Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to investigate whether total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients who consulted an occupational medicine specialist (OMS) within 3 months after surgery, return to work (RTW) earlier than patients who did not consult an OMS.

Methods

A multi-center prospective cohort study was performed among working TKA patients, aged 18 to 65 years and intending to RTW. Time to RTW was analyzed using Kaplan Meier and Mann Whitney U (MWU), and multiple linear regression analysis was used to adjust for effect modification and confounding.

Results

One hundred and eighty-two (182) patients were included with a median age of 59 years [IQR 54–62], including 95 women (52%). Patients who consulted an OMS were less often self-employed but did not differ on other patient and work-related characteristics. TKA patients who consulted an OMS returned to work later than those who did not (median 78 versus 62 days, MWU p < 0.01). The effect of consulting an OMS on time to RTW was modified by patients’ expectations in linear regression analysis (p = 0.05). A median decrease in time of 24 days was found in TKA patients with preoperative high expectations not consulting an OMS (p = 0.03), not in patients with low expectations.

Conclusions

Consulting an OMS within 3 months after surgery did not result in a decrease in time to RTW in TKA patients. TKA patients with high expectations did RTW earlier without consulting an OMS. Intervention studies on how OMSs can positively influence a timely RTW, incorporating patients’ preoperative expectations, are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide there is a steep rising demand for total knee arthroplasty (TKA), especially among patients of working age. By 2030–2035 the majority of TKA patients in the US and UK will already be of working age [1,2,3]. Return to work (RTW) rates among these TKA patients vary between 40 and 98% with a mean time to return to work between 8 and 17 weeks [4, 5]. Time to RTW in TKA patients is often retrospectively measured and therefore prone to recall bias [5]. In the most recent prospective cohort study in the Netherlands only 24% of TKA patients returned to work completely at 3 months, which was 51% at 6 and 71% at 12 months [6]. These percentages are in contrast with orthopedic guidelines advising RTW within 3 months, starting gradually if needed [7]. Moreover patients who receive TKA have the greatest productivity and income loss when compared to other types of common surgery [8].

To decrease time to RTW among these TKA patients, attention should be paid to the beneficial and hindering factors for RTW within health care as well as occupational health. Known prognostic factors effecting RTW are patient characteristics, such as age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI) and physical function score, as well as work-related characteristics, such as sense of urgency to RTW, having a handicap accessible workplace, preoperative sick leave, and having knee-straining work [4, 5]. Active referral by the orthopedic surgeon to an occupational health expert is expected to enhance RTW [9,10,11,12].

The occupational health experts in the Netherlands are the Occupational Medicine Specialists (OMS) who are physicians with four years post-graduate training in Occupational Medicine. Every employee has direct access to an OMS, on account of the employer. Self-employed patients can consult an OMS on their own account, though this consultation is not familiar to patients and health care professionals and thereby not frequently used.

By their specialized training the OMS has insight into the patient’s work demands in relation to the patient’s work ability. Subsequently the OMS can advise and support the RTW process, for instance by advising adjustment of working hours, working tasks (modified duties) or workplace adaptations using ergonomic principles. Patients who have limited access to these kinds of work adjustments and have difficulty performing work-related knee-straining activities may also be referred by their OMS to work rehabilitation [13]. Moreover, an OMS is able to discuss and stimulate the sense of urgency to RTW given the value of work in life [14]. Currently however, no evidence is available on whether time to RTW after TKA can be decreased by consulting an OMS. The aim of this study is to investigate whether TKA patients who consult an OMS within 3 months after surgery, return to work sooner than patients who do not consult an OMS.

