Abstract

A range of SiC–B4C composites have been prepared by pressureless sintering, using different proportions of two sizes of B4C; 7 and 70 μm. The interfacial area between the B4C and SiC has been quantified and is shown to have a significant effect on both densification and the resultant microstructure of the composites. SiC/B4C interfaces typically hinder densification. SiC/B4C interfacial area is also shown to be related to grain growth and polytype distribution in the SiC. With more SiC/B4C interfacial area, grain growth in the SiC is restricted and less of the SiC transforms from the starting 6H polytype to the 4H one. It is therefore suggested that it may be possible to use SiC/B4C interfacial area as a means by which to engineering the microstructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SiC and B4C are of interest owing to their combination of high hardness, low density and high thermal tolerance, even when compared with other common engineering ceramics. However, B4C is known to be difficult, and thus costly, to form into a dense body, particularly by pressureless sintering. This is because of its highly covalent structure and corresponding low self-diffusivity [1]. Despite these drawbacks, because it has a lower density than SiC and can display higher hardness, significant interest in its use remains. Given that SiC and B4C have some capacity to act as sintering aids for each other, composite materials have been suggested as a pragmatic approach to producing carbide ceramic materials. Further, in spite of the associated difficulties, pressureless sintering of these materials is preferred to hot pressing techniques, if the resulting composites are to be commercially viable. Reaction bonding has also been used to produce these composites [2], but results in reduced hardness and strength compared with sintered materials [3] and so is of less interest for high performance applications. Use of coarser B4C also has the potential to reduce the cost of the material. However, this may impair the ability of a composite to densify, given the low self-diffusivity of B4C. This is significant since a primary consideration in components where hardness is important, such as those for wear applications, is that materials must reach a high percentage of their theoretical density (%TD). When using fine B4C, composites with compositions ranging from 10 to 90 wt% B4C have been pressureless sintered to 98 %TD, with only C additions [4]; this suggests that almost full densification is possible under the correct conditions. However, it has also been reported that B4C will not demonstrate self-densification with a particle size (as indicated by a median diameter, d 50, value) above ~8 μm [5]. One potential solution to this is to surround a coarse B4C material with a SiC matrix, which can be readily prepared with B and C additives to achieve good densification more readily than B4C.

As well as %TD, the grain structure is important in determining the mechanical performance of the ceramic material. SiC has long been known to display discontinuous grain growth, both under liquid phase sintering (LPS) [6], and also under solid state sintering conditions [7, 8]. Discontinuous grain growth is more common under pressureless sintering conditions than under pressure-assisted densification, since higher temperatures are typically required to produce adequate density in the sintered body. The use of a second inert phase, such as graphite, has been demonstrated to limit this [9]. Similar effects have been achieved in Al2O3, using B4C as an inert phase [10, 11]. However, the degree of control of grain growth that may be achieved using a second phase is not well understood. A distinct trend has been observed for B, (added as B4C) in β-SiC [12]. It was observed that the addition of a small amount of B increased grain growth; this is in agreement with previous work suggesting that B typically increases diffusivity and mass transport in SiC [13]. However, further addition of B4C inhibited grain growth. Since B has a low solid solubility in SiC [14], the remaining B4C was likely to be inert. This suggests that the interfaces present between SiC and B4C were inhibiting grain growth, as was observed with graphite addition [9] and when 5 wt% B4C prevented discontinuous grain growth in a pressureless sintered SiC [15].

Sintering of SiC is also linked to changes in the polytype composition of the material, which may be important since it has been suggested that polytype transformations could act as a micro-plasticity mechanism under certain conditions [16]. Polytype transformation has been observed by Raman spectroscopy in SiC subject to machining [17] but is more commonly associated with certain grain growth mechanisms, including β to α transformation by dissolution-precipitation during LPS [18]. In α-SiC, it has also been observed that LPS 6H SiC tends to transform to 4H when abnormal grain growth occurs when an aluminium–boron–carbon (ABC) phase is used [19–21]. Further, in a related study, increased transformation from 6H to 4H was observed with increased sintering temperature for LPS α-SiC [22]. However, LPS seems to produce a smaller effect on polytype transformation in α-SiC than in β-SiC [23]. This may result from the greater thermal stability of 6H SiC compared with 3C. For both 3C and 6H SiC, however, the transformation to 4H is typically associated with the formation of a liquid phase and also therefore with grain growth.

