Abstract

Objective

To demonstrate how visualization can aid in understanding crime rate data and provide new insights and hypotheses for some central criminological questions about homicide offending over time.

Methods

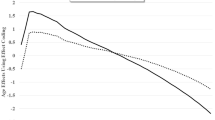

The research uses arrest data that is based on a mixture of single year age data and other age groupings to produce single years of age estimates of homicide offending for those 15–64 from 1964 to 2019. This data is then presented in surface plots, contour plots, and with graphs based on simple statistics to address four areas of research: the increase in homicide rates from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, the drop in homicide offending from the early 1990s to 2000, the epidemic of youth homicide, and the invariance of the homicide age-curve.

Results

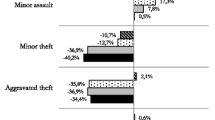

The epidemic of youth homicide (ages 15–24) lasts well into the period when homicide rates dropped in the 1990s. For most of the population (excluding those 15–24) the homicide drop is initiated around 1980 rather than the early 1990s. However, the homicide increase of mid-1960s to mid-1970s included increases in the homicide rate for both those 15–24 and those not in the 15–24 age group.

Conclusions

Researchers can learn much about important areas in criminology by examining the relationship between age and homicide offending using simple visualizations based on raw data and pursue what they learn using line graphs based on elementary statistics and simple statistical methods. Of course, complicated statistical methods are called for in many situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Quetelet (2003 [1831]) wrote about the age-crime curve and its relative invariance in 1831.

When I refer to youth, I will use the United Nations (United Nations 2021) and World Health Organization (WHO 2021) definitions of youth as those 15–24 years of age. This age range includes those with the highest homicide rates from 1964 to 2019 in the United States. Some literature define youth as juveniles (less than 18 years of age). In any case, during the epidemic of youth homicides, youth had a striking increase in homicide rates in comparison to those of older ages.

Importantly the number of homicides known to the police each year is quite close to the number of homicides that are reported in the Vital Statistics based on death certificates (see, for example, O’Brien 2019).

Supplementary Homicide Report data by age that is representative of the population of the United States is available from the mid-1970s. It is also based on arrest data, but has some additional details on the victim as well as the offender in particular incidents.

I use the same method with the Center for Disease Control (CDC 2021) data on the United States resident population for the years 1964–1989, which is categorized in five-year age groups. This data is not truncated at age 65 plus, so that I was able to use five five-year age groups in all of my estimates using the Sprague formula.

This coding indicates the identification problem in APCMC models in that being a specific age (\(i\)) and year (\(j\)) determine an observation’s birth cohort (\(I-i+j\)).

The rates per 100,000 for 18 year olds were 57 in 1991, 52 in 1992, 55 in 1993 and 52 in 1994.

The rate is calculated as the estimated number of homicide offenses for all age groups except for those 15–24 divided by the number of residents in the US not in the 15–24 age category times 100,000.

The deviations from their linear trend for periods and ages are also estimable functions.

It is the linear trends for ages, periods, and cohorts that create the identification problem in APCMC models.

These are residuals are from an APCMC model in which the homicide rate variable has been logged, which is common in most regression models that analyze homicide rates (because these rates are based on counts and they are skewed to the right). The proportion of the variance accounted for in the APCMC homicide model is .977.

The General Social Survey (GSS) is a project of the independent research organization NORC at the University of Chicago, with principal funding from the National Science Foundation.

References

Barker V (2010) Explaining the great American crime decline: a review of Blumstein and Wallman, Goldberger and Rosenfeld, and Zimring. Law Soc Inq 35:489–516

Baumer E (2008) An empirical assessment of the contemporary crime trends puzzle: a modest step toward a more comprehensive research agenda. In: Goldberger A, Rosenfeld R (eds) Understanding Crime Trends: Workshop Report. National Academies Press, Washington, pp 127–176

Baumer E, Wolff K (2014) Evaluating contemporary crime drop(s) in America New York City, and many other places. Justice Q 31:5–38

Bell A (2020) Age period cohort analysis: a review of what we should and shouldn’t do. Ann Hum Biol 47(2):208–217

