Gratitude makes sense of our past, brings peace for today, and creates a vision for tomorrow.

Melody Beattie

Abstract

The current study examined the associations between time perspective, dispositional gratitude, and life satisfaction. The aim of the study was to check if gratitude mediates the relationship between time perspectives and life satisfaction. The participants were 591 Polish people aged 18–73 (M = 30, SD 5.45). We used several measures: the Satisfaction with Life Scale, the Gratitude Questionnaire, the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, the Carpe Diem Scale, and the Present-Eudaimonic Time Perspective Scale. We found that gratitude played a mediating role between the dimensions of time perspective and life satisfaction. The presented results were interpreted in the context of the Pollyanna effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A great number of studies have indicated the central role of time perspective with regard to well-being (Cunningham et al. 2015; Stolarski 2016), life satisfaction (Stolarski et al. 2016), and meaning in life (Przepiórka 2012). Other studies also highlighted the unique role of time perspective as a predictor of both mental health and wisdom even after controlling for demographic, physical health, and personality variables (Webster et al. 2014). Zhang and Howell (2011) found that past time perspectives were the most significant predictors of life satisfaction and mediators of the relationships between personality traits and life satisfaction. Finding a construct that may help to account for the relationship between time perspectives and life satisfaction will bring a better understanding of the nature of life satisfaction and will help, to some extent, to answer the everlasting questions: What makes us happy? Why are some people happier than others? Recent findings showed that dispositional gratitude mediated the relationship between a past-positive time frame and various indicators of well-being (Bhullar et al. 2015). In the present study, we extended this search to include the question of how the link between past, present, and future time orientations and life satisfaction may be mediated by gratitude. We examined not only Past-Positive, but also Past-Negative, Present-Hedonistic, Present-Fatalistic, Future, Carpe Diem, and Present-Eudaimonic time perspectives. This was meant to give us a broader picture of the role of time perspective and gratitude in achieving happiness.

1.1 Time Perspective

Human activity, experiences, and decisions are immersed in time, and there is no way to separate them. Time in psychology is perceived as an individual system of filing events. Using the temporal structures in the brain, some events—taking place in the present—are organized according to their sequence; the remaining events are temporally coded ex post (Nosal 2010). Time perspective (TP) is understood as a multidimensional construct associated with the person’s ability to anticipate future events and distance themselves from the past (Nuttin 1984). The way human experience is processed with the temporal framework of past, present, and future to allow us to speak of a certain time perspective (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999). According to their definition, time perspective is “the often nonconscious process whereby the continual flows of personal and social experiences are assigned to temporal categories, or time frames, that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to those events’’ (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, p. 1271).

Time perspective as conceptualized by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) is one of the most well-known and widely discussed in the literature and research theory (e.g., Birkas and Csatho 2015; Carelli et al. 2011; Drake et al. 2008; Milfont et al. 2008; Siu et al. 2014; Wiberg et al. 2012). It is a multifaceted approach to attitude towards time, since it distinguishes five different time perspectives: Past-Positive, Past-Negative, Present-Fatalistic, Present-Hedonistic, and Future. These temporal categories organize individual differences, giving them meaning and coherence (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, 2008). People with a predominant past time orientation live in the world of their experiences and memories—traumatic or pleasant. Others are completely absorbed by current events, paying little attention to their future consequences and only minimally taking past experiences into account. Future-oriented individuals exhibit a somewhat different pattern of functioning (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, 2008). They forget about the pleasures of the present because their entire activity is subordinated to the future. The results of several studies confirm that the types of TP distinguished by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) are significantly linked to several important aspects of human functioning. TP is associated with self-esteem, energy, happiness, life satisfaction, mindfulness, and affect (Boniwell and Zimbardo 2004; Daugherty and Brase 2010; Klingeman 2001; Drake et al. 2008; Sobol-Kwapinska 2013; Sobol-Kwapinska et al. 2016a; Stolarski et al. 2014; Zhang and Howell 2011; Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, 2008; Zimbardo et al. 1997).

As researchers (Vowinckel et al. 2015; Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, 2008) have pointed out many times that it is necessary to approach present time orientation more broadly and to introduce its additional measures, in our study we introduced additional types of present time orientation to examine the link between time perspective and life satisfaction, namely Carpe Diem (CD) perspective (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013) and present-eudaimonic (PE) time perspective (Vowinckel et al. 2015).

