Abstract

Purpose

Physically harsh discipline is associated with poor developmental outcomes among children. These practices are more prevalent in areas experiencing poverty and resource scarcity, including in low- and middle-income countries. Designed to limit social desirability bias, this cross-sectional study in rural Uganda estimated caregiver preferences for physically harsh discipline; differences by caregiver sex, child sex, and setting; and associations with indicators of household economic stress and insecurity.

Method

Three-hundred-fifty adult caregivers were shown six hypothetical pictographic scenarios depicting children whining, spilling a drink, and kicking a caregiver. Girls and boys were depicted engaging in each of the three behaviors. Approximately half of the participants were shown scenes from a market setting and half were shown scenes from a household setting. For each scenario, caregivers reported the discipline strategy they would use (time out, beating, discussing, yelling, ignoring, slapping).

Results

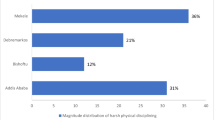

Two thirds of the participants selected a physically harsh discipline strategy (beating, slapping) at least once. Women selected more physically harsh discipline strategies than men (b = 0.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26 to 0.54). Participants shown scenes from the market selected fewer physically harsh discipline strategies than participants shown scenes from the household (b = -0.51; 95% CI, -0.69 to -0.33). Finally, caregivers selected more physically harsh discipline strategies in response to boys than girls. Indicators of economic insecurity were inconsistently associated with preferences for physically harsh discipline.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of physically harsh discipline preferences warrant interventions aimed at reframing caregivers’ approaches to discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Violence against children is prevalent globally, with over half of all children between the ages of 2 and 17 experiencing violence in the past year (Hillis et al. 2016). Comprised of six main types of experiences, violence against children may include sexual violence (e.g., rape, sexual trafficking, sexual harassment, online exploitation); intimate partner violence (including among girls in child and early/forced marriages); youth violence (i.e., that which occurs between children and young adults, with or without weapons); bullying involving repeated harm; emotional or psychological violence (i.e., that which ridicules, intimidates, and rejects children through non-physical hostility); and child maltreatment (i.e., that which involves any type of neglect, abuse, or violent punishment, usually within schools or the household) (World Health Organization, 2020). Across the range of experiences, violence against children is associated with detrimental outcomes. An extensive literature describes pathways from childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, and other forms of maltreatment to severe psychopathology during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Albott et al. 2018; Ashaba et al. 2021, 2022; Cluver et al. 2015; Dube et al. 2001; Hailes et al. 2019; Meinck et al. 2015; Negriff 2020; Satinsky et al. 2021).

Under the umbrella of child maltreatment, physical punishment comprises disciplinary practices that inflict any degree of physical pain or discomfort on the child. It has been described as a form of violence that degrades children and compromises their right to protection (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child 2006). Even if it does not rise to the level of malevolent physical abuse, physically harsh discipline is associated with negative developmental, social, and psychological outcomes (Bender et al. 2007; Cuartas 2021; Durrant and Ensom 2012; Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor 2016; Heilmann et al. 2021). Children exposed to physically harsh discipline practices exhibit lower educational outcomes (Smith and Brooks-Gunn 1997) and greater peer victimization (Ssenyonga et al. 2019), physical aggression (Kingsbury et al. 2020), behavioral problems (Mackenbach et al. 2014; Mulvaney and Mebert 2007; Parent et al. 2011), and depression (Hecker et al. 2016). In response to physical punishment, children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors worsen over time (Heilmann et al. 2021). Functioning in a cyclical nature, these child behaviors may thereby increase caregivers’ use of physically harsh discipline. Furthermore, individuals who are exposed to physical punishment during childhood are more likely to perpetrate similar practices toward their own children (Fulu et al. 2017; Milner et al. 1990; Simons et al. 1991). The consequences of physical punishment are not confined to childhood. Prior studies have found associations between physical punishment during childhood and poor economic (Henry et al. 2018), behavioral (Afifi et al. 2019), and health outcomes (Felitti et al. 1998; Hughes et al. 2017; Jewkes et al. 2010; Kessler et al. 2010) during adulthood.

Some research shows a higher prevalence of physically harsh discipline in rural settings (Alyahri and Goodman 2008), and evidence from diverse contexts has indicated robust associations between poverty and exposure to physically harsh discipline in childhood (Dietz 2000; Drake and Pandey 1996; Ricketts and Anderson 2009). Moreover, the prevalence of physical punishment among children is greater in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries (Hillis et al. 2016). Research suggests that other measures of household insecurity, including food and water insecurity, are associated with both caregiver stress and physically harsh discipline (Helton et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2016).

People living in rural areas of Uganda face pervasive poverty and resource insecurity (Mushavi et al. 2020; Perkins et al. 2018; Tsai et al. 2011; World Bank 2016). Child poverty is particularly prevalent in these areas, with slower progress in household and child-specific indicators when compared to progress in more urban areas (Wasswa 2015). In 1997, Uganda banned corporal punishment in schools (End Violence Against Children, 2022); in 2016, Sect. 106A of The Children (Amendment) Act further prohibited corporal punishment in any institution of learning, with offenders liable to imprisonment (Republic of Uganda, 2016). Physical punishment, however, remains normative in both schools and households (UNICEF 2018). In a national survey from Uganda conducted in 2015, nearly half of children reported experiencing physically harsh discipline at the hand of a parent, caregiver, or other adult relative (UNICEF 2018).

Despite evidence indicating a high prevalence of physical punishment in Uganda, little is known about the extent to which physically harsh discipline practices vary by contexts outside of school settings and how much household economic stress and insecurity drive preferences for these practices. Thus, we conducted a cross-sectional survey to better understand patterns of preferences for physically harsh discipline of young children in rural Uganda, as well as preferences by caregiver sex, child sex, and setting. We also aimed to estimate the associations between indicators of economic security and physically harsh discipline preferences.

