Abstract

This study analyzes whether subjective well-being can explain the populist vote in the Netherlands. Using data on voting intention and subjective well-being for over 7700 individuals from 2008 to 2019—a period during which populist parties became well-established in the Netherlands—we estimate logit and multinomial logit random effects regressions. We find evidence of an association between decreased subjective well-being and the probability to vote for a populist party that goes beyond changes in dissatisfaction with society—lack of confidence in parliament, democracy and the economy—and ideological orientation. At the same time, we find no evidence for a relationship between subjective well-being and voting for other non-incumbent parties other than populist parties.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Populist ideology is on the rise in the Western world (Caiani & Graziano, 2019; March, 2011; Zaslove, 2008). One can think here of the vote for Trump in the United States (USA), the Brexit campaigns in the United Kingdom, and the rise of radical right- and left-wing parties in many European countries. Populism can be defined as “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’’ (Mudde et al., 2004). Despite the fact that populism act as a remedial to malfunctioning democratic regimes (Levitsky & Loxton, 2012), it is by many seen as a threat to stability because it would transform contemporary democracies into ochlocracies or more authoritarian democracies in which the masses are under the influence of demagogues and the protection of minorities by rule of law is in jeopardy (Hasanović, 2015). In Poland, judicial reforms by the PiS party is threatening judicial independence and the separation of powers (Kovács & Scheppele, 2018), where the erosion of the rule of law seems to harm women and LGBTQ + rights. In Hungary, the Fidesz party of Victor Orbán has been accused of curtailing free speech and freedom of press and depicting immigrants as a threat to inner security (Halmai, 2018). In the United States, Donald Trump initiated the building of a wall between the USA and Mexico and protectionist and anti-globalization economic policies under the flag of “America First’ (Löfflman, 2019).

The surge in populism has led many to wonder what motivates this voting behavior. The rise of populism has generally been associated with dissatisfaction with current democracy, where the electoral process is still democratic but political institutions are believed to be unable to unwilling to fulfill the needs and demands of citizens (Berman, 2019, 2021; Hasanović, 2015). Some studies have focused on other factors explaining voting behavior such as status threat due to unemployment and inequality (Guriev, 2018), globalization and trade competition (Colantone & Stanig, 2018) and the retreat of the welfare state (Kriesi, 1998). Others have attributed the rise of populism in the West not to economic insecurity but to a cultural backlash and a reaction of once-dominant parts of the population to progressive viewpoints about ethnic minorities, women, and the LGBTQ + community (Inglehart & Norris, 2017). At the same time, there also seems to be no consistent profile of populist voters across different countries (Rooduijn, 2018). Populist parties, as well as their drivers of increasing support, can be very heterogeneous (Colantone & Stanig, 2019). Ivarsflaten (2008) even argues that the populist parties in the West do not have anything in common except for their anti-immigration policies.Footnote 1

Despite differences in the underlying reasons for the rise of populism, Ward et al. (2021) argue that political, cultural, economic, and social factors that affect subjective well-being – also known as happiness or life satisfaction (Veenhoven, 2000)—of people predict populist voting. The central argument of Ward et al. (2021) based on the retrospective voter hypothesis (Kramer, 1971; Fiorina, 1978) is intuitive: if one is dissatisfied, this provides a signal that one’s current circumstances should be changed, resulting in a vote for the non-incumbent party. Along these lines, voters punish the incumbent parties in a democracy if their experienced welfare worsens as they blame the incumbent party for this deterioration.

The populist vote can be perceived as a special case of the non-incumbent vote, where citizens feel unrepresented by the ruling elite (incumbent parties and traditional opposition parties) and would like radical change in the political system because they lost in the current one. Nai (2021) argues in this regard that the often emotional and negative tone of populist leadersFootnote 2 speaks particularly to those citizens who feel less happy and hold the political system (partly) accountable for this. Hence, the populist vote goes beyond mere dissatisfaction with society and is also associated with voters’ (personal) subjective well-being, where unhappiness, grievances and frustrations can turn into populist support when voters feel unheard. Several empirical papers have now found an association between decreases in subjective well-being and populist voting in Europe and North America (Algan et al., 2018; Nowakowski, 2021; Ward et al., 2021), although it remains unclear to what extent dissatisfaction with society rather than dissatisfaction with personal circumstances drives populist support (Giebler et al., 2021; Burger et al., 2022).

