Abstract

Contentless experience involves an absence of mental content such as thought, perception, and mental imagery. In academic work it has been classically treated as including states like those aimed for in Shamatha, Transcendental, and Stillness Meditation. We have used evidence synthesis to select and review 135 expert texts from within the three traditions. In this paper we identify the features of contentless experience referred to in the expert texts and determine whether the experiences are the same or different across the practices with respect to each feature. We identify 65 features reported or implied in one or more practices, with most being reported or implied in all three. While there are broad similarities in the experiences across the traditions, we find that there are differences with respect to four features and possibly many others. The main difference identified is that Shamatha involves substantially greater attentional stability and vividness. Another key finding is that numerous forms of content are present in the experiences, including wakefulness, naturalness, calm, bliss/joy, and freedom. The findings indicate that meditation experiences described as contentless in the academic literature can in fact involve considerable variation, and that in many and perhaps most cases these experiences are not truly contentless. This challenges classical understandings in academic research that in these so-called contentless experiences all content is absent, and that the experiences are therefore an identical state of pure consciousness or consciousness itself. Our assessment is that it remains an open question whether the experiences aimed for in the three practices should be classed as pure consciousness. Implications of our analysis for neuroscientific and clinical studies and for basic understandings of the practices are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The vast majority of scientific research on meditation has focused on brain activity or other physiological markers during meditation practice, or on the effects of practising (e.g., changes in brain activity, cognitive performance, or self-report on clinical scales) following a session. Very little work has scientifically examined meditators’ subjective experience during meditation (Petitmengin et al., 2019; Przyrembel & Singer, 2018). This represents a major gap, as subjective experience is at the heart of every practice and is essential for making sense of the other types of data (Bitbol & Petitmengin, 2013; Przyrembel & Singer, 2018; Rigato et al., 2019; Schwitzgebel, 2008; Thompson, 2006/2008).

In various forms of meditation an objective is “contentless” experience, in which mental content such as thought, sense-perception, body-perception, and mental imagery is absent (Forman, 1990b, 1998; Shear, 2006d; Stace, 1960/1961).Footnote 1 The meditation traditions view the experience as important, on the understanding that it leads to wide-ranging positive outcomes, including improvements to mental and physical health (e.g., Meares, 1978/1986; Pearson, 2013; Wallace, 2006a). Academics have argued that, since the contents of consciousness are absent, the experience constitutes pure consciousness, or consciousness itself, and that it should therefore be prioritized as a research target in the field of consciousness studies (Forman, 1990b; Shear, 1990b; Stace, 1960/1961; but see, e.g., Dainton, 2000, 2002; Gellman, 2018; Lancaster, 2004; Studstill, 2005). Recent work at the intersection of cognitive science and philosophy has given it that focus (Costines et al., 2021; Gamma & Metzinger, 2021; Josipovic & Miskovic, 2020; Metzinger, 2020a, 2022; Millière, 2020; Millière et al., 2018). In that research, contentless experience is referred to using terms such as pure consciousness, consciousness as such, and minimal phenomenal experience.

This paper examines contentless experience in three meditation practices: Shamatha meditation as presented by Alan Wallace (Wallace, 2006a), Transcendental Meditation (“TM”) (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1967/1974, 1963/2001), and Stillness Meditation (McKinnon, 1983/2016; Meares, 1967/1968).

The Shamatha meditation described by Alan Wallace is a classic Tibetan Buddhist practice. It is one of many forms of shamatha meditation (Wallace, 2011a, b), and shamatha is the type of Buddhist practice most closely associated with contentless state/s (Gimello, 1978; Jones, 1993; Markovic & Thompson, 2016; Wallace, 2007b). In Shamatha practice, the meditator learns to pay attention to a meditation object, and then at a very advanced level relinquishes the object and moves into contentless experience (Wallace, 2006a).

Wallace describes Shamatha principally from the perspective of the Dzogchen tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The goal of Shamatha practice is the contentless experience. In the Dzogchen tradition, it is understood that by progressing all the way to the contentless state the Shamatha meditator develops attentional qualities that are considered a prerequisite for the effective practise of insight meditation (Sanskrit: vipashyana) (Wallace, 2006a, 2011a, b). Insight meditation is undertaken separately to Shamatha, and is seen as critical for achieving enlightenment, also known as pristine or nondual awareness (Josipovic, 2021; Wallace, 2005, 2011a, b, 2012).

Communities of dedicated Shamatha practitioners can be found throughout the world (e.g., www.centerforcontemplativeresearch.org). In the past decade, the practice has been the subject of a large-scale and long-running research program (see, e.g., Jacobs et al., 2011; Rosenberg et al., 2015; Zanesco et al., 2019).

TM is said to derive from the Vedic tradition of ancient India (Pearson, 2013; Roth, 2018; Shear, 2006c; cf. Williamson, 2010, p. 86). Maharishi Mahesh Yogi is understood to have isolated the technique from the broader set of traditional Vedic practices, and in the 1950s he began promoting it in India and overseas (Pearson, 2013; Rosenthal, 2011/2012; Roth, 2018; Shear, 2006c). In TM the meditator repeats a mantra silently in their mind, and this is said to lead to contentless experience, where awareness of the mantra falls away (Faber et al., 2017).

TM was initially presented as mainly for spiritual development, but it is now promoted more for its health benefits (Roth, 2018; Williamson, 2010). The technique was particularly popular in the 1970s (Farias & Wikholm, 2015; Holen, 1976/2016), and is still well recognized and widely practised. Most scientific research on contentless states in meditation has focused on TM (see, e.g., Vieten et al., 2018; for a detailed review of the TM research, see Pearson, 2013, pp. 399–430). The practice was the most researched form of meditation up to the early 1990s (Lutz et al., 2007; Shear, 1990b).

The third practice, Stillness Meditation, is a secular technique that was designed by the Australian psychiatrist Ainslie Meares (Meares, 1967/1968). Unlike Shamatha and TM, it is not well known and has received minimal research attention (e.g., Hosemans, 2017; Seymour, 1999; Woods et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Yerbury, 2021). Meditation research has focused on a narrow range of practices, but it is now recognized that there is a need to broaden this focus to methods that have been largely unexplored (Dahl et al., 2015; Goleman & Davidson, 2017; Matko et al., 2021).

Stillness Meditation was developed for the relief of anxiety and pain (Meares, 1967/1968). It is one of the first techniques specifically designed for use in a clinical setting (Gawler, 2011, 1984/2015; Gawler & Bedson, 2010/2011). Classical forms of meditation such as Shamatha were traditionally practised for spiritual or soteriological purposes and were not designed for the treatment of mental illness (Farias & Wikholm, 2015; Goleman & Davidson, 2017; Sedlmeier & Srinivas, 2016; Sedlmeier et al., 2018; West, 2016; cf. Hasenkamp, 2021; Waelde & Thompson, 2016). Use of Stillness Meditation in clinical practice predates Kabat-Zinn’s (1982, 1990) Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program by more than 10 years, illustrating the pioneering contribution of Ainslie Meares’ method in the field of meditation as therapy.Footnote 2

Stillness Meditation is significant from a technique perspective because it is extremely simple. Sitting in the correct posture, the meditator gives up the effort of doing anything (Woods et al., 2022a). There is no meditation object, and the meditator does not need to maintain any particular attention or awareness. Other practices have also been said to involve no doing, effort, structure, or technique, but close examination indicates that they almost always require at least minimal forms of these ingredients that are not present in Stillness Meditation (e.g., Adyashanti, 2006; Eifring, 2010, 2016; Goleman, 1988, pp. 98–100; for a detailed analysis of how Stillness Meditation differs to other techniques, see Woods et al., 2022a). Investigating the simplest practices that are said to access contentless states, like Stillness Meditation, may help to understand more complex approaches. The “methodological principle” is that “to understand something complex turn to its simple forms” (Forman, 1998, p. 185; Metzinger, 2018b, 2020a).

A high-level overview of Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation is provided in Fig. 1.

