Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to discover what enables young people in Australia to create healthy relationships despite exposure to domestic violence (DV) in their families of origin during their formative years.

Method

Taking an ecological systems theory and mixed qualitative methods approach, a survey was designed to identify different factors that young people recalled as helpful when they were enduring DV as children and, later, as young adults. Two hundred and three young people aged 18–30 years completed the national online survey. In addition, to achieve richer insights and an understanding of the complexities in individual experiences, fourteen of the survey respondents then participated in in-depth life-history interviews.

Results

Although most participants believed they had been adversely affected by growing up in DV, empathetic family members and friends, achievements through school and sports, and gaining knowledge about DV and healthy relationships, often through social media, enabled many to distinguish the difference between healthy relationships and DV. These influences then affected how they approached partnership relationships as they matured.

Conclusion

Analysis of survey and interview data led us to consider that all strata of the ecosystem could, through applying prevention and early intervention strategies, support children and young people to identify and choose healthy relationships rather than accept prescriptive, pathologizing predictions for their future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As Alexander et al., writing about DV, note: “Intergenerational transmission is a highly influential and persuasive concept in the literature but is rarely critically examined” (2016, p4). Following this, Copp et al. (2019, p 1357) note that “it is intuitive to expect that individuals exposed to violence in the family of origin may internalize behavioral scripts for violence and adopt attitudes accepting of IPV”. Further, as Haselschwerdt et al. (2019) surmise: “researchers, practitioners, and policy makers alike often document family violence exposure as one of the strongest risk factors or predictors of later IPV (interpersonal violence) involvement” (p. 168). However, some research shows that while a number of children may accept DV as normal and go on to perpetrate or experience it in adulthood, others do not follow what has been referred to as a pattern of “intergenerational transmission of abuse” (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2023; Humphreys, 2007; Kitzmann et al., 2003).

Many children are adversely affected by living with DV (Finkelhor et al., 2015; Vu et al., 2016). However, we argue the idea of “intergenerational transmission of abuse” can be used in a universalistic way implying that further abuse is anticipated; this can result in a failure to consider other influences in children’s lives that could lead to more positive outcomes. The premise of “intergenerational transmission of abuse” undermines children and young people’s ability to see themselves as able to adapt with the help of certain supports in their environment (Katz, 2016).

The aims of the research study were, firstly, to generate new knowledge about young people’s experiences of growing up with DV. Secondly, to increase understanding about factors in the social context that help young people establish healthy relationships in adulthood. Thirdly, to identify systems and supports that may help young people form relationships that are free of violence and abuse in adulthood. Finally, the research sought to contribute to the development of informed preventive policy and practice that supports children and contributes to increased community safety. The objective was to inform policy and interdisciplinary practice so that a range of societal factors that can increase children and young people’s agency and decrease the likelihood of “intergenerational transmission of abuse” can be promoted.

Situating Children’s Experiences

DV is the repeated use of coercive and controlling behavior by one partner against another in an adult relationship with intent to limit, direct and shape their partner’s thoughts, feelings and actions (Stark & Hester (2019). Coercive and controlling tactics include physical and emotional abuse, threats and intimidation, isolation and entrapment, sexual abuse and exploitation as well as abuse of children (Bell & Flood, 2020).

DV is currently at epidemic proportions in many countries around the world with no indication that the number of cases is declining. Worldwide, 27% of women who have been in a relationship report that they have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by their partner. (WHO, 2021). In Australia, 23% of women and 7% of men experience violence at the hands of an intimate partner (ABS 2016). Moreover, 23% of women who experienced DV from an abusive partner had children in their care, with 59% reporting that violence had been witnessed by their children (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Whether exposed to incidents of physical violence or not, living with DV can negatively affect children’s wellbeing (Campo, 2015).

Outcomes of Growing up with DV

The effects of DV on children’s wellbeing and social development have been widely researched and documented (Barnes et al., 2022; Campo, 2015; Forke, 2019; Graham-Bermann et al., 2009; Øverlien, 2017). Further, it is recognised that children raised in DV can face psychosocial challenges and developmental hurdles because of their childhood experiences (Fellin et al., 2019). Campo (2015), for example, documents the effects of DV on children’s wellbeing and social development. Her study examines the international research assessing children’s exposure to DV, finding effects on children’s behaviour, schooling, cognitive development, and mental and physical wellbeing. This suggests that children who grow up in DV require attention in policy, practice and research, and it is noted that there is relatively little research that examines best responses to children exposed to DV.

A growing body of evidence indicates that some children who grow up with DV do not appear to be traumatised by their experiences. When looking at the effects of DV on children Humphreys (2007) found that 50% of children exposed to DV fare as well as other children. Further, Kitzmann et al. (2003), in their seminal meta-analytical review, analysed 118 studies of children exposed to DV and found that 33% of the children had wellbeing scores comparable with, or better than, other children. Children’s ages, gender, coping abilities and supports in the societal context have been found to influence the outcomes associated with growing up in DV (Barnes et al., 2022; Clements et al., 2008; Yule et al., 2019). Research indicates that the extent to which children are able to cope with DV is linked to their mothers’ capacity to maintain close relationships and protect their children as well as they can (Buchanan, 2018; Winfield et al., 2023). Further, research by O’Brien et al. (2013) found that the potential threat to a child’s immediate and long-term wellbeing can be reduced by them establishing a safe place and a supportive relationship outside the family home. Extended family, school achievement and social supports may also positively impact on children’s coping capacities (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2023; Humphreys, 2007).

Despite growing understanding of the complex influences on children raised in homes where there is DV, there is some evidence that children raised in DV are at higher risk of perpetrating or becoming victims of violence themselves in their own adult relationships (Copp et al., 2019). There is a body of research that suggests boys exposed to DV in their family learn from their fathers’ abusive behaviours, and girls growing up with DV learn from their mothers to be passive victims of abuse (Hou et al., 2016; Abbassi & Aslinia, 2010; Cochran et al., 2017;). We acknowledge that growing up with DV may increase the risk of perpetrating or becoming a victim of DV, but believe that ‘intergenerational transmission” is not inevitable.