The study presented here examines the relation between subjective well-being and populist voting in the Netherlands, a country with a multi-party system that experienced a strong surge of populism in the 2000s (Schumacher & Rooduijn, 2013). In the period under study (2008–2019), the right-wing Partij voor de Vrijheid (Freedom Party) and Forum voor Democratie (Forum for Democracy) and the left-wing Socialistische Partij (Socialist Party) were the largest populist parties in this country, typically accounting for 20–25% of the popular vote.Footnote 3 In this light, several studies have examined the reasons why people support Dutch populist parties. Van der Waal and De Koster (2018) find that protectionism and political distrust is associated with support for both left-wing and right-wing populist parties. At the same time economic egalitarianism predicts the intention to vote for left-wing populists, while ethnocentrism predicts the intention right-wing populism support. In this regard, Savelkoul and Scheepers (2017) found that lower educated people are more likely to cast their vote for Geert Wilders’ freedom party because of higher levels of perceived ethnic threat, anti-Muslim attitudes and authoritarianism. Other studies have looked at spatial differences in populist voting in The Netherlands. Ouweneel and Veenhoven (2016) attribute populist voting in the city of Rotterdam to personal vulnerability in terms of education, income and health. Van Wijk et al. (2020) find a disproportionate degree of right-wing voting by native populations living in neighborhoods a large share of migrants or in neighborhoods that are surrounded by neighborhoods hosting many migrants. Tubadji et al. (2023) also find that citizens in Dutch municipalities with lower cultural expenditures and a relative decline of the Dutch population have a higher propensity to vote for populist right-wing parties.

The vote for populist parties can also be understood as a form of political protest. Schumacher and Rooduijn (2013) find that both protest attitudes—measured by discontent with politicians in general—and evaluations of party leaders are associated with support for populist parties in the Netherlands. In a panel study of Swiss households, Lindholm (2020) finds that low subjective well-being encourages intentions to engage in political protest in the form of boycott, striking or demonstrating (see also Witte et al., 2020). The same may apply to protest voting for populist parties in the Netherlands.

This study aims to contribute to the existing literature in several ways. First, using voting preferences data over a period of 12 years, this is one of the first studies that examines the effect of subjective well-being on populist voting behavior using panel data.Footnote 4 By utilizing panel data methods, we can account for many individual characteristics that potentially confound the relationship between subjective well-being and populist voting. Utilizing fixed effects models, we show that the relationship between subjective well-being and voting behavior goes beyond dissatisfaction with society. Second, because we are examining subjective well-being and voting behavior in a multiparty system with a low electoral threshold, we are also better able to distinguish the non-incumbent vote from the populist vote.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data and methodology. Section 3 presents the empirical results. Concluding remarks follow in Sect. 4.

2 Context, Data and Methodology

2.1 Context

In the Netherlands, there is a multi-party system where a single party has never won the majority of votes. Therefore, several parties need to work together to form a coalition government. Although the Netherlands has a bicameral system, there are only direct national elections for the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer),Footnote 5 which is comprised of 150 members who are elected for a period of four years. In case of a dissolution of the House of Representatives, new elections take place. The candidates for the House of Representatives are selected from party lists through a proportional representation system based on the total number of valid votes. The minimum threshold for a party to participate is 1/150th of the total valid votes.

In the Dutch House of Representatives, the number of parties has fluctuated between 7 and 18 since 1946. However, populist parties were only marginally represented in the Dutch political landscape until the 2000s. Before this period, the Dutch system can be best described as pillarized, where voters were closely connected with political elites through networks of ideological organization (e.g., church or labor unions). However, Dutch society gradually depillarized and voters became less loyal to political parties (Lucardie, 2008). This process was accelerated by the decrease in ideological distances between political parties (Volkens & Klingemann, 2002) and the disappearance of ties between political parties and media outlets (mainly through the introduction of commercial TV) in the 1990s (Lucardie, 2008). This opened opportunities for new populist parties on both side of the left and right side of the political spectrum (Thomassen, 2000), which also profited from discontent within society and voters that did not feel represented anymore by the traditional parties. In particular, voters felt that the traditional incumbent parties did not listen to their voter base and had neglected issues important to them such as immigration concerns, street crime, teacher shortages, and hospital waiting lists (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2003). This discontent started the rise of the populist movement in the Netherlands and the establishment of political parties such as the Socialist Party, Pim Fortuyn List, Party for Freedom, and Forum for Democracy. In the period under study (2008–2019), particularly the Socialist Party and Party for Freedom were large populist parties.

