Abstract

In contentless experience (sometimes termed pure consciousness) there is an absence of mental content such as thought, perception, and mental imagery. The path to contentless experience in meditation can be taken to comprise the meditation technique, and the experiences (“interim-states”) on the way to the contentless “goal-state/s”. Shamatha, Transcendental, and Stillness Meditation are each said to access contentless experience, but the path to that experience in each practice is not yet well understood from a scientific perspective. We have employed evidence synthesis to select and review 135 expert texts from those traditions. In this paper we describe the techniques and interim-states based on the expert texts and compare them across the practices on key dimensions. Superficially, Shamatha and Transcendental Meditation appear very different to Stillness Meditation in that they require bringing awareness to a meditation object. The more detailed and systematic approach taken in this paper indicates that posturally Shamatha is closer to Stillness Meditation, and that on several other dimensions Shamatha is quite different to both other practices. In particular, Shamatha involves greater measures to cultivate attentional stability and vividness with respect to an object, greater focusing, less tolerance of mind-wandering, more monitoring, and more deliberate doing/control. Achieving contentless experience in Shamatha is much slower, more difficult, and less frequent. The findings have important implications for taxonomies of meditation and for consciousness, neuroscientific, and clinical research/practice, and will provide new and useful insights for meditation practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Meditation has played an important role in Asia for thousands of years, but in western countries it is now also the subject of enormous public interest (Goleman & Davidson, 2017). Up until the early 1990s, Transcendental Meditation (“TM”) had received the most research attention (Lutz et al., 2007; Shear, 1990b), but in the last 20 years the main focus has been on a group of practices known as mindfulness meditation (Lutz et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2015). TM is said to aim for an experience that is “contentless”, in that mental content such as thought, sense-perception, body-perception, and mental imagery is absent (Pearson, 2013; Shear, 2006c). Contentless experience has also been referred to as pure consciousness, consciousness as such, and minimal phenomenal experience, and it is an important subject for cognitive science and philosophy (Costines et al., 2021; Gamma & Metzinger, 2021; Josipovic & Miskovic, 2020; Metzinger, 2020, 2022; Millière, 2020; Millière et al., 2018). One of the major forms of mindfulness practice known as shamatha is also said to aim for contentless experience (Gimello, 1978; Jones, 1993; Markovic & Thompson, 2016; Wallace, 2007b).

In the TM tradition, the TM technique is understood to have formed part of the Vedic tradition of ancient India (Pearson, 2013; Roth, 2018; Shear, 2006c; cf. Williamson, 2010, p. 86). Maharishi Mahesh Yogi is said to have revitalized the technique in the 1950s, recognizing its value as a standalone practice extracted from its traditional Vedic setting (Pearson, 2013; Rosenthal, 2011/2012; Shear, 2006c). Regularly accessing contentless experience in TM is said to improve mental and physical health and wellbeing, and prompt development of higher states of consciousness in daily life (Pearson, 2013). Most of the scientific studies on contentless states in meditation have centred on TM (see, e.g., Vieten et al., 2018; for a detailed review of the TM research, see Pearson, 2013, pp. 399–430).

The meditation expert and scholar Alan Wallace teaches a classic Tibetan Buddhist form of shamatha (Wallace, 2006a). Wallace presents shamatha primarily from the perspective of the Dzogchen tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. In that tradition it is understood that shamatha develops attentional qualities that are necessary for the effective practise of insight meditation (Sanskrit: vipashyana) (Wallace, 2006a, 2011a, b). Through insight meditation and other advanced practices it is said that meditators can achieve enlightenment (also known as pristine or nondual awareness) (Josipovic, 2021; Wallace, 2005, 2011a, b, 2012). Shamatha practice is also said to improve mental and physical health and wellbeing (Wallace, 2006a). The shamatha practice described by Alan Wallace (“Shamatha”) has been researched at length in the past 10 years (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2011; Rosenberg et al., 2015; Zanesco et al., 2019).

There are differences between the TM and Shamatha techniques, but there is also an obvious similarity, in that each involves bringing awareness to a meditation object. A third practice said to access contentless experience is Stillness Meditation (McKinnon, 1983/2016; Meares, 1967/1968). That practice does not involve a meditation object, and therefore provides a striking illustration of the diversity in techniques that are said to lead to contentless experience. Stillness Meditation was designed in the 1960s for the treatment of anxiety and pain, and has been used in clinical practice up to the present day. This form of meditation has gone almost unnoticed in contemplative research. In the full landscape of meditation techniques (see, e.g., Matko et al., 2021), and the subset thought to access contentless experience, Stillness Meditation stands out because it is extremely simple: It is said to involve “doing nothing” (McKinnon, 2011, p. 45). Examining how Stillness Meditation leads to contentless experience may help to understand how more complex techniques access such states. The “methodological principle” here is that “to understand something complex turn to its simple forms” (Forman, 1998b, p. 185; Metzinger, 2018, 2020).

Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation are the focus of this paper. A high-level overview of the three practices is provided in Fig. 1.

High-level overview of the three practices. Entries for each feature reflect the understanding within each meditation tradition. The primary purpose of reaching the contentless goal-states is as typically stated in modern texts for the general public (e.g., McKinnon, 1983/2016; Roth, 2018; Wallace, 2011b). A secondary purpose or benefit of reaching the Shamatha goal-state is reducing anxiety, improving mental and physical health/wellbeing, and achieving personal growth/development, and a further purpose of reaching the TM goal-state is that it is said to lead to higher states of consciousness in daily life

This paper draws a distinction between “goal-state/s” and “interim-states”. The goal-state/s in the three practices are contentless experience, and the interim-state/s are any experience on the way to the goal-state/s. In Woods et al. (2022a) we have described the goal-states. The current paper is concerned with the techniques and interim-states.

Researchers need high quality understandings of the techniques and interim-states because those elements are critical to the meditation practices. Metaphorically, the technique and interim-states are the path to the goal-state/s: contentless experience. In each practice, the meditator must apply the technique correctly, and move through the interim-states, in order to access the goal-state/s. Even prior to reaching the goal-state/s, progress in the interim-states is said to lead to positive changes in the meditator’s daily life (e.g., Wallace, 2006a). In a practice like Shamatha, where the goal-state is very difficult to attain (see Section 2.1.7), most meditators will spend all of their practice in the interim-states.

To learn about a meditation technique or experience, it is essential that researchers consider understandings of experts within the meditation tradition (Gyatso, 2016; Lindahl et al., 2014). Traditional understandings of experts, in written form, are a major source of information about meditation practices. Where researchers have regard to these expert accounts, they typically concentrate on a small subset of the total publications (e.g., Lindahl et al., 2014; Lutz et al., 2015; Wahbeh et al., 2018). There are often thousands of traditional publications for a particular practice, and it is not practicable to review them all. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been any research that has identified the features of the techniques and interim-states in Shamatha, TM or Stillness Meditation using expert texts selected and reviewed by way of a formal, structured, and transparent process.

A second gap in the research is that there has not been any detailed comparison of the techniques or interim-states across the three practices. A comparison of this kind would allow each practice to be understood relative to the other approaches. That would provide a much richer understanding than considering each practice in isolation.

This paper addresses these two gaps in research. In Sections 2.1 to 2.3, we describe the main features of the Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation techniques and interim-states, based on expert texts selected and reviewed using an evidence synthesis process. Evidence synthesis is a rigorous and transparent method, and in the present context is aimed at achieving a precise and reliable understanding of how the techniques and interim-states are described in the relevant traditions. In Section 2.4, we compare the techniques and interim-states across the practices on a number of key dimensions.

1 Method

1.1 Evidence synthesis

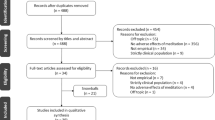

The present paper, in conjunction with Woods et al. (2020), forms an evidence synthesis that accords with the ENTREQ reporting guidelines for qualitative evidence syntheses (Tong et al., 2012). The Online Resource for this paper details the section/s that satisfy each of the 21 items on the ENTREQ checklist. The evidence synthesis process involved five steps. The first three are summarized in Fig. 2. The complete method for these three steps has been published as a separate document (Woods et al., 2020). The fourth and fifth steps in the evidence synthesis process are described in Fig. 3.