High-level overview of the three practices. Entries for each feature reflect the understanding within each meditation tradition. The primary purpose of reaching the contentless goal-states is as typically stated in modern texts for the general public (e.g., McKinnon, 1983/2016; Roth, 2018; Wallace, 2011b). A secondary purpose or benefit of reaching the Shamatha goal-state is reducing anxiety, improving mental and physical health/wellbeing, and achieving personal growth/development, and a further purpose of reaching the TM goal-state is that it is said to lead to higher states of consciousness in daily life. For detailed analysis supporting the assessment for the feature speed and ease of reaching the contentless goal-state/s, see Woods et al. (2022a)

In this paper we will use the term “goal-state” to refer to the subjective experience of a state aimed for in a practice.Footnote 3 We will use the term “interim-state” to mean an experience in the practice on the way to achieving the goal-state/s. In Woods et al. (2022a) we describe the main features of the techniques and interim-states in Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation. The present paper is focused on the goal-states in those practices.

One reason that contentless experience is of interest in cognitive science and philosophy is that it is so different from experiences in normal waking life. An enormous amount of scientific research has been conducted with respect to mental content such as thought, perception and mental imagery that typifies ordinary waking experience. On the other hand, there has been hardly any scientific research on meditative experience where that content is reported to be absent (Costines et al., 2021; Metzinger, 2020a; Vieten et al., 2018). It remains unclear precisely which content is absent in goal-states that are said to be contentless. Is it all content, or is there some content that is present? If there is content that is present, what could that be?

As indicated above, in the main strand of academic literature, goal-states like those in Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation have been described as contentless experience (Forman, 1990b, 1998; Shear, 2006d; Stace, 1960/1961). Contentless experience has been commonly presented as lacking all content, and on this basis it has been argued or assumed that all instances of contentless experience are identical (Almond, 1982; Bernhardt, 1990; Bucknell, 1989a, b; Forman, 1990a; Shear, 1990b). Based on these understandings, Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation each achieve an identical goal-state lacking all content despite the fact that they involve quite different techniques. Our analysis of expert texts from within the three traditions indicates that it is much quicker and easier to access the goal-states in TM and Stillness Meditation than the goal-state in Shamatha (Woods et al., 2022a, 2022b). This raises a further question, that overlaps with those above: Is it correct that the goal-states in the three practices are identical, or could it be that they differ in some way?

The present analysis addresses these questions. The aims are to: (a) identify the features of the goal-states referred to in expert texts from within the three traditions; and (b) determine whether the goal-states are the same or different across the practices with respect to each feature. To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to identify features of the goal-states in the three practices based on expert texts selected and reviewed using a scientific method. It is also the first detailed comparison of the goal-states across the three practices.

1 Method

1.1 Evidence synthesis

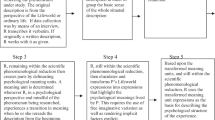

The current paper, together with Woods et al. (2020), constitutes an evidence synthesis compliant with the ENTREQ reporting guidelines for qualitative evidence syntheses (Tong et al., 2012). Online Resource 1 lists the section/s that address each of the 21 items on the ENTREQ checklist. The evidence synthesis process comprised four steps. The first three concerned the production of “extraction tables” containing textual material on the meditation techniques and experiences extracted from expert publications. These three steps are summarized in Fig. 2. The full method for these steps has been published as a separate document which has been peer reviewed and is available in an open access format (Woods et al., 2020). The fourth step in the evidence synthesis process involved comparing individual features of the goal-states across the three practices. That step is summarized in Fig. 3 and outlined in full detail in Online Resource 2 for the present paper.

Representation of steps 1 to 3 in the evidence synthesis process. The first step was to select for each practice samples of publications by expert/s with outstanding qualifications. Alan Wallace was selected as the expert for Shamatha; Craig Pearson, Norman Rosenthal, Bob Roth, Jonathan Shear, and Fred Travis as the experts for TM; and Ainslie Meares and Pauline McKinnon as the experts for Stillness Meditation. Samples of their publications were selected that revealed their understandings of the meditation techniques and experiences. For Pearson, Rosenthal, and Roth, the sample comprised recent major works that appear to present their understandings in a consolidated form. For the other five experts it comprised publications selected by applying eligibility criteria to their full output. For the eight experts combined, 135 publications were selected (panel a). The second step was to review the selected publications and extract (i.e., copy) information about the techniques and experiences. As an example, panel (b) is an excerpt from one of the Shamatha texts (Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 190). The highlighted statement, “All subtle and coarse thoughts vanish”, describes a feature of the Shamatha goal-state (“No thoughts”) and was therefore extracted. The third step was to place each extracted passage in an extraction table for the relevant practice and code it as indicating the relevant feature. To illustrate this, panel (c) is a simplified excerpt from the Shamatha extraction table. This excerpt relates to the “No thoughts” feature of the goal-state. In this example, the extracted statement “All subtle and coarse thoughts vanish” is coded “No thoughts” by placing it in this section of the Shamatha table. As can be seen, this section of the table also includes the other extracted passages that have been coded “No thoughts”

Representation of step 4 in the evidence synthesis process. In this step we assessed whether the goal-states are the same (i.e., identical) or different across the practices with respect to each feature. This involved systematically comparing the extracted passages for each feature of the goal-states across the three practices. In the example here, the arrows depict the cross-practice comparison of the extracted material for the feature “No thoughts”. The assessment “Unclear” (as opposed to “Same” or “Different”) was made if: (a) a feature was not described with sufficient precision to reach a finding of sameness or difference; or (b) the feature was reported/implied in one practice but not addressed in another. Stillness, naturalness, and relaxation are examples of features meeting condition (a). Each is reported/implied in all three traditions, but it was not possible to work out whether the precise nature and level/degree was the same across the practices

The extraction tables referred to above and in Fig. 2 are in total 194 pages and are supplementary material in Woods et al. (2020). In this paper we will refer to the tables using the abbreviation SH, TM or SM followed by the relevant section number.

1.2 Treatment of inconsistent descriptions

For some features of the goal-states, descriptions are inconsistent across experts in the relevant practice or within the texts of an individual expert. In Section 2 we focus on the majority, or more widespread, descriptions, but also note the minority views.

One minority understanding advanced by Shear is that the TM goal-state lacks all or virtually all forms of content other than being conscious and awake.Footnote 4 Other TM experts present the goal-state as involving numerous types of content in addition to being conscious and awake, and Shear also does this in other passages. As Shear’s minority understanding is relevant to almost all the features of the goal-states, we will not repeat it for each of those features in Section 2. Our assessments of whether the features are the same or different across the practices will be based on the majority descriptions. In the ground-states section (Section 2.14) we will explain a possible way to reconcile Shear’s minority understanding with the more widespread reports.

1.3 Sources outside the extraction tables

Our findings in Section 2 are derived from the expert passages in the extraction tables. In a few places we also refer to passages and publications outside the tables in order to provide important context and facilitate understanding. Most sources outside the tables are easily identifiable in that they are not authored by one of the eight experts selected for the evidence synthesis. The remaining sources outside the tables are passages by the experts that were not extracted in the tables. To distinguish those sources we have marked them with an asterisk.

2 Results

Table 1 lists the features of the goal-states that we identified from the expert texts, and summarizes our conclusions with respect to each feature. Table 2 lists the features and summarizes our conclusions in a more condensed form. Our detailed analysis supporting the conclusions is presented in Sections 2.1 to 2.18 of this paper. For clarity, in that analysis we have divided the goal-state features into 18 groups based on experiential or conceptual similarities or linkages (see further Online Resource 2).

2.1 Group 1 – conscious, awake, wakefulness

In each practice the meditator is said to be conscious and awake during the goal-state/s.Footnote 5 The experts indicate that there is a heightened level of wakefulness. For example, Wallace describes the Shamatha meditator as highly alert, and vividly or luminously awake (Wallace, 2011a, p. 109, 2012/2014, p. 199, 2009/2014, p. 92). Pearson (2013) refers to the mind being “awake to its depth” in TM (p. 45), and quotes a meditator saying “I have never been so clearly and entirely and fully awake” (p. 53). Meares (1967/1968, p. 59) describes the Stillness Meditation practitioner as “fully awake”.Footnote 6 It is not clear whether the heightened levels of wakefulness referred to in each practice are identical.

