Abstract

Procrastination is common among college students, involving irrational delay of task completion. Theorists understand procrastination to be an avoidance response to negative emotions. Past research suggests that depression and anxiety predict procrastination. However, only limited research has examined the unique effects of shame and guilt—self-conscious emotions—on procrastination, and no studies have examined potential mechanisms. Depressive rumination, the repetitive and maladaptive thinking about a negative event composed of brooding and reflective pondering, is uniquely predicted by shame—but not guilt—and also predicts greater procrastination. Thus, the current cross-sectional survey study examined (1) whether shame and guilt uniquely predict procrastination and (2) whether depressive rumination mediates those effects in a collegiate sample. Results supported a model wherein brooding and reflective pondering mediate the unique relationship between shame and procrastination. A second model suggested that guilt leads to less procrastination directly but greater procrastination indirectly via increased reflective pondering. Theoretical and clinical implications of the current findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

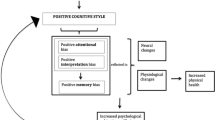

Procrastination is a pervasive issue with myriad negative consequences. Some 50% of college students procrastinate chronically (Steel, 2007). Procrastination is linked to poorer academic outcomes, depression, anxiety, and higher stress (Beswick et al., 1988; Flett et al., 2016). Because it is such a prevalent and problematic behavior, research on the predictors of procrastination tendencies has important treatment implications. Sirois and Pychyl (2013) proposed that procrastination is an avoidance response to experiencing negative affective states while engaging in or anticipating future unpleasant tasks. In previous research, depressed and anxious moods do in fact lead to procrastination and short-term emotion regulation efforts at the cost of completing necessary tasks (e.g., Baumeister et al., 2007; Constantin et al., 2018). Unlike the more basic emotions of sadness and anxiety, the self-conscious emotions reflect an evaluative process whereby people compare themselves to others or to a set of standards or goals. Because these emotions involve a distressing comparison of self with standards and/or other people, they seem particularly relevant for behaviors reflecting task performance, such as procrastination. In this study, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the self-conscious emotions of shame and guilt on procrastination, as mediated by depressive rumination. Studying the contribution of these specific negative emotions, as well as a potential mechanism, should guide future prevention and intervention efforts to decrease procrastination.

Shame and guilt—the two most commonly studied self-conscious emotions—occur when people have failed to meet perceived moral or social standards (Gausel & Leach, 2011; Tangney et al., 2007). Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) conceptualizations of these dysphoric emotions suggest that both emotions involve overestimation of one’s failing and unrealistic ideas about others’ disapproval (Dryden, 2013). Similarly, both shame and guilt can lead to self-defeating and self-punitive behaviors. Despite these similarities, REBT theorists and other researchers propose meaningful conceptual differences between these two self-conscious emotions.

Shame is a dysphoric feeling of contrite self-criticism (Gausel & Leach, 2011). It is associated with self-consciousness and feelings of inferiority and involves condemning the entire self, not just one’s failed action (Dryden, 2013; Watson & Clark, 1992). This condemnation of one’s entire identity reflects global and stable attributions of one’s own inadequacy, as well as assumptions of condemnation and rejection from others (Gausel & Leach, 2011; Shanahan et al., 2011; Tracy et al., 2007). Because shame involves perceived inferiority about one’s self-image and social-image, it is theorized to be more aversive than guilt, thereby contributing to more defensive behaviors and poorer psychological functioning (Tangney et al., 1996). In fact, shame is associated with increased withdrawal, behavioral avoidance, and depression (Fee & Tangney, 2000; Orth et al., 2006).

