Abstract

We tested whether a self-support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs to increase students’ basic need satisfaction, mindfulness, and subjective vitality, and decrease their need frustration, coronavirus, and test anxiety during the novel coronavirus and university final exams. Three hundred and thirty students (Mage = 21.45, SD = 2.66) participated in this 6-day long experimental study and they were randomly allocated to either experimental (self-support approach, n = 176) or control (no-intervention) condition. Students completed the targeted questionnaires at the beginning (first day of the university final exams, Time 1) middle (3 days after the beginning of the study, Time 2), and the end of study (6 days after the beginning of the study, Time 3). Compared to students in the control condition, students in the experimental condition reported higher need satisfaction, mindfulness, subjective vitality, and lower need frustration, coronavirus, and test anxiety. Through a path analysis, the experimental condition predicted positively students higher need satisfaction, which in turn, predicted their higher subjective vitality, and lower coronavirus and test anxiety at Time 3. Results highlighted the importance of a self-support approach on students’ outcomes during difficult situations, that have implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 1985b; Ryan & Deci, 2017), all human beings have three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, that their satisfaction are essential nutrients for greater well-being and performance. Empirical and intervention research has found that basic psychological need satisfaction resulted in intrinsic motivation, development, optimal performance, and well-being (e.g., Cheon et al., 2018, 2020). The satisfaction of basic psychological needs most likely happens when social agents (e.g., teachers) support these basic needs (Behzadnia et al., 2018; Haerens et al., 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2020). However, the spread of novel coronavirus has created a stressful situation that social agents like teachers were not ready or available to provide support for their students (Behzadnia et al., 2021). Similar to this stressful situation, in some other situations social agents would not be available or their role to help students are less than expected, such as university final exams that students experience higher stress (Zunhammer et al., 2013). Such stresses would most likely arise when students feel two stressors simultaneously, exam stress during the coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, students may feel deprivation or frustration with their basic needs in these situations. In this experimental study, we employed the SDT principles to create and test an explanatory and easy-to-implement self-support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs during stressful situations—that is, in a lack of social agents support how students can rely on inner recourses to satisfy their basic needs, and better cope with stressors and experience greater well-being.

Basic psychological needs

SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985b; Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020) is a macro-theory of human motivation and wellness with strong implications for different domains, such as education, health, work, and sport. Within SDT, the need for autonomy refers to the experience of choice and willingness, the need for competence refers to the experience of effectiveness in doing things, and the need for relatedness refers to positive and meaningful relationships with others. SDT describes that basic psychological needs are universal regardless of age, gender, socio-demographical status, cultural background, personality, and situations (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

When social agents (e.g., parents or teachers’ interpersonal behaviors) are supportive of these basic needs, individuals experience need satisfaction, whereas, when social agents are not supportive or thwarting of needs, it results in experiencing need frustration (Behzadnia, 2021; Rocchi et al., 2017). That is, for example, when students feel that they are authors of their behaviors and decisions, experience self-endorsement and authenticity, and choose how to do things, their need for autonomy is satisfied; when students feel that they are competent in doing things, and feeling success in the activities, their need for competence is satisfied; and when students feel that they are belonging to a group or society, and feel warmth and closeness in interacting with friends, their need for relatedness is satisfied. In contrast, the frustration of basic needs are most likely to occur, for example, when students feel that they have no choice or they are forced to do many things and feel a chain of obligation in their activities (autonomy frustration); when students feel disappointed and fail with their performance, and feel incompetent in their abilities (competence frustration); and when students feel that their surrounding people are cold and distance toward them, and feel excluded from groups (relatedness frustration) (Chen et al., 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Research has shown that need satisfactions were related to positive outcomes such as higher performance, persistence at activities, and greater well-being, whereas, need frustrations were related to less engagement at the activities, depression, and poor performance (Behzadnia et al., 2018; Ntoumanis et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020).

Social and hierarchical relationships to satisfy basic psychological needs

Previous intervention studies in SDT showed that different social environments played important roles in determining individuals’ basic needs. Below, we briefly describe interventions at the societal and hierarchical levels (Table 1). Extending this framework, we then propose the intervention at the individual level (a self-support approach).

Teachers

SDT-based interventions in educational domains have shown proximal influences on students’ positive outcomes, such as engagement, learning, and well-being (Cheon et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2020) For example, Cheon et al. (2012) showed that when teachers acknowledged and accepted students’ negative affects, and provided explanatory rationales, students experience greater need satisfaction, and demonstrated higher intention to continue activities. A recent meta-analysis by Vasconcellos et al. (2020) also showed that teachers’ need-supportive behaviors helped students to enhance their intrinsic motivation as well as resulted in higher engagement in activities and greater well-being. Thus, when teachers’ interpersonal behaviors are supportive of students’ basic needs, students enhance their autonomous motivation, and experience greater well-being and prosocial behaviors, and lower ill-being (Cheon et al., 2018; Su & Reeve, 2011).

Parents

Parents’ need-supportive behaviors were associated with children’s experience of need satisfaction and positive outcomes. For example, research has shown that parents using behavioral limitation strategies were accentuated in need-supportive climates. That is, logical consequences as a behavioral limitation strategy to limiting children’s behavior that require them to take responsibility for their actions would accentuate when parents support children’s basic needs (Mageau et al., 2018). Research has also shown that parents’ need-supportive behaviors (e.g., providing children with positive and informational feedback and encouraging interesting challenges) were related to children’s favorable motivational outcomes and experience of need satisfaction (Mabbe et al., 2018).

Managers

Work organizations have benefited from need-supportive styles (Deci et al., 2017). Research showed that when managers adopted a need-supportive motivating style toward employees, the employees showed higher intrinsic motivation and greater work engagement (Hardré & Reeve, 2009). For example, to support workers’ basic needs, managers focused on nurturing workers’ inner motivational resources, and provided an explanatory rationale for requests (Hardré & Reeve, 2009; Jungert et al., 2021). Recent meta-analyses and review research has also confirmed that need-supportive behaviors at the workplace were effective in increasing workers’ intrinsic motivation, performance, and job-related behaviors (Cerasoli et al., 2016; Slemp et al., 2021; Van den Broeck et al., 2016).

Coaches

An abundant research in sport and physical activity domains has shown that supporting athletes’ basic needs resulted in greater well-being and performance (e.g., Bhavsar et al., 2020). Coaches’ need-supportive behaviors (e.g., provide meaningful choice and rationale with specific rules, take athletes’ perspective into account, and facilitate athletes’ self-improvement focus) fostered athletes’ need satisfaction as well as related to anti-doping intention and goal achievement (Berntsen & Kristiansen, 2019; Bhavsar et al., 2019; Ntoumanis et al., 2021). In contrast, coaches’ less supportive or need-thwarting behaviors were related to athletes’ experience of need frustration and higher ill-being (Bhavsar et al., 2019).