2.2 Data

To examine the relationship between subjective well-being and voting behavior, we used the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS) panel for the years 2008–2019. In the LISS survey, individuals report on several aspects of their life, including their political preferences, satisfaction with society and how satisfied they are with their lives. Our baseline sample for the logit estimations included 7,717 unique adult respondents who answered the question on political voting intention at least once and who on average filled out all relevant questions in 3.7 (out of 11) waves.Footnote 6 Although 57% of the respondents filled out the survey 3 times or less, almost 15% filled out the survey 8 times or more. Please note, however, that in the LISS panel not every respondent fills out every questionnaire every year. Moreover, Knoef and De Vos (2009) have shown that the LISS panel is generally representative of the Dutch adult population (individuals that are dropped out are replaced by people like them). Also when we compare the stated voting behavior with regard to the elections of 2012 with the results of the 2012 election (see Table 1), we can see that the LISS sample voted quite similarly compared to the general population and deviations are within an acceptable range.

2.3 Classifying Political Parties

We capture voting intention based on the following question: “If parliamentary elections were held today, for which party would you vote?”, where we distinguish initially between two different outcomes: (1) intention to vote on a right-wing or left-wing populist party or (2) intention to vote on another party or to abstain from voting (including blank votes). In a subsequent analysis, we further distinguish between (1) intention to vote on one of the right-wing populist parties, (2) intention to vote on the left-wing populist party, (3) intention to vote on one of the incumbent parties, (4) intention to vote on one of the other non-incumbent parties, and (5) intention not to vote or to vote blank if elections were held today.

To classify right-wing and left-wing populist parties, we follow the PopuList 2.0 classification by Rooduijn et al. (2019), who base their classification on the definition of populism provided by Mudde et al. (2004). A detailed classification of parties can be found in Appendix A. In this taxonomy, political parties are classified by experts as ‘populist’ when they endorse the set of ideas that society is ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people (Rooduijn et al., 2019).Footnote 7 Where the list of Rooduijn et al. (2019) only focuses on populist parties that received at least 2% of the popular vote, we also added smaller (mostly split-offs) populist parties that participated in elections.Footnote 8 In the PopuList 2.0 taxonomy, most political parties can be clearly classified as being populist or not in that experts agree about their status. In the case of the Netherlands, only the classification of the Socialist Party (the only left-wing populist party) was ambiguous in that experts held different opinions whether it should be classified as populist or not. In our study, we therefore distinguish between the left-wing and right-wing parties and consider the Socialist Party a borderline case of a populist party.

2.4 Measuring Subjective Well-being

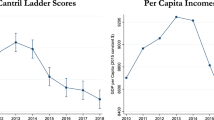

According to Veenhoven (2009), people can use two sources of information when evaluating their own subjective well-being: their emotions and their thoughts. People can evaluate how they are feeling most of the time but can also compare their current life to the best and worst life they can imagine. To this end, we use a subjective well-being index based on three questions. First, we include a more 11-point scale general subjective well-being measure asking: “How satisfied are you with the life you lead at the moment? 0 being equal to ‘not satisfied at all’ and 10 being equal to ‘completely satisfied”, which has been commonly utilized in the economics of subjective well-being literature (Veenhoven, 2009). Second, we use questions provided in the LISS data that capture more explicitly the emotional and cognitive components of subjective well-being. The more emotional assessment is captured using a 11-point scale of happiness in response to the question, which provides a more emotional assessment: “On the whole, how happy would you say you are? 0 being equal to ‘totally unhappy’ and 10 being equal to ‘totally happy’”. The more cognitive component is captured using the 11-point Cantril-ladder (Cantril, 1965) question: “Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?”. Cronbach’s alpha (0.85) indicated that the subjective well-being index comprised of these three variables is internally consistent. Yet, in an additional analysis, we examine the effect of the individual subjective well-being components on voting intention.

2.5 Control Variables

In our analysis, we included several (exogenous) control variables that could confound the relationship between happiness and voting intention, including gender, age, marital status, number of children, level of education, and location of residence. In addition, we include dummy variables indicating the government term in which survey was held. During the period under study (2008–2019), there were four different governments: Balkenende IV (CDA, PvdA, CU), Rutte I (VVD and CDA), Rutte II (VVD and PvdA), and Rutte III (VVD, CDA, D66 and CU),Footnote 9 which can be classified as centre to centre-right governments. Please note that none of the populist parties have been incumbent for the period under study.Footnote 10 Appendix B provides an overview of all variables included in our baseline analyses, while Appendix C provides descriptive statistics.

2.6 Estimation Strategy

In line with the broader literature on voting behavior in multiparty elections (e.g., Whitten & Palmer, 1996), we analyze the relationship between subjective well-being and voting behavior using logit and multinomial logit random effects model. In the random effects logit model – which we use as baseline model—we use a dummy variable that takes the value one if the respondent has the intention to vote on a right-wing or left-wing populist party. In the random effects multinomial model a dependent variable with five outcome categories: (1) intention to vote on one of the right-wing populist parties, (2) intention to vote on the left-wing populist party, (3) intention to vote on one of the incumbent parties, (4) intention to vote on one of the other non-incumbent parties, and (5) intention not to vote or to vote blank if elections were held today. We use intention to vote on one of the other non-incumbent parties as baseline category.