Methods

Study Design and Population

A multi-center prospective cohort study among TKA patients was performed [12]. Patients were included from nine surgeons, working in seven hospitals, in five Dutch regions, to minimize selection bias. The hospitals varied from general hospitals, large teaching hospitals to tertiary university hospitals. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients undergoing TKA between June 2014 and March 2018, (2) aged 18 to 65 years (working age), (3) having a paid job, (4) self-reported intend to RTW after surgery and (5) provided information about consulting an OMS within 3 months after TKA or not. Data were collected before TKA and at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery using a self-report questionnaire in Dutch. Patients could choose a paper or electronic version of the questionnaire to avoid selection bias based on patients’ computer literacy. At each measurement, non-responding patients were reminded up to two times after 2 weeks. Patients who were willing to participate but missed the preoperative measurement due to logistical reasons, were included in the follow-up measurements.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics were registered, such as date of birth, gender, body height and body mass. The latter two were used to calculate BMI. Patients were asked whether they had other diseases that were limiting their activities at work, with three categories: (1) No, (2) Yes, one disease that is limiting my activities at work, and (3) Yes, more than one disease that is limiting my activities at work. These categories were dichotomized into either ‘no’ (No) or ‘one or more other disease(s) that limits my activities at work’ (Yes), which was defined as comorbidity. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) subscales on pain, symptoms and quality of live were filled out by the patients. All KOOS subscales are validated in Dutch and range from 0, representing extreme knee problems, to 100 representing no knee problems [15]. The Work Osteoarthritis or joint-Replacement Questionnaire (WORQ) was used for the work-related physical functioning score, and is also validated in Dutch [16]. The WORQ score consists of 13 items on work-related knee-straining activities, such as lifting and working with hands below knee-height. These 13 activities are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (extreme difficulty or unable to perform) to 4 (no difficulty at all), resulting in a converted total score between 0 (extreme difficulties) to 100 (no problems at all).

Work-Related Characteristics

Work-related characteristics were also self-reported: being a bread winner (yes/no); being self-employed (yes/no); having a handicap accessible workplace (yes/no); and preoperative sick leave (yes/no). Patients’ preoperative expectation regarding work ability at 6 months after surgery was reported by using the single item work ability score (WAS). This score ranges from 0, at which score a patient expect no work ability at all at 6 months postoperative, to 10, an expected work ability as it was at lifetime best [17, 18]. Expected WAS was dichotomized with a cut-off point of 8 or higher defined as high expectations of postoperative work ability and lower than 8 as low expectations of postoperative work ability [17]. Having a knee-straining job was defined by patients who reported that they have to perform at least one of the following five activities ‘often’ or ‘always’: crouching, kneeling, clambering, taking the stairs or lifting [19, 20]. Resumed working hours at 6 and 12 months after surgery were self-reported and calculated as a percentage of self-reported regular working hours of each individual TKA patient. TKA patients reported their actual work ability on the single item Work Ability Score (WAS) again at 6 and 12 months. Furthermore, satisfaction with their physical work ability regarding the operated knee was reported on a single item score from 0, not satisfied at all to 10, totally satisfied.

Occupational Medicine Specialist

Whether or not an OMS was consulted by TKA patients within 3 months after surgery was self-reported at the 3-month postoperative measurement.

Potential Confounders for RTW

Potential confounders for RTW were: age; gender; BMI; pain related to the knee (KOOS pain); symptoms related to the knee (KOOS symptoms); quality of life related to the knee (KOOS quality of life); perceived difficulty with work-related knee-straining activities (WORQ score); having a knee-straining job; preoperative sick leave; being self-employed; availability of a handicap accessible workplace and preoperative expected work ability (expected WAS) at 6 months postoperative [4, 5].

Study Size

A study size of 160 patients was deemed to be needed. This was based on an expected inclusion of six dichotomous or continuous variables in multiple linear regression analyses. Thereby we took into account that for every variable in the multiple analyses a minimum of 10 patients are required [21]. Finally, we assumed that 60 patients would be included without consult of an OMS and 100 patients with consult of an OMS after TKA.

Statistics

Firstly, descriptive statistics were used to describe patient and work-related characteristics of TKA patients who did and did not consult an OMS. Differences between these groups were statistically tested at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Secondly, a Mann Whitney U non-parametric test (MWU) and a Kaplan Meier survival analysis were performed. The Kaplan Meier survival analysis was performed with the Wilcoxon (Breslow) test to give more weight to the first phase of RTW. This was done because of the importance of an early RTW and in line with the Dutch orthopedic guideline recommendation of RTW within 3 months.

