Abstract

Objectives

Over the last 40 years, considerable changes have occurred in both education and crime, and in this study, we examine the longer-term consequences of education for violence in communities. We argue that the impact of education on crime depends on the temporal and spatial context of educational levels. Specifically, we focus on whether the type of educational attainment matters and the broader historical context. We also examine whether these patterns are robust for different regions of the city and racial/ethnic compositions of neighborhoods.

Methods

Using longitudinal neighborhood data over 40 years in St. Louis, Missouri, we test whether education has consequences for violent crime with a series of two-way fixed effects models.

Results

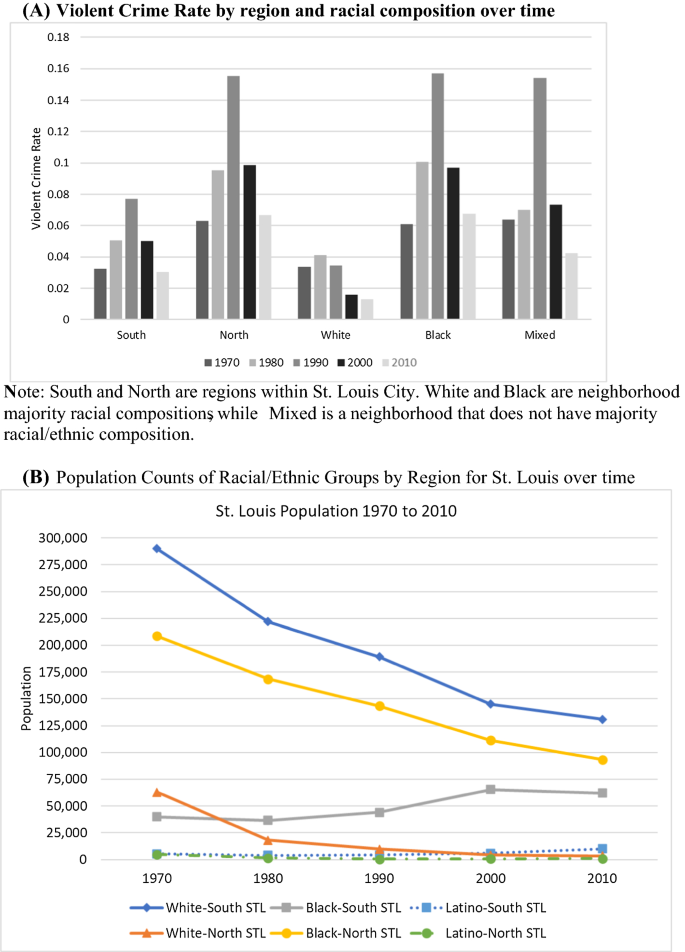

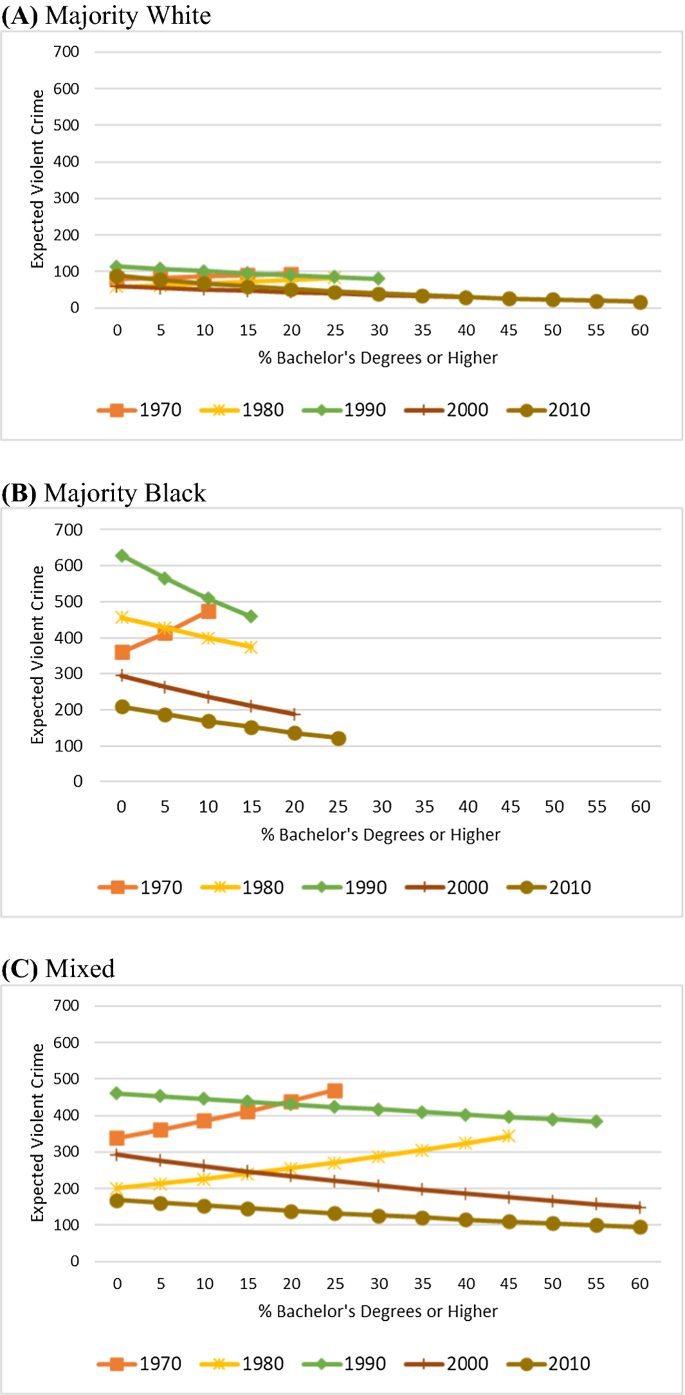

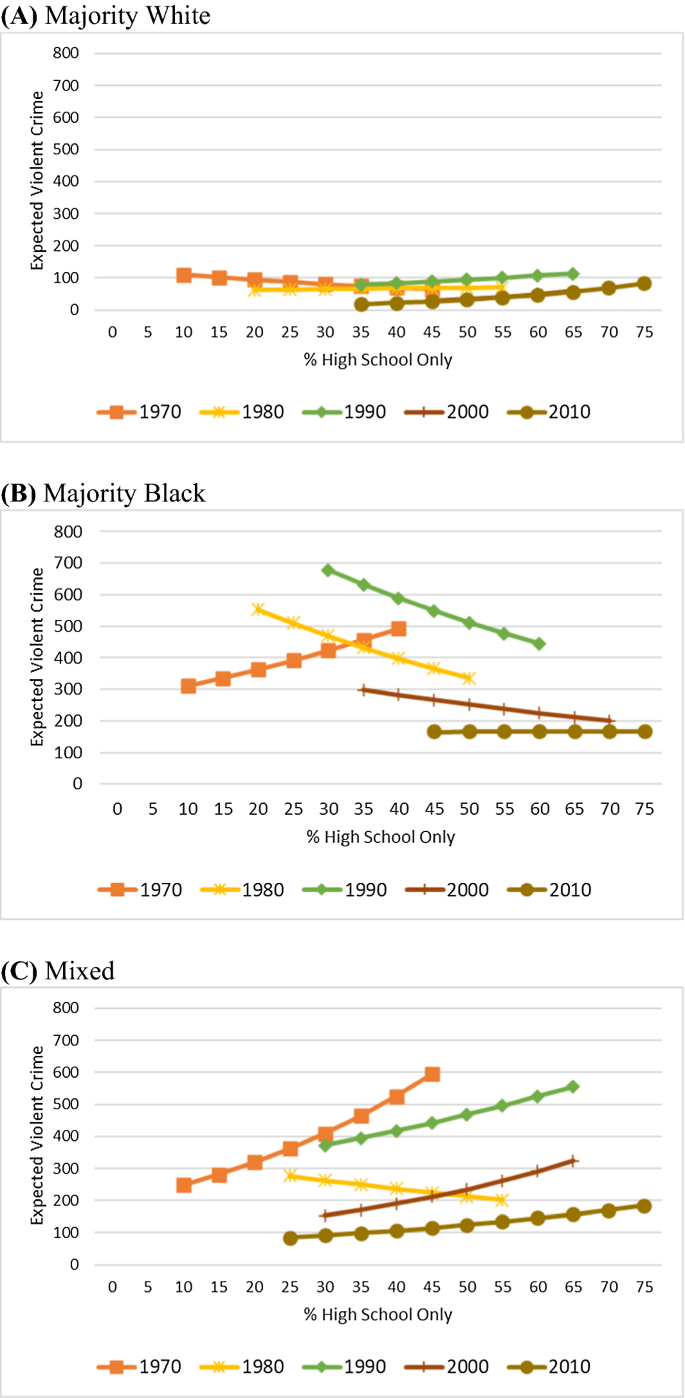

Neighborhoods with more college degrees in more recent time periods are generally associated with reductions in violent crime, especially in the white, southern region of the city. In contrast, neighborhoods with greater reliance on high school degrees were associated with violence reduction in the past, especially in the Black, northern part of the city, but the relationship no longer holds in the modern era. Both time and place therefore matter for education’s association with crime in neighborhoods.

Conclusion

The findings provide evidence that educational attainment has important consequences for neighborhood crime, but this relationship depends on the kind of education, historical temporal period, and region of the city. Overall, communities with more college degrees are consistently associated with reductions in violence in more recent decades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

09 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09537-2

Notes

Nevertheless, a challenge has emerged in the literature in regards to these systemic and social disorganization theories of neighborhood crime, which suggest that poor communities are organized (e.g., see Sánchez-Jankowski 2008; Whyte 1943), and other work argues that many places with strong kin and friendship ties can also have higher crime rates (Pattillo 1998; Sampson 2012).

Moreover, even amongst different kinds of universities (public vs. private), there is evidence of inequality in the spatial distribution of social friendships among students who attend schools (e.g., private school students often have a much broader spatial footprint in where students come from who attend, see Spiro et al. 2016).

We use 2005–2009 ACS data rather than the 2010 census since the ACS data are already in year 2000 tracts.

Census tracts are also a useful approach since neighborhood census data are not available in micro units at earlier decades but tract data is available, and tracts’ boundaries can be standardized between decades.