Our baseline regressions that will be presented in Tables 2 and 3 give us an answer to the question whether lower subjective well-being increases the intention to vote for populist parties. In robustness checks, we further explore whether this finding is robust to political orientation and dissatisfaction with society variables. The findings presented in Table 4 help us to better understand whether the subjective well-being effect is driven by dissatisfaction with personal circumstances or by dissatisfaction with politics and society. The variables added to Table 4 also help to overcome potential omitted variable bias. To further account for this problem, we present fixed effect estimations in Table 5 and 6. We address another source of endogeneity in Table 7, where we examine to what extent our results are subject to reverse causality problems.

3 Empirical Results

In this study, we are primarily interested in testing the hypothesis that subjective well-being is associated with the intention to vote for a right-wing or left-wing populist party (on average, 25% of the respondents for a populist party in the period under study). Table 2 presents the baseline estimates of the logit random effects estimations, where the coefficient table shows the odds ratios. In line with earlier work by Nowakowski (2021) on support for populist parties in Europe, we find that female, higher-educated and younger people have a significant lower intention to vote for populist parties. The finding that married people are more likely to vote than people who have never married can be explained that married people are bearers of more traditional values that may feel alienated by more liberal policies (Inglehart & Norris, 2017). Turning to our main variable of interest, we see that if the subjective well-being increases by 1 point, the odds to vote a right-wing or left-wing populist party (versus voting on the incumbent party) decrease by 20%. Replacing the subjective well-being index by the different subcomponents of the index (Table 2; Columns 2–4) yield similar results, although the effect is slightly less pronounced.

At the same time, the subjective well-being may provide a more accurate assessment of an individual’s subjective well-being, incorporating both cognitive and emotional assessment. Because the three measures perform similarly, we will use the combined subjective well-being index, we decided to use the subjective well-being index.

3.1 Subjective Well-Being Associated with Both Left-Wing and Right-Wing Populist Voting

Table 3 presents the estimates of the multinomial logit random effects estimations, where the coefficient table shows the relative risk ratios. If subjective well-being increases by 1 point, the relative risk to vote a right-wing populist and left-wing populist party (versus voting on another non-incumbent party) decrease by 19% and 24% respectively. Re-estimating the model using incumbent party as baseline category shows that an increase in subjective well-being decreases the intention to vote on a populist party vis-à-vis an incumbent party. Decreased subjective well-being is also associated with the propensity to abstain from voting in that a 1-point increase in subjective well-being increases the odds to not vote (versus voting on the incumbent party) by 21%. At the same time, we do not find a significant effect of an increase in subjective well-being on the odds to vote for the incumbent party (vis-à-vis another party). These findings signify that – at least for the Netherlands – lower subjective well-being is associated with voting for populist non-incumbent parties, but not non-populist non-incumbent parties.

3.2 Voting not Only Associated with Dissatisfaction in Society but also with Dissatisfaction with Other Domains in Life

It is interesting to know whether the effect of unhappiness on populist voting behavior is solely driven by dissatisfaction with own circumstances or dissatisfaction with society at large. For this reason, we include several political control variables related to confidence in democracy and parliament, confidence in economy, and political (ideological) orientation in our robustness checks. Confidence in democracy, political parties, and the economy were answered on a 11-point scale (0 = No confidence at all; 10 = Full confidence) – see also Appendix B.

Following Aarts and Thomassen (2008), we include control variables related to three value orientations or policy motivations that define the Dutch electorate: socio-economic left–right dimension, socio-cultural libertarianism/authoritarianism dimension and the religious dimension. Following the theory of Downs (1957), sharing a common set of values (which are supposed to be relatively stable within voters over time) serves as a health base for stable relations between political parties and voters and, hence, stable voting behavior over time. As pointed out by the Aarts and Thomassen (2008), the original pillarized Dutch party system was characterized by a left–right and secular-religious dimension, where each political party could count on a loyal voter base that identified with their specific value orientations. As pointed out by Aarts and Thomassen, the socio-cultural libertarianism/authoritarianism dimension became more important in the early 2000s, when a large coalition of Dutch political parties had settled on some ethical issues and populist were able to make cultural issues the new battleground as these issues were traditionally ignored by the political elite, but highly important to the electorate Pellikaan et al. (2007). In this study, the socio-economic left–right orientation was surveyed using the question: “In politics, a distinction is often made between "the left" and "the right". Where would you place yourself on the scale below, where 0 means left and 10 means right?. The socio-cultural libertarianism/authoritarianism is measured by two opinion questions on anti-immigration and anti-European sentiment using a 5-point Likert scale (see Appendix B). Finally, the religiosity dimension was captured by a question on euthanasia and measured on a 5-point scale as well. Although we realize that these questions only capture part of the value orientations, we are here limited by the availability of data in the LISS.

