Abstract

In this paper we defend the idea that dyadic gratitude — i.e. gratitude in absence of a benefactor — is a coherent concept. Some authors claim that ‘gratitude’ is by definition a triadic concept involving a beneficiary who is grateful for a benefit to a benefactor. These authors state that people who use the term gratitude in absence of a benefactor do so inappropriately, e.g. by using it as an interchangeable term for ‘appreciation’ or ‘being glad’. We believe that the conceptual analyses which underlie such statements are too strongly focused on language and pay insufficient attention to the lived experience of gratitude. Thus, we have conducted a phenomenological analysis of several experiences in which people report feeling gratitude in absence of a benefactor. Informed by our phenomenological findings, we argue that dyadic gratitude is a coherent concept that shares certain core experiential elements with triadic gratitude. Gratitude is an appreciative response that construes its object as a gratuitous good and as a (metaphorical) gift; it is characterised by a receptive-appreciative attitude, an awareness that we are in some sense dependent on something other than ourselves, and a motivational impetus to promote, celebrate and/or radiate goodness. Finally, we argue that dyadic gratitude is a useful concept because it enables us to think and communicate effectively about a set of experiences. Moreover, it is also a scientifically and philosophically relevant concept, since it seems to be associated with various positive psychosocial effects and might even be developed as a virtuous disposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For a long time, philosophers, psychologists and educational theorists paid little attention to the phenomenon of gratitude, but in recent decades this has changed drastically and gratitude has grown into a large, multidisciplinary field of research (Gulliford et al. 2013). Once again, since Cicero coined gratitude ‘the mother of all virtues’, philosophers investigate gratitude and many of them proclaim its status as a (moral) virtue. Furthermore, some psychologists consider “gratitude as ‘social glue’ that fortifies relationships (…) and serves as the backbone of human society” (Allen 2018, p. 2). Moreover, many studies (mostly from the field of positive psychology) have demonstrated that gratitude, induced by various types of interventions in clinical and school settings, is related to a wide range of positive psychosocial effects — think of improved subjective well-being (Wood et al. 2010; Dickens 2017; Jans-Beken 2020), school achievement (Froh et al. 2011), prosocial behavior (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006) and better interpersonal relationships (Algoe 2012; Bartlett et al. 2012), among others. Popular self-help books and blogs have embraced such findings and also proclaim the importance of gratitude.

But what exactly is gratitude? Despite, or perhaps as a consequence of the fast-paced increase of research into gratitude, the academic literature still suffers from a lack of conceptual clarity (Gulliford et al. 2013). Gratitude is understood as either a positive (pleasant) or mixed emotion, respectively opposed to or including negative (unpleasant) feelings such as indebtedness, shame and guilt. Moreover, one of the most notable disagreements concerning this concept regards the question whether gratitude in the absence of a benefactor is a meaningful concept.Footnote 1

The experience of receiving a gift from someone is probably the most common association with the concept of gratitude. In such experiences, gratitude has a triadic structure, consisting of a beneficiary who is grateful to his/her benefactor for a received benefit (the gift). Yet people also frequently report feeling grateful in absence of a benefactor, e.g. gratitude for the birth of a healthy child, the time allowed to spend with loved ones, or for seeing a beautiful starry sky — this also happens to secular people, who do not believe these things are given to them by (a) God. In such experiences, gratitude has a dyadic structure, consisting of a beneficiary who is grateful for a benefit — but not to anyone. While benefit appraisals (a beneficiary appreciating a benefit) play a central role in both conceptualizations, only the former requires ‘perceived agency’, that is, believing that the gift is given by an intentional agent (Rusk et al. 2016). Consequently, in triadic gratitude it is obvious to whom the gratitude should be directed, whereas this is not so obvious in dyadic gratitude.Footnote 2

Authors strongly disagree about the way in which we should understand the distinction between triadic and dyadic conceptualizations of gratitude. Steindl-Rast (2004) describes them as “phenomenologically different modes of experience” (p. 282), while McAleer (2012) argues that “there are not two kinds of gratitude here but one, sometimes aimed at targets, sometimes not” (p. 57). More strikingly, however, some authors discard the dyadic conceptualization and state that gratitude is by definition a triadic concept. They argue that laypeople who use the term ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor by definition do so inappropriately, using it as an interchangeable term for ‘appreciation’ or ‘being glad’ (Fagley 2018; Hunt 2022; Manela 2016; Roberts 2004). Besides, Fagley asserts that dyadic gratitude is a vague concept which is not fine-grained enough for scientific research. Indeed, many authors (mostly philosophers) subscribe to such criticisms and adhere to the narrower triadic conceptualization of gratitude (Carr 2013; 2015; Manela 2016; 2018; Tudge et al. 2015).Footnote 3

But is it true that gratitude conceptually requires a benefactor and that dyadic gratitude is merely a form of appreciation? Everyday language suggests that the triadic concept does not provide an exhaustive description of the range of gratitude experiences, and draws our attention to the possibility of dyadic gratitude experiences. But can we in fact identify experiential characteristics which justify using the term ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor? If so, how do dyadic and triadic concepts of gratitude relate to each other? The aim of this paper is to answer such questions by investigating experiences and concepts of gratitude.

This paper proceeds as follows. In section 2, we will take a closer look at the manner in which gratitude is typically delineated in philosophical papers, namely as a triadic concept. We will also consider criticisms of dyadic gratitude and argue that the conceptual/linguistic analyses that underlie these pay insufficient attention to the lived, pre-reflective experienceFootnote 4 of gratitude. Thus, in section 3 we will conduct a phenomenological analysis, aiming to apprehend the lived experience of dyadic gratitude and to capture its essential experiential elements. In section 4, we will return to the linguistic dimension and conduct our own conceptual analysis of gratitude; informed by our phenomenological findings, we will take under scrutiny whether ‘gratitude’ is an appropriate term in absence of a benefactor. We will also investigate how triadic and dyadic concepts of gratitude relate to each other, and whether both are useful concepts.