In extensively cited research (1123 citations), Stith and colleagues (2000) conducted a meta-analysis of 39 published and unpublished studies and found that “there is a weak-to-moderate relationship between growing up in an abusive family and becoming involved in a violent marital relationship.” (p.640). A more recent meta-analysis of studies concerning the intergenerational transmission of violence found minimal correlation between exposure to DV in childhood and involvement with DV later in adulthood (Smith-Marek et al., 2015). This research identifies nuances and complexities through influences in the immediate environment. Another methodological review of the research into intergenerational transmission of violence by Haselschwerdt et al. (2019) found there was too much variability and a lack of complexity in the existing research.

The three studies cited above look for correlations between growing up with DV and becoming a perpetrator or a victim in adult life. None ask about factors that may assist children who experience DV in childhood to achieve healthy adult partner relationships. Elsewhere, a quantitative meta-analysis by Yule et al. (2019, p 406) found that “self-regulation, family support, school support, and peer support” afforded protective factors and increased resilience for children who experienced violence. However, this study concerned child abuse and community violence as well as DV. To understand the factors that enable individuals to form partner relationships free of violence, it is necessary to explore how people who have grown up in DV have managed to forge healthy partner relationships in their adult lives. This helps us understand the social contexts and complexities that can lead to young people rejecting DV despite their childhood experiences. The study presented here explores the perceptions and experiences of young people who grew up with DV and now strive for relationships they consider to be healthy. This study questions the prevalence of intergenerational transmission of abuse and increases understanding with a view to informing prevention initiatives, policy and practice approaches that can enhance young people’s ability to reject DV.

Theoretical Framework

This research utilized Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory to look at factors in the social environment that enable young people who have grown up in DV to forge positive relationships in adulthood. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory describes society as a systemic context comprising multiple strata, each of which impacts on children. The microsystem includes the immediate family living with the child, groups, and organizations such as school, peers and community groups; the mesosystem refers to the connections between the elements of society in direct contact with the child; the exosystem comprises indirect environments, for example health and education systems, that impact on the child; the macrosystem comprises ‘‘broad cultural values and belief systems’’ (Lawson, 2012 p. 19). The final stratum is the chronosystem, which represents the process of time, development and changes across time. In this study, factors in the ecosystem that may influence choices about relationships as an adult are examined, with a focus on how elements of the ecosystem offer diverse options for people who grow up with DV. Tangible practices which offer support are then identified.

Methods

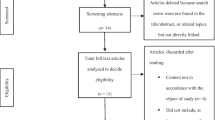

The research used a mixed methods qualitative design of online survey followed by life history interviews to investigate how social contexts in the ecosystem shape the lived experiences of children growing up in DV, and their capacities to form adult partner relationships free from violence. In stage one of the study, a national online survey questionnaire was designed and implemented to collect demographic and qualitative data from young individuals (18–30) who self-identified as having experienced DV as children. Many studies now recognize young adulthood as extending beyond 25 years of age (see, for example, Sexton-Dhamu et al., 2021) This is due to a prolonging of the period of social development (Qu, 2019; Wilkins et al., 2021). The survey was advertised on social media platforms including Facebook and Instagram, as well as through physical flyers posted around university campuses. Participants either clicked on the survey link or scanned a QR code which opened the survey for them to complete. Overall, 323 people opened the survey link, with 203 young individuals completing it. The sample size enabled us to recruit a diverse sample of participants.

The survey identified aspects of childhood experiences while enduring DV, and the influences which informed participants’ perspectives on their adult partner relationships. Data collected in the online survey provided a broad picture of participants’ experiences of childhoods that involved abuse by one parent against the other and its impact on their lives. The survey specifically explored the positive effects of different interpersonal relationships in the microsystem, pursuits and hobbies, the role of extended family and community support. The role of social systems in the exosystem such as schools, religious bodies, sports, arts and leisure organizations that affect children and young people were also the subject of enquiry. The impact of media was identified to illustrate the influence of certain discourses about healthy and unhealthy partner relationships in the mesosystem.

Selection criteria required that participants: were between 18 and 30 years of age; lived in Australia and were competent in English;. Demographic information was collected about gender and sexual identification, age, relationship status, country of birth, years in Australia, ethnicity/cultural background, religion, income, employment status and level of education, sexual orientation and disability, plus location (see Table 1). Ethics approval was granted by the Human Ethics Research Committee, University of South Australia. Survey questions were piloted with a small group of students from the University of South Australia who had experienced DV as children. The survey was adjusted in accordance with the students’ feedback.

A web page was set up specifically for the research project on the University South Australia’s Safe Relationships and Communities Research Group (SRC) site. The online survey, once uploaded, was promoted through general Facebook advertising, through the Facebook and Twitter pages of health and social service agencies, and through flyers displayed across university campuses and community venues. These recruitment methods facilitated a population-based sample.

The qualitative survey data was analyzed through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) using an inductive approach to the identification of themes. Data analysis was managed with NVivo software. Thematic analysis involved searching for commonalities and differences in individual experiences (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To prepare for Stage 2 of the study, we drew on findings from the analysis of survey data to design a semi-structured, in-depth interview guide. When participants completed the online survey, they were asked whether they would like to volunteer for an interview and, if so, to provide their contact details.

In Stage 2 of the research study, fourteen survey participants who had indicated that they would like to be interviewed were invited to participate in face-to-face interviews conducted by a member of the research team. Interview participants were selected by the research team to represent diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures, metropolitan and rural locations, gender, and sexualities. The purpose of the interviews was to gain deeper insights into complex interconnected experiences over time, explore participants adult experiences of partner relationships and factors that participants believed enabled them to form healthy adult partner relationships. The nature of individuals’ current partner relationships and how they were seen to differ from DV was explored. Interview participants were also asked to suggest ideas for services and preventative strategies to help support children and young people who grow up with DV to forge positive partner relationships in adulthood.