Given that it appears that a second phase in these materials can influence the microstructural evolution in SiC, it is necessary to consider means of quantifying the degree of interaction between two phases. This can be accomplished using image segmentation methods, such as phase separation [24]. However, in the present work, the total SiC/B4C interfacial area/unit volume in different material has been quantified directly.

In the present work, particulate SiC–B4C composites have been produced by adding two relatively coarse grades of B4C to a SiC matrix. The effects of the SiC/B4C interfacial area in these composites are discussed. It is suggested that the interfacial area affects densification, together with material diffusivity and powder size effects. Further, the amount of SiC/B4C interfacial area has a significant effect on the microstructural evolution, changing the grain size and type within the SiC matrix.

Experimental procedure

All samples were prepared with an α-SiC starting powder, (SIKA Sintex 15 C) with d 50 measured as 0.8 μm on a Malvern Mastersizer 3000, surface area 15 ± 1 m2 g−1 and 0.83 wt% total O. Two sizes of B4C were used with d 50 values of approximately 7- and 70-μm (Sigma Aldrich research purity B4C). According to LECO analysis provided by AMG analytical services, Rotherham, UK, the 7-μm Sigma grade has 0.160 wt% O and 70-μm Sigma grade has 0.041 wt% O.

Powder blends were prepared by dispersion of both SiC and the B4C powders in a slip. To facilitate densification in the SiC, 1 wt% of 1-μm B4C, H. C. Starck HS grade, and an organic C source (yielding approximately 4 wt% C) were added to all powder blends. A fugitive binder system was also added to all blends. Materials with B4C additions of 10, 20 and 30 wt% were prepared with both the 7- and 70-μm grades. All powder blends contained SiC as the remaining wt%, forming the matrix phase. A standard SiC, containing 1 wt% of the 1-μm B4C and the C source, but no coarse B4C was also prepared as a reference material. The resulting slips were freeze dried and sieved through a 355-μm mesh. Discs of 20 mm diameter, approximately 5 mm thick were prepared, by uniaxial pressing at 345 ± 2 MPa. Sintering of all parts was carried out in graphite trays in a graphite resistance furnace under Ar. A top temperature of 2125 °C with a hold of 1 h was used for all samples.

Sample mass was measured using a Mettler-Toledo balance to ±0.001 g and density was calculated using the Archimedes method in reverse osmosis (RO) water. The %TD was calculated from the density using the rule of mixtures and assuming densities of 3.20 and 2.52 g cm−3 for SiC and B4C, respectively. Five sample discs of each material were measured in this way. Samples were polished metallographically; the final step used a 1 μm diamond slurry. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterisation was carried out using a JEOL 6000 desktop SEM with a back scattered electron (BS) detector. Accelerating voltage was 10 kV, working distance 19 mm. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out on a Hitachi Gen 3 model with a monochromater using Cu Kα radiation. Generator settings were 35 kV and 40 mA. Scan range was 5°–120° 2θ, with a 0.017° step and a 4 s dwell. Samples were then etched by heating to 850 °C in air for 1 h and boiling in a Murakami’s reagent. Reflected light microscopy was carried out on a Buhler instrument. Image analysis was carried out using ImageJ software and Rietveld refinement were carried out using General Structure Analysis Software (GSAS). Data for this refinement were obtained from the international crystal structures database [25, 26, 27]. For grain size analysis, direct measurement was used, by drawing lines along the long axes of grains on representative micrographs of each material and recording the lengths of these. At least 150 grains/material were measured.

To assess the amount of SiC/B4C interfacial area in a given composite volume, an ‘edge area’ method was adopted, using BS SEM images of polished samples. All required image analysis was carried out using ImageJ software. The ‘edge area’ method used thresholding to select B4C features in a given BS SEM image to produce a simple binary image and then the ‘find edges’ tool, a 3 by 3 sobel edge filter, to produce an image consisting solely of the lines representing the SiC/B4C interfaces. B4C is appreciably darker than SiC in these images and pores are darker again than the B4C, producing three distinct shades. Thus, it is possible to select only B4C. The stages to produce this image are shown in Fig. 1. From examination of different material orientations, including through thickness, it appears that the B4C distribution is generally isotropic. Hence, the perimeter length of the B4C feature edges/unit area is related to the actual interfacial area/unit volume. The edge lines have finite thickness, and so the total edge area on the image was recorded as a fraction of the total image area. This value was converted to the interface perimeter/unit area and hence interface area/unit volume in 3D, by dividing it by the mean interface line thickness. Image smoothing was used to reduce the error from edge detection around pores. This was necessary because pores showed an appreciable contrast difference with the surrounding material, and it was otherwise impossible to use the ‘find edges’ tool without detecting pore edges. Five representative micrographs for each sample were analysed in this way.