2 Paradigmatic Gratitude and Criticisms of Dyadic Gratitude

One of the most rigorous and paradigmatic accounts of gratitude is provided by Roberts (2004). In his often cited paper, Roberts conducts a conceptual analysis of gratitude which results in a very specific triadic conceptualization. He explains that emotions are ‘concern-based construals’, which involve evaluative and motivating interpretations or perceptions of reality through the lens of certain concerns. Roberts argues that gratitude is such a concern-based construal with the following terms:

‘I am grateful to S for X’ can be analyzed as follows:

- 1.

X is a benefit to me (I care about having X).

- 2.

S has acted well in conferring X on me (I care about receiving X from S).

- 3.

In conferring X, S has gone beyond what S owes me, properly putting me in S’s debt (I am willing to be in S’s debt).

- 4.

In conferring X, S has acted benevolently toward me (I care about S’s benevolence to me, as expressed in S’s conferral of X).

- 5.

S’s benevolence and conferral of X show that S is good (I am drawn to S). (Or: S’s goodness shows that X is good and that, in conferring X, S is benevolent.)

- 6.

I want to express my indebtedness and attachment to S in some token return benefit. (p. 64)

Roberts stresses that the ‘I’ above interprets a situation and may be mistaken in doing so — e.g. X does not have to be an actual benefit to make us grateful, but we should construe it as a benefit, we should have the impression that X is a benefit (which has been bestowed upon us benevolently etc.).

Let us consider an example of gratitude which meets Roberts’ criteria. Imagine you come to doubt your paper’s structure in the prospect of an impending deadline, when your colleague Sophia walks in and, noticing you are worried, somewhat absently gazing at your screen, asks if everything is all right. After listening to your problem, she offers to proof-read your paper before the end of the week. As Sophia listens to you attentively, although very busy herself and not obliged to help, you realize that she does not want anything in return for this favor, but genuinely seems to care about you. Besides appreciating the feedback she offers you — which, given her experience and considerate attitude, you presume to be very useful — you are most of all struck by her pure benevolence; this experience triggers a feeling of gratitude, which you dearly want to express to her — first, by smiling and saying ‘thanks’, and perhaps later by returning a favor.

This illustration of Roberts’ criteria is undeniably a paradigmatic example of gratitude, but is it also the only type of experience which we can appropriately denote with the term ‘gratitude’? Roberts (2004) answers this question affirmatively, pointing out that his “analysis of gratitude as a three-term construalFootnote 5 has stressed the benefactor term: To be grateful is to be grateful to someone” — adding that “the benefactor must be construed as a responsible agent” (p. 63). Roberts is aware that people use the word ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor, but argues that such utterances are inappropriate: “an atheist might say, ‘I’m so grateful that it didn’t rain on our picnic.’ Here, grateful just seems to mean glad, and (…) people who use the word gratitude for this emotion (…) are speaking loosely and even misleadingly” (p. 63).Footnote 6 Roberts indicates that people might feel genuine gratitude in such experiences when they attribute benefits (e.g. the sunny weather during our picnic) to the benevolent intentions of nonpersonal causes such as fate or evolution — i.e. when they personify these causes and construe them as agents that are ‘wishing them well’. He remarks that if people: “know that fate or evolution is not in fact wishing them well and intending their benefit, their emotion will be irrational, in a mild and harmless sort of way” (p. 63). This means that Roberts does not allow for the possibility of genuinely dyadic gratitude; for him, gratitude is always a three-term construal, but this construal may be either appropriate or inappropriate, rational or irrational, depending on the situation.

Roberts (2004) offers a plausible conceptualization of gratitude which seems like a suitable starting point for scientific research into this concept. Yet, his critique of dyadic concepts of gratitude is less convincing. The fact that Roberts deliberately deviates from ordinary language is not problematic per se, because scientific research does sometimes require more fine grained concepts than laypeople use, and philosophical analysis can suggest improvements of ordinary language. Indeed, it does seem reasonable that people who say they are ‘grateful for the good weather during their picnic’ often speak loosely, and in fact mean that they feel glad or lucky about the good weather. Yet, the terms glad or lucky do, at least sometimes, seem to fall short when used to describe the emotions that (secular) people feel on occasion of the birth of a healthy child, in connection with the time allowed to spend with loved ones, or when seeing a beautiful starry sky. There seems to be something more to such experiences than merely feeling glad or lucky; but what experiential elements might characterize such experiences, and, more importantly, do these elements justify using the term ‘gratitude’ to denote such experiences?

At this point, it is helpful to take a step back and consider the methods employed by philosophers concerned with the conceptual clarification of gratitude; like Roberts (2004), most of them favor an analytic approach and conduct conceptual analyses (see Carr 2013; Hunt 2022; Manela 2016; Rush 2020). Gulliford and colleagues (2013) argue that in such analyses, many philosophers tend to superimpose “their preferred assumptions on gratitude in the name of conceptual rigor – thus airbrushing purported deviant or misplaced uses” (p. 287), thereby discarding different concepts of gratitude which might have their ‘own particular function’. Gulliford and colleagues rightly point out that such philosophers should pay closer attention to lay understandings of gratitude. In addition, however, it should also be noted that conceptual analyses have a strong linguistic focus and, consequently, very little attention has been paid to the lived, pre-reflective experience of gratitude.Footnote 7 Language is part of and shapes our experience, and it can be an important source of information regarding our experiences, but people experience many more things than they verbalize. Especially with regard to a complex subjective experience like gratitude, our understanding might benefit from an analysis of its lived experience. For this, we conduct a phenomenological analysis of gratitude.

