Abstract

Objectives

There is a long-standing history of protests in response to police killings of African American citizens. However, it remains a largely unanswered question as to whether these protest events have had any impact on subsequent police killings of African American civilians. To answer this question, we turn to the over 700 racial uprisings that occurred in the 1960s and early 1970s that were largely triggered by negative and often violent interactions between the African American community and police.

Methods

To determine the impact of racial uprisings on police killings of civilians, we conduct an event-study analysis with a robust set of controls. We employ data on civilian deaths by legal intervention by race, county-level uprising occurrence, and county demographic characteristics. We take advantage of variation in the location and timing of a county’s first uprising to determine the impact of uprisings on police killings of civilians. Our identification strategy relies on pre-existing trends in deaths by legal intervention being uncorrelated with the date of the first uprising in a county.

Results

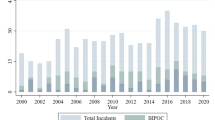

The results show that counties saw a marked increase in both non-white and white deaths due to legal intervention in the years immediately following an uprising. This initial increase is substantially larger for non-whites relative to white civilians. Deaths due to legal intervention for non-white and white civilians diverge over the medium-to-long run. Non-white deaths resulting from legal intervention remain elevated after nearly a decade while deaths of whites revert to their pre-existing trend after a handful of years. Additional analysis regarding the impact of uprisings on policing shows that total crime and police employment do not change in a significant manner over the long run, however, officers are more likely to be killed or injured on duty.

Conclusions

The results clearly show that historical protest resulted in an increase in civilian deaths by legal intervention regardless of race in the short-run and a seemingly permanent increase in killings of non-white over the medium-to-long run. These results paint a depressing picture in which uprisings represent a structural change in police-civilian relations, adversely affecting white civilians in the short-run and non-white civilians in the short and long-run.

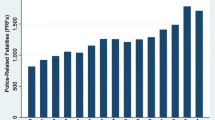

Source: Vital statistics multiple-cause of death files (US DHHS and ICPSR 2007). The vertical axis corresponds to the total number of deaths due to legal intervention by race

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It has been documented by Updegrove et al. (2018) that #BlackLivesMatter received substantially more public support in states with larger numbers of police shootings.

These data are currently being digitized by a team at the University of Victoria’s Racial Uprisings Lab under the direction of the two authors, covering the entire 1992–2017 period.

The NVSS is known to substantially undercount the number of civilians killed by law enforcement, but this is the only dataset available covering the time period of study. This is discussed in greater depth later in the paper along with the empirical implications.

For example, Washington DC experienced over a dozen riots over the 7-year period. Even a much smaller community like Benton Harbor, MI witnessed three riots.

Sociologists have advanced a number of theories as to the underlying causes of the 1960s riots, although there is little consensus the causes. Lieberson and Silverman (1965) believed that a lack of access to political representation was a driving source of riots as there few other mechanisms to convey grievances. Berkowitz (1968) argued that the progress of the Civil Rights era may have heightened expectations for progress, which when not met resulted in violence. Downes (1968) believed that a lack of integration into society made rioting more acceptable as a path to airing grievances. Myers (1997), building off of earlier work by Spilerman (1970, 1971, 1976) sought to empirically evaluate many of these theories, finding little evidence in their favor and, instead, pointing to ethnic competition and diffusion as causes. Carter (1987) finds that having too few or too many police officers can also increase the likelihood of triggering a riot. Economists such as Gunning (1972) and DiPasquale and Glaeser (1998) have similarly sought to explain the rioting decision in a rational choice framework.

There is also evidence that police treat African American protest very differently than those held by white Americans (Davenport et al 2011). Police are much more likely to be present at Black protests and to take direct action, which may in turn make an eruption of violence more likely.

For example, if uprisings were viewed as a form of costly retaliation to police use of force on the civilian population.

Political power gain by African American in large cities is primarily a result of black migration into urban areas and white flight to the suburbs. Both black migration and white flight began well before the 1960s, but racial uprisings may have accelerated white flight.