Methods

Study setting, population, and procedure

This study took place in Nyakabare Parish, Rwampara District, a rural region in southwestern Uganda. This region was selected through an iterative process. Field site visits to parishes within Mbarara District and informal conversations with local leaders and prominent village residents guided our team’s selection. Nyakabare Parish was favored over other regions due to the limited presence of nongovernmental organizations in the area, the general similarity of the parish compared with other rural parishes in the region, and local leaders’ support for engaging residents in a household survey. The parish is comprised of 8 villages and is located about a five-hour drive from the capital, Kampala. Most parish residents work in subsistence farming, animal husbandry, and/or small-scale enterprise, and many report insecure access to food and water (Mushavi et al. 2020; Perkins et al. 2018; Tsai et al. 2011).

The present study took place within the context of an ongoing population cohort (Takada et al. 2019). Rather than interviewing all caregivers in the parish, and to minimize participant burden, we targeted a convenience sample of 350 study participants of both sexes. Given the study’s focus on understanding the hypothetical circumstances under which a caregiver would express a preference for harsh disciplinary strategies, the subsample of study participants was not randomly selected from the population. In this sub-study, adults 18 years or older were eligible for participation if they or their partner had a biological child 4–12 years of age who primarily stayed in their household. We were interested in this sub-population specifically, rather than adults in general, because of our specific interest in caregivers’ preferences for physically harsh discipline of young children. Individuals unable to adequately communicate with the research team due to cognitive impairment, behavioral problems, deafness, or mutism were excluded.

The study was conducted in 2019–2020. Prior to undertaking study procedures, we held a number of community engagement meetings to introduce the study to parish residents and solicit feedback (Kakuhikire et al. 2021). For this study, a team of research assistants visited the homes of all eligible adults. Research assistants requested study participation and participants provided written informed consent prior to beginning the interview. Those who were unable to read or write were permitted to indicate consent with a thumbprint mark. To administer the survey, the research assistant and participant moved to a private area in or near the participant’s home. Interviews were conducted in Runyankore, the local language, and data were collected with a survey collection software program that could be used remotely with limited access to the internet. Following initial development in English, research assistants translated the measures into Runyankore. Subsequently, other research assistants on the team back-translated the measures into English to confirm fidelity of the translations. This process proceeded iteratively and involved consultation with key informants and pilot testing.

Measures

A survey instrument was adapted from Green et al. (2017) to measure participants’ caregiving discipline preferences. The original instrument was developed for use in a discrete choice experiment conducted in Liberia (Green et al. 2018), with the aim of limiting social desirability bias in participant responses and minimizing potential underestimates of prevalence. Some images from the original instrument were redrawn in accordance with research assistant feedback to improve interpretability. Participants were first presented with pictographic images of different scenarios to confirm understanding of key concepts. The first set of three images depicted child behaviors: 1) whining, 2) spilling a drink, and 3) kicking a caregiver. The second set of images depicted six possible disciplinary actions taken in response to these behaviors: 1) putting the child in “time out”, 2) beating the child, 3) discussing the behavior with the child, 4) yelling at the child, 5) ignoring the child, and 6) slapping the child. After viewing each of the nine images (3 child behaviors, 6 discipline strategies), the participant was asked to describe what was happening in the image. If the participant expressed uncertainty about what was happening, the research assistant explained the image until the participant confirmed understanding. If the research assistant was unable to confirm the participant’s understanding of any of the nine images, that participant was excluded from the remainder of the study procedures described below.

The research assistant presented each participant with six pictographic comic strips, each with an image of a child engaging in a particular behavior (Fig. 1). Three of the six comic strips depicted a girl engaging in one of the prespecified behaviors (whining, spilling a drink, kicking a caregiver), and the other three depicted a boy engaging in the same behaviors. Although the age of the children in the comic strips was unspecified, the images were intended to represent children between the ages of 4 and 12. The order of the scenarios was mixed (but not randomly assigned) such that some participants were shown a girl engaging in the behavior first, while other participants were shown a boy first.

The research assistant then showed the participant images of a caregiver responding to the child using one of the six discipline strategies (time out, beating, discussing, yelling, ignoring, slapping; Fig. 2). The sex of the caregiver depicted in the comic strip was concordant with the study participant’s sex, i.e., women were shown a comic strip depicting a woman caregiver, while men were shown a comic strip depicting a man caregiver. The research assistant asked the participant to select the image that most closely resembled how they would respond in the depicted scenario (i.e., to the child’s behavior; Fig. 2).

To ensure that study participants’ choices of discipline strategies were not driven by a single setting, we presented participants with comic strips depicting scenes from either a household or an open-air, local public market. Allocation to the vignettes was not randomly assigned. Instead, we administered the version of the vignettes set in the household setting until approximately half of the targeted sample size had been interviewed, and we then administered the version of the vignettes set in the market setting to the remainder of the sample. While the household is a private setting where families spend substantial time, the market represents a common public space. Ugandan families in both rural and urban regions visit markets to trade, buy, and sell goods and interact with other village members.

For each scenario, participants were categorized as endorsing physically harsh discipline if they selected ‘beating’ or ‘slapping.’ The primary outcome of interest (i.e., preferences for physically harsh discipline practices) was based on summing responses across the six scenarios to create a variable indicating the total number of scenarios (out of 6) in which the participant selected a physically harsh discipline strategy. Two additional variables were calculated, representing the total number of scenarios in which the participant selected a physically harsh discipline strategy in response to a boy (out of 3) and in response to a girl (out of 3).

The primary explanatory variables of interest were four measures of economic security. Food insecurity was assessed with the 9-item Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (Perkins et al. 2018; Swindale and Bilinsky 2006). Water insecurity was assessed using the 8-item Household Water Insecurity Access Scale (Mushavi et al. 2020; Tsai et al. 2016). Participants were also asked to report whether or not they owned different assets in their household (e.g., goats, chickens, radio, bike, car, flush toilet or ventilated improved pit latrine, etc.). Principal component analysis was applied to categorize participants into household asset wealth quintiles (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Smith et al. 2020). Finally, participants reported their self-perceived relative wealth, i.e., how wealthy they perceived themselves to be in relation to other members of the parish (least poor, better off, average, worse off, or poorest) (Smith et al. 2019).