3 The Lived Experience of Dyadic Gratitude

In this section we conduct a phenomenological analysis by considering several experiences in which people occasionally report feeling gratitude in absence of a benefactor. Subsequently, we will analyse and compare the constitutive experiential elements of these experiences. But before we embark on our phenomenological analysis, let us clarify what we mean by such analysis.

3.1 Phenomenological Analysis

We use the term ‘phenomenological analysis’ to indicate the investigation of lived, pre-reflective experiences.Footnote 8 Such experiences consist of a complex array of experiential elements of which we are only partially and usually minimally consciously aware. By articulating and thematizing the most defining experiential elements implicit in such lived experiences, and by identifying the components shared across several such experiences, we hope to further our understanding regarding ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor.

In qualitative inquiry it is sometimes assumed that people can simply access, capture and adequately describe their lived experiences through introspection. However, pre-reflective experience is not simply available to us as an object of introspective reflection, because the very act of reflecting not only temporally lags behind, but also objectifies and thereby interrupts the pre-reflective experience it intends as its object (see Van Manen 2016, pp. 34; 58–60; Zahavi 2015, p. 186). Besides, in reflection our various taken-for-granted presuppositions interfere with and influence how we perceive our primal, currently reflected on lived experience. This means that we cannot reflectively capture the ‘now’ of lived experience and can never know its full significance. This might seem to render our phenomenological pursuit impossible. However, the aim of phenomenological reflection is not to reproduce lived-experience — which would render such reflection superfluous — but to contribute to a reflective awareness of lived experience by accentuating its most characteristic components and structures.Footnote 9 Such phenomenological reflection requires us to become aware of usually taken-for-granted aspects of lived experience; in other words, it requires us to adopt or cultivate a phenomenological reflective method or attitude.

So how do we take up a phenomenological reflective attitude? Van Manen (2016, pp. 218–228) describes four strategies that help to elicit such an attitude and, more specifically, to remove that which obstructs optimal access to our lived, pre-reflective experience.Footnote 10 First, in order to disrupt our usual attitude of taken-for-grantedness, it is important to evoke a sense of wonder about the phenomenon we are interested in; this sense of wonder should be nourished during the phenomenological inquiry.Footnote 11 Second, we should maintain a certain openness to the phenomenon of interest by bracketing as many assumptions as possible that might lead us to premature understandings of this phenomenon. Third, it is important to foster a sensitivity to the concrete reality of lived experience by bracketing the abstract, theoretical conceptions that might hinder access to the concreteness of our lived experience. Fourth, we should seek the most appropriately fitting approach to investigate and express our findings regarding the phenomenon of interest by bracketing all conventional methodological techniques and by reflecting on our own reflectivity.

Once we have opened up to our lived experience, we return to our phenomenon of interest with a reflective phenomenological attitude of wondering openness, aiming to uncover and express its unique constellation of experiential elements. In this article, we intend to do so by describing several personal experiences of gratitude in absence of a benefactor. We will also engage in an iterative process of reflecting on our experiential descriptions — do they match the original lived experiences? — and finetuning them by adding nuances, cutting back irrelevant details and by emphasizing seemingly important meanings embedded in the experiences. During this process it is important to establish and maintain an emotionally charged connection with a vivid image of the lived experience that we aim to describe; when this connection is lost, it should be re-established before we continue describing the experience (see Petitmengin 2006). In this manner we shape our experiential descriptions into anecdotes (see Van Manen 2016, pp. 251–256). The purpose of these anecdotes is not to express what we know regarding the phenomenon of interest, “but, in an evocative manner, an ‘anecdotal example’ lets one experience what one does not know (in an intellectual or cognitive sense)" (p. 256). Thus, in our experiential descriptions (see section 3.2) we try to employ rich, evocative language (as opposed to more analytical language) in order to create vivid images that appeal to the imagination. Such language does not only enable the reader to empathize with the examples, but in fact aids the reflective process since it evokes and helps the reflective agent to uncover the experiential elements implicit in lived experience.

Finally, we will identify which experiential elements seem to emerge from our anecdotal examples and analyze relevant differences and similarities between the examples (see section 3.3).Footnote 12 Here we aim to pin down the constellation of experiential elements that constitutes the essence of gratitude experiences in absence of a benefactor. Van Manen (1997/2016) stresses that “the word ‘essence’ should not be mystified” (p. 39), but can instead be understood as a linguistic construction, a description that reveals the unique structure of a lived experience and that allows us to grasp its meaning. Indeed, the very aim of our phenomenological analysis “is to transform lived experience into a textual expression of its essence — in such a way that the effect of the text is at once a reflexive re-living and a reflective appropriation of something meaningful” (Van Manen 1997/2016, p. 36). In contrast to the evocative language in our experiential descriptions (see section 3.2) — which is particularly helpful to evoke a reflexive re-living — in section 3.3 we use more analytical language to pin down and describe patterns of experiential elements that seem to emerge. As such, section 3.3 should also provide us with useful working material for our subsequent conceptual analysis.