Health instructors

Another important environment that has received important attention is the health domain, where either health instructors (e.g., physicians or coaches) or clients benefited from need-supportive climates (Ng et al., 2012; Teixeira et al., 2020). It has shown that instructors’ need-supportive behaviors helped clients to pursue healthy behaviors, as well as experienced greater need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and well-being (Ntoumanis et al., 2020). For example, in need-supportive climates, the instructor provides clients (or patients) with options and choices, take their perspectives and avoid ego-involvement, and reduce controlling behaviors and pressures them to behave in prescribed ways (Behzadnia, Kiani, et al., 2020; Halvari et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2009). In addition, need-supportive climates have been found to help clients to actively involve them in treatment programs and evidenced in greater maintained healthy behaviors (Williams et al., 1996).

Peers

Interesting research has also shown that colleagues’ (e.g., co-workers or peers) need-supportive behaviors were related to positive outcomes. Team members, for example, by expressing their viewpoints and listening actively to each other, and trying to see how each member views him or herself and how to view the other members, would increase each other’s need satisfaction and autonomous motivation, and decrease controlled motivation (Jungert et al., 2018). Moreover, it has shown that peers who created need-supportive environments can play an important role in others’ experience of need satisfaction and positive outcomes (Chu & Zhang, 2019).

Hierarchical level

Generally, it has been proposed that need-supportive behaviors across different sources in the organizational hierarchies would relate to employees’ behaviors (Slemp et al., 2018). That is, the distance between supervisor–employees (ranging from proximal to distal sources) may relate to employees’ motivation and basic needs. State differently, when social contexts are available or close to individuals, it may result in greater need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and well-being.

Above we briefly discussed findings regarding the effect of social contexts in supporting individuals’ basic needs. SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017) mostly emphasized the role of social contexts in determining individuals’ basic needs and related outcomes. In the current study, rather than societal and hierarchical levels, we aimed to examine how intervention at the individual level would affect individuals’ need satisfaction—that is, how individuals can rely on inner resources to fulfill their basic needs. It means that we proposed that all people can regulate their behaviors to get their basic needs satisfied regardless of their hierarchies levels.

Self-Support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs

Awareness

Research has shown that when individuals’ basic needs are fulfilled during stressful situations like the final exams (Campbell et al., 2018) and the novel coronavirus pandemic (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020; Cantarero et al., 2020), they experience greater well-being and lower stress. However, despite the crucial role of social agents in satisfying (vs. frustrating) basic needs, social agents sometimes are not available to create need-supportive environments (or even behave indifferently or thwart these basic needs) during stressful situations. So, it might that the absence of social agents leads to the experience of need frustration. Need frustration would increase psychological distress during stressful situations, but, when persons can do some activities to meet their need satisfaction, they can buffer against psychological distress. That is, if one learns and understands the nature of basic needs, it would help him or her to create situations to experience need satisfaction. One can engage proactively in the activities to fulfill needs without waiting for social agents to create situations to fulfill their basic needs (Ryan et al., 2019), but an insightful understanding of basic needs and clear perceptions about them would help individuals to find ways to satisfy them (Deci et al., 2015). To effectively create situations, one requires some level of interest or awareness (Deci & Ryan, 1985b). When individuals are aware of what is occurring, they experience autonomy and engage in more authentic behaviors, whereas, under pressure, one’s awareness tends to be low as he or she needs to focus on external contingencies rather than the true self (Deci et al., 2015). To be aware, it is important to find interest in the activities—that is, when individuals know about the nature of basic needs and why they are important, they may find them interesting and look for ways to satisfy them. Finding interest in the activities not only results in putting more effort to find solutions, but also results in enhancing the experience of need satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 1985b; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Although this is not so easy, if individuals recognize their capacity, they can get their basic needs satisfied. In the current study, we aimed to help students to understand how to create such situations and recognize their capacities to do so.

According to SDT, all individuals have a natural tendency toward growth and development, yet, this is conditional and it requires social support to satisfy basic needs (Deci & Ryan, 1985b, 1987). To satisfy needs, SDT recognizes the role of an inherent capacity for awareness that relates to being aware of one’s goals and needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This capacity for awareness would support autonomous actions (Ryan et al., 2021). Autonomous actions or intrinsic motivation imply that persons feel that their behaviors are truly chosen by themselves, rather than by external controls (de Charms, 1968; Deci, 1975). That requires to take interest in inner and outer events that engage one’s curiosity as well as seeing objects without manipulations, resistance, and judgments (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Deci et al., 2015). When individuals take an open interest and are fully aware of their emotions and experiences, they act volitionally and responses are congruent with their values (Weinstein & Ryan, 2011). So, it is possible that when a person is aware of his or her needs can more actively choose what he or she needs, and look inside of his or her system to be the author of his or her actions.

Being self-supportive required some level of awareness—that is, for example, one can take responsibility for his actions if he is aware of his feelings or experiences. So, we expect that awareness would be the main step toward becoming self-support. In other words, taking an open interest in creating situations to be self-support would result in greater need satisfaction and positive related outcomes. While it is not so simple, anyone can create a supportive environment to satisfy basic needs if they learn and actively engage in the programs (Jungert et al., 2018). With awareness about basic needs, one can be more autonomous and authentic in doing things that would help the person to integrate new challenges and constraints that were initially external to the self (Deci & Flaste, 1995). That is, persons can be volitional and free even when they are under pressure or have to behave in certain ways if their acts are fully endorsed by the self (Ryan et al., 2021). In other words, one can comply with external circumstances with an authentic evaluation because he or she willingly obeys those circumstances and values those inputs (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Therefore, when individuals can aware of their basic needs, they can create situations to fulfill their basic needs by themselves with a full sense of autonomy and authenticity.

Needs-as-motives

Besides the importance of awareness to satisfy basic needs, theoretically, a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs, would somewhat relate to, the definition of needs-as-motive (Sheldon & Schüler, 2011). In this view, when people see their needs as motives or formulate them as goals to satisfy specific needs, this arouses their implicit motives and thus, motivates them toward the activities (Prentice et al., 2014). That is, needs as motives is simply that needs not only represent satisfactions but also represent goals or aims to which people gravitate. Therefore, the satisfaction of psychological needs is not always depend on the effects of social agents, further, when individuals learn about the nature of their basic needs, they would motivate toward satisfying them and activate their behaviors to satisfy them as well as would result in greater well-being (Prentice et al., 2014). In the current study, our aim is to make the value of basic needs salient in awareness and explicit as goals to see if they lead to enhanced wellness. Implicit goals were not a focus of measurement or manipulation—rather the idea is an explicit intervention to make needs also motives.

Creating situations to experience need satisfaction would result in intrinsically motivated toward daily activities as well as experience greater vitality and less amotivation (lack of any motivation) and stress during stressful situations (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020). Whenever a person feels the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, he or she regulates behaviors intrinsically, pursue goal-directed behaviors, and experience well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017). That is, in the activities that persons can feel the satisfaction of basic needs, they can experience well-being (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020; Deci & Flaste, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Weinstein et al., 2016). Thus, in the absence of social agents, one can still thrive and create situations to get his or her basic needs satisfied.

