Abstract

Objectives

It is well established that defendants who plead guilty receive reduced sentences compared to the likely outcome if convicted at trial. Prominent theories of plea bargaining posit that the plea discount is determined by the strength of the evidence against the defendant. Research on this claim has produced mixed findings, however, and others have suggested that discounts may be influenced by extra-legal characteristics such as race, age, and sex. To date, there have been few attempts to directly compare the effects of these factors on plea discount estimates.

Methods

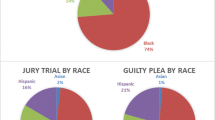

This study uses a penalized ridge regression to predict counterfactual trial sentences for a sample of defendants who pled guilty. Plea discounts are estimated using each defendant’s predicted trial sentence and observed plea sentence. Discount estimates are then regressed on variables related to case evidence and the demographic characteristics of the defendant.

Results

Results suggest that increases in the amount of evidence associated with a case lead to decreases in the size of the plea discount. Both main and interaction effects are observed for race/ethnicity and sex, with Hispanic and male defendants receiving significantly smaller discounts than White or female defendants. Calculation of standardized effect sizes further indicates that demographic characteristics exert larger effects on plea discount estimates than evidentiary variables.

Conclusions

Plea discounts appear to be influenced by both evidence and extra-legal factors. Legal participants may indeed consider the strength of the evidence when determining acceptable plea discounts, but this alone appears to be an insufficient explanation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While Ulmer et al. (2010) do not directly report this estimate, they do report a grand mean sentence of 62 months and suggest that the trial penalty would be approximately 28 months. This would correspond to a trial sentence of roughly 90 months and a plea discount of 31%. This discount decreased when Ulmer et al. controlled for various forms of guideline departures, though it remained statistically significant.

LaFree (1985) and Elder (1989) examined the impact of evidence on plea sentences but not plea discounts. While LaFree (1985) found physical evidence and number of witnesses to significantly increase plea sentences, confession evidence had no effect across all model specifications. Additionally, Elder (1989) found no significant effect of physical evidence, identification evidence, or confession evidence on plea sentence length. However, neither study directly examined the relationship between evidence and plea discounts.

It is also important to note that individual pieces of evidence can be of varying strength. For example, not all eyewitness evidence is equally strong; one witness may be a person with poor eyesight who witnessed the crime 100 yards away at night, whereas another witness may previously know the defendant and witnessed the crime up close and personal. To our knowledge, such indicators of the reliability of evidence are not available in archival datasets.

This two-year timeframe was chosen to match the data collection period for our target data set described below.

These data are available to download in bulk from https://virginiacourtdata.org/.

Two jurisdictions in Virginia do not make their case processing data publicly available. However, our data still represents over 98% of all jurisdictions in the state.

We acknowledge that this is an imperfect solution and that it is also possible for the severity and number of charges to be increased or decreased prior to trial. Given the parameters of our data, this approach provided the best adjustment for charge bargaining and is consistent with prior efforts of this kind (see Yan & Bushway 2018).

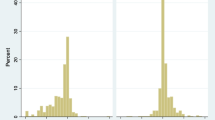

Only 214 (4%) of cases were censored at 600 across the full trial conviction sample. However, it is important to note here that we only included cases where a carceral sentence was imposed. While this approach improves the distribution of the outcome variable, it can create concerns regarding selection bias for any inferences aimed at the broader population of defendants (Bushway and Piehl, 2007; Elder 1989; Winship and Mare 1992). However, likely because we aggregated sentence lengths across all charges within a case, all cases in our trial conviction sample received some length of incarceration. Additionally, only 11% (n = 68) of eligible plea cases did not receive a carceral sentence. Thus, our estimation of trial sentences should not suffer from selection bias, though we note that our plea discount results are limited to defendants who pled guilty and received some term of incarceration.

More specifically, these factors would be explicitly modeled in both the dependent and independent variables, which may lead to correlations that are an “artifact of the model” (Bushway & Redlich 2012, p. 449). Because evidence and demographic factors are inherently included in the plea sentence but not in the trial sentence prediction, variation in the difference between these values may be attributed to these variables.

The inclusion of both a maximum potential sentence across all charges and a minimum potential sentence across all charges led to VIF values that were greater than 10 for these factors. To test the importance of including both variables, we ran an OLS regression including only the maximum potential sentence and its squared term and then added the minimum potential sentence and its squared term to the model. Results of an F-test indicated that the addition of these variables significantly improved model fit (F(2, 5635) = 365.02, p < 0.001).