3.2 Examples of Dyadic Gratitude Experiences

For our first example, imagine yourself walking home from work on a cold winter’s day. You feel tired, fed up with leaving and returning home in the dark, and then it also starts raining. You feel sorry for yourself and a subtle feeling of bitterness begins to take hold of you, but then you encounter a homeless woman sitting in the rain, not even bothering to find shelter. Struck by this image you walk on, feeling somewhat ashamed about your self-pity. Attempting to empathize with this woman, you try to imagine what hardships she must endure living on the streets. As you wonder why she ended up homeless, you start to visualize different possible explanations and shift your focus to the countless humans around the world who fell prey to these misfortunes — you think about refugees of war and victims of childhood trauma with an aftermath of drug-abuse. Suddenly you realize, not just intellectually but in an emotionally charged sense, how arbitrarily and unequally goods and opportunities in life are distributed, and how lucky you have been with the cards you have been dealt. You become aware how precious it is to have a roof over your head and feel grateful for having such a place. As you realize that your ‘house’ — this safe place where you are sheltered against the cold and can enjoy dinner with your family — also supports the deeper meaning of having a place to call home, the feeling of gratitude deepens. This feeling is accompanied by the wish that all people may one day find such a place. Furthermore, you feel motivated to help homeless people — you cannot buy them a house, but you could at least offer a warm meal or drink; more generally, you feel motivated to refrain from unwarranted feelings of self-pity and to cherish your good fortune.

For a different type of experience, imagine yourself lying in the chair of a planetarium.Footnote 13 The lights go out and the seats of the planetarium appear projected onto a dome above you. Suddenly the projection starts zooming out with a rapidly accelerating speed, the roaring sounds combined with a shaking chair give you the impression that you are actually ascending, consecutively leaving behind the planetarium, our city, country, planet earth, solar system, the Milky Way and the Local Group all the way to the frontier of the observable universe. When the zooming out finally stops, you are left awestruck, amazed by the infinite size of the universe and consequently feeling very small. As a narrator informs you about the Big Bang and history of the universe, you cannot help but wonder why this mysterious event has taken place and why anything exists at all. But then we start zooming in again until we reach our solar system. The narrator points out that almost all space in the universe is empty and explains why life is only possible under very specific conditions — a relatively minor change in the distance between our planet and the sun would render earth lifeless. Again we start zooming in, until we finally see planet earth in more detail; as you gaze at it, a warmth spreads through your stomach and you feel your chest expanding. Contemplating this wondrous ‘pale blue dot’, which sustains all life you know, against the backdrop of vast empty space, you feel a strong connection with and gratitude for planet earth. This feeling is accompanied by an awareness of the fragility of our planet — what would happen if a hole was punctured in the tiny atmospheric layer surrounding it? — and a corresponding motivation to take better care of it.

As you leave the planetarium, you contemplate the interconnections between the sun, the trees and the people around you, and feel a strong sense of connection with the world; you realize that you are also a part of this bigger interconnected whole. Once again you ponder why anything exists at all, and merely considering the possibility of an ‘absolute nothingness’ — however abstract and unimaginable such a thought is — makes you see the world in a new light. A strong sense of wonder takes hold of you and everything appears to you as strange, ungraspable and mysterious. Suddenly a new of wave of sensations rushes through you, a warmth in your belly, an expansion of your chest, a feeling of joy that draws a smile on your face and makes you feel lighter, an awareness of your body which, paradoxically enough, seems to widen and expand beyond your ordinary bodily boundaries; ‘what a beautiful and wondrous gift this life is’, you say to yourself. You feel immersed in a profound sense of gratitude, and wherever your mind’s eye turns you see beautiful gifts emerging: grateful for the warmth of the sun; grateful for your body and its abilities to see, hear, taste, feel and/or smell the world; most of all you feel grateful for the time allowed to spend with your loved ones. This feeling is accompanied by a vague but powerful motivation to ‘celebrate and make the best out of life’, to enjoy, share and promote the good in life by engaging in meaningful relationships and by ‘radiating’ your gratitude.

3.3 Constitutive Experiential Elements of Dyadic Gratitude

So what experiential elements constitute these different experiences of dyadic gratitude? Perhaps most obviously, all these experiences are characterized by a sense of appreciation. However, this sense of appreciation does not merely construe its object as a ‘benefit’, but involves an acknowledgement of the contingent, uncontrolled and undeserved nature of this good. Here, ‘undeserved’ does not imply that it is unwarranted that you receive the good, but it points out that we are not entitled to or have merited this good.Footnote 14 In our examples of dyadic gratitude experiences we realize that we mysteriously happened to come into being, on this particular planet where life as we know it is possible, and, opposed to so many others, have been blessed with (opportunities to find) a home — these goods might just as well not have been and it seems presumptuous to see them purely as an achievement of our own. Thus, whereas appreciation construes something as good, dyadic gratitude construes its object as a gratuitous good, thereby inspiring an impression of the good as a metaphorical gift.

Connected to the sense of gratuitousness of the good, all our examples of dyadic gratitude involve a realization — again, not just intellectually but in an emotionally charged sense — that the good in our lives (our home, life-conditions on planet earth and the bare fact of our existence) results from forces which are beyond the scope of our complete control. As we become aware how our life is interconnected with, shaped by and revolves around countless uncontrolled goods, we recognize our dependencyFootnote 15 in relation to such goods. Our examples indicate that this insight often triggers an alteration of our sense of self. Recognizing our dependence, we still experience our ‘self’ as a somewhat discrete, individual locus of control, but there is a noticeable shift from a feeling of separation towards connectedness. In the first example, this change is quite subtle; here, our empathy and the recognition that we, just like our fellow human beings, are shaped by uncontrolled forces make us feel less separated from others. In the second and third example there is a more profound modification of boundaries, as we experience ourself as an interdependent part of a larger whole — i.e. (the social community living on) planet earth and the grand ‘cosmic play’ of existence.