For robustness, we also consider specifications using the date of a county’s most severe uprisings, although we believe these results to be less precisely identified than those surrounding the occurrence of a first riot. More often than not, a county’s first riot is also its most severe riot.

Focusing on the timing is important as results from Updegrove et al. (2018) suggest that protests are more likely to occur and have greater participation in areas with greater levels of police violence against civilians.

See Jacobson et al. (1993).

Urban-by-year fixed effects are constructed by interacting year indicator variables with five categories of a county’s population share in urban areas, u: 0, 0 < u < 25, 25 ≤ u < 50, 50 ≤ u < 75, 75 ≤ u ≤ 100. This captures the differential utilization of police resources and changes in use of force with varying degrees of urbanization.

These data were kindly provided to us by Collins and Margo (2007) who used this data in their groundbreaking on the impact of the 1960s uprisings on African American property values.

These data exclude deaths due to legal execution.

It is important to note that the Vital Statistics recording of deaths by law enforcement contain many shortcomings related to completeness and accuracy due to political pressure and heterogeneity in data collection methods as a result of the voluntary nature of ICD coding (Sherman and Langworthy 1979; Fyfe 2002; Loftin et al. 2003). Despite these shortcomings, the Vital Statistics remains the most consistent and complete collection of deaths by law enforcement intervention for the time period of interest and a reliable source of police homicides for regression analysis (Sherman and Langworthy 1979). Moreover, heterogeneity in the recording of civilian deaths due to law enforcement is captured by county fixed effects assuming data collection efforts vary across counties but are time-invariant.

It is important to note that, although the number of police killings of civilians is quite similar in the 1960s, non-white deaths per non-white population is considerably higher than white deaths per white population.

Propensity scores are calculated using covariates in Table 1. Weights are rescaled to sum to one for non-rioting counties and rioting counties all receive the same weight (1/N, where N is the number of rioting counties).

Our inability to link riots to growth rates in police killings of non-white civilians is contrary to Williamson et al (2018) finding that BLM protest activity is correlated with previous killings of African Americans. This could be a matter of methodology or the fact that BLM protests are starkly different from the 1960s uprisings.

For non-white deaths, the population weights refer to the 1960 non-white population. Similarly, for the analysis of white deaths, the population weights refer to the 1960 white population. Weighted least squares is used to make error term homoscedastic. Results without population weights are available upon request.

Collins and Margo (2007) highlight the idiosyncrasies of the 1960 uprisings, detailing how routine event escalate into wide-spread riots due to unforeseen exchanges or interpretations of exchanges between the police and the black community.

This limits us to the 272 counties across the United States that experienced at least one riot over the period.

The pre-treatment effects are also statistically significant in this case and we are worried that the common trend assumption fails when imposing a non-linear model. We use the Poisson model to highlight the robustness of our results, but we use ordinary least squares throughout our analysis. We do this because (1) the common trends assumption, (2) the independence of occurrence condition of the Poisson model likely does not hold, and (3) over-dispersion will reduce the size of the standard errors, potentially leading to statistically significant joint pre-treatment and post-treatment effects. The main take away from the Poisson regressions is that the estimated joint pre-treatment and post-treatment effects from the Poisson regression have the same sign as the ordinary least squares regressions. Relatedly, see Athey and Imbens (2006) for a discussion of non-linear difference-in-difference modeling using a non-parametric approach. They propose a non-parametric model that provides a counterfactual distribution to identify the impact of a policy variable (treatment).

In particular, the results in Boustan (2010) suggest that while white-flight post-1960 was almost entirely concentrated amongst cities that experienced an uprising in contrast to the phenomenon pre-1960.

Population is constructed by interpolating 1960 census population to 1968 population provided by SEER. Many of the cities experienced their first riot prior to 1968, therefore these results must be viewed with caution.

It is important to note that county level crime statistics, police employment levels, and police killed on duty suffers severely from underreporting by local police agencies and inconsistent reporting due to the voluntary nature of the FBI Uniform Crime Reports data collection efforts. Results are to be interpreted with caution.

