Abstract

The relation of social ethics to knowledge production is explored through a study about academic research enquiry on minoritised and racialised populations. Despite social change related to migration and ethnicity being a feature of contemporary Northern Ireland, local dynamics and actors seemed under-studied by its research-intensive ‘anchor universities’. To explore this, a critical discourse analysis of published research outputs (n = 200) and related authors’ narratives (n = 32) are interpreted within this paper through conceptualisations of consciousness. Insiders’ perspectives on the influences and structures of the research journey demonstrate the ways in which research cultures (mis)shape the politics of representation, authorship and ethicality. Societal and political disregard for the new publics, reproduced within universities’ hidden curriculum, has been negotiated and to some extent resisted in the research practices of those marginalised (such as women academics), those entering the system (migrant academics), and those local-born whose referential frames were developed external to local universities. Of concern is that the few research enablers were characterised by techno-rationality and doublespeak, impoverishing the depth of theorisation, complexity and intellectual debate necessary for challenging the existing dysconscious racism and xenophobiaism of the social imaginary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Contextualising the Study

Under-study, omission, and problematics with dissemination and authorship can create intergenerational legacies on schools of thought. Concerned with the continued production of untroubled racist thinking and knowledges in Western universities (Eze, 1997), interpretations offered in this paper are informed by a critical review of the state of critical consciousness within academic enquiry produced by anchor universities about their local populations who are marginalised due to racism or xenophobia.

The academic research practices are of a countryFootnote 1 positioned within the United Kingdom (UK) and at the periphery of western Europe – that of Northern Ireland (NI). A dominant discourse is that NI’s population is monoracially ‘white’ and ‘Christian’, despite recent socio-demographic changeFootnote 2; and characterised as ‘post-conflict’, with continued ‘tribal’, ‘ethnic’ loyalties between two Protestant/ Unionist and Catholic/ Republican divided ‘communities’ (Miller, 2014). More controversial are references to its settler colony history, and prior relations and material benefits from the British empire. Particularly avoided are considerations of how “the recategorization of the Irish as white and the subsequent change in positioning on the racial ladder came at a price of subscribing to white supremacy” (Joseph, 2022, p. 79; see also Peatling, 2005).

During NI’s period of violent conflict (‘The Troubles’), solidarities were crafted with global populations’ collective struggles for equality and civil rights, including those suffering from partition and racism in South Africa, Palestine and the United States of America (Peatling, 2005). Academic research and mobility exploited these, establishing NI as a hub for multidisciplinary scholarship of peace, conflict and security since the end of the Cold War. Although local academics avoided the subject of violent and social conflict between the two dominantly-positioned groupings during The Troubles (Taylor, 1988), that has received considerable local and international scholarly attention with funding flows from the UK, the Republic of Ireland (ROI), the European Union, and the USA. However, these have not carried over to addressing, researching nor educating about racism within the borders of NI (Crangle, 2018; Hainsworth, 1998; Irwin & Dunn, 1997; Michael, 2017), despite media attention and the collective activism of affected groups (Gilligan, 2022; MPs on the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee, 2022).

Understandings of “the forces that can shape conceptions of national insiders and outsiders” and “how conceptions of nationality, race, culture and ethnicity have intersected to shape attitudes towards migrants” (such as by Crangle, 2023 and others) in NI society, are extended in this paper to such (mis)shaping of consciousness within academia. This contributes to scholarship about the “messiness” of ethicality (101 Cliffe & Solvason, 2022) in the hidden curricula of the formation of academic subjectivity (Durán del Fierro, 2023), and how oppressive interests may be accepted, reinforced or resisted in academic practice. Cognisant of the dangers of exceptionalism about NI, and also the UK’s current methodological nationalisms about racism which exclude cross-context comparisons and accountability (Gilligan, 2022), the paper’s conceptual framing draws from the concerted challenges posed by scholars of EuroAmerican universities to institutional ‘ethics of opacity’ (Walker, 2011). Such deidealisation is required to question how academic consciousness, integrity and practices are impacted, and may be undermined, by thinking within the structural and institutional context, and broader organisational influences of the research environment (Kennedy et al., 2023).

Conceptualising Consciousness

‘Consciousness’ and ‘conscience’ could arguably be organised along a continued of criticality, as per Fig. 1. The former’s psychosocial awareness of relations, allegiances and commitments are the tacit curriculum of social formation. The latter’s moral awareness serves as a basis on which individuals or groups ground obligations to in/action against wrongs (from which ‘prisoners of conscience’, ‘conscientious objector’ et cetera relate). However, such a polemic schema would be mis-representative of the complications of interests within the social institution of the university, where criticality cannot be assumed to always-already extend to injustice, and to racism. Individuals, groups and institutions may consciously and intentionally cement, exploit, exult and further their advantages within systems of whiteliness, eurocentricism or white supremacy; and may accept projected or adopted racial identities on themselves (Allen, 2018) even when experiencing “double consciousness” (Du Bois, 1903). The latter’s “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity”, has been systematically reproduced through the White epistemic gaze of Western academia’s “inner eyes” (Wynter, 1994, p. 44) in academic functions - research, education and Third Mission - including academic citizenry.

Decontextualised, ahistorical, deracialised and depoliticised conceptual framings, which accept and maintain given conditions as ‘natural’ in the human-to-human-ecological ‘order’, underpin dysconsciousness. Such determinism absolves individuals and institutions of culpability and agency, disengaging collective consciousness of the sociological imagination (Mills, 1959). Thus, rather than an “absence of consciousness (that is, not unconsciousness)”, dysconsciousness is the habitually impaired “distorted way of thinking” (King, 1991, p. 135) where immoral framings are maintained by epistemologies of ignorance (Mills, 1997) about racism. These are organised by the past and present White Racial Frame (Feagin, 2013, p. 11) which envelops “‘a belief aspect (stereotypes and ideologies); cognitive elements (including narratives); and an inclination to action (to discriminate), which’ [is a] disinclination to act against racism”. Ideological justifications for the racial order can become internalised to the point where both institution and structural racism in academic settings are not only uncontested but often unrecognized (Anderson et al., 2019). The political, social, material, pragmatic and affective hold of the false ontology of whiteliness in the ‘Racial Contract’ (Mills, 1997) thereby remains unchallenged by its beneficiaries, as do the advantages gained by subordinating and denying personhood of ‘Others’. Such dysconscious has been evoked through metaphors of un-seeing, including blindspots (Gilligan, 2022; Rankin-Wright et al., 2020), colour-blindness (Ryan et al., 2007), refraction (Feagin, 2013), opacity (Walker, 2011), veils (Du Bois, 1903) and shrouding (Feagin, 2013).

Unaccustomed to even thinking of questioning such norms and privilege, those in positions to engage and develop consciousness through the functions of formal education, bypass ethical judgment (Anderson et al., 2019; King, 1991; Rogers, 2021). Pertinent to this study’s concerns, the abdication of moral responsibility and critical agency of both the institution and academic citizens, is said to be enabled by UK universities’ adoption of ‘unconscious bias’ training for ‘equality, diversity and inclusion’ (EDI). What the training targets are psychological intentions, individual attitudes and practices, “rather than ideological values and their imbrication with white institutional power” (Tate & Page, 2018, p. 147), thereby misrepresenting how structural racism in the UK “is neither unconscious nor is it unmotivated” (Beckles-Raymond, 2020). Individuals’ and collective’s commitments to dismantle “White normative practices, systems of thought and affective regimes that maintain and recycle anti-Black and people of colour racism” are undermined (Tate & Page, 2018, pp. 144; 146). This is the paradox of social ethics within “aversively racist organisations – like universities – built on foundations of equality” (ibid.).