Life history interviews that prompt subjective accounts of participants lives in their own words (Olive, 2014) through question and answer were utilized. This approach to interviewing helped the interviewer and the participant to explore how experiences and connections shaped individuals’ choices and actions and accessed complex narratives about participants’ perceptions, and how these evolve over time (Davies et al., 2018). While taking a life history approach we asked participants to expand on their survey responses and used prompt questions to encourage the sharing of narratives in relation to their personal chronosystem. Interviews included the construction of ecomaps (Manja et al., 2021), where, using A3 paper and fibre tip pens, the participant placed their given name in a circle in the center of the paper. Circles surrounding their central circle are then drawn to represent individuals, networks, organizations and systems that were of importance to the participant as they were growing up (Crawford et al., 2016). The inclusion of representations is within the participants control and provides a visual representation of factors influencing their relational development.

All young people who were interviewed received an honorarium of a $50 gift voucher. Transcripts from the interviews were analysed through narrative analysis, which attends to both the themes as they unfold within individual narratives as well as across narratives (Riessman, 2008). Data was added to the Nvivo-stored analysis from the survey. Interview participants were allocated pseudonyms and these pseudonyms are used in the findings presented here.

Participants

85% of the survey respondents were female, 12% male and 3% identified as either non-binary or transgender. More than half (57%) identified as heterosexual and 43% identified as LGBTQIA+. A large proportion (86%) of participants were Australian born, 6% Aboriginal Australian, with the rest born in diverse locations around the world. Aboriginal young people’s perspective is the subject of a separate paper, currently under review. More than three quarters (77%) of participants identified as non-religious, 11% as Christian and others as Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu and other. Participants were from all states and territories in Australia, with 64% living in cities while others lived in regional centers, country towns and remote areas. Over half the participants (53%) had lived with DV since their early years (0–5) and 62% had lived with DV for over 11 years. In 71% of cases, the main abuser was their father or stepfather, while in 22% of cases, their mother or stepmother was identified as the main perpetrator of abuse. Table 1 outlines the demographics of the survey and interview participants in greater detail.

Findings

Young People’s Experience of Growing up with DV

Most (94%) of the survey respondents in this study believed that they had been adversely affected by their childhood experiences of DV, and felt that their emotional, psychological, mental and/or physical health had been compromised. Only 6% of participants thought they were not harmed by living with DV. Most participants (94%) also believed that their attitudes to, and beliefs about, partner relationships were affected by enduring DV as children.

When participants were asked about the long-term effects of living with DV as children, many spoke about lack of trust, emotional and psychological harm. These effects were seen across genders and age groups. As one participant stated: “I never believed I was good enough. I always thought I would fail” (Survey respondent 103, female, age 24–30), while another explained:

It’s hard to know who to trust because I learned first-hand how two faced people can be. My father was fake to those outside the house. (survey respondent 7, male, aged 18–23)

Many participants described childhoods where they felt isolated because of DV. Their home life led to them feeling different from other children, with 71% reporting few supports at school. For example, one survey respondent said:

It made me struggle in school a lot. I had few friends. I slept in class because I couldn’t sleep at home. I didn’t trust teachers or any adults. My grades suffered. (Survey respondent 181, non-binary, age 24–30)

Several participants remembered how the effects of living with DV left them unable to focus on learning. One survey respondent said, “I went from a straight A student to failing, wagging, getting into trouble … It was the only way I had to vent.” (Survey respondent 99, female, age 24–30), with another stating their experience at home ‘severely impacted my academic capacity’ (survey respondent 15, male, aged 24–30). Respondents variously described being distressed, tired or overwhelmed by concerns about the situation at home. These experiences were again similar across genders and ages, with most participants indicating a negative impact on their schooling. Some mentioned missing days at school because of tiredness and stress:

Stress induced illnesses resulted in missing days of school and difficulty engaging with peers (physically fatigued and emotionally exhausted)” (Survey respondent 62, female, age 24–30).

It shifted my focus, I didn’t want it to impact my education, but it did” (survey respondent 133, male, aged 18–23).

Some participants attributed being bullied at school to the effects of DV on their self-esteem and self-worth. As one respondent stated: “I could not focus, was bullied at home and school” (Survey respondent 88, male, age 24–30).

Occasionally, a respondent identified that living with DV led to seeing school as an escape where they were able to immerse themselves in study and do well academically. For instance: “I think I was good at school it was an escape from home, so I dedicated a lot of time to my studies” (Survey respondent 217, female, age 18–23). One interviewee said:

School was also a very positive aspect of my life and a coping mechanism. I performed well academically and had wonderful friends and teachers which helped me to feel positive and valued. School was my safest place! (Fay, female, age 24–30).

This participant gained the support of teachers and formed a positive self-identity through their achievements, despite the struggles to attend school.

Supportive Relationships

Respondents and interview participants indicated that if there was at least one person who connected with them - whether it was a family member, teacher, a friend who had been through similar experiences, or a friend’s parents stepping in to validate and appreciate them - they remembered that supportive relationship as helping them to develop understanding of healthy relationships. Several also identified that supportive relationships within their microsystem helped them to differentiate between DV and healthy relationships through the warmth and care they felt from those people. Nearly half the survey respondents (49%) felt their relationships with their non-abusive caregiver sustained a belief in others and their ability to connect; this percentage was skewed slightly to female participants. For example: “My mum was my safe person. I could talk to her about anything. She allowed me to safely talk about my feelings” (Lisa, female, aged 18–23). Another participant stated: “My father was very empathetic and helped me to rationalize my feelings” (survey respondent 135, male, aged 18–23).

Within the immediate family, siblings were also seen as a support by more than half of participants (57%) who shared experiences and were able to comfort each other, a percentage which was again skewed towards female participants. Other participants identified that, although relationships with siblings had been strained during childhood because of living with DV, sibling relationships improved after adolescence leading to healthy adult relationships where siblings could share their perspectives on their earlier experiences. As one participant stated: ‘Me and my siblings talk about everything that happened with my Dad now that we’re older and can process everything’ (survey respondent 138, female, aged 18–23).

Outside the immediate family, supportive grandparents, particularly grandmothers, played an important role for many children. For example, one respondent wrote, “My grandmother made me feel safe” (Survey respondent 205, female, age 24–30). Healthy relationships between and with extended family members were also seen to demonstrate an alternative to the DV children were experiencing at home:

My mum’s parents, they were like second parents and gave unconditional love and support. Their relationship is how I view my relationships should be, mutual with good communication, openness and honesty. (Survey respondent 209, female, age 18–23)

41% of participants had supportive relationships in their extended family and 9% escaped from DV at home by going to stay with extended family:

My mum’s immediate family (my aunts, uncles, grandparents) have always been supportive of me. They would let me stay a few nights at their houses when I couldn’t handle being around my stepdad anymore. They listened to me and believed me when I detailed the abuse to them, when other adults would belittle me or assume I was lying (Survey respondent 287, female, age 24–30).

