearances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Published the following year, 1928, with the title “The Nature of the Physical World”.

Wilfrid Sellars explicitly connected his famous distinction between the ‘Manifest Image’ and the ‘Scientific Image’ with Eddington’s ‘two tables’.

It is worth noting that we have here a recurrence of the essential features of Eddington’s ‘two tables’ problem—the two tables being, in our terminology, the table of the manifest image and the table of the scientific image. There the problem was to ‘fit together’ the manifest table with the scientific table. Here the problem is to fit together the manifest sensation with its neurophysiological counterpart. And, interestingly enough, the problem in both cases is essentially the same: how to reconcile the ultimate homogeneity of the manifest image with the ultimate non- homogeneity of the system of scientific objects.” (Sellars 1962, 35–36).

Of course, the idea that experience is the source of our mistaken folk-beliefs about physical matter is not required for the thesis that experience clashes with science. It could be, for example, that our folk conception of matter is innate and not derived from experience—and yet the experiential content might still clash with science.

The label ‘structural realism’ is due originally to Maxwell (1970). Whereas an epistemic structural realist (e.g. Russell 1927; Worrall 1989) holds that all that science can allow us to know about the (unobservable) world is its relational structure, an ontic structural realist (e.g. French and Ladyman 2003; Esfeld 2009) holds that ultimately all there is to reality/nature is such relational structure.

See, for example, Nanay (2018).

The radii of the atoms of different elements vary from around 30–300 pm. The distance from the nucleus to the surrounding electrons is thus typically over 10,000 times larger than the size of the nucleus itself, which is 0.01–0.001 picometres in radius. Though of course, one of the bizarre, counter-intuitive features of matter at this scale is that the orbiting electrons don’t have sharply defined locations, but rather a probability distribution of possible locations.

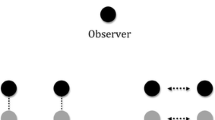

And after all, what would be the evolutionary purpose of a visual system ascribing spatial properties to objects right down to the microscopic scale, a scale at which the system cannot make spatial discriminations, rather than simply remaining neutral about invisibly microscopic spatial properties?

I also recount and discuss this anecdote in Raleigh (2009), though in the service of a quite different philosophical point.

See p. 151 of the 2nd edition of Anscombe’s An Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (1963/1959). Many thanks to Sofia Miguens for help tracking down this reference.

It is perhaps worth noting that this may not necessarily be an unwelcome consequence. Chalmers (forthcoming) argues for a form of ‘spatial functionalism’ on which the content of spatial experience is, roughly: whatever physical property is the normal cause of this kind of experience. Chalmers comments: ‘If spatial functionalism is correct… then systematic lifelong illusions about space are much more difficult to sustain. In particular, if we pick out spatial properties as the normal causes of spatial experiences, then situations in which spatial experiences are normally caused by properties other than the spatial properties they represent will be ruled out.’ (Chalmers forthcoming, 24).

See Clark (2000).

Though of course if you already have a theory of visual content according to which we are constantly subject to systematic illusions, then our folk theory/grasp of expected visual appearances could not provide this kind of useful heuristic/guide.

And if the line of thought in Sect. 3 was correct, when we think in terms of the representational content of experience, nor should we reasonably take our normal visual experience of macroscopic objects to positively represent a lack of microscopic particles and gaps.

See Chalmers (forthcoming).

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at events at V. U. Amsterdam, Ben-Gurion University, University of Warwick, H.S.E. Moscow, Ruhr University Bochum, University of Porto, University of Antwerp and the United Arab Emirates University. I am grateful to the audiences on all those occasions for their feedback. Many thanks in particular to Alma Barner, Ori Beck, Silver Bronzo, Peter Brössel, José Pedro Correia, Luca Corti, Alison Fernandes, Laura Gow, Jonathan Knowles, Kevin Lande, Raamy Majeed, Tom McClelland, William McDonald, Phillip Meadows, Sofia Miguens, Bence Nanay, Jim Pryor, Susanna Siegel, Charles Travis, Dan Williams and Nick Wiltsher for their comments and criticisms. Finally, thanks also to an anonymous referee for this journal for her/his helpful report. Research on this paper has been supported by an Emmy Noether Grant from the German Research Council (DFG), reference number BR 5210/1-1.

References

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1963/1959) An Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (2nd Revised ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Bayne, T. (2009). Perception and the reach of phenomenal content. Philosophical Quarterly,59(236), 385–404.

Baysan, U., & Wilson, J. (2017). Must strong emergence collapse? Philosophica,91, 49–104.

