Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the accuracy of a point-of-view cataract surgery simulation video in representing different subjective experiences of patients undergoing the procedure.

Methods

One hundred consecutive post-cataract-surgery patients were shown a short simulation video of the surgery obtained through a porcine eye model during the first postoperative week. Patients then answered a multiple-choice questionnaire regarding their visual and tactile intraoperative experiences and how those experiences matched the simulation.

Results

Of the patients surveyed (n = 100), 78% (n = 78) recalled visual experiences during surgery, 11% recalled pain (n = 11), and 6.4% (n = 5) recalled frightening experiences. Thirty-six percent of patients (n = 36) were interviewed after their second cataract surgery; there was no statistically significant difference between anxiety scores reported before the first eye surgery and second eye surgery (p = 0.147). Among all patients who recalled visual experiences (n = 78), nearly half (47.4%) reported that the video was the same/similar to their experience. Forty-eight percent of the patients recommended future patients to watch the video before their procedures, and more than a third (36%) agreed that watching the video before surgery would have helped them to relax.

Conclusions

Our model reflects the wide range of subjective patient experiences during and after surgery. The high percentage of patients who found the video accurate in different ways suggests that, with more development, point-of-view cataract simulation videos could prove useful for educational or clinical use. Further research may be done to confirm the simulation’s utility, by screening the video for subjects before operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patients undergoing cataract surgery have reported a wide variety of visual and tactile experiences during their procedures [1,2,3]. Many patients have reported seeing bright lights, colors, and more rarely, surgeon’s hands with surgical instrument visualization [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Other patients have not recalled any visual phenomena altogether [3]. Patients’ experiences have been shown to differ depending on a number of factors including anesthesia route and preoperative counseling [4, 7,8,9,10].

Although the majority of patients do not find their experiences during cataract surgery distressing, it has been reported that between 3% and 19.4% of patients are frightened by visual experiences (8). In addition to intraoperative fear, patients also experience a range of anxiety before undergoing surgery [1, 2, 16]. Fear and anxiety have the potential to cause significant distress to patients, decreasing patient satisfaction. Additionally, in one study severe preoperative anxiety was associated with higher levels of intraoperative pai [1]. Furthermore, fear has the potential to result in a number of suboptimal intraoperative events including hypertension, tachycardia, ischemia, panic attack, and decreased patient cooperation during surgery, possibly leading to increased morbidity and intraoperative complications [17, 18].

Previously, it has been reported that patients who received counseling regarding potential intraoperative visual experiences during cataract surgery report significantly less fear during surgery [9]. Additionally, a number of models for reproducing patient visual perceptions during cataract surgery such as patient generated representations [19], and model eye video clips [20], have been found to be effective preoperative communication tools.

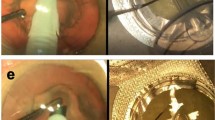

A variety of depictions of patient visual experience during cataract surgery have been indeed created for both clinician and patient education. Illustrations have been created based on patient descriptions [19, 21]; a model eye was suggested to create short video clips of different portions of cataract surgery from the patient’s point of view. [20]

Previously, our group has published a point-of-view simulation of cataract surgery created by using a porcine eye model. [22] The surgeries were video captured from a patient’s perspective (supplement video). This current study aims to examine the range of subjective experiences of patients undergoing cataract surgery and to assess the ability of the aforementioned video clips to represent visual phenomena experienced by patients.

Methods

Informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrollment in the study. Human resource protection program approval was obtained. The described research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A short video simulating the experience of cataract surgery from the patient’s point of view was created by filming a full cataract surgery from a 3 mm maculostomy through the posterior globe of a porcine eye. Full details regarding the methods of creating this video were previously published. (supplementary information) [22]

In this prospective study, 100 consecutive postoperative patients who had undergone cataract surgery were shown the above-described point-of-view cataract surgery simulation video at follow-up appointments within one week of cataract surgery. All eyes included in the study received cataract surgery under topical anesthesia with monitored anesthesia care (MAC) anesthesia at the same academic center. Table 1 demonstrates the type, dosage, and route of sedation received. by patients in our study.

Sedative dose was adjusted by anesthesiologist based on body mass index and comorbidities at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. Surgery was performed by standard phacoemulsification technique with a foldable intraocular lens placement. Excluded were patients younger than 18 years old, or patients with postoperative best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/50 in both eyes, rendering them unable to perceive the video visually.