Representation of steps 1 to 3 in the evidence synthesis process. The first step was to select for each practice samples of publications by expert/s with outstanding qualifications. Alan Wallace was selected as the expert for Shamatha; Craig Pearson, Norman Rosenthal, Bob Roth, Jonathan Shear, and Fred Travis as the experts for TM; and Ainslie Meares and Pauline McKinnon as the experts for Stillness Meditation. Samples of their publications were selected that revealed their understandings of the meditation techniques and experiences. For Pearson, Rosenthal, and Roth, the sample comprised recent major works that appear to present their understandings in a consolidated form. For the other five experts it comprised publications selected by applying eligibility criteria to their full output. For the eight experts combined, 135 publications were selected (panel a). The second step was to review the selected publications and extract (i.e., copy) information about the techniques and experiences. As an example, panel (b) is an excerpt from one of the Shamatha texts (Wallace, 2006a, p. 13). The highlighted statement, “The faculty of mindfulness is crucial in shamatha practice”, describes a feature of the Shamatha technique (“Mindfulness”) and was therefore extracted. The third step was to place each extracted passage in an extraction table for the relevant practice and code it as indicating the relevant feature. To illustrate this, panel (c) is a simplified excerpt from the Shamatha extraction table. This excerpt relates to the “Mindfulness” feature of the Shamatha technique. The extracted statement “The faculty of mindfulness is crucial in shamatha practice” is coded “Mindfulness” by placing it in this section of the Shamatha table. As can be seen, this section of the table also includes the other extracted passages that have been coded “Mindfulness”

Representation of steps 4 and 5 in the evidence synthesis process. The fourth step was to describe the features of the techniques and interim-states fundamental in achieving the goal-states in each tradition, based on the relevant passages in the extraction table for that practice. The descriptions are provided in Sections 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 of this paper for Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation respectively. As the focus is on features fundamental in achieving the goal-states, the descriptions do not cover, for example, very fine details of the techniques, such as breath counting exercises that may be used as a temporary learning support at early stages of Shamatha (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 31–33). The fifth step was to compare the techniques and interim-states across the practices on select dimensions that stood out from the descriptions. The comparison is provided in Section 2.4. It is based on the understandings from the expert texts in Sections 2.1 to 2.3, but rather than simply taking the expert texts at face value, it also incorporates critical analysis where appropriate. The descriptions in Sections 2.1 to 2.3 and the comparison in Section 2.4 represent the results of the evidence synthesis. The passages in the extraction tables constitute the data

The Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation “extraction tables” referred to in Fig. 2 are in total 194 pages and are supplementary material in Woods et al. (2020). In this paper we will cite them using the shorthand SH, TM or SM together with the appropriate section number.

1.2 Order in which the features are described for each practice

For each practice, the order in which the features of the techniques and interim-states are described in Sections 2.1 to 2.3 is as follows. In the initial two or three subsections we describe the features of the technique, and related features of the interim-states, that appear to capture the essence of the practice. These are the features that most clearly distinguish the practice from other forms of meditation. We then provide further details on the interim-states, and describe the posture, recommended practice duration, and the ease, speed and frequency with which the goal-state/s are achieved. The only exception to this ordering is that we deal with posture towards the top of the Stillness Meditation section, on the basis that capturing the essence of that practice requires discussion of the posture.

2 Results

2.1 Shamatha

2.1.1 Three types of Shamatha practice

Wallace focuses on three types of Shamatha practice which he refers to as mindfulness of breathing, settling the mind in its natural state (“settling the mind”), and awareness of awareness (SH 1.2; Wallace, 2006a). Commonly meditators experience the awareness of awareness practice as the most subtle and challenging, and mindfulness of breathing as the most straightforward (Wallace, 2005, pp. 38–39, 2006a, p. 7). The main objective of the three practices is to develop exceptional stability and vividness of attention (Wallace, 1999a, p. 177, 2006a, p. 159).

2.1.2 Critical elements common to the three Shamatha practices

Stability, vividness, and relaxation

Stability, vividness, and relaxation are developed in “synergistic balance” (Wallace, 2012, p. 16), meaning that each increases in a gradual manner that supports the emergence of the others (SH 1.5.1; Wallace, 2011b, p. 139). Stability refers to the degree to which attention is sustained on the relevant meditation object or experience (SH 1.5.3; Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 187), and vividness concerns the clarity of attention (SH 1.5.4; Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 207). Wallace (1999a, p. 177) explains that, “[S]tability may be likened to mounting one’s telescope on a firm platform; while … vividness is like … polishing the lenses and bringing [it] into clear focus”.

Vividness has two aspects: temporal and qualitative (Wallace, 2011a, p. 156, b, p. 139, 2012/2014, pp. 131, 188). If the meditator has a high degree of temporal vividness, they can detect very brief movements or changes in the meditation object, and if they have a high degree of qualitative vividness, they can ascertain very fine or subtle details.

According to Wallace (2006a, p. 49, 2011a, p. 250), in normal life, focusing tends to be associated with a level of tension that leads to fatigue (SH 1.5.2). In the Shamatha practices, fatigue is avoided, since the increasing focus, and any effort that it requires, is accompanied by deepening relaxation (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 15, 49, 2011a, p. 250).

Mindfulness and introspection

The meditator develops attentional stability and vividness by cultivating mindfulness (Sanskrit: smrti) and introspection (Sanskrit: samprajanya) (SH 1.4.1; Wallace, 1999a, p. 178, 2010, p. 47). Wallace defines mindfulness as “attending continuously to a familiar object” (SH 1.4.2; Wallace, 2006a, p. 13) such that attention does not stray (p. 59). Introspection is the monitoring of the mind and/or body (SH 1.4.3; Wallace, 2006a, p. 65). It is principally concerned with assessing the quality of attention (Wallace, 2006a, p. 44, 2010, p. 47), but it also extends to checking the posture, and ensuring that all other aspects of the practice are being performed correctly (Wallace, 2010, pp. 47–48, 2011a, p. 58). In the Shamatha practices it must occur intermittently, rather than on a continuous basis (Wallace, 2010, p. 48). It is required more frequently in the earlier stages (Wallace, 2010, p. 48), and at advanced stages it is counterproductive and therefore given up (Wallace, 2001/2003, p. 133, 2010, p. 49, 2011a, p. 273).

Dealing with excitation and laxity

Excitation and laxity are attentional imbalances that lead to a loss of mindfulness (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 63). When excitation occurs the mind is said to be agitated or hyperactive, and therefore too easily attracted by other objects (SH 1.7.2; Wallace, 1999a, p. 176, 2011b, p. 184). In the case of laxity, attention loses its vividness, and this can cause it to decouple from the meditation object almost entirely (SH 1.7.3; Wallace, 2006a, p. 175, 2018, p. 217). Laxity is also described as dullness (Wallace, 2012, p. 161). Attention is unfocused or hazy, and the meditator can be spaced out, lethargic, daydreaming, and/or approaching drowsiness (Wallace, 2006a, p. 77, 2010, pp. 39, 42, 2012, pp. 13, 161, 2009/2014, p. 63).

The meditator detects excitation and laxity using introspection (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 63). If either is detected, they apply a remedy (SH 1.7.4; Wallace, 2006a, p. 44). The primary way to counteract excitation is to relax (Wallace, 2006a, p. 44). Attention has strayed from the meditation object, but rather than forcing it back, the meditator simply “release[s] the effort of clinging to the [distraction]” (Wallace, 2006a, p. 32), allowing attention to return (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 18, 32, 2010, pp. 34–35, 2009/2014, p. 73). The main way to counteract laxity is to arouse attention, by taking a fresh interest in the meditation object (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 44, 78, 2009/2014, p. 64). Doing this requires a small degree of tension and effort (Wallace, 2006a, p. 88, 2010, pp. 39, 62, 2009/2014, p. 64).

The aim with the remedies is to achieve the right “pitch” of attention, meaning the optimal balance between relaxation on the one hand, and arousal, tension and effort on the other (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 78, 88–89, 2007b, p. 60; Wallace & Wilhelm, 1993, p. 113). Being too relaxed tends to produce laxity, but being too aroused readily leads to excitation.

2.1.3 Key elements specific to each Shamatha practice

Mindfulness of breathing

In the mindfulness of breathing practice (SH 1.12), the meditation object is the sensations associated with breathing (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 6–7). The meditator takes no interest in other objects, such as other sense-perceptions or body-perceptions, or any thoughts, images or feelings.Footnote 1 If attention strays to those objects, the meditator simply releases them, and returns attention to the breath (Wallace, 2011a, p. 180, 2009/2014, p. 40). The breath is allowed to flow freely, with no effort being made to control it (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 17–20, 2011a, p. 180, 2012, pp. 9–11).