2.2 Group 2 – emptiness/nothingness

In all three practices, the basic understanding is that the goal-states involve no thoughts, images, memories, or feelings.Footnote 7 In each practice, it appears that sense and body perceptions fade gradually as the meditator moves towards the goal-state/s. The Shamatha and TM goal-states are said to involve a complete absence of perceptions. The Stillness Meditation goal-states are said to involve a complete absence of perceptions, or perceptions that are only very dull.

Very dull perceptions in Stillness Meditation means sense or body impressions that are so vague and distant as to not convey any meaning for the meditator. McKinnon (2011, p. 199) gives the example of hearing construction works undertaken outside the meditation room. To begin with, the noises are vividly perceived, but, as the meditation proceeds, they become vague and distant (McKinnon, 2011, pp. 69, 199, 1983/2016, pp. 221, 227; Meares, 1967/1968, p. 83, 1978/1986). By that point they are simply sounds without meaning: They are not recognized as stemming from the construction site, and they do not disturb the meditative experience. Eventually they may fade from consciousness altogether.

In all three practices, it appears that the meditator may be brought out of the goal-state/s by particularly salient stimuli. For example, if they set an alarm-clock to cue the end of a session, it seems that they will perceive the alarm (Meares, 1971a, p. 676, 1973a, p. 734; Roth, 2018, p. 65; Wallace, 2006a, p. 162).

Wallace (2018) speculates that in the Shamatha goal-state the meditator may be aware of the rhythm of their breathing. He distinguishes the rhythm of breathing from “tactile sensations” (p. 11), which he says the meditator will not be aware of. Wallace only makes the comment about rhythm of breathing in one publication. The comment is speculative, because he bases it on reports of what he regards as a similar state in lucid dreamless sleep, as opposed to meditation.Footnote 8 In the TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states the meditator is not aware of their breathing (Meares, 1978/1986, p. 15; Shear, 2014b, p. 211).

As referred to above, in all three practices the experts repeatedly state that there are no feelings in the goal-states. In other places, however, they identify features of the goal-states that could be construed as feelings. The most obvious examples are the experiences of bliss, goodness, calm, ease and peacefulness. In one publication Wallace indicates that loving-kindness is a feature of the Shamatha goal-state, but in a later text he states that it is not (Wallace, 2001a, pp. 212–213, 217, 2011a, pp. 137, 231–232).

When the experts say that there are no feelings, it appears that what they actually have in mind is particular feelings that are experienced in daily life. For example, they never refer to negative feelings as being part of the goal-states, which suggests that they understand those feelings to be absent. They may also have in mind certain neutral and positive feelings, such as any that are incompatible with other features of the goal-states. The experts implicitly distinguish between the relevant feelings experienced in daily life, and other types of feelings such as bliss, goodness, calm, ease, and peacefulness. The meditator moves beyond feelings of the first type, whereas feelings of the second type are generally presented as innate aspects of the meditator’s mind or being that are discovered as part of the practices.

In the TM goal-state/s the meditator is no longer aware of the mantra. Shamatha is somewhat similar, in that as the meditator enters the goal-state they release the meditation object. That means that they are no longer mindful of the object: They cease attending to it.Footnote 9 In Stillness Meditation there is no object at any point in the practice.

On the basis of the absence, or virtual absence, of various types of content, experts in all three practices note that there is little or no mental activity, and refer to the states as empty, or as involving nothing or an experience of nothingness. Wallace makes clear that the terms empty and emptiness in this context have a different meaning to their more common usage in Buddhist discourse (Wallace, 2006a, pp. 146, 148, 2011b, p. 175). Ordinarily emptiness refers to “[t]he absence of inherent existence of all phenomena” (Wallace, 2011b, p. 184*), whereas here it simply describes the absence of the various types of content.Footnote 10

Experts in the three practices use a number of terms to communicate the second type of emptiness. In TM, the goal-state is said to have no objects or qualities. TM and Shamatha refer to the goal-states as contentless and devoid of concepts. In Shamatha, non-conceptuality – meaning the absence of concepts – is presented as one of the fundamental features of the goal-state. Shamatha describes the emptiness as a vacuity or vacuum, and it refers to the absent content as dormant, in that it returns as the meditator emerges from the experience.

A closely related feature identified in Shamatha is the absence of grasping with respect to the absent content. TM and Stillness Meditation tend not to use the term grasping, but the emptiness of the goal-states implies that meditators in those practices have in some sense let go of the relevant content.

For the remainder of this paper we will use the term “everyday content” to describe the content that is absent, or virtually absent, from the goal-states. This is not a technical term, and we introduce it simply to provide a notation for that content. The word everyday signifies that the content is generally present in everyday waking life. The full term, everyday content, does not cover all of the content that is or may be present in everyday life. As a simple example, it does not include the sense of being conscious or awake, which remains present in the goal-states.

In each of the three traditions there is a clarification that the emptiness is not flat or barren, and that there is instead a depth or fullness to it. Referring to the empty “space of the mind” experienced in the Shamatha goal-state, Wallace (2011a, p. 215) comments, “This space is not an empty nothingness – it’s not flat empty”. He then refers to the paradox that “emptiness is full” (p. 215). Pearson (2013, p. 444) says that the TM goal-state/s may be initially experienced as “flat”, but that with practice the meditator may encounter “the internal, unmanifest reverberations, the inner dynamics of consciousness”. He describes what is experienced in the latter case as “infinitely silent and infinitely dynamic, both together” (p. 444). McKinnon (2011, pp. 101–102) quotes a Stillness Meditation practitioner who refers to a “nothingness”, but who then adds “yet it felt like everything”. Meares (1976/1984, p. 35) says that there is a depth to what is experienced, distinguishing it from oblivion (see Sections 2.15 and 2.18 for further discussion concerning depth).

2.3 Group 3 – nonduality and recognition in retrospect

Each of the practices identifies the absence of subject-object duality as a feature of the goal-states. In the Shamatha context, Wallace indicates that the dichotomy between the meditator and objects of experience is constructed by concepts (Wallace, 2010, p. 50), such as “‘I’ and ‘not I’” (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 94). Since there are no concepts in the goal-state, there is no subject/object dichotomy. Wallace (2010) says that, “[T]here is no longer a sense of the meditator” (p. 50), and that what is left is “just the experience” (p. 49).

The TM texts refer to the subject/object or “I … it” (Shear, 1990b, p. 102) structure collapsing due to the absence of objects such as thoughts, perceptions, and the mantra. Pearson (2013, p. 47) says that the subject, consciousness, “becomes its own object of experience”, so that “the subject is the object”. Shear (1990b, p. 102) says that “the subject finds himself … alone … simply self conscious, without any object of awareness”.

In Stillness Meditation, the absence of subject/object duality is described with reference to the relaxation that develops in the practice (Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 19–20, 24–25). In the early stages of a meditation session, the individual has a sense of themselves, as subject, feeling the relaxation of the body, one of the objects of experience. As the session progresses, the relaxation deepens and becomes more prominent, extending beyond the body and permeating the meditator’s whole being. The meditator – or equivalently, the subject/being – is then said to participate in the experience, rather than standing apart from it: “The separate entities cease to be separate” (Meares, 1978/1986, p. 20).

While the absence of subject-object duality is described in different terms in the three traditions, it could still be identical across the practices. The Shamatha and TM descriptions focus on the absence of everyday content (including concepts), and the absence of that content is also a feature in Stillness Meditation. The Stillness Meditation description emphasizes the absorptive nature of the relaxation. Shamatha and TM also involve deep relaxation, although it is not necessarily absorptive in the same way as in Stillness Meditation. It could be that the nonduality in the three practices comes about in different ways, but that the experience of it in the goal-states is still the same.

A separate but closely related feature concerns the point at which the goal-state experience is recognized. The TM and Stillness Meditation experts expressly state that the meditator only becomes aware that they have experienced the goal-states once they emerge from them. Wallace does not explicitly make this point for Shamatha, but it is implied by the fact that the Shamatha goal-state involves no introspection, thought or conceptualization. TM and Stillness Meditation experts elaborate on the point by noting that if the meditator is examining their state of mind, or has a thought such as “My mind is still”, they are not experiencing the goal-state at that moment. Experts in all three traditions indicate that once the meditator emerges from the goal-state/s they are able to remember the experience.