Thirdly, to answer the question of whether or not consulting an OMS decreases (median) time to RTW after TKA, multiple linear regression analysis was performed in order to adjust for confounding and effect modification. To meet the assumptions of linear regression, the outcome measure, time to RTW, was transformed by taking the square root. Potential confounders were included in the multiple linear regression analysis that correlated with time to RTW at a significance level of p = 0.05 and showed a collinearity of < 0.7 using Spearman's Rank correlation coefficient with other potential confounders. This linear regression analysis was performed using the comprehensive method for association models [21]. First, OMS consultation was entered into the model. Initially, effect modifiers were identified because this meant that the presence of this factor differently affected (the square root of) time to RTW, if an OMS was consulted or not. A significance level of p < 0.10 was used to prevent potential relevant effect modifiers from being opted out. If effect modification was observed, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed within each stratum of the effect modifier to secure that the effect on RTW could be attributed to this specific factor. Subsequently, a confounder analysis was performed by adding one potential confounder at the time to the regression model, if needed per stratum of the effect modifier. The predictor variable with the largest effect on the regression coefficient of the OMS, and with an effect of at least a 10% change in the coefficient of the OMS, was then added to the model. These steps were repeated until none of the remaining potential confounders had an effect of at least a 10% change on the coefficient of the OMS, the number of cases was less than ten per variable or if no variables were left. Assumptions for applying linear regression analysis were checked on the final association model for homoscedasticity of errors, independency of errors using the Durbin-Watson test and normal distribution of errors.

Additionally, as a secondary outcome, working hours, experienced WAS and satisfaction with work ability at 6 and 12 months was assessed for differences between patients who did and did not consult an OMS.

All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient and Work-Related Characteristics

One hundred eighty-two (182) TKA patients were included (Fig. 1) with a median age at 3 months postoperative of 59 years [IQR 54–62], 87 men (48%), a median BMI of 29 [IQR 26–32], and a median KOOS symptoms score of 61 [IQR 46–71] (Table 1). Patients with and without an OMS consult did not differ regarding their personal and work-related characteristics such as comorbidity, KOOS symptoms and preoperative sick leave, except for being self-employed. Patients who consulted an OMS were less often self-employed (2%) than those not consulting an OMS (30%, p < 0.01). Preoperative KOOS subscales and WORQ scores were also not statistically different between TKA patients who did and did not consult an OMS.

OMS Consultation and Effect on Time to Return to Work

The Kaplan Meier survival curve of patients consulting an OMS (thick solid line) shows a later RTW compared to patients without consult of an OMS (dashed line) within 3 months postoperative (n = 182, p = 0.03 Fig. 2).

Kaplan Meier survival curves of time to RTW (calendar days) among TKA patients with (thick solid line) and without (dashed line) a consult of an occupational medicine specialist within 3 months postoperative (n = 182) differ, p = 0.03 (RTW return to work, TKA total knee arthroplasty, OMS occupational medicine specialist)

Patients, regardless whether or not they visited an OMS within 3 months postoperative, returned to work with a median of 72 days [IQR 47–108]. Patients who consulted an OMS returned to work later (median 78 [61–111]) than patients who did not consult an OMS (median 62 [34–102], MWU p < 0.01; Table 2).