Critical consciousness is related to, though also distinct from, many of the histories of conceptualisation of moral conscience (Liu, 2015) and anti-racism. Freire (1974) was a proponent of working through non-formal sociopolitical education to catalyse collective agency for transformative change. The active process of ‘conscientização’ (conscientisation) is one of “unveiling” conditions that are contradictory (whether social, political, economical, etc.) for the purposes of social justice, that is the remedy of oppressive consequences of social ills (Skelton, 2023). The process towards such intentional action, requires the dual intervention of critical reflection and motivation (Diemer et al., 2016). However, interest convergence (Bell, 1980) with the Racial Contract (Mills, 1997) has made apparent that holding critical consciousness about one injustice may not correspond to another. In UK academia, this has been demonstrated at the individual level in the principle-implementation gaps of academic ‘allies’ (Tate, 2023); and, systemically, in the racialised and classed benefits resulting from sectoral interventions purportedly for all academic ‘women’ (Bhopal & Henderson, 2021). Collective agency and ‘white privilege’ become de-radicalised when the fragility of ‘white’ individuals (Leonardo, 2004) and (un)conscious bias (Tate & Page, 2018) is centred. Similarly, dysconscious racism and dysconscious xenophobiaism (Okhremtchouk & Clark, 2018) may be the foci of distinct or intersecting study and action. Recent shifts, within the study of UK universities, incorporating consciousness of the impacts of geopolitics on universities’ functions have been influenced by non-UK based scholars working at the intersection of critical geopolitics and higher education studies (see, for example, the special issue edited by Moscovitz & Sabzalieva, 2023) who question the operationalisation of Enlightenment ideals of progress, ‘civilisation’ and modernity, through the control of time, space, knowledges, resources and bodies which reinforce colonial and neoliberal regimes. A reoccurring concept within such studies is challenging assumptions of institutions as “powerless victims of the state” (Vlachou & Tlostanova (2023, 214), and their role of complicitly, co-option and resistence to (re)producing and/ maintaining geopolitical inequalities. What is notably absent from UK institutional discourses about critical consciousness are practices of the virtues fundamental for coming to critical consciousness - resistence, humility, dialogue and love.

To challenge complacency in contexts where ‘post’-racial discourses obfuscate continued oppression, inequality and injustice (Tate & Bagguley, 2017), scholars are tackling how dysconscious racism is inculcated through the false ontology of whiteliness “as utterly benign in its naturalness” (Yang 2015 in Tate & Page, 2018, p. 146). This requires the stronger framing of ‘anti-racism’ to reveal how institutional discourse about itself often serves to “mislead, distort, deceive, inflate, circumvent, obfuscate” (Lutz 1990, 255 in Smith, 2021) structural racism. By operating at odds with its espoused messages, thought is both concealed and prevented, and thereby responsibility denied, avoided or shifted (Smith, 2021). Reflecting on anti-racism’s containment by UK universities’ minimum compliance to legal obligations, such as ‘equality’ law, editors of a related special issue held that

It is not a failure produced by anti-racists but is one that was a direct result of its institutionalization and colonization as ‘equality and diversity’ after it had been stripped of its potential for critique and action. After all, it is impossible to allow unfettered institutional access to something which has such a fundamental critique of that from which you benefit and that which ultimately is not in your interest to change. (Tate & Bagguley, 2017)

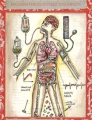

In contrast to simplistic conceptualisations, the politics of consciousness within such doublespeak in the contemporary Western university is visualised through bricolage in Fig. 2. It playfully references the archetypal janiform figuration which emerges within ancient and contemporary culturesFootnote 3. Within scholarship, the janiform signifies unresolved complexities at play – including the contrariness of discourses (such as doublespeak of integration and diversity in the UK and EU, see Anthias, 2013); relations between that seemingly reified and monolithic (such as Hughey, 2009 on racial identity); and ethical predicaments of assigned leadership of public authority (positioned between organisational rationality and public perception, formalism and utilitarianism, Brady, 1985). This is more than the duplicity and hypocrisy of practicing the communication of opposing meanings. The Janus head also embodies liminality: eyes or mouths are displayed wide open to audiences with influence from the past, including the ancestral, on one side; and of the future-present, on the other. Temporal ways of seeing are mirrored, often visualised as a mask; discourses and interests are mimicked in the promises and assurances that are mouthed. Below, I have visualised the affective magnetism and material power of the fictions of the ivory tower as the embodiment of a grotesque, zombie-like pastiche.

Reckoning, dismantling and restitution have been re-asserted through calls to decolonise socio-cultural infrastructure, including that of universities, academic disciplines and the curriculum. Commitments to radical alterity within decolonial scholarship include recognition of plural ways of being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007), living, thinking and spaces which are present despite their construction as absent (Mbembe, 2016) by the dominant knowledges and modes of representation incommensurate with the colonising interests and disciplining logics of the modern, Western university. Decolonial consciousness beckons to a future repaired, and thus not replicating dominating cycles and relations of violence and harm. Operating beyond the bounds of the EuroAmerican academy, Mbembe (2017, p. 178) argues a dual approach is needed for a new politics and ethics of responsibility for researchers who “must make a break with ‘good conscience’ and the denial of responsibility”. Within such conditions, “academic integrity” as “a continuous struggle that involves constantly navigating difficult ethical choices” (Gewirtz and Cribb, 2020, p. 804) calls forth ethico-political injunctions. Social ethical judgement, inherent to critical consciousness (Heaney 1984 in King, 1991), requires disruption of epistemic enslavement to the centred Western, white (hu)man as the ‘self’ against which all are othered. Differing traditions practice this disruption by: occupying scholarship from the standpoint of the subaltern; affirming the collective force of identity politics or complicating the privileging within their descriptive content (Crenshaw, 1991); and calling for shared responsibility of reparative relationality (Zembylas, 2024).

However, scholars warn that many attempts to ‘decolonise’ recently in the EuroAmerican academy have been limited, distorted, perverted, or coopted (Doharty et al., 2020), including the relation between decolonialisation and racism (Hundle, 2019), in ways which evade and undermine transformative justice. Institutionalised machinations of injustice, including the distorted sufficiency of meeting institution’s minimum ethical compliance standards, serve to maintain dysconsciousness about the university’s “opaque sites and repressed knowledges of colonized peoples” (Winter 2011 in Zembylas, 2022, p. 95). The limits on the conditions of possibility for the projects of decolonisation in the EuroAmerican academy, coupled with the renewed urgency of this time, has led scholars to reassert the counter-force of anti-racism (Hall et al., 2023; Tate, in press) and counter-hegemonies (Singh & Leonardo, 2023).

Aware of such conceptualisation of the conditions of (im)possibility, in this paper I offer a reading of the state of consciousness within academic research norms in Northern Ireland (NI) by probing how existing outlier practices of knowledge production reinforce, evade or resist dominant frames.

Methodological Notes

Five years before commencing this study, having relocated from South Africa to NI, I experienced stark differences in the sociological imagination and appetite for change within university functions and spaces, and the internal-external relation of academia to its publics. While imperfect and unresolved, collective conscietisation has been characteristic of the post-apartheid university milieu, including ‘institutional culture’ (Keet, 2015) and the responsibilitisation of academic citizens. In contrast, feedback from within the NI institution on my first UK research application was to remove ‘social justice’. Its associations with international development, philanthropy and activism would seemingly undermine my academic legitimacy, already tenuous as a person from the Global South. I became increasingly aware of the influence and, in due course, the constraints of uncritical and compliant assessment literacy within NI to UK funding regimes. Simultaneously, as a ‘blow in’ I was brought into proximity with similarly positioned outsiders, framed locally as ‘ethnic minorities’. I was elected to a local civil society collective, the Migrant and Minority Ethnic Thinktank, whose council was peopled by those well-informed from local, lived, professional and voluntary cultural work experience. In time, as discussions of the relationship of universities to local struggles with power arose, we formulated the study which informs this paper.