After watching the simulation video, patients were given a short multiple-choice questionnaire. The survey included questions regarding physical and visual experiences during surgery, as well as evaluation of the eye simulation video. Table 2 includes all questions given to patients in the survey.

Based on the survey results, the proportion of patients who reported various visual and tactile experiences were calculated. Among the patients who recalled a given visual element (For example: lights and flashes, or instrument visualization) during cataract surgery, the proportion of patients who reported that the simulation video was the same or similar to their experience was calculated. Among patients who reported any intraoperative pain, their pain was measured on a numerical rating scale of 1 to 10 [23], with one being low pain and 10 being extreme pain.

Among patients who had undergone delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgeries, preoperative anxiety was measured with a 10-point modified Likert scale (range:1–10, 1 = lowest anxiety, 10 = extreme anxiety) [24]. The average anxiety score was evaluated for both the first and second cataract surgery. Differences between preoperative anxiety scores were determined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The percentage of patients who reported greater, equal, and less anxiety before their first eye surgery compared to their second eye surgery were also calculated.

Respondents were then divided into two groups: those who did recommend the video simulation and those who did not. Proportions of patients who had reported various experiences during cataract surgery were calculated within each subgroup. Two sample Z tests were used to analyze differences between subgroups. Differences were considered significant if the P value was < 0.05. Calculated means and standard deviations were expressed as mean ± SD.

Potential differences between the unilateral patient and bilateral patient subgroups were evaluated using a Chi-squared test, and differences were considered significant if the P value was < 0.05.

Results

There were 100 patients surveyed in this study. Patients surveyed were 55% female and 45% male. In this study, 65% of those patients received only 1% intracameral lidocaine as their topical anesthesia, while 32% received both 1% intracameral lidocaine and 2% topical lidocaine jell. Only 3% of patients received 1% Intracameral lidocaine and 0.5% topical tetracaine during surgery.

Of the patients surveyed (n = 100), 78.8% (n = 78) recalled visual experiences during surgery. Among those who recalled visual experiences (n = 78), 83.3% reported seeing lights/flashes, 23.1% recalled seeing objects/instruments, and 6.4% (n = 5) recalled frightening experiences.

Of the total cohort, 36% (n = 36) were interviewed after their second cataract surgery. Among these patients, there was no significant difference between average anxiety reported before first surgery and the second surgery, with average anxiety changing by − 0.77 (95% CI: 0.38, − 1.93) between the first and second procedure (p = 0.147). More anxiety before the first eye surgery was reported in 48.6% of patients, while higher anxiety before the second eye surgeries was reported by 17.1% of patients, and 34.3% of patients reported the same level of anxiety before both surgeries (Fig. 1). When evaluating the video’s accuracy, there were no statistically significant differences between patients interviewed after their second surgery, and the first. However, 17.2% (n = 11) of unilateral patients reported feeling more anxiety after watching the video versus 5.7% (n = 2) of bilateral patients.

Of the 100 included patients, 11% recalled pain during surgery (n = 11). The average grading of pain (on a scale of 1–10) reported by those who recalled pain (n = 11) was 3.3 ± 1.6. Among those who recalled visual experiences (n = 78), 47.4% reported that the video was the same/similar to their experience. Of those who recalled lights/flashes (n = 65), 46.2% reported that the simulation was the same/similar to that aspect of their surgery. Of those who recalled instrument visualization (n = 18), 72.2% reported that the simulation was the same/similar to that aspect of their surgery. Only 36% of patients agreed that watching the video before surgery would have helped to relax them; however, 48% recommended other patients watch the video before their procedures. Five percent of patients (6.4% of those who recalled visual experiences) recalled frightening visual experiences during surgery.

Discussion

In a previous paper, our group had presented a new tool, a point of view video using a porcine eye, for modeling patient visual experiences during cataract surgery. In this current study, we demonstrate that nearly half of the patients shown this video, found it similar to their experience. The most similar model to ours was published by Inoue et al., who surveyed 20 patients regarding video clips simulating cataract surgery using a model eye. Compared to our results, Inoue et al. reported that video clips were “the same” or “similar” to patient experiences in 50%–70% of patients. [20] An even higher percentage of patients, 80%, recommended the video clips to future patients. [20] However, compared to the 20 eyes included in the paper by Inoue et al., our study has a much larger sample size, with 100 eyes included. Additionally, our study has very significant differences in anesthesia and sedation compared to previous studies evaluating patient visual experiences during cataract surgery [4,5,6, 8, 11,12,13, 15, 17, 25,26,27]. In this respect, our study better represents the accuracy of our video model in representing the typical cataract surgery for patients in the USA; our study demonstrates that even under MAC anesthesia, the vast majority of patients still recall some visual experiences during surgery, and that nearly half of patients would recommend the video to future patients undergoing surgery. Because many patients considered the video to be valuable and recommended the video for future patients, we believe further research should be done to evaluate its potential for clinical use for patients who express anxiety about surgery or wonder out loud about the experience they are about to undergo.