CD is an active orientation defined as a focus on the here and now, regardless of whether the present is a source of pleasure or not (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013; Sobol-Kwapinska and Jankowski 2016). The main emphasis in CD is placed on the significance of the present moment and on the awareness of its uniqueness (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013); however, unlike hedonism or fatalism (see Zimbardo and Boyd 1999), CD is a present time perspective associated with positive functioning. Previous studies (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013; Sobol-Kwapinska and Jankowski 2016) revealed positive links between CD and meaning in life, positive affect, focus on goal setting and goal pursuit as well as a generally positive evaluation of life and time.

PE is “a positive present orientation that can serve to complement the affect-laden past and future scales of the BTPS” (Balanced Time Perspective Scale; Vowinckel et al. 2015, p. 206). This perspective relates to the eudaimonic approach, which means living a complete and fully satisfying life (Deci and Ryan 2000). This dimension of the present differs from the hedonistic approach; it is based on the concepts of mindfulness and flow as complete absorption in the here and now (see Csikszentmihalyi 1990), since two processes are related to eudaimonic well-being. A number of studies have underlined the key role of the experience of flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Ryan and Deci 2001) and mindfulness (Baer 2009; Brown and Ryan 2003; Keng et al. 2011; Segal et al. 2002) in contribution to health and well-being. Present-Eudaimonic perspective is a focus on one’s feelings and experiences in the present moment. It is an openness to the here and now and consists in enjoying the pleasure of being here and now. This present orientation makes it similar to Carpe Diem, but there is a difference: while Carpe Diem perspective is a focus on the present time, Present-Eudaimonic perspective is a focus on one’s feelings, thoughts, and emotions here and now. People high in Carpe Diem perspective are focused on the present moment because they believe that the present is the most important dimension of time. People high in Present-Eudaimonic perspective tend to be focused on themselves—on their own feelings and experiences. They concentrate on the present above all because they want to experience positive emotions, such as peace and joy.

1.2 Gratitude and Well-Being

According to the body of literature, gratitude can be viewed as an emotion (Algoe et al.2013; Williams and Bartlett 2014), a mood (Rosenberg 1998), a personality trait (Wood et al. 2008), a moral virtue (Emmons and McCullough 2003; McCullough et al. 2001), a habit (Emmons and McCullough 2003), a motive (McCullough et al. 2004), and a way of life (Jia et al. 2014).

Gratitude occurs when individuals perceive that they have obtained an intentional benefit from another person or from the higher being (Jia et al.2014). Gratitude is an other-oriented emotion, since people tend to feel grateful precisely when they receive a benefit provided by another person (Tagney et al. 2007).

A number of studies confirmed the role of gratitude in predicting well-being (Emmons and Shelton 2002; Froh et al. 2009). Bryant et al. (2005) examined the role of reminiscence in positive affective experience. It was proved that reminiscing about pleasant memories was related to positive emotional experience. It turns out that the intensification of reminiscence is a very good strategy to increase the sense of happiness—better than focusing on the present only. The group that focused on pleasant memories enjoyed life more than groups not focusing on the past. Allemand and Hill (2016) found evidence for age effects in gratitude, but only for the subjective age with respect to future time perspective specifically to the remaining opportunities. Future time perspective mediated the relation between chronological age and general gratitude; namely, the perception of future time as open was related to higher gratitude. There was a positive relationship between the remaining opportunities and gratitude.

1.3 The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of time perspectives and gratitude in relations to life satisfaction. In what way can people’s attitude towards time contribute to their sense of happiness? Can gratitude mediate this relationship? We hypothesized that time perspective would be related to perceived life satisfaction; we also expected that gratitude would play the role of a mediator between time perspectives and life satisfaction.