Settling the mind in its natural state

In the settling the mind practice (SH 1.13), the meditation object is the “space of the mind and whatever events arise within [it]” (Wallace, 2006a, p. 83). The space of the mind is the domain of mental events such as thoughts, images and feelings (Wallace, 2011b, pp. x, 116). It does not include sense-perceptions or body-perceptions (Wallace, 2011a, p. 190, b, p. 132).

In this practice, mental events are attended to – or watched – as they arise and then pass (Wallace, 1999a, p. 184). The critical instruction is that there should not be distraction or grasping (Wallace, 2006a, p. 83, 2011a, p. 159, b, p. 132). Any distraction or grasping should therefore be identified using introspection, and then simply released (Wallace, 2011a, p. 158, 2009/2014, p. 50). One aspect of the instruction to avoid distraction and grasping is that the meditator should take no interest in sense-perceptions or body-perceptions, and if attention strays to them it should be returned to the mental events (Wallace, 2006a, p. 83, 2011a, p. 190), or, if no mental events can be detected, to the empty space of the mind (Wallace, 2006a, p. 92). Another element is that the mental events should be allowed to arise and pass freely, without any attempt to control them (Wallace, 2006a, p. 83, 2011b, p. 116).

A third aspect is that the meditator should attend to the mental events as mental events, rather than being carried away by their contents (Wallace, 2006a, p. 83, 2012/2014, pp. 185–186, 2009/2014, p. 49, 2018, p. 6). For example, if the meditator has the thought of a meeting with someone from earlier in the day, they should attend to that thought as a thought, rather than becoming wholly immersed in the circumstances of the meeting (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 49). Becoming absorbed in the contents of the mental event would amount to mind-wandering, and mind-wandering is to be eliminated in Shamatha practice (Wallace, 2011a, p. 267, b, p. 116, 2009/2014, p. 49). In settling the mind meditation, attention moves from one mental event to another as each arises and passes. From the Shamatha perspective that does not constitute mind-wandering, provided that the meditator maintains attention on the mental events as mental events.

Awareness of awareness

In the awareness of awareness practice (SH 1.14), the meditation object is awareness itself (Wallace, 2006a, p. 132). Awareness itself is an “extremely subtle” object (Wallace, 2010, p. 80), and from an experiential point of view it can seem as if there is no object at all (Wallace, 2006a, p. 132). The meditator takes no interest in sense-perceptions, body-perceptions or mental events (Wallace, 2011a, pp. 226, 249, 2012/2014, p. 66). If attention strays to them, they are simply released (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 133–134, 2011a, p. 226, 2009/2014, pp. 72–73). Unlike the other two Shamatha practices, “attention is not directed to anything” (Wallace, 2006a, p. 132). By taking no interest in the other objects, and by otherwise dealing with excitation and laxity, attention is simply allowed to rest in awareness itself (Wallace, 2005, p. 35, 2006a, pp. 132–134).

2.1.4 The 10 stages of attentional development

Wallace describes 10 stages of attentional development in Shamatha practice based on the text Stages of Meditation by the eighth century Buddhist contemplative Kamalashila (SH 1.2, 1.11; Wallace, 2006a, p. 5). The meditator advances through the stages by counteracting forms of excitation and laxity that are initially coarse but become increasingly subtle (SH 1.2, 1.7; Wallace, 2006a, p. 6).

Any one of the three practices can be used for all 10 stages, or the meditator can switch between the practices at different points (Wallace, 2006a, p. 7). Wallace recommends using mindfulness of breathing for stages 1 to 4, settling the mind for stages 5 to 7, and awareness of awareness for stages 8 onwards (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 6–7, 79–80). In this paper we focus on that recommended sequence, rather than the alternative approaches.

The meditator begins with the mindfulness of breathing practice. The main emphasis at stage 1 is relaxation, and from that a degree of attentional stability emerges (Wallace, 2006a, p. 33, 2011a, p. 139). Stage 1 is achieved when the meditator can attend to the meditation object for 2 or 3 seconds (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 13, 22).

The second and third stages are focused on developing stability (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 29–31, 43–44, 2010, pp. 60–61). As that occurs, the experience becomes calmer and more pleasant (Wallace, 2010, p. 61). Upon reaching stage 4, the meditator is free of coarse excitation, meaning that attention always remains on the meditation object to some degree (Wallace, 2006a, p. 59). The emphasis at stage 4 is on increasing vividness by dealing with coarse laxity (Wallace, 2010, p. 62). Over stages 5 to 9, the remaining, more subtle forms of excitation and laxity are overcome (Wallace, 2006a).

At stage 5, the meditator switches to the settling the mind practice. As they learn to release distractions and grasping, they develop a clear sense of stillness and movement (Wallace, 2006a, p. 92, 2012/2014, p. 186). Mental events arise and pass, creating the sense of movement, but the watching awareness is no longer pulled about by them due to grasping, and it therefore remains still (Wallace, 2005, p. 27, 2011b, p. 149, 2009/2014, pp. 49–50). The mental events gradually become calmer and begin to peter out (Wallace, 2011b, pp. 118–119). By stage 6, thoughts are infrequent and the senses are largely withdrawn (Wallace, 2010, p. 64; Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 211).

At stage 8, the meditator moves to the awareness of awareness practice. Upon achieving that stage, attention is highly focused, and free from excitation and laxity for long periods (Wallace, 2006a, p. 131). Since in approaching stage 10 there is no need for introspection or counteracting excitation and laxity, virtually no effort or doing is required (Wallace, 1998/2005, p. 187, 2006a, pp. 131, 137, 2010, p. 66).

At the 10th and final stage, the meditator releases the meditation object (SH 2.14.24). Body and mind undergo a radical transition, becoming exceptionally fit or pliant, and an intense bliss is experienced, which then subsides (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 155–156). The meditator has then achieved the goal-state.

2.1.5 Posture

The posture for the Shamatha practices should be comfortable and permit a sense of ease (SH 1.21; Wallace, 2005, p. 13, 2011a, p. 29, 2009/2014, p. 47). Two main types are recommended: sitting (cross-legged or on a chair), and lying in the supine position (Wallace, 2011a, p. 32). Sitting counteracts laxity, eliciting vividness, while lying counteracts excitation, encouraging relaxation (Wallace, 2011a, p. 245).

When sitting, the meditator is upright, with their back straight but not rigid, and the sternum slightly lifted (Wallace, 2005, pp. 13–14, 2009/2014, p. 47). Slouching is avoided (Wallace, 2005, p. 14). All postures should “reflect a sense of vigilance”, as opposed to “just collapsing into drowsiness” (Wallace, 2005, p. 13; see further Section 2.4.6 below). For mindfulness of breathing, eyes may be open or closed, but for the other two practices they should be at least partially open (Wallace, 2011a, p. 248).

2.1.6 Practice duration

When the meditator first starts to practise, their meditation sessions should be 24 minutes (SH 1.22; Wallace, 2006a, p. 9, 2011a, p. 33). As they progress, they can increase the duration, subject to the need to maintain quality of practice (Wallace, 2006a, p. 64, 2009/2014, p. 73). If they are practising as part of an active life, rather than having withdrawn into a retreat context, in most cases more than 2 hours per day of practice will be needed to pass stage 3 (Wallace, 2006a, p. 8).

2.1.7 Ease, speed and frequency with which the goal-state is achieved

Wallace describes Shamatha practice as “extremely demanding” (Wallace, 2007b, p. 43; see, similarly, Wallace, 1998/2005, p. 220, 2012/2014, p. 185). One reason for this is that it requires effort, and that effort must be applied in a skilful manner (SH 1.10). The meditator cultivates relaxation from the beginning of the practice, but effort is also required up until advanced stages. A second reason Shamatha is demanding is that progressing to the goal-state requires 6 to 12 hours of practice per day (Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 156) over a period of months or years (Wallace, 2006a, p. 143). A third reason is that the practice will be effective in leading the meditator to the goal-state only if a number of supporting conditions are satisfied (SH 1.23). These conditions are generally taken to include that the meditator practises in a retreat environment, with little or no socializing or entertainment between meditation sessions. The full set of conditions, which includes various mental prerequisites, is itself highly demanding (Wallace, 2011b, pp. ix–x, 2012/2014, pp. 154–156, 185, 2018, p. 194). Progressing past stage 4 of the 10 stages of attentional development necessitates a “vocational commitment” to the practice (Wallace, 2006a, p. 8), which typically includes full-time hours, and withdrawal from active life (pp. 8, 45, 49–50).