Ethical approval

All research assistants received multi-day trainings on how to administer surveys for gathering sensitive information, including explicit instructions on how to temporarily halt the survey without arousing suspicion if another person came within earshot. The research assistants also received two additional training courses, one from The AIDS Support Organization on how to handle study participant reports of interpersonal violence (namely, how to receive the information in a sensitive manner and how to provide appropriate referrals to domestic protection resources) and one from a Ugandan counseling psychologist about how to manage sensitive disclosures by study participants. Feedback on the study design was solicited from a community advisory board comprised of eight community leaders, including four women and the district community development officer. We received ethical approval from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research and Ethics Committee and the Partners Human Research Committee. We also obtained clearance from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Data analysis

We tabulated preferences for physically harsh discipline across all three child behaviors, stratified by caregiver sex, child sex, and setting, separately. We then conducted chi-squared tests to compare discipline preferences (i.e., reported any physically harsh discipline strategies vs. none) by caregiver sex and setting. These analyses were conducted separately for boys and girls. Since the total harsh discipline strategy count variable was non-normally distributed and over-dispersed, we fit negative binomial regression models to estimate the associations between preferences for physically harsh discipline (total count) and caregiver sex and setting.

We also fit a series of negative binomial regression models to estimate associations between indicators of economic security and preferences for physically harsh discipline (total count). We fitted separate models for each of the four economic variables: food insecurity, water insecurity, household asset wealth quintile, and self-perceived relative wealth. All models were fitted with cluster-correlated robust estimates of variance to account for potential within-village clustering of the outcome and adjusted for age, caregiver sex, primary school completion, marital status, and setting (i.e., household vs. market). In sensitivity analyses, we stratified these analyses by the sex of the child depicted in the scenario.

As a robustness check to assess the extent to which the convenience sampling may have yielded biased estimates compared to a whole-population sample or a random sample of the population, we used inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs) to recover estimates that would be representative of all Nyakabare Parish residents with children under the age of 18 living in their household. First we fitted a logistic regression model, where inclusion in the subsample of 350 caregivers was specified as the dependent variable, and we included variables that were potentially correlated with participation: age, sex, education level, village of residence, household asset wealth, self-reported overall health, index of social participation, water insecurity, and food insecurity. We then used this regression model to calculate stabilized IPTWs (Cole and Hernán 2008; Hernán et al. 2000; Robins et al. 2000). We incorporated these IPTWs into the regression models specifying preferences for harsh discipline as the dependent variable. Analyses were conducted in Stata MP (version 16, StataCorp LLC, College Station, Tex.).

Results

Three hundred and fifty-three caregivers were recruited to participate in this study. Two individuals did not understand the ‘time out’ discipline strategy and one did not understand the ‘yelling’ discipline strategy, even after discussing the image with the research assistant. These three participants were therefore excluded from further study procedures and from the analysis. In all, 350 caregivers completed the study (Table 1). Of these, 198 (57%) were men. Most participants had completed primary school (n = 221, 63%) and were married (n = 321, 92%). The caregivers in the sample were distributed among 270 households: 191 households provided 1 participant, 78 households provided 2 participants, and 1 household provided 3 participants. Most participants reported mild to severe food insecurity (n = 212, 61%) and more than a third reported mild to severe water insecurity (n = 126, 36%). While just over half of the sample perceived that they were at least equally as well off as other members of the parish (n = 176, 50%), about a quarter believed that they were worse off (n = 90, 26%).

There were no statistically significant differences between participants shown scenes from the household vs. market setting across the following demographic characteristics: age, education level, marital status, household water insecurity, household asset wealth quintile, and self-perceived relative wealth. However, participants shown scenes from the household setting were more likely to report household food insecurity compared with participants shown scenes from the market setting (69% vs. 53%, χ2 = 18.93, p < 0.001).

Across all six scenarios, 77% of women and 59% of men selected a physically harsh discipline strategy at least once. Participants selected a physically harsh discipline strategy 2.21 times on average (standard deviation [SD] = 2.02, median = 2, interquartile range = 0–4) out of a possible six. Generally, caregivers were more likely to select a physically harsh discipline strategy in the comic strips depicting a boy (Table 2; Supplementary File 1). Additionally, caregivers were least likely to select a physically harsh discipline strategy if the child was depicted whining and more likely to select a physically harsh discipline strategy if the child was depicted kicking the caregiver.

Overall, 179 participants (51%) were presented with scenes from a market setting, and 171 participants (49%) were presented with scenes from a household setting. Women were no more likely than men to select a physically harsh discipline strategy in market settings. However, women were more likely than men to select at least one physically harsh discipline strategy in household settings. Compared to only 59% of men (n = 43), 83% of women (n = 81) selected at least one physically harsh discipline strategy for use with girls in the household (χ2 = 11.8, p = 0.001). Similarly, 84% of women (n = 82) and 66% of men (n = 48) selected at least one physically harsh discipline strategy for use with boys in the household (χ2 = 7.37, p = 0.007).

In negative binomial regression models with indicators for caregiver sex, women were more likely than men to select physically harsh discipline strategies overall (b = 0.40, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26 to 0.54, p < 0.001; with inverse probability [IP] weights: b = 0.42, 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.62, p < 0.001). When compared with the baseline standard deviation, the predicted mean difference between women and men was (2.71–1.82)/2.02 = 0.44 SD units, or 40% relative to the baseline overall mean. Participants who were shown scenes from the market setting selected fewer physically harsh discipline strategies than participants who were shown scenes from the household setting (b = -0.51, 95% CI, -0.69 to -0.33, p < 0.001; with IP weights: b = -0.48, 95% CI, -0.79 to -0.16, p = 0.003). When compared with the baseline standard deviation, the predicted mean difference between household and markets settings was (2.77–1.66)/2.02 = 0.55 SD units, or 50% relative to the baseline overall mean.