Our examples also indicate that dyadic gratitude is characterized by a receptive-appreciative attitude. This receptive mode of attention is characterized by an openness to the world around us, and opposed to the way most of us (at least in modern western societies) usually attend to the world, namely with a focused and goal-oriented attitude — perceiving the world selectively through the lens of our goals, blinded to that which is irrelevant with regard to our goals. Thus, although dyadic gratitude is a response to a particular good, often it can relatively easily shift its focus because of the corresponding receptive attitude — a receptivity to (what appear as) gifts. This is best visible in the last example, where gifts appear ‘wherever your mind’s eye turns’. Similarly, in the first experience the value of ‘having a roof over our head’ seems to be the primary object of gratitude, but this focus shifts to the broader value of having a place to call home. Besides, there also is a general recognition of ‘the good cards we have been dealt’. Thus, it is not hard to imagine that this gratitude might easily shift its focus to your parents’ upbringing, the life-conditions that characterize the time and place you were born in or the numerous people throughout history whose work created our present societies’ welfare. Likewise, in the second example our gratitude can shift its focus from planet earth as a whole to the particular manifestations of life on this planet.

The receptiveness associated with dyadic gratitude does not imply that it is a passive state of mind; on the contrary, the three examples illustrate that dyadic gratitude entails an evaluative tendency in which our imagination plays an important role. By considering a good against the background of either something worse or its possible absence, our imagination helps us to reveal its value — value we are often blind to because we take the good for granted. This play of our imagination can but does not have to precede feeling gratitude; e.g. in the second example, our ‘galactic journey’ has made us receptive to the value of and grateful for planet earth, and this experience instigates an imaginative play concerned with the planet’s fragility and the manner in which we can take care of it.

This last point indicates a final experiential element which all three experiences have in common, namely that they entail a strong motivational impetus to promote and enlarge, and/or to celebrate and radiate goodness.Footnote 16 The first example is most directly directed towards helping people, but in the other two examples there is also an implicit concern for living beings; concerned with the health of the planet, we also consider (some of) the beings living on it, and even the ‘gratitude for existence’ entails a motivation to foster meaningful relationships with and to care for others.Footnote 17 However, it should be noted that the motivational impetus associated with dyadic gratitude does not necessarily involve a concern for other living beings. Again, our imagination seems to play an important role here by shaping images or ideals which help to direct our motivational impetus; e.g. in our first example, gratitude can trigger imagining ourselves doing charity work helping homeless people, but we can also imagine ourselves (merely) refraining from self-pity and cherishing our good fortune.

4 The Concept of Dyadic Gratitude

Let us now return to the questions of a conceptual nature. We will consecutively analyse whether or not dyadic gratitude can appropriately be understood as (a form of) gratitude, how it relates to triadic gratitude, and explore whether dyadic gratitude seems like a useful concept.

4.1 Phenomenological-Conceptual Vindication of ‘Gratitude’ in Absence of a Benefactor

To begin with, let us again consider the aforementioned critique of dyadic gratitude. According to Roberts (2004), atheists who use the term ‘gratitude’ without ascribing the origins of their feeling to a benefactor (e.g. in relation to the experiences we described in section 3.1) are ‘speaking loosely and even misleadingly’, because in fact they merely feel glad. Lacewing (2016) criticizes this line of reasoning and offers three arguments why Roberts’ analysis is not linguistically correct. “First, such phrases do not change their meaning depending on whether they are uttered by theists or atheists (as Roberts supposes)” (p. 149). Secondly, Lacewing argues that using the term ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor is ‘rooted in etymology’; gratitude its Latin root gratus means both ‘pleasing’ and ‘thankful’, which “does not specify the response as necessarily to a giver, rather than just to an undeserved good” (p. 149). This shows that the idea of dyadic gratitude is not a conceptual innovation, let alone eccentricity, but a possibility inherent in the origins of the concept. So, Lacewing argues, psychology — the fact that people actually experience dyadic gratitude — reflects the etymology of the concept. Thirdly, the suggestion that people merely feel ‘glad’ in such experiences “fails to specify the response precisely enough – it misses out how the response picks out the undeserved and uncontrolled nature of the good” (p. 149). According to Lacewing, what unites different types of gratitude (more on this in the next section) “and distinguishes gratitude from other emotions, is the focus on the undeserved, gratuitous, contingent nature of the good” (p. 150).

This last point connects to and can be elaborated upon by our phenomenological findings. Indeed, in contrast to other positive emotions dyadic gratitude involves a strong focus on the contingent, uncontrolled and undeserved nature of the good. Whereas feeling glad can be an appreciative response to any good and does not even have to be focused on a particular object, dyadic gratitude is an object-centered appreciative response that construes its object as a gratuitous good. Therefore, an impression of the good as a metaphorical gift lies at the heart of dyadic gratitude experiences. Connected to this sense of gratuitousness, dyadic gratitude is characterized by an (often inarticulate) awareness of our relatedness to something other than ourselves — the aforementioned ‘forces which are beyond the scope of our complete control’ — and this awareness is specifically marked by a willingness to recognize our dependency on this other.Footnote 18 Besides, dyadic gratitude involves a receptive-appreciative attitude. Van Tongeren (2016) argues that a receptive attitude is conditional for and might in fact be one of the most characteristic elements of gratitude, because it enables us to receive a good as a gift, instead of seeing it as an accomplishment of our own. This explains why we cannot seem to force ourselves to be grateful, but can only evoke this state of mind by remaining receptive.Footnote 19 Finally, as dyadic gratitude construes its object as a gratuitous good that should not be taken for granted, this perception includes an impetus to promote and enlarge, and/or to celebrate and radiate goodness. Although dyadic gratitude is often accompanied by or ignites a motivation to take somewhat specific action or make some general changes in the way we live our lives (see examples in section 3.2), this is not always the case; sometimes such a specific motivation is lacking and the impetus to ‘celebrate and radiate goodness’ coincides with and is fulfilled by the very feeling of dyadic gratitude.

