Abstract

Spanish hypocoristics are usually bisyllabic and sometimes bimoraic. In this paper we study a process of truncation in Spanish that results in trisyllabic hypocoristics (Encárna ← Encarnación, Mariájo ← María José). Trisyllabic hypocoristics usually surface with amphibrach (weak-strong-weak) rhythm (Encárna ← Encarnación), although some forms show anapest (weak-weak-strong) rhythm (Marijó ← María José). This article develops an analysis of this process by means of internally layered ternary feet. Internally layered feet are binary feet to which a weak syllable adjoins to create a minimally recursive foot. The theoretical claim of this paper is twofold: (i) that Spanish trisyllabic truncated forms correspond to an internally layered foot, which reconciles the general assumption that truncated forms maximally correspond to the size of a metrical foot, and (ii) that morphological operations such as truncation can directly refer to internally layered feet, expanding the body of work on layered feet by Martínez-Paricio and Kager (2015). Overall, the analysis presented in this article explores a less studied theoretical and descriptive advantage of this ternary metrical configuration (i.e. its templatic use) and provides new evidence in support of layered feet as a possible metrical representation which emerges in some languages from independently needed constraints.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

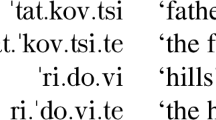

Throughout the paper examples are given in their orthographic form, syllable boundaries are marked with dots, foot boundaries are marked with parentheses, and stressed syllables are marked with an acute accent, even though this sometimes contravenes orthographic rules. Orthographic <i, u> when adjacent to another vowel within the same syllable must be interpreted as a glide (e.g. Ma.nuél should be interpreted as [ma.'nwel]; En.car.na.ción, as [en.kaɾ.na'Ɵjon]) vs. Ma.rí.a, interpreted as [ma.'ri.a], where the high vowel is the nucleus of its own syllable.

An anonymous reviewer points out that the forms in (3) could be analyzed as containing a disyllabic foot plus a (gender or theme vowel) suffix rather than being analyzed as clear examples of trisyllabic templates. Regardless of the internal morphological structure of these forms, we believe along the lines of Felíu (2001) that the forms in (3) constitute clear examples of trisyllabic TFs (henceforth TTFs). Note that whereas in some of these TFs the final vowel is a gender suffix or theme vowel (e.g. análf-a, maníf-a), this is not possible for all the documented TFs: in indépe and colégui there is no clear suffix. Hence a purely trisyllabic template seems to be active in the language (the unmarked morphs for masculine and feminine in Spanish are -o and -a, respectively; see Bonet 2006 for a study of gender desinences in Spanish).

The examples in (5a, b) contain an ILT foot which arises from the adjunction of a light syllable to a syllabic trochee (5c). However, ILT feet may equally arise from the adjunction of a syllable to other foot types, such as iambs or moraic trochees.

For a different analysis of these facts with improper bracketed metrical structures (i.e. ambipodal syllables), see Hyde (2002).

It is true that there are no stress-anchored TTFs in Spanish without a suffix, but we believe that this is just an accidental gap in the typology. Note that for a stress-anchored TTF with no suffix to exist, two types of SFs would be required: (i) names with antepenultimate stress that end in a consonant, that is, with no suffix (e.g. CV.'CV.CV.CVC), or (ii) names at least four-syllables long with penultimate stress (e.g. CV.CV.'CV.CVC). In the first case, stress shift would occur in order to comply with the unmarked amphibrach rhythm of TTFs (e.g. 'CV.CV.CVC → CV.'CV.CVC), similar to the stress shift found in bisyllabic TFs derived from SFs with an iambic pattern (Jóse ← José). In the second case, there would be truncation of the syllable(s) up to the third-to-last syllable of the SF (e.g. CV.CV.'CV.CVC → CV.'CV.CVC). In Spanish, antepenultimate stress in forms with a final closed syllable is rare, and we have found no name in Spanish with such a profile. Also, names with penultimate stress that end in a consonant exist (e.g. Ángel, César, Cristóbal) but none is longer than three syllables. Therefore, the absence of stress-anchored TTFs with no suffix seems to be just an accident.

Recall that a high vowel adjacent to another vowel in the same syllable is realized as a glide (e.g. Ma.r[j]a.jo.sé).

