Abstract

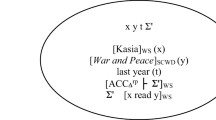

We argue that sensitivity to the distinction between the tensed notion of being something and the tensed notion of being located at the present time serves as a good antidote to confusions in debates about time and existence, in particular in the debate about how to characterise presentism, and saves us the trouble of going through unnecessary epicycles. Both notions are frequently expressed using the tensed verb ‘to exist’, making it systematically ambiguous. It is a commendable strategy to avoid using that verb altogether in these contexts and to use quantification and a location predicate instead.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Damiano Costa has recently advocated a theory of persistence through time—transcendentism, as he calls it—according to which for a continuant (Costa uses the term ‘object’) to exist at a time is for it to participate in certain events that are located at that time (Costa 2017). This theory is similar to the view put forward here. However, unlike Costa we do not offer a theory of temporal existence, but make the more modest claim that ordinary usage licences a construal of ‘exists at t’ as ‘is located at t’ even when applied to continuants.

There arguably is also a use of ‘the present time’ according to which it serves as temporally rigid designator of the time of utterance, in just the same way the indexical ‘now’ does. This is evidently not the use we intend here. Rather, we here understand ‘the present time’ to function in such a way that ‘Always, for all times t, at t, t is the present time’ comes out true.

Endorsement of the permanentist thesis does not yet commit one to the claim that the tensed notion of existence, used to formulate that thesis, is basic.

Deasy (2017) insists that the quantifiers of predicate logic ‘are tenseless’—in which case so would be ‘exists’ in the second sense here identified in which it is equivalent to ‘is something’. Deasy’s sole argument for this contention is that if ‘∃xDodo(x)’ were tensed, ‘P∃xDodo(x)’ would have to be equivalent either to ‘PN∃xDodo(x)’ or to ‘PS∃xDodo(x)’, which it is decidedly not (where ‘P’ is ‘Sometimes in the past’, ‘N’ is ‘Now’, and ‘S’ is ‘Sometimes’). Given that ‘Now’ is temporally rigid, i.e. always takes us back to the time of utterance, the subjunctive is plain false: ‘P(It rains in Oslo)’ is neither tense-logically equivalent to ‘PN(It rains in Oslo)’ nor to ‘PS(It rains in Oslo)’; and yet who would want to deny that ‘It rains in Oslo’ is tensed? Despite his insistence that quantification is tenseless, Deasy nonetheless goes on to consider transientism as a serious contender, where transientism is the following thesis: S∃xP¬∃y(y = x) & S∃xF¬∃y(y = x) (with ‘F’ being short for ‘Sometimes in the future’). Deasy offers the following informal gloss on this thesis: ‘As time passes, some things begin to be, and some things cease to be’. Yet, if quantification really is tenseless, then relative to any assignment to the variable ‘x’, if ‘¬∃y(y = x)’ is true at one time of evaluation it is true at any time of evaluation; and it evidently cannot be that sometimes, ‘∃x¬∃y(y = x)’ holds. Accordingly, to the extent that transientism is at all coherent, Deasy is forced to deny that temporal operators shift the time of evaluation for the clause they embed. This goes against the standard conception of the significance of such operators. Deasy indeed contemplates an alternative view, labelled ‘locator’, according to which such operators ‘are implicit quantifiers over instants of time which restrict the explicit individual quantifiers (∀, ∃) in their scope to things located at the relevant instant’. But read in this way, the thesis of transientism can no longer be glossed in the manner Deasy suggests: no longer (not yet) being located at the present time does not entail no longer (not yet) being something. (In fact, Deasy discusses locator merely in the context of the non-transientist B-theory; but this observation evidently does nothing to alleviate the problem.).