In our phenomenological analysis, we identified other experiential elements which often accompany dyadic gratitude experiences, but these do not seem necessary prerequisites for this concept. Although dyadic gratitude always entails a certain acknowledgement of our dependency, this might be a very subtle awareness residing in the background of our experience. Consequently, dyadic gratitude does not always entail an alteration of our sense of self. Likewise, the evaluative tendency in dyadic gratitude does not necessarily involve a play of our imagination; sometimes the gratuitous goodness of a (metaphorical) gift appears unchallengeable to us and a joyous feeling of gratitude occupies our entire mind, leaving no space for further reflective considerations.

Building on our conceptual delineation of dyadic gratitude thus far, let us now consider two related and/or borderline casesFootnote 20 regarding the concept of gratitude. For both examples, imagine yourself leaving home for work, walking back because you forgot your phone, and then leaving home again. For the first example, imagine that a €100 bill is blown right in front of you when you step outside of your house the second time. For the second example, instead imagine you notice a thick branch falling on the sidewalk about 50 meters in front of you, more or less at the location where you would have currently been walking in case you had not forgotten your phone. In both examples, imagine yourself experiencing a pleasant emotion and being fully aware of the contingency of your ‘fortunate timing’. What is the proper term for this feeling, are we feeling fortunate, grateful or perhaps both? In fact, we cannot answer this question based on such general descriptions; instead, we need a detailed profile of experiential characteristics to determine the most appropriate term for our feelings.

Like gratitude, feeling fortunate or lucky does involve an appreciation of a contingent, gratuitous good. Yet, when we feel fortunate the utility of the good is more salient than the manner in which it relates to us — thus it is not characterized by an awareness of our dependency. Besides, feeling fortunate might be accompanied by the impression that we can somehow take advantage of a situation, which indicates that feeling fortunate does not necessarily imply a receptive attitude towards its object. In contrast, dyadic gratitude involves the impression of receiving a metaphorical gift and a corresponding (often inarticulate) awareness of the uncontrollable manner in which this gift shapes our life. In a sense, feeling fortunate is more superficial and gratitude more profound. This distinction seems to implicate that our first example, in which we profit from finding a €100 bill, is more likely to make us feel fortunate, whereas the second example, in which we escape serious harm or even death, is more likely to make us feel grateful. However, we again want to stress that the precise profile of experiential characteristics determines which term is most appropriate to describe our feeling; finding a €100 bill might also make us feel grateful, especially when it enables us to do something that is important to us — e.g. buying an expensive medicine for our dying cat, which we could not otherwise afford.

To complicate this distinction further, we also want to stress that ‘feeling fortunate’ and ‘gratitude’ are not mutually exclusive concepts; there is no hard line separating them. Sometimes both terms seem appropriate to describe our experience, or feeling fortunate might develop into a feeling of gratitude. This demonstrates that there are certain ‘grey areas’ in which it is hard to determine what term or concept best describes our experience. This point also applies to the distinction between gratitude and other neighbouring experiences, such as feeling glad.

To summarize, dyadic gratitude is an appreciative response that construes its object as a gratuitous good and as a (metaphorical) gift; it is characterised by a receptive-appreciative attitude, an awareness that we are in some sense dependent on something other than ourselves, and a motivational impetus to promote, celebrate and/or radiate goodness. This constellation of experiential elements is characteristic of all experiences commonly expressed in terms of gratitude, and appears to be sufficient for using the term ‘gratitude’. Thus, pace Roberts, the use of ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor in ordinary language, rather than being irrational, is supported by a more precise analysis of phenomenological differences between dyadic gratitude and experiences such as ‘merely’ feeling glad or fortunate, and crucial similarities with triadic gratitude (we will elaborate on these similarities in the following section). Thus, in our view dyadic gratitude is a coherent concept, true to and based in lived experiences of gratitude in absence of a benefactor.Footnote 21

4.2 The Relation Between Triadic and Dyadic Gratitude

The next question is how dyadic and triadic concepts of gratitude relate to each other. To investigate, let us consider what experiential elements associated with dyadic gratitude also apply to the aforementioned paradigmatic example of triadic gratitude (see section 2). As you realize that Sophia has gone beyond what she owes you and genuinely seems to care about you, you do not just appreciate but are ‘struck by her pure benevolence’; this sense of astonishment or pleasant surprise indicates that the contingent and undeserved nature of her benevolence is particularly salient. Besides, astonishment or surprise implies a receptive attitude, an open receptiveness that is clearly opposed to a focused, goal-oriented mode of attention (Frijda 1986). Furthermore, the very recognition of another’s benevolence seems to indicate an awareness that we are dependent on the goodwill of others. This does not imply that we are helpless without the other, but that we are affected by and do not have control over his/her voluntary bestowal of goodwill. Finally, in the example of Sophia’s benevolence there is clearly a motivational impetus to radiate (our appreciation of) and promote (by reciprocation) goodness. Thus, both types of gratitude share certain core elements.

But what then is the difference between both types of gratitude? The terms we use to distinguish both concepts indicate the following main difference: whereas the dyadic concept only involves gratitude for a gift, the triadic concept involves gratitude for a gift and to a benefactor.Footnote 22 Whereas dyadic gratitude construes the received good as a metaphorical gift, triadic gratitude does so in a literal sense — i.e. a gift received from an intentional agent. This difference implies that triadic gratitude, in contrast to dyadic gratitude, is not merely concerned with the gratuitous goodness of a gift but also with the benefactor’s intentions and sacrifices that presumably underlie it. Furthermore, the concern with perceived agency or lack thereof can shape the motivational impetus that often accompanies or flows from gratitude: triadic gratitude usually motivates to reciprocate to a benefactor, while dyadic gratitude usually motivates to promote and radiate goodness in a more general sense. Sometimes, however, triadic gratitude can also motivate to radiate and pay forward the good that we received; for example, our gratitude to Sofia can motivate us to help other colleagues in a similar way.