In the current study we aimed to teach students (I) why basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness are important for their goal-directed behaviors, performance, and well-being, (II) what does each basic need means, (III) and how they can fulfill their basic needs and rely on their inner resources or being self-orientated in supporting themselves to feel the satisfaction of these basic needs. In other words, individuals can help themselves by thinking about how to get their needs satisfied. That is, persons can think about what to do to get their needs satisfied if they know what does basic needs mean and why they are important for their psychological well-being and performance. For example, to get autonomy satisfaction, one can take responsibility for himself or herself; to get competence satisfaction, one can focus on learning how to do things that think are important to himself or herself; and to get relatedness satisfaction, one can develop relationships with others. When a person learns and knows how to be responsible for his or her needs, he or she can figure out how to get needs satisfied and nurture a self-supporting system in satisfying basic needs.

The present study

There is little, to the best of our knowledge, to specifically investigate how persons can support their basic psychological needs. It is important to create interventions to be freely available for all people when they do not have access to their social agents to receive support. From a self-affirmation theory, individuals can boost adaptive functioning and experience well-being under difficult situations when they gain confidence in their abilities and develop relationships with others (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Howell, 2017). When individuals can see themselves as adequate and good persons, they can value the important aspects of the self to experience higher self-integrity (Easterbrook et al., 2021). In other words, a more expansive view of the self by given choice would enhance positive functioning over time (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). In addition, research has also shown that enhancing awareness or mindfulness would help individuals to clearly describe their need satisfaction—that is, learning about mindfulness positively change the perception about psychological need satisfaction (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2018). Therefore, individuals can find a way to feel more need satisfaction and support their basic needs when they learn and are aware of their basic needs (Deci et al., 2015). To do this, the interventions that aim to help individuals to re-find themselves and learn about their basic psychological needs, without costs or access to specific things, would be helpful for all people in order to experience greater need satisfaction and increase positive functioning.

Four outcome variables of mindfulness, subjective vitality, test anxiety, and the novel coronavirus anxiety were examined. Mindfulness is a highly important factor for individuals to live a meaningful life as it is a necessary ingredient of self-regulation and it is an important way to make a variety of choices that are congruent with the self (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Deci et al., 2015). Being mindful helps individuals to better select goals and activities, and to have open attention to the events that also engage their curiosity, as well as protect individuals from stressors and foster well-being (Deci et al., 2015; Schultz & Ryan, 2019). Subjective vitality reflects on eudaimonic or psychological well-being and fully functioning which refers to having energy and feeling alive (Ryan & Deci, 2008; Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Previous research has shown that subjective vitality is an important outcome that results from the experience of need satisfaction (e.g., Martela & Ryan, 2016; Vergara-Torres et al., 2020). Moreover, research showed that higher levels of subjective vitality moderate the effect of coronavirus anxiety on maladaptive feelings (Arslan et al., 2020). Generally, when basic needs are satisfied, persons can more mindfully do their activities and experience greater vitality (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The satisfaction of basic psychological has also related negatively to anxiety during final exams (Goodman et al.; Maralani et al., 2016)—that is, the satisfaction of basic needs would result in decreasing anxiety (Yu et al., 2016). In addition, the current stressful situation of the novel coronavirus has led to psychological distress such as anxiety (Brooks et al., 2020; Lee, 2020a, 2020b), so we also aimed to test how a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs would modify and reduce the negative effects of coronavirus and test anxiety.

Based on the SDT, one important function of need satisfaction is to enhance vitality and reduce anxiety, contrary, when needs satisfaction are not experienced or basic needs are frustrated, higher anxiety to threat will experience (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2017). Need satisfaction also is a contributor of mindfulness, and the more one can receive basic need support (from social agents), the more he or she can be mindful, and thus, experience greater well-being and lower ill-being (Brown et al., 2007; Goodman et al., 2021). Therefore, these positive (mindfulness and subjective vitality) and negative (test and coronavirus anxiety) outcomes variables would depict how a self-supportive approach act in different ways during difficult times.

In this study, we also measured students’ physical activity behaviors as a control variable. Higher physical activity behaviors were related positively to the experience of need satisfaction and well-being, and negatively to need frustration and ill-being (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2007; Standage & Ryan, 2012). Previous research, generally, has also shown that physical activity was related to need satisfaction and well-being during difficult times (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020). It might that those people who pursue a healthy lifestyle (physical activity behaviors) tend to be more self-support or self-orientated toward their basic psychological needs, though they may not know what exactly each basic needs mean. Thus, in the current study, we control physical activity behaviors when examining the effectiveness of the self-support intervention on the study variables.

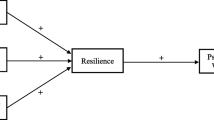

To test a self-support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs on outcome variables, we tested an easy-to-implement intervention to teach and encourage students to think and create situations to support and satisfy their basic needs during the difficult times of final exams and the coronavirus pandemic. The intervention offers a framework in which students can understand what each basic psychological needs mean, why they are important, and how they can get their basic needs satisfied. That is, we aimed to teach students to find ways, re-discover, and support themselves to get their basic needs satisfied, as well as to increase their mindfulness and vitality and reduce their anxiety. To do this, we provided the intervention and asked students to do one activity each day to support their basic needs to increase the satisfaction of basic needs, each day one of the basic needs and longs for 6 days (Table 2). We, therefore, hypothesized that students in the experimental condition (self-support of basic psychological needs), would increase their experience of need satisfaction, mindfulness, and subjective vitality more than students in the control condition (no-intervention) (Hypothesis 1) during the university final exams and the coronavirus pandemic. We also hypothesized that students in the experimental condition would decrease their experience of need frustration, coronavirus anxiety, and text anxiety more than students in the control condition (Hypothesis 2). We also tested an SDT-based theoretical process model of well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017) to examine the effects of the self-support intervention on the targeted psychological needs (i.e., need satisfaction and frustration) and related outcomes (i.e., mindfulness, vitality, coronavirus, and test anxiety). Specifically, we tested a model to examine whether a self-support approach would predict changes in need satisfaction and need frustration and, in turn, affect outcomes at the end of the study (Time 3). Thus, we hypothesized that self-support intervention would positively predict need satisfaction and, in turn, predict mindfulness and subjective vitality at Time 3 (Hypothesis 3). We also hypothesized that the intervention would predict negatively need frustration and, in turn, predict coronavirus and test anxiety at Time 3 (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants and procedures

The study sample comprised 330 university students (female = 233 females) in the age range of 18 to 38 years (Mage = 21.45, SD = 2.66), that most of them were single (89.39%), and they took online courses for the first time due to the coronavirus pandemic in North-Western Iran. One week before the beginning of online university exams, we contacted six teachers to ask their students to attend the study, and then informed them that the study aims to examine their psychological states during final exams and the novel coronavirus in general. Students who agreed to attend the study were randomly allocated to either experimental (self-support of basic psychological needs, n = 176) or control (no-intervention, n = 154) conditions. That is, we firstly allocated teachers into the conditions. We asked students in each group to not share what they were asked to do with students from another group, though most of the students were junior (94.55%), and we choose students from different departments (physical education, mathematics, engineering, science, psychology, and geography). After that, we created two groups in the WhatsApp mobile application, one group for students in the experimental condition and one group for students in the control condition.

The consent form was obtained from all students who participated in this study. We assured all participants about the anonymity and confidentiality of the study processes. The University Ethical Board approved the study protocol. The inclusion criterion was being the student, and the exclusion criteria involved students who have a history of a psychological illness recognized by a psychologist or a psychiatrist such as psychotic disorders or depression.