Methodologically, I was guided by the tenets of critical race theory (CRT), wherein sources that differ (in this case, the outcomes and counter-stories of researchers) are drawn upon to reveal the operationalisation of the White Racial Frame “in routine legitimation, scripting, and maintenance” (Feagin, 2013) of research within the academy. As a study of culture, representation and power, critical discourse analysis (CDA) enabled interpretations of the research texts (Kunisch et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023) and narratives of their authors as artefacts to read the con-text askew. CDA and CRT have been productively brought together to study racism in UK HE (Smith, 2021).

Analysis involved dialogical oscillation between theory (the conceptualisations of consciousness in academia outlined above) and the different sources of data. From the institutional repositories, published research items were collected which focused on NI’s new publics (Fig. 3). Data coding of the 200 items included quantitative indicators, terms and excerpts, organised by categories and subcategories including publication date; type; authorship order, affiliations and demographics; disciplines; subject matter; methodologies (including orientation, sources, methods, ethics-related content including positionality statements and reflective commentary, funding); wording used; and recommendations for research and for impact (see Belluigi & Moynihan, 2023, pp. 11–12). Initial interpretations informed report-and-respond discussions with 2 research development officers and 3 members of a local civil society organisation.

The published items were authored by 247 academic citizens of various positions and contracts. Those affiliated with Northern Irish universities at the time of the items’ publication were contacted via email, of which 32 elected to participate through semi-structured interviews (25) with the author or through anonymous responses to an online questionnaire (7) of the same 22 open-and close-ended questions. These elicited reflections about the authors’ relations to the area of enquiry; conditions during the research lifecycle (Joynson & Leyser, 2015; Moran et al., 2020); and perceptions and discourses about such research. The majority (25) produced scholarship in this area of enquiry in the past 10 years (of which 15 were active in the last five), 7 between 2014 − 2004, and 1 in the period 2004 − 1994. Analysis of their positionality is incorporated within the sections below.

Numerical indicators and pseudonymised excerpts are included herein, without indications of institutional specificity, cognisant of the significant professional risk to the participants and author. For the full description of the research process, deliberations around nomenclature, limitations and initial descriptions of the findings, please see the study report (Belluigi & Moynihan, 2023).

Interpreting the Signs

Interpretations are organised into discussions of five ‘signs’, taking the reader from what the publications revealed and omitted in their representations, to what authors of those publications shared about their experiences of the politics of participation and authorship. This includes the complexities of motivations, identifications and interests to undertake such research; their relation to public and academic data; and the risks and experiences of social sanction within what emerged as research ecology of dysconscious racism and xenophobiaism. The final section turns to the janiform nature of public and academic institutions, and participants’ concerns about the sociological imagination within and beyond academia.

In this way, the analysis exposes value conflicts often concealed between, against and across the broad domains (Helgesson & Bülow, 2023) upon which research ethics and integrity are applied, including the researcher, research community of practice and contextual character traits and values; the research itself; and research-related institutions and larger influential systems. The mapping of conceptualisations in the section above, provides a loose referential frame for ‘seeing’ the signs of the differing forms of dys/consciousness at micro- and macro-levels through the shaping, constraining and enabling, and resistance within academic research practices.

Under-Study and Under-Funding

The first finding of relevance to this paper was the confirmation of under-study of this area of enquiry by those within the academy. Institutions’ repositories recorded 209 items from 159 projects. Annual increase is discernible from the first publication in 1994 (see Fig. 4); however, the absolute numbers remained below 23 items per annum, from a range of disciplines. Moreover, over half (51%) were outputs for the purposes of translation to non-academic audiences, rather than academic knowledge dissemination. While this shows that ‘impact’ was a high priority in this area of enquiry, it raises concerns about sustainability and the limited contribution to local and wider knowledge. Participating authors confirmed that “it is considered to be an outlier in relation to the general culture of research” in NI research-intensive universities [UI1021]. British sociology has faced significant critique for its omission of interest in the descendants of non-Western ‘Others’ (Bhambra, 2007).

Tenders for funding were the main incentives for this area of enquiry, reflected in the echoed dynamics of production in the above figure. Pressures of ‘grant capture’ for maintaining academic careers characterised the realities of practicing within this context. The majority of researchers engaged in only one project to do with this area. Interviews with such authors revealed many did not see themselves as legitimate authorities - neither in this area of enquiry generally nor in local complexities, despite having undertaken research thereof. Thus, the research questions and methodologies were often determined by the interests of the funders rather than academically-informed researchers or supposed beneficiaries, despite appearing to be ‘needs’ related. Funders supported empirical ‘evidence’ for solutions to problems in policy or services, with a limited social inclusion imaginary, akin to new philanthropy (Ball & Olmedo, 2011), which thus engendered such outputs and not engagement with more complex issues or theory-generation.

The Politics of Participation and Authorship

Content from the outputs were analysed for the politics of participation between researcher-researched in the knowledge production processes. This concept recognises that power relations pervade academic knowledge processes and production, through practices that order how subjects, scientists, the technologies of publication and their consumers are positioned to fit together. Scholars have raised such questions in terms of research concerned with participatory action research and with research on sustainability (see for instance Jordan & Kapoor, 2016; Fritz & Binder, 2018), noting the dimensions of structures, actors and processes. To raise questions about the ethics of such relations in this study with recognised minorities, what was documented within the publications was extracted and mapped along a continuum: being positioned as object, as participant, acknowledged as a partner, or attributed a role as author. (A further consideration about such politics, is the politics of representation that relate to capture and categorisation in data, which are discussed in the section ‘problematics with data’ below.)

The majority of outputs (99) positioned those represented as objects of study. This included secondary sources such as public data sets, and studies about the perceptions, practice or policy of dominantly-positioned populations that related to minority populations. Participating authors revealed there was a dearth of valid public datasets and missing data (discussed in more detail below). Considerable barriers to access existing data sets were the norm (Patel, 2020), with gatekeepers justified in relation to “sensitivities” and, more recently, to the risk of disclosure with increasing privacy regulations around ‘personal data’. The problems and deficits to do with administrative and longitudinal public data sets was provided as one of the main reasons why primary data was generated.

Thus, a similar proportion of outputs (94) involved primary data generation from, and in some cases with, those minoritised. Such a high participation rate was a surprising finding of the analysis. However, even with those projects, the dynamic was characterised by participating authors as “extraction and appropriation” [UI1001]. One of them utilised intentionally dehumanising terms to mimic researchers’ conceptions of the participants,

when ethnic minority species or migrant species are approached it is to refer participants only, not to influence the design or the outcome of the research. And somehow that’s seen as more neutral and objective, but it isn’t. You know, it’s actually excluding some of the key expertise” [UI2003]. [emphasis added]

Few items (7) acknowledged minoritised individuals or groups who had acted as gatekeepers or advisors. This contrasted to the importance they were ascribed in enabling the research, by participating authors in interviews. As discussed later, this public omission of relation with minorities and with advocacy groups, strategically increased perceptions of the research team’s objectivity and legitimacy for the local dominantly-placed readership.

Non-academic ‘ethnic minorities’ or ‘migrants’ were absent from co-authorship; however, authorship was analysed to ask the question of their representation within the pipeline to positions of intellectual authority within the NI academy. Analysis of attributed authorship revealed proportions of female (60%) and migrant/ ethnic minority (15%, of which 75% were female) authorship that were larger than their representation in the staff composition. To compare this with the socio-demographics of the academic staff composition of NI’s universities, in 2020 NI had the lowest representation of female academics (44%) and of racialised minorities (11%) of the UK’s devolved nations (Belluigi et al., 2023), with even less local representation when intersections between gender, race and nationality are acknowledged.Footnote 4 While authorship by researchers of colour had increased, the actual outputs were low (see Fig. 5). Of concern is that only a single co-authored output was led by an academic of colour, and that female authors of colour sole-authored doctoral dissertations only.