Time is life. To live is to spend time in a particular way. It can therefore be said that attitudes towards life are linked to attitudes towards time (Przepiórka 2012). Gratitude for what life brings is associated with gratitude for time (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013; Szczesniak and Timoszyk-Tomczak 2018; Zimbardo et al. 1997; Zimbardo and Boyd 2008). Positive attitude towards time includes a feeling of gratitude for the time of life (Zimbardo and Boyd 2008). We therefore expected that relationships between attitudes towards the past, present, and future and satisfaction with life would be explained by the attitude of gratitude for life. Positive evaluation of time is largely associated with the ability to notice the positive aspects of life and with a focus on them (Szczesniak and Timoszyk-Tomczak 2018), while negative attitude towards time is associated, above all, with perceiving and focusing on the negative aspects of life (Stolarski et al. 2015). Every person’s life consists of both pleasant and unpleasant moments and experiences (Sword et al. 2014). Generally speaking, everyone’s past is, in some respects, positive and contains positive events, but in some respects it is negative and includes disagreeable memories. The same refers to the remaining dimensions of time: the present and the future. Whether a person is more focused on the positive or negative sides of each dimension of time depends on him or her (Sobol-Kwapinska 2009, 2013). Paying attention to the positive sides of the past, present, and future results in perceiving life not as a burden but as a gift to be grateful for. The feeling of gratitude contributes to general satisfaction with life, even though it has ups and downs, being pleasant on some occasions and unpleasant on others (Lopez and Snyder 2011). The attitude of gratitude also makes people capable of looking even at unpleasant life events as something that has brought them some kind of benefit (Sword et al. 2014).

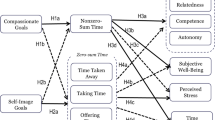

Focusing on the positive aspects of time, recalling positive past events, or imagining positive future events inspires a sense of gratitude for them regardless of which dimension of time they belong to (Szczesniak and Timoszyk-Tomczak 2018). Present-hedonistic perspective is a focus on the pleasures experienced here and now—on the pleasant and positive aspects of time. Carpe Diem perspective is a focus on each present moment, which is evaluated as the most important point in time. Eudaimonic perspective is a focus on pleasant feelings associated with being open and present in the here and now. Similarly, future perspective as defined by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999, 2008) is a focus on goals and thinking about the pleasant aspects of the future. Therefore, the mechanism explaining the relations between time perspective and life satisfaction through the attitude of gratitude applies also to the present and future time perspectives. This mechanism can be presented as follows: focus on pleasant and positive aspects of time/events—attitude of gratitude, stemming from the sense of having received the good moments of life from fate—the attitude of gratitude increases positive evaluation of events and inspires perceiving them in the context of the gifts one has received (Fig. 1).

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The participants in the study were a group of 591 Poles aged 18–73 (M = 30, SD 5.45); 51% of the sample were women. We recruited the participants via a research panel, accessible online. Invitation to take part in the study was sent out to registered users of the panel. The research project received approval from the institutional review board of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Potential participants were informed about the study and were asked if they wished to participate in it. Those who agreed were given a link to the questionnaires. We sent out 800 invitations, to which we received replies from 600 people; nine contributions were incomplete and therefore excluded from analyses. Panel users make up a representative sample reflecting the general Polish population in terms of gender distribution, place of residence, education, and employment status. They receive extra loyalty points for their participation, which can be exchanged for prizes in kind. As regards occupational status, 49% of the participants had an employment contract, 8% reported having a commission contract, 3% reported having a contract for specific work, 7% ran their own business, 10% reported that they were unemployed, 19% were retired, 5% were university students, and 2% were school students. As far as relationship status was concerned, 26% of the participants were single, 56% were married, and 19% were in a non-formalized relationship. Sixty-eight percent of the sample had children. As regards the place of residence, 20% of the participants lived in the countryside, 12% lived in a small town (with up to 20,000 residents), 23% lived in a medium-sized town (between 20,000 and 100,000 residents), 26% lived in a large town (between 100,000 and 500,000 residents), and 20% lived in a big city (with a population of over 500,000).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Life Satisfaction

To measure life satisfaction, we administered the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) as adapted into Polish (Juczynski 2009), consisting of five items, which respondents rate on a seven-point scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). The scale measures global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one’s life (e.g., “The conditions of my life are excellent”).

2.2.2 Gratitude

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6; McCullough et al. 2002) as adapted into Polish by Kossakowska and Kwiatek (2015) is a brief measure of gratitude disposition. It is a six-item self-report scale, and the items are rated on a Likert-scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The questionnaire includes, for example, the following item: “I am grateful to a wide variety of people.”