The results of our study have also added to our knowledge regarding patient experiences during cataract surgery in general. In our study, 78% of patients surveyed reported recollection of some visual experience during surgery. This rate of visual recollection is similar to the rate reported in previous studies despite given sedation [4, 5, 5, 6, 11,12,13, 28], and likely represents the visual experiences of routine cataract surgery as commonly performed in the US.

Notably, in our study only 5% of the total patients surveyed (and 6.4% of those who recall any visual experiences) reported experiencing frightening visual experiences. Previous studies have reported that between 3% and 19.4% of patients experience frightening visual sensations during cataract surgeries (1–3,6, 7,9–12). Differences in the rate of fear during cataract surgery have been demonstrated between different routes of anesthesia, as well as with different preoperative counseling [12, 14]. The fact that we found that few patients reported frightening experiences during surgery suggests that sedation via MAC (Monitored anesthesia care) may reduce the incidence of patient fear without substantially altering the probability of patient recollection of visual experience.

Our study shows that only 11% of patients reported pain during this surgery. This is consistent with a previous study describing good pain control in patients undergoing cataract surgery under topical anesthesia and sedation [29], and poor pain control in the absence of sedation (11).

For patients in our study who had undergone consecutive cataract surgeries, a higher percentage of patients reported higher anxiety before the first surgery than before the second surgery. The results, however, were not statistically significant. The results of published literature on this topic have been mixed with some studies demonstrating significant differences [2, 30, 31] and others lacking statistically significant differences [31,32,33] between anxiety levels before first and second eye cataract surgeries. The relatively small sample of patients who had undergone two cataract surgeries in our study (n = 36), may limit our ability to discern subtle differences that may exist in anxiety levels between the two.

There are several limitations of our study. As discussed above, our patients received varying amounts of sedation during their cataract surgery, which could have altered or diminished their perceptions during surgery. Further research assessing this video for patients undergoing cataract surgery under topical anesthesia without sedation may give more reliable results regarding the accuracy of the representations of visual phenomena in our animal model simulation video. Additionally, there is the potential for recall bias, as patients were asked to compare the video to their experience after having undergone the surgery.

In conclusion, our eye model video accurately reflects different aspects of the visual phenomena seen by a large percentage of patients who had undergone cataract surgery. Further studies of patients undergoing surgery under local anesthesia and evaluating the utility of the video footage in patients prior to their surgery could be of importance.

References

Socea SD, Abualhasan H, Magen O et al (2020) Preoperative Anxiety Levels and Pain during Cataract Surgery. Curr Eye Res 45:471–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2019.1666996

Siddiqui Z, Bhatia S, Ahmad Khan S et al (2019) Intraindividual study of anxiety and pain in sequential cataract surgery. Indian J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 5:585–588. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijceo.2019.133

Tan CSH, Eong K-GA, Kumar CM (2005) Visual experiences during cataract surgery: what anaesthesia providers should know. Eur J Anaesthesiol EJA 22:413–419. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021505000700

Newman DK (2000) Visual experience during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia. Br J Ophthalmol 84:13–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.84.1.13

Kah Guan Au, Eong TH, Lim HM, LeeYong VSH (2000) Subjective visual experience during phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation using retrobulbar anesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg 26:842–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0886-3350(99)00452-6

Murdoch IE, Sze P (1994) Visual experience during cataract surgery. Eye 8:666–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1994.164

Eong K-GA, Low C-H, Heng W-J et al (2000) Subjective visual experience during phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation under topical anesthesia 1. Ophthalmology 107:248–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00080-9

Eong KGA, Lee HM, Lim ATH et al (1999) Subjective visual experience during extracapsular cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation under retrobulbar anaesthesia. Eye 13:325–328. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1999.83

Voon L-W, Au Eong K-G, Saw S-M et al (2005) Effect of preoperative counseling on patient fear from the visual experience during phacoemulsification under topical anesthesia: multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Cataract Refract Surg 31:1966–1969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.03.059