Students completed the study questionnaires that was created for them in the Google Docs and provided for them through WhatsApp groups in three waves, the beginning of the study (Time 1), middle of the study (3 days after the beginning of the study, Time 2), and the end of the study (3 days after the middle of the study, Time 3) (see Fig. 1). In the Google Docs link, we noted that all questions are required to be answered, but if they did not interest in answering them, they still could participate in the program. Due to the problems in internet connection and submitting the questionnaire, we required all questions to answer because when we checked submitted questionnaires at Time 1, we found that some of them submitted without answering questions while they reported that they answered all the questions. So, there were no missing values. At Time 1, students (N = 330) completed all questionnaires employed in the study (basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration, mindfulness, subjective vitality, test anxiety, coronavirus anxiety, physical activity behaviors, and demographic questions). At Time 2, 309 students completed the questionnaires (subjective vitality, test anxiety, and coronavirus anxiety), while 21 students did not. The Time 2 dropout students scored lower on Time 1 need satisfaction, but they did not differ in need frustration, mindfulness, subjective vitality, test anxiety, coronavirus anxiety, and physical activity behaviors. At Time 3, 286 students completed all questionnaires (basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration, mindfulness, subjective vitality, test anxiety, and coronavirus anxiety) while 23 of the Time 2 remaining students did not. The Time 3 dropout students did score lower at Time 1 need satisfaction but did not differ on need frustration, mindfulness, subjective vitality, test anxiety, coronavirus anxiety, and physical activity from remaining students in the experimental condition. In addition, the Time 3 dropout students did score higher at Time 2 coronavirus anxiety but did not differ from the remaining students in the experimental condition at Time 2 subjective vitality and test anxiety (see Appendix 1 for comparing between dropout and persistent participants on the study variables). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 286 students (female = 72.73%) at Time 3, of those 153 students were in the experimental group.

Self-support of basic psychological needs intervention

Based on SDT (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Weinstein et al., 2016), a six-day program was provided for students in the experimental condition (self-support of basic psychological needs) at the beginning of the first week of the final university exams (Table 2). The instruction included three sections: first, why basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are important for their goal-directed behaviors and well-being; second, what does each of the basic psychological needs means, either the satisfaction or the frustration of needs; and third, how to create conditions that could help them to feel the satisfaction of basic needs each day (one day for each of the basic needs). We asked students to try to do activities to satisfy all of their basic needs—that is, we suggested to do activities to feel autonomy satisfaction on Saturday and Tuesday, do activities to feel competence satisfaction on Sunday and Wednesday, and do activities to feel relatedness satisfaction on Monday and Thursday. In addition, we told students that they can do the activities based on their preferences—that is, for example, one can do activities to feel competence satisfaction on Saturday, and do activities to feel autonomy satisfaction on Sunday. They were asked to follow the instruction and read that each day. At the same time, as a part of the intervention program, we asked them to create conditions that minimize frustration or dissatisfaction with their basic needs. In this regard, research assistance (RA) reminded students to do the activities and she was available to answer questions regarding the program. Students in the control condition were asked to fill out the questionnaire three times as did the students in the experimental condition.

Measures

Demographic information

We collected some demographic information to better assess the effectiveness of the intervention on variables employed in this study, including age, gender, marital status, level of education, and socioeconomic status (SES). Students’ SES was assessed using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective status (Adler et al., 2000). Participants selected a staircase from 1 (Lowest level) to 10 (Highest level), related to their economic status, income, and amenities, based on the number of stairs.

Experience of basic psychological needs

Students’ basic psychological needs were assessed through the 12-item shortened version (Behzadnia et al., 2018) of the Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Need Frustration Questionnaire (BPNSNFQ; Chen et al., 2015). The satisfaction of basic needs was assessed with 6 items, of which two items tapped into each basic need. Sample items included “I feel that my decisions reflect what I really want” (autonomy satisfaction), “I felt competent to achieve my goals” (competence satisfaction), and “I feel close and connected with other people who are important to me” (relatedness satisfaction). The frustration of basic needs was assessed with 6 items, of which two items tapped into each basic needs. Sample items included: “I feel forced to do many things I wouldn’t choose to do” (autonomy frustration), “I feel disappointed with many of my performance” (competence frustration), and “I have the impression that people I spend time with dislike me” (relatedness frustration). The stem of this scale was “During my daily activities …”. Students responded on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 7 (Completely true). In the current study, we measure the composite of need satisfaction and need frustration by averaging the sum of the three needs. Previous research has reported the internal structure of the BPNSNFQ among Iranian samples (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020).

Mindfulness

Students’ mindfulness was assessed through the five-item version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003). The sample item included “I find myself doing things without paying attention”. Students were asked, “Please indicate how frequently or infrequently you currently have experience the following …?”. Students responded on a scale ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 7 (Almost always). In the current study, we measured the internal structure of the MAAS through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The CFA yielded a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 = (3) 9.59; p = 0.14; RMSEA = 0.08; RMSEA 95% CI = 0.03 to 0.14; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.03. The factor loadings of all items were above 0.51, p < 0.001.

Subjective vitality

Students’ subjective vitality was assessed through the five-item version of the Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS; Ryan & Frederick, 1997). The sample item included “I have energy and spirit”. Students were asked, “To what degree do you typically feel each of the following …?”. Students responded on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 7 (Very much true). The shortened version of the SVS has been used in Iranian samples (Behzadnia & Ryan, 2018).

Coronavirus anxiety

To measure students’ coronavirus anxiety, we used the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (Lee, 2020a). Students were asked, “How often have you experienced the following activities over the last days?”. The scale included five items (e.g., “I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus”). Students responded on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Almost every day). The results of CFA to assess the internal structure of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale, yielded a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 = (4) 7.85; p = 0.37; RMSEA = 0.05; RMSEA 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.11; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.02. The factor loadings of all items were above 0.47, p < 0.001.

Perceived test anxiety

To assess students’ test anxiety, we used the Tenseness subscale of the Perceived Test Anxiety Scale (Friedman & Bendas-Jacob, 1997). The Tenseness subscale was measured with six items, sample item included “I am very tense before a test, even if I am well prepared”. Because of the online exams during the coronavirus, we modified items and the stem of the scale to better assess online exams, by adding the stem “How do you feel about the test during online exams?”. Students rated each statement on a scale ranging from 1 (Do not characterize me at all) to 5 (Characterizes me most perfectly). The results of CFA yielded a good fit to the data, χ2 = (9) 12.15; p = 0.7 RMSEA = 0.03; RMSEA 95% CI = 0.00 to 0.075; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.03. The factor loadings of all items were above 0.52, p < 0.001.

Physical activity behaviors

To assess students’ physical activity behaviors, we used a two-question tool of the Physical Activity Behaviors (Marshall et al., 2005). Questions deal with “How many times a week, do you usually do 20 min of vigorous physical activity that makes you sweat or puff and pant?” and “How many times a week, do you usually do 30 min of moderate physical activity or walking that increases your heart rate or makes you breath harder than normal?”. Sufficiently physical activity behaviors scored ≥ 4, and insufficient behaviors scored 0–3.