Results and discussion

Interfacial area

Example micrographs of the type used to measure the interfacial area for the composition ranges tested are shown in Fig. 2. The interfacial area/unit volume measured in the composites is shown in Fig. 3 as a function of B4C content. The graph shows that the interfacial area/unit volume between the phases is increased both by increasing the amount of B4C and by reducing the B4C size, thereby increasing the surface area to volume ratio. Critically, the SiC/B4C interfacial area is comparable between materials with 10 wt% 7-μm B4C and 20 wt% 70-μm B4C and also to a lesser extent between materials with 20 wt% 7-μm B4C and 30 wt% 70-μm B4C. Hence, if the SiC/B4C interfacial area is important to a given property, these two pairs of materials should demonstrate similar values.

Densification

The effect of B4C content on %TD achieved in these composites after sintering for each B4C size used is shown in Fig. 4. Figure 5 shows the same data plotted as a function of the SiC/B4C interfacial area for these materials. This can be used to understand the observed relationships between addition level, size and %TD. In Fig. 5, the data are compared with the standard SiC material, which is assumed to have no interfacial area/unit volume. Though the fine B4C added as a sintering aid will generate some SiC/B4C interfaces, the method employed to quantify the interfacial area for the coarse B4C will not have selected the fine particles, due to the scale of the image used. Hence, in all materials measured, the fine B4C contributes effectively nothing to the interfacial area/unit volume.

Figure 4 shows that increasing the wt% B4C decreases the %TD achieved. Although final %TD is higher when using 70-μm B4C, it might have been expected that the finer, 7-μm B4C would have produced a higher degree of densification, as it had the greater curvature.

It is possible that the differing O content of the B4C powders is affecting densification behaviour; O contamination may affect the diffusivity at the surfaces and grain boundaries of the SiC particles during sintering. However, while the 7-μm B4C has approximately four times the O content of the 70-μm B4C, the SiC has a far higher O content than either; 0.83 wt% compared with 0.16 wt% for the 7-μm B4C. As a result of this, the total O content from the powders results mostly from SiC and does not vary much between materials. It is likely this total O content will affect the densification behaviour, since the B4C is inert, with shrinkage occurring in the SiC. Finally, the four-fold increase in O content corresponds with a ten fold increase in specific surface area. Therefore, assuming that the O is found predominantly at the surface of the B4C particles, the thickness of the O coating does not increase with decreasing particle size. Hence, the presence and amount of SiC/B4C interfaces themselves may be a more important factor than the O content of each B4C powder. This is supported by Fig. 5, which shows that the %TD decreases as the SiC/B4C interfacial area increases and this trend is constant across both B4C sizes and the reference material containing no coarse B4C. Therefore, samples with 7-μm B4C show lower %TD than those with 70-μm B4C at equal wt% addition because finer B4C generates more interfacial area. This will reduce the number of SiC/SiC particle contacts in the material. As a result of this, less mass transport which contributes to densification occurs where SiC/B4C interfaces exist. The driving force for densification is lowest when there is the greatest amount of SiC/B4C interfacial area. Additionally, it seems likely that SiC/B4C interfaces give a lower driving force for densification than SiC/SiC interfaces. This may be because of the lattice mismatch between SiC and B4C raising the energy of these interfaces and also the low curvature of the B4C particles reducing the driving force for densification of these particles. It should also be noted that the material with 30 wt% 70-μm B4C shows somewhat lower %TD than may be predicted from the trend observed in other materials. This may be because the numerous large B4C grains, which do not shrink during densification, exert a more significant pressure during sintering [28].

Given the observation that with a d 50 above ~8 μm, B4C cannot self densify [5], in these materials any B4C/B4C contacts will tend to trap porosity. However, it may be speculated that with a finer B4C, which can effectively self-densify, additional driving force for densification would be created at any B4C/B4C contacts. Further, the higher curvature of the particles may increase the driving force for densification at the SiC/B4C interfaces. These materials would therefore occupy a different regime to those in the present study.