As of the 2000 census, there were 113 tracts for St. Louis, but four census tracts had zero population or low population (e.g., a tract with a large cemetery) and were omitted from the analyses. We use the same analytical sample for St. Louis that Peterson and Krivo 2010 used in their study. The sample sizes in the tables are 544 rather than 545, and this is because one tract in 1970 had missing data, and this observation was omitted from the analysis.

Specifically, blocks are mostly contained within the named neighborhoods, although tracts are relatively similar too. We first intersected the blocks with the named neighborhoods in ArcGIS, and we then merged in the block population data, and used it to apportion the crime data. To assess this procedure, we used our crime data from 2010 that has x–y coordinates. We put our 2010 data into the named neighborhood units and apportioned them into year 2000 units. As a comparison, we used the x–y coordinates of the 2010 crime data and aggregated them directly to 2000 census tracts. We then correlated the violent crime measures using the apportioned units and the crime data aggregated directly to 2000 census tracts. The correlation was .93, which suggests that this apportionment approach is reasonable.

As an assessment of the quality of these data, we compared the distributions of the counts of crime at each decade with the reported Uniform Crime Reports that are available at the city level for each time point. All data were quite similar with the reported uniform crime report data, and this gives us confidence in the quality of these data. Of course, these data also are subject to the issues of official police data with not all crimes being reported or recorded (Lynch and Addington 2007; MacDonald 2001). Yet, Baumer (2002) noted that these reporting practices are not related systematically to neighborhood characteristics, therefore suggesting that the coefficients are unbiased. We also do not focus on rape or sexual assault given well-known issues with this crime type.

We tested whether there were crime type differences amongst the different crime categories of violent crime by estimating separate models for homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery. The results were nearly identical and given the abundance of tables, we only show the results for our general measure of violent crime. Future research might also examine the consequences of education for other types of crime (i.e., property crime), as well as heterogeneity within various crime types (Kubrin and Herting 2003; Kubrin and Weitzer 2003).

For 1970 and 1980, the census asked about the number of years of school each person completed (e.g., high school 1 year, high school 2 years, high school 3 years, etc.). For 1990, 2000, and 2010, the census question changed to reflect the level of school completed and type of degree. For the 1970 and 1980 census, we follow the Census’ approach to compare educational attainment over time by only focusing on high school for 4 years completed (or higher) or college degree 4 years (or higher). While some prior work has examined ‘years of education’ (e.g. See Lafree et al. 1992), we do not use this approach for a few reasons. First, the census does not ask about years of education in 1990, 2000, or 2010, and abandoned this practice for the 1990 census (see Kominski and Adams 1994; Kominski and Siegel 1993). Second, we are primarily interested in the qualitative distinction and credential of a college degree (not number of years educated), and this implies nonlinear (categorical) change. Third, many students, particularly in the modern era, likely go to school for many years (e.g., 5 years to obtain a college degree) or part time, and thus they may have more years of education but without a degree, suggesting more measurement error if we used this approach.

As another approach, some research has created an economic disadvantage factor. We did not use this approach because we are interested in within neighborhood change over time, and thus we would be comparing relative standardized within unit changes over time. As such, these analyses would allow for possibility that changes in other neighborhoods driving some of the within unit change. Thus, a neighborhood could appear to be changing simply because of its position in the distribution of a neighborhood factor score. It is also more conceptually challenging to interpret over time, and there are few measures available to compute over the 40 year time period. We did test some ancillary models that created a factor score with poverty, unemployment, and single parent families, and the inclusion of this measure did not alter our main findings, giving us further confidence in our models. Finally, we also estimated models using only unemployment, and the results were substantively the same.

For 1970, the heterogeneity measure is only based on 4 categories since there is not a measure of the percent Asian in the Census for this decade. This group is thus combined with the other category.

Rather than focusing on heterogeneity, another approach would include measures of individual racial/ethnic groups. We tested this possibility, and given that Black and white residents are by far the largest groups in St. Louis, we estimated a series of ancillary models that included the % Black residents. The results were the same, and the % Black measure was not significant for any of the models. We also note that this measure is correlated with our disadvantage measure (.76 on average over time), and overall, this gives us further confidence in our results. Finally, We also test models in the paper that examine differences by racial/ethnic composition of the neighborhood.

Recent work on immigration shows it is protective for communities, particularly during the 1990’s crime decline (Martinez et al. 2010; Ousey and Kubrin 2018). One explanation for these findings would suggest that they are due in part to high educational achievement among many immigrants, and thus we control for immigration.

We account for the binning nature of the data (i.e., the census only asks about income categories) using the Pareto-linear procedure with the prln04.exe program (Nielsen and Alderson 1997). This measure is correlated with poverty on average over decades at .23.

We also estimated a series of ancillary models that did not include neighborhoods with less than 1000 residents. The results from these models were essentially identically to the models shown in the tables.

The random effects model is another approach to understanding change in neighborhoods over time, and this approach theoretically would be quite different since it assesses differences between neighborhoods. While we think this is an interesting research question, our focus is on within neighborhood change and the fixed effects have the added benefit of accounting for time stable unobservables. Nonetheless, we did perform as Hausman test that allows for testing systematic differences between random and fixed effects models. The test was significant, suggesting that fixed effects is both theoretically and empirically the better approach.