Brogaard, B. (2013). Do we perceive natural kind properties? Philosophical Studies,162(1), 35–42.

Cambell, J., & Cassam, Q. (2014). Berkeley’s Puzzle: What does experience teach us? Oxford: OUP.

Carrasco, M. (2011). Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vision Research,51, 1484–1525.

Casullo, A. (1986). The spatial structure of perceptual space. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research,46(4), 665–671.

Chalmers, D. (forthcoming). Three puzzles about spatial experience. In A. Pautz and D. Stoljar (eds.), Themes from Ned Block. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Clark, A. (2000). A Theory of Sentience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cussins, A. (1990). Content, conceptual content, and nonconceptual content. In Y. Gunther (Ed.), Essays on Nonconceptual Content (pp. 133–163). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cutter, B. (forthcoming) Indeterminate perception and color relationism. Analysis.

Dretske, F. (1995). Naturalizing the Mind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Eddington, A. (1928). The Nature of the Physical World. London: Dent.

Eddington, A. (1939). Philosophy of Physical Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Esfeld, M. (2009). The modal nature of structures in ontic structural realism. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science,23, 179–194.

French, S., & Ladyman, J. (2003). Remodelling structural realism: Quantum physics and the metaphysics of structure. Synthese,136, 31–56.

Ganson, T., & Bronner, B. (2013). Visual prominence and representationalism. Philosophical Studies,164(2), 405–418.

Gillet, C. (2002). Strong emergence as a defense of non-reductive physicalism. Principia: An International Journal of Epistemology,6(1), 87–120.

Gillet, C. (2003). The metaphysics of realization, multiple realizability, and the special sciences. The Journal of Philosophy,100, 591–603.

Gobell, J., & Carrasco, M. (2005). Attention alters the appearance of spatial frequency and gap size. Psychological Science,16(8), 644–651.

Masrour, F. (2015). The geometry of visual space and the nature of visual experience. Philosophical Studies,172(7), 1813–1832.

Maxwell, G. (1970). Structural realism and the meaning of theoretical terms. In S. Winokur & M. Radner (Eds.), Analyses of theories, and methods of physics and psychology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Meadows, P. (2011). Contemporary arguments for a geometry of visual experience. European Journal of Philosophy,19(3), 408–430.

Nanay, B. (2010). Attention and perceptual content. Analysis,70, 263–270.

Nanay, B. (2011). Do we see apples as edible? Pacific Philosophical Quarterly,92(3), 305–322.

Nanay, B. (2018). Blur and perceptual content. Analysis,78(2), 254–260.

Peacocke, (1992). Scenarios, concepts, and perception. In Tim Crane (Ed.), The Contents of Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pereboom, D. (2002). Robust non-reductive materialism. Journal of Philosophy,99, 499–531.

Price, R. (2009). Aspect-switching and visual phenomenal character. Philosophical Quarterly,59(236), 508–518.

Raleigh, T. (2009). Understanding how experience ‘seems’. European Journal of Analytic Philosophy,5(2), 67–78.

Russell, B. (1927). The Analysis of Matter. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Sellars, W. (1962). Philosophy and the scientific image of man. In Robert Colodny (Ed.), Frontiers of Science and Philosophy. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Siegel, S. (2006). Which properties are represented in perception? In J. Hawthorne & T. Gendler Szabo (Eds.), Perceptual Experience (pp. 481–503). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stazicker, J. (2011). Attention, visual consciousness and indeterminacy. Mind & Language,26(2), 156–184.

Tye, M. (1995). Ten Problems of Consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Van Cleve, J. (2002). Thomas Reid’s geometry of visibles. The Philosophical Review,111, 373–416.

Wagner, M. (2006). The Geometries of Visual Space. London: Erlbaum.

Wilson, J. (2010). Non-reductive physicalism and degrees of freedom. British Journal for Philosophy of Science,61(2), 279–311.

Wilson, J. (2011). Non-reductive realization and the powers-based subset strategy. The Monist,94, 121–154.

Wilson, J. (2015). Metaphysical Emergence: Weak and Strong. In T. Bigaj & C. Wuthrich (Eds.), Metaphysics in Contemporary Physics: Poznan studies in the philosophy of the sciences and the humanities (pp. 345–402). Leiden: Brill.

Worrall, J. (1989). Structural realism: The best of both worlds? In D. Papineau (Ed.), The Philosophy of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yeshurun, Y., & Carrasco, M. (2008). The effects of transient attention on spatial resolution and the size of the attentional cue. Perception and Psychophysics,70(1), 104–113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raleigh, T. Science, substance and spatial appearances. Philos Stud 177, 2097–2114 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01300-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01300-5