It is suggested by Wallace that approximately 5,000 to 10,000 hours of practice may be required to achieve the goal-state (Wallace, 2006a, p. 162; Wallace & Hodel, 2008, pp. 207–208). However, this guideline assumes that at least the major supporting conditions are satisfied (SH 1.23; Wallace, 2006a, p. 162, 2007b, pp. 42–43, 2010, pp. 81–82, 2012/2014, p. 156), and in the modern world that is rarely the case (Wallace, 2011b, p. x, 2012/2014, pp. 154–156). Wallace explains that, consequently, achieving the goal-state is “exceptionally rare” (Wallace, 1998/2005, p. 219, 2006a, p. 147), even among practitioners in or exiled from Tibet (Wallace, 2001/2003, p. 97, 1998/2005, p. 219, 2010, p. 82, 2012/2014, p. 148). He indicates that it is not yet known whether non-Tibetan meditators living in western countries can achieve the goal-state or how long that would take (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 162–163, 2009/2014, pp. 114–115). Wallace considers that one reason the Shamatha goal-state is not achieved more frequently is that meditators are often attracted to less onerous or more advanced practices, and therefore fail to give Shamatha the commitment it requires (SH 1.23). His belief is that, if meditators were to make that commitment, and the supporting conditions could be satisfied, achieving the goal-state/s would be “very feasible” (Wallace, 2010, p. 83), and might therefore no longer be rare (pp. 66, 83).

2.2 Transcendental Meditation

2.2.1 Use of mantra

In TM, the meditator repeats a mantra silently in their mind (TM 1.4.1; Roth, 2018, p. 2; Shear, 2006b, p. xvi), and that involves bringing attention to the mantra (Shear, 2004, p. 86, 2006b, p. xvi, 2011a, p. 156). The mantras are words or sounds that have no meaning for the meditator (Rosenthal, 2011/2012, pp. 16, 279; Roth, 2018, p. 2). A specific mantra is selected for the meditator by their TM teacher (TM 1.5.3; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 16; Roth, 2018, p. 57). To be effective, the mantra must be repeated in the proper way (Shear, 1990b, p. 101; Shear & Jevning, 1999a). That means the repetition must be effortless, and involve no concentration or control (TM 1.6; Faber et al., 2017; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 16; Roth, 2018, pp. 35, 57; Shear, 1990b, p. 101). The TM experts tend to use the term concentration interchangeably with the term focus (e.g., Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 160; Travis & Shear, 2010a).

2.2.2 Absence of effort, concentration and control

The absence of effort, concentration and control is said to be a feature of both the repetition of the mantra, and TM as a whole (TM 1.6; Pearson, 2013, p. 29; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 18; Roth, 2018, p. 29; Travis & Shear, 2010a). From the expert texts we have identified four main aspects of this understanding.

The first aspect is that the repetition of the mantra should not be performed in a manner that is strained or forced (Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 26; Roth, 2018, p. 61). Using force to exclude mental content such as thoughts, perceptions or images is not part of the practice (Pearson, 2013, p. 394; Roth, 2018, p. 2; Travis & Parim, 2017). The second aspect is that the meditator should not be concerned with any ongoing mental content of this kind (Shear & Jevning, 1999a; Travis & Parim, 2017). Such content may be present alongside the mantra, or the meditator may lose awareness of the mantra and experience that content alone. The third aspect is that the meditator is not instructed to monitor their attention. However, if they happen to notice that they have lost awareness of the mantra and are experiencing the other content, they should gently return to the mantra (Faber et al., 2017; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 219; Travis & Shear, 2010a, p. 1116).

The fourth aspect is given particular emphasis by all five experts: Repeating the mantra initiates an automatic movement of the mind towards the goal-state (TM 1.6; Pearson, 2013, pp. 395–396; Roth, 2018, pp. 32–35; Shear & Jevning, 1999a; Travis & Shear, 2010a). Movement in that direction, and the achievement of the goal-state, are referred to as transcending (TM 2.1; Faber et al., 2017, p. 307). The TM experts rely on a diving analogy: Repeating the mantra is like leaning over the edge of a pool – the movement downwards then just happens automatically (Pearson, 2013, p. 396; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 278). Once transcending has commenced, it will be halted or impeded by applying any effort or control (Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 262; Shear, 2006c, 2011b; Travis, 2011, 2014). Since the process is automatic, the practitioner has a sense of “just letting the mantra happen” (Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 218, quoting a meditator).

2.2.3 Further details on the interim-states

In the course of transcending, thoughts and other mental content settle down (TM 1.8.1; Pearson, 2013, pp. 45, 52, 395; Roth, 2018, p. 17; Shear, 1996b, 1995/1997b). Thoughts gradually become less prominent in awareness and reduce in frequency, disturbing the meditator less and less (Pearson, 2013, pp. 47, 52, 395; Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 26; Travis et al., 2005). The mantra also becomes less prominent (Travis & Shear, 2010a; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 288), and there is a growing sense of relaxation and calm (Roth, 2018, p. 152).

A TM session is said to involve repeated cycling as follows:

-

The meditator repeats the mantra and transcends fully or to some extent;

-

They cease transcending, and then notice that they have lost awareness of the mantra; and

-

They return to the mantra and the next cycle begins (Faber et al., 2017; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, pp. 18–19, 2016/2017, pp. 46, 217; Travis, 2011; Travis & Parim, 2017).

The second stage, where the meditator ceases transcending, will occur even if they are practising correctly, and there is nothing they can do within the meditation session to stop it occurring. It is therefore considered an integral part of the process (Faber et al., 2017; Roth, 2018, p. 32; Travis & Parim, 2017).

If the meditator is transcending but has only done so to some extent, that means they have not reached the goal-state. They will still have awareness of the mantra, but if they lose that awareness prior to reaching the goal-state then they cease to transcend (TM 2.7.28; Faber et al., 2017; Travis & Parim, 2017). If the meditator has fully transcended, that means they have attained the goal-state. In the goal-state they have no awareness of the mantra, and no content such as thoughts, perceptions and images (TM 2.7.14–2.7.21, 2.7.28; Travis & Shear, 2010a). In this scenario, the meditator ceases to be fully transcended, meaning they exit the goal-state, when content such as thoughts, perceptions and images resumes. If at that point the meditator does not also have awareness of the mantra, they will have ceased transcending at all.

Shear refers to pure individuality and pure bliss as highly abstract stages that immediately precede the goal-state (TM 1.8.2; Shear, 2011a). However, he notes that meditators may simply move through them without noticing them, particularly if they are beginners (Shear, 2011a). Those stages are not discussed by the other TM experts.

2.2.4 Posture

TM is conducted in a comfortable seated posture, typically using a chair (Pearson, 2013, p. 29; Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 22; Roth, 2018, pp. 2, 58). Roth (2018, pp. 2, 58) advises that any seated position is acceptable. There is no instruction for the back to be straight, or that any other discipline in the posture – such as an absence of slouching – is required. TM is performed with eyes closed (Pearson, 2013, p. 29; Roth, 2018, p. 30).

2.2.5 Practice duration

The recommended TM practice is 15 to 20 minutes twice a day (Pearson, 2013, p. 394; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 276; Shear, 2006c).

2.2.6 Ease, speed and frequency with which the goal-state is achieved

In TM it is implied that it is usual, rather than rare, for meditators to access the goal-state, provided they maintain their practice (TM 2.6). The practice is said to be easy and pleasant (TM 1.2–1.3), and intensive hours are not required (see Section 2.2.5). There are no demanding supporting conditions or prerequisites, and it is assumed that the meditator will be practising as part of an active life, rather than in a retreat environment (TM 1.5.6). Meditators take different lengths of time to first access the goal-state. For some people it occurs in the first session or week, while for others it takes longer (Pearson, 2013, p. 29; Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 36; Shear, 2006c, p. 25, 2011b, p. 53). The TM experts state or imply that for most meditators it happens within 3 months (TM 1.5.2, 2.6; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, pp. 42–43; Shear & Jevning, 1999a, p. 197; Travis, 2006, p. 24).