The ability to find support from extended family members was also true for most gender and sexually diverse participants. However, for some whose families were not accepting of their identities, they sought help elsewhere finding connection in the wider LGBTQIA + community provided a much-needed source of support:

I was in a suicide prevention group for LGBTIAQP + people. They had a peer worker and a social worker there. Over the years this person would support me through some of the worst PTSD struggles and it was in this community center, that I learnt basic social skills, relation skills, emotional regulation skills in a safe environment (survey respondent 186, non-binary, aged 24–30).

Less than half (43%) of respondents identified as having supportive friends, and this was again seen more often among female participants, with those aged 24–30 indicating having supportive friends more often. A lack of supportive friendships was often seen as resulting from the effects of the situation at home, and pressure to keep the violence secret. However, when supportive friends were available to them, participants valued these relationships:

I again didn’t tell many friends the whole story and I was finishing year 12 at the time so my close friends were supportive in helping me study for exams and getting me through in that respect. Now I’m more open with current (and some of the same) friends who are a great listening ear and help out if I’m experiencing repercussions of the 18 years of abuse (Survey respondent 302, female, age 24–30).

My friend supported me emotionally through high school and was one of the only people I could spend time with and laugh with; he remains supportive in this way. (Survey respondent 305, female, age 24–30)

In their microsystems, some survey respondents and interview participants had friends who had similar experiences and they were able to talk with them about what was happening at home: “From around 14 I made a close friend from the scout group I joined at that time. They just seemed to ‘get it’ when we talked about things, and they also grew up with DV at home” (survey respondent 250, female, age 24–30). This was something that many, as children, thought they could not do with friends in general as other children would not understand: ‘I had two friends who were also from families experiencing DV. We got each other in ways other friends couldn’t understand’ (survey respondent, 7, male, aged 18–23).

Friends who did not share experiences of living with DV were, however, valued in other ways. When participants had childhood friendships, they sometimes observed and noted healthy relationships in their friends’ families. When participants visited friends, had sleep-overs or spent extended time with their friend’s family, this afforded them a safe space that was appreciated as a source of comfort and provided an alternative model of a home environment: “I used to spend a lot of time at friends’ houses. Their parents provided me with a lot of care and security, and I started learning through that that what I was experiencing wasn’t normal” (survey respondent 196, female, age 24–30). At times, when they were included in day-to-day life of other families, participants felt valued.

Individual teachers, school counsellors, neighbors, church members and group leaders were sometimes described as providing support and validation for participants, though these seemed to be more likely sources of support for female participants:

Teachers and professors believed in me and told me I was capable and let me turn in assignments late when I was struggling the most. An administrator at my university provided housing for me when I was homeless (survey respondent 305, female, aged 24–30).

Our next-door neighbor, she had three children of her own – I would often stay with them when things weren’t good at home or when mum was in hospital. She was like a second mother (survey respondent 72, female, aged 24–30).

When supportive adults indicated that they knew of the situation at home and put time into being a comforting presence, this was seen as invaluable.

Out of home Activities

Apart from the comfort and support of others, 61% of participants recounted activities that offered some escape from the trials of home life. Sports, hobbies, and group activities were valued as time spent focusing on something other than the problems at home, and importantly, as providing time and physical space away from the home: ‘being part of a community increased my self-esteem and confidence building in relationships’ (survey respondent 254, female, 18–23). Most interview participants also recounted activities outside of the home as useful: “for me involvement in afterschool activities was hugely supportive in again seeing different kinds of people and being out of the abusive home which is just a relief” (Sarah, female, aged 24–30). Pursuits that provided enjoyment and relief included sports ranging from rugby to netball, music lessons, art, dance, drama and church youth groups. Participants described activities as “an outlet”; “contact with the outside world”; and “something to look forward to”. A few male participants indicated that playing sport provided a socially acceptable way for them to deal with negative feelings: ‘it became an outlet to release my frustrations in a controlled environment which was rugby league’ (survey respondent 89, male, aged 24–30).

For participants who achieved success in out of home pursuits, this helped to raise their self-worth and negate some of the hopelessness instilled at home when an abusive parent undermined or ridiculed their abilities: “It gives some form of validation when people compliment it…it makes me feel like, I guess it makes me feel like something, I am someone, like I have a reason to be here” (Jason, male, aged 24–30). and “They [activities] gave me something I was good at. A place where I could go and people valued me” (survey respondent 196, female, aged 24–30). However, 39% of participants were either not allowed to take part in out of school activities or the effects of living with DV on their self-worth or ability to socialize left them unable to participate. As one participant stated: ‘I didn’t have the confidence and was afraid I would fail team-mates and get in trouble’ (survey respondent 135, male, aged 18–23).

Education and in-school Support

Only 5% of survey participants remembered formal education classes about relationships. In interviews, some said that they thought if they had some education about healthy relationships, as well as all aspects of DV, they might have recognized earlier that what they were experiencing at home was not healthy:

Guess like a little bit more education around it because I think during school I didn’t, there was nothing about DV or where you can get help from. So I had to go and find that myself. So it would be good if there was something about that in school (Jason, male, aged 24–30).

Although formal teaching about healthy relationships was not available to most participants, when a teacher or school counsellor took an interest in them, this was remembered as providing an illustration of a supportive relationship. As one participant recalled, his art teacher helped him to feel comforted and safe through pastoral care:

Whenever I had problems at home I could go to school and escape the conflict that I was having at home and yeah like because I had this one teacher in year 7 I think, and like she just, because I had a conversation with her and that conversation kind of changed my whole perspective and everything about what I can achieve. Like she really just, I really believe in you and she said I am proud of you which is the first time I have ever heard someone say I am proud of you. So, like that was just great. Having her throughout my education pushed me (Jason, male, aged 24–30).