When we estimate a model in which we add political controls for confidence in institutions and the economy and political orientations (Table 4), our main results hold, although the association between subjective well-being and populist voting behavior (vis-à-vis incumbent voting) becomes less pronounced. This can be explained by the fact that confidence in institutions (related to dissatisfaction with society) affect overall subjective well-being (Bjørnskov, 2008; Arampatzi et al., 2019), but only to a limited extent.

At the same time, lack of confidence in democracy and parliament and political orientation are good predictors of voting populist parties. Specifically, as 1-point increase in confidence in parliament and democracy (on a 5-point scale) decreases the odds to vote on a right-wing or left-wing populist party by 27% and 11% respectively (vis-à-vis one of the other parties or non-voting). In addition, changes in the left–right orientation and specific political orientations are strong predictors of voting on a populist party. We do not find an association between confidence in the economy and intention to vote for a populist party. Respondents that intend to vote on a populist party are not only likely to be more anti-European and anti-immigration, but are also more likely to be pro-redistribution of income and non-religious. These findings are not surprising. First, although the right-wing Freedom Party of Geert Wilders is well-known to be an anti-immigration and anti-Islam party, it also presents itself as a party with a left-wing economic agenda (although it can be questioned it really has). Second, religious people are more likely to vote for one of the Christian political partis in the Netherlands. The significant coefficient for left–right orientation signifies that most populist voters in the Netherlands are right-wing.

3.3 Omitted Variable Bias and Reverse Causality Play Limited Roles

A critique on the above specifications is that they might suffer from endogeneity problems. One source of endogeneity is omitted variable bias. Although adding political controls herewith accounting for ideological proximity to other parties in the last specification partly solves this problem (Ward, 2019), we also re-estimated out model using fixed effects logit and multinomial logit, in which only within-person variation over time is utilized. Table 5 presents transition matrices in voting intentions between time periods for the full sample, including the distinction between former incumbent and non-incumbent parties. Although many people do not switch parties over time, there remains enough variation within people to examine switches in voting preferences. With regard to right-wing populist parties, it can be observed that 69.6% of the people who intended to vote for a right-wing populist party when previously asked, will do so in the wave under study. Likewise, over 66.2% of the people who previously indicated they would vote for the left-wing populist party will do in the wave under study. Based on the transition matrix, it can be assumed that populist parties tend to attract new voters from other non-incumbent parties and non-voters. In contrast, people voting for incumbent parties in the past are likely to vote for incumbent parties but are not likely to switch to right-wing or left-wing populist parties.

The fixed effects estimations are presented in Table 6 and yield the same conclusions as our logit random effects and multinomial logit random effects estimations. Please note that in both a fixed-effects logistic regression and multinomial regression model, it is not possible to use observations that have no variation in voting intention. Hence, the number of observations in these models is much lower than in our baseline estimations. Because the fixed effects models remove omitted variable bias by focusing on changes within individuals across time (accounting for unknown personal characteristics), these models provide more conservative estimates of the association between subjective well-being and voting behavior. The fixed effects logit model shows that an increase in the subjective well-being index by 1 point decreases the chance of switching to a populist party (from not voting or voting on another party) by 8%. The multinomial fixed effects estimates show that if subjective well-being increases by 1 point, the odds to vote a right-wing populist and left-wing populist party (versus voting on the incumbent party) decrease by 10% and 12% respectively.

Another source of endogeneity and problem with the above specifications is that populist voters might be less happy because their party is not in power, inducing a reverse causality problem. We lack good instruments to do a proper instrumental variables (2SLS) estimation. However, to explore to what extent reverse causality is a problem, we estimated linear fixed effects models in which the dependent variable is subjective well-being and the independent variable are voting intentions for right-wing and left-wing populist parties at earlier points in time. If past voting intention (using a one-year lag)Footnote 11 is significantly associated with subjective well-being we could have a reverse causality issue. Table 7 shows the relevant parameter estimates of lagged voting intention for various specifications. These estimations indicate that a change in voting intention does not increase subjective well-being a year later. From this we conclude that reverse causality from voting behavior to subjective well-being is likely not a large issue.