As ancillary models, we also estimated multilevel mixed effects models that included random effects for neighborhoods and time. For these models, we included a random intercept for each neighborhood and the effect of time was allowed to vary across each neighborhood as a random slope. The results from these models were substantively the same as those presented in the text, which further strengthens our findings.

It is well-known that Stata’s “xtnbreg, fe” command is not a true fixed effects model, and one approach to estimate fixed effects is to use dummy variables (Allison 2009). One challenge with this approach is what is often referred to as the ‘incidental parameters problem’. To assess this issue, we estimated models without using neighborhood dummy variables, but we included our neighborhood entity fixed effects through Stata’s estimation commands (i.e., xtpoisson, fe) and added time dummies, and the results were substantively the same, giving us further confidence in the results.

As another set of ancillary models, we included a lagged violent crime rate with all of our models. This measure did not alter the substantive pattern of results, and this further strengthens our findings.

We also tested models with a 65% majority threshold and the results were similar.

Other researchers have used a similar modeling strategy when using states as units to understand punishment over decades (Campbell et al. 2015; Greenberg and West 2001; Jacobs and Carmichael 2001). We did estimate ancillary models for each decade separately and the results were similar. Also, we note that one study used time series models of crime trends in cities from 1960’s to 2000 suggests that there is little evidence that crime trends are historically contingent (LaFree 1999; McDowall 2002; McDowall and Loftin 2005; see also Parker et al. 2017). We are not aware of any research to date that has examined the historically contingent nature of different neighborhood predictors on crime.

To study neighborhoods or micro places over time, some studies have employed group based trajectory models (Stults 2010; Weisburd et al. 2004). While this approach is reasonable for some research questions (see also Bauer 2007; Bollen and Brand 2010; Kreager et al. 2011; Martinez et al. 2010; Nagin and Tremblay 2005), we are interested in within neighborhood processes, but the studies that employ those trajectory models nearly always focus on between neighborhood differences in the types of trajectories. The group based trajectory models employed most often in the literature also do not account for potentially important time stable unobserved characteristics (which we do with our fixed effects), as well as baseline differences among neighborhoods. Finally, the fixed effects models allow for easily testing differences between discrete historical contexts. We are aware of no work testing period change with group based trajectory models in that the change is assumed to operate in the same way across the entire time period of study. In this paper, we explicitly test whether neighborhoods experienced a discrete change in different decades for education.

Collinearity was tested with Philip Ender’s Stata ado file: ‘collin’. All variance inflation factors were under 4, thus there is no evidence of an issue in regards to collinearity. We tested for outliers using studentized residuals from models estimated as linear regressions (the outcome was converted to a rate). We then estimated models without observations with studentized residuals greater than or less than 2, and the results were the same.

One possibility for future research is that many of the high crime neighborhoods are located on the boundary (Delmar Blvd) separating the north and south regions of St. Louis. As such, the position of a neighborhood within a region in tandem with the placement of boundaries may be important for crime patterns.

As one comparison between the map for violent crime (Fig. 1A) and racial/ethnic composition (Fig. 1B), as well as considering the average plots in “Appendix Fig. 7”, we see that Black and mixed neighborhoods generally have higher crime rates than white neighborhoods on average. But, the cold spots on the extreme end of the distribution are always in white neighborhoods over time, while the ‘hot spots’ are most often in majority white neighborhoods in the 1970’s, but in more recent decades they are located in majority Black or mixed neighborhoods. Moreover, many of the cold spots are largely surrounded by other white neighborhoods, while the Black and mixed neighborhood hot spots are often sharing a border between different racial/ethnic compositions (i.e., Black neighborhoods next to white neighborhoods or mixed neighborhoods next to Black neighborhoods), suggesting future research more explicitly consider these patterns as a part of a larger socio spatial process (see also Boessen and Hipp 2015). Further, some of the areas with no population near downtown (i.e., railroad tracks) and key road boundaries (i.e., Delmar Blvd.) effectively shape high crime hot spots.

As noted in Appendix, the correlation between poverty and bachelor’s degrees is − .19, suggesting these while correlated as would be expected, it is relatively modest.

Because the regions are time-invariant, these differences were previously differenced out in our fixed effects models (see also Bollen and Brand 2010). Although not shown in the tables, we estimated ancillary models that included interactions between region and each decade timepoint to assess whether the regions were statistically different over time in their consequences for crime. These models indicated that the most recent decades (2000 and 2010) were significantly different from earlier decades (1970, 1980, and 1990), suggesting that we are theoretically and empirically justified in assessing differences by region. As another approach, we removed both sets of fixed effects from the models, and estimated separate models for each timepoint. With these models we could include our indicator for region, and it was significant in all of the models. We also tested these models with indicators for various racial compositions of neighborhoods with a series of N-1 dummy variables (white, Black, or mixed), and the results showed differences over time by racial composition of neighborhood. Taken as a whole, these ancillary models indicate we are theoretically and empirically justified for our models by region and racial/ethnic composition of neighborhood.

We also estimated models without racial/ethnic heterogeneity in the models, and the results were the same.