Teachers who helped the young person to achieve and feel valued were appreciated:

My senior math teacher in high school, by then knew that things at home weren’t great and that I worked quite a lot so I used to catch the early bus to school and get there 7.30 and she would open up one of the classrooms and do her classroom planning so I could sit there and do homework with the heating on, and I know that sounds like a really small thing, but this was really, really important to me…the idea that somebody got to school half an hour [early] every day and instead of talking with her friends in the teacher’s lounge, just came and sat in the room with me so I could have heating. We never talked about any of it, she never really talked to me at all, but just to have someone who sat there in a warm room’ (Ann, female, aged 24–30).

To some extent, it was recognized that teachers and counsellors were limited in what they could do but participants particularly appreciated teachers and counsellors who were prepared to listen. One respondent said, “My English teacher. She was mid 20s and had been through an abusive past. She would counsel me, probably the most supported I felt when I would speak to her about my home life” (survey respondent 285, female, aged 18–23).

Counselling and Support Groups

When asked if they received counselling as a child, 45% of survey participants indicated that they did, with the majority of these participants being female and no discernable differences in age groups. Others stated the need for counselling was not recognized as necessary or their parents would not have allowed them to talk to a counsellor. From the responses of those who had received counselling as children, few recalled counsellors who were knowledgeable about DV or understood the effects of living with DV on children. However, one interview participant recalled “for a short period in my early childhood when I was probably early school age some social workers in my life helped me build self that was not rooted in violence” (Sarah, female, aged 24–30).

Receiving information about the breadth of behaviors defined as DV was particularly appreciated by some participants and helped them understand as children that social, sexual, psychological, and financial abuse, as well as physically hurting a partner, were not acceptable or usual interactions in families.

Only 3% of participants had access to groups which addressed DV, yet 73% felt participation in a group where they could meet with others who had similar experiences would have been useful: ‘So kids are aware they’re not alone and not forgotten or unrecognized’ (survey respondent 28, female, aged 24–30). Interestingly, when participants were able to make their own choices as young adults, 77% chose to have counselling, with about half of the male, two-thirds of female, and over half of the gender and sexually diverse participants indicating they had chosen this as adults. Most described their experiences of counselling as ‘useful’, and ‘helpful’ when they found a practitioner they trusted: ‘Helped a bit to be heard without prejudice’ (survey respondent 132, male, aged 24–30). An interview participant also suggested: “I’ve had a lot of therapy to work on my shame and fear because I, as I’ve come to accept from therapy, realistically don’t have much in common with my dad at all, especially the abusive stuff” (Sarah, female, aged 24–30).

The Importance of mass Media

As conveyors of social and cultural values, television and film were seen as helpful by 47% of participants, the vast majority of whom were female. These participants thought mass media was important in providing information about healthy relationships and showing alternatives to DV. In interviews, participants talked about media challenging or maintaining harmful ideas around DV: “TV was one of the ways I realized my life was not normal and I was able to see what a good loving relationship could be” (Survey respondent 99, female, age 24–30).

Over one third of participants (34%) reported first being able to name their experiences because of engagement with social media, including starting to recognize abuse and feeling acknowledged. For example, one participant, referring to you-tube, said: “Some of the material on DV was helpful to educate and understand what was happening” (survey respondent 75, female, aged 24–30). Facebook was mentioned as most valuable in terms of participants connecting to people with similar backgrounds, finding that they were not alone and enabling them to talk to others about their experiences:

Solidarity feels good. I have that with Facebook groups (survey respondent 211, female, aged 24–30).

I would say social media to an extent has helped me – being able to find I guess services through there and also hearing other people’s stories about how they – like finding people that I can relate to, so not being alone (Jason, male, aged 24–30).

Reflecting on Their own Adult Relationships

We defined a healthy relationship as one where there is mutual respect, shared decision-making and choice. Not all respondents identified as having healthy partner relationships; some avoided relationships, others identified past relationships when their partner abused them and were working towards healthy relationships. However, all completed the survey because they felt they had something to add about how healthy partner relationships can be developed.

In survey responses, many reflected on how growing up in DV affected their attitudes to adult partner relationships. During interviews, participants were asked about their own adult partner relationships. In both, many participants were clear about what they did and did not want in their own partner relationships. Some feared that they would repeat abusive patterns and become victims or perpetrators in their own intimate relationships. Participants were thoughtful and reflective about their experiences of living with DV and wanting to ensure that they did not replicate their parents’ roles. One survey respondent, for example, stated when discussing seeing a psychologist as an adult: ‘It helped reassure me that I can choose not to be like my father because I was always worried about that’ (survey respondent 141, male, aged 18–23). Many identified that, because of growing up with DV, trust was a barrier to creating relationships for themselves:

It’s that whole thing where it’s like I can’t tell you anything because you might use it against me and or it might end up badly or you might end up hurting my feelings and I don’t want to put myself in that situation (Jason, male, aged 24–30).

I don’t trust men. I see red flags with anyone who wants a genuine relationship. I don’t trust that they won’t abuse me (survey participant 14, female, aged 24–30).

Some participants were vigilant about their own behavior and the behavior of others. Through education and time, they had become clear about the range of behaviors that constitute DV and clear that abuse in any form is harmful. One interview participant spoke about looking for two-way respect. Another described experiencing abuse in an earlier relationship, but being able to identify what was happening and ending the relationship:

A relationship where they’re, where decisions are made together with each other’s needs, wants, goals in mind I think is really, really important to me as a signifier as something that is healthy…respect is really key, not just having respect but showing respect particularly in front of others (Ann, female, aged 24–30).

It’s kind of like I’m using the blueprint of watching my parents’ failed marriage and relationship and that abusive relationship I was in for years, as examples of what not to do and what kind of behavior not to get back into… (Rosa, female, aged 24–30).