3.3.1 Moderation Effects

The average association between subjective well-being and populist voting intention may obscure substantial differences across different groups of people. In other words, the relationship between subjective well-being on the one hand and voting intention on the other hand can be considered heterogeneous since lower subjective well-being scores may only under some circumstances result in voting for a populist party. Accordingly, we run an exploratory analysis in which we examine this heterogeneity by focusing on the interaction between subjective well-being and the socio-demographic and political control variables. Overall, none of the interactions between the socio-demographic control variables and subjective well-being index was statistically significant. With regard to the political control variables, we found that if people are unhappy and distrust parliament or democracy and/or perceive that income differences should decrease (which is also very much linked to trust; see Uslaner & Brown, 2005), they are more likely to vote populist than when they are unhappy and do not distrust (see Fig. 1A, B).Footnote 12

The explanation for this finding is straightforward. Voters can punish or reward the political elite for a deteriorated or improved personal situation, but they can also do so based on the standing of the country, irrespective of their own personal situation. However, when voters they still believe that the current political elite can solve issues, they are less inclined to vote for a populist party.

4 Concluding Remarks

The aim of our study was to investigate the connection between voting intention and subjective well-being using a vast database over a prolonged time frame (2008–2019). Our research discovered that a decrease in subjective well-being is linked to a higher likelihood of voting for a populist party, and this association remains even after considering other factors such as a decline in trust in political parties, democracy, and the economy, as well as political inclination. However, we found no indication of a relationship between subjective well-being and the intention to vote for non-incumbent parties other than populist ones. Our results are robust to reverse causality and omitted variable bias.

There are some limitations to these results. While the relationship between decreased subjective well-being and intention to vote for non-incumbent right-wing populist parties appears robust in our analyses, how much of this translates into actual votes for these parties is unclear. Voters may in practice vote for a different party as a reaction to additional information encountered in an actual election, such as whether a party has a chance of winning the elections, which parties are more likely to form coalitions, and the actual cost of physically participating in the election. This mismatch has been evident in the inaccuracy of political polls, even when conducted close to elections (Prosser & Mellon, 2018). It may be of interest for future research to investigate whether this relationship holds in actual elections as well.

Because not all unhappy people vote for populist parties, future research should look at the heterogeneity in the relationship between subjective well-being and populist voting in order to better understand the rise of populist parties. In other words, do particular kinds of people who attribute their decreased subjective well-being to societal circumstances switch to populist parties? In particular, it would be of interest if certain personality characteristics, related to the Big 5 personality traits, locus of control, hope and self-efficacy moderate the relationship between subjective well-being and voting behavior.

For those who perceive populism as a threat to current society, this research shows that restoring confidence in politics and reducing inequality is probably the best way to go forward (also given influencing personal subjective well-being is a more difficult way). In many Western societies people are currently disappointed with their leaders and outraged at a political elite that is out of touch with reality and self-serving. The Netherlands is not different. An old Dutch proverb states that trust arrives on foot and leaves on horseback, meaning it is difficult to gain and easy to lose. Hence, the populist movement is probably here to stay for a while. Following Kendall-Taylor and Nietsche (2020), to build trust, the existing political elite should try to avoid polarization, foster interactions between different groups in society, engage more with the ordinary citizen, and create a unifying, aspirational, coherent and concise narrative. Other strategies include the use of comprehensible language to communicate policy positions, focusing on shaping norms, and connecting to citizens with common values. Which strategies are more conducive is unclear yet. However, this could be examined in future research.

Notes

Even different explanations are provided for Trump’s win of the 2016 US Presidential election. Knuckey and Hassan (2022) associate the vote for Trump with anti-immigration sentiment and racial prejudice. Meanwhile Dorn et al. (2020) credit job losses related to computerization and globalization as factors for Trump’s success, with clear differences in responses among different ethnic and racial groups. Along these lines, status threat can be perceived as an important explanation for the Trump vote (Mutz, 2018).

In this regard, Hameleers et al. (2017, p. 870) argue that messages by populist parties are ‘generally characterized by assigning blame to elites in an emotionalized way’.

See, for example, the work by Liberini et al. (2017) that focuses on happiness and non-incumbent voting.

The Senate is indirectly elected by provincial councillors on the basis of proportional representation at the provincial elections.

Political party members (2–3% of Dutch population in period under study) are included in the analysis.

Particularly, these include Trots op Nederland (Proud of the Netherlands; TON) and VoorNederland (For the Netherlands; VNL).

See Appendix A for a more detailed classification of these parties.