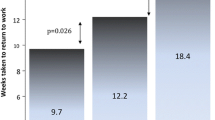

The effect of consulting an OMS on time to RTW within 3 months postoperatively was modified by two variables in linear regression analysis, namely expected WAS (p = 0.054) and being self-employed (p = 0.062). Therefore, confounder analysis was performed in patients with high and low expected WAS and in patients with paid employment and being self-employed (Table 2). After controlling for confounding the following results were found. Only among patients who expected good postoperative work ability a significant association was found between the (square root of) days to RTW and a consult with an OMS when adjusted for having a knee- straining job and their KOOS pain level at 3 months postoperative (√days to RTW = √(7.875 + (1.404*OMS) + (2.524*Knee-straining job) + (− 0.027*KOOS-pain))). This association resulted in an R square of 0.274, meaning 27% of (the variation in) time needed to RTW was explained by (the variation in) a consult with an OMS, a knee straining job and pain level. TKA patients with high expected WAS returned to work 24 days later when an OMS was consulted compared to patients who did not consult an OMS (p = 0.03). TKA patients with low expected WAS returned to work at the same time whether an OMS was consulted or not (p = 0.69). TKA patients with paid employment returned to work at the same time with or without consulting an OMS (p = 0.14). Patients being self-employed seemed to return to work later when an OMS was consulted, however due to the low number of these patients (n = 2) this analysis could not be performed. Therefore, it could not be confirmed that employment was an effect modifier or confounder.

Working Hours and Work Ability

In patients with high expected WAS without consulting an OMS the number of working hours (median 32 [18–40]), experienced WAS (median 8 [IQR 7–8] and satisfaction with work ability (median 8 [IQR7-9]) at 6 months postoperative did not differ from patients with high expected WAS consulting an OMS (respectively 32 [IQR 16–40], 7 [IQR 7–8] and 8 [IQR 7–8]). The same was true at 12 months postoperative.

Preoperative Non-responders

Patients who did not respond to preoperative measurements did not differ significantly (at a p < 0.05 significance level) from patients who responded to preoperative measurements regarding patient and work-related characteristics (Supplementary data, Table 3).

Discussion

Consulting an OMS did not show an earlier RTW among TKA patients. Moreover, in the group of TKA patients with high expectations an earlier RTW was seen in patients that had not consulted an OMS.

Regarding no earlier RTW in patients who consulted an OMS, four possible explanations can be given. First, it might be that OMSs advise a more conservative RTW trajectory than needed, to secure a safe recovery and sustainable RTW without increasing a risk of complications. At the moment no occupational health guideline regarding RTW advice for these patients is available in the Netherlands and other countries. The only guidance given is the practice-based recommendation in Dutch orthopedic TKA guideline stating that ‘RTW is possible within 3 months and should start gradually if needed [7]. Also the recently published Dutch and American physiotherapy guidelines, advice early and personalized progression of physical activity for TKA patients but lack recommendations regarding return to work [22, 23]. Recently the Dutch multidisciplinary practice guideline for occupational health professionals was developed for patients with low back pain and lumbosacral radicular syndrome [24]. Following this example a multidisciplinary occupational health guideline on prevention and work participation of knee osteoarthritis patients, as well as pre- and postoperative care in TKA patients can be of help for informed decision making and alleviate the burden of knee OA and TKA on patients, employers, health care and society [3, 8].

A second explanation might be that the timing of the consult with an OMS is not early enough to establish a decrease in time to RTW. In the Netherlands not every patient, for instance a self-employed patient, has free access to an OMS. If an employed patient can consult an OMS the waiting time for an appointment is often around 6 weeks which is when a consultation is mandatory to comply with the Dutch Gatekeeper law. This law states that a problem analysis regarding RTW has to be made by an OMS within the first 6 weeks of sick leave and this analysis should be used to make an RTW-plan by the employer and employee in the first 8 weeks of sick leave. However, managing the RTW-process for TKA patients should start earlier and preferably before surgery to have an effect on timely RTW after TKA. This is especially the case if hindering factors need to be managed like perceived difficulty with knee-straining activities, having a knee-straining job or a workplace that is not handicap accessible.

A third explanation might be that the previously mentioned waiting time for an OMS appointment can potentially lead to a wait-and-see attitude regarding RTW in patients who do not prefer or feel secure to RTW on their own accord. This would possibly be true in patients with less self-management skills, less confidence in their TKA recovery, less urgency to return to work or other reasons for a wait-and-see attitude regarding RTW. This possible wait-and-see attitude caused by the time to an OMS appointment is therefore also related to the fourth possible explanation, namely a possible selection bias.