Data analysis

The normality of the data was examined through indices of kurtosis and skewness (Kline, 2015). After removing two cases with outliers (in students’ coronavirus anxiety), the absolute values of kurtosis indices ranged from − 1.03 to 6.32, and the absolute values of skewness indices ranged from − 0.97 to 2.45. These indices were less than 8 (for kurtosis) and 3 (for skewness), and based on Kline’s (2015) recommendation these values are not severely non-normally distributed.

We then assessed the effects of self-support of basic needs intervention on students’ need satisfaction and need frustration, mindfulness, subjective vitality, perceived test anxiety, and coronavirus anxiety. To assess the effects of self-support intervention on students’ need satisfaction and need frustration, and mindfulness, we conducted 2 (experimental and control conditions) × 2 (time of assessment) repeated measures ANCOVAs (covariates included: gender, SES, and physical activity behaviors), one for need satisfaction, one for need frustration, and one for mindfulness. To assess the effects of self-support intervention on students’ subjective vitality, perceived test anxiety, and coronavirus anxiety, we conducted 2 (experimental and control conditions) × 3 (time of assessment) repeated measures ANCOVAs, one for subjective vitality, and one for perceived test anxiety, and one for coronavirus anxiety.

In the follow-up multiple comparisons, we employed Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure that is more powerful than the traditional (or standard) Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979) in preventing the inflation of Type I error and multiple testing problems. In addition, before testing the hypotheses, we computed power analysis for two conditions (experimental and control) repeated measures analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2; Faul et al., 2014). With power = 0.95, p = 0.05, and expected medium effect size of d = 0.40 (Cohen’s d) among a set of six variables (plus three covariates), power determined the total sample size of 151 is needed. The sample size at Time 1 was N = 330, thus, we determined that we had sufficient participants to test our hypotheses.

To test the hypothesized model, we stipulated direct paths between the condition at Time 1 and need satisfaction and need frustration at Time 3. We also assumed direct associations between need satisfaction and need frustration at Time 3 with mindfulness, vitality, coronavirus anxiety, and test anxiety at Time 3. For need satisfaction, need frustration, mindfulness, vitality, coronavirus anxiety, and test anxiety at Time 3, a direct path is also stipulated from their corresponding baseline (Time 1) score (e.g., Time 1 need satisfaction has a direct path to Time 3 need satisfaction). Moreover, for vitality, coronavirus anxiety, and test anxiety at Time 3, a direct path is stipulated from their corresponding score at Time 2 (e.g., Time 2 vitality has a direct path to Time 3 vitality), as well as for these variables at Time 2, a direct path is stipulated from their corresponding score at Time 1 (e.g., Time 1 vitality has a direct path to Time 2 vitality). Path analysis with full information maximum likelihood in conjunction with bootstrapping (bootstrap samples = 5000), was employed to test the hypothesized model (H3, and H4) in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Indirect effects were examined using bootstrap bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Table 3 shows students’ demographic information. Preliminary analyses showed that physical activity behaviors and SES were related to most of the study variables (see Table 4), but age was not related to the study variables. Next, through MANOVA we examined mean differences in students’ gender, marital status (single and married), and education level (undergraduate and master). Compared to male students, we found that female students reported higher test anxiety at Time 2, F = (1, 284) 17.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, and Time 3, F = (1, 284) 4.76, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.02. For all other variables, differences between male and female students were insignificant. Because of the unequal sample size on students’ gender, we checked analyses through Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances. There were no differences between students’ marital status and education level. Therefore, we only included gender, physical activity behaviors, and SES as covariates in the analyses.

Manipulation check (need satisfaction and need frustration; Hypothesis 1, 2)

The intervention fidelity was assessed in two ways. First, students reported their experience of need satisfaction and need frustration results from the intervention at Time 1 and Time 3. Second, students were asked to complete two questions regarding the intervention at Time 2 and Time 3, which included (1) “Have you done the activities on previous days?” (short answer “Yes” or “No”), (2) “Have you found that the activities were useful for you?” (range from 1 Not useful, to 5 Useful). Generally, students reported that they have done the activities 100% at Time 2, and 99% at Time 3, and they found this program 74.20% at Time 2, and 83.62% at Time 3 useful for them.

For students’ experience of need satisfaction, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 31.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, and the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 17.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, were significant, but the main effect for time was not significant, F (1, 281) = 2.56, p = 0.11, ηp2 = 0.01. As Fig. 2(a) shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition increased from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.54, 95% CI [0.31, 0.54]), whereas it remained unchanged in the control condition (p = 0.07, d = 0.14, 95% CI [0.34, − 0.01]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.43, d = 0.09, 95% CI [0.31, − 0.13]), but students in the experimental condition reported higher need satisfaction than students in the control condition at Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.69, 95% CI [0.51, 1.01]).

For students’ experience of need frustration, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 21.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07, the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 14.41, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05, and the main effect for time, F (1, 281) = 3.87, p = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.01, were significant. As Fig. 2(b) shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition decreased from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.49, 95% CI [− 0.63, − 0.33]), whereas it remained unchanged in the control condition (p = 0.29, d = 0.02, 95% CI [0.09, − 0.29]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.10, d = 0.18, 95% CI [0.04, − 0.49]), but students in the experimental condition reported lower need frustration than students in the control condition at Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.62, 95% CI [− 1.05, − 0.49]).

Positive outcomes: mindfulness and subjective vitality (Hypothesis 1)

For students’ mindfulness, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 10.81, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, was significant, but the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 3.29, p = 0.071, ηp2 = 0.01, and the main effect for time were not significant, F (1, 281) = 0.02, p = 0.89, ηp2 = 0.00. As Fig. 2(c) shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition increased from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.48, 95% CI [0.40, 0.77]), whereas it remained unchanged in the control condition (p = 0.78, d = 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.34, 0.25]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.89, d = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.31, 0.27]), but students in the experimental condition reported higher mindfulness than students in the control condition at Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.40, 95% CI [0.22, 0.81]).

For students’ subjective vitality, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 15.36, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05, and the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 11.79, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, were significant, but the main effect for time was not significant, F (1, 281) = 1.13, p = 0.32, ηp2 = 0.00. As Fig. 2(d) shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition increased from Time 1 to Time 2 (p < 0.001, d = 0.29, 95% CI [0.12, 0.50]), from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.39, 0.83]), and from Time 2 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.30, 95% CI [0.13, 0.47]), whereas it remained unchanged in the control condition from Time 1 to Time 2 (p = 0.85, d = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.18, 0.46]), from Time 1 to Time 3 (p = 0.20, d = 0.11, 95% CI [− 0.07, 0.41]), and from Time 2 to Time 3 (p = 1.00, d = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.29, 0.35]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.91, d = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.29, 0.26]), but students in the experimental condition reported higher subjective vitality than students in the control condition at Time 2 (p = 0.002, d = 0.34, 95% CI [0.15, 0.70]), and Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.63, 95% CI [0.51, 1.10]).