Hosoda Y, Kuriyama S, Jingami Y et al (2016) A comparison of patient pain and visual outcome using topical anesthesia versus regional anesthesia during cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ 10:1139–1144. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S109360

Ang C-L, Au Eong KG, Lee SSG et al (2007) Patients’ expectation and experience of visual sensations during phacoemulsification under topical anaesthesia. Eye 21:1162–1167. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702427

Rengaraj V, Radhakrishnan M, Eong K-GA et al (2004) Visual experience during phacoemulsification under topical versus retrobulbar anesthesia: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol 138:782–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.023

Tan CSH (2011) Patients experience different types of visual sensations during cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 95:1758–1759. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2010.201541

Haripriya A, Tan CSH, Venkatesh R et al (2011) Effect of preoperative counseling on fear from visual sensations during phacoemulsification under topical anesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg 37:814–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.11.041

Prasad N, Kumar CM, Patil BB, Dowd TC (2003) Subjective visual experience during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under sub-Tenon’s block. Eye 17:407–409. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700370

Ahmed KJ, Pilling JD, Ahmed K, Buchan J (2019) Effect of a patient-information video on the preoperative anxiety levels of cataract surgery patients. J Cataract Refract Surg 45:475–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.11.011

Tan CSH, Eong K-G, Kumar CM (2005) Visual experiences during cataract surgery: what anesthesia providers should know. Eur J Anesthesiol 22:413–419. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021505000700

Tan CSH, Rengaraj V, Au Eong K-G (2003) Visual experiences of cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 29:1453–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00480-2

Sumich PM, Francis IC, Kappagoda MB, Alexander SL (1998) Artist’s impression of endocapsular phacoemulsification surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 24:1525–1528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0886-3350(98)80178-8

Inoue M, Uchida A, Shinoda K et al (2014) Images created in a model eye during simulated cataract surgery can be the basis for images perceived by patients during cataract surgery. Eye 28:870–879. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2014.80

Verma D (2001) Retained visual sensation during cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 108:1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00424-3

Fukuoka H, Sella R, Fuller SD et al (2019) Video recording and light intensity change analysis during cataract surgery using an animal model. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04288-0

Tomaszek L, Fenikowski D, Maciejewski P et al (2020) Perioperative gabapentin in pediatric thoracic surgery patients—randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 4 trial. Pain Med 21:1562–1571. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz207

Henneman A, Thornby K-A, Rosario N, Latif J (2020) Evaluation of pharmacy resident perceived impact of natural disaster on stress during pharmacy residency training. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 12:147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.11.008

Tranos PG, Wickremasinghe SS, Sinclair N et al (2003) Visual perception during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under topical and regional anaesthesia. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 81:118–122. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00029.x

Wickremasinghe SS, Tranos PG, Sinclair N et al (2003) Visual perception during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under subtenons anaesthesia. Eye 17:501–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700414

Levin ML, O’Connor PS (1989) Visual acuity after retrobulbar anesthesia. Ann Ophthalmol 21:337–339

Chung CF, Lai JSM, Lam DSC (2004) Visual sensation during phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation using topical and regional anesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg 30:444–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0886-3350(03)00612-6

Chen M, Hill GM, Patrianakos TD et al (2015) Oral diazepam versus intravenous midazolam for conscious sedation during cataract surgery performed using topical anesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg 41:415–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.06.027

Ursea R, Feng MT, Zhou M et al (2011) Pain perception in sequential cataract surgery: comparison of first and second procedures. J Cataract Refract Surg 37:1009–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.01.020

Jiang L, Zhang K, He W et al (2015) Perceived pain during cataract surgery with topical anesthesia: a comparison between first-eye and second-eye surgery. J Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/383456

Bardocci A (2012) Second-eye pain in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 38:1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.07.018

Sharma NS, Ooi J-L, Figueira EC et al (2008) Patient perceptions of second eye clear corneal cataract surgery using assisted topical anaesthesia. Eye Lond Engl 22:547–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702711

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS, SDF, SSB, HF, and NAA contributed to the study conception and design. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation were performed by RS, RRL, AAA, SSB, and NAA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RS, RRL, and NAA. All authors participated in critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose

Ethical approval

Human resource protection program approval was obtained. The described research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrollment in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file 1 (MP4 52531 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sella, R., Lian, R.R., Abbas, A.A. et al. Evaluating the accuracy of a cataract surgery simulation video in depicting patient experiences under conscious anesthesia. Int Ophthalmol 43, 4897–4904 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-023-02892-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-023-02892-y