We chose to use a ridge regression over similar methods such as the LASSO regression because, while the ridge regression shrinks parameters toward 0, it will never fully eliminate any coefficients from the model. In contrast, the penalty parameter in a LASSO regression is free to shrink coefficients to 0 and eliminate them from the model (Tibshirani 1996). While LASSO regressions may lead to more parsimonious models, we did not want any of our coefficients eliminated from the model, given that each variable has a theoretical connection to sentencing outcomes.

To do this we used the “glmnet.cv” function in the glmnet package (Hastie et al. 2016) in R statistical software. This function automatically generates a \(\lambda\) sequence between the minimum and maximum \(\lambda\) values.

For example, an OLS regression estimated using the non-logged dependent variable produced an R2 of 0.66 while the same model estimated with the logged dependent variable produced an R2 of 0.51. In this regard, it is important to reiterate that our dependent variable did not contain any 0 s and was top-coded, which reduced skew. Additionally, by including all charges associated with a case in cumulative fashion, our dependent variable may have better resembled an additive process.

Note that we also tested the number of pieces of evidence as a categorical variable using 0 pieces of evidence as the reference category. Results support the idea that this relationship resembled a linear one. Here, one piece of evidence decreased plea discounts by 28% (p = 0.05), two pieces of evidence decreased plea discounts by 29% (p = 0.04), three pieces of evidence decreased plea discounts by 42% (p < 0.01), and four pieces of evidence decreased plea discounts by 62% (p = 0.02), controlling for the presence of video/photo/audio evidence. However, operationalizing this measure as a categorical variable did not significantly improve model fit (F(2, 477) = 1.71, p = 0.18).

We had a limited sample with which to examine age. For example, 75% of White defendants, 75% of Black defendants, and 81% of Hispanic defendants were between the age of 18–39. Few defendants were in age groups where significantly decreasing punishment might be expected. Thus, our comparisons are predominately between young males in each racial category.

Note that only 12 Hispanic female defendants are represented in this sample, however.

The effect size for the number of pieces of evidence here represents a linear effect. If this effect size is calculated comparing defendants with four pieces of evidence to those with none, it becomes the largest effect (r = −.60, 95% CI [ −0.95, −0.26]). However, there are very few defendants with either zero or four pieces of evidence. A more realistic comparison of defendants with three pieces of evidence to those with one suggests an effect size of r = −0.15, 95% CI [ −0.27, −0.02], which remains smaller than both the interaction effect for being Hispanic and male, as well as the main effect for Hispanic alone.

References

Agresti A (2019) An introduction to categorical data analysis, 3rd edn. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ

Albonetti CA (1987) Prosecutorial discretion: the effects of uncertainty. Law Soc Rev. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053523

Albonetti CA (1990) Race and the probability of pleading guilty. J Quant Criminol 6(3):315–334

Alschuler AW (1968) The prosecutor’s role in plea bargaining. Univ Chicago Law Rev 36(1):50–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1598832

Alschuler AW (1981) The changing plea bargaining debate. Calif Law Rev 69:652

Bartlett JM, Zottoli TM (2021) The paradox of conviction probability: mock defendants want better deals as risk of conviction increases. Law Hum Behav 45(1):39

Bibas S (2004) Plea bargaining outside the shadow of trial. Harv Law Rev 117(8):2463–2547. https://doi.org/10.2307/4093404

Brereton D, Casper JD (1981) Does it pay to plead guilty? Differential sentencing and the functioning of criminal courts. Law Soc Rev 16(1):45–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053549

Bushway SD, Redlich AD (2012) Is plea bargaining in the “shadow of the trial” a mirage? J Quant Criminol 28(3):437–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9147-5

Bushway SD, Redlich AD, Norris RJ (2014) An explicit test of plea bargaining in the “shadow of the trial.” Criminology 52(4):723–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12054

Devine DJ, Buddenbaum J, Houp S, Studebaker N, Stolle DP (2009) Strength of evidence, extra evidentiary influence, and the liberation hypothesis: data from the field. Law Hum Behav 33(2):136–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-008-9144-x

Devine DJ, Clayton LD, Dunford BB, Seying R, Pryce J (2001) Jury decision making: 45 years of empirical research on deliberating groups. Psychol Public Policy Law 7(3):622