Guilt is also a dysphoric feeling, strongly associated with sadness (Watson & Clark, 1992). Cognitively, whereas shame reflects global concerns about self- and social-image, guilt involves judgment of a specific action as wrong, as well as attempts to understand why one made the moral failure and how to repair it (Dryden, 2013). Because the focus is on understanding the problem and how to fix it, guilt likely reflects concerns with social-image but not global self-image (Gausel & Leach, 2011). Accordingly, guilt is more likely to inspire corrective behavior to restore one’s social-image and mitigate the effects of harmful behavior. In support of this theory, guilt is related to greater perspective-taking, desire to make amends, and forgiveness-seeking behaviors (Joireman, 2004; Tangney et al., 1996).

Because shame is more aversive and more strongly associated with avoidance, we propose that shame but not guilt likely triggers procrastination. The limited research examining the effects of shame and guilt on procrastination supports this hypothesis. Two studies with university students found significant correlations between shame, but not guilt, and procrastination (Fee & Tangney, 2000; Martinčeková & Enright, 2018). Only the former of these two studies examined the unique effects of shame and guilt. Because shame and guilt are significantly intercorrelated, it is best to examine their unique effects in a single model (e.g., Orth et al., 2006). Therefore, one aim of the current study was to explore whether shame—but not guilt—uniquely predicted greater procrastination. A second aim was to examine whether rumination constitutes a mechanism of the effect of shame—but not guilt—on procrastination.

Rumination, or repetitive thinking about negative events and experiences, prolongs negative affect and predicts a wide range of negative clinical outcomes (e.g., Watkins, 2008). Because of its association with negative affect, researchers have theorized that rumination elicits avoidance coping responses like procrastination (Constantin et al., 2018). This theory has been studied specifically with depressive rumination, or the tendency to perseverate on the causes, experiences, and consequences of sad moods (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). For instance, depressive rumination was associated with greater procrastination in college students (Flett et al., 2016). In another study, depressive rumination mediated the effects of anxiety and depressive symptoms on procrastination (Constantin et al., 2018). Depressive rumination is often measured as consisting of two related constructs: brooding reflects passive comparison of one's current situation with some unachieved standard, whereas reflective pondering assesses analytic efforts to understand one’s depressed mood (Treynor et al., 2003). Brooding is consistently associated with worse depressive symptoms; by contrast, reflective pondering has mixed associations (e.g., Szasz, 2011). To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the effects of brooding and reflective pondering separately on procrastination.

Finally, there is evidence that shame, but not guilt, is uniquely associated with greater depressive rumination. For instance, dispositional shame is related to heightened depressive rumination, even after controlling for guilt (Cheung et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 2011). By contrast, the association between guilt and depressive rumination is much less clear. Zero-order correlations between these constructs range from negative to zero to positive (Cohen et al., 2011; Smart et al., 2016). However, in one study that controlled for shame, guilt was uniquely associated with less depressive rumination (Cohen et al., 2011). In sum, shame seems to be uniquely associated with more depressive rumination, whereas the effect of guilt on depressive rumination is ambiguous.

The current cross-sectional study examined (a) the unique effects of shame and guilt on procrastination in college students and (b) whether depressive rumination constitutes one mechanism by which shame is associated with greater procrastination. We expected that shame but not guilt would uniquely predict greater procrastination. In addition, although nonexperimental research cannot prove a causal mediational model, we expected to find correlations consistent with depressive rumination mediating the association between the unique effect of shame and procrastination. Given past research on depressive rumination, we expected that this mediation effect would emerge for brooding but not necessarily for reflective pondering.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of 235 undergraduate students (Mage = 19.49 years, SD = 1.38, range = 18–26; 83% female) recruited from a college in the Northeast. The sample was 63% White/Caucasian, 4% Black/African American, 9% Hispanic/Latina, 10% Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander, 6% South Asian/Indian, and 9% Other.

Online data collection took place after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited from the Psychology department, provided informed consent, and received course credit as compensation. Participants were required to be 18 years of age or older; there were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. The measures were part of a larger survey that took approximately 30 min to complete, and the order of all questionnaires and items was randomized. This study was approved by the College’s institutional review board and followed all ethical guidelines for research with human subjects.