Microstructure

The SiC/B4C interfacial area can also influence grain growth in the SiC. Example SiC grain structures from different materials are shown in Fig. 6. The large pore-like features in Fig. 6 are of a similar size to the B4C features as shown in Fig. 2 and are therefore probably caused by the removal of B4C. From comparison of micrographs before and after the etching process used, it appears that the etching tends to remove B4C features, possibly because the interfaces between the coarse B4C and the SiC matrix are weaker and so are more strongly affected by the etchant. The relationship between SiC/B4C interfacial area and mean grain length for the materials produced for the present study is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows that, across both B4C sizes, increasing the interfacial area between the phases seems to reduce SiC grain growth. With a greater SiC/B4C interfacial area, there is a greater probability that a growing SiC grain will meet a SiC/B4C interface and be physically stopped from growing. As with densification, the O content could also affect the grain growth by altering the relative rates of different mass transport mechanisms. However, as previously noted, the total O content is likely to be important and this is dominated by the SiC, so it does not vary much.

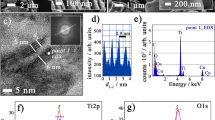

Given that the addition of B4C typically reduced the observed grain growth, it was hypothesised that it may also affect the SiC polytype composition in the sintered body. Example XRD data used to analyse the polytype composition in these materials are shown in Fig. 8.

The effect of increasing interfacial area between the two phases on the vol% 4H formed, as determined by XRD and Rietveld refinement, for materials sintered at 2125 °C, is shown in Fig. 9. This graph shows that less 4H is observed as the interfacial area between the phases increases, which is also when there is less grain growth. As with other properties, this trend also continues to the standard SiC with no coarse B4C. The error in this measurement was determined from the estimated error produced in the model. The vol% B4C in the material has also been calculated in the refinement for all materials tested and compared with the known value from the starting mass ratio of the powders. This indicates that there may be a systematic error present in the refinement data, since the vol% B4C in the material estimated by the refinement model is consistently lower than the known true value. This may result from the disorder within the B4C structure causing uncertainty when fitting of the crystallographic data using existing structure models. Analysis of micrographs used to determine interfacial area in the sintered materials shows area % B4C consistent with the theoretical volume % that should be present based on the wt% added to the powder blend, assuming the materials are isotropic. Therefore, the refinement model is definitely inaccurate for the B4C. However, the refinements of all six materials tested are self consistent, having been analysed using the same B4C structure file.

An increase in transformation to 4H with increased grain growth has been previously observed for LPS α-SiC [19]. From comparison with Fig. 7, increase in vol% 4H corresponds to increasing grain length. This may be because the growth mechanism producing the larger SiC grains involves a transformation from 6H to 4H. However, the present system would normally be expected to give solid state sintering with no liquid phase present. It is possible that small volumes of a liquid phase may have formed, possibly a Si–B–C eutectic, which is believed to cause abnormal grain growth [13], or alternatively that the solid state grain growth mechanism also involves a polytype transformation. While further work would be needed to determine whether this is the operative mechanism in the present study, there does seem to be a correlation between grain growth, amount of 4H formed and the interfacial area in the material.

Concluding remarks

This study has examined the effect of interfacial area/unit volume, a quantified microstructural parameter, on the sintering behaviour of SiC/B4C particulate composites. The following conclusions can be reached:

-

The amount of SiC/B4C interfacial area in a composite has a controlling effect on the microstructure evolution of these materials.

-

Densification is inhibited by SiC/B4C interfaces at the sintering temperature tested.

-

Increased SiC/B4C interfacial area reduces the grain growth observed in the SiC matrix, possibly by physically impeding the growing SiC grains.

-

Increased interfacial area correlates with decreased transformation of SiC from 6H to 4H during sintering, in parallel with reduced grain growth.