2.2.3 Time Perspective

To measure time perspective, we used the 56-item ZTPI (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999) as adapted into Polish (Sobol-Kwapinska et al. 2016b). The instrument consists of 56 items making up five scales, measuring five time perspectives. The Past-Positive scale measures the focus on positively evaluated past (e.g., “It gives me pleasure to think about my past”). The Past-Negative scale measures the tendency to focus on the negative past (e.g., “I think about the bad things that have happened to me in the past”). The Present-Hedonistic scale measures hedonistic focus on pleasures experienced in the “here and now” without considering the consequences of one’s behavior (e.g., “I take risks to put excitement in my life”). The Present-Fatalistic scale measures fatalistic focus on the present combined with the belief that one has no influence on the future (e.g., “My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence”). The Future scale measures focus on the future, making future plans, and formulating future goals (e.g., “I complete projects on time by making steady progress”). The items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very untrue of me, 5 = very true of me).

2.2.4 Carpe Diem Time Perspective

The Carpe Diem Scale (CD; Sobol-Kwapinska 2013) measures active focus on the present (i.e., on the current situation) combined with perceiving the here and now as precious and important. This scale consists of 12 items (e.g., “What happens in the present is very vital for my life”). Respondents answer using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = very untrue to 5 = very true).

2.2.5 Present-Eudaimonic Time Perspective

The Present-Eudaimonic Time Perspective Scale (PE; Vowinckel et al. 2015) is based on the concepts of mindfulness and flow. It measures positive eudaimonic attitude towards the present, understood as focusing on one’s feelings, thoughts, and emotions here and now. It consists of 10 items (e.g., “I feel a certain peace and harmony when I stay focused on the flow of the present”), each with a response scale from 1 (1 = very untrue to 5 = very true). The PE was translated into Polish by one of the authors of this paper (A.P.). The Polish version was translated back into English by a professional English translator, and the original English version was compared with the back-translated English version. A board comprised of four psychology students and one PhD student checked the translation of the scale in terms of comprehensibility and readability and did not express any reservations about it.

The measures administered had been successfully used in other Polish studies; for instance, the Gratitude Questionnaire had previously been used, by Szczesniak and Timoszyk-Tomczak (2018), the 56-item ZTPI—by Sobol-Kwapinska and Jankowski (2016), and the Carpe Diem Scale—by Sobol-Kwapinska (2013). All scales had good reliability and validity both in previous studies and in the present one. The values of Cronbach’s alpha for each of the instruments used in the present study are presented in Table 1. As one item of the PE Scale (“Being in the present helps me appreciate what I have”) may overlap with gratitude, we excluded this item from the analyses. The results are reported in the supplementary material (Supplementary A). The omission of the overlapping item did not change the results significantly. Therefore, it is the scores on the full version of the PE Scale that are presented in the text.

3 Results

Scores on SWLS, FQ-6, ZTPI, CD, and PE did not differ significantly between genders and were normally distributed. To investigate the relationship between TP measures, gratitude, and life satisfaction, we computed Pearson’s correlations (see Table 1). Life satisfaction correlated negatively with Past-Negative TP and positively with Past-Positive, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Carpe Diem, and Eudaimonic TPs as well as with gratitude. Gratitude correlated positively with Past-Positive, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Carpe Diem, and Present Eudaimonic TPs, and negatively with the Past-Negative and Present-Fatalistic TPs.

Path modelling was used for mediation testing. In order to test the more complex relationships between the variables, we ran mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes 2013) with 5000 bootstrapped samples, following the procedure recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Table 2 presents the details of these analyses. The present study showed that gratitude accounted for a significant proportion of variance in the relationship between almost all of the time perspective indices and life satisfaction. Gratitude was not a mediator in the Carpe Diem TP-life satisfaction link.

We also computed the reverse models (with gratitude as an independent variable and time perspective as a mediator). In these models (presented in the Supplementary material B) there were smaller indirect effects than in the proposed ones.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this article was to examine the role of gratitude in the relationship between various types of time perspective and life satisfaction. It turned out that perspectives involving a positive attitude towards time (Past-Positive, Present-Hedonistic, Eudaimonic, Carpe Diem, and Future TPs) were related to a higher level of gratitude and to higher life satisfaction. This is in line with studies showing that positive views of the past were related to happiness while negative views of the past were linked to depression (Stolarski et al. 2014; Zimbardo and Boyd 1999). The results of our study suggest that gratitude may partly explain the positive relationship between positive time perspectives (i.e., enjoying the present, past, and future) and life satisfaction. Likewise, the lack of gratitude explains the fact that negative attitude towards the past, present, and future is linked to low life satisfaction.