2.4 Group 4 – stillness, silence, simplicity, naturalness

In each practice, the goal-state/s are said to involve an experience of stillness, silence, simplicity, and naturalness. The experts often allow those terms to speak for themselves, rather than elaborating as to their meaning. The passages that do elaborate with respect to the term stillness suggest that it usually reflects the absence of disturbances such as thoughts, perceptions, and negative feelings. The terms silence and quietness reflect at least the absence of thoughts and sounds. The experts also leave scope for them to be interpreted as extending to the absence of other disturbances such as negative feelings. The feature silence/quietness is explored in more detail in Woods et al. (2020).

2.5 Group 5 – calm, relaxation, rest

Calm, ease and peacefulness are described as features of the goal-states, again reflecting that the mind is no longer disturbed by thoughts, perceptions, negative feelings, and so on. The meditator is relaxed, and experiences mental rest. Any earlier sense of discomfort from the posture or any other source is lost. In TM and Stillness Meditation there are explicit statements or reports that there is no sense of anxiety (McKinnon, 2011, p. 84; Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 26, 151, 160; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 39; Roth, 2018, pp. 66–67). Wallace does not expressly make that point for Shamatha, but it seems implied by his descriptions of the calm, ease and peacefulness.

2.6 Group 6 – bliss/goodness

Wallace presents bliss as a feature of the Shamatha goal-state, and Pearson, Rosenthal and Roth treat it as part of the TM goal-state. Shear sometimes treats it as part of the TM goal-state (Shear, 1990b, p. 172, 2006b, p. xix, c, p. 44, 2011a, pp. 142–143), and other times he expressly states that it is not (Shear, 1990a, p. 396, 2002, p. 378, 2014a, p. 60). Shear claims that bliss is experienced in interim-states that immediately precede the TM goal-state (TM 1.8.2). In one place he says that authors sometimes conflate these interim-states, where there is bliss, with the goal-state, where there is none (Shear, 2002, p. 378). He appears to be suggesting that this is the reason those authors incorrectly treat bliss as part of the goal-state. Travis, the final TM expert, tends not to refer to bliss.

In Shamatha and TM, bliss is also referred to as joy, happiness, and a sense of wellbeing. Wallace indicates that the bliss in Shamatha derives from the calm and peacefulness of the goal-state: It is experienced when the mind is no longer being “pummeled to death with afflictions, craving, hostility, and aversion” (Wallace, 2010, p. 32). He refers to it as the “joy of serenity” (Wallace, 2005, p. 109) and as a “bliss or joy that is quiet and serene” (Wallace, 2011b, p. 145). Rosenthal similarly identifies the close connection between the bliss, calm and peacefulness in the TM goal-state. He observes that peacefulness is one facet of bliss, alongside joy and happiness (Rosenthal, 2016/2017, p. 36), and he refers to bliss as “calm pleasure” (Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 38).

The bliss in the Shamatha goal-state is consistently presented as “subtle” (Wallace, 1998/2005, p. 207, 2005, p. 109) and “subdued” (Wallace, 2011b, p. 145), and therefore vastly different to the intense bliss that is said to be experienced in the interim-state immediately prior to achieving the goal-state (SH 1.11.10; Wallace, 2006a, p. 156, 2010, p. 66, 2011a, p. 97). For TM, on the other hand, there seems to be variation in how the magnitude or intensity of the bliss is described. For example, Pearson (2013, p. 45) states that “[n]o experience fills the mind with greater happiness”, and Shear (1990b, p. 42) indicates that bliss is experiencing “the ultimate object of all desires”. Rosenthal (2016/2017, p. 39), in contrast, comments: “My own transcendent experiences and those of most of my patients are pleasant but unsensational”. That suggests a more subdued experience of bliss than those referred to by Pearson and Shear.

The Stillness Meditation experts do not present “bliss” as a feature of the goal-states. However, they say that meditators experience the goal-states as good or wonderful, and as involving a sense of joy or wellbeing. In Shamatha and TM the term bliss is used synonymously with words like joy and wellbeing, and those terms can capture the sense that an experience is good or wonderful. As such, even though the word bliss is not relied on in Stillness Meditation, the feelings being described in that practice could be similar to those in Shamatha and TM.

As for Shamatha and TM, one source of the positive feelings in Stillness Meditation is said to be the calmness of the experience (Meares, 1976/1980, p. 134, 1978/1986, p. 155). The Stillness Meditation experts also identify other sources, including the sense that the experience is effortless (Meares, 1969c, p. 84).

McKinnon (2002/2008, p. 45) says that terms like “bliss … rapture [and] exaltation” are not typically used to describe the Stillness Meditation goal-states, which suggests that the positive feelings in the goal-states are subdued in comparison to more intense forms. Meares states that “ecstasy” can be part of the Stillness Meditation experience, but he indicates that it is not a feature of the deepest goal-state (Meares, 1976/1984, p. 12, 1978/1986, p. 145). It is unclear whether he means that ecstasy can be part of the shallower goal-states, or whether he is referring only to the interim-states.

2.7 Group 7 – luminosity

Wallace refers to luminosity as a fundamental quality of consciousness. It is the quality that illuminates whatever appears to the mind and without which nothing would appear (Wallace, 2011b, p. 95, 2009/2014, p. 90). According to Wallace (2018, p. 44), the quality is normally obscured by the everyday content. In the Shamatha goal-state that content is no longer present. Luminosity is said to illuminate the resulting vacuity or emptiness (Wallace, 2011b, pp. 176–177, 2009/2014, p. 90), and the luminosity is said to “[become] manifest” due to its being no longer obscured (Wallace, 2018, p. 44).

Wallace also treats luminosity as synonymous with vividness, which refers to the clarity of attention (Wallace, 2011a, p. 243, b, pp. 120, 186, 2012, p. 17). It therefore appears that luminosity can describe both the vividness or clarity of attention with respect to appearances, and the quality that allows the meditator to be conscious of those appearances at all. Wallace seems to address the first aspect – vividness or clarity – when he comments that in the Shamatha goal-state there is an “exceptional degree of luminosity” (Wallace, 2011a, p. 232). We will discuss the vividness, or clarity, in Shamatha, TM and Stillness Meditation in Section 2.16.

Terms like clearness, purity, transparency, radiance, and limpidity are often relied on by Wallace in his comments about luminosity. These terms appear to refer to features of the Shamatha goal-state that are the same as those discussed elsewhere in this Section 2, or that are very similar. The words clear, pure and transparent are used, at least in places, to indicate the absence of everyday content (Wallace, 2005, p. 165, 2006a, p. 144, 2011a, p. 232, 2018, p. 44). Clearness, therefore, does not necessarily equate to the term clarity, which tends to refer to vividness (e.g., Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 207). The terms radiance and radiant clarity are generally used as synonyms for luminosity, vividness and clarity (Wallace, 2011b, pp. 98, 120; Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 192). Limpidity can indicate both the absence of everyday content and luminosity (Wallace, 2001/2003, p. 90).

The term luminosity is not used in the TM or Stillness Meditation accounts. Those accounts also do not clearly identify and label a particular quality of consciousness that illuminates appearances to the mind, as luminosity is said to do in Shamatha. It follows that there is no clear discussion in the accounts about whether that quality is noticed in the goal-states. Nevertheless, in the TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states the meditator is said to have a conscious experience of emptiness. Adopting the Shamatha understanding, that would mean that the emptiness in those goal-states is somehow illuminated, implying that there is a form of luminosity. It is possible that this quality is both present and noticed in the TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states, but that it is not labelled and commented upon in the texts for those practices as it is in Shamatha.

TM and Stillness Meditation use the words clear, clarity, and pure or purity (TM 2.7.10–2.7.11; SM 2.3.3), but those terms do not appear to add anything to the features of the goal-states discussed above and below. For example, the term pure consciousness is used heavily in TM. The word pure in that context refers to the absence of everyday content in the TM goal-state, and to the understanding that the experience is of consciousness itself. As a further example, the term clarity in Stillness Meditation suggests that the goal-states involve a degree of vividness and are not drowsy. We discuss vividness in Section 2.16, and the absence of drowsiness is incorporated in the understanding that the meditator has a heightened level of wakefulness.