Negative outcomes: coronavirus and test anxiety (Hypothesis 2)

For students’ coronavirus anxiety, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 4.44, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.02, and the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 15.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05, were significant, but the main effect for time was not significant, F (1, 281) = 0.19, p = 0.82, ηp2 = 0.00. As Fig. 2e shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 (p = 0.006, d = 0.24, 95% CI [− 0.16, − 0.02]), from Time 2 to Time 3 (p = 0.025, d = 0.20, 95% CI [− 0.12, − 0.01]), and from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.44, 95% CI [− 0.23, − 0.07]), whereas it remained unchanged in the control condition from Time 1 to Time 2 (p = 1.00, d = 0.11, 95% CI [0.09, − 0.17]), from Time 1 to Time 3 (p = 1.00, d = 0.00, 95% CI [0.11, − 0.09]), and from Time 2 to Time 3 (p = 0.82, d = 0.09, 95% CI [0.16, − 0.06]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.26, d = 0.13, 95% CI [0.05, − 0.16]), but students in the experimental condition reported lower coronavirus anxiety than students in the control condition at Time 2 (p < 0.001, d = 0.44, 95% CI [− 0.32, − 0.10]), and at Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.53, 95% CI [− 0.33, − 0.13]).

For students’ test anxiety, the interaction effect of time × condition, F (1, 281) = 15.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05, and the main effect for condition, F (1, 281) = 4.15, p = 0.043, ηp2 = 0.02, were significant, but the main effect for time was not significant, F (1, 281) = 0.38, p = 0.67, ηp2 = 0.00. As Fig. 2(f) shows, simple main effect of time for the experimental condition decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 (p < 0.001, d = 0.39, 95% CI [− 0.58, − 0.28]), from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.81, 95% CI [− 1.00, − 0.66]), and from Time 2 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.43, 95% CI [− 0.57, − 0.24]), whereas simple main effect of time for the control condition decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 (p = 0.014, d = 0.26, 95% CI [− 0.53, − 0.05]), and from Time 1 to Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.21, 95% CI [− 0.42, − 0.11]), but it remained unchanged from Time 2 to Time 3 (p = 1.00, d = 0.05, 95% CI [0.23, − 0.28]). The two conditions did not differ at Time 1 (p = 0.90, d = 0.01, 95% CI [0.25, − 0.22]) and Time 2 (p = 0.40, d = 0.10, 95% CI [0.13, − 0.34]), but students in the experimental condition reported lower test anxiety than students in the control condition at Time 3 (p < 0.001, d = 0.56, 95% CI [− 0.78, − 0.33]).

Path analysis (Hypothesis 3, 4)

We firstly tested a model without control variables. However, the results did not demonstrate a good fit to data, χ2 = (76) 448.57; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.12; RMSEA 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.13; CFI = 0.80. After adding control variables, the hypothesized model demonstrated a good fit to the data χ2 = (67) 200.11; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; RMSEA 95% CI = 0.07 to 0.09; CFI = 0.93. The results showed that the self-support intervention was associated with higher need satisfaction and lower need frustration at the end of the program (Time 3), after controlling for baseline (Time 1) values of these variables. In turn, need satisfaction at Time 3 significantly positively predicted subjective vitality at Time 3, and negatively predicted coronavirus anxiety and test anxiety at Time 3. In addition, need frustration at Time 3 significantly positively predicted coronavirus anxiety and test anxiety at Time 3, and negatively predicted mindfulness and subjective vitality at Time 3 (Fig. 3).

The results of indirect effects demonstrated that the intervention positively predicted subjective vitality at Time 3 (β = 0.18 [95% CI 0.13 to 0.23]) via promoting need satisfaction at Time 3. We also found that the intervention negatively predicted coronavirus anxiety (β = − 0.08 [95% CI − 0.13 to − 0.05]) and test anxiety (β = − 0.05 [95% CI − 0.09 to − 0.03]) at Time 3 via promoting need satisfaction at Time 3. In addition, we found that the intervention positively predicted mindfulness (β = − 0.07 [95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.04]) and negatively predicted test anxiety (β = − 0.15 [95% CI − 0.10 to − 0.21]) at Time 3 via decreasing need frustration at Time 3.

Discussion

Research has demonstrated the importance of supporting basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness by social agents (e.g., teachers and parents) in students’ positive outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2017). However, there are some situations that either providers (e.g., teachers) or receivers (e.g., students) cannot receive support for their psychological needs. Specifically, the novel coronavirus outbreak pandemic created such restricted situations (Brooks et al., 2020). To reduce students’ psychological distress and help them to experience well-being during the pandemic and university final exams, according to the SDT guidance (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Weinstein et al., 2016), we investigated an easy-to-implement intervention to able students support their basic psychological needs by themselves. Findings, generally, supported our hypotheses in which a self-support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs helped students to experience greater need satisfaction, mindfulness, and subjective vitality as well as decreased need frustration, and help them to better cope with coronavirus and final test anxiety.

In this experimental research, we found that a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs positively increased students’ need satisfaction and decreased need frustration. Based on SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020) basic needs are important ingredients of individuals’ goal-directed behaviors and well-being. Previous research, generally, has also reported the importance of need satisfaction on positive outcomes during difficult times of the novel coronavirus (e.g., Cantarero et al., 2020; Šakan et al., 2020). Although social contexts would play an important role in individuals’ basic needs, in this study we found that students’ self-supportive approach would also play a significant role to satisfy basic needs, which may even consider more important than social agents’ effects during times of crisis. We thus conclude that self-support intervention is an effective approach to satisfy basic needs and reduce need frustration. When individuals learn how to support their basic needs by themselves, they can adopt this approach in their daily life, and it results in positive consequences.

One very intriguing contribution of this study is that the self-support approach affected students’ mindfulness. Mindfulness help to be fully aware of what is going on inside and outside oneself because it can enhance a sense of choice that is congruent with the self (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Deci et al., 2015), and vice versa, in this study we found that enhancing basic psychological needs would contribute to higher mindfulness. That is, while a self-support approach affected students’ mindfulness, this mindful processing would also help students to more likely make integrated self-functioning as they made choices in their activities (Ryan et al., 2021). In other words, when students tried to support their basic needs to be satisfied, it actually helped them to be more aware of their feelings as well as see openly and non-judgmentally events around themselves. Thus, it might that enhanced mindfulness contributes to the function of a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs, rather than an important result from the self-support approach. Mindfulness can conduce to well-being because it can help persons to less suffer from stressors and enhance their tendency to better cope with stressors (Weinstein et al., 2009). In addition, in this study, we found that the self-support approach affects mindfulness via decreasing need frustration. It means that the self-supportive approach helped students to decrease their need frustration, and that decrease in need frustration helped them to be more mindful.

Of interest, we also found that the self-support approach increased subjective vitality and decreased both coronavirus and test anxiety. The interpretation is that subjective vitality can be considered either as an outcome or as a predictor of outcomes related to health and behavioral sciences (Ryan & Deci, 2008). That is, it might that either increasing subjective vitality played as a mechanism of the self-support approach to decrease coronavirus and test anxiety, or vice versa, decreasing coronavirus and test anxiety played as a mechanism of the self-support approach to increase subjective vitality. This is also shown in the correlation table (Table 4), subjective vitality related negatively to test anxiety but not to coronavirus anxiety at Time 1, but after receiving the intervention, subjective vitality was associated negatively with both coronavirus and test anxiety at Time 2, and more strongly associated with both coronavirus and test anxiety at Time 3.