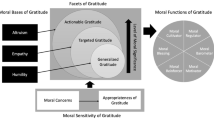

So to conclude, all gratitude experiences share certain core elements and can be thought of as forming a ‘field of gratitude experiences’. In this sense, we agree with McAleer (2012) that “there are not two kinds of gratitude here but one, sometimes aimed at targets, sometimes not” (p. 57). However, for some purposes a more specific classification of gratitude experiences might be useful. The binary classification into triadic and dyadic (sub-concepts of) gratitude is a case in point, which might prove helpful to study the different effects of both types of gratitude. Another potentially fruitful classification is a ‘spectrum of gratitude experiences’ in which the separation between self and other alters; this spectrum ranges from experiencing a clear separation between self and other at one end of the spectrum, to feelings of profound connection or even oneness at the other end (Elfers and Hlava 2016, p. 92; Hlava and Elfers 2014, p. 451).Footnote 23 But again, the different possible classifications of gratitude experiences are subordinate to the fact that they all share a common core.

4.3 Is Dyadic Gratitude a Useful Concept?

Since we consider concepts as mental tools which enable us to communicate about and get grip on reality, we should also investigate whether or not ‘dyadic’ gratitude is a useful concept. The analysis above indicates that this concept captures a set of experiences that share a common core among themselves; as such, the concept of dyadic gratitude enables us to articulate these experiences in thought and speech. Without (being ‘allowed’ to use) this concept, we would not be able to think and communicate about such experiences effectively — ‘conceptually handicapped’, as it were — and we would either have to use suboptimal alternative terms such as ‘appreciation’, or remain silent regarding such experiences. This argues against Fagley’s (2018) argument that dyadic gratitude is a vague concept which is not fine-grained enough for scientific research. Moreover, apart from its value in daily life, the concept of dyadic gratitude is also scientifically relevant; many psychologists who have demonstrated that ‘gratitude’ is associated with various positive psychosocial effects, have focused on the entire range of gratitude experiences — i.e. including both dyadic and triadic conceptualizations.Footnote 24 Thus, when Roberts (2004) argues that triadic gratitude is important because it enhances wellbeing and functions as an antidote to negative emotions, this also seems to apply to dyadic gratitude.

Another question, which might be particularly interesting for philosophers, is whether or not dyadic gratitude can be thought of as a virtue. The aforementioned positive psychosocial effects indicate gratitude its instrumental value, but is it also somehow intrinsically valuable? It lies beyond the scope of the present paper to answer this question in detail, but we believe that some of gratitude’s characteristics argue for its potential value as a virtue. First, dyadic gratitude does not just involve a pleasant feeling — as does joy or feeling glad — but it entails a reflective, receptive-appreciative attitude. In dyadic gratitude experiences we seem to open up to the world around us and become aware of what is valuable to us. Furthermore, dyadic gratitude involves a realization that the good in our lives should not be taken for granted, and an acknowledgement of our dependency on something other than ourselves. All these insights seems to further our self-understanding and sensed connection with the world around us. Moreover, dyadic gratitude experiences entail a motivational impetus to live in accordance with what is valuable to us, and to radiate and promote goodness. Based on these characteristics, it seems likely that dyadic gratitude experiences can contribute to (human) flourishing. This indicates that dyadic gratitude can be developed as a virtuous disposition or character trait.Footnote 25 Although these propositions should be investigated in detail, they strongly suggest that dyadic gratitude is a useful concept.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we have argued that dyadic gratitude — i.e. gratitude in absence of a benefactor — is a coherent concept. Some authors argue that ‘gratitude’ is by definition a triadic concept involving a beneficiary who is grateful for a benefit to a benefactor; these authors state that people who use the term gratitude in absence of a benefactor do so inappropriately — e.g. by using it as an interchangeable term for ‘appreciation’ or ‘being glad’. We believe that the conceptual analyses that underlie such statements have a strong linguistic focus and pay insufficient attention to the lived experience of gratitude. Thus, we have conducted a phenomenological analysis of several experiences in which people occasionally report feeling gratitude in absence of a benefactor. We have analysed and compared the constitutive experiential elements of these experiences. Informed by our phenomenological findings, we have argued that dyadic gratitude is a coherent concept that shares certain core elements with triadic gratitude.

Gratitude is an appreciative response that construes its object as a gratuitous good and as a (metaphorical) gift; it is characterised by a receptive-appreciative attitude, an awareness that we are in some sense dependent on something other than ourselves, and a motivational impetus to promote, celebrate and/or radiate goodness. Whereas the dyadic concept only involves gratitude for a gift, the triadic concept involves gratitude for a gift and to a benefactor — i.e. an intentional agent. This difference implies that triadic gratitude, in contrast to dyadic gratitude, is not merely concerned with the gratuitous goodness of a gift but also with the intentions and sacrifices that presumably underlie it. Finally, we have argued that dyadic gratitude is a useful concept because it enables us to think and communicate effectively about a set of experiences. Moreover, dyadic gratitude is also a scientifically and philosophically relevant concept; experiences of dyadic gratitude seem to be associated with various positive psychosocial effects, and it might be interesting to investigate under what conditions dyadic gratitude can be developed as a virtue. However, more research is needed regarding the potential value of dyadic gratitude; we hope that this paper provides a conceptual basis for such research and contributes to its advance.

Notes

In recent years, some advances have been made with regard to the conceptualization of gratitude, but debates regarding the benefactor condition have only intensified (Gulliford and Morgan 2021, p. 210).