In the multivariable negative binomial regression models, none of the indicators of economic security were reliably associated with preferences for physically harsh discipline (Table 3; Supplementary File 2). The signs of the estimated coefficients were not consistent across indicators: food insecurity was positively associated with preferences for physically harsh discipline (p-values ranging from 0.06 to 0.28), while water insecurity had null associations (regression coefficients ranging from -0.07 to 0.02 and p-values ranging from 0.72 to 0.91); and similarly, being in the poorest quintile as measured by asset wealth was positively associated with preferences for physically harsh discipline (p = 0.07) but being in the poorer categories of self-perceived wealth was negatively associated (p-values ranging from 0.03 to 0.44). Similarly, indicators of economic security were inconsistently associated with the cumulative number of physically harsh discipline preferences when the analyses were stratified by child sex (Supplementary File 3).

Discussion

In this study, over two-thirds of caregivers selected a physically harsh discipline strategy at least once when presented with pictographic images of hypothetical child behaviors in a household or market setting. While the prevalence of preferences for physically harsh discipline was high across contexts, these preferences were more common among women caregivers compared to men caregivers and were more common in response to behaviors in the household setting compared to the market setting. These estimates were small to moderate in magnitude. Generally, caregivers selected harsh discipline strategies in scenes depicting boys more frequently than in scenes depicting girls. Finally, within this rural setting with insecure access to food and water (Mushavi et al. 2020; Perkins et al. 2018; Tsai et al. 2011), physically harsh discipline preferences were not reliably associated with indicators of economic security.

These findings reflect research from other settings across eastern and southern Africa that show a high prevalence of physically harsh discipline, both in the school and household (Devries et al. 2014; Lansford et al. 2010; O'Neil et al. 2009). Preferences for physically harsh discipline in the present study were consistent with national survey data from Uganda (Uganda Burea of Statistics 2018; UNICEF 2018). For example, in the Uganda 2016 Demographic and Health Survey, 68.8% of respondents from the southwestern region, which includes Mbarara District, endorsed the belief that physical punishment is needed to raise a child properly (Uganda Burea of Statistics 2018). As the present study was designed specifically to limit response bias (Green et al. 2017, 2018), our data confirm a high prevalence of preferences for physical punishment in this setting. The use of hypothetical, pictographic scenarios allowed caregivers to describe their preferences while not having to report actual practices. Although physically harsh discipline remains normative in this setting (Lokot et al. 2020; Ssenyonga et al. 2019), caregivers may still be reluctant to report their true discipline practices. To the extent that social desirability bias remains an important predictor of reporting, other methods (e.g., list experiments; Lépine et al. 2020; Moseson et al. 2015) may elicit even more accurate estimates of such preferences.

Our findings build on prior research by demonstrating differences in preferences for physically harsh discipline by caregiver sex, setting, and child sex. A global study across nine countries found that mothers were more likely than fathers to use corporal punishment. Similarly, boys were more likely than girls to be disciplined through physical means (Lansford et al. 2010). In Uganda, women are more likely to assume responsibility for caregiving and domestic work, while men are more likely to work outside of the home (Gabola et al. 2018). As such, women caregivers spend more time with the children and take on the role of disciplinarian. During the limited time they spend with their children, and to compensate for their long absences, men might be less likely to use physically harsh discipline. Gendered norms and idealized masculinity in this setting may further decrease the likelihood that men engage in caregiving activities, including setting boundaries and disciplining children.

The more limited prevalence of physically harsh discipline preferences in the market setting versus the household setting may reflect a preference for delaying physically harsh discipline until the caregiver and child are in a secluded location. Caregivers may be less likely to subject their child to physically harsh discipline in public settings due to stigma associated with such behavior, particularly in light of the ban on corporal punishment in schools (Republic of Uganda 2016). Even though the use of physically harsh discipline is widely practiced and culturally accepted in Uganda (Lokot et al. 2020; Ssenyonga et al. 2019), caregivers may not want others to witness them using these practices. Descriptive norms (i.e., what most people think, feel, or do) might not reflect injunctive norms (i.e., what most people approve of) in this context. Nonetheless, prior studies have shown a strong association between stated preferences for harsh discipline and engagement in harsh disciplinary behaviors (Johnson et al. 2022).

Unlike past research, we did not find that men or women living in conditions of economic insecurity (i.e., potentially fostering more parenting stress) were more likely to report preferences for physically harsh discipline (Johnson et al. 2022). This finding may reflect cultural norms around the use of physically harsh discipline that hold across socioeconomic strata. Additionally, since this study was conducted in a rural setting characterized by considerable food and water insecurity (Mushavi et al. 2020; Perkins et al. 2018; Tsai et al. 2011), associations between economic insecurity and harsh discipline may extend throughout the entire study setting. In a qualitative study of 12 mothers living in poverty in Kampala, Uganda, for example, women described using corporal punishment with their children to ensure good behavior, manage scarce resources, and protect their children from health risks (Boydell et al. 2017). Future research may consider sampling caregivers from multiple regions of the country to assess relationships between wealth and discipline in settings with greater economic variability.

The high prevalence of preferences for physical punishment in this setting is cause for concern. Although there is a spectrum of physically harsh discipline strategies, ranging from malevolent behavior intentionally used to cause physical harm to the occasional spanking (World Health Organization, 2020), the use of strategies at all points along this continuum are associated with poor developmental outcomes (Cuartas 2021; Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor 2016; Hecker et al. 2016; Kingsbury et al. 2020; Mackenbach et al. 2014). While some research indicates that normative perceptions of physically harsh discipline partially moderate the relationship between physical punishment and detrimental outcomes (Gershoff et al. 2010; Lansford et al. 2005), other research finds that physically harsh discipline negatively affects development, even in cultures where these practices are perceived as normative (Pace et al. 2019; Yildrim et al. 2020). Thus, our findings support the need for intervention strategies that encourage alternative, non-physically harsh discipline (Giusto et al. 2020; Puffer et al. 2020).