These relationships can be understood in the context of the Pollyanna principle (Matlin and Stang 1978)—a tendency to focus on the positive aspects of events and to ignore negative ones. Positive time perspective is associated precisely with this kind of tendency to focus on the positive aspects of time, and therefore it evokes a feeling of gratitude for them, thus leading to a positive evaluation of life in general (Szczesniak and Timoszyk-Tomczak 2018). Similarly, negative time perspective is linked with the lack of tendency to focus on pleasant aspects of events and to place emphasis on what is unpleasant or painful in life. This in turn causes a feeling of bitterness rather than gratitude and leads to a negative evaluation of life in general.

The study revealed that the mediating effect of gratitude was the strongest in the relationship between Past-Positive perspective and life satisfaction. Our results show that people who view their past positively, in the light of gratitude, feel the strongest life satisfaction. These results are in line with a previous study by Bhullar et al. (2015), where gratitude was found to be a mediator between Past-Positive perspective and life satisfaction. Focus on the past, cultivating life time—the aspects associated with attitude towards the past—are linked to higher life satisfaction. These results are consistent with the literature, where it is shown that individuals who feel stronger nostalgia as well as pleasure and contentment report higher life satisfaction (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, 2008). This result can be explained in the light of previous studies on nostalgia understood as a sentimental longing for one’s past, which suggests its important role in the experience of life satisfaction and positive affect as well as in reducing loneliness (Baldwin 2016; Cox et al. 2015). Other research results also suggest that looking back into the past and deriving patterns from it in a way that may improve the individual’s functioning in the present and in the future is beneficial and even necessary (Zaleski 1988).

In the present study, we have found that future TP is related to life satisfaction and that this relationship is mediated by gratitude. It has been confirmed that the abilities to set goals, to anticipate, and to plan are important for well-being in accordance with the theory of goal-setting (for a review, see Emmons 1986; Sheldon and Elliot 1999). Recent meta-analysis showed that future TP was positively associated with life satisfaction and subjective health (Kooij et al. 2018). From previous studies we know that future TP is related to individual motivation in different areas of our life and behavior, such as education, work, or environment (Andre et al. 2018). This future orientation brings many beneficial outcomes, also contributing to people’s happiness through the ability to be grateful for what may come and what we expect to come in the future.

In the case of present hedonistic TP, our study has confirmed that gratitude plays a mediating role in the relationship between this present TP and life satisfaction. Focusing on pleasures in the present, seeking novelty and sensation intensifies gratitude and is a good strategy enhancing life satisfaction. In accordance with this finding, other study by Desmyter and De Raedt (2012) showed that present hedonistic TP was related to a high positive affect. It is a strategy analogous to counting the good things experienced every day or counting reasons for gratitude (Rash et al. 2011; Wood et al. 2010). The relations between eudaimonic time perspective, gratitude, and life satisfaction are similar. Focusing on one’s experience here and now helps to appreciate the present moment (Vowinckel et al. 2015).

By contrast, Present-Fatalistic TP, associated with a tendency to focus on the negative aspects of time (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999), is related to lower gratitude. Present-Fatalistic perspective is the belief that life is determined by fate, which means it is not worth planning for the future, because a person has no control over time. Passively waiting for a stroke of luck and for life itself to bring good moments is usually fruitless. Happy moments do not arrive by themselves and people may not notice anything to be grateful for; as a result, they experience lower happiness.

Only the relationship between Carpe Diem TP and life satisfaction was not explained by gratitude. This can be seen as stemming from the fact that a person with strong Carpe Diem perspective tries to focus on every here and now, regardless of whether the present is pleasant or disagreeable. For this reason, this kind of focus on the present is not always associated with gratitude. Carpe Diem perspective is linked to the evaluation of time as valuable and unique (Sobol-Kwapinska 2013) but not always pleasant.

5 Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of the present study have to be noted. Firstly, the cross-sectional design demands caution in the interpretation of the causality of the findings. Secondly, the study was based on self-report methods, in which people declare their inner state of feeling gratitude. In the future, it would be recommendable to take a life span perspective into account as well in order to verify the investigated relationships across different age groups and to see whether at different life stages gratitude plays a similar role as a mediator between time perspectives and life satisfaction.