Measures

Shame and Guilt

The Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA; Tangney et al., 2000) measures shame- and guilt-proneness in response to hypothetical life events. For each scenario, reactions are rated on a five-point scale from extremely unlikely to extremely likely. The shame items assess general self-condemnation (e.g., “You would think, ‘I’m inconsiderate’”) and desire to withdraw (e.g., “You would feel like you wanted to hide”). The guilt items assess emotional distress and intention for reparative behavior (e.g., “You would feel unhappy and eager to correct the situation”). We only scored the items assessing shame and guilt and created average total scores across 10 of the 11 total scenarios (one scenario was not applicable for college students). This measure has good construct validity (Woien et al., 2003). Internal consistency for shame and guilt in the current sample study were acceptable (α’s = 0.82 and 0.71, respectively).

Rumination

The 10-item Ruminative Responses Scale (Treynor et al., 2003) assesses tendencies for depressive rumination. Participants respond to all items on a 4-point scale from 1 (Almost never) to 4 (Almost always). Higher summed scores represent greater rumination. This scale has two subscales, brooding and reflective pondering. These subscales show good convergent and discriminant validity (Schoofs et al., 2010; Treynor et al., 2003). Internal consistency for brooding and reflective pondering subscales in this sample were acceptable (α’s = 0.73 and 0.80, respectively).

Procrastination

The 12-item Pure Procrastination Scale (Steel, 2010) is intended to measure facets of procrastination relating to decision-making, implementation, and timeliness or lateness. Participants respond to statements on a five-point scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Higher mean scores indicate higher procrastination tendencies. The measure has good construct validity (Steel, 2010) and demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.91).

Results

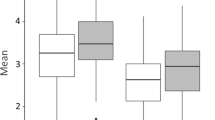

All variables were normally distributed except for guilt, which we successfully normalized using a square root transformation. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all study variables are in Table 1. Higher shame significantly correlated with greater guilt, brooding, reflective pondering, and procrastination. Guilt was not significantly correlated with brooding or procrastination, although it was associated with more reflective pondering. Finally, higher brooding and reflective pondering correlated with more procrastination. Females reported significantly higher shame and brooding, whereas males reported more guilt, all p’s < 0.05.

We used regression to first examine the unique effects of shame and guilt on procrastination. In this total effects model, shame uniquely predicted greater procrastination (β = 0.25, t = 3.64, p < 0.001), while guilt uniquely predicted less procrastination (β = − 0.18, t = − 2.53, p = 0.01). We then ran a mediational model with brooding mediating these two associations. We used the SPSS macro PROCESS to test the significance of mediation by calculating bootstrap estimates and bias-corrected confidence intervals for each indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). In the mediational model, shame significantly predicted more brooding (β = 0.22, t = 3.20, p = 0.002), whereas guilt did not (β = 0.06, t = 0.80, p = 0.43). Brooding significantly predicted greater procrastination (β = 0.15, t = 2.30, p = 0.02). The direct effects of both shame and guilt on procrastination remained significant (β = 0.22, t = 3.09, p = 0.002; β = − 0.17, t = − 2.44, p = 0.02; respectively). Finally, the indirect effect for shame was significantly different than 0 (IE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.0084 to 0.0934]). The indirect effect of guilt was not significant (IE = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.0648 to 0.2959]).

