Abstract

Background

Gliomas are associated with significant healthcare burden, yet reports of costs are scarce. While many costs are unavoidable there may be treatable symptoms contributing to higher costs. We describe healthcare and societal costs in glioma patients at high risk for depression and their family caregivers, and explore relationships between costs and treatable symptoms.

Methods

Data from a multicenter randomized trial on effects of internet-based therapy for depressive symptoms were used (NTR3223). Costs of self-reported healthcare utilization, medication use, and productivity loss were calculated for patients and caregivers separately. We used generalized linear regression models to predict costs with depressive symptoms, fatigue, cognitive complaints, tumor grade (low-/high-grade), disease status (stable or active/progression), and intervention (use/non-use) as predictors.

Results

Multiple assessments from baseline through 12 months from 91 glioma patients and 46 caregivers were used. Mean overall costs per year were M = €20,587.53 (sd = €30,910.53) for patients and M = €5,581.49 (sd = €13,102.82) for caregivers. In patients, higher healthcare utilization costs were associated with more depressive symptoms; higher medication costs were associated with active/progressive disease. In caregivers, higher overall costs were linked with increased caregiver fatigue, cognitive complaints, and lower patient tumor grade. Higher healthcare utilization costs were related to more cognitive complaints and lower tumor grade. More productivity loss costs were associated with increased fatigue (all P < 0.05).

Conclusions

There are substantial healthcare and societal costs for glioma patients and caregivers. Associations between costs and treatable psychological symptoms indicate that possibly, adequate support could decrease costs.

Trial registration

Netherlands Trial Register NTR3223.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gliomas cause not only a high disease burden that greatly affects patients’ and their family caregivers’ lives, but are also associated with a high healthcare burden [1]. Reports on direct (health and social care) and indirect (e.g., productivity loss due to work absence) costs are scarce and often not comprehensive, but hint towards costs being substantial [2, 3]. Individual indirect costs are higher compared to other brain disorders [3], and a small US study revealed substantial out-of-pocket costs among high-grade glioma patients (N = 43; median $1341 per month) [4]. These studies do not yet take into account social care and support costs often absorbed by family caregivers. Uncompensated caregiving hours do not only result in income loss (between €8124 and €20,196 annually) but also have tangible consequences for caregivers’ careers [5].

Depressive symptoms, fatigue, and cognitive deficits are common symptoms in glioma patients and may impact on patients’ and family caregivers’ quality of life [6,7,8]. But, these symptoms may also impact on direct and indirect costs. Depressive symptoms and fatigue have been linked with an increase in healthcare utilization and reduced work productivity [9,10,11,12]. Indeed, in working adults with malignant brain tumors (N = 131), depressive symptoms, fatigue, and cognitive issues accounted for 65% of the variance in work limitations [13]. Depressive symptoms, alongside cognitive issues, were predictive of difficulty performing at work and greater loss of productivity in patients with skull base tumors (N = 45) [14]. Despite the poor evidence-base for effectiveness of support in this population [15,16,17], depressive symptoms, cognitive deficits, and fatigue are potentially treatable symptoms.

Most brain tumor specific studies described above were carried out in the US, many did not link productivity loss to costs, none have presented patient and caregiver costs in one report, and none have investigated the relationship between costs and potentially reversible symptoms. We therefore aimed not only to describe costs in glioma patients and family caregivers, but also to explore associations between patients’ and caregivers’ depressive symptoms, fatigue, cognitive complaints and both patient and caregiver costs during a 12 month period. More knowledge on the costs associated with potentially treatable symptoms in a population with disproportionately high burden, will strengthen the case for further investigation of effectiveness of support programs to improve the lives of patients and family caregivers.