Informing Preventative Policy and Practice

In survey responses and interviews, participants were asked their opinion about what would help children who grew up with DV to be able to form healthy partner relationships as adults. Several identified change at the macro level which might result in societal encouragement of all people to understand and value respect, and this recognition was common across genders and age groups:

I think it comes down to things like power and control and that. Look if we’re just being completely objective as well, yes domestic abuse affects everyone and it disproportionately affects women, and so with perpetrators mainly being men, and so I think societal ideas around masculinity has a lot do with that and also the way in which we raise our children I suppose, to contribute to things like rape culture, like just again based on understandings of gender. You know boys will be boys or all those sort of things. (Fay, female, aged 24–30)

Let’s normalize the fact that people go through this, like actually say, I survived DV, I am in therapy. I perpetrated DV, I am in therapy because this is what happened to me. Here’s the website where you can access literally every resource under the sun, that would help anybody with any number of things…at a societal level that’s what needs to happen. (Dave, transgender male, aged 24–30)

Build healthy relationships into the school curriculum, make youth dv support organizations more visible and accessible. (survey respondent 255, female, aged 24–30)

Dave made the further point that resources need to take into consideration diversity in cultural background, language, gender and sexualities, in essence that: ‘They need to be informed by intersectionality’. Within these responses, knowledge-sharing was seen as important with schools, media, communities, counsellors and group facilitators who were knowledgeable about DV and coercive control considered paramount. Encouragement to think about what was required of them as well as of others was seen as important to enable young people who had grown up with DV to create adult partnerships they would choose rather than one that was predestined for them.

Discussion

Our research study set out to explore what helps young people in Australia create healthy partner relationships and reject DV based on the experiences of young people who grew up experiencing DV perpetrated by one parent against the other. The young people who participated demonstrated awareness, thoughtfulness and self-reflection regarding their early experiences. The themes extrapolated from participant responses to the national survey and follow-up interviews identified positive influences at every level of the ecosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). We aimed to identify how these forces could be enhanced so that children and young people are encouraged to make choices that lead to them achieving healthy partner relationships for themselves.

Helping Children to Connect in the Microsystem

Prior research has indicated that, although there may be increased risk of perpetrating or being subjected to DV (Hou et al., 2016; Abbassi & Aslinia, 2010; Cochran et al., 2017). if there was violence perpetrated by one parent against the other in a child’s family of origin, future involvement in DV is not inevitable. Yule et al. (2019) and Smith-Marek et al. (2015) indicate from their research that there are supports in the microsystem that can positively affect the outcomes for children raised with violence perpetrated by fathers against mothers. Following their research we sought to broaden and deepen understanding by consulting young people about all levels of the ecosystem that may influence their choices. Children and young people’s supportive relationships varied but being included in the lives of supportive extended family, neighbors, friends and families of friends helped them to feel valued and exposed them to relationships that contrasted with their experiences of DV at home. A gender difference was evident here with female participants being more likely to indicate that they had external sources of support. One possibility is that gender socialization limits the expressions of emotion and vulnerability that males feel they are able to show (Connell, 2005). This may make them less likely to seek support from external sources. Social ideas about masculinity in addition to the presence of a controlling parental figure, may explain this result. Many gender and sexually diverse participants indicated that they felt supported in their microsystems, but some mentioned finding their support within the LGBTIQA + community.

Easily accessible information at a community level could encourage more community members to think about the issues children are presented with, understand their needs and the part connections with others play in mitigating children’s adverse home situations. From the data provided by the young people who participated we posit that information about how children and young people learn to build trust in partner relationships, recognize opportunities for connection and sharing ways to support, could assist children and young people living in DV (Durlak et al., 2010; Greenberg et al., 2017). Learning social skills, including befriending skills, from concerned others who may ameliorate the effects of DV at home.

Support in the Mesosystem

Similarly, it is evident that teachers, school counselors, organizers of clubs and groups, service providers and all adults formally involved in children and young people’s lives could extend support if they better understood the parameters of DV, and the effects of DV on children and young people. The importance of school and extra curricula activities for children and young people experiencing DV could be addressed through action at a whole of population level. Simultaneously, access to appropriate, well-informed counselling and groups for children and young people should be more widely available, resourced, and designed so that children and young people can attend without fears for their safety (Clarke & Wydall, 2010). In this way more children and young people can be given the tools to assist them in addressing any occurrence of low confidence and self-esteem which may impact their involvement in activities (Durlak et al., 2010). Potentially, attention may also need to be paid to the use of these activities as an outlet for frustration, particularly for young males, perhaps with role models demonstrating and encouraging emotion regulation.

Currently, support for families and children is crisis driven in the DV and child protection spaces (Humphreys, 2007; Zannettina & McLaren, 2014), and what is offered in the health area is sparse and potentially pathologizing in the child and adolescent mental health area (Arigliani et al., 2022). In contrast, what our participants have indicated helped, or would have helped, are services which understand, listen and support them to exercise agency in their lives (Katz, 2016). Such is the approach summarized in Morris et al., 2020 article which outlines attitudes that bolster children’s agency and abilities, including recognizing and acknowledging children’s abilities in utilizing support systems and co-constructing resiliency within the family (see also Winfield et al., 2023). Indications that this would have been helpful were common amongst participants of all genders and both age groups.

Pivoting the Exosystem to Prevention and Early Intervention

At the exosystems level governments, policy makers and multidisciplinary health and social service organizations can pivot to prevention through focusing on the strengths of young people, raising awareness through education campaigns, the provision of training and resources, and information sharing. Research with international experts and young people by Stanley et al. (2017), for example, examined media campaigns targeting young people. Results of this research highlighted the need for authenticity, narrative and content developed by young people and, indicated that young people should be involved in creating and delivering campaigns.

Our findings highlight that media plays an important role in education and information sharing for children and young people, and the value of connection through social media specifically requires recognition and support. One recent example of an organization harnessing media to support young people is the ‘Beyond DV’ (https://www.beyonddv.org.au/) organization creating a Teen Relationship App to help young people understand what healthy/unhealthy relationships look like. Such initiatives should be widely promoted through all parts of the mesosystem and exosystem.

To extend these supportive influences into the lives of children who grow up in DV, knowledge and understanding is needed in all sectors of society. As Butler et al. (2022) found in a study which focused more generally on the mental wellbeing of children and adolescents, multiple sources of support provide a cumulative effect on increasing wellbeing. From the responses given by our young participants we believe that similar outcomes could be expected for children who grow up with DV. By increased exposure to alternatives to abuse, children can grow to see themselves as able to create healthy relationships; to achieve this knowledge, the constituents and effects of DV and the elements that underpin healthy relationships must be broadly understood, and action at every level of the ecosystem is required.