6 Conclusion

In the present study we examined the potential determinants of life satisfaction with a special focus on time perspective indices and gratitude. The results of our study cast a new light on the explanations of the relationship between time perspective and subjective well-being. Our results have shown that dispositional gratitude, which is linked to appreciating and being grateful for the positive aspects of life, mediates the associations between TP indices and life satisfaction. Being grateful for what one has received in the past, for what one currently has, and for what the future will bring may significantly increase one’s sense of satisfaction. This result shows that a positive perspective on one’s past as well as focusing on the present and the future by a genuine attitude of gratitude leads to a higher level of life satisfaction. We can conclude that people who have a positive TP and experience more gratitude are more satisfied with their lives thanks to this attitude. The positive reframing of the time and being grateful can therefore be good ways of promoting well-being.

References

Algoe, A. B., Fredrickson, B. L., & Gable, S. L. (2013). The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion, 13(4), 605–609.

Allemand, M., & Hill, P. L. (2016). Gratitude from early adulthood to old age. Journal of Personality, 84(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12134.

Andre, L., van Vianen, A., Peetsma, T., & Oort, F. (2018). Motivational power of future time perspective: Meta-analyses in education, work, and health. PLoS ONE, 13(1), E0190492.

Baer, R. A. (2009). Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 15–20.

Baldwin, M. (2016). Bringing the past to the present: Temporal self-comparison processes moderate nostalgia’s effect on well-being. Dissertation Abstracts International, 76.

Bhullar, N., Surman, G., & Schutte, N. (2015). Dispositional gratitude mediates the relationship between a past-positive temporal frame and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 52–55.

Birkas, B., & Csatho, A. (2015). Size the day: The time perspectives of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 318–320.

Boniwell, I., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). Balancing time perspective in pursuit of optimal functioning. In P. A. Linley, S. Joseph, P. A. Linley, & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 165–178). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Bryant, F. B., Smart, C. M., & King, S. P. (2005). Using the past to enhance the present: Boosting happiness through positive reminiscence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 227–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-3889-4.

Carelli, M. G., Wiberg, B., & Wiberg, M. (2011). Development and construct validation of the Swedish Zimbardo time perspective inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000076.

Cox, C. R., Kersten, M., Routledge, C., Brown, E. M., & Van Enkevort, E. A. (2015). When past meets present: The relationship between website-induced nostalgia and well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(5), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12295.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Cunningham, K. F., Zhang, J. W., & Howell, R. T. (2015). Time perspectives and subjective well-being: A dual-pathway framework. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, W. van Beek, M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory: Review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 403–415). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07368-2_26.

Daugherty, J. R., & Brase, G. L. (2010). Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 202–207.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and the “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Desmyter, F., & De Raedt, R. (2012). The relationship between time perspective and subjective well-being of older adults. Psychologica Belgica, 52(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-52-1-19.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Drake, L., Duncan, E., Sutherland, F., Abernethy, C., & Henry, C. (2008). Time perspective and correlates of well-being. Time & Society, 17(1), 47–61.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1058–1068.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389.

Emmons, R. A., & Shelton, C. M. (2002). Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 459–471). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, Ch., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633–650.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Jia, L., Tong, E. M. W., & Lee, L. N. (2014). Psychological “gel” to bind individuals’ goal pursuit: Gratitude facilitates goal contagion. Emotion, 14(4), 748–760.

Juczynski, Z. (2009). Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji i psychologii zdrowia [Measurement instruments in health promotion and psychology]. Warsaw: Psychological Test Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056.

Klingeman, H. (2001). The time game: Temporal perspectives of patients and staff in alcohol and drug treatment. Time & Society, 10(2–3), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X01010002008.

Kooij, D., Kanfer, R., Betts, M., & Rudolph, C. (2018). Future time perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(8), 867–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000306.

Kossakowska, M., & Kwiatek, P. (2015). Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6 [Polish adaptation of the Gratitude Questionnaire]. Przegląd Psychologiczny, 57(4), 503–514.

Lopez, S., & Snyder, C. R. (2011). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.)., Oxford library of psychology Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matlin, M. W., & Stang, D. J. (1978). The Pollyanna principle: Selectivity in language, memory, and thought. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Pub. Co.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249–266.

McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J. A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 295–309.

Milfont, T. L., Andrade, T. L., Belo, R. P., & Pessoa, V. S. (2008). Testing Zimbardo time perspective inventory in a Brazilian sample. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 42, 49–58.