Although we are interested in each individual period effect, we used Stata’s ‘testparm’ command to jointly test each set of interactions as a Wald test (see also Paternoster et al. 1998). The result of these tests are consistent with the results presented, suggesting overall differences in the effects in different time periods.

We also briefly point out that these race/ethnicity majority neighborhood analyses are essentially comparisons between other similar (i.e., within group) neighborhoods (i.e., comparing white majority neighborhoods with other white majority neighborhoods), but this approach does allow for seeing their effect when plotted.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that there are only 5.2% (N = 11) mixed neighborhoods in 1970 and 12.8% (N = 14) in 1980, but this grows to 33% (N = 36) by 2010 and the crime rates in these areas are still relatively high when compared to white neighborhoods.

We also tested models using unemployment (rather than poverty), and the results were substantively similar.

We also tested whether high school degrees act as a mediator between poverty and violence, and there was no evidence of any indirect effects of poverty on violence being mediated by high school degrees.

We also estimated these models without the lagged violent crime measure, and the results were substantively the same.

The data are available at ICPSR: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/RCMD/studies/27501.

References

Abbott A (2001) Time matters: on theory and method. University of Chicago, Chicago

Adams RE (1992) Is happiness a home in the suburbs? The influence of urban versus suburban neighborhoods on psychological health. J Community Psychol 20(4):353–371

Allison PD (2009) Fixed effects regression models. Vol. 160: SAGE Publications

Baltagi BH, Song SH, Koh W (2003) Testing panel data regression models with spatial error correlation. J Econom 117(1):123–150

Bauer DJ (2007) Observations on the use of growth mixture models in psychological research. Multivar Behav Res 42:757–786

Baumer EP (2002) Neighborhood disadvantage and police notification by victims of violence. Criminology 40(3):579–616

Baumer EP, Fowler C, Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (2021) Change in the spatial clustering of poor neighborhoods within U.S. counties and its impact on homicide: an analysis of metropolitan counties, 1980–2010. The Sociol Q, 1–25

Beckett K, Western B (2001) Governing social marginality: welfare, incarceration, and the transformation of state policy. Punishm Soc 3(1):43–59

Bellair PE (1997) Social interaction and community crime: examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology 35(4):677–703

Bennett PR (2011) The relationship between neighborhood racial concentration and verbal ability: An investigation using the institutional resources model. Soc Sci Res 40(4):1124–1141

Beyerlein K, Hipp JR (2006) From pews to participation: the effect of congregation activity and context on bridging civic engagement. Soc Probl 53(1):97–117

Boessen A, Hipp JR (2015) Close-ups and the scale of ecology: land uses and the geography of social context and crime. Criminology 53(3):399–426

Boessen A, Hipp JR, Butts CT, Nagle NN, Smith EJ (2017) The built environment, spatial scale, and social networks: Do land uses matter for personal network structure? Environ Plan B 45(3):400–416

Bollen KA, Brand JE (2010) A general panel model with random and fixed effects: a structural equations approach. Soc Forces 89(1):1–34

Burgess EW (1925) The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project. In: Park RE, Ernest WB, Roderick DM (eds), The city: suggestions for investigvation of human behavior in the urban environment. University of Chicago Press

Bursik RJ, Grasmick HG (1993) Neighborhoods & crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, New York

Bursik RJ Jr, Webb J (1982) Community change and patterns of delinquency. Am J Sociol 88(1):24–42

Campbell MC, Vogel M, Williams J (2015) Historical contingencies and the evolving importance of race, violent crime, and region in explaining mass incarceration in the United States. Criminology 53(2):180–203

Carnevale AP, Strohl J, Melton M (2015) What’s it worth? Georgetown University: https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/whatsitworth-complete.pdf

Census Bureau (2010). https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/tables/12s0229.pdf

Chetty R et al (2017) Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. NBER Working Paper No. 23618

Chilton RJ (1964) Continuity in delinquency area research: a comparison of studies for Baltimore, Detroit, and Indianapolis. Am Sociol Rev 29(1):71–83

Crutchfield RD, Glusker A, Bridges GS (1999) A tale of three cities: labor markets and homicide. Sociol Focus 32(1):65–83

Deane G, Messner SF, Stucky TD, McGeever KF, Kubrin CE (2008) Not ‘islands, entire of themselves’: exploring the spatial context of city-level robbery rates. J Quant Criminol 24:363–380

DeSilver D (2018) For most workers, real wages have barely budged for decades. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/

Domina T (2006) Brain drain and brain gain: rising educational segregation in the United States, 1940–2000. City Community 5(4):387–407

Ehrenhalt A (2012) The great inversion and the future of the American city: Vintage

Elhorst JP (2003) Specification and estimation of spatial panel data models. Int Reg Sci Rev 26(3):244–268

Elhorst JP (2014) Spatial econometrics: from cross-sectional data to spatial panels. Springer, Berlin

Ellen IG, Horn KM, Reed D (2019) Has falling crime invited gentrification? J Hous Econ 46:101636

Eller CC, DiPrete TA (2018) The paradox of persistence: explaining the black-white gap in bachelor’s degree completion. Am Sociol Rev 83(6):1171–1214

Elliott KC, Jones T (2021) Beyond dollars and cents. Obtained from: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/05/19/any-measure-value-higher-ed-must-take-account-advancement-social-justice-opinion