Such positioning is read against the intersections of ethics, accountability and non/academic relationships (Vander Kloet & Wagner, 2023) in the next section.

Interests and Motivations in Undertaking the Research

As outlined in the conceptualisation of consciousness at the beginning of this paper, the relations between consciousness, identification, interest and motivation, and academic cultures are important considerations. Acknowledging the marginality of this area of enquiry locally, the question schedule provided conditions for participants to reflect broadly about internal-external motivations to undertake the research. Participants responses drew from personal, professional, disciplinary, and political motivations. We analysed these responses in relation to the content they had included on ethics and positionality in the published outputs. Both are discussed within this section.

It was found that the few participating authors who explicitly expressed being motivated by their critical consciousness, situated that interest within research topics which were specifically about health, social, economic and educational injustices, or socio-cultural injustices in their academic work more broadly. For many, neglect of the under-studied populations had created “evidence gaps” which were easy wins for when responding to policy-aimed commissioned calls to tender. A number were self-critical of tenderpreneurial habits (Sebola, 2023) normalising exploitation for the private gains of meeting key performance indicators for career advancement. They argued that “if something is being overlooked and marginalised it’s the role of social sciences to illuminate inequalities in our society; that’s why we kind of join the field and not become entrepreneurs” [UI1004]. Others were less self-critical, characterising the terrain using colonial terms, such as a “frontier”, to be entered into with the aspiration to “carve out a niche in a sense and say, ‘well nobody else has done this, I’m doing it’” [UI1012]. However, participants raising these insights contrasted such hopes - whether for career gains and/or for social impact – with the considerable risks and costs they brought, as explored in the last ‘sign’ of the paper.

Participating authors revealed that some of the motivations were necessarily strategic. Sexism, xenophobia and racism within the NI academy had, for some, created sutured spaces and closed networks barring access to research about majority-placed groups and related issues. The high proportion of translation-related items was linked to the sex of authors by a participating research development officer, who noted that attendance at related training “tend to be 90% women” [RD001]. This increased access to small “pots of money” for translation was less risky and time-intensive than large research funding, which has been shown to disproportionately reward ‘male’ and ‘white’ academics (UKRI, 2021). UK research funding successes evidence award gaps for women generally and applicants of colour specifically, affecting Black primary investigators (1% of applications awarded funding in 2020) and fellows (< 5 awarded funding in 2020) (UKRI, 2020), and female academics of colour (2% of primary investigators were successfully awarded between 2018 and 2022).Footnote 5

Migrant academic participants revealed that chances of funding success depended on collaborations with an established non-foreign-sounding ‘name’, particularly male. “I have to basically do all the work and attach myself to somebody like that, who then ends up getting the credit and we’re not able to disrupt those cycles” [UI1001]. Such politics of academic mobility have been noted as a feature of academic cultures without rules preventing inbreeding (Seeber et al., 2023). Strategies to negotiate the hostile response of local gatekeepers was “to try and get academic allies on my side… if my name or my voice isn’t opening a door, maybe one of theirs might instead” [UI2002]. Similarly, respondents suspected that invitation by ‘white’ and/or male leads to co-author was driven by optics “to meet the gender parity requirement” [UI2003], rather than commitments to gender or racial justice in science.

None of the participants described coming to critical or race consciousness from their exposure within a NI university. The dearth of formal higher education curricula on related topics were raised by authors, and linked to the dysconsciousness of the majority culture: “that’s giving a good indication that it’s not seen as, I wouldn’t say that it’s unwelcome, it’s just made invisible” [UI1004]. Those with relative agency for curriculum development in ‘teaching and research’ contracts, described barriers to infusing such research in their curricula. Colleagues were described as “not interested in it, [and] they assumed the students would not be. And if there is kind of a symbol for the gaps between the universities in what they should be doing and what they are doing, I think that’s it” [UI2003]. Prior to 2020’s BlackLivesMatter, local-born students perceived the subject to be “irrelevant”. Repeated exposure to collective disinterest from students and colleagues, impacted the curriculum content of migrant academics’ teaching, till “race became just less and less until that’s not really in there anymore” [UI1018]. Reduced agency and misrecognition of migrant academic expertise is a studied problematic for democratising curricula in England too (Rao et al., 2019).

Exposure to scholarship within external academic contexts had cultivated critical race consciousness for some: “where I grew up was work by people like David Gillborn and Heidi Mertz … and [I] saw that there was a need to do that kind of research in NI” [UI1015]; “early studies like Paul Hainsworth’s (1998) edited collection ‘Divided Society’… thinking about the question of where people from these backgrounds fitted into Northern Irish society” [UI1012]. Professional and voluntary experience was also catalytic: “that triggered let’s say my decision back then, I was a professional working in projects” [UI10114]; “I suppose the starting point is my kind of professional background as a teacher” [UI2001]; “I benefited greatly from not ever losing touch with that NGO side of things… that dimension been absolutely vital to my own life and work” [UI1003].

Those from NI or ROI who identified with the plight and experiences of those minoritized and those migrant to the island, articulated a sense of suffering, injustice and resistence within their familial autobiography: “my parents’ generation, my grandparents, they were treated in this place like they were 2nd, 3rd, 4th class, as if they didn’t belong. And where I came from there was always a sense you had - and I’ve always then felt that sense of obligation towards anyone in those sorts of situations” [UI1003]. Intergenerational collective memories and shared lived experience of racialisation, emigration or forced displacement were catalytic for non-locals: “Having family who are from a refugee context also gives me an incentive to get involved” [UI1021]; “my family were a hundred years ago, refugees” [UI1020]. Most of the migrant academics had not intended to conduct local research prior to emigrating, becoming compelled once witnessing problematic representations within society left unchallenged by scholarship.

For many, identification with the populations they studied was a motivation. Almost a third (31%) identified as migrant academics, including those from within ROI, UK and the EU, and external. The intersection between migration and ethnicity informed the perception and the experience of being positioned as ‘other’, and in turn, consciousness and identification with those othered in NI. Within NI’s climate, 50% of the participating authors self-identified as ‘ethnic minorities’ while acknowledging that ‘officially’ only 9% would be categorised as such, because NI utilises the term ‘ethnicity’ as proxy for those racialised as ‘other-than-white’ (Belluigi et al., 2023, pp. 66–69; GOV.UK, 2021). Most saw ethnicity in far more nuanced and distinct ways. Some acknowledged that those perceived to be ‘white’ and Christian would be given more access, and experience less estrangement and discrimination, than those racialised as Black or assumed Muslim.

The position of alterity was highlighted as intellectually generative. Some of the participants drew on notions of the emigree consciousness of ‘the stranger’ who ‘call[s] into question the rules of functioning’ (Ladson-Billings, 1998, p. 22) and places the ethical injunction as for the hopeless (Said, 1993).

If you talk about the capacity or the positive capacity then from migrants, migrant academics, ethnic minority migrants in this space, in this Northern Irish space, then it’s definitely about topics that probably are not tackled and not talked about enough by majority, settled academics [UI1014].

The conditions for practicing such exploration within the university was however undermined by interactional exclusionary responses and practices by those dominantly-placed, which seemed particularly negative for ‘academic migrants’ (Rostan & Höhle, 2014), i.e. those not educated within the UK or ROI.