An anonymous reviewer suggests an alternative analysis for all compound-based TFs as derived from monosyllabic and bisyllabic templatic base forms, just as we assume for four-syllable truncate-based compounds. All combinations of compound hypocoristics formed of one- and two-syllable templates would be attested: 1σ+1σ = Juán+Ma ← Juán María; 1σ+2σ = Juan+Dávi ← Juán Davíd; 2σ+1σ = Teré+Lu ← Terésa Lóurdes; 2σ+2σ = Mari+Féli ← María Felísa. Under this view, trisyllabicity would emerge as an epiphenomenon of template compounding. This is a very attractive analysis. However, monosyllabic templates consisting of a light syllable like *Lú are not attested in Spanish in isolation, and they should therefore be circumscribed to compounds of this type.

See Alber and Arndt-Lappe (2012) for an investigation of the role of Anchor constraints in the typology of truncation patterns.

This distinction is not crucial for our analysis, but we maintain it for coherence with previous work.

The analysis presented here would work equally well if Parse-Syll were to be used instead of Chain-Right and Chain-Left. However, given that these constraints are independently needed to account for the typology of rhythmic stress systems, we have also adopted them here to account for the shape of hypocoristic TFs.

The constraint Trochee\(_{Nonmin}\) has the same effect as Ft-Bin. The former penalizes ILT feet with a left adjunct, and the latter penalizes all types of ILT feet. We omit Trochee\(_{Nonmin}\) and only use Ft-Bin for the sake of simplicity.

An anonymous reviewer suggests analyzing such a pattern of anapest hypocoristics as atemplatic, involving double anchoring to the first and stressed syllable of the SF, a productive pattern described for vocative truncation in Southern Italian dialects and Sardinian that yields truncated vocatives of variable size (Alber 2010); some examples in Sardinian are Má! ← Mári; Ma.rí! ← María; Ser.va.tó! ← Servatóre; E.le.o.nó! ← Eleonóra (Cabré and Vanrell 2013).

Penélope Cruz has sometimes been called Pé, although subminimal TFs are banned in Spanish.

Recall that forms like Marivícky are truncate-based compounds, but not single TFs. Michael Kenstowicz warns us about the existence of four-mora truncations in Japanese applied to English loanwords (e.g. rihabiri ← rihabiriteesyon ‘rehabilitation’, asupara ← asuparagasu ‘asparagus’ (Itô 1990). Similar to our truncate-based compounds, these longer truncated forms in Japanese are analyzed in Itô (1990) as a template consisting of two bimoraic feet, instead of a template consisting of four moras.

References

Alber, Birgit. 2010. An exploration of truncation in Italian. In Rutgers working papers in linguistics, eds. Peter Staroverov, Aaron Braver, Daniel Altshuler, Carlos Fasola, and Sarah Murray, Vol. 3, 1–30.

Alber, Birgit, and Sabine Arndt-Lappe. 2012. Templatic and subtractive truncation. In The morphology and phonology of exponence, ed. Jochen Trommer, 289–325. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alderete, John. 1999. Head dependence in stress-epenthesis interaction. In The derivational residue in phonological Optimality Theory, eds. Ben Hermans and Marc van Oostendorp, 29–50. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bakovic, Eric. 2016. Exceptionality in Spanish stress. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 15: 9–25.

Bárkányi, Zsuzsanna. 2002. A fresh look at quantity sensitivity in Spanish. Linguistics 40 (2): 375–394.

Bennett, Ryan. 2012. Foot-conditioned phonotactics and prosodic constituency. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Bennett, Ryan. 2013. The uniqueness of metrical structure: Rhythmic phonotactics in Huariapano. Phonology 30 (3): 355–398.

Benua, Laura. 1995. Identity effects in morphological truncation. In Papers in Optimality Theory. Vol. 18 of University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers, eds. Jill N. Beckman, Suzanne Urbanczyk, and Laura Walsh Dickey, 77–136. Amherst: GLSA.

Bonet, Eulàlia. 2006. Gender allomorphy and epenthesis in Spanish. In Optimality-Theoretic studies in Spanish phonology, eds. Fernando Martínez-Gil and Sonia Colina, 312–338. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Breteler, Jeroen. 2017. Deriving bounded tone with layered feet in Harmonic Serialism: The case of Saghala. Glossa 2 (1): 1–38.

Breteler, Jeroen, and René Kager. 2017. Layered feet laid bare in Copperbelt Bemba tone. In 2016 Annual meeting on phonology, eds. Karen Jesney, Charlie O’Hara, Caitlin Smith, and Rachel Walker, 1–8.

Caballero, Gabriela. 2008. Choguita Rarámuri (Tarahumara) phonology and morphology. PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Caballero, Gabriela. 2011. Morphologically conditioned stress assignment in Choguita Rarámuri. Linguistics 49 (4): 749–790.