References

Abadie A (2005) Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. Rev Econ Stud 72(1):1–19

Alpert GP, MacDonald JM (2001) Police use of force: an analysis of organizational characteristics. Justice Q 18(2):393–409

Ariel B, Farrar WA, Sutherland A (2015) The effect of police body-worn cameras on use of force and citizens’ complaints against the police: a randomized controlled trial. J Quant Criminol 31:509

Athey S, Imbens GW (2006) Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-difference models. Econometrica 74(2):431–497

Bailey MJ, Goodman-Bacon A (2015) The war on poverty’s experiment in public medicine: community health centers and the mortality of older Americans. Am Econ Rev 105(3):1067–1104

Barber C, Azrael D, Cohen A, Miller M, Thymes D, Wang DE, Hemenway D (2016) Homicides by police: comparing counts from the national violent death reporting system, vital statistics, and supplementary homicide reports. Am J Public Health 106(5):922–927

Bauman R (2008) Race and the war on poverty: from Watts to east L.A. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK

Bejan V, Hickman M, Parkin WS, Pozo VF (2018) Primed for death: law enforcement-citizen homicides, social media, and retaliatory violence. PLoS ONE 13(1):e0190571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190571

Berkowitz L (1968) The study of urban violence: some implications of laboratory studies of frustration and aggression. Am Behav Sci 11(4):14–17

Blalock HM (1967) Toward a theory of minority-group relations. Wiley, New York

Boustan LP (2010) Was postwar suburbanization’white flight’? Evidence from the black migration. Q J Econ 125(1):417–443

Carter GL (1986) The 1960s black riots revisited: city level explanations of their severity. Sociol Inquiry 56(2):210–228

Carter GL (1987) Local police force size and the severity of the 1960s black rioting. J Confl Resolut 31(4):601–614

Chalfin A, McCrary J (2018) Are U.S. cities underpoliced? theory and evidence. Rev Econ Stat 100(1):167–186

Cloninger DO (1991) Lethal police response as a crime deterrent: 57-city study suggests a decrease in certain crimes. Am J Econ Sociol 50(1):59–69

Collins WJ, Margo R (2007) The economic aftermath of the 1960’s riots in American cities: evidence from property values. J Econ Hist 67(4):849–883

Collins WJ, Smith FH (2007) A neighborhood-level view of riots, property values, and population loss: Cleveland 1950–1980. Explor Econ Hist 44(3):365–386

Cunningham JP (2018) The language of the unheard: legal services and the 1960s race riots. Working paper, University of Memphis, Memphis

Cutler DM, Glaesar EL, Vigdor JL (1999) The rise and decline of the American ghetto. J Polit Econ 107(3):455–506

Davenport C, Soule SA, Armstrong DA II (2011) Protesting while black? The differential policing of American activism, 1960 to 1990. Am Sociol Rev 76(1):152–178

Desmond M, Papachristos AV, Kirk DS (2016) Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. Am Sociol Rev 81(5):857–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416663494

Diegelman RF (1982) Federal financial assistance for crime control: lessons of the LEAA experience. J Criminal Law Criminol 73(3):994–1011

DiNardo J, Fortin NM, Lemieux T (1996) Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages, 1973–1992: a semiparametric approach. Econometrica 64(5):1001–1044. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171954

DiPasquale D, Glaeser EL (1998) The Los Angeles riot and the economics of urban unrest. J Urban Econ 43(1):52–78

Downes BT (1968) Social and political characteristics of riot cities: a comparative study. Soc Sci Q 49(3):504–520

Feldman JM, Gruskin S, Coull BA, Krieger N (2017) Quantifying underreporting of law-enforcement-related deaths in United States vital statistics and news-media-based data sources: a capture–recapture analysis. PLoS Med 14(10):e1002399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002399

Fryer RG (2016) An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. NBER working paper series, No. 22399, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Fyfe JJ (2002) Too many missing cases: holes in our knowledge about police use of force. Justice Res Policy 4(1–2):87–102

Gillezeau R (2015) Did the war on poverty stop the 1960s race riots? Working paper, University of Victoria, Victoria

Gross N, Mann M (2017) Is there a “Ferguson Effect?” Google searches, concern about police violence, and crime in U.S. cities, 2014–2016. Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117703122