I don’t think there is an inclusive research culture [for] a person who is a staff member whose education is not in the UK system at all, who looks at research, looks at different aspects of research and dissemination in a different way [UI1006]

Such exclusion was compounded because this area of localised enquiry was constructed as “controversial” or “sensitive”. Even for majority-placed academics, NI’s risk-aversion has been recognised as methodologically challenging (Brewer, 1990; Feenan, 2002). One participant described how “as soon as you offer space for controversial discussion… you run really into trouble because you are not only the outsider, but you are to a certain degree then this kind of stranger and minority and migrant as you have it” [UI1014].

However, such insights were noticeably absent from the content of most publications. Only 7 projects engaged with the complications, quandaries, dilemmas of ethical relations, the politics of representation and the positionality of the researchers - these were doctoral dissertations by authors of colour. Of the 149 projects, 117 (79%) had no reference to ethics whatsoever. Of the 32 that did, 25 referred to compliance to ethical clearance committees and the basics of ethical conduct. This was not a case of academics with power neglecting publishing self-criticality (Kinkaid et al., 2022); nor was it consistent with the disciplines of the majority of the authors (found to be uncommon in political science, for instance Jordan & Hill, 2012). Rather participants’ revealed this was standard local practice, about which some had also published (Ellison, 2017, 2017; McAreavey & Das, 2013).

They shared that limiting publicly available revelations about the writers’ locus of enunciation (Diniz De Figueiredo & Martinez, 2021) was a safeguard, adopted to reduce the possibility of the attack of bias or allegiance being raised by already-suspicious audiences. The enabling fiction of the omniscientist was maintained for legitimacy purposes, within the tenuous relations between NI’s public authorities and its publics, observed by scholars before (Knox, 2001; Taylor, 1988). The practice of avoidance has negative implications, both for transparency with readers, and engendering criticality between fellow researchers. Sadly, in interviews many acknowledged that such concerns and commitment to the community of research practice waned as their cognisance of the risks and social sanction grew (discussed more below). Newer entrants and early career researchers in the study felt such non-reflexivity left them ill-equipped; and that institutional and disciplinary procedural compliance was inadequate guides to the realities and dilemmas of actual local practice (Cliffe & Solvason, 2022).

Problematics with data

Both the public and academic sphere were characterised by problematics in critical data literacy and justice, with invalid capture, categories and accountability for those not-dominantly-positioned. The late implementation and weak policy around data collection for those not-dominantly-placed – informed by immigration law, equality acts, employment legislation – has little salience with the in/equality concerns about Catholic/ Protestant-sectarianism discrimination, and the secondary concern with discrimination against women. Similarly deprioritised are the indigenous group, the Travellers, “almost like a hidden minority” whose marginalisation “wouldn’t be seen by a lot of people as being discriminatory or intolerant or whatever, it is so engrained into our society” [UI1010]. Despite active calls from affected organised groups and international frameworks (such as the Durban declaration, UN resolutions, and the UN Decade for People of African descent, among others), there has been little rectifying activity. Policy-implementation gaps and the lack of accountability result in proportions of incomplete and missing data that are at times larger than the estimates of the non-dominantly-placed populations who “have less protection against discrimination and harassment than… in other parts of the United Kingdom” (Equality Commission of Northern Ireland, n.d., p. n.p.). Data capture was therefore experienced by NGO members as a statistical groundhog day: “you said the same thing 10 years ago, so what’s changed from the data that we gave you 10 years ago because we’re still experiencing the same thing?’ [NGO001].

Theorists in this area, encourage us to study the missing gaps in data in contexts with sophisticated regimes for data collection (Crawford, 2019; Gillborn, 2015). Onuoha (2016/18) has emphasized how our gaze as researchers should be on the “blank spots that exist in spaces that are otherwise data-saturated” which reveal “hidden social biases and indifferences” (Onuoha, 2016/2018, p. n.p.). Participants revealed the problematic assumptions which underpinned the lack of critical data literacy within public authorities in NI: “dissonance highlights the consequences of this idea - to use that phrase, ‘there’s no racism because there’s no Black people’, well actually there was. There was both, there was minority ethnic people and there was also racism” [UI1012]. The absence of care and protections for those not counted and those counted incorrectly, in the face of systemic discrimination and hate crimes, mirrors the critique Wynters (1994) articulated in societies of white supremacy, where those not racialised-as-white are emptied of life in various ways, as “no human involved”. Participating authors witnessed “bigoted” desire for erasure, “we don’t necessarily want to acknowledge that this population exists” [UI1020]. Dysconscious racism and xenophobiaism fed into patronising claims of ‘duty of care’ to justify reneging obligations to ethics of justice and representation.

there’s just an assumption that well the minority, ethnic population here is pretty small, a bit inconsequential. Or even more pernicious, there’s like an assumption, ‘Well they don’t want to be looked at, they want to keep their heads down because they experience racism and exclusion’. So it [the research] would put it more of a spotlight on them that’s going to increase problems for them [UI1004]

Tate (in press) writes about how such conditions of “anti-Black contempt means that people and theory are ignored, under-represented and erased” in UK, USA and Canadian universities. In doing so, she links Wynter’s “no human involved” to academic knowledge production, as “No-Theory-Involved”.

Another problematic is the available categories in the UK (Aspinall, 2020) which were originally created to racially segregate access to the UK (Patel, 2022). Ahistorical classifications are amnesiac about organised migrations during the British empire and decolonisation, ignoring double and triple migration. The entire continent and descendants of Black Africans are grouped together, with centuries of diaspora alluded to by distinguishing ‘Black Caribbeans’ and ‘other black background’, and segregated from those Africa-born Arabic, ‘Chinese’, ‘Indian’, and ‘white’, and from the histories of organised migration during British colonialism, home rule, and since the end of The Troubles (Crangle, 2023). Re-racialisation positions those appearing ‘white’ to pass into the dominantly-placed majority, particularly those with linguistic capital (such as from South Africa, Zimbabwe, India, the Caribbean, the Americas etc.), even without direct ancestry. This impoverishes identification, solidarity and data for research purposes, because “it matters whether or not someone is a recent immigrant with that social category, and whether or not they are an established and identify as Black British for example or Black Northern Irish, or like they’re recently arrived in which case they may have a national identification that’s more similar to their parents” [UI1007].

Referred to in 35 of the research items, the term ‘migrant’ was linked to labour, employment and often reproduced geopolitical and racialised power relations, as found in other European studies (Kunz, 2020). Those most ‘targeted’ for study were selected because of their visual or socio-linguistic alterity to the majority populations. The metaphysics of intersectionality (Bernstein, 2020) was unrecognised; rather, most often, the legislated ‘protected characteristic’ of sex was considered (46/209 items). Surprising for a context where religious difference and identification are routinely monitored and researched, when about the majority-positioned populations, and where Islamophobic and anti-Jewish attacks are a well-known occurrence-religion rarely featured (10 items). Migration scholars have argued that academics should recognise migrations’ links with religious freedom and democracy (Zanfrini, 2020).

Public data sets were inaccurately handled. Becoming invalid for analysis of the legislated differences, data sets on those seeking refuge in the different devolved nations were combined: “the central government enmeshes information on Scotland and NI… reflecting a broader picture and attitude of what’s important and what’s less important” [UI014]. Similarly, within the published items analysed, nomenclature was inconsistent and at times incorrect, despite legislated differences in rights and protections that complicated the efficacy of translation materials.