In the period 2010–2012, Wilders’ PVV was ‘tolerating’ the VVD/CDA government, but not part of it.

Please note that in each LISS wave, the voting intention quesiton is usually asked at the end of the year, while the subjective well-being questions are asked in spring and summer (April-June) in the personality (life satisfaction and happiness) and work orientation (Cantril ladder) modules.

The figure for democracy moderation effect is available upon request.

References

Aarts, K., & Thomassen, J. (2008). Dutch voters and the changing party space 1989–2006. Acta Politica, 43(2), 203–234.

Algan, Y., Beasley, E., Cohen, D., & Foucault, M. (2018). The rise of populism and the collapse of the left-right paradigm: lessons from the 2017 French presidential election. Available at SSRN 3235586.

Arampatzi, E., Burger, M. J., Stavropoulos, S., & van Oort, F. G. (2019). Subjective well-being and the 2008 recession in European regions: The moderating role of quality of governance. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 2, 111–133.

Berman, S. (2019). Populism is a symptom rather than a cause: Democratic disconnect, the decline of the center-left, and the rise of populism in Western Europe. Polity, 51(4), 654–667.

Berman, S. (2021). The causes of populism in the west. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 71–88.

Bjørnskov, C. (2008). Social capital and happiness in the United States. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 3, 43–62.

Burger, M.J., Hendriks, M., & Ianchovichina, E. I. (2022). The anatomy of Brazil’s subjective well-Being in the 2010s: A tale of growing discontent and polarization. Working Paper.

Caiani, M., & Graziano, P. (2019). Understanding varieties of populism in times of crises. West European Politics, 42(6), 1141–1158.

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press.

Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 936–953.

Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2019). The surge of economic nationalism in Western Europe. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 128–151.

Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Majlesi, K. (2020). Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. American Economic Review, 110(10), 3139–3183.

Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harper.

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections: A micro-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 426–443.

Giebler, H., Hirsch, M., Schürmann, B., & Veit, S. (2021). Discontent with what? Linking self-centered and society-centered discontent to populist party support. Political Studies, 69(4), 900–920.

Guriev, S. (2018). Economic drivers of populism. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108, 200–203.

Halmai, G. (2018). Is there such thing as ‘Populist Constitutionalism’? The case of Hungary. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 11, 323–339.

Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & De Vreese, C. H. (2017). “They did it”: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900.

Hasanović, J. (2015). Ochlocracy in the practices of civil society: A threat for democracy? Studia Juridica Et Politica Jaurinenisis, 2(2), 56–66.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2017). Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: The silent revolution in reverse. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 443–454.

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23.

Kendall-Taylor, A., & Nietsche, C. (2020). Combating populism: A toolkit for liberal democratic actors. Center for a New American Security.

Kleinnijenhuis, J. et al. (2003) De puinhopen in het nieuws. De rol van de media bij de Tweede-Kamerverkiezingen van 2002, Alphen aan den Rijn-Malines.

Knoef, M., & De Vos, K. (2009). The representativeness of LISS: An online probability study (pp. 1–29). Universiteit van Tilburg.

Knuckey, J., & Hassan, K. (2022). Authoritarianism and support for Trump in the 2016 presidential election. The Social Science Journal, 59(1), 47–60.

Kovács, K., & Scheppele, K. L. (2018). The fragility of an independent judiciary: Lessons from Hungary and Poland—And the European Union. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 51(3), 189–200.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-term fluctuations in US voting behavior, 1896–1964. American Political Science Review, 65(1), 131–143.

Kriesi, H. (1998). The transformation of cleavage politics The 1997 Stein Rokkan lecture. European Journal of Political Research, 33(2), 165–185.

Levitsky, S., & Loxton, J. (2012). Populism and competitive authoritarianism. Populism in Europe and the Americas Threat or Corrective for Democracy, 160–181.

Liberini, F., Redoano, M., & Proto, E. (2017). Happy voters. Journal of Public Economics, 146, 41–57.

Lindholm, A. (2020). Does Subjective Well-Being Affect Political Participation?. Swiss Journal of Sociology, 46(3).

Löfflmann, G. (2019). America First and the populist impact on US foreign policy. Survival, 61(6), 115–138.

Lucardie, P. (2008). The Netherlands: populism versus pillarization. Twenty-first century populism: The spectre of Western European democracy, 151–165.

March, L. (2011). Radical Left Parties in Europe. Routledge.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563.

Mutz, D. C. (2018). Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(19), E4330–E4339.

Nai, A. (2021). Fear and loathing in populist campaigns? Comparing the communication style of populists and non-populists in elections worldwide. Journal of Political Marketing, 20(2), 219–250.