Elliott DS, Menard S, Rankin B, Elliott A, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D (2006) Good kids from bad neighborhoods: successful development in social context. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Farley JE (1995) Race still matters: the minimal role of income and housing cost as causes of housing segregation in St. Louis, 1990. Urban Aff Rev 31(2):244–254

Furtado K, Vargas C, Corbett L, Dwight D IV (2020) Still separate, still unequal: a call to level the uneven education playing field in St. Louis. Forward Through Ferguson. See http://stillunequal.org/files/FTF_StillUnequal_Report_2020_web.pdf

Gibbs JP, Martin WT (1962) Urbanization, technology, and the division of labor: international patterns. Am Sociol Rev 27(5):667–677

Gordon C (2009) Mapping decline: St. Louis and the fate of the American city. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Greenberg DF, West V (2001) State prison populations and their growth, 1971–1991. Criminology 39(3):615–654

Harlan C (2014) In St. Louis, Delmar Boulevard is the line that divides a city by race and perspective. Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/in-st-louis-delmar-boulevard-is-the-line-that-divides-a-city-by-race-and-perspective/2014/08/22/de692962-a2ba-4f53-8bc3-54f88f848fdb_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.8b8f66bd73c4

Hauser RM, Logan JA (1992) How not to measure intergenerational occupational persistence. Am J Sociol 97(6):1689–1711

Hillman NW (2016) Geography of college opportunity: the case of education deserts. Am Educ Res J 53(4):987–1021

Hipp JR (2007) Income inequality, race, and place: does the distribution of race and class within neighborhoods affect crime rates? Criminology 45(3):665–697

Hipp JR (2011) Violent crime, mobility decisions, and neighborhood racial/ethnic transition. Soc Probl 58(3):410–432

Hipp JR, Chamberlain AW (2015) Foreclosures and crime: a city-level analysis in Southern California of a dynamic process. Soc Sci Res 51:219–232

Hipp JR, Kane K (2017) Cities and the larger context: What explains changing levels of crime? J Crim Just 49:32–44

Hipp JR, Wickes R (2017) Violence in urban neighborhoods: a longitudinal study of collective efficacy and violent crime. J Quant Criminol 33:783–808

Hipp J, Yates D (2011) Ghettos, thresholds, and crime: Does concentrated poverty really have an accelerating increasing effect on crime? Criminology 49(4):955–990

Hirschfield PJ (2008) Preparing for prison? The criminalization of school discipline in the USA. Theor Criminol 12(1):79–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480607085795

Hirschfield PJ (2018) Schools and crime. Annu Rev Criminol 1(1):149–169

Hout M (2012) Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annu Rev Sociol 38(1):379–400

Hunter A (1975) The loss of community: an empirical test through replication. Am Sociol Rev 40(5):537–552

Hunter A (1985) Private, parochial and public social orders: the problem of crime and incivility in Urban communities. In Metropolis: Center and Symbol of Our Times, edited by P. Kasinitz. New York: New York University

Jacobs D, Carmichael JT (2001) The politics of punishment across time and space: a pooled time-series analysis of imprisonment rates. Soc Forces 80(1):61–89

Johnson O Jr (2010) Assessing neighborhood racial segregation and macroeconomic effects in the education of African Americans. Rev Educ Res 80(4):527–575

Kent SL, Jacobs D (2005) Minority threat and police strength from 1980 to 2000: a fixed-effects analysis of nonlinear and interactive effects in large U.S. Cities. Criminology 43(3):731–760

Kim J, Lee Y (2018) Does it take a school? Revisting the influence of first arrest on subsequent delinquency and educational attainment in a tolerant educational background. J Res Crime Delinq (Forthcoming)

Kohfeld CW, Sprague J (2006) Arrests as communications to criminals in St. Louis, 1970, 1972–1982: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor]

Kominski R, Andrea A (1994) Educational attainment in the United States: March 1993 and 1992. Current population reports. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

Kominski R, Siegel PM (1993) Measuring education in the current population survey. Mon Labor Rev 116:34

Kreager D, Lyons CJ, Hays ZR (2011) Urban revitalization and seattle crime, 1982–2000. Soc Probl 58(4):615–639

Krivo LJ, Peterson RD, Kuhl DC (2009) Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. Am J Sociol 114(6):1765–1802

Krivo LJ, Washington HM, Peterson RD, Browning CR, Calder CA, Kwan M-P (2013) Social isolation of disadvantage and advantage: the reproduction of inequality in urban space. Soc Forces 92(1):141–164

Kubrin CE, Herting JR (2003) Neighborhood correlates of homicide trends: an analysis using growth-curve modeling. Sociol Q 44(3):329–350

Kubrin CE, Weitzer R (2003) Retaliatory homicide: concentrated disadvantage and neighborhood culture. Soc Probl 50(2):157–180

Kupchik A (2010) Homeroom security: school discipline in an age of fear, vol 6. NYU Press, New York

LaFree G (1999) Declining violent crime rates in the 1990s: predicting crime booms and busts. Annu Rev Sociol 25:145–168

LaFree G, Drass KA (1996) The effect of changes in intraracial income inequality and educational attainment on changes in arrest rates for African Americans and Whites, 1957–1990. Am Sociol Rev 61(4):614–634