2.3 Stillness Meditation

2.3.1 The pairing of control and relinquishment of control

Meares and McKinnon each present Stillness Meditation in a range of ways (SM 1.6, 1.8, 1.10–1.12). Careful consideration of the various presentations indicates that the practice can be summarized as follows: The meditator adopts a posture of initial minor discomfort, and then gives up the effort of doing anything beyond maintaining that posture. This formulation captures the dynamic central to the practice: the pairing of control and the relinquishment of control (Meares, 1978/1986, 1987a, p. 47). The control is required to maintain the posture, and the relinquishment occurs in giving the mind free reign (Meares, 1978/1986).

2.3.2 Control – maintenance of the posture

The practice is performed with eyes closed (Meares, 1967/1968, p. 90). The posture of the meditator must produce an initial minor discomfort (SM 1.10). At the beginning of the meditation session there is therefore a slight difficulty in maintaining it, and a small element of deliberate control is required (SM 1.11–1.12; Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 34, 37). As the session progresses, the meditator relaxes (see Section 2.3.4). They lose awareness of – or transcend – the discomfort (SM 1.10). The body comes to simply remain in the correct posture (SM 1.11.4, 1.12). That entails a degree of postural control, but the deliberate element of that control is no longer necessary, and maintenance of the posture is then experienced as effortless.

McKinnon (2011, pp. 67, 102–103) considers that sitting in a straight-backed chair is sufficient to provide the initial slight discomfort (SM 1.11). The meditator sits with their back, neck and head upright, but balanced, poised and at ease, rather than slouched or strained. Meares (1978/1986, p. 36) viewed this posture as suitable for meditators at early stages of practice (SM 1.11.4). However, he thought that the meditator should progress to more advanced postures as they became more experienced, in order to ensure that the posture continued to produce an initial slight discomfort (SM 1.11). McKinnon (2011, pp. 102–103, 1983/2016, pp. 271–272) views the advanced postures as unnecessary (SM 1.11.1). She considers that the basic posture is sufficient to provide the initial discomfort for meditators at any level of experience.

The Stillness Meditation accounts do not include any instruction for the meditator to monitor their mind or body. For beginners, there is the possibility that the body will move out of the correct position, either before or after the meditator has relinquished the deliberate postural control (see above). Meares (1978/1986, p. 37) indicates that in this scenario the meditator should correct the posture, and that the problem will then soon cease. Neither Meares nor McKinnon advise as to whether the meditator may engage in monitoring to gauge whether the body has moved from the correct position. It is therefore not clear whether monitoring is permitted, or whether the meditator should only correct the posture if they happen to notice that the movement has occurred. If monitoring is permitted, it would need to be intermittent, rather than continuous. Continuous monitoring would be inconsistent with the emphasis on non-doing (see below).

2.3.3 Relinquishment of control – giving the mind free reign

The practice is said to involve the relinquishment of all control other than that required to maintain the posture (SM 1.8–1.9, 1.12; McKinnon, 2002/2008, p. 15, 2011, 1983/2016; Meares, 1973b, p. 254, 1984, p. 18, 1976/1984, p. 21, 1978/1986, 1989, pp. 116–117). Remaining in the correct posture, the meditator gives up the effort of doing anything: They do not need to try, or to otherwise execute any instruction or action. One aspect of this is that they do not need to maintain attention on a meditation object or repeat a mantra. In fact they give up the effort of maintaining any particular attention or awareness. The mind is given free reign, allowing it to wander where it will. On this basis, the practice is said to be effortless (SM 1.8). As there is no need for doing beyond maintaining the posture, there is no need for control or effort associated with such doing. As noted above, the meditator soon finds that their body simply remains in the correct position. From that point there is no deliberate doing, or associated control or effort, with respect to the posture.Footnote 2

McKinnon (2011, 1983/2016) states that the practice involves no “technique”, on the basis that there is no need for doing, as described above (SM 1.8). If the meditator, properly seated, was to ask, “What should I do to practise correctly?”, an acceptable reply would be “You don’t need to do anything” (McKinnon, 2011, p. 78; Meares, 1978/1986, p. 153). While in this sense it seems true that there is an absence of technique, the practice can be characterized as involving technique when considered at a broader level. For example, the meditator is required to assume and maintain a particular posture, and to relinquish the effort of doing anything further. If they fail to adopt the posture, or to relinquish effort, they could be said to be practising incorrectly (SM 1.11; Meares, 1977a, p. 133, 1978/1986, pp. 46–47). From the broader perspective that would constitute a failure of technique.

2.3.4 Further details on the interim-states

When the meditator first sits down, they may be quite aware of their thoughts, things happening around them, and the slight discomfort of the posture (McKinnon, 1991, pp. 73, 77, 2011, pp. 76–77, 84). As they practise relinquishing the effort of doing, their body begins to relax and the physical relaxation gradually deepens (McKinnon, 1991, pp. 76–77; Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 9–10). The mind is allowed to wander freely, which leads to thoughts becoming less logical and more abstract, and with the physical relaxation the intensity and frequency of thoughts reduces (SM 1.9, 1.14, 1.15.2; Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 24–25). The meditator also becomes less aware of the things happening around them, and loses their awareness of the slight discomfort in the posture (SM 1.10, 1.14). With awareness now disturbed less by thoughts, the surrounding environment, and the posture, the meditator experiences a growing sense of mental relaxation, calm and ease (SM 1.6, 1.14; Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 24–27).

In the initial period of learning the practice, meditators may experience anxiety, or feelings such as boredom and discomfort, arising from their not yet being accustomed to the experience of non-doing (SM 1.14, 1.15.3). McKinnon (1983/2016, p. 191), for example, refers to the “anxiety that welled up within [her] at intervals” when she commenced the practice, and “the eerie absence of any kind of stimulus”. Once the meditator becomes accustomed to the non-doing, any negative feelings such as these will pass.

2.3.5 Practice duration

The usual recommendation is to practise 10 to 20 minutes twice a day (McKinnon, 2011, pp. 107, 232, 1983/2016, p. 269; Meares, 1967/1968, p. 71, 1978/1986, pp. x, 46). A longer duration may be appropriate if the meditator is seeking to deal with particularly stressful circumstances or recover from certain mental conditions (McKinnon, 1983/2016, pp. 213, 270).

2.3.6 Ease, speed and frequency with which the goal-states are achieved

The Stillness Meditation accounts imply that, if meditators keep up their practice, they can expect to gain access to the goal-states (SM 2.2). Once the meditator achieves an initial familiarity with the practice, it is said to be easy and pleasant (SM 1.3–1.4). There is no need for a retreat environment (McKinnon, 1991, p. 71) or intensive hours (see Section 2.3.5), and there are no other demanding preconditions. Individuals vary in terms of how long it takes to first access the goal-states. Some achieve it in the first session or week (McKinnon, 2011, pp. 101–102; Meares, 1973a, p. 734, 1988, p. 26), some within a few weeks or months (McKinnon, 2011, pp. 168, 176), and for others it takes longer. McKinnon (1983/2016, p. 217) notes that for some people it may take “quite a long time”, and that it may be 2 years before the experience is “deep and fulfilling”.

2.4 Comparison across the practices

In Sections 2.4.1 to 2.4.7 we provide a detailed comparison of the techniques and interim-states across the three practices on key dimensions. The dimensions are distinct from one another but there is a degree of overlap. The comparison is based on the understandings from the expert texts set out in Sections 2.1 to 2.3, but rather than merely taking the expert texts at face value, we also apply critical analysis where appropriate.

Table 1 lists the dimensions and summarizes our conclusions for each practice. The dimensions are either graded (e.g., None to Very high) or binary (Yes/No).Footnote 3 Figures 4 and 5 are charts which together display our conclusions for the 10 graded dimensions for which there are appreciable differences across the practices. Figure 4 deals with the two dimensions specifically relating to posture, and Fig. 5 covers the other eight.