Cabré, Teresa. 1993. Estructura gramatical i lexicó: El mot mínim català. PhD diss., Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Cabré, Teresa. 1994. Minimality in the Catalan truncation process. Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics 4: 1–21.

Cabré, Teresa. 1998. Faithfulness to prosodic edges. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 6: 7–22.

Cabré, Teresa, and Michael Kenstowicz. 1995. Prosodic trapping in Catalan. Linguistic Inquiry 26 (4): 694–705.

Cabré, Teresa, and Maria del Mar Vanrell. 2013. Entonació i truncament en els vocatius romànics. In 26è congrés de lingüística I filologia Romàniques, eds. Emili Casanova and Cesáreo Calvo, 543–553. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Colina, Sonia. 1996. Spanish truncation processes: The emergence of the unmarked. Linguistics 34 (6): 1199–1218.

Das, Shyamal. 2001. Some aspects of the phonology of Tripura Bangla and Tripura Bangla English. PhD diss., CIEFL Hyderabad.

Davis, Stuart. 2005. Capitalistic v. militaristic: The paradigm uniformity effect reconsidered. In Paradigms in phonological theory, eds. Laura J. Downing, T. Alan Hall, and Renate Raffelsiefen, 107–121. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davis, Stuart, and Mi-Hui Cho. 2003. The distribution of aspirated stops and /h/ in American English and Korean: An alignment approach with typological implications. Linguistics 41 (4): 607–652.

Dixon, Robert M. W. 1981. Wargamay. In Handbook of Australian languages, eds. Robert M. W. Dixon and Barry J. Blake, 25–170. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Eisner, Jason. 1997. What constraints should OT allow? handout from paper presented at the 71st annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, Chicago. Available as ROA-204 from the Rutgers optimality archive.

Face, Timothy L. 2004. Perceiving what isn’t there: Non-acoustic cues for perceiving Spanish stress. In Laboratory approaches to Spanish phonology, ed. Timothy L. Face, 117–142. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Face, Timothy L. 2006. Cognitive factors in the perception of Spanish stress placement: Implications for a model of speech perception. Linguistics 44 (6): 1237–1267.

Felíu, Elena. 2001. Output constraints on two Spanish word-creation processes. Linguistics 39 (5): 871–891.

Gordon, Matthew. 2002. A factorial typology of quantity-insensitive stress. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20 (3): 491–552.

Grau Sempere, Antonio. 2006. Conflicting quantity patterns in Ibero-Romance prosody. PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Grau Sempere, Antonio. 2013. Reconsidering syllabic minimality in Spanish truncation. ELUA: Estudios de Lingüística. Universidad de Alicante 27: 121–143.

Harris, James W. 1983. Syllable structure and stress in Spanish. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harris, John. 2013. Wide-domain R-effects in English. Journal of Linguistics 49 (2): 329–365.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Hualde, José I. 2005. The sounds of Spanish. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.

Hyde, Brett. 2002. A restrictive theory of metrical stress. Phonology 19 (3): 313–359.

Iosad, Pavel. 2016. Prosodic structure and suprasegmental features. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 19 (3): 221–268.

Itô, Junko. 1990. Prosodic minimality in Japanese. In Papers from the parasession on the syllable in phonetics in phonology. Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 26, Vol. 2, 213–239.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2007. Prosodic adjunction in Japanese compounds. In Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics (FAJL) 4, eds. Yoichi Miyamoto and Masao Ochi. Vol. 55 of Cambridge: MIT working papers in linguistics, 97–111.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2013. Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua 124: 20–40.

Jensen, John T. 2000. Against ambisyllabicity. Phonology 17 (2): 187–235.

Kager, René. 2001. Rhythmic directionality by positional licensing. handout of paper presented at the 5th Holland Institute of Linguistics phonology conference, Potsdam. Available as ROA-514 from the Rutgers optimality archive.

Kager, René. 2007. Feet and metrical stress. In The Cambrdige handbook of phonology, ed. Paul De Lacy, 195–227. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.

Kager, René. 2012. Stress in windows: Language typology and factorial typology. Lingua 122: 1454–1493.

Leer, Jeff. 1985. Prosody in Alutiiq (the Koniag and Chugach dialects of Alaskan Yupik. In Yupik Eskimo prosodic systems: Descriptive and comparative studies, ed. Michael Krauss, 77–133. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Center.

Lipski, John M. 1995. Spanish hypocoristics: Towards a unified prosodic analysis. Hispanic Linguistics 6/7: 387–434.