In quantitative research particularly, the norm was to exclude data from or about non-majority-placed populations. Because of the privileging of such research, the effect was that this area of local enquiry “is an aspect of university life that is not fully accepted within the gambit of research legitimate fields” [UI1021].Footnote 6 The university mirrored the self-image desired of the dominating publics and party politics of the country – reproducing the established norm of ‘white’, NI-born majority groups as the exclusive local interest for local-born academics and NI institutions; with complexities of race, migration, social relations et cetera mattering when in contexts beyond NI borders. This impacted the validity of both data and knowledge production:

There are a few studies, but they are not really focussing on ethnic minorities, immigrants per se and even if they have in their data set, they don’t ask the questions that are relevant for ethnic minorities, where they ask questions about Protestant Catholic relationships and other more generic questions. But not for instance their experiences of discrimination, how do they feel about the conflict as an immigrant as a third party, right?… even if they are in the data set, then their experiences are not centred in these data sets. [UI1008]

Capacity development, to handle the minority-majority dynamics of the context, and particularly racism and its intersections with religious intolerance, was absent from the universities: “it became clear to me that part of this gap was nobody was really trained to incorporate the experience of the minority ethnic groups” [UI1004]. This extended from methodological gaps in to the uncritical reproduction of academic-public relations.

it always struck me that in NI these universities that talk about having very strong links actually didn’t want to create them as part of their professional work. It expected them to happen as a result of people’s personal relationships and that is not a recipe for integration. That’s a recipe for segregation. [UI2003]

The role played by institutions were technocratic quality assurance, rather than developmental, and were uncritical. Dodging dealing with problematics assumptions, such as about the vulnerability of possible participants, was a learnt lesson necessary for researchers to avoid overly laborious impediments and risks of being shut down on topics “too sensitive”. Participating authors felt little agency to challenge institutional assessment regimes of ethical clearance, peer review and curriculum approval, with the effect that deficit framing and the denial of participants’ possible agency was upheld. As discussed in the earlier ‘signs’, most colluded with whitewashing research processes by adopting the norm of obfuscating their authorial positionality and downplaying civil actors’ contributions within published outputs. In such ways, their practices demonstrated the difficulties for academics at the margins to practice “refusals” which “can be an important ‘full stop’ that interrupt exploitative relationships, and that challenge neoliberal and neocolonial conditions of knowledge production” (Hagen et al., 2023, p. 126).

Risk, Social Sanction and Double-Speak

Across the ‘signs’ discussed in the sections above, were indications that threatening the established self-image of NI society in general and of its academia, which came with significant risks.

I know there were other colleagues, either they were raised in NI or they, like me coming from an outsider perspective, trying to problematise this and sooner or later it’s a killer for your career. You might rather then consider either you move to another place or you don’t care about the career. [UI1014]

Risk included adverse impacts to well-being because of social threat or sanction; vicarious trauma experienced through the witnessing of trauma and discrimination experienced by research participants (a concern noted in Williamson et al., 2020); and the powerless to effect change as an academic working on a denigrated topic. Across the three decades, participants had experienced “frustration” due to the inaction of the very ‘stakeholders’ who called for such ‘evidence’.

There is a hesitancy from policy makers in acting on information that could change the lives of minority ethnic communities due to attitudes of many [dominantly-positioned] communities, fear of change or sad to say an element of racism that occasionally raises its head in Northern Irish society and policy. Ideology and theology plays into this as well. Some departments of government are acutely aware of this and tend to shy away from the issues rather than confronting racism at its source [UI1021]

Dissimulation was a response by scholars to avoid “highly charged” [UI1010] melodramatic responses by the majority-placed publics who mattered to party politics. This extended to policy circles where racism was constructed as “a very touchy and sensitive topic… they seem to treat anything related to ethnicity as a hot potato” [UI1009]. ‘Sensitive’ topics were actively discouraged by institutional ethics committees processes; which also had particular responsibilities placed on researchers undertaking local research when it came to disclosure, which differed to the regulations of UK and ROI. An area for further research is whether the legacies of the securitised university (Gearon, 2019) during Home Rule and The Troubles period persist. Participants spoke of “structural reasons that are part of an academic culture… much of this research is really not welcome” [UI1005]. Outsiders felt this even more so, where colleagues “even advised me that maybe you should not write about that, nobody’s going to read it” [UI1017].

There were circumstances where migrant academics, as with the participants of such studies, were exploited in the interests of the dominantly-placed majority. Confirming concerns of identity tax in other contexts (Hirshfield & Joseph, 2012), racialised academics were coopted by institutions, “taking the very few people who are already in that work and diverting them into this other kind of institutional medal getting, then you know you really are undermining the research work” [UI2003]. NI universities only recently exhibited interest in the sectoral Race Equality Charter, “because of Black Lives Matter, the university must be seen to be doing something so that it’s enabling. But I worry I worry about that ‘cause it can go. Anyway, it’s often not self-critical. So what happens when I bring out the critical stuff you know, then how’s that gonna sit?” [UI1001]. Participants expressed concern that superficial interest as performative ‘diversity’ increased the risks of being labelled treasonous, when research raised critiques or problematics of institutional or structural racism and xenophobia.

Prior to the most recent 5 year period, institutional responses were characterised by participants as either benignly or actively unsupportive of academic research on minoritised populations. This was often because of how such enquiry was positioned: “my employers always considered it not as core research but as community outreach” [UI021]. ‘Line managers’ “tolerated” commissioned studies by NI authorities, “as long as it didn’t interfere with the teaching and as long as I could assure them that there would be journal articles and grant money coming from it” [UI2003]. Conflicting institutional logics between ‘public engagement’ and career rewards have been similarly found in other European contexts (Horta et al., 2022).

Research that was perceived to proffer solutions which would reflect well on institutions’ social responsibility imaging, were more positively received. This included ‘evidence’ for ‘impact’ to improve (rather than transform) public services, such as access to healthcare and education through language education, materials et cetera. Deficit discourses about the so-called ‘communities’ studied were consumed and re-produced, even by participating authors who recognised such representation as problematic: “scholars in my field regularly employ that idea of ‘need’ in order to drive the impact justification. And a lot of the impact statements sound a bit white supremacy” [UI2003]. These had use-value for institutional narratives of engagement, responsiveness and the social good, which operated “by shrouding reality, whilst simultaneously appearing virtuous” (Smith, 2021, p. 13). Recognising such double-speak, one participant reflected that intellectuals need to question “are there institutions that are actually sustaining those inequalities even as they claim to be making progress on them? And I would say that higher education is one of those institutions” [UI2003]. These were the indications of value dissonance (Ross-Hellauer et al., 2023) between academics committed to justice and/or affected communities, and exploitative institutions, where the research is “being led by academics who are interested in this work and having to carve out a space for it, which I’m sure the university’s only too glad to afford, particularly in the context of commitment to the social charters and so on, because it looks good” [UI1015]. Universities can, and should, play an active role in resisting the reproduction of deficit thinking (Mampaey & Huisman, 2022) .

Regardless of janiform opportunities, avoidance of change was endemic to public bodies generally, including those funding academic research. Despite calling for “the empirical research to prove what we know anecdotally… research is done, disseminated and then it just sits there and nobody’s using it to do anything” [UI1010]. Participants expressed being incredulous about the reproduction of dysconscious racism and xenophobiaism within such dynamics.

I think that they want to have a superficial engagement with the population but they want them to remain largely invisible. They don’t want to know too much about it. I think first of all because there’re some really difficult truths there that nobody wants to face and they definitely don’t want to address them. I don’t think anyone wants to fix any of these problems. I think they would probably prefer that this research remain as superficial as possible and deal with just very fixable, easy problems because the more complicated realistic things, that lived experience part of it is something that they don’t want to face [UI1020]

Collective consciousness seemed affected by a stunted social imagination, which participants characterised as a fear of social change and allegiance with conservative, rigid social stratifications. The “political landscape of NI mitigates against certain kinds of conversations about race and ethnicity and migration” [UI2003], in part because social change is “in the area that is beyond the horizons of the institutional expectations” [UI1005].