Dezember A, Luna S, Woestehoff SA, Stoltz M, Manley M, Quas JA, Redlich AD (2022) Plea validity in circuit court judicial colloquies in misdemeanor vs. felony charges. Psychol Crime Law 28:268–288

Edkins VA (2011) Defense attorney plea recommendations and client race: does zealous representation apply equally to all? Law Hum Behav 35(5):413–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-010-9254-0

Eisenberg T, Hannaford-Agor PL, Hans VP, Waters NL, Munsterman GT, Schwab SJ, Wells MT (2005) Judge-jury agreement in criminal cases: a partial replication of Kalven and Zeisel’s The American Jury. J Empir Leg Stud 2(1):171–207

Elder HW (1989) Trials and settlements in the criminal courts: an empirical analysis of dispositions and sentencing. J Leg Stud 18(1):191–208

Emmelman DS (1998) Gauging the strength of evidence prior to plea bargaining: the interpretive procedures of court-appointed defense attorneys. Law Soc Inq 22:927–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.1997.tb01093.x

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2016). Uniform crime report statistics, 2016. US Department of Justice.

Flowe HD, Mehta A, Ebbesen EB (2011) The role of eyewitness identification evidence in felony case dispositions. Psychol Public Policy Law 17(1):140

Fox J (2016) Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models, 3rd edn. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA

Frederick, B., and Stemen, D. (2012). The anatomy of discretion: An analysis of prosecutorial decision-making: Tech. Rep. No. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

Freiburger TL, Jordan KL, Hilinski-Rosick CM (2019) A multivariate analysis of incarceration and sentence length decisions for older defendants. Crim Justice Policy Rev 30(7):1064–1085

Frenzel ED, Ball JD (2008) Effects of individual characteristics on plea negotiations under sentencing guidelines. J Ethnicity in Crim Justice 5(4):59–82

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2010) Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw 33(1):1–22

Frohmann L (1997) Convictability and discordant locales: Reproducing race, class, and gender ideologies in prosecutorial decisionmaking. Law Soc Rev 31(3):531

Garvey SP, Hannaford-Agor P, Hans VP, Mott NL, Munsterman GT, Wells MT (2004) Juror first votes in criminal trials. J Empir Leg Stud 1:371–399

Goeman J, Meijer R, Chaturvedi N (2018) L1 and L2 penalized regression models. Vignette R Package Penalized. URL http://cran. nedmirror. nl/web/packages/penalized/vignettes/penalized. pdf.

Grunwald B (2020) Distinguishing plea discounts and trial penalties. Georgia State Univ Law Rev 37(2):261–304

Hastie T, Qian J, Tay K (2016) An introduction to glmnet. https://cloud.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/vignettes/glmnet.pdf

Hayes AF, Krippendorff K (2007) Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas 1(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

Heller KJ (2006) The cognitive psychology of circumstantial evidence. Mich Law Rev 105:241–305

Henderson KS (2021) Examining the effect of case and trial factors on defense attorneys’ plea decision-making. Psychology, Crime and Law 27(4):357–382

Hoerl AE, Kennard RW (1970) Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 12(1):55–67

Johnson BD, Larroulet P (2019) The “distance traveled”: Investigating the downstream consequences of charge reductions for disparities in incarceration. Justice Q 36(7):1229–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1529250

Kassin SM (2012) Why confessions trump innocence. Am Psychol 67:431–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/a002812

Kassin SM, Neumann K (1997) On the power of confession evidence: an experimental test of the fundamental difference hypothesis. Law Hum Behav 21:469–484

Kelly WR, Pitman R (2018) Confronting underground justice: Reinventing plea bargaining for effective criminal justice reform. Rowan and Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Kim A (2015) Underestimating the trial penalty: an empirical analysis of the federal trial penalty and critique of the Abrams study. Mississippi Law J 84(5):1195–1256

Kipnis K (1976) Criminal justice and the negotiated plea. Ethics 86(2):93–106

Koehler JJ (2001) When are people persuaded by DNA match statistics? Law Hum Behav 25:493–513. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012892815916

Kramer GM, Wolbransky M, Heilbrun K (2007) Plea bargaining recommendations by criminal defense attorneys: Evidence strength, potential sentence, and defendant preference. Behav Sci Law 25(4):573–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.759