Methods

Participants

Patient-caregiver dyads were invited to participate in a Dutch nation-wide randomized controlled study to investigate the effectiveness of an internet-based guided self-help intervention in glioma patients with depressive symptoms [18, 19]. Recruitment procedures have been described in more detail elsewhere [18, 19]. Adult (> 18 years of age) glioma patients with WHO grade II, III or IV glioma, and at least mild depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥ 12) were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria were (1) no access to the internet and/or no email address; (2) insufficient proficiency of the Dutch language; (3) suicidal intent. All patients were asked to invite a family caregiver (defined as the person providing the majority of mental and physical support) to participate. Participants were recruited between November 2011 and June 2015, with 95 of the 114 glioma patients expressing interest and meeting all inclusion criteria signing written informed consent (83.3%). Details on reasons for declining participation are not available.

Procedures

Following consent procedures, assessments consisting of online questionnaires took place at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 18 weeks, 24 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months [19]. Patients and caregivers reported on their own experiences. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the VU University Medical Center (Registration Number 2011/227), and was registered in the Netherlands Trial Registry (NTR3223).

Outcome measures

The Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TIC-P) [20] was administered, which incorporates the Short-Form Health and Labor Questionnaire (SF-HLQ) [21]. It covers the direct costs of healthcare utilization from appointments and medication (including oral chemotherapy, but excluding procedures such as surgery and/or radiotherapy), and indirect costs due to productivity loss in three modules: absence from paid employment; production loss without absence from paid employment; and impediments to paid or unpaid employment. Further outcome measures included: the Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [22] for depressive symptoms; the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) [23] for fatigue; the MOS cognitive functioning scale [24] for cognitive complaints; and the EORTC Brain Cancer Module [25] for disease-specific symptoms (patients only).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA (v. 15) and SPSS software (v. 23). Medication costs per four weeks were calculated based on the Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) from the 2015 GIP databank, with €6 added per case to account for pharmacy prescription costs and a further 6% for taxes. Costs for healthcare utilization per four weeks were calculated based on the values published in the updated 2015 Cost Manual [26], plus travel and parking costs as appropriate. Costs for productivity loss (presenteeism and absenteeism per four weeks) were derived from the SF-HLQ, with €34.75 per working hour and €14 for each hour of unpaid work as recommended in the updated Cost Manual [26]. A total cost variable was calculated by adding costs for medication, healthcare utilization, and productivity loss. The inflator from 2015 to 2019 is 1.06 as per the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group/Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre Cost Converter [27], hence all costs were multiplied by 1.06.

Descriptive statistics were generated for sociodemographic characteristics, and baseline assessments of healthcare utilization, productivity loss, depressive symptoms (CES-D), fatigue (CIS), cognitive complaints (MOS), and costs in patient and caregiver groups. As cost data has a positively skewed distribution, we used generalized linear regression models (gamma family, log link) to identify statistically significant explanatory variables. We used multiple observations per participant (baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 18 weeks, 24 weeks, 6 months, 12 months) and robust standard errors based on participant to account for this. We included patients’ and caregivers’ self-reported depressive symptoms (CES-D), fatigue (CIS), and cognitive complaints (MOS) as potentially reversible symptoms. We included tumor grade (low-/high-grade) and disease status (stable/progression/active treatment) to cover important clinical differences within individuals. In patients only, intervention (use/non-use) was included to account for potential impact of the internet-based therapy—caregivers did not undergo any intervention. Variables associated at P < 0.10 and those of theoretical importance providing improvement in model fit were included in a multivariate model with backward selection to yield final prediction models, based on best fit according to the Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria. We derived marginal effects for the included covariates and here, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data were not imputed, and no corrections for multiple testing were made due to the exploratory nature of the project.

Results

Participants

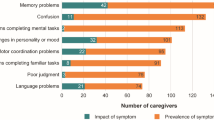

In total, 90 patients (291 observations) and 45 family caregivers (95 observations) completed at least one assessment and were included. Average age was 45 for patients and 48 for caregivers, see Table 1. More than half of patients were women (58.9%) and 53.5% of caregivers were men. 55.6% of patients were diagnosed with a WHO grade II glioma, and on average, patients were diagnosed 3.44 (sd = 4.84, range 0–26) years prior to enrolment. Nearly all caregivers were the patient’s spouse/partner (86.7%). Both patient and caregiver groups had relatively high baseline scores for depressive symptoms (patients M = 23.61, sd = 6.37; caregivers M = 17.16, sd = 6.34).

Description of costs at baseline

Overall direct and indirect costs

At baseline, on average, the total direct and indirect costs per 4 weeks amounted to M = €1604.43 (sd = €2377.73) for patients and M = €429.34 (sd = €1007.91) for caregivers. On a yearly basis this translates to M = €20,857.53 (sd = €30,910.53) for patients and M = €5581.49 (sd = €13,102.82) for caregivers. This is broken down into separate costs for healthcare utilization, medication, and productivity loss as described below.

Healthcare utilization and medication

Healthcare service use per four weeks yielded a total per patient cost of M = €422.94 (sd = €912.84, see Table 2). Outpatient specialist care (33.3%) and GP services (31.1%) were accessed most regularly. Psychology or psychiatry services (other than the internet-based therapy tested), were used by 26.7% of patients. Home care services were used with highest frequency per service user (up to 56 contacts in four weeks, or twice a day). Medication was used by nearly all patients (90.0%) and was associated with an average cost of €107.95 (sd = €203.43, range €0–€1148.14) per four weeks. The majority of patients (77.8%) used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), for which the DDD ranged between €0.11 (phenytoin) to €5.38 (lacosamide), with many taking multiple drugs concurrently. Some patients were taking chemotherapeutic drugs, often in combination (12.2%) for which the DDD ranged between €3.88 (lomustine) and €17.63 (vincristine).

For caregivers, average costs associated with healthcare service use per four weeks were M = €142.21 (sd = €397.01). About a fifth of caregivers (21.2%) had visited their GP, and 13.3% had attended an outpatient hospital appointment. Psychology or psychiatry services were accessed by 20.0% of caregivers. Home care services were used with highest frequency per service user (up to 22 visits in four weeks). Medication was used by 48.9% of caregivers with an average cost of €14.13 (sd = €22.54) per four weeks.

Productivity loss

At baseline, over a third of patients reported to be in paid employment (37.4%). Others described their productivity status as being declared unfit for work (in whole or in part, 41.1%), taking primary care of the household (13.3%), retired (5.6%), student (3.3%), or ‘other’ (11.1%). Many reported to be hindered by health problems in everyday tasks: domestic work (54.4%), grocery shopping (45.6%), chores around the house (44.4%), and taking care of children (24.4%). Absenteeism was reported by 48.9% of patients, and presenteeism (productive hours lost while working) by another 7.8%. Together, the costs for productivity loss were M = €1264.95 (sd = €2299.97) per patient (employed and unemployed) per four weeks.

Most caregivers reported they were in paid employment at baseline (66.7%). Others were retired (13.3%), declared unfit for work (in whole or in part, 6.7%), taking primary care of the household (2.2%), or reported ‘other reasons’ (4.4%). A minority of caregivers reported to have been hindered by health issues in domestic work (6.7%), grocery shopping (8.8%), chores (6.7%), or child care (4.4%). Absenteeism was reported by 24.4% of caregivers, and presenteeism by another 6.7%. In total, productivity loss in caregivers was on average €337.42 (sd = €901.15) per four weeks.

Associations between costs and treatable psychological symptoms

Glioma patients

All significant associations based on univariate and multivariate analysis in patients are shown in Table 3. In univariate analysis of healthcare costs in patients, there were significant associations between increased healthcare utilization costs and increased symptoms of depression (+€18.34 per four weeks with each unit increase in scores); fatigue (+€5.49); and cognitive complaints (+€6.17; all P < 0.05). In the final multivariate model which included depressive symptoms and tumor grade, depressive symptoms remained significantly associated with increased healthcare costs (+€24.46, P = 0.001).

In univariate analysis of medication costs, there were significant associations between higher medication costs and decreased depressive symptoms (−€2.48 per 4 weeks with each unit increase in scores), fewer cognitive complaints (−€1.89), higher tumor grade (+€56.53 for high-grade glioma vs. low-grade glioma), and active disease status (+€117.90 for active disease or progression vs. stable disease; all P < 0.05). The final multivariable model included cognitive complaints, tumor grade and disease stage. Active/progressive disease remained a statistically significant predictor of medication costs (+€76.17 for active/progressive disease vs. stable disease, P < 0.001).

Family caregivers

All significant associations based on univariate and multivariate analysis in caregivers are shown in Table 4. In univariate analysis of overall costs, there were significant associations between higher costs and increased caregiver-reported depressive symptoms (+€14.57), fatigue (+€12.25), cognitive complaints (+€18.29), and patient tumor grade (+€253.72 for low-grade glioma vs. high-grade glioma; all P < 0.10). In the final multivariate model, higher overall costs were associated with increased fatigue (+€5.60) and lower patient tumor grade (−€384.95; all P < 0.05).

In univariate analysis of healthcare utilization costs, there were significant associations with increased caregiver-reported depressive symptoms (+€8.03 per 4 weeks with each unit increase in scores), fatigue (+€3.99), cognitive complaints (+€5.57), and lower patient tumor grade (−€113.43 for high-grade glioma vs. low-grade glioma; all P < 0.05). In the final multivariate model which included cognitive complaints, fatigue, and tumor grade, only increased caregiver-reported cognitive complaints (+€4.80) and lower tumor grade (−€125.81) remained statistically significantly associated with higher healthcare costs (P < 0.05).

Medication costs were significantly associated with lower caregiver depression scores (−€1.15, P = 0.019) only.

In univariate analysis, higher productivity loss costs were significantly associated with increased caregiver-reported depressive symptoms (+€12.80), fatigue (+€21.66), cognitive complaints (+€16.01), and patient tumor grade (−€227.57 for high-grade glioma vs. low-grade glioma; all P < 0.10). The final multivariate model included fatigue, cognitive complaints, and tumor grade: only fatigue (+€5.60) and lower tumor grade (−€384.95) remained significantly associated with increased productivity loss costs (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Very little is known about the true costs of primary brain tumors for patients, caregivers, the healthcare system and society. Our study is one of the first to provide meaningful quantitative data by focusing on the costs associated with self-reported healthcare utilization, medication, and productivity loss of glioma patients and caregivers. The healthcare costs measured excluded most anti-tumor procedures, but included adjuvant chemotherapy—thus essentially reflect maintenance costs only. We found that on average 3 years after diagnosis, healthcare utilization, medication use, and productivity loss resulted in yearly costs of M = €20,857.53 in glioma patients at high risk for depression; with an additional yearly cost of M = €5581.49 in family caregivers. Overall yearly costs per dyad (€26,439.02) approaches the yearly Dutch median income per household [28].

Costs varied greatly between participants as evidenced by the large standard deviations. Interestingly, while only 1/3rd of patients and 2/3rds of caregivers were in paid employment, productivity loss costs accounted for > 78% of costs. Of note, most costs are not directly absorbed by patient-caregiver dyads. Rather, costs are divided evenly across the Dutch population through the social security system, and thus reflect a societal cost rather than a personal cost.

Many consequences of brain tumors are unavoidable or difficult to manage. We therefore investigated associations between those symptoms that are potentially reversible (depressive symptoms, fatigue, cognitive complaints) and costs. Despite being a patient-caregiver group at high risk for depression, less than a quarter of participants had accessed psychology/psychiatry services. In patients, reversible symptoms were not very strongly related to costs: in multivariate analyses, increased healthcare costs were associated with increased depressive symptoms. The association between medication costs and cognitive complaints approached statistical significance. In part, this could be explained by the relative homogeneity of our patient sample, as all were at increased risk of depression. Previous studies found associations between depressive symptoms, fatigue, cognitive complaints, and work limitations [13, 14]. Work limitations reflect a person’s experienced difficulty in managing time and demands rather than costs from presenteeism/absenteeism—which does not necessarily overlap.