Next, we ran a second mediational model with reflective pondering as the mediator for the effects of shame and guilt on procrastination. Both shame and guilt significantly predicted greater reflective pondering, (β = 0.152, t = 2.20, p = 0.029; β = 0.148, t = 2.15, p = 0.033; respectively). Reflective pondering significantly predicted more procrastination (β = 0.24, t = 3.59, p < 0.001). The direct effects of both shame and guilt on procrastination remained significant (β = 0.22, t = 3.25, p = 0.001; β = − 0.20, t = − 2.92, p = 0.004; respectively). The indirect effect of shame on procrastination was significant (IE = 0.0418, 95% CI [0.0042 to 0.0987]). This time, the indirect effect of guilt was also significant (IE = 0.2795, 95% CI [0.0460 to 0.6686]). Because of the gender differences in several variables, we also reran all of our models controlling for gender; the results (not shown) were unchanged.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine whether depressive rumination mediates the unique effects of shame and guilt on procrastination. Using a cross-sectional survey of college students, we examined the unique effects of both shame and guilt on procrastination, as well as whether depressive rumination mediates the effects of shame and guilt and procrastination. We hypothesized that shame but not guilt would uniquely predict more procrastination. We also expected that the brooding subscale of depressive rumination would mediate the unique effect of shame on procrastination. The present study is the first to our knowledge to examine the unique and indirect effects of shame and guilt on procrastination via both brooding and reflective pondering. Different findings emerged for shame and guilt, and each is addressed in turn below.

In line with hypotheses, shame uniquely predicted greater procrastination. This finding aligns with the two previous studies to examine the effect of shame on procrastination (Fee & Tangney, 2000; Martinčeková & Enright, 2018). Our results build on past research by finding that depressive rumination is a potential mechanism of this association. Specifically, both brooding and reflective pondering mediated the unique effect of shame on procrastination. This pattern aligns with past findings that shame predicts greater depressive rumination (Cheung et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 2011). Shame elicits feelings of self-condemnation, global incompetence, and severe perceived defects in social- and self-image. This negative focus on self-identity may lead to rumination, as people are especially likely to ruminate when their core sense of self is challenged. Thus, rumination may be a particularly common cognitive response to shameful feelings that in turn increases task-avoidant behaviors such as procrastination. Interestingly, shame uniquely predicted both brooding and reflective pondering individually as separate sub-constructs, which to our knowledge has not been studied before. Although brooding is more consistently associated with depressive symptoms, both brooding and reflective pondering focus on general self-image as well as comparing oneself negatively to others. Given that shame reflects self-condemnation concerning one’s self- and social-image, it makes sense that shame increases both brooding and reflective pondering.

Our findings with guilt did not parallel those with shame. First, although guilt was not correlated with procrastination, in regression analyses it uniquely predicted less procrastination. In previous studies to examine guilt and procrastination, the associations were also negative, although non-significant (Fee & Tangney, 2000; Martinčeková & Enright, 2018). These results alone suggest that some unique aspect of guilt—perhaps its association with fixing problems—leads to less procrastination. Interestingly, guilt predicted greater reflective pondering but did not significantly predict brooding. Accordingly, reflective pondering but not brooding mediated the unique effect of guilt on procrastination. Specifically, guilt predicted greater reflective pondering, which in turn predicted greater procrastination. We can infer from this suppressor effect that guilt directly leads to less procrastination but also indirectly increases procrastination through greater repetitive thinking about reasons for one’s negative mood. Taken together, these results suggest that guilt, when separated from shame, influences procrastination in two distinct, contradictory ways. Future research will have to explore reasons for this suppressor effect. Arguing that guilt is a multidimensional construct, some researchers have assessed two components of guilt: fear of impending punishment and need for reparation (Caprara et al., 1992). Fear of punishment, but not need for reparation, is associated with greater rumination. The authors suggest that guilt may have maladaptive or functional outcomes based on whether it is fear-driven or empathy-driven. Thus, the two contradictory pathways between guilt and procrastination could reflect guilt being a more multifaceted construct than is usually assessed.

Limitations in this cross-sectional study can be addressed by future research. Longitudinal and/or experimental study designs would facilitate conclusions about directionality and causality, which is particularly important for a mediational model. Because there were so many women in this sample, it is unclear how well our results generalize to men. Women experience shame and depressive rumination more frequently than men (Kushnir et al., 2016; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Wetterlöv et al., 2021). Not surprisingly, women in our sample reported more shame and brooding than did men. Although none of the study results changed when controlling for gender, future research should include more men to be able to better generalize these results.