References

Kuzenkova MA, Kislyi PS, Grabchuk BL et al (1979) The structure and properties of sintered boron carbide. J Less Common Met 67:217–223

Karandikar PG, Wong S, Evans G et al (2010) Microstructural development and phase changes in reaction bonded boron carbide. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 31:251–259

Pittari J III, Subhash G, Trachet A et al (2015) The rate-dependent response of pressureless-sintered and reaction-bonded silicon carbide-based ceramics. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 12:207–216

Vandeperre LJ, Teo JH (2014) Pressureless sintering of SiC–B4C composites. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 34:101

Schwetz KA, Grellner W (1981) The influence of carbon on the microstructure and mechanical properties of sintered boron carbide. J Less Common Met 82:37–47

Padture NP (1994) In situ-toughened silicon carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 77:519–523

Stobierski L, Gubernat A (2003) Sintering of silicon carbide I. Effect of carbon. Ceram Int 29:287–292

Wereszczak AA, Lin H-, Gilde GA (2006) The effect of grain growth on hardness in hot-pressed silicon carbides. J Mater Sci 41:4996–5000. doi:10.1007/s10853-006-0110-z

Hamminger R (1989) Carbon inclusions in sintered silicon carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 72:1741–1744

Jung CH, Kim CH (1991) Sintering and characterization of Al2O3–B4C composites. J Mater Sci 26:5037–5040. doi:10.1007/BF00549888

Lin X, Ownby PD (2000) Pressureless sintering of B4C whisker reinforced Al2O3 matrix composites. J Mater Sci 35:411–418. doi:10.1023/A:1004715300441

Górny G, Rączka M, Stobierski L et al (1997) Microstructure-property relationship in B4C–βSiC materials. Solid State Ion 101–103:953–958

Stobierski L, Gubernat A (2003) Sintering of silicon carbide II. Effect of boron. Ceram Int 29:355–361

Shaffer PTB (1970) Solubility of boron in alpha silicon carbide. Mater Res Bull 5:519–521

Magnani G, Beltrami G, Minoccari GL et al (2001) Pressureless sintering and properties of alphaSiC–B4C composite. J Eur Ceram Soc 21:633–638

Shih CJ, Meyers MA, Nesterenko VF et al (2000) Damage evolution in dynamic deformation of silicon carbide. Acta Mater 48:2399–2420

Groth B, Haber R, Mann A (2014) Raman micro-spectroscopy of polytype and structural changes in 6H-silicon carbide due to machining. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 12:795–804

Sigl LS, Kleebe HJ (1993) Core/rim structure of liquid-phase-sintered silicon carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 76:773–776

Zhou Y, Tanaka H, Otani S et al (1999) Low-temperature pressureless sintering of alpha-SiC with Al4C3–B4C–C additions. J Am Ceram Soc 82:1959–1964

Tanaka H, Zhou Y (1999) Low temperature sintering and elongated grain growth of 6H-SiC powder with AlB2 and C additives. J Mater Res 14:518–522

Tanaka H, Yoshimura HN, Otani S et al (2000) Influence of silica and aluminum contents on sintering of and grain growth in 6H-SiC powders. J Am Ceram Soc 83:226–228

Tanaka H, Hirosaki N, Nishimura T et al (2003) Nonequiaxial grain growth and polytype transformation of sintered α-silicon carbide and β-silicon carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 86:2222–2224

Lee SK, Kim CH (1994) Effects of α-SiC versus β-SiC starting powders on microstructure and fracture toughness of SiC sintered with Al2O3–Y2O3 additives. J Am Ceram Soc 77:1655–1658

Gurland J (1967) A study of contact and contiguity of dispersions in opaque samples. In: Elias H (ed) Stereology. Springer, Berlin, pp 250–251

Morosin B, Mullendore AW, Emin D et al (1986) Rhombohedral crystal structure of compounds containing boron-rich icosahedra. AIP Conf Proc 86:70–86

Bind JM (1978) Phase transformation during hot-pressing of cubic SiC. Mater Res Bull 13:91–96

Capitani GC, Di Pierro S, Tempesta G (2007) The 6H-(SiC) structure model: further refinement from SCXRD data from a terrestrial moissanite. Am Miner 92:403–407

Bordia RK, Scherer GW (1988) On constrained sintering-III. Rigid inclusions. Acta Metall 36:2411–2416

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to acknowledge EPSRC and Dstl for funding this work, Morgan Advanced Materials for provision of equipment and expertise and Dr. Julia Percival for assistance with the GSAS software. This work was carried out as part of an Engineering Doctorate Programme in Micro- and Nano- Materials and Technologies at the University of Surrey, grant number EP/G037388/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, T., Yeomans, J., Smith, P. et al. Effect of interfacial area on densification and microstructural evolution in silicon carbide–boron carbide particulate composites. J Mater Sci 51, 353–361 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-9384-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-9384-3