In caregivers, higher overall costs were linked with increased fatigue and cognitive complaints; higher healthcare utilization costs were related to more cognitive complaints; and higher productivity loss costs were associated with increased fatigue. As caregivers did not suffer from a direct physical cause of cognitive complaints, these may have been an indirect consequence of increased burden. Our results seem to confirm the large role of fatigue in work productivity found in the general working age population [12]. Interestingly, depressive symptoms seemed to impact less than expected [9,10,11]. Some caution is warranted when interpreting these findings, as these are based on a small sample size, and in some cases show statistical significance despite having 0 in the 95% confidence interval. Lower tumor grade was predictive of higher costs in our caregiver sample. Compared to patients with more aggressive brain tumors, low-grade glioma patients survive for longer, more frequently suffer from epilepsy, and are relatively young with often young families and a busy working life. Our findings confirm the high social impact and financial toxicity of low-grade glioma from the caregiver perspective. Helping caregivers cope better can potentially reduce overall costs associated with brain tumors by over 20%. If not properly supported, costs could increase over time as prolonged periods of stress and poorer self-care in caregivers can lead to poor physical health effects [29, 30].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study are the detailed self-reported use of healthcare services, medications, and productivity loss parameters; the longitudinal nature of the data; and our robust modelling techniques. Our analyses are exploratory and not corrected for multiple testing. The self-report nature of the data may have introduced some bias, leading to over- or underestimation of costs. For example, productivity loss costs are based on self-reported absence or reduced productivity—which may not completely overlap with an employer’s records. Finally, our patients were at high risk for depression, thus findings may not be generalizable to all glioma patient-caregiver populations. However, the RCT was intended to have high external validity and thus few exclusion criteria were employed. This is reflected in a relatively heterogeneous sample of glioma patients in terms of grade, localization, and treatment, as well as the reasons for attrition (which include e.g., cognitive issues, relief of symptoms, and disease progression [18]).

Conclusions

Nevertheless, we were able to show that potentially treatable symptoms are linked with higher healthcare utilization costs in patients, and higher overall costs, healthcare utilization costs, and productivity loss in caregivers. More generally, we demonstrated that healthcare service and medication use, and productivity loss costs for patient-caregiver dyads are substantial and vary greatly between individuals. This study provides evidence that the true cost of brain tumors is a burden shared between patients, caregivers, the healthcare system, and society as a whole.

References

Messali A, Villacorta R, Hay JW (2014) A review of the economic burden of glioblastoma and the cost effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments. Pharmacoeconomics 32:1201–1212

Raizer JJ, Fitzner KA, Jacobs DI, Bennett CL, Liebling DB, Luu TH, Trifilio SM, Grimm SA, Fisher MJ, Haleem MS (2014) Economics of malignant gliomas: a critical review. J Oncol Pract 11:e59–e65

Fineberg NA, Haddad PM, Carpenter L, Gannon B, Sharpe R, Young AH, Joyce E, Rowe J, Wellsted D, Nutt DJ (2013) The size, burden and cost of disorders of the brain in the UK. J Psychopharmacol 27:761–770

Kumthekar P, Stell BV, Jacobs DI, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Grimm SA, Bennett CL, Raizer JJ (2014) Financial burden experienced by patients undergoing treatment for malignant gliomas. Neuro-oncol Pract 1:71–76

Bayen E, Laigle-Donadey F, Prouté M, Hoang-Xuan K, Joël M-E, Delattre J-Y (2017) The multidimensional burden of informal caregivers in primary malignant brain tumor. Support Care Cancer 25:245–253

Taphoorn MJB, Klein M (2004) Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumors. Lancet Neurol 3:159–168

Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, Hagen N (2002) Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol 57:41–49

Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Schiffman RF, Murman DL, Lovely M, von Eye A, Rogers LR, Remer S (2006) Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Res Nursing Health 29:105–120

Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, Berndt ER, Irish JT, Lapitsky L, Hood MY, Reed J, Rogers WH (2004) The clinical and occupational correlates of work productivity loss among employed patients with depression. J Occup Environ Med 46:S46

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D (2003) Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 289:3135–3144

Vamos EP, Mucsi I, Keszei A, Kopp MS, Novak M (2009) Comorbid depression is associated with increased healthcare utilization and lost productivity in persons with diabetes: a large nationally representative Hungarian population survey. Psychosom Med 71:501–507