2.8 Group 8 – knowledge/knowing

Wallace treats cognizance or knowing as another fundamental quality of consciousness alongside luminosity. Luminosity illuminates appearances such as thoughts and images, whereas cognizance is the quality of knowing that they are there and recognizing them for what they are (Wallace, 2005, p. 37, 2011a, p. 229). The Shamatha goal-state is said to be empty, but the quality of knowing remains. Wallace describes it as a knowing that the mind is empty (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 90), “knowledge before knowledge of anything else” (Wallace, 2005, p. 191), and “the very nature of [knowing]” (Wallace, 1999b, p. 444). He also refers to it as a “nonconceptual knowing” (Wallace, 2011a, p. 297) and a “deep knowledge that is implicit rather than explicit” (Wallace, 2011a, p. 187).

TM and Stillness Meditation also refer to some sort of knowing or knowledge in the goal-states. Pearson (2013, p. 47) notes that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi referred to the TM goal-state as involving “pure knowledge” or a “state of knowingness”. Pearson contrasts that with the “knowledge of specific things” that is a feature of consciousness in normal life (p. 47). Rosenthal (2011/2012, p. 39) quotes a meditator who says that in the TM goal-state they experience “a knowing that is very beautiful”. The Stillness Meditation accounts also refer to a form of knowing or knowledge that is different to the types experienced in normal life. Meares (1987a, p. 9) describes it as “the spirit of what we need to know [r]ather than knowledge itself”. Like in Shamatha, he emphasizes that this knowledge is beyond thoughts and words (Meares, 1979b, p. 81, 1980e, p. 3, 1976/1984, pp. 22–23).

2.9 Group 9 – relinquishment of control, control, effortlessness

Relinquishment of control is presented as a fundamental element of each practice. A basic principle is that the meditator relinquishes control in the interim-states in order to move into the goal-state/s. The Shamatha and TM accounts contain little reference to the meditator having a sense of the relinquishment of control in the goal-state/s. However, it is clear from those accounts that the meditator does not reassert control in the goal-states, which suggests that they would describe those states as involving the relinquishment of control. The Stillness Meditation accounts establish more clearly that the meditator has a sense of the relinquishment of control in the goal-states.

The main type of control that the three practices refer to as having been relinquished is deliberate control. The experts tend not to use that specific term, but it provides a useful shorthand for what they are describing. Control can be thought of as the guiding of mental or physical experience or action (Christoff et al., 2016; Markovic & Thompson, 2016). In the goal-states, there is no deliberate doing, or guiding. For example, upon reaching the Shamatha goal-state, the meditator has eliminated excitation and laxity, and therefore no longer needs to monitor to detect them.Footnote 11 In the TM goal-state the meditator has transcended the mantra, so does not need to return their attention to it. The Stillness Meditation practitioner has from the beginning relinquished all deliberate doing and control, other than that required to maintain the posture. Once their body comes to automatically remain in the correct posture, deliberate doing and control are not required for that either.

Meares provides detailed descriptions of the relinquishment of an additional form of control in Stillness Meditation (Meares, 1967/1968, pp. 87–88, 1978/1986, pp. 27–29, 147). It is clear from these descriptions that what is being relinquished is a form of automatic control, although Meares does not use that particular term. He notes, for example, that the control does not come from the “voluntary level of [the] mind” (Meares, 1978/1986, p. 29).

Experientially, the meditator finds that with each session they can progress a little further, either towards the goal-states, or into deeper goal-states. For example, Meares (1978/1986, p. 147) describes the “letting go of ourself” that is initially experienced in the goal-states, and the “deeper process of simply ‘letting ourself’” that is subsequently encountered. McKinnon (1983/2016, p. 227) refers to the relinquishment of automatic control in the goal-states by saying, “You let go into [the stillness] more and more and more completely”. The meditator has the sense that previously there was something holding them back: a form of automatic control exerted over themselves. With practice, they are able to relinquish that control in whole or in part, allowing them to progress.

Certain of Wallace’s descriptions in Shamatha could arguably also be interpreted as indicating a relinquishment of this form of automatic control (e.g., Wallace, 2006a, p. 100, read together with Wallace, 2011a, pp. 179–184). However, neither Wallace’s account nor the TM passages refer to this relinquishment clearly and directly, as done in Stillness Meditation. Given that relinquishment of control is regarded as fundamental in Shamatha and TM, it seems plausible that the relinquishment of automatic control described in Stillness Meditation is also part of those practices.

In Stillness Meditation, relinquishing the automatic control in the goal-states allows the meditator to go deeper, until they reach the deepest goal-state. In Shamatha and TM, whether the meditator can go deeper in the goal-state/s in a similar way depends on whether the goal-state/s are understood as a single state or a series of deepening states. If there is no deepening in the goal-states, it could still be that the relinquishment of automatic control and the associated deepening of experience occur in the interim-states.

The Stillness Meditation experts indicate that the meditator may also have some sense of calm control in the goal-states. The meditator maintains the posture throughout the practice, which requires a form of automatic control different to that referred to in the paragraphs above. Meares (1978/1986, p. 40) explains that maintaining the posture leads to the “simultaneous experience of complete relaxation and effortless control”, and McKinnon (2011, pp. 67, 81) refers to this as “calm control”.

The Shamatha and TM accounts do not refer to this sense of calm control in the goal-states. However, both those practices appear to require forms of automatic control during those states: In each practice the posture is maintained, and in Shamatha there is single-pointed attention. It therefore seems plausible that meditators in those practices also have some sense of calm control, even though the experts do not mention it.

In Shamatha, the goal-states are referred to as effortless and as involving no effort, and in TM and Stillness Meditation the entire practices are described that way (see further Woods et al., 2022a). In each practice, it is clear from the expert texts that, since there is no deliberate doing/control in the goal-states, there is no effort associated with such doing/control, and the goal-states are therefore effortless in that sense. The Stillness Meditation texts arguably indicate that there are subtle forms of effort associated with the form of automatic control that is relinquished in the goal-states. On that understanding, in the deepest goal-state (where much or all of that automatic control has been relinquished) there is an even greater effortlessness than in the shallower goal-states. McKinnon (2002/2008, p. 45) says that the deepest goal-state is “beyond effort … of any kind”. It is plausible that all three practices involve the release of subtle forms of effort linked to the relevant form of automatic control, but the textual evidence on this point is inconclusive.

2.10 Group 10 – ego dissolution, freedom, spaciousness

Loss of ego is referred to as a feature of the goal-states in all three practices. Wallace states that in the Shamatha goal-state there is no ego, sense of self, sense of “I” or “mine”, or personal history or identity. The TM passages are similar, referring to the TM goal-state/s as beyond ego, sense of self, sense of “I” or “me”, personality, and individuality. McKinnon says that in the Stillness Meditation goal-states there is no ego.

Meares and McKinnon indicate that meditators can experience a loss of self/world boundaries in the Stillness Meditation goal-states. Meares (1978/1986, pp. 152–153) explains that meditators may report a sense of merging with the world around them, and McKinnon (2011, p. 118) describes the sense of “communion with all things”. In TM there are also explicit descriptions of the loss of self/world boundaries (Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 37; Shear, 1990b, p. 230), and the word unbounded is frequently used without elaboration.

Wallace does not expressly refer to a loss of self/world boundaries in the Shamatha goal-state. He does, however, describe the goal-state as involving freedom, spaciousness, and unity, and it is possible that the loss of boundaries is incorporated in one or more of those features. Wallace does not describe the three features in much detail.

The experience of inner freedom is also reported in TM and Stillness Meditation. The term freedom is usually used in Stillness Meditation to describe the meditator’s sense that there is nothing holding them back within the experience. That appears to reflect that the meditator has relinquished all deliberate control and, at a certain point, will have relinquished the relevant form of automatic control. In TM the term freedom similarly relates to the absence of limitations or restraints (Pearson, 2013, p. 396; Travis et al., 2005, p. 128). These include self/world boundaries (Shear, 1990b, p. 230), and presumably also relevant forms of control.