Parenting resources available to caregivers in Uganda are extremely scarce, particularly among those living in rural settings. Developmentally appropriate interventions that emphasize nurturing care are needed (Black et al. 2017, 2021). These types of interventions have the potential to change norms and attitudes around discipline (Ashburn et al. 2017; Kyegombe et al. 2017; Lokot et al. 2020), reduce the use of physically harsh discipline, and minimize negative developmental outcomes among children. Parenting interventions, potentially led by peers (Giusto et al. 2021a), that promote non-physical discipline strategies and encourage caregivers to discuss boundaries and consequences may help parents better support and empower their children. Although physically harsh discipline preferences were more prevalent among women, interventions should include fathers or other male caregivers (Ashburn et al. 2017; Giusto et al. 2021b; Giusto and Puffer 2018; Lundahl et al. 2007). Several such interventions have been implemented in eastern, western, and southern Africa and have led to reductions in physically harsh discipline practices, improvements in positive parenting, and improvements in child, adolescent, and caregiver outcomes (Ashburn et al. 2017; Betancourt et al. 2014; Cluver et al. 2016, 2018; Lachman et al. 2017; Puffer et al. 2015; Siu et al. 2017; Ward et al. 2019).

Limitations

First, our findings may not generalize outside of this study setting. However, as our estimates of the overall prevalence of physically harsh discipline preferences mirror the findings on the prevalence of physical abuse and corporal punishment across eastern Africa, it is likely that our findings are reflective of prevalence rates in other rural settings in the region. Second, the limited sample size prevented us from disaggregating analyses by type or severity of discipline strategy (i.e., beating vs. slapping), or considering associations with harsh, yet non-physical punishment (i.e., yelling). Further, the sample size prevented us from estimating potentially meaningful effect sizes. For example, in the analysis of preferences for harsh discipline by household asset wealth quintile, at the means of the covariates the predicted number of scenarios in which a study participant selected a harsh discipline strategy was 2.45 among study participants in the poorest wealth quintile and 2.0 among study participants in the least poor wealth quintile. This represents a 0.45/2.02 = 0.22 SD units difference, or a “small” effect size. While this analysis, for example, could rule out statistically significant larger effect sizes, we could not exclude the possibility of smaller effect sizes. Third, although we estimated associations between discipline preferences and economic security, we did not collect data on child outcomes, including development, school performance, mental health, or physical health. Future research from this setting may include child measures to link with data on caregiver discipline. Fourth, exposure to the vignettes in the household setting vs. vignettes in the market setting was not randomly assigned. Study participants in the two groups were largely similar but did differ in the proportions reporting food insecurity. In the multivariable regression models, which adjusted for household vs. market setting, food insecurity did not have a statistically significant association with preferences for physically harsh discipline, but the p-values for the food insecurity categories were closer to the alpha 0.05 threshold (ranging from 0.06 to 0.28). It is possible that there were unobserved differences in socioeconomic status (not captured by differences in food insecurity, water insecurity, household asset wealth, and self-perceived relative wealth) differential by setting that could have contributed to the observed differences in preferences for physically harsh discipline. Fifth, our use of a convenience sampling strategy to identify participants for this sub-study may have introduced bias. For example, it is possible that unobserved characteristics associated with the propensity to participate in the sub-study may have been correlated with both economic insecurity and with preferences for physically harsh discipline in such a way as to bias the estimated associations either toward or away from the null. However, it is reassuring that IP weighted estimates – representative of all parish residents with a child under the age of 18 living in the household – did not yield substantive differences.

Finally, the pictographic scenarios contained limited explicit information, and study participants’ responses likely would have been conditioned on their interpretation of the pictographs. For example, images did not contain detail on child age. It is possible that caregivers may have selected different discipline strategies if they perceived the age of the depicted child to be younger vs. older. It is also possible that some study participants could have made assumptions about the age of the child depicted, and this could have informed their responses differentially compared with other study participants. Consistent with this possibility, research assistants did report that some participants tried to ask about the age of the children in the images before providing their response, and that other study participants provided long justifications (verbally) for their selections prior to making a final answer. However, we note that, in order for any putative perceptual differences to bias our estimates toward or away from the null, study participants’ perceptions of the depicted children’s ages would need to be systematically different, on average, according to the variables of interest. For example, study participants shown the scenes from the home setting would need to systematically perceive the depicted children’s ages to be older or younger compared with study participants shown the scenes from the market setting. Alternatively, women participants would need to systematically perceive the depicted children’s ages to be older or younger compared with men participants. Based on our knowledge of the participants and the study setting, we can think of no factors that can provide a reasonable explanation for why this might be the case.

Conclusions

In this study, we found a high prevalence of physically harsh discipline preferences among caregivers in rural Uganda, with a higher prevalence seen among women and in household settings. While we did not find associations between measures of economic security and physically harsh discipline preferences, the high prevalence may broadly reflect poverty in this setting, as well as pervasive social norms and attitudes around child discipline. Given links between physically harsh discipline and poor developmental outcomes, family interventions that provide education and alternative discipline strategies are warranted.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author ENS upon request.

