Abstract

Philosophers and psychologists often assume that mirror reflections are optical illusions. According to many authors, what we see in a mirror appears to be behind it. I discuss two strategies to resist this piece of dogma. As I will show, the conviction that mirror reflections are illusions is rooted in a confused conception of the relations between location, direction, and visibility. This conception is unacceptable to those who take seriously the way in which mirrors contribute to our experience of the world. My argument may be read as an advertisement of the neglected field of philosophical catoptrics, the philosophical study of the optical properties of mirrors. It enables us to recast familiar issues in the philosophy of perception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

What I here call ‘specular illusionism’ is a specific version of the view that mirror appearances are illusions. There are other versions of this view, because there may be other reasons to think mirror appearances are illusory. For example, many think that mirrors give an illusion of left/right reversal; see Block (1974).

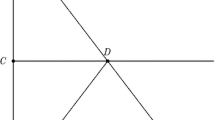

For plane mirrors, the reflected rays lie in the plane of incidence, and incident and reflected rays make equal but opposite angles with the perpendicular to the mirror surface (Katz 2002).

Mizrahi (forthcoming) rightly emphasises that phenomenologically speaking, mirrors are likely to be more complex than the physical story alone would suggest.

Jason Leddington suggested to me that the distinctive aim of theatrical magic is to produce illusions of impossible events.

To see Rotating Snakes and several other peripheral drift illusions, see Kitaoka’s website: http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/~akitaoka/index-e.html.

I take the inference from 1 to 2 to be entirely straightforward.

See Turbayne (1959) for a history of this principle.

A similarly minimalist account is suggested by Boyd Millar. He thinks that an account that construes mirror perception in terms of the perception of virtual objects is unnecessarily complicated. Such an account, he writes, “ought to be rejected for that reason: a far simpler account is that when you see something reflected in a mirror what you see is an ordinary physical object” (2011, 568n19).

I am talking here about perception, where what we become aware of is experienced as ‘out there’ in the world. The notion can also be used derivatively, for instance to indicate what part of our visual field is occupied by an after-image or phospheme.

A point notoriously emphasised by Kant, KrV A264/B320.

Further support for this can be found in a study by Jones and Bertamini (2007). When people simultaneously see an object both head-on and reflected in a mirror, the mirror perception improves the person's estimation of the size and distance of the relevant object. As Millar explains, if we were always fooled by reflections in mirrors, "then in such situations a subject would perceive two objects, and the properties of the one would not provide any information about the size and distance of the other" (2011, 567).

This case is taken from Yasunari Kawabata’s novel Snow Country (1956) (雪国 Yukiguni, 1948).

Mizrahi (forthcoming) concurs, it seems, when she agrees that we must explain the possibility of erroneously perceiving objects as being located behind a mirror in terms of phenomenological similarities between mirror perception and perception of empty space.

Consider also the visibility of soap bubbles. While a bubble itself lacks colour, due to how the multi-layered surface reflects and transmits specific frequencies of light, the thin outer layer of a soap bubble creates an optical interference that makes the bubble appear coloured (such ‘colours’ are called ‘Newton’s colours’). The bubble is visible, but there is no way that it looks in and of itself.

References

Bertamini, M., Lawson, R., & Liu, D. (2008). Understanding 2D projections on mirrors and on windows. Spatial Vision, 21(3–5), 273–289. doi:10.1163/156856808784532527.

Block, N. (1974). Why do mirrors reverse right/left but not up/down. The Journal of Philosophy, 71(9), 259–277.

Casati, R. (2012). Illusions and epistemic innocence. In C. Calabi (Ed.), Perceptual illusions. Philosophical and psychological essays (pp. 192–201). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Clark, A. (1996). Three varieties of visual field. Philosophical Psychology, 9(4), 477–495. doi:10.1080/09515089608573196.

Evans, G. (1982). In J. McDowell (Ed.), The Varieties of Reference. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Jones, L. A., & Bertamini, M. (2007). Through the looking glass: How the relationship between an object and its reflection affects the perception of distance and size. Perception, 36, 1572–1594. doi:10.1068/p5605.

Katz, M. (2002). Introduction to geometrical optics. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific.

Mac Cumhaill, C. (2011). Specular space. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, cxi(3), 487–495. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9264.2011.00320.x.

Martin, M. G. F. (2016). Elusive objects. Topoi. doi:10.1007/s11245-016-9389-9.

Matthen, M. (forthcoming). Some principles of ephemeral vision. In C. Mac Cumhaill & T. Crowther (Eds.), Perceptual ephemera. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Millar, B. (2011). Sensory phenomenology and perceptual content. Philosophical Quarterly, 61, 558–576. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9213.2011.696.x.

Mizrahi, V. (forthcoming). Perceptual media, glass and mirrors. In C. Mac Cumhaill & T. Crowther (Eds.), Perceptual ephemera. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sellars, W. (1997). Empiricism and the philosophy of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Turbayne, C. M. (1959). Grosseteste and an ancient optical principle. Isis, 50(4), 467–472. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9213.2011.696.x.

Vendler, Z. (1994). The ineffable soul. In R. Warner & T. Szubka (Eds.), The mind body problem: A guide to the current debate (pp. 317–328). Oxford: Blackwell.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this material were presented to audiences in Toronto, Washington, and Antwerp. Special thanks go to Mike Bruno, Roberto Casati, Caitlin Dolan, Laura Gow, Benj Hellie, Grace Helton, Mark Kalderon, Mohan Matthen, Chris Meyns, Boyd Millar, Vivian Mizrahi, Bence Nanay, and Nick Young.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steenhagen, M. False reflections. Philos Stud 174, 1227–1242 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0752-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0752-x