This fourth possible explanation for no decrease in time to RTW among patients who consult an OMS might be selection bias based on psychosocial factors we did not measure, or so called reverse causation. In terms of the biopsychosocial model this study does not confirm selection bias based on biological factors, such as comorbidity, knee pain and symptoms (KOOS) or difficulty to perform work-related knee-straining activities (WORQ). However, selection bias based on psychosocial factors could be addressed more properly. To limit the number of questions, we prioritized prognostic variables for RTW regarding TKA patients described in literature. Remarkably, self-efficacy was not one of these variables. Patients that have less possibilities for personal job development or have less work recognition are recently found to have an increased time to RTW after TKA [25]. It seems plausible that these characteristics would be more present among patients consulting an OMS because of a possible need for psychosocial support.

Patients Who Expect Good Postoperative Work Ability

A mixture of the aforementioned reasons 1, 2 and 3 can probably explain the later RTW in patients with high expected WAS that consulted an OMS compared to patients that did not consult an OMS. Regarding a probably conservative RTW trajectory by OMSs to secure a safe recovery and sustainable RTW, we could assess in our data that the early RTW in patients without consulting an OMS did not result in a worse outcome. The number of hours at work, the work ability of patients and the satisfaction with work ability did not differ between patients who did and did not consult an OMS.

Another explanation of an earlier RTW in patients with high expected WAS that did not consult an OMS might be a high self-efficacy which increases the probability of RTW on their own accord instead of waiting for an appointment with an OMS. Patients with high expected WAS are probably also patients with more possibilities for personal job development or more work recognition [8]. Moreover, expectations of work ability after surgery might (partly) be based on realistic insights in their physical ability in relation to physical job demands by these patients. If that is true then it can be argued that patients with high expected WAS would be able to safely RTW early and on their own accord in contrast to patients with low expected WAS given their worse physical ability in relation to their physical job demands. Qualitative findings also support the hypothesis that patients’ needs are partially based on having access to work adjustments and tools [13]. In line with these findings, patients in our study who have high expectations and do consult an OMS, might probably experience a lack of supportive interventions and for that reason consult an OMS.

Future Directions

First of all, we would recommend to better inform OMSs regarding facilitating and hindering factors for RTW and corresponding median times for RTW regardless whether this is partial or full. This information might empower OMSs and thereby they can reassure their patients that resuming work in a timely manner has better prognosis for RTW [26]. As yet we do not know which exercise-based therapy and integrated care interventions are effective for soon, safe and sustainable RTW in TKA patients [27, 28]. Moreover, in line with the hierarchy of risk management it is more ethical to start with adjusting the work to the patient’s needs, especially if the work is knee-straining. Recent studies have shown that interventions supporting RTW in arthroplasty patients based on knowledge for safe recovery, also regarding work-related activities, and sustainable RTW are being developed [11, 29, 30]. Managing too high patient expectations has also been suggested in TKA patients for better patient-reported outcome as well as RTW [12, 31, 32]. The present study provides another perspective on the relevance of patients’ expectations, given that patients with high expectations who do not consult an OMS have a more timely RTW than their counterparts who consulted an OMS. OMSs might also pay attention to other patient needs than addressed by the potential confounders in our study because these only explained 24% of the later RTW in patients with high work ability expectations.

Independent of what advice or guidance supports an earlier RTW, it is also important to know whether this earlier RTW can be considered safe recovery and sustainable RTW. As said, TKA patients with high expectations without consulting an OMS returned to work earlier and had the same outcome of work ability at 6 and 12 months as their counterparts. We foresee, based on these findings, that an earlier RTW seems safe and sustainable, especially when patients have a high physical ability given their physical job demands and return to work on their own accord. Of course, more prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Promising Interventions