References

Afifi, T. O., Fortier, J., Sareen, J., & Taillieu, T. (2019). Associations of harsh physical punishment and child maltreatment in childhood with antisocial behaviors in adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 2(1), e187374. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7374

Albott, C. S., Forbes, M. K., & Anker, J. J. (2018). Association of childhood adversity with differential susceptibility of transdiagnostic psychopathology to environmental stress in adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e185354. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5354

Alyahri, A., & Goodman, R. (2008). Harsh corporal punishment of Yemeni children: Occurrence, type and associations. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32(8), 766–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.01.001

Ashaba, S., Cooper-Vince, C. E., Maling, S., Satinsky, E. N., Baguma, C., Akena, D., ... Tsai, A. C. (2021). Childhood trauma, major depressive disorder, suicidality, and the modifying role of social support among adolescents living with HIV in rural Uganda. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, 100094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100094

Ashaba, S., Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C., Satinsky, E. N., Perkins, J. M., Rasmussen, J. D., ... Tsai, A. C. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences, alcohol consumption, and the modifying role of social participation: Population-based study of adults in southwestern Uganda. SSM - Mental Health, 2, 100062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2022.100062

Ashburn, K., Kerner, B., Ojamuge, D., & Lundgren, R. (2017). Evaluation of the Responsible, Engaged, and Loving (REAL) Fathers Initiative on physical child punishment and intimate partner violence in northern Uganda. Prevention Science, 18(7), 854–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0713-9

Bender, H. L., Allen, J. P., Boykin McElhaney, K., Antonishak, J., Moore, C. M., O’Beirne Kelly, H., & Davis, S. M. (2007). Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Developmental Psychopathology, 19(1), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070125

Betancourt TS, Ng LC, Kirk CM, Munyanah M, Mushashi C, Ingabire C, ... Sezibera V (2014) Family-based prevention of mental health problems in children affected by HIV and AIDS: an open trial. AIDS, 28(Suppl 3), S359-S368. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000336

Black, M. M., Behrman, J. R., Daelmans, B., Prado, E. L., Richter, L., Tomlinson, M., ... Yoshikawa, H. (2021). The principles of Nurturing Care promote human capital and mitigate adversities from preconception through adolescence. BMJ Global Health, 6(4), e004436

Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., ... Grantham-McGregor, S. (2017). Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. The Lancet, 389(10064), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

Boydell, N., Nalukenge, W., Siu, G., Seeley, J., & Wight, D. (2017). How mothers in poverty explain their use of corporal punishment: A qualitative study in Kampala Uganda. European Journal of Development Research, 29(5), 999–1016. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0104-5

Cluver, L., Meinck, F., Yakubovich, A., Doubt, J., Redfern, A., Ward, C., ... Gardner, F. (2016). Reducing child abuse amongst adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A pre-post trial in South Africa. BMC Public Health, 16(567). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3262-z

Cluver, L., Orkin, M., Boyes, M. E., & Sherr, L. (2015). Child and adolescent suicide attempts, suicidal behavior, and adverse childhood experiences in South Africa: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.001

Cluver, L. D., Meinck, F., Steinert, J. I., Shenderovich, Y., Doubt, J., Herrero Romero, R., ... Gardner, F. (2018). Parenting for Lifelong Health: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000539

Cole, S. R., & Hernán, M. A. (2008). Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168(6), 656–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn164

Cuartas, J. (2021). Corporal punishment and early childhood development in 49 low- and middle-income countries. Child Abuse and Neglect, 120, 105205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105205

Devries, K. M., Child, J. C., Allen, E., Walakira, E., Parkes, J., & Naker, D. (2014). School violence, mental health, and educational performance in Uganda. Pediatrics, 133(1), e129–e137. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2007

Dietz, T. L. (2000). Disciplining children: Characteristics associated with the use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24(12), 1529–1542. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00213-1

Drake, B., & Pandey, S. (1996). Understanding the relationship between neighborhood poverty and specific types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20(11), 1003–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(96)00091-9

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D. P., Williamson, D. F., & Giles, W. H. (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the lifespan. JAMA, 286(24), 3089–3096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.24.3089

Durrant, J., & Ensom, R. (2012). Physical punishment of children: Lessons from 20 years of research. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(12), 1373–1377. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101314

End Violence Against Children. (2022). Corporal punishment of children in Uganda.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., ... Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography, 38(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0003

Fulu, E., Miedema, S., Roselli, T., McCook, S., Chan, K. L., Haardorfer, R., & Jewkes, R. (2017). Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: Findings from the UN Multi-country study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health, 5(5), e512–e522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30103-1

Gabola, M., Katunze, M., Ssewanyana, M., Ahikire, J., Musiimenta, P., Boonabaana, B., & Ssennono, V. (2018). Gender Roles and The Care Economy in Ugandan Households: The Case of Kaabong, Kabale and Kampala Districts.

Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

Gershoff, E. T., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Zelli, A., Deater-Deckard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2010). Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development, 81(2), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01409.x

Giusto, A., Green, E. P., Simmons, R. A., Ayuku, D., Patel, P., & Puffer, E. S. (2020). A multiple baseline study of a brief alcohol reduction and family engagement intervention for fathers in Kenya. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(8), 708–725. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000559

Giusto, A., Johnson, S. L., Lovero, K. L., Wainberg, M. L., Rono, W., Ayuku, D., & Puffer, E. S. (2021a). Building community-based helping practices by training peer-father counselors: A novel intervention to reduce drinking and depressive symptoms among fathers through an expanded masculinity lens. International Journal of Drug Policy, 95(103291). https://doi.org/10.1017/j.drugpo.2021.103291

Giusto, A., Mootz, J. J., Korir, M., Jaguga, F., Mellins, C. A., Wainberg, M. L., & Puffer, E. S. (2021b). When my children see their father is sober, they are happy: A qualitative exploration of family system impacts following men's engagement in an alcohol misuse intervention in peri-urban Kenya. SSM-Mental Health, 1(100019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100019

Giusto, A., & Puffer, E. (2018). A systematic review of interventions targeting men's alcohol use and family relationships in low- and middle-income countries. Global Mental Health, 5, e10. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.32

Green, E., Chase, R. M., Zayzay, J., Finnegan, A., & Puffer, E. S. (2018). The impact of the 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Liberia on parent preferences for harsh discipline practices: A quasi-experimental, pre-post design. Global Mental Health, 5(e1). https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.24

Green, E. P., Chase, R. M., Zayzay, J., Finnegan, A., & Puffer, E. S. (2017). A discrete choice task to measure preferences for harsh discipline among parents of young children. PsyArXiv.