For this reason, triadic gratitude has also been labeled ‘directed’ and ‘targeted’ gratitude (McAleer 2012; Rush 2020), whereas dyadic gratitude has also been termed ‘non-directed’ and ‘generalized’ gratitude (Lacewing 2016; Lambert et al. 2009). Besides, various other labels are being used to distinguish these concepts — a consensus regarding the use of standard terms has yet to be reached.

Some of these authors argue that a dyadic concept of gratitude is too vague and that a triadic conceptualization of gratitude seems a more fruitful approach to investigating gratitude as a virtue.

In section 3.1 we will elaborate on the distinction between the lived, pre-reflective experience that we are concerned with, and the post-reflective descriptions of experience that conceptual/linguistic analyses focus on.

The ‘three term construal’ indicates the benefactor, benefit and beneficiary.

Roberts (2004) focusses on atheists because they cannot attribute the benefit (the good weather) to the benevolent intentions of (a) God.

The article of Hlava and Elfers (2014) is an exception that is concerned with the lived experience of gratitude.

Zahavi (2015) points out that “on the one hand, we have the view that reflection merely copies the lived experience and on the other, we have the view that reflection distorts lived experience. The middle course is to recognize that reflection involves a gain and a loss” (p. 185). We subscribe to this latter view of reflection.

Zahavi (2019, 2020) criticizes Van Manen’s description of phenomenology in general and his interpretation of the phenomenological reduction in specific. We agree with Zahavi that Van Manen’s use of the terms ‘epoche’ and ‘reduction’ does not match the ways in which these terms were originally used by influential phenomenologists such as Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty. However, we believe that the strategies described by Van Manen are useful to become reflectively aware of central aspects of our lived experiences, and to refrain from imposing distorting components in our reflection. Moreover, Zahavi (2019, p. 904) criticizes Van Manen’s statement that phenomenology aims “to let a phenomenon (lived experience) show itself in the way that it gives itself while living through it” (van Manen 2017, p. 813) — i.e. that it aims to reproduce pre-reflective experience — and rightly points out that this would render phenomenology superfluous. Yet, in other work Van Manen (1997/2016, p. 36) explicitly argues that phenomenological descriptions should not only bring about a ‘reflexive re-living’ but also a ‘reflective appropriation’ of lived experience, meaning that it should make us reflectively aware of and enable us to articulate aspects of lived experience that we were previously not consciously aware of, and as a consequence further our understanding of the nature of that experience.

As Van Manen (2016) puts it: “Wonder is the unwilled willingness to meet what is utterly strange in what is most familiar. Wonder is the stepping back and let[ting] things speak to us, an active-passive receptivity to let the things of the world present themselves on their own terms.” (p. 223)

In phenomenological research this is sometimes called ‘thematic analysis’, with ‘themes’ referring to the experiential elements that make up lived experience (see Van Manen 1997/2016, pp. 78–95).

This description is based on a personal experience, but appears to resemble aspects of the experiences of astronauts who see planet earth from space: they report profound feelings of awe, (inter)connectedness with and gratitude for life on earth and a corresponding motivation to take care of it (Nezami 2017, p. 118).

We would like to stress that when a certain object is construed as a ‘gratuitous good’, this does not imply that the subject has had no influence on receiving this good. For instance, consider an athlete who has trained extremely hard for several years, pushing herself to the upper limits of her capabilities, and who might even expect herself to break a world record; such an athlete might nonetheless feel grateful when she finally does break this record. Here, her gratitude might be a response to the realization that this achievement has never been under her complete control (e.g. she might have suffered from an ill-timed injury), and/or that the conditions which enabled her to embark on this athletic journey should not be taken for granted — consider how few of us are born with the genetic make-up and/or social environment necessary to break a world record.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary the term ‘dependence’ has two related, yet subtly different meanings. First, dependence as “the quality or state of being influenced or determined by or subject to another”; we use this term as such, with ‘another’ referring to the broad category of ‘forces beyond one’s scope of complete control’. Second, dependence is also used as a synonym of 'reliance’, implying a sense of trust in the stability of a certain good; gratitude might sometimes include such a sense of trust (e.g. regarding being nurtured by the sun), but this is not always the case.

We want to stress that this motivation does not necessarily lead to corresponding actions.

Elfers and Hlava (2016) argue that dyadic gratitude often involves a recognition of our embeddedness in an interdependent relationship, as a result of which “other-care becomes self-care” (p. 66) and “self-interest transforms into the interest of the whole” (p. 126).

Here we intend to disentangle the notion of ‘dependency’ from its negative connotations, i.e. helplessness and a corresponding sense of immaturity, and instead focus on both its ‘technical’ and positive meaning: gratitude entails an implicit acknowledgement that we are in fact dependent on something other than ourselves — we are embedded in a natural and social world and get shaped by various incontrollable forces.

This lack of open receptiveness might also explain certain experiences in which we rationally realize that we should feel grateful for a particular gratuitous good, but fail to emotionally charge this insight with gratitude.

According to Wilson (1963), considering related cases (which are related to but distinguishable from the concept of interest) and borderline cases (of which it is unclear whether these are an instance of a concept) is useful to gain insight regarding a concept and its boundaries.

We justify using the term ‘gratitude’ in absence of a benefactor, but also acknowledge that some people (especially in modern western societies) feel a certain embarrassment or awkwardness with such use of this term. This embarrassment might result from the collapse of the religious frame of reference through which such experiences were formerly interpreted — namely gratitude in absence of a human benefactor as an appropriate response towards gifts received from God, the omnipresent benefactor. Thus, for some people the concept of dyadic gratitude is associated with a God in whom they do not believe (Van Tongeren 2016). Likewise, other personal and cultural views might influence the meaning and connotations attached to the term ