Abstract

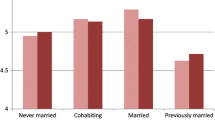

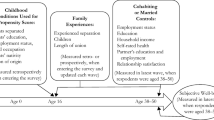

Using Taiwan’s PSFD data and within-between panel data models, this study investigated the relation between marriage and happiness. It did not find a selection effect, indicating that there is no statistical evidence that married people were happier two or more years before getting married. There was a honeymoon effect during the marriage year. Several samples were constructed to investigate whether happiness level quickly returned to the baseline after marriage. The results of most samples showed that the happiness levels were significantly higher than the baseline within 3 years of marriage. Although the happiness level after the fourth year of marriage is not significant, its magnitude is not small, indicating a diversity of happiness status after 3 years of marriage. Marriage, on average, enhances happiness more and longer for women than for men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lucas et al. (2003) stressed that the happiness quick return to the baseline after marriage is the average trend, and there is a great diversity among individuals.

Musick and Bumpass (2012) did not intend to investigate the issue of adaptation, but their findings do not espouse full adaptation.

Although Fig. 2 in Stutzer and Frey (2006) showed that satisfaction with life after marriage declined to the level of five years before marriage, they did not see this result as support of full adaptation. They stated (pp. 11–12): “Whether this adaptation is truly hedonic, or whether married people start using a different scaling for what they consider a satisfying life (satisfaction treadmill), is difficult to assess,” and “Given the strong pattern in the age-life satisfaction profile, conclusions about full adaptation or that there is no marriage effect, however, are difficult to draw”.

Gullop World Poll Questions: Did you experience happiness during a lot of the day yesterday? World Value Survey: Taking all things together, would you say you are: 1. Very happy; 2. Quite happy; 3. Not very happy; 4. Not at all happy. National Survey of Families and Households: Taking all things together, would you say you are: 1 = Very unhappy to 7 = very happy.

In contrast to studies cited in this study using longitudinal data sets, Easterlin (2003) used a cohort study to argue that there is no selection effect. He noted that marriage rate dramatically rises from late teens to their late 20 s, and that the happiness level also rises during the same part of lifespan. If there is a selection effect, then the average happiness of the singles left in the same cohorts should decline. But it did not decline.

According to Taiwan Social Development Trend Survey (2002), 83.94% unmarried adults live with their parents. Of unmarried adults who did not live with their parents, most of them migrated to metropolitan areas for a job. This survey discontinued after 2002, but today the majority of unmarried Taiwanese adults still live with their parents.

References

Argyle, M. (2003). Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 353–373). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Arrosa, M. L., & Gandelman, N. (2016). Happiness decomposition: Female optimism. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 731–756.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 133–153.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2016). Antidepressants and age: A new form of evidence for U-shaped well-being through life. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 127, 46–58.

Cheng, T. C., Powdthavee, N., & Oswald, A. J. (2017). Longitudinal evidence for a midlife nadir in human well-being: Results from four data sets. The Economic Journal, 127(599), 126–142.

Clark, A. (2007). Born to be mild? Cohort effects don’t (fully) explain why well-being is U-shaped in age. IZA DP No. 3170.

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118(529), F222–F243.

Demidenko, E. (2004). Mixed models: Theory and applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. The American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341.

Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, E. M., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 419–436.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176–11183.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Diminishing marginal utility of income? Caveat emptor. Social Indicators Research, 70(3), 243–255.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Frijters, P., Johnston, D. W., & Shields, M. A. (2011). Life satisfaction dynamics with quarterly life event data. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(1), 190–211.

Gove, W. R. (1973). Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology, 79(1), 45–67.

Gove, W. R., Hughes, M., & Style, C. B. (1983). Does marriage have positive effects on the psychological well-being of the individual? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(2), 122–131.

Green, D. P., Kim, S. Y., & Yoon, D. H. (2001). Dirty pool. International Organization, 55(2), 441–468.

Guven, C., Senik, C., & Stichnoth, H. (2012). You can’t be happier than your wife. Happiness gaps and divorce. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82(1), 110–130.

Hao, L. (1996). Family structure, private transfers, and the economic well-being of families with children. Social Forces, 75(1), 269–292.

Kessler, R. C., & Essex, M. (1982). Marital status and depression: The importance of coping resources. Social Forces, 61(2), 484–507.

Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 75–79.

Lucas, R. E., & Clark, A. E. (2006). Do people really adapt to marriage? Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(4), 405–426.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 527–539.

Marks, N. F., & Lambert, J. D. (1998). Marital status continuity and change among young and midlife adults longitudinal effects on psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 19(6), 652–686.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 46, 69–85.

Musick, K., & Bumpass, L. (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 1–18.

Myers, D. G. (2003). Close relationships and quality of life. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 374–391). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Næss, S., Blekesaune, M., & Jakobsson, N. (2015). Marital transitions and life satisfaction: Evidence from longitudinal data from Norway. Acta Sociologica, 58(1), 63–78.

Pearlin, L. I., & Johnson, J. S. (1977). Marital status, life-strains and depression. American Sociological Review, 42(5), 704–715.

Qari, S. (2014). Marriage, adaptation and happiness: Are there long-lasting gains to marriage? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 50, 29–39.

Soons, J. P., Liefbroer, A. C., Kalmijn, M., & Johnson, D. (2009). The long-term consequences of relationship formation for subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1254–1270.

Stack, S., & Eshleman, J. R. (1998). Marital status and happiness: A 17-nation study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(2), 527–536.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 326–347.

Umberson, D. (1992). Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science and Medicine, 34(8), 907–917.

Waite, L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32(4), 483–507.

Waite, L., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are healthier, happier, and better-off financially. Westminster, MD: Broadway Books.

Wilson, C. M., & Oswald, A. J. (2005). How does marriage affect physical and psychological health? A survey of the longitudinal evidence. The Warwick Economics Research Paper Series, University of Warwick, Department of Economics.

Wood, W., Rhodes, N., & Whelan, M. (1989). Sex differences in positive well-being: A consideration of emotional style and marital status. Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 249.

Zimmermann, A. C., & Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and happiness in Germany. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 511–528.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Chen-Ling Yeh for her excellent assistance with the data collection and analyses. Financial support from Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology is acknowledged. Award Number: MOST 106-2410-H-031-003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, HL. Marriage and Happiness: Evidence from Taiwan. J Happiness Stud 20, 1843–1861 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0029-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0029-5