Nowakowski, A. (2021). Do unhappy citizens vote for populism? European Journal of Political Economy, 68, 101985.

Otjes, S., & Louwerse, T. (2015). Populists in parliament: Comparing left-wing and right-wing populism in the Netherlands. Political Studies, 63(1), 60–79.

Ouweneel, P., & Veenhoven, R. (2016). Happy protest voters: The case of Rotterdam 1997–2009. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 739–756.

Pellikaan, H., Lange, S. L. D., & Meer, T. V. D. (2007). Fortuyn's legacy: Party system change in the Netherlands. Comparative European Politics, 5, 282–302.

Prosser, C., & Mellon, J. (2018). The twilight of the polls? A review of trends in polling accuracy and the causes of polling misses. Government and Opposition, 53(4), 757–790.

Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., & Taggart, P. (2019). The PopuList: An overview of populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic parties in Europe.

Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368.

Savelkoul, M., & Scheepers, P. (2017). Why lower educated people are more likely to cast their vote for radical right parties: Testing alternative explanations in The Netherlands. Acta Politica, 52(4), 544–573.

Schumacher, G., & Rooduijn, M. (2013). Sympathy for the ‘devil’? Voting for populists in the 2006 and 2010 Dutch general elections. Electoral Studies, 32(1), 124–133.

Thomassen, J. (2000). Politieke veranderingen en het functioneren van de parlementaire democratie in Nederland, in Thomassen, J., Aarts, K. and van der Kolk, H. (eds) Politieke veranderingen in Nederland, 1971−1998. Kiezers en de smalle marges van de politiek, The Hague: Sdu

Tubadji, A., Webber, D., & Burger, M.J. (2023). Geographies of feeling stuck behind and populist voting in the Netherlands. Working Paper.

Uslaner, E. M., & Brown, M. (2005). Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research, 33(6), 868–894.

Van der Waal, J., & De Koster, W. (2018). Populism and support for protectionism: The relevance of opposition to trade openness for leftist and rightist populist voting in The Netherlands. Political Studies, 66(3), 560–576.

Van Leeuwen, E. S., Halleck Vega, S., & Hogenboom, V. (2021). Does population decline lead to a “populist voting mark-up”? A case study of the Netherlands. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(2), 279–301.

Van Wijk, D., Bolt, G., & Tolsma, J. (2020). Where does ethnic concentration matter for populist radical right support? An analysis of geographical scale and the halo effect. Political Geography, 77, 102097.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess how happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. In: Happiness, Economics and Politics: Towards a Multi-disciplinary Approach, 45–69.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 1–39.

Volkens, A., & Klingemann, H. D. (2002). Parties, Ideologies and Issues: Stability and Change in Fifteen European Party Systems 1945–1998. In K. R. Luther & F. MüllerRommel (Eds.), Political Parties in the New Europe: Political and Analytical Challenges. Oxford University Press. Cham.

Vossen, K. P. S. S. (2016). The different flavours of populism in the Netherlands. Giusto, H.; Kitching, D.; Rizzo, S.(ed.), The Changing Faces of Populism: Systemic Challengers in Europe and the US, 173–191.

Ward, G. (2019). Happiness and voting behaviour. World Happiness Report, 2019, 46–65.

Ward, G., De Neve, J. E., Ungar, L. H., & Eichstaedt, J. C. (2021). (Un) happiness and voting in US presidential elections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 370.

Whitten, G. D., & Palmer, H. D. (1996). Heightening comparativists' concern for model choice: Voting behavior in Great Britain and the Netherlands. American Journal of Political Science, 231–260.

Witte, C. T., Burger, M. J., & Ianchovichina, E. (2020). Subjective well-being and peaceful uprisings. Kyklos, 73(1), 120–158.

Zaslove, A. (2008). Here to stay? Populism as a new party type. European Review, 16(3), 319–336.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics and Informed Consent

For the data analysis, we made use of secondary data using the LISS panel. Information about ethics and informed consent regarding the LISS panel can be found here: https://www.lissdata.nl/faq-page/how-are-ethics-and-consent-organized-liss-panel.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table

Appendix B

See Table

Appendix C

Descriptive statistics of baseline variable.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the subjective well-being index in the Netherlands. In line with other studies on the Netherlands (Veenhoven, 2009), average subjective well-being in the Netherlands is high (7.5), where most respondents score between 7 and 8. Table 10 shows descriptive statistics for the variables in the baseline regressions (N = 28,913).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burger, M.J., Eiselt, S. Subjective Well-Being and Populist Voting in the Netherlands. J Happiness Stud 24, 2331–2352 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00685-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00685-9