Gunning PJ (1972) An economic approach to riot analysis. Public Choice 13:31–46

Halloran R (1971) Florida governor charges misuse of U.S. grants. The New York Times, pp 30

Harris FR, Wilkins RW (1988) Quiet riots: race and poverty in the United States, New York. Pantheon Books, NY

Hinton E (2016) From the war on poverty to the war on crime: making of mass incarceration in America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Horrock NM (1976) Why lots of money didn’t end lots of crime: a safe streets act, but few safe streets. New York Times, pp. 201

Horowitz JL (2001) The bootstrap. In: Leamer EE, Heckman JJ (eds) Handbook of econometrics, vol V. Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam

ICPSR (1981) County and city data book (United States) consolidated file: city data 1944–1977, technical documentation. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor

Jacobs D (1998) The determinants of deadly force: a structural analysis of police violence. Am J Sociol 103(4):837–862

Jacobs D, O’Brien RM (1998) The determinants of deadly force: a structural analysis of police violence. Am J Sociol 103(4):837–862

Jacobson LS, LaLonde RJ, Sullivan DG (1993) Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am Econ Rev 83(4):685–709

Jeong J, Maddala GS (1993) A perspective on application of bootstrap methods in econometrics. In: Rao CR, Vinod HD (eds) Handbook of statistics, vol 11. Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam, pp 573–610

King MC (2003) Race riots and black economic progress. Rev Black Polit Econ 30(4):51–66

Lieberson S, Silverman AR (1965) The precipitants and underlying conditions of race riots. Am Sociol Rev 30(6):887–898

Loftin C, Wiersema B, McDowall D (2003) Underreporting of justifiable homicides committed by police officers in the United States, 1976–1998. Am J Public Health 93(7):1117–1121

Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A, Potter F, Sharma A, Knopov A, Siegel M (2018) The relationship between structural racism and black-white disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. J Natl Med Assoc 110(2):106–116

Myers DJ (1997) Racial rioting in the 1960S: an event history analysis of local conditions. Am Sociol Rev 62(1):94–112

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968) Report of the national advisory commission on civil disorder. Bantom Books, New York

O’Reilly K (1988) The FBI and the politics of the riots, 1964–1968. J Am Hist 75(1):91–114

Olzak SJ (1990) The political context of competition: lynching and urban racial violence, 1882–1914. Soc Forces 69:395–421

Olzak SJ (1992) The dynamics of ethnic competition and conflict. Stanford University Presss, Stanford

Olzak SJ (2015) Ethnic collective action in contemporary urban United States—data on conflicts and protests, 1954-1992. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34341.v1

Pang M-S, Valou PA (2016) Armed with technology: the impact on fatal shootings by the police (September 8, 2016). Fox School of Business Research Paper No. 16-020

Pyrooz DC, Decker SH, Wolfe SE, Shjarback JA (2016) Was there a ferguson effect on crime rates in large U.S. cities? J Criminal Justice 46:1–8

Quinn B (2014) The nation’s two measures of homicide. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington DC

Rahtz H (2016) Race, riots, and the police. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder

Santain L (2013) Borders of equality: the NAACP and the Baltimore civil rights struggle, 1914–1970. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson

Sears DO, McConahay JB (1973) The politics of violence; the new urban blacks and the Watts riot. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Sherman LW, Langworthy RH (1979) Measuring homicide by police officers. J Criminal Law Criminol 70(4):546

Singer BD, Osborn RW, Geschwender JA (1970) Black rioters; A study of social factors and communication in the Detroit riot. Heath Lexington Books, Lexington

Spilerman S (1970) The causes of racial disturbances: a comparison of alternative explanations. Am Sociol Rev 35(4):627–649

Spilerman S (1971) The causes of racial disturbances: test of an explanation. Am Sociol Rev 36(3):427–442

Spilerman S (1976) Structural characteristics of cities and the severity of racial disorders. Am Sociol Rev 41(5):771–793

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) (2009) Program populations (1969–1988). National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released November 2009. www.seer.cancer.gov/popdata