Hindering factors for RTW need to be addressed. Based on earlier research potential effective interventions might be work-directed rehabilitation in patients with a knee-straining job, facilitating arrangements to improve access to the workplace, preoperatively managing patient expectations regarding work ability after TKA and introducing ergonomic measures to decrease the physical workload [33, 34]. These measures could be initiated or coordinated by an OMS, even before surgery, so that the proposed interventions could be implemented in time [3, 35, 36]. Moreover, patients receiving a positive advice regarding RTW by their OMS as well as their orthopedic surgeon said that this was beneficial for their RTW [37]. When the orthopedic surgeon refers patients with hindering factors for RTW to their OMS, preferably before surgery, this might enhance a timely RTW if the OMS is able to act accordingly. RTW advise probably should also be individualized and needs involvement of the employer, as has been found in an intervention mapping approach to develop a clinical occupational advice intervention for knee arthroplasty patients [11, 38]. M/-eHealth could be another promising add-on intervention, since it can provide personalized and frequent advice for TKA patients regarding timely performance of activities based on for instance activity trackers, self-reported recovery and algorithms [29, 34]. Another possible effective element might be setting specific work activity goals in rehabilitation, since this resulted in an increased satisfaction with performing work-related activities in TKA patients [39]. Physiotherapists, especially those specialized in occupational health and ergonomics, could also add value because of their knowledge of the physical recovery of the patient and of assessing and (temporarily) adjusting physical job demands [33]. This dual approach of work directed care and corresponding adjustment of job demands might have potential to enhance (time to) RTW. Above all, given the lack of evidence, studies are needed that evaluate the effectiveness of physical rehabilitation for RTW, given that this care is received by most patients post-surgery [27].

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is its prospective multicenter design, in which seven hospitals throughout the Netherlands participated, resulting in a large number of working age TKA patients intending to RTW (n = 182). Another strength is that, as far as we know, this is the first study addressing the potential added value of consulting an OMS regarding RTW after TKA. Moreover, this study incorporated a priori chosen potential confounders for RTW although other confounders might still be present. And lastly, our multiple linear regression analysis, also focusing on modifiers and confounders of the effect of an OMS consult on RTW, can also be considered a strength of this study.

The most important limitation of our study is that selection bias is still possible due to the study design, being a prospective cohort study and not an intervention study. Another major limitation of our study is that we only had self-reported data and did not have information regarding the content and exact timing of the OMS consult. Also, the RTW process is complex and can be influenced by factors not measured, e.g. psychosocial factors such as support from a patients supervisor or colleagues at work [5]. Another limitation of the study is that it was originally designed as a cross-sectional preoperative measurement and pending approval for the postoperative measurements by the Medical Ethics Review Committee, the first consecutively 49 patients could not be invited for their 3-months measurement. Therefore, these patients were not eligible but we expect these to be random and not subject to whether or not an OMS was consulted within 3 months.

Conclusion

Consulting an OMS within 3 months after surgery did not result in an earlier RTW in TKA patients. TKA patients with preoperative high expectations of work ability did even RTW earlier if they had not consulted an OMS compared to their counterparts. Given the increasing number of working age TKA patients worldwide, these findings strengthen the plea for more research on interventions to decrease time to RTW, incorporating the positive effects of high expectations on RTW.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–5.

Culliford D, Maskell J, Judge A, Cooper C, Prieto-Alhambra D, Arden NK, et al. Future projections of total hip and knee arthroplasty in the UK: results from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(4):594–600.

Kuijer PPF, Burdorf A. Prevention at work needed to curb the worldwide strong increase in knee replacement surgery for working-age osteoarthritis patients. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(5):457–60.

Pahlplatz TM, Schafroth MU, Kuijer P. Patient-related and work-related factors play an important role in return to work after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J ISAKOS. 2017;2:127–32.

Van Leemput D, Neirynck J, Berger P, Vandenneucker H. Return to work after primary total knee arthroplasty under the age of 65 years: a systematic review. J Knee Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722626.

Hylkema TH, Stevens M, van Beveren J, Rijk PC, Brouwer RW, Bulstra SK, et al. Recovery courses of patients who return to work by 3, 6 or 12 months after total knee arthroplasty. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31:627–39.

NOV FMS. Veiligheid hervatten werk na TKP operatie 2014 Richtlijnen database NOV: NOV Federatie Medisch Specialisten; 2014. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/totale_knieprothese_2014/werk_en_sportbelasting_bij_tkp/hervatten_werk_na_tkp_operatie.html. . Accessed 2014

Hah JM, Lee E, Shrestha R, Pirrotta L, Huddleston J, Goodman S, et al. Return to work and productivity loss after surgery: a health economic evaluation. Int J Surg. 2021;95:106100.