LaFree G, Drass KA, O’Day P (1992) Race and crime in Postwar America: determinants of African-American and White Rates, 1957–1988. Criminology 30(2):158–185

LaFree G, Baumer EP, O’Brien R (2010) Still separate and unequal? A city-level analysis of the black-white gap in homicide arrests since 1960. Am Sociol Rev 75(1):75–100

Land KC, McCall PL, Cohen LE (1990) Structural covariates of homicide rates: Are there any invariances across time and social space? Am J Sociol 95(4):922–963

Lemieux T (2006) Postsecondary education and increasing wage inequality. Am Econ Rev 96(2):195–199

Levin A, Rosenfeld R, Deckard M (2017) The law of crime concentration: an application and recommendations for future research. J Quant Criminol 33:635–647

Levy BL (2018) Heterogeneous impacts of concentrated poverty during adolescence on college outcomes. Soc Forces 98(1):147–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy116

Levy BL, Owens A, Sampson RJ (2019) The varying effects of neighborhood disadvantage on college graduation: moderating and mediating mechanisms. Sociol Educ 92(3):269–292

Light MT, Thomas JT (2019) Segregation and violence reconsidered: Do whites benefit from residential segregation? Am Sociol Rev 84(4):690–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419858731

Light MT, Ulmer JT (2016) Explaining the gaps in white, black, and Hispanic violence since 1990 accounting for immigration, incarceration, and inequality. Am Sociol Rev 81(2):290–315

Lochner L, Moretti E (2004) The effect of education on crime: evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. Am Econ Rev 94(1):155–189

Logan JR, Stults BJ (2011) The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: New findings from the 2010 census. Census brief prepared for Project US2010

Logan JR, Zhang W, Chunyu MD (2015) Emergent Ghettos: black neighborhoods in New York and Chicago, 1880–1940. Am J Sociol 120(4):1055–1094

Lynch JP, Addington LA (eds) (2007) Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and UCR. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

MacDonald Z (2001) Revisiting the dark figure. Br J Criminol 41(1):127–149

Machin S, Marie O, Vujić S (2011) The crime reducing effect of education. Econ J 121(552):463–484

Martinez R, Stowell JI, Lee MT (2010) Immigration and crime in an era of transformation: a longitudinal analysis of homicides in San Diego Neighborhoods, 1980–2000*. Criminology 48(3):797–829

Martinez R, Stowell JI, Iwama JA (2016) The role of immigration: race/ethnicity and San Diego homicides since 1970. J Quant Criminol 32(3):471–488

Massey DS (1994) Getting away with murder: segregation and violent crime in urban America. U Pa l Rev 143:1203

McDonald S (2011) What’s in the “old boys” network? Accessing social capital in gendered and racialized networks. Soc Netw 33(4):317–330

McDowall D (2002) Tests of nonlinear dynamics in U.S. homicide time series, and their implications. Criminology 40(3):711–736

McDowall D, Loftin C (2005) Are U.S. crime rate trends historically contingent? J Res Crime Delinq 42(4):359–383

McKinnish T, Walsh R, Kirk White T (2010) Who Gentrifies low-income neighborhoods? J Urban Econ 67(2):180–193

Metzger MW, Fowler PJ, Swanstrom T (2018) Hypermobility and educational outcomes: the case of St. Louis. Urban Educ 53(6):774–805

Millo G, Piras G (2012) splm: spatial panel data models in R. J Stat Softw 47(1):1–38

Morris M (2016) Pushout: the criminalization of Black girls in schools. The New Press, New York

Nagin DS, Tremblay RE (2005) From seduction to passion: a response to Sampson and Laub. Criminology 43(4):915–918

Neil R, Sampson RJ (2021) The birth lottery of history: arrest over the life course of multiple cohorts coming of age, 1995–2018. Am J Sociol 126(5):1127–1178

Nordin M (2017) Does eligibility for tertiary education affect crime rates? Quasi-experimental evidence. J Quant Criminol (Forthcoming)

Ousey GC, Kubrin CE (2018) Immigration and crime : assessing a contentious issue. Annu Rev Criminol 1

Papachristos AV, Smith CM, Scherer ML, Fugiero MA (2011) More coffee, less crime? The relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City Community 10(3):215–240

Parker K (2008) Unequal crime decline: theorizing race, urban inequality, and criminal violence. New York University Press, New York

Parker KF, Mancik A, Stansfield R (2017) American crime drops: investigating the breaks, dips and drops in temporal homicide. Soc Sci Res 64:154–170

Parks-Yancy R (2006) The effects of social group membership and social capital resources on careers. J Black Stud 36(4):515–545

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A (1998) Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36(4):859–866

Pattillo ME (1998) Sweet mothers and gangbangers: Managing crime in a black middle-class neighborhood. Soc Forces 76(3):747–774

Paxton P, Hipp JR, Marquart-Pyatt S (2011) Nonrecursive models: endogeneity, reciprocal relationships, and feedback loops, quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage, Los Angeles

Perrin A, Gillis A (2019) How college makes citizens: higher education experiences and political engagement. Socius 5:1–16

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ (2010) Divergent social worlds: neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. Russell Sage, New York