Nosal, C. S. (2010). Czas w umyśle człowieka. Struktura przestrzeni temporalnej [Time in the human mind: The structure of temporal space]. In S. Bedyńska & G. Sędek (Eds.), Życie na czas: Perspektywy badawcze postrzegania czasu [Living on time: Research perspectives on time perception] (pp. 365–397). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Nuttin, J. (1984). Motivation, planning, and action. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Przepiórka, A. (2012). The relationship between attitude towards time and the presence of meaning in Life. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 2(3), 22–30.

Rash, J. A., Matsuba, M. K., & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology-Health and Well Being, 3(3), 350–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology, 2, 247–270.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Sheldon, K. G., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 152–165.

Siu, N. Y. F., Lam, H. H. Y., Le, J. J. Y., & Przepiorka, A. (2014). Time perception and time perspective differences between adolescents and adults. Acta Psychologica, 151, 222–229.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M. (2013). Hedonism, fatalism and carpe diem: Profiles of attitudes towards the present time. Time & Society, 22(3), 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X13487043.

Sobol-Kwapińska, M. (2009). Forms of present time orientation and satisfaction with life in the context of attitudes toward past and future. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 37(4), 433–440.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M., & Jankowski, T. (2016). Positive time balanced time perspective and positive orientation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1511–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9656-2.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M., Jankowski, T., & Przepiorka, A. (2016a). What do we gain by adding time perspective to mindfulness? Carpe Diem and mindfulness in a temporal framework. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.046.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M., Przepiorka, A., & Zimbardo, P. (2016b). The structure of time perspective: Age-related differences in Poland. Time & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X16656851.

Stolarski, M. (2016). Not restricted by their personality: Balanced time perspective moderates well-established relationships between personality traits and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 100, 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.037.

Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., & Van Beek, W. (Eds.). (2015). Time perspective theory: Review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo. Cham: Springer.

Stolarski, M., Matthews, G., Postek, S., Zimbardo, P. G., & Bitner, J. (2014). How we feel is a matter of time: Relationships between time perspective and mood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 809–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9450-y.

Stolarski, M., Vowinckel, J., Jankowski, K. S., & Zajenkowski, M. (2016). Mind the balance, be contented: Balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.039.

Sword, R. M., Sword, R. K. M., Brunskill, S. R., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2014). Time perspective therapy: A new time-based metaphor therapy for PTSD. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19(3), 197–201.

Szczesniak, M., & Timoszyk-Tomczak, C. (2018). A time for being thankful: Balanced time perspective and gratitude. Studia Psychologica: Journal for Basic Research in Psychological Sciences, 60(3), 150–166.

Tagney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). What’s moral about the self-conscious emotions? In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 21–37). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Vowinckel, J. C., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Webster, J. D. (2015). Flourishing in the now: Initial validation of a present-eudaimonic time perspective scale. Time & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15577277.

Webster, J. D., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Westerhof, G. J. (2014). Time to flourish: The relationship of temporal perspective to well-being and wisdom across adulthood. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 1046–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.908458.

Wiberg, M., Sircova, A., Wiberg, B., & Carelli, M. G. (2012). Operationalizing balanced time perspective in a Swedish sample. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 12(1), 95–107.

Williams, L. A., & Bartlett, M. Y. (2014). Warm thanks: Gratitude expression facilitates social affiliation in new relationships via perceived warmth. Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000017.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Stewart, N., Linley, P., & Joseph, S. (2008). A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion, 8(2), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281.

Zaleski, Z. (1988). Transtemporalne “JA”: osobowość w trzech wymiarach czasowych [Transtemporal self: Personality in the three dimensions of time]. Przegląd Psychologiczny, 4, 931–943.

Zhang, J. W., & Howell, R. T. (2011). Do time perspectives predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond personality traits? Personality and Individual Differences, 50(8), 1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.021.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid reliable individual differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1271–1288.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The time paradox. New York, NY: Free Press.

Zimbardo, P. G., Keough, K. A., & Boyd, J. N. (1997). Present time perspective as a predictor of risky driving. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(6), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00113-X.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland No. 2017/25/B/HS6/00935.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Przepiorka, A., Sobol-Kwapinska, M. People with Positive Time Perspective are More Grateful and Happier: Gratitude Mediates the Relationship Between Time Perspective and Life Satisfaction. J Happiness Stud 22, 113–126 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00221-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00221-z