Martínez-Paricio, Violeta. 2012. Superfeet as recursion. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 30, eds. Nathan Arnett and Ryan Bennett, 259–269. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Martínez-Paricio, Violeta. 2013. An exploration of minimal and maximal metrical feet. PhD diss., University of Tromsø–Arctic Universtity of Norway.

Martínez-Paricio, Violeta, and René Kager. 2015. The binary-to-ternary rhythmic continuum in stress typology: Layered feet and non-intervention constraints. Phonology 32 (3): 459–504.

McCarthy, John J. 2000. Faithfulness and prosodic circumscription. In Optimality Theory: Phonology, syntax, and acquisition, eds. Joost Dekkers, Frank van der Leeuw, and Jeroen van de Weijer, 151–189. Amherst: GLSA.

McCarthy, John J. 2003. OT constraints are categorical. Phonology 20 (1): 75–138.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1994. The emergence of the unmarked: Optimality in prosodic morphology. Ms., University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Rutgers University.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In Papers in Optimality Theory. Vol. 18 of University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers, eds. Jill N. Beckman, Suzanne Urbanczyk, and Laura Walsh Dickey, 248–383. Amherst: GLSA.

Meinschaefer, Judit. 2014. Right-alignment and catalexis in Spanish word stress. Ms., Freie Universität Berlin.

Molinu, Lucia. 2012. Le strutture non marcate negli ipocoristici del sardo. In Sardinian Network Meeting, University of Konstanz.

Molinu, Lucia. 2015. Gli ipocoristici dei nomi di persona in sardo. L’Italia Dialettale, Rivista di Dialettologia Italiana 73: 73–90.

Núñez Cedeño, Rafael, Sonia Colina, and Travis G. Bradley. 2014. Fonología generativa contemporánea de la lengua española. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Piñeros, Carlos-Eduardo. 2000a. Foot-sensitive word minimization in Spanish. Probus 12 (2): 291–324.

Piñeros, Carlos-Eduardo. 2000b. Prosodic and segmental unmarkedness in Spanish truncation. Linguistics 38 (1): 63–98.

Piñeros, Carlos-Eduardo. 2016. The phonological weight of Spanish syllables. In The syllable and stress: Studies in honor of James W. Harris, ed. Rafel A. Núñez Cedeño, 271–314. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Prieto, Pilar. 1992. Truncation processes in Spanish. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 22: 143–158.

Prince, Alan. 1980. A metrical theory for Estonian quantity. Linguistic Inquiry 11 (3): 511–562.

Roca, Iggy. 1988. Theoretical implications of Spanish word stress. Linguistic Inquiry 19 (3): 393–423.

Roca, Iggy, and Elena Felíu. 2003a. Morphology and phonology in Spanish word truncation. In Topics in morphology: Selected papers from the third Mediterranean morphology meeting, eds. Geert Booij, Janet DeCesaris, Angela Ralli, and Sergio Scalise, 311–329. Barcelona: IULA, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Roca, Iggy, and Elena Felíu. 2003b. Morphology in truncation: the role of the Spanish desinence. In Yearbook of morphology 2002, eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 187–243. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sanz Álvarez, Javier. 2015. The phonology and morphology of Spanish hypocoristics. MA diss., University of Tromsø–Arctic Universtity of Norway.

Sanz Álvarez, Javier. 2017. A stratal analysis of truncation in Spanish: Morphological and phonological evidence. In Conference of the Student Organization of Linguistics in Europe (ConSOLE) 25. Leiden: Universiteit Leiden.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1980. The role of prosodic categories in English word stress. Linguistic Inquiry 11 (3): 563–605.

Soglasnova, Svetlana. 2003. Russian hypocoristic formation: A quantitative approach. PhD diss., University of Chicago.

Tesar, Bruce, and Paul Smolensky. 2000. Learnability in Optimality Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Topintzi, Nina. 2003. Prosodic patterns and the minimal word in the domain of Greek truncated nicknames. In International Conference of Greek Linguistics (ICGL) 6, 1–14.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Javier Sanz Álvarez, who kindly pointed us towards interesting data on trisyllabic truncated forms in Spanish and read a first draft of this paper. We also want to thank Michael Kenstowicz, the associate editor of this paper, and three anonymous reviewers for their time and helpful comments. Violeta Martínez-Paricio’s research was financially supported by the postdoctoral grant FJCI-2015-24202, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness and the University of València. Additionally, her research is part of the project FFI2016-76245-C3-3-P funded by AEI (Agencia Estatal de Investigación) and FEDER (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional). Likewise, Francesc Torres-Tamarit’s research is part of the project FFI2016-76245-C3-1-P funded by AEI (Agencia Estatal de Investigación) and FEDER (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional). Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Data