Discourse which posed risk to the marketability of NI academia was not tolerated. The omnipresent sectarianism of the NI social imagination (Vieten & Murphy, 2019) and academic capitalism about NI’s peace-making narratives, both constrained critique and dissent, and misrecognised explorations of social conflicts which intersected or were incommensurate with majority-placed divisions. Dominant discourses of integration, colour-blindness and assimilationist approaches to social stasis had seemingly dulled intellectuals as dissident agents of oppression within society, becoming passive to policymaking discourse of “state formation that hides its incapacity to address rising racism and sectarianism under the fig leaf of ‘good relations’” (McVeigh & Rolston, 2007, p. 1). Dangers identified by participants were structural racism reduced to individual acts of discrimination that had been shown as problematic in theirs, and others, research about NI (Gilligan, 2017; McVeigh, 2015).

… a lot of the attention on this area has been because of that horrible moniker of ‘hate crime capital of Europe’. And I think when that started to disappear a lot of the attention went off us. And the fact that so much of the area has been taken over by the PSNI [police] to the exclusion of wider organisations is a real pity [UI2003].

Authors were not naïve about the task at hand. Most despaired at the avoidance of acknowledging systemic racism. However, less expressed by participants were concerns about coloniality and neoliberalism, which may have impoverished conditions for academic enquiry being more than the debilitating experience of being minoritized in NI. Thus, the conditions of possibility of researching agency, life, joy and pluralistic histories seemed absent from the horizons of participating researchers’ practices and desires. As a participating member of a civil society organisation expressed about such myopia, “It is very difficult to convince the Western world that people from Africa, India, can have knowledge - in this society that prides itself on having taken civilisation to everyone else”.

Insights for the Future Questions

The emphasis on thinking and seeing within the conceptualisation of this paper is informed by intellectuals who emphasize our obligations to call into question the relations of un/critical intellectual frames and attitudes to their roots and routes in the historical foundations of universities’ emergence, their relation to the Enlightenment, and to post/colonial governanceFootnote 7. By analysing signs of dysconsciousness in the ethicality in academic research, the challenges of the praxis of academic responsiveness and responsibility to local publics were exposed. These challenges were compounded in a context where the foundations of the public good, and indeed the ‘publics’, are fractured. A participating author articulated this as a problem, “In the context of Northern Ireland, I came to realise that because of the divided nature of the society, there is no society as such” [UI1005]. Omnipresent sectarianism and coloniality seemingly consumed the dominant collective consciousness, to the detriment of equality and of justice for those othered. Institutional racism is peculiarly morphed due to contextual histories of settler colonialism, racialisation, partition, conflict and fragile peace, refracting Britain’s internal colonialism, and requiring specific considerations which differ to those of universities in England, Scotland and Wales, and that of the Republic of Ireland.

The paper discussed how universities, within a context of social transition, have evaded responsibility to address xenophobia and racism through their research function; and impoverished knowledge production about, and by, those who are positioned as subalterns within that society. White mythologies and whiteliness were found to maintain the status quo, through omission in both public and research data collection, and through social sanction on those who think and do differently in research. By limiting funding mechanisms to technorational, policy-driven and ‘impact’ initiatives, enquiry has been disciplined into misery research (Jansen & Walters, 2020), short-term solutionism, and savour-like philanthropically-patronising discourses, which whitewash the ethical-political responsibility of institutions to address social structures and build anti-racist research cultures. More complex research topics and reflexive methodologies were disabled.

Participating authors’ counter-narratives provided insights about the production of enquiry because of, and sometimes despite, such conditions. Their reflections, from research practices across different time periods over the past thirty years, reveal the schooled conditions for consciousness, critique and the formation of the academic-self and academic-other, particularly as inbreeding and insularity within such institutions continued unaddressed. Those operating against the grain incurred professional and personal cost; most navigated within and around the dominant currents and norms; those able to succeed and profit did so by operating within the slipstream of White Framing. What this paper affirms is the importance of the development of critical race consciousness for academics working between idealised notions of equality and contextual realities of entrenched structural inequality (Zamudio et al., 2009). Whether or not a way through is offered through institutionally-provided ethics training is up for debate. Scholars have argued such training often reneges on critical discussions about populations vulnerable to research misrepresentation and predation, despite the long-demonstrated need and outcries in many contexts (including the USA, Hite et al., 2022), never mind addressing social sanction, injustice and oppression within the institutional murus.

Where collective responsibility is reneged by anchor universities, the burden of knowledge-making may be taken up by outliers; those based in non-local institutions; and non-academic individuals or groups. Indications are that this has been the case within Northern Ireland. Enriching would be research drawing comparisons to non-academic conditions for criticality in knowledge production, and for exploring whether the current pragmatics of open science and community archiving might assist in overcoming barriers to publication for those outside privileged institutional machinations. For ethico-political responsibility to be institutionalised locally, assessment of the processes of institutional change is required, with a focus on addressing the injustices of the janiform, and democratising whose interests research responsiveness serves.

While this article has left unaddressed important questions about what is to be done, it has hopefully identified important areas for further research and deliberation on justice in research production relating to equality. In this study, complaints that higher education internationalisation creates tensions with the local good (Queirós et al., 2023), were complicated by the ‘stranger’ figure of the migrant academic acting counter to the dominant local dysconsciousness racism and xenophobiaism. This contributes insights of authorial agency amid exclusion, to scholarship about coloniality and the positionality of academic migrants (Ezechukwu, 2022). The moral authority of academics and integrity of their research is important, because of the ethical and democratic roles universities play as public institutions. Arendt (1987, p. 45) felt that “only by leaving the community” could such collective responsibility be escaped, arguing that only “refugees and stateless people […] cannot be held politically responsible for anything”. That the social mandate was taken up by academic outliers, including women and migrant academics, contributes complexity to traditional claims about social justice imperatives.

Data availability

The dataset of academic publications is not directly accessible due to copyright restrictions. Open access documentation relating to the outputs are available as Belluigi, D. (2020). Academic research responsiveness to migrants and ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland. Queen’s University Belfast. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10935478. Due to the nature of professional risk for participating authors, the related qualitative dataset has not been published open access.

Change history

22 July 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09552-5

Notes

The term ‘country’ is ideologically disputed, albeit legally accurate for the time period of the publications reviewed in this study, and at the time of writing this paper. NI is both a ‘devolved nation’ of ‘Great Britain and Northern Ireland’, with legislative powers of decision-making at local and centralised levels; and a ‘province’ of the Republic of Ireland (ROI).

Longitudinal census data on ‘race’ is limited. Comparisons between 2001 and 2021 indicate increases in those ‘foreign’-born (from 1.09 to 6.53%); those racialised as other-than-‘white’ (0.8–3.4%); those with religion other-than-Christian (0.4–1.5%) and without religion (2.7–9.3%); and primary languages (other than English, Irish or Ulster-Scots) increased to 4.6% (NISRA, 2022).

Clarity on the visualisation of these tensions, as an embodiment of public authority, came to me during the Advancing Critical University Studies (ACUS Africa) Conference in October 2023 in Accra, when looking at the janiform heads of ancient Koma Land on display at the National Museum of Ghana. The ‘headiness’ extending into the form in Fig. 2 is closer to those terracotta figurines than genres perhaps more recognisable to western audiences, such as ancient Rome’s often disembodied Janus faces (on coins) or ancient Greece’s head-and-shoulder janiform portraits (on cups and vases). My writing on this subject of consciousness and research practice, has been enriched by the questioning of the ‘idea of the African university’.