Conclusions for the two graded dimensions which specifically relate to posture and for which there are appreciable differences across the practices. For both dimensions, 0 = None, 3 = Low, 6 = Medium, 9 = High. In this Fig. 4 and in Fig. 5, where the rating in Table 1 is a range (e.g., None/Low) rather than a single level (e.g., None), the midpoint of that range is used

Conclusions for the other eight graded dimensions for which there are appreciable differences across the practices. For the dimension “Ease with which goal-state/s achieved”, 3 = Difficult, 6 = Medium, 9 = Easy. For the dimension “Speed with which goal-state/s achieved”, 3 = Slow, 6 = Medium, 9 = Fast. For the remaining six dimensions, 0 = None, 3 = Low, 6 = Medium, 9 = High

2.4.1 Use of meditation object

Shamatha and TM involve meditation objects, whereas Stillness Meditation does not (Sections 2.1.2, 2.1.3, 2.2.1, 2.3.3).

2.4.2 Stability/vividness and focusing of attention

Within the interim-states, the Shamatha meditator aims for exceptionally stable and vivid attention on the meditation object (Sections 2.1.1, 2.1.2).Footnote 4 To achieve that, they must cultivate mindfulness and introspection, and detect and counteract various forms of excitation and laxity (Section 2.1.2). That is done through careful and systematic steps carried out across the various stages of attentional development (Section 2.1.4). Mindfulness is defined as continuously attending to – or focusing on – the object (Section 2.1.2). With practice, the meditator develops an extremely high level of focus (Section 2.1.4).

By deliberately repeating the mantra, the TM meditator brings their attention to it (Section 2.2.1). The repetition is said to initiate the movement of the mind towards the goal-state (Section 2.2.2). The TM experts present TM as involving no focus (Section 2.2.2), but it seems that at least some degree of focus is involved in bringing attention to the mantra. The main reason the experts say that there is no focus is that, once the movement towards the goal-state has been initiated, it is said to be automatic (Section 2.2.2). Since the movement is automatic, unless it ceases spontaneously no further deliberate bringing of attention to the mantra is required in order to progress to the goal-state (Sections 2.2.2, 2.2.3).Footnote 5

For the mind to move towards the goal-state, the mantra must remain in awareness (Section 2.2.3). The TM experts do not see this as involving focus, whether deliberate or otherwise. Their understanding seems to be that, as the meditator moves automatically towards the goal-state, the mantra is within awareness, but the meditator is not focused on it (Travis & Parim, 2017). They make clear that it is fine for other mental content such as thoughts, perceptions and images to be present at the same time (Section 2.2.2).

The experts tend not to suggest that TM leads to any kind of stability or vividness of attention on the mantra. The aim is simply to use the mantra to get to the goal-state, rather than cultivating those qualities. If stability was being cultivated, that might suggest that there was something the meditator could do within a meditation session to reduce the occasions that the mantra left their awareness. In TM it is indicated that there is nothing the meditator can do in this regard, meaning that the loss of awareness – which halts the automatic movement towards the goal-state – will occur, at times, even if the meditator is highly experienced (Section 2.2.3). In Shamatha, vividness of attention on the meditation object increases as the meditator moves towards the goal-state. In TM, on the other hand, the mantra is said to grow progressively less prominent in awareness (Section 2.2.3).

Although stability and vividness with respect to the mantra are not emphasized in TM, it may go too far to say that they are not present or cultivated at all. It seems that some small degree of stability and vividness may be involved in bringing attention to the mantra, and its remaining in awareness.

In Stillness Meditation, there is no meditation object, and the meditator makes no effort to direct or maintain attention (Section 2.3.3). As such, there is no focusing, and no steps to cultivate stability or vividness with respect to an object.

2.4.3 Tolerance of mind-wandering

In Shamatha, mind-wandering is taken to occur when attention strays from the meditation object in full or in part.Footnote 6 For example, in the mindfulness of breathing practice, the object is the sensations associated with breathing (Section 2.1.3). If the meditator starts thinking about what they will do after the meditation session, attention has strayed from the object. In the Shamatha tradition the mind is taken to have wandered.

The TM meditator can have thoughts alongside the mantra, or when they have lost awareness of the mantra prior to reaching the goal-state (Section 2.2.2). The TM texts do not provide a clear picture as to whether these thoughts are regarded as mind-wandering within the TM tradition (cf. Rosenthal, 2016/2017, pp. 158–163; Roth, 2018, p. 32).

In Stillness Meditation, the mind is given free reign (Section 2.3.3). The meditator relinquishes control except as required to maintain the posture. Thoughts are allowed to arise and change, and within the tradition this is treated as mind-wandering.

In the academic literature, there are different definitions of mind-wandering (Christoff et al., 2018; Mills et al., 2018; Seli et al., 2018a, b). The Shamatha conception closely aligns with the definition of mind-wandering as task-unrelated thought – i.e., thoughts unrelated to an ongoing task (Smallwood & Schooler, 2006). Taking the example above, the meditator’s thoughts of what they will do after the meditation session are unrelated to the task of attending to the meditation object. The Stillness Meditation conception aligns more closely with the definition of mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: thoughts that arise and change with relative freedom due to an absence of deliberate control or other strong constraints (Christoff et al., 2016, 2018; Irving, 2016; Stan & Christoff, 2018).

In this section we wish to compare the degree to which mind-wandering is tolerated in the three practices. If mind-wandering is defined as task-unrelated thought, the comparison would not be very informative. In the TM tradition, the thoughts alongside the mantra and where the mantra is lost (see above) are not regarded as off-task, because they are considered an integral part of the TM process (Faber et al., 2017). Based on this understanding, in TM there is no mind-wandering in the sense of task-unrelated thought.

In Stillness Meditation, the task could be defined broadly as relinquishing control other than that required to maintain the posture. In this case, any thoughts that arise when the meditator is practising correctly would not be off-task, because they are simply what happens, on the path to the goal-states, when the meditator relinquishes control. As in TM, there would be no mind-wandering in the form of task-unrelated thought.

Relinquishing control in Stillness Meditation is about non-doing – i.e., giving up doing. If task is defined narrowly as something that the meditator has to do, there is no task in Stillness Meditation (other than maintaining the posture). Here the definition of mind-wandering as task-unrelated thought is not really applicable.

If we instead define mind-wandering as spontaneous thought, mind-wandering can be readily identified in all three practices, and the cross-practice comparison is more intuitive and informative. This is the approach that we will take in the remainder of this paper.

The thoughts that may arise in Shamatha when attention strays from the meditation object are not all spontaneous, and therefore not all mind-wandering in the sense of spontaneous thought. The meditator may be, for example, thinking quite rigidly and methodically about what they will do after the meditation session, as opposed to their mind hopping freely and easily from thought to thought. Spontaneous thoughts are just one type of thought that may occur when attention strays from the object. In TM and Stillness Meditation it is similar: Spontaneous thoughts are just one type of thought that may occur. As an example, the Stillness Meditation practitioner may also find themselves thinking rigidly and methodically about what they will do after the session. They then simply give up the effort of doing anything: They give up any effort in thinking in this rigid and methodical manner, and they give up any effort to stop thinking this way. By relinquishing this effort, in time the mind begins to move more freely.

To what degree do the three practices tolerate mind-wandering in the sense of spontaneous thought? In Shamatha, the aim is to eliminate any straying from the meditation object, and thinking (whether spontaneous or otherwise) is a form of straying.Footnote 7 At a very advanced stage, attention becomes so highly focused on the object that it does not stray at all. Up until that stage it is accepted that attention will stray to some degree. In the early stages, it will frequently leave the object entirely, whereas in the middle and later stages it will do so only in part (Sections 2.1.2, 2.1.4). The straying of attention occurs due to excitation and laxity. The meditator detects them using introspection (monitoring), and then applies appropriate remedies, which allow attention to return to the object.

In TM there is a greater tolerance of spontaneous thought. The meditator is not concerned with thoughts, provided that they still have some awareness of the mantra (Section 2.2.2). In contrast with Shamatha, the meditator is not advised to monitor their attention (Section 2.2.2). However, if they happen to notice that they have lost awareness of the mantra entirely, they are instructed to gently return to it. It is accepted that this will occur numerous times in a meditation session (Section 2.2.3).

Eifring (2018, pp. 529, 537), writing from outside the TM tradition, indicates that TM “accepts thoughts without reservations” (p. 537). It is evident, however, from the understandings above, that spontaneous and other thoughts are only accepted to some degree. The limitations on spontaneous thoughts in TM can be better appreciated by comparison with Stillness Meditation. In that practice, there are no qualifications with respect to the acceptance of spontaneous thought. In particular, and in contrast to Shamatha and TM, there is no meditation object. As such, no question arises as to whether the meditator’s awareness has strayed from an object, and there is no need to bring awareness back to one.