Hailes, H. P., Yu, R., Danese, A., & Fazel, S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: An umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30286-X

Hecker, T., Hermenau, K., Salmen, C., Teicher, M., & Elbert, T. (2016). Harsh discipline relates to internalizing problems and cognitive functioning: Findings from a cross-sectional study with school children in Tanzania. BMC Psychiatry, 16(118). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0828-3

Heilmann, A., Mehay, A., Watt, R. G., Kelly, Y., Durrant, J. E., van Turnhout, J., & Gershoff, E. T. (2021). Physical punishment and child outcomes: A narrative review of prospective studies. The Lancet, 398(10297), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00582-1

Helton, J. J., Jackson, J. B., Boutwell, B. B., & Vaughn, M. G. (2018). Household food insecurity and parent-to-child aggression. Child Maltreatment, 24(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559518819141

Henry, K. L., Fuko, C. J., & Merrick, M. T. (2018). The harmful effect of child maltreatment on economic outcomes in adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1134–1141. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304635

Hernán, M. A., Brumback, B., & Robins, J. M. (2000). Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology, 11(5), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

Huang, K. Y., Abura, G., Theise, R., & Nakigudde, J. (2016). Parental depression and associations with parenting and children’s physical and mental health in a sub-Saharan African setting. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(4), 517–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0679-7

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., ... Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356-e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Jewkes, R. K., Dunkle, K., Nduna, M., Jama, P. N., & Puren, A. (2010). Associations between childhood adversity and depression, substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34(11), 833–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.05.002

Johnson, S. L., Rieder, A., Green, E. P., Finnegan, A., Chase, R. M., Zayzay, J., & Puffer, E. S. (2022). Parenting in a conflict-affected setting: Discipline practices, parent-child interactions, and parenting stress in Liberia. Journal of Family Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0001041

Kakuhikire, B., Satinsky, E. N., Baguma, C., Rasmussen, J. D., Perkins, J. M., Gumisiriza, P., ... Tsai, A. C. (2021). Correlates of attendance at community sensitization meetings held in advance of bio-behavioral research studies: A longitudinal, sociocentric social network study in rural Uganda. PLoS Medicine, 18(7), e10037005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003705

Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Greif Green, J., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., ... Williams, D. R. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499

Kingsbury, M., Sucha, E., Manion, I., Gilman, S. E., & Colman, I. (2020). Adolescent mental health following exposure to positive and harsh parenting in childhood. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(6), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719889551

Kyegombe, N., Namakula, S., Mulindwa, J., Lwanyaaga, J., Naker, D., Namy, S., ... Devries, K. M. (2017). How did the Good School Toolkit reduce the risk of past week physical violence from teachers to students? Qualitative findings on pathways of change in schools in Luwero, Uganda. Social Science and Medicine, 180, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.008

Lachman, J. M., Cluver, L., Ward, C. L., Hutchings, J., Mlotshwa, S., Wessels, I., & Gardner, F. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of a parenting program to reduce the risk of child maltreatment in South Africa. Child Abuse and Neglect, 72, 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.08.014

Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Oburu, P., Palmerus, K., & Quinn, N. (2005). Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development, 76(6), 1234–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x

Lansford, J. E., Pe, L., Al-Hassan, S., Bacchini, D., Bombi, A. S., Bornstein, M. H., ... Zelli, A. (2010). Corporal punishment of children in nine countries as a function of child gender and parent gender. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/672780

Lépine, A., Treibich, C., & D'Exelle, B. (2020). Nothing but the truth: Consistency and efficiency of the list experiment method for the measurement of sensitive health behaviours. Social Science and Medicine, 266(113326). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113326

Lokot, M., Bhatia, A., Kenny, L., & Cislaghi, B. (2020). Corporal punishment, discipline and social norms: A systematic review in low- and middle-income countries. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 55, 101507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101507

Lundahl, B. W., Tollefson, D., Risser, H., & Lovejoy, C. (2007). A meta-analysis of father involvement in parent training. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507309828

Mackenbach, J. D., Ringoott, A. P., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Hofman, A., ... Tiemeier, H. W. (2014). Exploring the relation of harsh parental discipline with child emotional and behavioral problems by using multiple informants. The Generation R study. PloS One, 9(8), e104793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104793

Meinck, F., Cluver, L. D., Boyes, M. E., & Mhlongo, E. L. (2015). Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(1), 81–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014523336

Milner, J. S., Robertson, K. R., & Rogers, D. L. (1990). Childhood history of abuse and adult child abuse potential. Journal of Family Violence, 5, 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00979136

Moseson, H., Massaquoi, M., Dehlendorf, C., Bawo, L., Dahn, B., Zolia, Y., ... Gerdts, C. (2015). Reducing under-reporting of stigmatized health events using the List Experiment: Results from a randomized, population-based study of abortion in Liberia. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(6), 1951–1958. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv174

Mulvaney, M. K., & Mebert, C. J. (2007). Parental corporal punishment predicts behavior problems in early childhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(3), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.389

Mushavi, R. C., Burns, B. F. O., Kakuhikire, B., Owembabazi, M., Vorechovska, D., McDonough, A. Q., ... Tsai, A. C. (2020). When you have no water, it means you have no peace: A mixed-methods, whole-population study of water insecurity and depression in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine, 245, 112561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112561

Negriff, S. (2020). ACEs are not equal: Examining the relative impact of household dysfunction versus childhood maltreatment on mental health in adolescence. Social Science and Medicine, 245, 112696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112696

O’Neil, V., Killian, B., & Hough, A. (2009). The socio-historical context of in-school corporal punishment in a KwaZulu-Natal setting. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 19(1), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2009.10820269

Pace, G. T., Lee, S. J., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2019). Spanking and young children’s socioemotional development in low- and middle-income countries. Child Abuse and Neglect, 88, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.003

Parent, J., Forehand, R., Merchant, M. J., Edwards, M. C., Conners-Burrow, N. A., Long, N., & Jones, D. J. (2011). The relation of harsh and permissive discipline with child disruptive behaviors: Does child gender make a difference in an at-risk sample? Journal of Family Violence, 26(7), 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9388-y