Hylkema TH, Brouwer S, Stewart RE, van Beveren J, Rijk PC, Brouwer RW, et al. Two-year recovery courses of physical and mental impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions after total knee arthroplasty among working-age patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;44:291–300.

Pahlplatz TM, Schafroth MU, Krijger C, Hylkema TH, van Dijk CN, Frings-Dresen M, et al. Beneficial and limiting factors in return to work after primary TKA: patients’ perspective. Work. 2020.

Coole C, Baker P, McDaid C, Drummond A. Using intervention mapping to develop an occupational advice intervention to aid return to work following hip and knee replacement in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):523.

van Zaanen Y, van Geenen RCI, Pahlplatz TMJ, Kievit AJ, Hoozemans MJM, Bakker EWP, et al. Three out of ten working patients expect no clinical improvement of their ability to perform work-related knee-demanding activities after total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(3):585–94.

Coutu MF, Gaudreault N, Major ME, Nastasia I, Dumais R, Deshaies A, et al. Return to work following total knee arthroplasty: a multiple case study of stakeholder perspectives. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35(6):920–34.

Abma FI, Brouwer S, de Vries HJ, Arends I, Robroek SJ, Cuijpers MP, et al. The capability set for work: development and validation of a new questionnaire. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(1):34–42.

KOOS. www.KOOS.nu. 2012. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

Kievit AJ, Kuijer PP, Kievit RA, Sierevelt IN, Blankevoort L, Frings-Dresen MH. A reliable, valid and responsive questionnaire to score the impact of knee complaints on work following total knee arthroplasty: the WORQ. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1169–75.

Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Järvisalo S, Koskinen S. Dimension of work ability: results of the Health 2000 Survey. Helsinky: Finnish Centre of Pensions, The Social Insurance Institution, National Public Health Institute, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 2008.

Stienstra M, Edelaar MJA, Fritz B, Reneman MF. Measurement properties of the work ability score in sick-listed workers with chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;32:103–13.

Verbeek J, Mischke C, Robinson R, Ijaz S, Kuijer P, Kievit A, et al. Occupational exposure to knee loading and the risk of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Saf Health Work. 2017;8(2):130–42.

Palmer KT. Occupational activities and osteoarthritis of the knee. Br Med Bull. 2012;102:147–70.

Twisk JWR. Inleiding in de toegepaste biostatistiek. Amsterdam: Reed Business; 2011.

van Doormaal MCM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Peter WF. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskel Care. 2020;18(4):575–95.

Jette DU, Hunter SJ, Burkett L, Langham B, Logerstedt DS, Piuzzi NS, et al. Physical therapist management of total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2020;100(9):1603–31.

Luites JWH, Kuijer P, Hulshof CTJ, Kok R, Langendam MW, Oosterhuis T, et al. The Dutch multidisciplinary occupational health guideline to enhance work participation among low back pain and lumbosacral radicular syndrome patients. J Occup Rehabil. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-09993-4.

Kamp T, Brouwer S, Hylkema TH, van Beveren J, Rijk PC, Brouwer RW, et al. Psychosocial working conditions play an important role in the return-to-work process after total knee and hip arthroplasty. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;32:295–305.

Burdorf A, van der Beek AJ. To RCT or not to RCT: evidence on effectiveness of return-to-work interventions. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(4):257–9.

Kuijer P, van Haeren MM, Daams JG, Frings-Dresen MHW. Better return to work and sports after knee arthroplasty rehabilitation? Occup Med (Lond). 2018;68(9):626–30.

Coenen P, Hulsegge G, Daams JG, van Geenen RC, Kerkhoffs GM, van Tulder MW, et al. Integrated care programmes for sport and work participation, performance of physical activities and quality of life among orthopaedic surgery patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1):e000664.