2.4.4 Fading content, and calm/relaxation

In each practice, mental content such as thoughts, perceptions, and images gradually settles and fades, as the meditator moves towards the goal-state/s (Sections 2.1.4, 2.2.3, 2.3.4). The meditator also experiences a growing sense of calm and relaxation (Sections 2.1.2, 2.1.4, 2.2.3, 2.3.4).

2.4.5 Introspection/monitoring

In this paper we are using the term introspection as it is defined by Wallace: It is the monitoring of the mind and/or body (Section 2.1.2). Monitoring is a key facet of Shamatha practice. Its main role is to gauge whether and to what extent attention is focused on the meditation object, and to assess the degree of vividness. It is also used to ensure that the practice is otherwise being undertaken correctly, which includes maintaining the appropriate posture. The monitoring is intermittent, and at advanced stages it is counterproductive and therefore abandoned.

In TM and Stillness Meditation there is no instruction for the meditator to engage in monitoring. If the TM practitioner happens to notice that they have lost awareness of the mantra, they return to it. It is not suggested, though, that they actively monitor their awareness. The TM organization has explicitly stated that the practice does not involve monitoring (Maharishi Foundation USA, 2018; see also Travis & Parim, 2017).

In general, deliberate monitoring seems incompatible with Stillness Meditation. That is because in that practice the meditator relinquishes all deliberate doing soon after commencing a meditation session (Section 2.3.3). One area where monitoring may be permitted is the identification of movement out of the correct posture by beginner meditators (Section 2.3.2). It is not clear from the Stillness Meditation texts whether monitoring is allowed in that context. If monitoring is allowed, it would be intermittent rather than continuous (Section 2.3.2), and since the posture can be quickly stabilized, very little would be required.

Although it is not spoken about by the TM or Stillness Meditation experts, it seems likely that beginner meditators in those practices would engage in a small degree of monitoring. Those meditators will have been instructed as to what is required in order to practise correctly, and it seems unrealistic to think that during the early sessions they would not occasionally check their practice against the instructions. TM meditators may wish to check, for example, that their posture is comfortable, and that they are repeating the mantra in an unforced manner (Sections 2.2.2, 2.2.4). Stillness Meditation practitioners might check that their posture is correct, and that, besides maintaining the posture, they are giving up the effort of doing anything (Section 2.3.3).Footnote 8 It also seems plausible that experienced meditators in the two practices might engage in a similar, but more subtle and abbreviated, form of monitoring right at the beginning of a meditation session.

2.4.6 Deliberate doing/control and associated effort

In cognitive science it is understood that control refers to the guiding of mental or physical experience or action (Christoff et al., 2016; Markovic & Thompson, 2016), and that it can be deliberate or automatic (Lutz et al., 2015). Effort refers to the degree to which something is experienced as difficult, as opposed to easy (Lutz et al., 2015; Stan & Christoff, 2018). The expert texts analyzed in this paper rely on the constructs control and effort, but the experts tend not to formally define them. To facilitate discussion we will therefore employ the cognitive science understandings above, while at the same time explaining the particular ways in which the constructs are applied in the expert texts.

A degree of control is required whenever the meditator is doing something, so we will often refer to “doing/control”. In Stillness Meditation a clear distinction is drawn between doing/control associated with the posture, and other forms of doing/control. In this section we compare the deliberate doing/control and associated effort across the three practices, and we will also draw that distinction. We will first consider the postural elements, and we will then turn to the other aspects.

Postural aspects

In Shamatha the main postures are sitting (on a chair or cross-legged), and lying down (Section 2.1.5). The typical posture in TM and the basic posture in Stillness Meditation is sitting on a chair (Sections 2.2.4, 2.3.2). We will confine our discussion to the meditator sitting on a chair with their back supported by it, as that is a key posture in all three practices, and focusing on it enables easier comparison.

The posture in each practice involves some level of doing/control. In simply sitting on a chair, the meditator must maintain some muscle tone in the torso, back and neck muscles. As Meares (1989, p. 125) points out, if they did not then they would collapse like a jellyfish. The Shamatha posture is very similar to the posture in Stillness Meditation. In those two practices the body is at ease rather than strained, but it must also be poised, rather than slouched. Wallace refers to this as a posture reflecting vigilance as opposed to collapsing (Section 2.1.5), and Meares (1978/1986, p. 34) and McKinnon (2002/2008, p. 36) talk about it as an easy discipline or control. It seems that this element of bodily poise or discipline is not required in TM (Section 2.2.4). Shamatha and Stillness Meditation therefore appear to involve an additional level of bodily doing/control.

In Shamatha and Stillness Meditation the poise or discipline is virtually identical, but it is labelled differently. In Stillness Meditation it is referred to as initial slight discomfort, whereas in Shamatha it is not. In Shamatha the posture is referred to as comfortable, on the basis that the body is at ease, and any discomfort is only slight.

At the beginning of a Stillness Meditation session, a small deliberate element of doing/control is required for the posture (Section 2.3.2). Since Shamatha involves a very similar posture, one would expect that the deliberate element would be required in that practice too. Without deliberate doing/control, the meditator in each practice would likely slouch to some degree. Lutz et al. (2015) indicate that deliberate control entails a degree of effort. On that basis, the Shamatha and Stillness Meditation practitioners would experience some sense of effort associated with the posture at the beginning of the session. Since the TM posture does not require the same bodily poise or discipline (see above), the deliberate element of doing/control, and associated effort, would likely also be reduced. Depending on the degree of slouching in the posture, it may even be that no deliberate doing/control, or related effort, is required.

The expert texts for the three practices either state or imply that once the meditator has progressed a little way towards the goal-state/s, deliberate doing/control relating to the posture is not required, and there is therefore no associated effort. In Stillness Meditation it is said that, with practice, the minor discomfort of the posture is transcended in the first few minutes of each session (Meares, 1987/1991, p. 115). The body remains in the correct posture without deliberate doing/control, and any sense that the posture is effortful subsides (Section 2.3.2). Wallace (2010, p. 48) notes that, with practice, the Shamatha meditator “learn[s] to rest in a stable posture”, and this supports the idea that what happens in Shamatha with respect to posture is similar to what happens in Stillness Meditation.

Non-postural aspects

In this section, when we refer to doing/control and effort, we mean only those forms that are unrelated to posture. In the early and middle stages of Shamatha, there are various types of deliberate doing/control: The meditator must selectively attend to the meditation object (taking no interest in alternative objects), and they must introspect to detect excitation and laxity, and take measures to counteract them (Section 2.1; SH 1.10; Wallace, 2011a, pp. 180–182). These forms of deliberate doing/control require a degree of effort (Section 2.1.2; SH 1.10). At advanced stages, virtually no deliberate doing/control is required (Section 2.1.4; SH 1.10). The meditator has trained attention to remain on the object in a highly focused manner, and there is no or almost no excitation or laxity.

TM and Stillness Meditation appear to involve much less deliberate doing/control and associated effort than in Shamatha. For beginners or at the outset of a session there may be a small amount of monitoring with respect to aspects of the practices that are unrelated to posture, but monitoring is generally discouraged (see Section 2.4.5). Stillness Meditation does not involve a meditation object, and it therefore does not require any form of doing/control or effort entailed by the cultivation of selective attention.

The TM experts present TM as involving no deliberate control and no effort (Section 2.2.2). They base this principally on the understanding that the movement towards the goal-state is automatic. Travis goes so far as to say that TM involves no “directing of attention” (Travis & Parim, 2017, p. 90), and Roth (2018, p. 17) says similarly that there is “nothing guided”. A problem with the claim made by the TM experts is that it does not take into account the bringing of attention to the mantra at the beginning of a meditation session, or during the session when the meditator has ceased to transcend (Section 2.2.3). Bringing attention to the mantra clearly involves a degree of deliberate control. The TM experts implicitly recognize this, in that they do not claim that it occurs automatically. Nevertheless, they present the practice as a whole as automatic, overlooking this facet. As noted above, Lutz et al. (2015) indicate that deliberate control entails a degree of effort. Based on that view, effort is involved in bringing attention to the mantra. According to Williamson (2010, p. 87), Maharishi Mahesh Yogi acknowledged that bringing attention to the mantra involves a small amount of effort.