Adapting with the Chronosystem

Finally, across the chronosystem, as children and young people grow into adulthood, different experiences and types of support may impact positively at different stages (Lawson, 2012). As children grow into teenagers, for example, and are more able and likely to engage with information on social media, online support groups may provide a positive way for young people to feel validated and understood, to garner knowledge and be empowered (Goodyear et al., 2019; Walrave et al., 2016). Research with young people is required to identify strategies which suit different stages of development. Further, as Stanley et al. (2017) suggest, materials should be designed for specific groups of children and young people: for example, those with disabilities, black, minority ethnic and refugee groups, and young people with diverse genders and sexualities.

Recommendations for Preventative Policy and Practice

Based on the findings, we posit that if preventive support and early intervention was available later relationship difficulties could be avoided. The range of strategies proposed above reflect an ecosystem’s approach which identifies elements to enhance each level of the system. We suggest prevention and early intervention provides the answers that can increase young people’s ability to create healthy relationships for themselves. Prevention targets groups of individuals, taking a broad-brush population approach that addresses social and gender norms (Kindig, 2007). Rather than solely focusing on intervening when crises occur, or labelling children as damaged by living with DV, a multidimensional preventive response could target every stratum of the ecosystem and ensure that children are exposed to understandings of healthy relationships as they grow. This would include public awareness campaigns targeting broad social attitudes, targeting all strata of society can ensure that the broader population is able to support children despite the circumstances in which they develop (Higgins, 2014). With regard to early intervention, investment to extend professional knowledge and skills in this area could ensure more children can access appropriately supportive services earlier. Access to appropriate services, including groups for children who are living with DV where they are able to have their voices heard, could help them to see themselves as having agency from an earlier age.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Despite every effort to recruit young men to this study we found, as in previous studies (Author 2015; Law, 2019), that male participants were in the minority. We would welcome research that devises strategies which successfully target young men. Future research may then focus specifically on a deep analysis of factors which helped young men to reject DV and choose to interact with respect and equality in their relationships.

Being a broad-based study which looked for a wide range of factors influencing children and young people, this research elucidated minimal information about relationships between siblings raised together when DV was a factor. Further study which looked at helpful aspects of relationships between siblings of both genders would further our understanding of how siblings can support each other over time. Similarly, the support of friendships over time and how they adapted in the chronosystem may be a valuable study. Although the majority of young people who participated in the study described here did not have access to counselling or groups for children affected by DV most felt that counselling, or groups in the company of other children who shared their experience, would have been helpful. We therefore suggest that research into what young people would find effective regarding services of this nature would be useful.

The study described here was qualitative research. Future research opportunities in the area of quantitative research may look at protective factors utilizing a random population-based sample to facilitate generalization for prevention initiatives.

Conclusion

Positive change can be acquired for more children by supporting them and extending endorsement to all who play a part in showing them that they are valued, and not predestined to recreate their parents’ relationship. To do this, changes in the ecosystem can ensure that children who grow up in DV are exposed to what comprises a healthy relationship. Through broad friendship and relationships in community, education, encouragement to participate in activities, positive role models in media and utilizing social media to share salient information and encourage healthy connections with others, children learn alternatives to DV.

Overall, there needs to be recognition that children and young people who grow up in DV are influenced by others and by other factors at all levels of the ecosystem. To support them, we need to stop pathologizing them. By applying prevention and early intervention approaches to address the issues for children raised in DV we can encourage their growth into adults able to make healthy choices regarding their relationships now and in the future. Further, greater comprehensive support through prevention and early intervention could help to minimize the high incidence of DV in the future.

References

Abbassi, A., & Aslinia, S. (2010). Family Violence, Trauma and Social Learning Theory. Journal of Professional Counseling Practice Theory & Research, 38(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2010.12033863.

Alexander, J. H., Callaghan, J. E., Fellin, L. C., & Sixsmith, J. (2016). Children’s corporeal agency and use of space in situations of DV. Geographies of children and Young People. Play, recreation, Health and well being. Springer.

Arigliani, E., Aricò, M., Cavalli, G., Aceti, F., Sogos, C., Romani, M., & Ferrara, M. (2022). Feasibility of screening programs for domestic violence in pediatric and child and adolescent mental health services: A literature review. Brain Sciences, 12(9), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12091235.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (ABS) (2006). Personal safety survey. viewed May 20, https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4906.0.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2016). Personal Safety Survey, viewed May 20, <https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4906.0.

Barnes, M., Szilassy, E., Herbert, A., Heron, J., Feder, G., Fraser, A., & Barter, C. (2022). Being silenced, loneliness and being heard: Understanding pathways to intimate partner violence & abuse in young adults. A mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13990-4.

Bell, K., & Flood, M. (2020). Change among the Change Agents? Men’s experiences of engaging in Anti-Violence Advocacy as White Ribbon Australia Ambassadors. Masculine power and gender Equality: Masculinities as Change Agents (pp. 55–80). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35162-5.

Beyond DV https://www.beyonddv.org.au/

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Austin: Harvard university press.Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bates, R., Jones, L., Ashworth, E., Gowland, S., Jones, M. (2022). The Contributing Role of Family, School, and Peer Supportive Relationships in Protecting the Mental Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents. School Mental Health, 14(3), 776–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09502-9.

Buchanan, F. (2018). Mothering babies in domestic violence: Beyond attachment theory. Routledge.

Campo, M. (2015). Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses. Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia, 22(3), 33.

Clarke, A., & Wydall, S. (2010). An evaluation of multi-agency working with children and young people who are experiencing the effects of domestic abuse in the Communities First area of Penparcau and Aberystwyth West. Welsh Assembly.

Clements, C. M., Oxtoby, C., & Ogle, R. L. (2008). Methodological issues in assessing psychological adjustment in child witnesses of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 9(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008315870.

Cochran, J. K., Maskaly, J., Jones, S., & Sellers, C. S. (2017). Using structural equations to Model Akers’ Social Learning Theory With Data on intimate Partner violence. Crime & Delinquency, 63(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128715597694.

Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Allen and Unwin.