Blumstein A (1995) Youth violence, guns, and the illicit-drug industry. J Crim Law Criminol 86:10–36

Blumstein A, Rosenfeld R (2008) Factors contributing to U.S. crime trends. National Research Council, Understanding Crime Trends: Workshop Report. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp 13–43

Blumstein A, Wallman J (2000) The recent rise and fall of American violence. In: Blumstein A, Wallman J (eds) The Crime Drop in America, Cambridge Studies in Criminology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–12

Blumstein A, Rivara FP, Rosenfeld R (2000) The rise and decline of homicide—and why. Annu Rev Public Health 21:505–541

Booth H (2001) Demographic techniques: data adjustment and correction. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB (eds) International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. New York, Elsevier, pp 3452–3456

Braga AA (2003) Serious youth gun offenders and the epidemic of youth violence in Boston. J Quant Criminol 19:33–54

Britt CL III (1992) Constancy and change in the U.S. age distribution of crime: a test of the "invariance hypothesis. J Quan Criminol 8:175–187

Browne A, Williams KR, Parker RN, Strom KJ, Barrick K (2014) Youth Homicide in the United States. In: Bruinsma G, Weisburd D (eds) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, New York

Calot G, Sardon JP (2004) Methodology for the Calculation of Eurostat’s Demographic Indicators Detailed Report by the European Demographic Observatory– EDO. Luxembourg office for official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg

CDC (2021) Population by age groups, race, and sex for 1960-97. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statab/pop6097.pdf retrieved Feb 12, 2021

CDC Wonder (2021) United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2019.html on Feb 14, 2021

Chilton R (1986) Age, sex, race, and arrest trends for 12 of the nation’s largest central cities. In: Byrne JM, Sampson RJ (eds) The Social Ecology of Crime. Springer, New York, pp 102–115

Clayton D, Schifflers E (1987) Models for temporal variation in cancer rates II: age-period-cohort models. Stat Med 6:468–481

Cook PJ, Laub JH (1998) The unprecedented epidemic in youth violence. Crime Justice 24:27–64

Cork D (1999) Examining space–time interaction in city-level homicide data: crack markets and the diffusion of guns among youth. J Quant Criminol 15:379–406

Donohue JJ (1998) Understanding the time path of crime. J Crim Law Criminol 88:1423–1451

Eisner M (2008) Modernity strikes back: a historical perspective on the latest increase in interpersonal violence (1960–1990). Int J Confl Violence 2:288–316

Elias N (1994) The civilizing process: sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, England

Farrington DP (1986) Age and crime. Crime Justice 7:189–250

FBI (1965–2020). Crime in the United States (1964–2019, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC

Fosse E, Winship C (2019) Analyzing age-period-cohort data: a review and critique. Ann Rev Sociol 45:467–492

Fox JA, Piquero AR (2003) Deadly demographics: population characteristics and forecasting homicide trends. Crime Delinq 49:339–359

Greenberg DF (1985) Age, crime, and social explanation. Am J Sociol 91:1–21

Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89:552–584

Holford TR (1983) The estimation of age, period, and cohort effects for vital rates. Biometrics 39:311–324

Kupper LL, Janis LM, Salama IA, Yoshizawa CN, Greenberg BG (1983) Age-period-cohort analysis: an illustration of the problems in assessing interactions in one observation per cell data. Commun Stat 12:2779–2807

La Free G (1998) Losing legitimacy: street crime and the decline of social institutions in America. Routledge, New York

LaFree G (1998) Social institutions and the crime bust of the 1990s. J Crim Law Criminol 88:1325–1368

Levitt SD (2004) Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. J Econ Perspect 18:163–190

Loeber R, Farrington DP (2014) Age-crime curve. The Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, New York, pp 12–18

Maltz MD (1998) Visualizing homicide: a research note. J Quant Criminol 14:397–410

Mason KO, Mason WM, Winsborough HH, Poole WK (1973) Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. Am Sociol Rev 38:242–258

Matthews B, Minton J (2018) Rethinking one of criminology’s ‘brute facts’: the age–crime curve and the crime drop in Scotland. Eur J Criminol 15:296–320