Perkins, J., Nyakato, V., Kakuhikire, B., Tsai, A., Subramanian, S., Bangsberg, D., & Christakis, N. (2018). Food insecurity, social networks and symptoms of depression among men and women in rural Uganda: A cross-sectional, population-based study. Public Health Nutrition, 21(5), 838–848. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002154

Puffer, E. S., Friis Healy, E., Green, E. P., Giusto, A. M., Kaiser, B. N., Patel, P., & Ayuku, D. (2020). Family functioning and mental health changes following a family therapy intervention in Kenya: A pilot trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(12), 3493–3508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01816-z

Puffer, E. S., Green, E. P., Chase, R. M., Sim, A. L., Zayzay, J., Friis, E., ... Boone, L. (2015). Parents make the difference: A randomized-controlled trial of a parenting intervention in Liberia. Global Mental Health, 2, e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2015.12

Republic of Uganda. (2016). The Children (Amendment) Act. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/104395/127307/F-171961747/UGA104395.pdf

Ricketts, H., & Anderson, P. (2009). The impact of poverty and stress on the interaction of Jamaican caregivers with young children. International Journal of Early Years Education, 16(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760801892276

Robins, J. M., Hernán, M. A., & Brumback, B. (2000). Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology, 11(5), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011

Satinsky, E. N., Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C., Rasmussen, J. D., Ashaba, S., Cooper-Vince, C. E., ... Tsai, A. C. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences, adult depression, and suicidal ideation in rural Uganda: A cross-sectional, population-based study. PLoS Medicine, 18(5), e1003642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003642

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., & Wu, C. (1991). Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.159

Siu, G. E., Wight, D., Seeley, J., Namutebi, C., Sekiwunga, R., Zalwango, F., & Kasule, S. (2017). Men’s involvement in a parenting programme to reduce child maltreatment and gender-based violence: Formative evaluation in Uganda. The European Journal of Development Research, 29, 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0103-6

Smith, J. R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Correlates and consequences of harsh discipline for young children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 151(8), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170450027004

Smith, M. L., Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C., Rasmussen, J. D., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2020). Do household asset wealth measurements depend on who is surveyed? Asset reporting concordance within multi-adult households in rural Uganda. Journal of Global Health, 10(1), 010412. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010412

Smith, M. L., Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C., Rasmussen, J. D., Perkins, J. M., Cooper-Vince, C. E., ... Tsai, A. C. (2019). Relative wealth, subjective social status, and their associations with depression: Cross-sectional, population-based study in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine-Population Health, 8, 100448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100448

Ssenyonga, J., Muwonge, C. M., & Hecker, T. (2019). Prevalence of family violence and mental health and their relation to peer victimization: A representative study of adolescent students in Southwestern Uganda. Child Abuse and Neglect, 98, 104194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104194

Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2006). Development of a universally applicable household food insecurity measurement tool: Process, current status, and outstanding issues. Journal of Nutrition, 136(5), 1449S-1452S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.5.1449S

Takada, S., Nyakato, V., Nishi, A., O'Malley, A. J., Kakuhikire, B., Perkins, J. M., ... Tsai, A. C. (2019). The social network context of HIV stigma: Population-based, sociocentric network study in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine, 233, 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.012

Tsai, A. C., Bangsberg, D. R., Emenyonu, N., Senkungu, J. K., Martin, J. N., & Weiser, S. D. (2011). The social context of food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine, 73(12), 1717–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.026

Tsai, A. C., Kakuhikire, B., Mushavi, R., Vořechovská, D., Perkins, J. M., McDonough, A. Q., & Bangsberg, D. R. (2016). Population-based study of intra-household gender differences in water insecurity: Reliability and validity of a survey instrument for use in rural Uganda. Journal of Water and Health, 14(2), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2015.165

Uganda Burea of Statistics. (2018). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016.

UNICEF. (2018). Uganda Violence Against Children Survey: Findings from a National Survey.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2006). General Comment No. 8. The right of the child to protection from corporal punishment and other cruel or degrading forms of punishment. Geneva.

Ward, C. L., Wessels, I. M., Lachman, J. M., Hutchings, J., Cluver, L. D., Kassanjee, R., ... Gardner, F. (2019). Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children: A randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(4), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13129

Wasswa, F. (2015). Multidimensional child poverty and its determinants: A case of Uganda. University of Canberra.

World Bank.(2016). Poverty headcount ration at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Uganda.

World Health Organization. (2020). Violence against children.

Yildrim, E. D., Roopnarine, J. L., & Abolhassani, A. (2020). Maternal use of physical and non-physical forms of discipline and preschoolers' social and literacy skills in 25 African countries. Child Abuse and Neglect, 106, 104513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104513

Acknowledgements

We thank the HopeNet cohort study participants, without whom this research would not be possible. We also thank members of the HopeNet study team for research assistance; in addition to the named study authors, HopeNet and other collaborative team members who contributed to data collection and/or study administration during all or any part of the study were as follows: Dickson Beinomugisha, Patrick Gumisiriza, Justus Kananura, Allen Kiconco, Viola Kyokunda, Mercy Juliet, Patrick Lukwago Muleke, Elizabeth B. Namara, and Immaculate Ninsiima. We also thank Roger Hofmann of West Portal Software Corporation (San Francisco, Calif.) for developing and customizing the Computer Assisted Survey Information Collection Builder software program used to collect the survey data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium This project was funded by Friends of a Healthy Uganda and U.S. National Institutes of Health R01MH113494-01 awarded to ACT. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee and the Partners Human Research Committee. Study clearance was obtained from the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology.

Conflict of Interest

ACT reports receiving a financial honorarium from Elsevier, Inc. for his work as Co-Editor-in-Chief of the journal SSM-Mental Health.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Satinsky, E.N., Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C. et al. Caregiver preferences for physically harsh discipline of children in rural Uganda. J Fam Viol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00536-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00536-4