We also investigated a path analysis including the experimental and control conditions and variables at all three-time points, to test the mediating roles of need satisfaction and need frustration in the relations between the condition and outcome variables. The results, generally, supported our expectations that the self-supportive approach contributes to the study outcomes through the dual mechanism of basic needs, need satisfaction and need frustration. Regarding the bright side of basic needs, by increasing need satisfaction, a self-supportive approach affected subjective vitality (positively), and coronavirus and test anxiety (negatively). Regarding the dark side of basic needs, by decreasing need frustration, a self-supportive approach affected students’ mindfulness (positively), and test anxiety (negatively). However, our expectation regarding the mediating role of need satisfaction in the relationship between the self-support approach and mindfulness was not supported. Need satisfaction was positively associated with mindfulness at both Time 1 and Time 3 (see Table 4), but to see such mediation role, perhaps we need to test this relationship in the longer interventions. Extending the literature on SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017), generally, we found that a self-support approach contributes to students’ positive and negative outcomes during difficult times because it changed students’ experiences of need satisfaction and need frustration, respectively.

Importantly, the mechanisms underlying the self-support of each need are based on the basic psychological needs. That means, all humans have a set of basic psychological needs, and when individuals behave in ways to satisfy basic needs, it results in positive consequences (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Basically, recognizing one’s capacity to behave in ways that facilitate satisfaction of basic needs is an important mechanism underlying a self-support approach—that is to be aware of and behave in ways that satisfy basic needs. When people behave in ways that satisfy their basic needs, they experience positive outcomes and it helps them to engage in activities. In this study, we found that by setting activities to help people learn what does basic psychological needs mean and how to create situations to help them find ways to satisfy their basic needs, they could recognize their capacity to behave in ways that facilitate satisfaction of their basic needs. The important point is that when people do not have access to available resources to support their basic needs (e.g., teachers), they can still fulfill their basic needs if they recognize their capacity to behave in ways that provide them satisfaction. In other words, for example, when teachers are not available to create supportive environments, students can create situations for themselves by recognizing their capacity to get their basic needs satisfied. These findings extend the SDT propositions, that not only social contexts in the hierarchical levels can create and support individuals’ basic needs, but also, in the absence of social contexts, in an individual level, persons can still support their basic needs and experience greater need satisfaction.

One other important finding of this study is that when people can see their needs as motives and formulate them as goals, it results in greater need satisfaction and positive outcomes. That is, making the value of basic needs salient in awareness and explicit as goals helped students to experience greater need satisfaction, mindfulness, and vitality, as well as decreased their need frustration, and both test and coronavirus anxiety. Importantly, it is possible that when individuals made the value of basic needs in this way, it helped them to gain confidence in their abilities and see themselves as adequate (Cohen & Sherman, 2014) and important/good individuals, so that they experience higher self-integrity (Easterbrook et al., 2021). In this way, people can become more flexible, and when they adapted to a flexible system, they can set goals and regulate their behaviors in difficult situations (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). Moreover, being aware of basic needs might help students to clearly understand and describe their basic needs (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2018), and this understanding of needs would help them to regulate their behaviors more adaptively and experienced positive outcomes.

In addition, in this study, we examined the effect of a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs and enhance mindfulness and vitality and reduce anxiety among university students. Although all people need to experience need satisfaction regardless of their age or gender (e.g., Behzadnia, Deci, et al., 2020), university students face important challenges in their lives especially during the pandemic, for example, to gain expertise and find a job in the future. Moreover, some students experienced more challenges at the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak as they had problems in terms of internet connection or access to devices (e.g., smart phone or computer) in order to connect to their university people and attend their online courses. They might feel higher stress because of the pandemic or because of their problems in their work. Therefore, in this study, the university students were considered as potential samples to test a self-support approach, but to better examine the universality and effectiveness of this approach, future research needs to replicate these findings with other samples, such as school students, employees, athletes, and older people, or among different cultures (e.g., North America).

Practical implications and study limitation

In the current study, we found that this easy-to-implement intervention affected students’ basic needs and their outcomes. Teachers, for example, can use this intervention and introduce these basic needs to students, either during difficult times such as final exams or even from the beginning of the semester. At the same time, by defining some activities to satisfy students’ basic needs (Behzadnia & FatahModares, 2020) and introducing this self-supportive approach in their classes, students may benefit more from both activities and the self-support approach together. Of course, many people would not know about the concept of basic needs, that the satisfaction of them is essential for their goal-directed behaviors and well-being, but they have done the activities that have felt good in the past when they were doing them—thus, they can put more importance on them after they learned about these concepts. One important result that we found is that the self-supportive approach affected students’ mindfulness—therefore, when students can see their environments mindfully, they can even moderate the negative effects of social environments to get their positive outcomes (Deci et al., 2015; Schultz et al., 2015). Thus, by learning this approach they can learn better how to be the author of their life and determine the best within themselves.

One of the limitations of the current study is that we investigated students in a geographical place, and we must be cautious to generalize the findings to other places because it might that students’ experiences of basic needs or their outcomes affected by different social environments and therefore, affect their perspectives toward a self-supportive approach to satisfy their basic needs. Another limitation was the time of the intervention, a six-day intervention. We aimed to no longer than 6 days ask students to do the activities and fill out the questionnaires because of their limitations during final exams, so future research needs to test this approach in longer terms to see how possibly students benefit from this approach. We look forward to doing such research. It would be also interesting to examine this self-support from a developmental approach, for example, how parents or teachers affect students’ perspectives to support themselves (or they see students’ basic needs indifferently, or act in a thwarting way toward them). Moreover, the important mechanisms of self-supportive style may be in part related to students’ personality or their motivational causality orientations (Deci & Ryan, 1985a) so future research needs to test these as well. We can, however, generalize the findings of this study to a broader population as findings showed that age was not related to the study variables.

Another limitation of the current intervention is that to be able to do a self-support approach to satisfy basic needs might require some level of energy, some set of abilities, self-regulation, and specific cognitions. While these need further research, we tested this approach among university students that they generally have some set of abilities (e.g., self-study, seeking knowledge, or problem-solving abilities as they learn) that may help them to better recognize their capacities to support their basic needs. As discussed in the introduction, different social environments can affect the satisfaction of basic needs, but to better understand how different social environments can benefit from a self-support approach and which abilities they need to do this, future research is thus needed.

This study, create various new research direction that, for example, how persons could help themselves in the absence of social agents to follow their goal-directed behaviors in stressful situations; where self-supportive approach come from, inner resources or it gradually develop and it just needs to teach and aware persons about these needs; and how self-supportive approach independently from social agents’ roles affect the experience of basic psychological needs and positive outcomes, or how they may interact with each other. It would be also interesting to examine the effectiveness of this approach in free or non-stressful situations, normal daily life, perhaps after the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, it would be interesting to examine how this approach affects motivational regulations (e.g., intrinsic and extrinsic motivations).

In addition, this study is among the first of its kind, and as such the results need replication and intervention need further exploration. Some important questions emerged in this study, for example, how many activities do participants need to do to feel greater need satisfaction and less need frustration? Through a daily diary study, it would be interesting to see in which places during a day (e.g., university, gym, or at home) one can create a self-support climate and how this climate affects their basic needs and goal-directed behaviors. It is also important to examine whether the findings are a consequence of the self-support activities themselves or simply that participants have become more aware of their needs in general? To examine this, future research can create a self-support scale and awareness about basic needs (or the importance of basic needs), and examine both self-support and awareness scales in relation to affective outcomes during each day—so that they can examine which variable would predict better outcomes, or how their interaction relate to affective outcomes. All of these questions would show interesting findings.

Conclusion

Our intent in this study was to test an easy-to-implement self-support approach to satisfy basic needs during difficult situations. Findings, generally, supported our expectations. When students learned how to create a climate to get their basic needs satisfied, they experienced higher need satisfaction and lower need frustration, which in fact, they experienced higher mindfulness and subjective vitality, and lower coronavirus and test anxiety. As we move further into the pandemic, students may see additional uncertainties and difficulties, therefore, a self-support approach to satisfy basic psychological needs may consider as a promising approach to deal with such difficulties and save their energy to continue their goal-directed behaviors.

Change history

28 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09984-9

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., & Aytaç, M. (2020). Subjective vitality and loneliness explain how coronavirus anxiety increases rumination among college students. Death Studies, 46(5), 1042–1051.

Behzadnia, B., Deci, E. L., & DeHaan, C. R. (2020a). Predicting relations among life goals, physical activity, health, and well-being in elderly adults: a self-determination theory perspective on healthy aging. In Self-Determination Theory and Healthy Aging (pp. 47–71). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6968-5_4

Behzadnia, B. (2021). The relations between students’ causality orientations and teachers’ interpersonal behaviors with students’ basic need satisfaction and frustration, intention to physical activity, and well-being. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(6), 613–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1849085

Behzadnia, B., Adachi, P. J. C., Deci, E. L., & Mohammadzadeh, H. (2018). Associations between students’ perceptions of physical education teachers’ interpersonal styles and students’ wellness, knowledge, performance, and intentions to persist at physical activity: A self-determination theory approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 39, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.07.003

Behzadnia, B., Alizadeh, E., Haerens, L., & Aghdasi, M. T. (2021). Changes in students’ goal pursuits and motivational regulations toward healthy behaviors during the pandemic: A Self-Determination Theory perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102131

Behzadnia, B., & FatahModares, S. (2020). Basic psychological need-satisfying activities during the COVID-19 outbreak. Applied Psychology: Health and Well Being, 12(4), 1115–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12228

Behzadnia, B., Kiani, A., & Babaei, S. (2020b). Autonomy-supportive exercise behaviors promote breast cancer survivors’ well-being. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(4), 409. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2020.60

Behzadnia, B., Rezaei, F., & Salehi, M. (2022). A need-supportive teaching approach among students with intellectual disability in physical education. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 60, 102156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102156

Behzadnia, B., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Eudaimonic and hedonic orientations in physical education and their relations with motivation and wellness. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 49, 363–385. https://doi.org/10.7352/IJSP.2018.49.363

Berntsen, H., & Kristiansen, E. (2019). Guidelines for need-supportive coach development: The Motivation Activation Program in Sports (MAPS). International Sport Coaching Journal, 6(1), 88–97.

Bhavsar, N., Bartholomew, K. J., Quested, E., Gucciardi, D. F., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Reeve, J., Sarrazin, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2020). Measuring psychological need states in sport: Theoretical considerations and a new measure. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 47, 101617.

Bhavsar, N., Ntoumanis, N., Quested, E., Gucciardi, D. F., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Ryan, R. M., Reeve, J., Sarrazin, P., & Bartholomew, K. J. (2019). Conceptualizing and testing a new tripartite measure of coach interpersonal behaviors. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 44, 107–120.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237.

Campbell, R., Soenens, B., Beyers, W., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2018). University students’ sleep during an exam period: The role of basic psychological needs and stress. Motivation and Emotion, 42(5), 671–681.

Cantarero, K., van Tilburg, W. A., & Smoktunowicz, E. (2020). Affirming basic psychological needs promotes mental well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620942708

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Nassrelgrgawi, A. S. (2016). Performance, incentives, and needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness: A meta-analysis. Motivation and Emotion, 40(6), 781–813.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Lee, J., & Lee, Y. (2015). Giving and receiving autonomy support in a high-stakes sport context: A field-based experiment during the 2012 London Paralympic Games. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 19, 59–69.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Lee, Y., Ntoumanis, N., Gillet, N., Kim, B. R., & Song, Y.-G. (2019). Expanding autonomy psychological need states from two (satisfaction, frustration) to three (dissatisfaction): A classroom-based intervention study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(4), 685. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000306

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Moon, I. S. (2012). Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 34(3), 365–396.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Ntoumanis, N. (2018). A needs-supportive intervention to help PE teachers enhance students’ prosocial behavior and diminish antisocial behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 74–88.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2020). When teachers learn how to provide classroom structure in an autonomy-supportive way: Benefits to teachers and their students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 90, 103004.

Chu, T. L., & Zhang, T. (2019). The roles of coaches, peers, and parents in athletes’ basic psychological needs: A mixed-studies review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(4), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119858458

Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371.

de Charms, R. (1968). Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behavior. Academic Press.

Deci, E. L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 580.

Deci, E. L., & Flaste, R. (1995). Why we do what we do: Understanding self-motivation. Penguins Books.

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985a). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985b). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1024

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Schultz, P. P., & Niemiec, C. P. (2015). Being aware and functioning fully. In K. W. Brown, R. M. Ryan, & J. D. Creswell (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 112–129). Guilford Press.

Easterbrook, M. J., Harris, P. R., & Sherman, D. K. (2021). Self-affirmation theory in educational contexts. Journal of Social Issues, 77(3), 683–701.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2014). G* Power Version 3.1. 9.2 [Computer Software]. Uiversität Kiel, Kiel.

Friedman, I. A., & Bendas-Jacob, O. (1997). Measuring perceived test anxiety in adolescents: A self-report scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 1035–1046.

Froiland, J. M. (2011). Parental autonomy support and student learning goals: A preliminary examination of an intrinsic motivation intervention. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40, 135–149.

Goodman, R. J., Trapp, S. K., Park, E. S., & Davis, J. L. (2021). Opening minds by supporting needs: do autonomy and competence support facilitate mindfulness and academic performance? Social Psychology of Education, 24, 119–142.

Grolnick, W. S., Levitt, M. R., Caruso, A. J., & Lerner, R. E. (2021). Effectiveness of a brief preventive parenting intervention based in self-determination theory. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(4), 905–920.

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2015). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 26–36.

Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2007). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in exercise and sport. Human Kinetics.

Halvari, A. E. M., Halvari, H., Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Predicting dental attendance from dental hygienists’ autonomy support and patients’ autonomous motivation: A randomised clinical trial. Psychology & Health, 32(2), 127–144.

Hardré, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2009). Training corporate managers to adopt a more autonomy-supportive motivating style toward employees: An intervention study. International Journal of Training and Development, 13(3), 165–184.