Other limitations include our choice of measures. First, the measure of shame and guilt we used is not fully reflective of the REBT conceptualization of these constructs. Specifically, the TOSCA (Tangney et al., 2000) assesses shame primarily as self-condemnation and inclination for withdrawal, and guilt primarily as desire for reparation. These operationalizations focus more on the cognitive aspects of shame and guilt, rather than their feeling states. Thus, the different associations we found between shame versus guilt and procrastination may reflect the impact of cognitive appraisals and behavioral tendencies, rather than dysphoric affects. In addition, we cannot tease apart the relative relevance of self-versus social-image that we discussed in our conceptualization of these constructs. Although the TOSCA has been widely used, future research should employ more nuanced measures of shame and guilt. Finally, although we measured depressive rumination because of the preponderance of previous studies doing the same, future researchers might develop a measure of rumination specifically about shame and guilt. Such a measure would more directly test the theory that shame and guilt lead to repetitive thinking about those emotions.

Procrastination makes a significant impact not only on individual mental and physical health, but on the economy as well. Spira and Feintuch (2005) concluded that $588 billion is lost in U.S workplace productivity each year due to distractions stemming from use of technology, (e.g., social media, email, internet surfing) that result in procrastination. Americans who wait until the day before Tax Day to file their taxes pay an additional $400 in unnecessary taxes due to rushing and missing eligible deductions (Kane, 2014). Addressing solutions for minimizing the impact of procrastination is critical. The present findings suggest that depressive rumination (both brooding and reflective pondering) mediates the unique effect of shame on procrastination. Guilt may also increase procrastination by promoting reflective pondering. Thus, any therapy that targets shame and in particular rumination should help prevent procrastination. One of the core founding components of REBT is shame-attacking exercises (Ellis, 1995). More recently, evidence shows that training in mindfulness decreases both shame and rumination (Goffnett et al., 2020; Proeve et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2008). In fact, integrating mindfulness with REBT leads to decreases in shame (Chenneville et al., 2017). In addition, rumination-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy effectively decreases rumination (Jacobs et al., 2016). Given these promising treatments, mental health providers have many options for using rumination- and shame-focused interventions in order to prevent procrastination.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Zell, A. L., & Tice, D. M. (2007). How emotions facilitate and impair self-regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 408–426). The Guilford Press.

Beswick, G., Rothblum, E. D., & Mann, L. (1988). Psychological antecedents of student procrastination. Australian Psychologist, 23(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050068808255605

Caprara, G. V., Manzi, J., & Perugini, M. (1992). Investigating guilt in relation to emotionality and aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90193-S

Chenneville, T., Machacek, M., Little, T., Aguilar, E., & De Nadai, A. (2017). Effects of a mindful rational living intervention on the experience of destructive emotions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 31(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.31.2.101

Cheung, M.S.-P., Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2004). An exploration of shame, social rank and rumination in relation to depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(5), 1143–1153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00206-X

Cohen, T. R., Wolf, S. T., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2011). Introducing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 947–966. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022641

Constantin, K., English, M. M., & Mazmanian, D. (2018). Anxiety, depression, and procrastination among students: Rumination plays a larger mediating role than worry. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0271-5

Dryden, W. (2013). Dealing with Emotional Problems Using Rational-Emotive Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. Routledge.

Ellis, A. (1995). Changing rational-emotive therapy (RET) to rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 13(2), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354453

Fee, R. L., & Tangney, J. P. (2000). Procrastination: A means of avoiding shame or guilt? Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 15(5), 167–184.