Pfeffer FT (2018) Growing wealth gaps in education. Demography. In Press, New York

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster, New York

Raftery AE (1995) Bayesian model selection in social research. In: Sociological methodology 1995, Vol 25

Reardon SF (2011) The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: new evidence and possible explanations. Whither opportunity 91–116

Reardon SF (2016) School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 2(5):34–57

Sampson RJ (1993) Linking time and place: dynamic contextualism and the future of criminological inquiry. J Res Crime Delinq 30(4):426–444

Sampson RJ (2002) Transcending tradition: new directions in community research. Chicago Style Criminol 40(2):213–230

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago, Chicago

Sampson RJ, Byron Groves W (1989) Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol 94(4):774–802

Sánchez-Jankowski M (2008) Cracks in the pavement: social change and resilience in poor neighborhoods. University of California Press, California

Schuerman L, Kobrin S (1986) Community careers in crime. Crime Justice 8:67–100

Sharkey P (2013) Stuck in place: urban neighborhoods and the end of progress toward racial equality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Slater T (2013) your life chances affect where you live: a critique of the ‘cottage industry’ of neighbourhood effects research. Int J Urban Reg Res 37(2):367–387

Small ML, Manduca RA, Johnston WR (2018) Ethnography, neighborhood effects, and the rising heterogeneity of poor neighborhoods across cities. City Community 17(3):565–589

Smith EJ, Marcum CS, Boessen A, Almquist ZW, Hipp JR, Nagle NN, Butts CT (2015) The relationship of age to personal network size, relational multiplexity, and proximity to alters in the western United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 70(1):91–99

Spiro ES, Almquist ZW, Butts CT (2016) The Persistence of division geography, institutions, and online friendship ties. Socius Sociol Res Dyn World 2:1–15

Stewart R, Uggen C (2020) Criminal records and college admissions: a modified experimental audit. Criminology 58(1):156–188

Stock JH, Watson MW (2007) Introduction to econometrics. Addison Wesley, Boston

Stuart BA, Taylor EJ (2021) The effect of social connectedness on crime: evidence from the great migration. Rev Econ Stat 103(1):18–33

Stults BJ (2010) Determinants of Chicago neighborhood homicide trajectories: 1965–1995. Homicide Stud 14(3):244–267

Swaroop S, Morenoff JD (2006) Building community: the neighborhood context of social organization. Soc Forces 84(3):1665–1695

Sweeten G (2006) Who will graduate? Disruption of high school education by arrest and court involvement. Justice Q 23(4):462–480

Taub RP, Surgeon GP, Lindholm S, Otti PB, Bridges A (1977) Urban voluntary associations, locality based and externally induced. Am J Sociol 83(2):425–442

Taylor RB (2015) Community criminology: fundamentals of spatial and temporal scaling, ecological indicators, and selectivity bias. NYU Press, New York

Tighe JR, Ganning JP (2015) The divergent city: unequal and uneven development in St. Louis. Urban Geogr 36(5):654–673

Torche F (2011) Is a college degree still the great equalizer? Intergenerational mobility across levels of schooling in the United States. Am J Sociol 117(3):763–807

Van Tran, C, Graif C, Jones AD, Small ML, Winship C (2013) Participation in context: neighborhood diversity and organizational involvement in Boston. City Community 12(3):187–210

Velez MB (2001) The role of public social control in urban neighborhoods: a multilevel analysis of victimization risk. Criminology 39(4):837–863

Velez MB, Krivo LJ, Peterson RD (2003) Structural inequality and homicide: an assessment of the black-white gap in killings. Criminology 41:645–672

Webber HS, Swanstrom T (2014) Rebound neighborhoods in older industrial cities: the story of St. Louis. Public Policy Research Center, St. Louis

Weisburd D (2015) The law of crime concentration and the criminology of place. Criminology 53(2):133–157

Weisburd D, Bushway S, Lum C, Yang S-M (2004) Trajectories of crime at places: a longitudinal study of street segments in the City of Seattle. Criminology 42(2):283–321

Weitzman A (2018) Does increasing women’s education reduce their risk of intimate partner violence? Evidence from an education policy reform. Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12181

Wenger MR (2019) Omitted level bias in multilevel research: an empirical test distinguishing block-group, tract, and city effects of disadvantage on crime. Justice Q. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1649449

Western B, Kleykamp M, Rosenfeld J (2006) Did falling wages and employment increase U.S. imprisonment? Soc Forces 84(4):2291–2311

Whyte WF (1943) Street corner society: the social structure of an Italian Slum. University of Chicago, Chicago, p 1943

Wickes R, Hipp J, Sargeant E, Mazerolle L (2017) Neighborhood social ties and shared expectations for informal social control: Do they influence informal social control actions? J Quant Criminol 33(1):101–129

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was obtained from the University of Missouri St. Louis through the School of Public Policy’s Creating Whole Communities Fellowship and though the College of Arts and Sciences Research Grant Program. We also thank Lee Slocum for insightful comments on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The figure 3 (A) and (B) have been corrected.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boessen, A., Omori, M. & Greene, C. Long-Term Dynamics of Neighborhoods and Crime: The Role of Education Over 40 Years. J Quant Criminol 39, 187–249 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09528-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09528-3