Appendix: Data

-

(39)

-

(40)

-

(41)

Trisyllabic nominal truncation (Felíu 2001:885)

a.nál.fa

←

a.nal.fa.bé.to

‘illiterate’

an.fé.ta

←

an.fe.ta.mí.na

‘amphetamine’

ca.má.ra

←

ca.ma.ré.ro

‘waiter’

ma.ní.fa

←

ma.ni.fes.ta.ción

‘demonstration’

te.lé.co(s)

←

te.le.co.mu.ni.ca.ció.nes

‘telecommunication studies’

co.lé.gui

←

co.le.guí.lla

‘colleague-dim’

in.dé.pe

←

in.de.pen.den.tís.ta

‘supporter of Catalan independence’

-

(42)

The last two names in (42a), Etxéba and Beláuste, are Basque source names, but the truncated forms are used in Spanish. The TF Margári derives from the Spanish SF Margaríta but its use is restricted to the Spanish of the Basque Country.

-

(43)

Possible BTF derived from the SF in (42)

Tó.lo

←

Bar.tó.lo

Én.car

←

En.car.na.ción

Mé.re

←

E.me.ren.ciá.na

Már.ga

←

Mar.ga.rí.ta

Rí.ta

←

Mar.ga.rí.ta

Cá.ti

←

Ca.ta.lí.na

Lí.na

←

Ca.ta.lí.na

És.pe

←

Es.pe.rán.za

Fí.na

←

Jo.se.fí.na

Í.sa

←

I.sa.bél

Bé.la

←

I.sa.bél

Ní.co

←

Ni.co.lás

Ló.lo

←

Ma.nó.lo

←

Ma.nuél

Ís.ma

←

Is.ma.él

-

(44)

TTF derived from compound SF

Jo.sé.lu

←

Jo.se.luís

←

Jo.sé + Luís

Jo.sé.ma

←

Jo.se.ma.rí.a

←

Jo.sé + Ma.rí.a

Jo.sé.rra

←

Jo.se.ra.món

←

Jo.sé + Ra.món

Juan.dá.vi

←

Juan.da.víd

←

Juán + Da.víd

Juan.má.ri

←

Juan.ma.rí.a

←

Juán + Ma.rí.a

Luis.mí.gue

←

Luis.mi.gél

←

Luís + Miguél

Ma.riá.je

←

Ma.ria.je.sús

←

Ma.rí.a + Je.sús

Ma.riá.jo

←

Ma.ria.jo.sé

←

Ma.rí.a + Jo.sé

Ma.riá.te

←

Ma.ria.te.ré.sa

←

Ma.rí.a + Te.ré.sa

Mi.gué.lan

←

Mi.gue.lán.gel

←

Mi.guél + Án.gel

Te.ré.lu

←

Te.re.sa.lóur.des

←

Te.ré.sa + Lóur.des

-

(45)

BTF from compound SF

Juán.ma

←

Juan.ma.rí.a

←

Juán + Ma.rí.a

Juán.ra

←

Juan.ra.món

←

Juán + Ra.món

Juá.nan

←

Jua.nan.tó.nio

←

Juán + An.tó.nio

Luís.ma

←

Luis.ma.rí.a

←

Luís + Ma.rí.a

Luís.mi

←

Luis.mi.gél

←

Luís + Miguél

-

(46)

-

(47)

Truncated toponyms

San.tá.co

←

Santa Colóma (city in Catalonia)

Cas.té.fa

←

Castelldeféls (city in Catalonia)

Ma.ssál.fa

←

Massalfassár (town in Valencia)

-

(48)

Kinship appositional phrase

Ta.tá.lo

←

Tata Lóla

‘aunt Lola’

Cristina Real Puigdollers (p.c.)

-

(49)

Truncated phrases in the Spanish slang of youngsters

me.ló.fo

←

me lo follaría

‘I would have sex with him’

Sanz Álvarez (p.c.)

me.lá.fo

←

me la follaría

‘I would have sex with her’

Sanz Álvarez (p.c.)

por.sí.fo

←

por si follo

‘In case I have sex’

yu.ná.mer

←

y una mierda

‘no way’

me.cá.güen

←

me cago en diez

‘goddammit’

por.siá.ca

←

por si acaso

‘just in case’

Sanz Álvarez (2017)

la.qué.li

←

la que limpia

‘cleaning lady’

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Paricio, V., Torres-Tamarit, F. Trisyllabic hypocoristics in Spanish and layered feet. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 659–691 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9413-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9413-4