Kramer JH, Ulmer JT (2009) Sentencing guidelines: lessons from Pennsylvania. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, CO

Kurlychek MC, Johnson BD (2019) Cumulative disadvantage in the American criminal justice system. Ann Rev Criminol 2:291–319

Kutateladze BL, Andiloro NR, Johnson BD, Spohn CC (2014) Cumulative disadvantage: examining racial and ethnic disparity in prosecution and sentencing. Criminology 52(3):514–551

Kutateladze BL, Lawson VZ, Andiloro NR (2015) Does evidence really matter? An exploratory analysis of the role of evidence in plea bargaining in felony drug cases. Law and Human Behavior 39(5):431–442

Lafler v. Cooper 132 S. Ct. 1376 (2012). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/10-209.pdf

LaFree GD (1985) Adversarial and nonadversarial justice: a comparison of guilty pleas and trials. Criminology 23(2):289–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1985.tb00338.x

Landes WM (1971) An economic analysis of the courts. J Law and Econom 14(1):61–107. https://doi.org/10.1086/466704

Light MT (2014) The new face of legal inequality: Noncitizens and the long-term trends in sentencing disparities across US district courts, 1992–2009. Law Soc Rev 48(2):447–478

Light MT, Massoglia M, King RD (2014) Citizenship and punishment: the salience of national membership in US criminal courts. Am Sociol Rev 79(5):825–847

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA

Luna S, Redlich AD (2020) Unintelligent decision-making? the impact of discovery on defendant plea decisions. Wrongful Conviction Law Rev 1:314

Marquardt DW, Snee RD (1975) Ridge regression in practice. Am Stat 29(1):3–20

McAllister HA, Bregman NJ (1986) Plea bargaining by prosecutors and defense attorneys: a decision theory approach. J Appl Psychol 71(4):686

McCormick CT (1972) Handbook of the law of evidence, 2nd edn. West, St. Paul, MN

McCoy T, Salinas PR, Walker JT, Hignite L (2012) An examination of the influence of strength of evidence variables in the prosecution’s decision to dismiss driving while intoxicated cases. Am J Crim Justice 37(4):562–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-011-9141-3

McDonald GC (2009) Ridge regression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat 1(1):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.14

Melkumova LE, Shatskikh SY (2017) Comparing ridge and lasso estimators for data analysis. Procedia Eng 201:746–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.615

Miles J (2005) Tolerance and variance inflation factor. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC (eds) Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp 2055–2056

Miller HS, McDonald WF, Cramer JA (1980) Plea bargaining in the United States. United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Washington

Mnookin RH, Kornhauser L (1979) Bargaining in the shadow of the law: The case of divorce. Yale Law J 88(5):950–997. https://doi.org/10.2307/795824

Niedermeier KE, Kerr NL, Messe LA (1999) Jurors’ use of naked statistical evidence: exploring bases and implications of the Wells Effect. J Pers Soc Psychol 76:533–554

Omori M, Petersen N (2020) Institutionalizing inequality in the courts: decomposing racial and ethnic disparities in detention, conviction, and sentencing. Criminology 58(4):678–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12257

Padilla v. Kentucky, 130 S. Ct., 1472 (2010). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/09pdf/08-651.pdf

Petersen K, Redlich AD, Norris RJ (2020) Diverging from the shadows: explaining individual deviation from plea bargaining in the “shadow of the trial.” J Exp Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09449-4

Piehl AM, Bushway SD (2007) Measuring and explaining charge bargaining. J Quant Criminol 23(2):105–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-006-9023-x

Porter L (2020) Top trends in state criminal justice reform, 2019. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/top-trends-in-state-criminal-justice-reform-2019/

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Redlich AD, Bushway SD, Norris RJ (2016) Plea decision-making by attorneys and judges. J Exp Criminol 12(4):537–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9264-0

Redlich AD, Bibas S, Edkins VA, Madon S (2017) The psychology of defendant plea decision making. Am Psychol 72(4):339

Redlich AD, Yan S, Norris RJ, Bushway SD (2018) The influence of confessions on guilty pleas and plea discounts. Psychol Public Policy Law 24(2):147–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000144

Redlich AD, Zottoli T, Dezember A, Schneider R, Catlin M, Shammi S (in press) Emerging issues in the psycho-legal study of guilty pleas. In DeMatteo D, Scherr K (eds) The oxford handbook of psychology and law. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Reitz KR (1993) Sentencing facts: Travesties of real-offense sentencing. Stanford Law Review 45(3):523–574