Ricci JA, Chee E, Lorandeau AL, Berger J (2007) Fatigue in the US workforce: prevalence and implications for lost productive work time. J Occup Environ Med 49:1–10

Feuerstein M, Hansen JA, Calvio LC, Johnson L, Ronquillo JG (2007) Work productivity in brain tumor survivors. J Occup Environ Med 49:803–811

Nugent BD, Weimer J, Choi CJ, Bradley CJ, Bender CM, Ryan CM, Gardner P, Sherwood PR (2014) Work productivity and neuropsychological function in persons with skull base tumors. Neuro-oncology Pract 1:106–113

Rooney A, Grant R (2013) Pharmacological treatment of depression in patients with a primary brain tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:CD006932

Day J, Yust-Katz S, Cachia D, Wefel J, Katz L, Tremont I, Bulbeck H, Armstrong T, Rooney A (2016) Interventions for the management of fatigue in adults with a primary brain tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD011376

Day J, Zienius K, Gehring K, Grosshans D, Taphoorn M, Grant R, Li J, Brown P (2014) Interventions for preventing and ameliorating cognitive deficits in adults treated with cranial irradiation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD011335

Boele FW, Klein M, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Cuijpers P, Heimans JJ, Snijders TJ, Vos M, Bosma I, Tijssen CC, Reijneveld JC (2018) Internet-based guided self-help for glioma patients with depressive symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurooncol 137:191–203

Boele FW, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Cuijpers P, Reijneveld JC, Heimans JJ, Klein M (2014) Internet-based guided self-help for glioma patients with depressive symptoms: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol 14:81

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Straten Av, Tiemens B, Donker MCH (2002) Handleiding Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric illness (TiC-P)

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Bouwmans CAM, Rotterdam EU (2009) Short Form-Health and Labour Questionnaire. Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre, Rotterdam (2007). https://www.imta.nl/publications/07103.pdf

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401

Vercoulen JHM, Alberts M, Bleijenberg G (1999) De Checklist Individuele Spankracht (CIS). Gedragstherapie 32:131–136

Steward AL, Ware JE (1992) Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Duke University Press, Durham

Taphoorn MJ, Claassens L, Aaronson NK, Coens C, Mauer M, Osoba D, Stupp R, Mirimanoff RO, van den Bent MJ, Bottomley A (2010) An international validation study of the EORTC brain cancer module (EORTC QLQ-BN20) for assessing health-related quality of life and symptoms in brain cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 46:1033–1040

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Van der Linden N, Bouwmans C, Kanters T, Tan SS (2015) Kostenhandleiding. Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg In opdracht van Zorginstituut Nederland Geactualiseerde versie

Shemilt I (2019) The Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group (CCEMG) and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) Cost Converter. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/.

StatLine CBoS (2018) Household income; income classes; household characteristics. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83932NED/table?ts=1560508876997

Schulz R, Visintainer P, Williamson GM (1990) Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of caregiving. J Gerontol 45:P181–P191

Sherwood P, Price T, Weimer J, Ren D, Donovan H, Given C, Given B, Schulz R, Prince J, Bender C, Boele F, Marsland A (2016) Neuro-oncology family caregivers are at risk for systemic inflammation. J Neurooncol 128:109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-016-2083-3

Acknowledgements

We thank the Dutch Society for Neuro-Oncology and neurologists, neurosurgeons, oncologists, pathologists and nurses from all participating centers for their help in recruiting participants for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society, Alpe d’HuZes (VU 2010-4808). The first author was supported by a Yorkshire Cancer Research University Academic Fellowship (L389FB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IMVdL, JJH, JCR and MK designed the trial which formed the basis for this project. FWB, DM, and FJ designed the secondary data analysis project. FWB coordinated the trial, and led participant recruitment and data collection. FWB and DM performed the data analysis. All authors advised on data analysis and interpretation. FWB wrote the first draft of the Article, which was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest exists for any author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boele, F.W., Meads, D., Jansen, F. et al. Healthcare utilization and productivity loss in glioma patients and family caregivers: the impact of treatable psychological symptoms. J Neurooncol 147, 485–494 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03454-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03454-3