Straat AC, Coenen P, Smit DJM, Hulsegge G, Bouwsma EVA, Huirne JAF, et al. Development of a personalized m/eHealth algorithm for the resumption of activities of daily life including work and sport after total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a multidisciplinary Delphi study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4952.

Strijbos DO, van der Sluis G, Boymans TAEJ, de Groot S, Klomp S, Kooimjman CM, et al. Implementation of back at work after surgery (BAAS): A feasibility study of an integrated pathway for improved return to work after knee arthroplasty. Musculoskeletal Care. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1633.

Hoorntje A, Leichtenberg CS, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Kerkhoffs G, Nelissen R, et al. Not physical activity, but patient beliefs and expectations are associated with return to work after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):1094–100.

Jain D, Nguyen LL, Bendich I, Nguyen LL, Lewis CG, Huddleston JI, et al. higher patient expectations predict higher patient-reported outcomes, but not satisfaction, in total knee arthroplasty patients: a prospective multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S166–70.

Daley D, Payne LP, Galper J, Cheung A, Deal L, Despres M, et al. Clinical guidance to optimize work participation after injury or illness: the role of physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(8):CPG1–102.

Baker P, Kottam L, Coole C, Drummond A, McDaid C, Rangan A, et al. Development of an occupational advice intervention for patients undergoing elective hip and knee replacement: a Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e036191.

Stigmar K, Dahlberg LE, Zhou C, Jacobson Lidgren H, Petersson IF, Englund M. Sick leave in Sweden before and after total joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis patients. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(2):152–7.

Kaila-Kangas L, Leino-Arjas P, Koskinen A, Takala EP, Oksanen T, Ervasti J, et al. Sickness absence and return to work among employees with knee osteoarthritis with and without total knee arthroplasty: a prospective register linkage study among Finnish public sector employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2021;47:600–8.

Mollema C, Kuijer P. Working on better work-directed care: what do knee prosthesis patients consider facilitating and hindering factors for return to work? [In Dutch: Werken aan betere arbeidsgerichte zorg: wat vinden knieprothesepatiënten bevorderende en belemmerende factoren voor terugkeer naar werk?]. TBV - Tijdschr Bedrijfs- en Verzekeringsgeneeskd 2018;26:473–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12498-018-0288-4.

Nouri F, Coole C, Narayanasamy M, Baker P, Khan S, Drummond A. Managing employees undergoing total hip and knee replacement: experiences of workplace representatives. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):451–61.

Hoorntje A, Waterval-Witjes S, Koenraadt KLM, Kuijer P, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs G, et al. Goal attainment scaling rehabilitation improves satisfaction with work activities for younger working patients after knee arthroplasty: results from the randomized controlled ACTION trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(16):1445–53.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all research assistants for their help in conducting this study. We also sincerely thank all patients who kindly participated in this study; without the information they provided, this study would not have been possible.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YvZ and PK designed and conceived the study. AK, RvG, TP, MH, LB, MS, DH, TV, DD and VS assisted in data collection. YvZ and PK were responsible for the processing and analyses of data. YvZ drafted the first version of the article. MH, AvdB and PK contributed to the further drafting of the article. All authors agreed on conception and design and contributed equally to interpretation of data and critical revision of the paper. YvZ wrote the final draft. PK is guarantor of the article. Final approval of the version for publication was agreed upon by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

AvdB declared receiving grants for scientific research paid to his institution, receiving consulting fees and having a leadership role in scientific boards mostly without payment or paid to his institution. YvZ declared having a leadership role in the International Federation of Physical Therapists working in Occupational Health and Ergonomics, without payment. AK, RvG, TP, MH, LB, MS, DH, TV, DD, VS and PK declared no competing interest.

Ethical Approval

This is an observational study. The AMC Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required (reference number W14_006 # 14.17.0021).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Zaanen, Y., Kievit, A.J., van Geenen, R.C.I. et al. Does Consulting an Occupational Medicine Specialist Decrease Time to Return to Work Among Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients? A 12-Month Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. J Occup Rehabil 33, 267–276 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10068-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10068-1