UK universities’ academic staff composition in 2020 was predominantly ‘white’ (75%); ‘Black, Asian, minority ethnic’ (BAME, the categories used in the UK) 16.5%; missing data at 9%. Of the known recordings, NI had 11% academics of colour (England 19%, Scotland 16%, Wales 13%), with no ‘Black African’ nor ‘Black Caribbean’ professors (Belluigi, 2023). NI-based female academics of colour were at a proportion of 8% of female staff; NI male academics of colour were 16% of the male grouping. Of interest too is the relation to nationality - people of colour comprised 65% of those with non-UK/EU nationalities, compared to 1% of the staff with UK nationality and 1% with EU nationalities.

Exceptions to this are the annually collected public attitude datasets of ARK (established 2000) held by the two research-intensive universities. These longitudinal datasets have included questions about the perceptions of majority-positioned populations to migration, asylum and to some extent ‘race’ (see https://www.ark.ac.uk/ARK/generalhome). While the questions asked are an exception to the rule about large data collection to do with the subject, it should be noted that these questionnaires centre the perceptions of the majority.

In addition to the studies drawn on in the ‘conceptionalising consciousness’ section of this paper, refer to the analysis of social research production with marginalised communities in Canada, undertaken by vander Kloet and Wagner (2023) which raised similar ethical questions about accountability, arguing they were predicated on empiricist and positivist understandings of knowledge. See also South African historian Premesh Lalu’s (2007, 57) article on how ‘Apartheid’s universities’ exposed that “the very blackmail of the Enlightenment: academic freedom is possible as long as one does not question its premises and political conditions”.

References

Allen, K. (2018). Critical Consciousness, Racial Identity, and Appropriated Racial Oppression in Black Emerging Adults [Master of Science, Virginia Commonwealth University]. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5687.

Anderson, B., Narum, A., & Wolf, J. L. (2019). Expanding the understanding of the categories of Dysconscious Racism. The Educational Forum, 83(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2018.1505015.

Anthias, F. (2013). Moving beyond the janus face of integration and diversity discourses: Towards an intersectional framing. The Sociological Review, 61(2), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12001.

Arendt, H. (1987). Collective Responsibility. In S. J. J. W. Bernauer (Ed.), Amor Mundi: Explorations in the Faith and Thought of Hannah Arendt (pp. 43–50). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-3565-5_3.

Aspinall, P. J. (2020). Ethnic/Racial terminology as a form of representation: A critical review of the lexicon of collective and specific terms in Use in Britain. Genealogy, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030087.

Ball, S. J., & Olmedo, A. (2011). Global social capitalism: Using enterprise to solve the problems of the World. Citizenship Social and Economics Education, 10(2–3), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.2304/csee.2011.10.2.83.

Beckles-Raymond, G. (2020). Implicit Bias, (global) white ignorance, and bad faith: The Problem of Whiteness and Anti-black Racism. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 37(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12385.

Bell, D. A. (1980). Brown v. Board of education and the interest-convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93(3), 518–533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1340546.

Belluigi, D. Z. (2023). Research: Inequality in representation and authorship. Paper presented at panel on ‘Diversifying Research.’ Race Equality in Higher Education, Belfast. https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/activities/research-inequality-in-representation-and-authorship-paper-presen.

Belluigi, D. Z., & Moynihan, Y. (2023). Academic research responsiveness to migrants and ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland. A study report. Queens University Belfast. https://youtu.be/jhD5vTtTdqM.

Belluigi, D. Z., Arday, J., & O’Keeffe, J. (2023). Education: The state of the Discipline: An exploration of existing statistical data relating to staff equality in UK higher education. British Educational Research Association. https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/education-the-state-of-the-discipline-an-exploration-of-existing.

Bernstein, S. (2020). The metaphysics of intersectionality. Philosophical Studies, 177(2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01394-x.

Bhambra, G. (2007). Rethinking modernity: Postcolonialism and the sociological imagination. Springer.

Bhopal, K., & Henderson, H. (2021). Competing inequalities: Gender versus race in higher education institutions in the UK. Educational Review, 73(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1642305.

Brady, F. N. (1985). A Janus-Headed model of ethical theory: Looking two ways at Business/Society Issues. The Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 568–576. https://doi.org/10.2307/258137.

Brewer, J. (1990). Sensitivity as a Problem in Field Research: A study of routine policing in Northern Ireland. American Behavioural Scientist, 33(5), 578–593.

Cliffe, J., & Solvason, C. (2022). The messiness of ethics in education. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20(1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09402-8.

Crangle, J. (2018). Left to fend for themselves’: immigration, race relations and the state in twentieth century Northern Ireland. Immigrants & Minorities, 36(1), 20–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619288.2018.1433534.

Crangle, J. (2023). Migrants, Immigration and Diversity in Twentieth-Century Northern Ireland. Palgrave. https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Migrants-Immigration-and-Diversity-in-Twentieth-Century-Northern-Ireland-by-Jack-Crangle/9783031188206.

Crawford, C. E. (2019). The one-in-ten: Quantitative critical race theory and the education of the ‘new (white) oppressed’. Journal of Education Policy, 34(3), 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2018.1531314.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

De Diniz, E. H., & Martinez, J. (2021). The Locus of Enunciation as a way to confront epistemological racism and Decolonize Scholarly Knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 42(2), 355–359. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz061.

Diemer, M. A., Rapa, L. J., Voight, A. M., & McWhirter, E. H. (2016). Critical consciousness: A Developmental Approach to addressing marginalization and oppression. Child Development Perspectives, 10(4), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12193.

Doharty, N., Madriaga, M., & Joseph-Salisbury, R. (2020). The university went to ‘decolonise’ and all they brought back was lousy diversity double-speak! Critical race counter-stories from faculty of colour in ‘decolonial’ times. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1769601.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of black folk. A. C. McClurg.

Ellison, G. (2017). Who needs evidence? radical feminism, the christian right and sex work research in Northern Ireland. In S. Armstrong, J. Blaustein, & A. Henry (Eds.), Reflexivity and Criminal Justice: Intersections of Policy, Practice and Research (pp. 289–314). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54642-5_13.

Equality Commission of Northern Ireland (n.d.). ECNI - Gaps in equality law between GB & NI [Equality Commission of Northern Ireland]. https://www.equalityni.org/Delivering-Equality/Addressing-inequality/Law-reform/Tabs/Gaps-in-equality-law.

Eze, E. C. (Ed.). (1997). Race and the enlightenment: A reader. Blackwell.

Ezechukwu, G. U. (2022). Negotiating positionality amid postcolonial knowledge relations: Insights from nordic-based sub-saharan African academics. Race Ethnicity and Education, 25(1), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1718087.

Feagin, J. R. (2013). The white racial frame: Centuries of racial framing and counter-framing. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-White-Racial-Frame-Centuries-of-Racial-Framing-and-Counter-Framing/Feagin/p/book/9780415635226.

Feenan, D. (2002). Researching paramilitary violence in Northern Ireland. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 5(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570110045972.

Freire, P. V. (1974). Education for Critical Consciousness. Continuum.

Fritz, L., & Binder, C. R. (2018). Participation as Relational Space: A critical approach to analysing participation in sustainability research. Sustainability, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082853. Article 8.

Gearon, L. F. (2019). Securitisation theory and the securitised university: Europe and the nascent colonisation of global intellectual capital. Transformation in Higher Education, 4(0). https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v4i0.70. Article 0.

Gewirtz, S., & Cribb, A. (2020). What works? Academic integrity and the research-policy relationship. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(6), 794–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1755226.

Gillborn, D. (2015). Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in Education. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414557827.

Gilligan, C. (2017). Hate crime. In Northern Ireland and the crisis of anti-racism (pp. 162–196). Manchester University Press. https://www.manchesterhive.com/view/9781526116604/9781526116604.00012.xml.