Describing the Stillness Meditation goal-states, McKinnon (2011) refers to “spaciousness and comforting enclosure” (p. 81), and an experience that is “closed yet spacious” (p. 101). She does not elaborate on what she means by the terms spacious, enclosure or closed. The TM experts do not use the term spacious to describe the TM goal-state, and the terms enclosure and closed are not used in TM or Shamatha.

Wallace describes the ego as the sense of “I am”, and repeatedly indicates that this will be strengthened by any deliberate doing or control on the part of the meditator (Wallace, 2006a, p. 49, 2011a, pp. 179–184). As discussed above, the experts in all three practices make clear that there is no deliberate doing or control in the goal-states, which implies the complete loss of any sense of self derived from such doing or control.

The Stillness Meditation texts may be read as indicating that there is a sense of self that derives from the form of automatic control that is said to be relinquished in the goal-states in that practice. That sense of self could be understood as including the self/world boundaries referred to above, but there may also be other facets (see Meares, 1978/1986, pp. 145–160). As noted above, it is possible that Shamatha and TM also involve a relinquishment of the relevant form of automatic control. To the extent that there is a sense of self that derives from that control, the relinquishment of the control in a practice will lead to loss of that sense of self.

While the TM and Stillness Meditation experts refer to there being no ego in the goal-states, and the TM experts at times indicate that there is no sense of self, in both practices meditators may describe the goal-states (or at least the deepest goal-state) as an experience of their true self (see Section 2.14 below). This suggests that certain dimensions of self are lost in the goal-states but that a deeper sense of self may be revealed. The Shamatha texts do not refer to the goal-state in that practice as involving an experience of the true self.

2.11 Group 11 – integration and security

In each practice the experts indicate that the goal-states involve a sense of wholeness, unity, and integration or coherence. TM and Stillness Meditation emphasize this aspect more than Shamatha, but in Shamatha there are still clear references to it.

The four qualities are often referred to briefly, without elaboration. The elaboration that is provided suggests that the qualities may have multiple facets. For example, Rosenthal (2016/2017, p. 234) and Meares (1978/1986, pp. 19–20) refer to the sense of unity from transcending the duality between subject and object; Meares (1978/1986, p. 149) talks about the unity of no longer experiencing body and mind as separate; and Wallace (2011a, p. 208) notes the unity between awareness and the emptiness, brought about by the absence of everyday content. McKinnon (2011, pp. 85, 118, 203, 1983/2016, p. 195) refers to the meditator’s sense of integration, coherence and unity both within themselves, and with the world around them. The latter aspect reflects the loss of self/world boundaries described in Section 2.10.

Certain of the features discussed in the sections above, such as calm, peacefulness, bliss, joy, and no feeling of anxiety, suggest some sense of inner security, safety, strength and contentment. Those latter four qualities are also clearly and repeatedly referred to in TM and Stillness Meditation. For example, in the TM context one meditator refers to feelings of strength, invincibility, and being taken care of (Pearson, 2013, p. 185), and another comments that “Everything seems right” (Travis et al., 2005, p. 128). McKinnon (2011) similarly refers to the Stillness Meditation experience as involving “a very safe and content knowledge that all is well” (p. 101), and she quotes a meditator saying that, “Everything I needed – safety, security, strength, peace – was within that stillness” (p. 102).

In Shamatha, Wallace tends not to emphasize security, safety, strength and contentment beyond what is suggested by the features calm, peacefulness, bliss, and so on. He does, however, quote nineteenth-century Buddhist contemplative Lerab Lingpa as saying that the experience can provide “a non-conceptual sense that nothing can harm the mind” (Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 218).

2.12 Group 12 – timelessness and spacelessness

In each practice the goal-states are said to be timeless. Wallace (2006a, p. 162) says that the Shamatha meditator may have “little or no experience of the passage of time”. Wallace explains that sense of time is dependent on conceptualization, and refers to the absence of conceptualization in the Shamatha goal-state. He notes, however, that before entering the goal-state the meditator can cue themselves to emerge after a specified period or when prompted by an external stimulus such as an alarm clock.

The Shamatha practices conclude with the Shamatha goal-state, but if the meditator wishes they may proceed to deeper states via separate practices (see, e.g., Lati Rinbochay & Denma Lochö Rinbochay, 1983/1997; Wallace, 1998/2005, p. 92, 2010, pp. 84–85*).Footnote 12 Wallace (2011a, p. 292) indicates that there are gradations of timelessness, and that timelessness becomes more complete as a meditator moves from the goal-state through the series of deeper states. He refers to time having vanished in each of these states, but indicates that it is only at the end of the series that “time is completely stopped” (p. 292).

The TM goal-state is referred to as being “beyond time” (Pearson, 2013, p. 265; Rosenthal, 2011/2012, p. 18) and “devoid of [temporal] content” (Shear, 1990a, p. 392). However, Roth (2018, p. 58) notes that many TM meditators say that “time passes quickly”. That comment suggests that the meditators emerge from the goal-state and discover that more clock-time has passed than the way it feels when reflecting on the experience. This raises the possibility that, although the goal-state is in some sense timeless, there is still some temporal content.

Meares and McKinnon say relatively little about time and the Stillness Meditation goal-states. Meares (1976/1980, p. 190) simply observes that sense of time is distorted, and McKinnon’s main comment is that the states are timeless.

In summary, it appears that the goal-states in all three practices are in some sense timeless, but it is not clear exactly what is meant by that term, and in particular whether all temporal content is absent.Footnote 13

TM experts say that the goal-state involves no sense of space. Shear (1990a, p. 392), for example, says that “by all accounts … spatiality … [is] not present”, and Rosenthal (2011/2012, p. 18) refers to the feeling of going beyond space. As discussed above, Wallace and McKinnon describe the goal-states in Shamatha and Stillness Meditation as spacious, but it is not clear exactly what they mean by that term. Wallace and the Stillness Meditation experts do not clearly refer to all sense of space being absent.

2.13 Group 13 – spiritual aspect and energy

In each practice the experts indicate that some meditators may report there having been some spiritual aspect of the goal-states. For example, Wallace discusses the possibility of meditators referring to the Shamatha goal-state as “[belonging] to God” (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 59), or “holy” (Wallace, 2011b, p. 159). Rosenthal (2011/2012, p. 38) quotes a meditator referring to the TM goal-state as “a touch of heaven”, and Pearson (2013, p. 264) notes that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi regarded it as an aspect of God. Meares (1984, p. 147) says that meditators have reported that in the Stillness Meditation goal-states they have gained glimpses of a “[spiritual] dimension of [their] being”.

The Shamatha and Stillness Meditation accounts indicate that two meditators may have the same experience but interpret it differently (Meares, 1984, p. 47; Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 59). One may interpret some facet of the experience as spiritual, while another may interpret it simply as one of the features discussed above and below. It is not clear from the accounts in the three practices whether it is possible for the spiritual element to be something beyond those features.

Rosenthal (2016/2017, pp. 217, 221–222) quotes two meditators who refer to a sense of energy flowing through them in their TM practice. However, those people also refer to having sense or body perceptions, which suggests that they may be describing interim rather than goal states. Roth, in the TM context, and Wallace, in Shamatha, also refer to energy as an aspect of the states aimed for in those practices. It is not clear, though, from those references whether energy is a feature of the goal-states that is distinct from those discussed above and below. For example, Wallace says that the Shamatha state “possesses structure and energy, characterized by such attributes as bliss … luminosity … and [subject-object nonduality]” (Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 192). That statement does not establish that the meditator has a sense of energy over and above those other features, but it does not rule it out either.

In Stillness Meditation energy is not referred to as being part of the states aimed for in the practice. McKinnon (2011, p. 108*) says that in those states “all energy is resting”.