Copp, J. E., Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A., & Manning, W. D. (2019). The development of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: An examination of key correlates among a sample of young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(7), 1357–1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516651311.

Crawford, M. R., Grant, N. S., & Crews, D. A. (2016). Relationships and rap: Using ecomaps to explore the stories of youth who rap. British Journal of Social Work, 46(1), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu096.

Davies, J., Singh, C., Tebboth, M., Spear, D., Mensah, A., & Ansah, P. (2018). Conducting life history interviews: a how-to guide. Adaptation at Scale in Semi-Arid Regions (ASSAR). Accessed: http://www.assar.uct.ac.za/news/conducting-life-historyinterviews-how-guide.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6.

Fellin, L. C., Callaghan, J. E., Alexander, J. H., Harrison-Breed, C., Mavrou, S., & Papathanasiou, M. (2019). Empowering young people who experienced domestic violence and abuse: The development of a group therapy intervention. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(1), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518794783.

Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2015). A revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011.

Forke, C. M., Catallozzi, M., Localio, A. R., Grisso, J. A., Wiebe, D. J., & Fein, J. A. (2019). Intergenerational effects of witnessing domestic violence: Health of the witnesses and their children. Preventive Medicine Reports, 15, 100942–100942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100942.

Fuller-Thomson, E., Ryan-Morissette, D., Attar-Schwartz, S., et al. (2023). Achieving Optimal Mental Health despite exposure to chronic parental DV: What pathways are Associated with Resilience in Adulthood? J Fam Viol, 38, 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00390-w.

Goodyear, V. A., Armour, K. M., & Wood, H. (2019). Young people learning about health: The role of apps and wearable devices. Learning Media and Technology, 44(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1539011.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Gruber, G., Howell, K. H., & Girz, L. (2009). Factors discriminating among profiles of resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(9), 648–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.01.002.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., & Durlak, J. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. The Future of Children, 27(1), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2017.0001.

Haselschwerdt, M. L., Savasuk-Luxton, R., & Hlavaty, K. (2019). A methodological review and critique of the intergenerational transmission of violence literature. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 20(2), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692385.

Higgins, D. J. (2014). A public health approach to enhancing safe and supportive family environments for children. Family Matters, 96, 39–52.

Hou, J., Yu, L., Fang, X., & Epstein, N. B. (2016). The intergenerational transmission of domestic violence: The role that gender plays in attribution and consequent intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Studies, 22(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1045923.

Humphreys, C. (2007). Domestic violence and child protection: Challenging directions for practice. Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse, UNSW.

Katz, E. (2016). Beyond the physical incident model: How children living with domestic violence are harmed by and resist regimes of coercive control. Child Abuse Review, 25(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2422.

Kindig, D. A. (2007). Understanding population health terminology. The Milbank Quarterly, 85(1), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00479.x.

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339.

Law, C. (2019). Men on the margins? Reflections on recruiting and engaging men in reproduction research. Methodological Innovations, 12(1), 2059799119829425. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799119829425.

Lawson, J. (2012). Sociological theories of intimate partner violence. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(5), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2011.598748.

Manja, V., Nrusimha, A., MacMillan, H. L., Schwartz, L., & Jack, S. M. (2021). Use of ecomaps in qualitative health research. The Qualitative Report, 26(2), 412–442. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4565.

Morris, A., Humphreys, C., & Hegarty, K. (2020). Beyond voice: Conceptualizing children’s agency in domestic violence research through a dialogical lens. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920958909. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920958909.

O’Brien, K. L., Cohen, L., Pooley, J. A., & Taylor, M. F. (2013). Lifting the domestic violence cloak of silence: Resilient australian women’s reflected memories of their childhood experiences of witnessing domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 28(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-012-9484-7.

Olive, J. L. (2014). Reflecting on the tensions between emic and etic perspectives in Life History Research: Lessons learned. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), 1438–5627.

Overlien, C. (2017). Do you want to do some arm wrestling?’: Children’s strategies when experiencing domestic violence and the meaning of age. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12283.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

Sexton-Dhamu, M. J., Livingstone, K. M., Pendergast, F. J., Worsley, A., & McNaughton, S. A. (2021). Individual, socio-environmental and physical-environmental correlates of diet quality in young adults aged 18–30 years. Appetite, 162, 105175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105175.

Smith-Marek, E. N., Cafferky, B., Dharnidharka, P., Mallory, A. B., Dominguez, M., High, J., & Mendez, M. (2015). Effects of Childhood Experiences of Family Violence on Adult Partner Violence: A Meta‐Analytic Review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(4), 498–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12113.

Stanley, N., Ellis, J., Farrelly, N., Hollinghurst, S., Bailey, S., & Downe, S. (2017). What matters to someone who matters to me: Using media campaigns with young people to prevent interpersonal violence and abuse. Health Expectations, 20(4), 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12495.

Stark, E., & Hester, M. (2019). Coercive control: Update and review. Violence Against Women, 25(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218816191.

Stith, S., Rosen, K., Middleton, K., Busch, A., Lundeberg, K., & Carlton, R. (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(3), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x.

Vu, N. L., Jouriles, E. N., McDonald, R., & Rosenfield, D. (2016). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal associations with child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.003.

Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., Vanderhoven, E., Haers, J., & Segaert, B. (Eds.). (2016). Youth 2.0: Social media and adolescence: Connecting, sharing and empowering. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27893-3.

Wilkins, R., Vera-Toscano, E., Botha, F., & Dahmann, S. C. (2021). The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 19. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, the University of Melbourne. Available: https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/3963249/HILDA-Statistical-Report-2021.pdf.

Winfield, A., Hilton, N. Z., Poon, J., Straatman, A. L., & Jaffe, P. G. (2023). Coping strategies in women and children living with domestic violence: Staying Alive. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00488-1.

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341337.

Yule, K., Houston, J., & Grych, J. (2019). Resilience in children exposed to violence: A meta-analysis of protective factors across ecological contexts. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(3), 406–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00293-1.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research study was funded by the Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchanan, F., Borgkvist, A. & Moulding, N. What Helps Young People in Australia Create Healthy Relationships After Growing up in Domestic Violence?. J Fam Viol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00647-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00647-y