Rhodes WM (1979) Plea bargaining: Its effect on sentencing and convictions in the District of Columbia. J Crim Law Criminol 70(3):360–375

Schklar J, Diamond SS (1999) Juror reactions to DNA evidence: errors and expectancies. Law Hum Behav 23:159–184. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022368801333

Schmidt J, Steury EH (1989) Prosecutorial discretion in filing charges in domestic violence cases. Criminology 27(3):487–510

Silge J, Chow F, Kuhn M (2021) Rsample: General resampling infrastructure. R package version 0.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rsample

Smith DA (1986) The plea bargaining controversy. J Crim Law Criminol 77(3):949–968. https://doi.org/10.2307/1143445

Smith CM, Goldrosen N, Ciocanel MV, Santorella R, Topaz CM, Sen S (2021) Racial disparities in criminal sentencing vary considerably across federal judges. Institute for the Quantitative Study of Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity, Inc., 501(c)3. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/

Spohn C (2018) Reflections on the exercise of prosecutorial discretion 50 years after publication of the challenge of crime in a free society. Criminol Public Policy 17(2):321–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12367

Spohn C, Holleran D (2001) Prosecuting sexual assault: a comparison of charging decisions in sexual assault cases involving strangers, acquaintances, and intimate partners. Justice Q 18(3):651–688

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer J, Kramer J (1998) The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36(4):763–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01265.x

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics, 5th edn. Pearson, Boston, MA

Taylor TS, Hosch HM (2004) An examination of jury verdicts for evidence of a similarity-leniency effect, an out-group punitiveness effect or a black sheep effect. Law Hum Behav 28(5):587–598

Ternès N, Rotolo F, Michiels S (2016) Empirical extensions of the lasso penalty to reduce the false discovery rate in high‐dimensional Cox regression models. Stat Med 35(15):2561–2573

Tibshirani R (1996) Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (methodol) 58(1):267–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x

Tonry M (1988) Sentencing guidelines and the model penal code. Rutgers Law J 19(3):823–848

Ulmer JT, Bader C, Gault M (2008) Do moral communities play a role in criminal sentencing? Evidence from Pennsylvania the Soc Q 49(4):737–768

Ulmer JT, Bradley MS (2006) Variation in trial penalties among serious violent offenses. Criminology 44(3):631–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00059.x

Ulmer JT, Eisenstein J, Johnson BD (2010) Trial penalties in federal sentencing: extra-guidelines factors and district variation. Justice Q 27(4):560–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820902998063

University of Virginia (2018) Population estimates for age, sex, race & Hispanic, and towns. https://demographics.coopercenter.org/population-estimates-age-sex-race-hispanic-towns

Wells GL (1992) Naked statistical evidence of liability: Is subjective probability enough? J Pers Soc Psychol 62:739–752

Winship C, Mare RD (1992) Models for sample selection bias. Ann Rev Sociol 18(1):327–350

Yan S (2020) What exactly is the bargain? The sensitivity of plea discount estimates. Justice Q. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1707856

Yan S, Bushway SD (2018) Plea discounts or trial penalties? Making sense of the trial-plea sentence disparities. Justice Q 35(7):1226–1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1552715

Yoo W, Mayberry R, Bae S, Singh K, He QP, Lillard JW Jr (2014) A study of effects of multicollinearity in the multivariable analysis. Int J Appl Sci Technol 4(5):9

Zottoli TM, Daftary-Kapur T, Winters GM, Hogan C (2016) Plea discounts, time pressures, and false-guilty pleas in youth and adults who pleaded guilty to felonies in new york city. Psychol Public Policy Law 22(3):250–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000095

Acknowledgements

This research was in part supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Justice. We are particularly grateful to Shawn Bushway, Jodi Quas, Amy Dezember, Skye Woestehoff, Megan Stoltz, and Melissa Manley. We also are indebted to the county court for their cooperation.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant #1603944) and the National Institute of Justice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Petersen, K., Redlich, A.D. & Wilson, D.B. Where is the Evidence? Comparing the Effects of Evidence Strength and Demographic Characteristics on Plea Discounts. J Quant Criminol 39, 919–949 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-022-09555-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-022-09555-8