In Stillness Meditation, the meditator is advised to give up all doing/control from the beginning of a meditation session (Section 2.3.3). Deliberately bringing attention to a meditation object is regarded as a gross form of doing/control and is clearly not part of the practice. The question occurs, however, whether some more subtle element of doing or control might be involved. Since the practice is all about giving up the effort of doing anything, the key question is whether that itself involves some subtle doing or control. For example, a beginner meditator may notice in a session that they are applying effort to do something, such as quietening their thoughts. At a cognitive level, they then compare that to the instruction for the practice – to give up the effort of doing anything – and then implement that instruction by giving up the effort (Isbel & Summers, 2017). Arguably there is some guiding of mental experience here, and therefore an element of doing/control. However, from an experiential point of view, the meditator is simply relinquishing doing/control – the subtle element of doing/control is merely what is implicit in that relinquishment. Critically, the meditator does not have the attitude, “I must notice any effort I’m putting in, then recall the instructions, then give up that effort.” That would amount to having to do something in the practice. Experientially, the meditator simply gives up all doing.

The forms of deliberate doing/control in TM and Stillness Meditation discussed above relate to the earlier interim-states, where the meditator is beginning their movement towards the goal-state/s. In the later interim-states, where the meditator is well on the way to the goal-state/s, it is clearer that there is no or almost no deliberate doing/control.

There is one form of deliberate doing/control that tends not to be highlighted in the expert texts, but that may be required to some degree in the earlier interim-states in all three practices. This is the very basic form of deliberate doing/control involved in continuing in a meditation session rather than simply giving up. In Stillness Meditation, continuing in a session means maintaining the posture and essentially doing nothing. Once the meditator gains an initial familiarity with the practice, it is said to be easy and pleasant (Section 2.3.6), and it seems that little or no deliberate doing/control would be required to continue in a session. However, in the initial familiarization phase, a meditator may encounter anxiety, boredom or discomfort due to their not yet being used to the experience of non-doing (Section 2.3.4). The meditator does not need to do anything about these negative feelings. They simply ignore them, and in time they pass (McKinnon, 1991, 1983/2016). Nonetheless, the meditator does need to continue in the meditation session, rather than giving up. One would expect that the simple act of continuing in a session when experiencing negative feelings may involve at least some minimal deliberate doing/control and effort.

In Shamatha and TM, continuing in a session in the earlier interim-states involves maintaining the posture and engaging in the types of deliberate doing (e.g., returning attention to the meditation object) that we have already discussed. Shamatha and TM can also be taken to involve non-doing, since during a meditation session the meditator gives up many forms of doing that they would typically be engaged in in normal life. The non-doing in Shamatha and TM is less complete than in Stillness Meditation, but it is nonetheless a distinctive feature of the practices. Wallace says, for example, that “[S]hamatha entails doing almost nothing” (Wallace, 2006a, p. 49), and notes that “the vast majority of things that [one] could be doing … have been eliminated” (Wallace, 2011a, p. 181). On this basis it seems fair to conclude that, during the initial familiarization phase in Shamatha and TM, some meditators might also experience negative feelings associated with non-doing. As in Stillness Meditation, continuing a meditation session in the face of these negative feelings might require at least a minimal degree of deliberate doing/control and effort.

2.4.7 Ease, speed and frequency with which the goal-states are achieved

Based on the expert texts, the TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states are accessed much more easily, quickly, and frequently than the goal-state in Shamatha (see Sections 2.1.7, 2.2.6, 2.3.6). For meditators who have achieved an initial familiarity with the practices, up until advanced stages Shamatha requires more non-postural effort within meditation sessions than the other two methods (Section 2.4.6).Footnote 9 If the meditator is serious about achieving the goal-state/s, Shamatha also involves much more practice per day. Unlike in TM and Stillness Meditation, progressing to the Shamatha goal-state requires fulfilment of various highly demanding preconditions, and these are usually taken to include withdrawing from active life. Achieving the goal-state/s is said to be exceptionally rare in Shamatha, but usual in TM and Stillness Meditation provided meditators maintain their practice.

If the Shamatha preconditions are satisfied, it is estimated that around 5,000 to 10,000 hours practice will be required for meditators to transition through the interim-states and access the Shamatha goal-state. The TM experts imply that most meditators will achieve the TM goal-state within 60 hours practice.Footnote 10 It appears that meditators regularly access the Stillness Meditation goal-states within a similar time frame (see Sections 2.3.5 and 2.3.6).

TM experts often state or imply that the practice aims for a single goal-state, but their descriptions elsewhere suggest that there is variation in the experience that is aimed for (Woods et al., 2022a). Stillness Meditation also refers to there being a range of goal-states (Woods et al., 2022a). It appears that, with practice, TM and Stillness Meditation practitioners may progress within the goal-states, and that this involves moving from shallower goal-states to deeper ones. Taking Stillness Meditation as an example, in the shallower goal-states the meditator may still have very dull sense or body perceptions. As the meditator goes deeper, they lose those perceptions, and may eventually get to the deepest goal-state/s which they report as the simplest and most natural experience possible.

As explained above, the traditional accounts indicate that TM and Stillness Meditation practitioners access the goal-state experience much more easily and quickly than in Shamatha. What is not clear, however, is how long it takes for TM and Stillness Meditation practitioners to access specific goal-states. For example, McKinnon (1983/2016, p. 217) says that it may take some people 2 years (approximately 500 hours) to be having a “deep and fulfilling” experience of the goal-states in Stillness Meditation.Footnote 11 It is not clear, however, whether she has in mind merely the absence of perceptions (as opposed to very dull perceptions), the deepest goal-state/s, or something else. Her comment also leaves open the possibility that, prior to the 2 year mark, such meditators may be having shallower experiences of the goal-states, and that they may have their first experience of the goal-states soon after commencing their practice. Where TM is presented as having a single goal-state (as opposed to a range of goal-states), that can obscure variation in the experience, making it even more difficult to work out how long it takes to access specific states.

3 Discussion

3.1 Similarities and differences across the practices

In summarizing our findings from the comparison across the practices, we can first note that there are a number of dimensions for which our rating was the same or very similar across all three traditions. In each of the practices, there is a gradual settling or fading of thoughts, perceptions, and images, and increasing calm and relaxation. In the later interim-states there is also no or very low: introspection/monitoring; and deliberate doing/control, and associated effort, relating to the posture and otherwise.

For the remaining dimensions there are appreciable differences between two or all three practices. These dimensions can be split into those specifically relating to posture and those that are more general. On the postural dimensions (Fig. 4), Shamatha and Stillness Meditation are the same, and TM is different: In Shamatha and Stillness Meditation there is a little more discipline in the posture, and, as a consequence, in the earlier interim-states there is slightly more deliberate doing/control and associated effort relating to the posture.

Of the nine more general dimensions, one is binary (Yes/No) and the other eight are graded (e.g., None to Very high). On the binary dimension – whether or not there is a meditation object – Shamatha and TM are the same (Yes), and Stillness Meditation is different (No). Ratings for the eight graded dimensions are shown in the radar chart in Fig. 5.

Two main points stand out from the chart. The first is that the TM and Stillness Meditation profiles are similar, and the Shamatha profile is markedly different. This finding fits neatly with the understanding that Shamatha aims for exceptional/perfect attentional stability and vividness, whereas TM and Stillness Meditation do not (Section 2.4.2; Woods et al., 2022a). As Shamatha aims for exceptional stability and vividness, it involves: greater measures/steps to cultivate stability/vividness of attention on a meditation object; greater focusing/concentration; less tolerance of mind-wandering; more introspection/monitoring during the earlier interim-states; and more deliberate doing/control and associated effort (unrelated to posture) in that earlier phase. For the same reason, achieving the goal-state/s in Shamatha is much slower, more difficult, and less frequent.

The second point that stands out from the chart is that the Stillness Meditation profile/shape is narrower than that for TM. Principally, this appears to reflect that Stillness Meditation does not require the discipline of bringing or returning attention to a meditation object. That requirement in TM leads to higher ratings than Stillness Meditation for: measures/steps to cultivate stability and vividness of attention on an object; focusing/concentration; and deliberate doing/control and associated effort (unrelated to posture) in the earlier interim-states. It leads to a lower rating for tolerance of mind-wandering.

3.2 Application of meditation taxonomies to the practices