Updegrove A, Cooper M, Orrick E, Piquero R (2018) Red states and black lives: applying the racial threat hypothesis to the black lives matter movement. Justice Q 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1516797

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), National Center for Health Statistics (2007) Multiple cause of death, 1959–1988. [Computer file]. ICPSR03895-v2. (Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics [producer], 2001. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Ann Arbor. https://doi.org/10.3886/icpsr03895

Varon JN (1975) A reexamination of the law enforcement assistance administration. Stanford Law Rev 27(5):1303–1324

Wasow O (2018) “Do protest tactics matter? Evidence from the 1960s black insurgency”. Mimeo

Williamson V, Trump K, Einstein K (2018) Black lives matter: evidence that police-caused deaths predict activity. Perspect Polit 16(2):400–415

Reny TT, Newman BJ (n.d.) Protecting the right to discriminate: the second great migration and racial threat in the American west. Am Polit Sci Rev 1–7

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Chris Auld, Martin Farnham, Andrew Goodman-Bacon, Abraham Wickelgren and participants at the Allied Social Science Association, Canadian Network for Economic History, Population Association of America, and American Law and Economics annual meetings for their comments on earlier versions of this work as well as students at the University of Texas Law and Economics Seminar. We also like to thank William J. Collins and Robert Margo for sharing the riot data for the 1964–1971 period. Any errors or omissions are ours alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and Tables 2, 3, 4, 5.

Pre-trend relationship between date of first riot and deaths by legal intervention—evidence of timing. Notes: Regression coefficients and predicted values are from univariate regressions of the dependent variable Δ in non-white deaths due to legal intervention on the year the first racial uprising occurred in a county. The slope in Fig. 4 is − 0.0313 (0.0535)

Estimates of effects of first riot on the population dynamics. Notes: Figures display weighted least-squares estimates obtained from estimating by Eq. 1. All panels display estimates from model 1 which includes county, C, effects, urban-by-year, U, effects, state-by-year, S, effects and covariates, X, from the 1960 census interacted with a time trend and is plotted with a solid line and circle markers. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered by county are presented by dashed lines and circle markers

Estimates of effects of first riot on the log of violent crime per 100,000 residents. Notes: Figures display weighted least-squares estimates obtained from estimating by Eq. 1. The dependent variable is the log of violent crime per 100,000 residents. Model 1 includes county, C, effects, urban-by-year, U, effects, state-by-year, S, effects and covariates, X, from the 1960 census interacted with a time trend and is plotted with a solid line and circle markers. Model 2 includes county, C, effects, year, Y, effects but reweight observations by propensity scores based on the probability of rioting to reweight non-rioting counties. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered by county are presented by dashed lines and circle markers for model 1 and square markers for model 2. Both models use 1960 population by race as weights and use non-rioting counties as the comparison group

Estimates of effects of first riot on the log of murder per 100,000 residents. Notes: Figures display weighted least-squares estimates obtained from estimating by Eq. 1. The dependent variable is the log of murder per 100,000 residents. Model 1 includes county, C, effects, urban-by-year, U, effects, state-by-year, S, effects and covariates, X, from the 1960 census interacted with a time trend and is plotted with a solid line and circle markers. Model 2 includes county, C, effects, year, Y, effects but reweight observations by propensity scores based on the probability of rioting to reweight non-rioting counties. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered by county are presented by dashed lines and circle markers for model 1 and square markers for model 2. Both models use 1960 population by race as weights and use non rioting counties as the comparison group. To calculate the murder rate, we use a data imputation process similar to Chalfin and McCrary (2018). We impute the following \(f\left( {murder} \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {{ \ln }\left( 2 \right) - 1 + \frac{murder}{2}} \hfill & { if\; murder < 2} \hfill \\ {{ \ln }\left( {murder} \right) } \hfill & {else} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.\)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham, J.P., Gillezeau, R. Don’t Shoot! The Impact of Historical African American Protest on Police Killings of Civilians. J Quant Criminol 37, 1–34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09443-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09443-8

Keywords

- Protests

- Riots

- Uprisings

- Police homicides

- Police violence

- Killings by law enforcement

- Black lives matters

- Civil rights