Torrengo (2012: 126–127) would seem to disagree when he suggests that tensed notions of existence not only ‘contain implicit reference to the time of utterance’, but furthermore ‘seem to require reference to the temporal location of the entities to which we apply’ them. Introducing an allegedly tenseless notion of ‘simple existence’ that contains no such reference, he nonetheless allows for temporal variation in that notion’s range of application (i.e. the domain of quantification). Accordingly, claims about what exists simpliciter are after all tensed, on his view, in that they can vary in truth-value over time. To stabilise this combination of thoughts, Torrengo draws a somewhat artificial distinction between the tensedness of claims attributing simple existence and the tensedness of the notion of simple existence itself (ibid.). We see no reason to follow Torrengo here. The notion of what exists simpliciter—i.e. the notion of being in the range of the existential quantifier—that figures in tensed claims sensitive to tense-logical embedding, is itself tensed. Yet, applications of the notion do not—pace Torrengo—attribute any temporal location to the things to which it is applied.

Eternalists take the latter claim to likewise have its truth-value eternally; temporaryists will disagree only on assumption that ‘is located at’ is existence-entailing, which it may well not be.

We here use the existential quantifier as unrelativised, so that for temporaryists and permanentists alike, whenever ‘∃y(y = x)’ is true, it is true simpliciter. Even then, there is the option to introduce a time-relative existential quantifier in addition, thereby allowing for statements of the form ‘∃ty(y = x)’, where the latter is intended to be equivalent to ‘∃y(y = x & y is located at t)’. This option in no way affects our discussion.

References

Cameron, R. (2017). On characterizing the presentism/externalism and actualism/possibilism debates. Analytic Philosophy,57, 110–140.

Correia, F., & Rosenkranz, S. (2015). Presentism without presentness. Thought,4, 19–27.

Costa, D. (2017). The transcendentist theory of persistence. The Journal of Philosophy,114, 57–75.

Crisp, T. M. (2004a). On presentism and triviality. In D. W. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaphysics (Vol. 1, pp. 15–20). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crisp, T. M. (2004b). Reply to Ludlow. In D. W. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaphysics (Vol. 1, pp. 37–46). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deasy, D. (2017). The triviality argument against presentism. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1601-y.

Deng, N. (2018). What is temporal ontology? Philosophical Studies,175, 793–807.

Ingram, D., & Tallant, J. (2018). Presentism. In N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2018 edition). <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/presentism/.

Lombard, L. B. (1999). On the alleged incompatibility of presentism and temporal parts. Philosophia,27, 253–260.

Lombard, L. B. (2010). Time for a change: A polemic against the presentism–eternalism debate. In J. K. Campbell, M. O’Rourke, & H. S. Silverstein (Eds.), Time and identity (pp. 49–77). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Ludlow, P. (2004). Presentism, triviality, and the varieties of tensism. In D. W. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaphysics (Vol. 1, pp. 21–36). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, U. (2005). The presentist’s dilemma. Philosophical Studies,122, 213–225.

Meyer, U. (2013). The triviality of presentism. In R. Ciuni, et al. (Eds.), New papers on the present: Focus on presentism (pp. 67–87). Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Miller, K. (2013). Presentism, eternalism, and the growing block. In H. Dyke & A. Bardon (Eds.), A companion to the philosophy of time (pp. 345–364). Oxford: Blackwell.

Mozersky, M. J. (2011). Presentism. In C. Callender (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of time (pp. 122–144). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sider, T. (1999). Presentism and ontological commitment. The Journal of Philosophy,96, 325–347.

Sider, T. (2006). Quantifiers and temporal ontology. Mind,115, 75–97.

Stoneham, T. (2009). Time and truth: The presentism-eternalism debate. Philosophy,84, 201–218.

Tallant, J. (2014). Defining existence presentism. Erkenntnis,79, 479–501.

Thomasson, A. (1999). Fiction and metaphysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Torrengo, G. (2012). Time and simple existence. Metaphysica,13, 125–130.

Williamson, T. (2013). Modal logic as metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, D. W. (1998). Temporary intrinsics and presentism. In P. van Inwagen & D. W. Zimmerman (Eds.), Metaphysics: The big questions (pp. 206–219). Oxford: Blackwell.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the European Commission's H2020 programme under grant agreement H2020-MSCA-ITN-2015-675415 and the Swiss National Science Foundation (project BSCGI0_157792).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Correia, F., Rosenkranz, S. Temporal existence and temporal location. Philos Stud 177, 1999–2011 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01295-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01295-z