McDowall D (2019) The 2015 and 2016 U.S. homicide rate increases in context. Homicide Stud 23:225–242

Mennell S (2006) Civilizing processes. Theory Cult Soc 23:429–431

Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (1994) Crime and the American Dream. Wadsworth, Belmont California

Minton J, Vanderbloemen L, Dorling D (2013) Visualizing Europe’s demographic scars with coplots and contour plots. Int J Epidemiol 42:1164–1176

O’Brien RM (1989) Relative cohort size and age-specific crime rates: an age-period-relative-cohort-size model. Criminology 27:57–78

O’Brien RM (2014) Estimable functions of age–period–cohort models: a unified approach. Qual Quant 48:457–474

O’Brien RM (2019) Homicide arrest rate trends in the United States: the contributions of periods and cohorts (1965–2015). J Quant Criminol 35:211–236

O’Brien RM (2020) Estimable intra-age, intra-period, and intra-cohort effects in age-period-cohort multiple classification models. Qual Quant 54:1109–1127

O’Brien RM (2021) A simplified approach for establishing estimable functions in fixed effect age-period-cohort multiple classification models. Stat Med 40:1160–1171

O’Brien RM, Stockard J (2009) Can cohort replacement explain changes in the relationship between age and homicide offending? J Quant Criminol 25:79–101

O’Brien RM, Stockard J, Isaacson L (1999) The enduring effects of cohort characteristics on age-specific homicide rates, 1960–1995. Am J Sociol 104:1061–1095

Pinker S (2011) The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence has Declined. Penguin Books, New York

Porter LC, Bushway SD, Tsao HS, Smith HL (2016) How the U.S. prison boom has changed the age distribution of the prison population. Criminology 54:30–55

Quenelle A (2003) Research on the propensity for crime at different ages. In: Bean P (ed) Crime: Critical Concepts in Sociology. Taylor & Francis, London, pp 119–135

Reyes JW (2015) Lead exposure and behavior: effects on antisocial and risky behavior among children and adolescents. Econ Inq 53:1580–1605

Roeder O, Eisen L-B, Bowling J (2015) What caused the crime decline? Brennan Center for justice at New York University School of Law

Rosenfeld R, Messner SF (2009) The crime drop in comparative perspective: the impact of the economy and imprisonment on American and European burglary rates. Br J Sociol 60:445–471

Sampson RJ, Winter AS (2018) Poisoned development: assessing childhood lead exposure as a cause of crime in a birth cohort followed through adolescence. Criminology 56:225–432

Savolainen J (2000) Relative cohort size and age-specific arrest rates: a conditional interpretation of the Easterlin effect. Criminology 38:117–136

Spierenburg P (2001) Violence and the civilizing process: does it work? Crime History Soc 5:87–105

Sprague TB (1880) Explanation of a new formula for interpolation. J Inst Actuar 22:270–285

Steffensmeier DJ, Allen EA, Harer MD, Streifel C (1989) Age and the distribution of crime. Am J Sociol 94:803–831

Steffensmeier D, Streifel C, Shihadeh ES (1992) Cohort size and arrest rates over the life course: The Easterlin hypothesis reconsidered. Am Sociol Rev 57:306–314

Tcherni-Buzzeo M (2019) The great American Crime decline: possible explanations. In: Krohn MD, Lissotte A, Penly-Hall G (eds) Handbook of Crime and Deviance. Springer, New York

United Nations (2021) Definition of youth. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf. Accessed March 25th, 2021

Vaupel JW, Wang Z, Andreev KF, Yasin AL (1997) Population Data at a Glance. Odense University Press, Odense

Wellford CF (1973) Age composition and the increase in recorded crime. Criminology 11:61–70

WHO (2021) Adolescent health in the south-east Asia region. https://www.who.int/ southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health#:~:text=WHO%20defines%20' Adolescents'%20as%20individuals,age%20range%2010%2D24%20years. Accessed March 25th 2021.

Zimring FE (2006) The great American Crime Decline. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Brien, R.M. Visualizing Changes in the Age-Distributions of Homicides in the United States: 1964–2019. J Quant Criminol 39, 495–518 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-022-09543-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-022-09543-y