2.14 Group 14 – ground-state

Wallace describes the Shamatha goal-state as a “ground state” of consciousness or the mind. He refers to it as the “relative” ground-state, and distinguishes that from pristine awareness, the “absolute” or “ultimate” ground-state accessible via more advanced practices (SH 2.6; Wallace, 2006a, p. 137, 2011b, p. 27). Wallace calls the Shamatha goal-state the natural state, or the essential nature, of the mind (SH 2.14.30; Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 151), and notes that a meditator may interpret it as a deep dimension of their being (Wallace, 2009/2014, p. 59). He explains that, in the Shamatha context, the term essential nature of the mind refers to the mind’s relative or conventional nature (Wallace, 2011b, p. 177). The term can also be used to describe pristine awareness, but there it means the mind’s ultimate or fundamental nature (Wallace, 2006a, p. 137).

Pearson, Shear and Travis indicate that, like in Shamatha, the TM goal-state is a ground-state of consciousness or the mind. In Stillness Meditation the experts do not use the term ground-state. However, Meares refers to the “full” (Meares, 1978/1986, p. 145) or “final” (Meares, 1987/1991, p. 127) experience in the practice, and McKinnon (2002/2008, p. 45) speaks about the “ultimate sensation”. Viewed in context, these passages appear to be referring to the deepest goal-state among a range of Stillness Meditation goal-states (see further Section 2.18). This deepest goal-state could be treated as a ground-state.

Similarly to Shamatha, in the TM and Stillness Meditation ground-states the meditator is said to experience the essential nature of their mind or being. In all three practices, the features of the goal-states such as stillness, calm, and naturalness are presented as aspects of that essential nature. In other words, those features are depicted as innate: Meditators have the sense of discovering them within themselves, and of recognizing that they have been there all along.

In places, the TM and Stillness Meditation experts indicate that the respective ground-states are the simplest and most natural experience/s possible (Meares, 1984, p. 52, 1978/1986, p. 27; Pearson, 2013, pp. 44, 49). Wallace states that in the Shamatha ground-state the meditator experiences “utter simplicity” (Wallace, 2005, p. 189), and his labelling of it as the natural state of the mind suggests a very high degree of naturalness. Unlike in Shamatha, the TM and Stillness Meditation experts do not refer to there being any deeper ground-state accessible via other meditation practices.

Wallace describes the Shamatha goal-state as consciousness or awareness itself, and Pearson, Shear and Travis say the same of the TM goal-state. Pearson, Shear and Travis use the term pure consciousness in this context, whereas Wallace does not. Wallace (2006a, p. 123) emphasizes that the Shamatha goal-state is “the nature of consciousness in its relative ground state”. From the Shamatha perspective, pristine awareness is the ultimate nature of consciousness (SH 2.6). In contrast to Shamatha and TM, the Stillness Meditation ground-state is not described as consciousness or awareness itself.

In TM and Stillness Meditation the ground-states are referred to as simple or pure being. Rosenthal (2016/2017, pp. 238–239) quotes a TM meditator saying, “It’s pure being. It’s is-ness, pure am-ness. It is the essential nature of existence”. Meares (1978/1986, p. 27) explains similarly that the Stillness Meditation ground-state is “the unadorned, primordial experience of existence”: “the act of just being … with nothing added at all”. In TM and Stillness Meditation, the ground-states are also described as an experience of the true, underlying, innermost, or deepest self. When discussing simple/pure being or the self, the TM experts sometimes use title case, referring to Being and Self (capitalized). In places they do this to make clear that the experiences of being and self are different to those in everyday life (Arenander & Travis, 2004, p. 114; Pearson, 2013, p. 46; Shear, 2006b, p. xvii). They may also do it, at least in places, to hint at metaphysical aspects of the experience (Shear, 2006b, p. xix; Shear & Jevning, 1999a, p. 193; TM 2.4). Wallace does not describe the Shamatha ground-state as simple or pure being, or as the self.

In a small number of passages Meares indicates that in the Stillness Meditation ground-state the meditator is beyond calm, stillness and/or the sense that the experience is good.Footnote 14 The passage that makes this point most clearly relates to the experience of calm. Meares (1976/1984, p. 36) says: “When being comes we are beyond calm. How could you be calm [i]f you were simply being?”. The passages could be read as indicating that the ground-state is different from other Stillness Meditation goal-states, in that in the ground-state there is no experience of calm, stillness or goodness. However, Meares’ broader comments concerning the ground-state give the impression that, having experienced it, the meditator would still recognize that their mind had been calm and still and regard the experience as positive. Furthermore, McKinnon (2002/2008, p. 45) refers to the ground-state as involving a “calm sense of [being]”. These broader passages raise the possibility that the ground-state in some sense involves calm, stillness and goodness, but in another sense is beyond them. As the discussion in this paragraph illustrates, it is not clear from the Stillness Meditation accounts exactly how the ground-state is beyond these features.

In the Shamatha accounts there is nothing to suggest that the ground-state is somehow beyond calm, stillness or bliss. There is also little in the TM accounts, other than Shear’s minority understanding that the TM goal-state involves no or virtually no content other than being conscious and awake. It seems possible that, similar to what Meares describes, there are a series of TM goal-states, and that the deepest state is somehow beyond content such as calm, stillness and bliss. That might provide a way to reconcile Shear’s minority understanding with the more widely held view of the TM experts that those types of content are present in the TM goal-state. This possibility is, however, not something that is explicitly canvassed in the TM accounts.

2.15 Group 15 – deep and profound

Wallace describes the Shamatha goal-state as deep, while noting that pristine awareness is understood to be the deepest level of the mind or consciousness (SH 2.14.41, 2.6). Roth, Shear and Travis treat the TM goal-state as the deepest level of consciousness, being or self. Meares (1976/1984, p. 52, 1978/1986, p. 49) describes even the most basic Stillness Meditation goal-states as deep, in that they involve almost no everyday content. He and McKinnon present the goal-states as deepening as the meditator moves towards the ground-state.

The experts in the three practices refer to particular features of the goal-states, such as stillness, silence or calm, as being deep. At other times they state simply that the goal-states are deep, which suggests depth with respect to multiple features.

The basic understanding conveyed by the experts in the three practices is that the meditator experiences the goal-states as profound. Wallace notes that the Shamatha goal-state is a “faint facsimile” of enlightenment (pristine awareness) (Wallace, 2011b, p. 121). However, he says that the goal-state is itself “remarkable” (Wallace, 2011b, p. 159) and a “major transformation of consciousness” (Wallace, 1989/2003, p. 150), and can therefore be very easily mistaken for enlightenment. The TM goal-state is frequently described as profound, remarkable, or extraordinary. Meares (1978/1986, p. 26) depicts even the basic Stillness Meditation goal-states as an “experience of the highest order” that “far transcends the ordinary experience of life”. Meares and McKinnon also refer to numerous features of the goal-states, such as the stillness, calm and simplicity, as profound. In TM and Stillness Meditation it is emphasized that the profundity of the experiences is not due to their being flashy, or strange and dramatic. The goal-states are instead described as simple and natural, as discussed above.

Although the basic understanding is that the TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states are profound, there are some indications that this may not always be the case. For example, Roth (2018, p. 45) says that “Sometimes the experience in TM is profound; oftentimes it can seem mundane”. Rosenthal (2016/2017, p. 39), as noted above, describes his and others’ experiences of the TM goal-state/s as “pleasant but unsensational”. In McKinnon (2011, p. 164) it is noted that, having emerged from the Stillness Meditation goal-states, some meditators may query whether such a simple experience can lead to the benefits referred to in that tradition. If meditators were always experiencing the goal-states as profound, it seems curious that they would have that query.

One way of understanding the TM and Stillness Meditation descriptions in the paragraph above is that they refer to shallower goal-states that are not experienced as profound. Another possibility is that all of the goal-states are profound, and that, although the non-profound experiences are sometimes presented as goal-states, they are in fact interim-states. It is not clear from the extracted text which of these understandings is correct, or whether they both apply to some degree.

2.16 Group 16 – attention

Wallace indicates that in the Shamatha goal-state attention is on what he variously describes as the emptiness, vacuity, absence of appearances, quiescence, mind, and consciousness. The TM experts state similarly that in the TM goal-state attention is on what they refer to as consciousness or mental silence. It is clear from the Shamatha and TM passages that the experts are using the different terms such as emptiness, consciousness and silence to refer to what is being experienced as a whole. When they say, for example, that attention is on the silence, they mean that attention is on what is being experienced overall, including emptiness, silence, and so on, not that attention is on the silence as a specific facet of the overall experience. For clarity, in the discussions concerning attention in the remainder of this paper, we will refer to what is being experienced overall as the emptiness/silence.Footnote 15

When addressing the Stillness Meditation goal-states within the discussions, we will, for simplicity, deal only with the deeper goal-states, where even very dull perceptions are absent. The Stillness Meditation experts do not expressly state that attention is on the emptiness/silence. However, as in Shamatha and TM, in the Stillness Meditation goal-states the meditator is said to experience the emptiness/silence alone, without everyday content. That implies that the meditator’s attention is on the emptiness/silence, like in Shamatha and TM.

The next point to consider is the nature or quality of the attention on the emptiness/silence in the three practices. In the Shamatha goal-state the meditator is said to have “exceptional” (Wallace, 2006a, p. 159) or “perfect” (Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 212) stability and vividness of attention. The exceptional stability is such that attention can remain on the emptiness/silence for four or more hours without the slightest deviation (Wallace, 1989/2003, p. 196, 2011b, p. ix). Another way of describing this stability is by saying that attention is focused on the emptiness/silence “single-pointedly like a laser” (Wallace, 2001/2003, p. 133). Wallace states that traces of everyday content may occasionally arise, but he indicates that this only occurs where the meditator fails to maintain single-pointed attention (Wallace, 2006a, p. 161; Wallace & Hodel, 2008, p. 212). Since he presents single-pointed attention as a key feature of the Shamatha goal-state, in this analysis we will assume that it is maintained. Exceptional vividness means that the emptiness/silence is experienced with perfect clarity or focus, without even the slightest dullness (SH 1.5.4, 1.7.3, 2.14.27; Wallace, 1989/2003, p. 196).

In Shamatha, the meditator cultivates the exceptional stability and vividness methodically over the course of the interim-states. They develop the stability principally by eliminating excitation, and the vividness by overcoming laxity/dullness. The main way to counteract excitation is to relax, and the main antidote to dullness is to arouse attention. The exceptional stability and vividness of the goal-states can be maintained without effort (Wallace, 2011b) because they have been cultivated methodically.

For a meditator who has reached the TM or Stillness Meditation goal-state/s, a meditation session is said to involve repeatedly moving into and out of that experience. In TM this is referred to as “cycling” in and out (Faber et al., 2017, p. 313; Travis, 2011, p. 229), and in Stillness Meditation it is characterized as an “ebb and flow” (McKinnon, 1983/2016, p. 221; Meares, 1989, p. 17). Within a meditation session, the movement out of the goal-state/s is said to be beyond the meditator’s control, but with continued practice it tends to occur less frequently, meaning that the periods in the goal-state/s lengthen.

Where the TM or Stillness Meditation practitioner is able to stay in the goal-state/s for extended periods, this implies a degree of stability in the experience of the emptiness/silence. However, the fact that experienced meditators will still move out of the goal-state/s multiple times in a session indicates that there is substantially less stability than in Shamatha. Movement out of the goal-state/s occurs where the meditator experiences everyday content. That appears to entail the meditator’s attention moving from the emptiness/silence to that content to some degree.

The lesser stability in TM and Stillness Meditation fits with the understanding that the Shamatha meditator develops single-pointed attention by cultivating it methodically in the interim-states. It is clear from the TM and Stillness Meditation accounts that the cultivation of single-pointed attention is not part of those practices (see Woods et al., 2022a). In Stillness Meditation the meditator makes no effort to focus attention. In TM, the meditator brings attention to the mantra to prompt the mind to move automatically towards the goal-state/s. After that initial prompting, any deliberate focusing of attention is abandoned.Footnote 16 The goal-states in the two practices are in places referred to as involving an absence of focus.

The TM and Stillness Meditation experts tend not to use the terms vivid or vividness in describing the goal-states. However, in both practices the goal-states are said to involve clarity, and to be clear or “crystal clear” (Meares, 1983a, p. 118; Pearson, 2013, p. 26). In most places there is ambiguity as to whether the experts use these terms to refer to vividness or to the absence of everyday content. In cases, though, Meares (1983a, p. 118, 1987a, p. 34, 1987/1991, p. 114) juxtaposes the terms with drowsiness, which suggests that, at least in those passages, he is using them to refer to vividness.

The Shamatha meditator eliminates dullness through active, careful, and systematic efforts to arouse attention. The efforts to arouse attention in TM and Stillness Meditation are much more limited. In Stillness Meditation there is no effort to arouse attention, other than by maintaining a degree of discipline in the posture (see Woods et al., 2022a). TM involves a degree of arousal in bringing attention to the mantra, but beyond that the emphasis is on abandoning any attempt to focus attention (see above).

These observations give the clear impression that TM and Stillness Meditation do not entirely eliminate dullness, and this leads to the understanding that the Shamatha goal-state involves substantially greater vividness. The vividness in TM and Stillness Meditation may be high according to standards from normal waking life, but the impression is that it is moderate or low in comparison to the perfect vividness in Shamatha.

The final feature of the goal-states for consideration in this section is attentional balance, which is a construct used only in the Shamatha accounts. The Shamatha goal-state is described as involving exceptional attentional balance in that “a high level of attentional arousal is maintained simultaneously with deep calm and relaxation” (Wallace, 2012/2014, p. 166). The TM and Stillness Meditation goal-states are said to involve deep calm and relaxation like in Shamatha, but they appear to involve considerably less attentional arousal. On this basis it seems that the attentional balance in the Shamatha goal-state is different to that in TM and Stillness Meditation.

2.17 Group 17 – description in words is limited

In each of the three practices the experts indicate that words are somehow limited in their ability to describe the goal-states. Pearson (2013, p. 55) puts this particularly strongly, asserting that the TM goal-state/s are “fundamentally ineffable [or] indescribable”, and “[u]tterly beyond words”. McKinnon (2011, p. 85) states that the Stillness Meditation goal-states are “far, far beyond words”, and Meares (1978/1986, p. 145) says that “[w]ords fail”. Wallace (2018, p. 58) expresses this by saying that “words take [the meditator] a step away from the experience”. He says that words are a “conceptual overlay” on the experience (Wallace, 2000, p. 110), not the experience itself. The basic problem in the three practices seems to be that words typically involve or assume logic, concepts, and subject-object duality, but in this context they are called upon to describe the goal-states, which involve an absence of those qualities (e.g., McKinnon, 2011, pp. 85–86; Meares, 1978/1986, p. 20, 1989, p. 113; Wallace, 2000, p. 110).

The limitation does not mean that nothing can be said about the goal-states. Indeed, the experts describe the goal-states in a great deal of detail, as is clear from this Section 2. As such, when the experts say that the experiences are beyond words, what they seem to mean is that some aspect is beyond words, or, equivalently, that the experiences are beyond words to some extent.

In each practice experts indicate that the gap between the words and the goal-states will be greater for someone who has not had the experience. A meditator who has had the experience will be able to draw on it in giving meaning to the words, and that will result in a reduction in the gap. Wallace indicates that for this reason the Shamatha goal-state is not regarded as ineffable, at least not for experienced meditators (Wallace, 2007a, pp. 79, 82, 2011b, p. 179, 2018, p. 57). Experienced meditators can discuss it with one another in terms that to them are clear and intelligible. The TM and Stillness Meditation experts do not make these points with respect to those practices. It seems hard to imagine, however, that they would argue against the idea that experienced meditators can discuss the goal-states in an intelligible fashion.

2.18 Group 18 – variation within each practice

Wallace generally presents the experience aimed for in Shamatha as a single state, rather than indicating any variation within it. It is the ground-state of consciousness or the mind, and is referred to as unfluctuating. There is, however, one strand of Wallace’s analysis that suggests there could be variation in the experience. Wallace says that, although meditators do not consciously experience any concepts in the goal-state, certain implicit or subliminal conceptualization persists. In one text he notes that differences in meditators’ implicit conceptualization can result in them having “significantly different” experiences of what appears on the surface to be a single state of pure consciousness (Wallace, 2000, p. 118). Although he does not make that statement with respect to the Shamatha goal-state specifically, he gives no reason to think that it would not apply in that context.