Flett, A. L., Haghbin, M., & Pychyl, T. A. (2016). Procrastination and depression from a cognitive perspective: An exploration of the associations among procrastinatory automatic thoughts, rumination, and mindfulness. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 34(3), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-016-0235-1

Gausel, N., & Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(4), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.803

Goffnett, J., Liechty, J. M., & Kidder, E. (2020). Interventions to reduce shame: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 30(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2020.03.001

Jacobs, R. H., Watkins, E. R., Peters, A. T., Feldhaus, C. G., Barba, A., Carbray, J., & Langenecker, S. A. (2016). Targeting ruminative thinking in adolescents at risk for depressive relapse: Rumination-focused cognitive behavior therapy in a pilot randomized controlled trial with resting state fMRI. PLoS ONE, 11(11), e0163952. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163952

Joireman, J. (2004). Empathy and the self-absorption paradox II: Self-rumination and self-reflection as mediators between shame, guilt, and empathy. Self and Identity, 3(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000038

Kane, L. (2014, August 8). Why procrastinators pay an extra $400 on their taxes. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/procrastinators-pay-an-extra-400-on-their-taxes-2014-4#:~:text=Why%20Procrastinators%20Pay%20An%20Extra%20%24400%20On%20Their%20Taxes&text=That's%20because%2C%20according%20to%20H%26R,average%20an%20extra%20%24400%20each.

Kushnir, V., Godinho, A., Hodgins, D. C., Hendershot, C. S., & Cunningham, J. A. (2016). Gender differences in self-conscious emotions and motivation to quit gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 969–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9574-6

Martinčeková, L., & Enright, R. D. (2018). The effects of self-forgiveness and shame-proneness on procrastination: Exploring the mediating role of affect. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9926-3

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

Orth, U., Berking, M., & Burkhardt, S. (2006). Self-conscious emotions and depression: Rumination explains why shame but not guilt is maladaptive. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(12), 1608–1619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206292958

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Proeve, M., Anton, R., & Kenny, M. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on shame, self-compassion and psychological distress in anxious and depressed patients: A pilot study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 91(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12170

Schoofs, H., Hermans, D., & Raes, F. (2010). Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-010-9182-9

Shanahan, S., Jones, J., & Thomas-Peter, B. (2011). Are you looking at me, or am I? Anger, aggression, shame and self-worth in violent individuals. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 29(2), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-009-0105-1

Shapiro, S. L., Oman, D., Thoresen, C. E., Plante, T. G., & Flinders, T. (2008). Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 840–862. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20491

Sirois, F., & Pychyl, T. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12011

Smart, L. M., Peters, J. R., & Baer, R. A. (2016). Development and validation of a measure of self-critical rumination. Assessment, 23(3), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115573300

Spira, B. J., & Feintuch, B. J. (2005, September). The cost of not paying attention: How interruptions impact knowledge worker productivity. Basex. https://lib.store.yahoo.net/lib/bsx/basexcostpayes.pdf

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

Steel, P. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality and Individual Differences, 48(8), 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025

Szasz, P. L. (2011). The role of irrational beliefs, brooding and reflective pondering in predicting distress. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 11(1), 43–55.

Tangney, J. P., Dearing, R. L., Wagner, P. E., & Gramzow, R. (2000). Test of Self-Conscious Affect–3 (TOSCA-3) [Database record]. APA PsycTests.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372.

Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (2007). Self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. Guilford Press.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1992). On traits and temperament: General and specific factors of emotional experience and their relation to the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 441–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00980.x

Wetterlöv, J., Andersson, G., Proczkowska, M., Cederquist, E., Rahimi, M., & Nilsson, D. (2021). Shame and guilt and its relation to direct and indirect experience of trauma in adolescence, a brief report. Journal of Family Violence, 36(7), 865–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00224-7

Woien, S., Ernst, H., Patock-Peckham, J., & Nagoshi, C. (2003). Validation of the TOSCA to measure shame and guilt. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00191-5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oflazian, J.S., Borders, A. Does Rumination Mediate the Unique Effects of Shame and Guilt on Procrastination?. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 41, 237–246 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-022-00466-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-022-00466-y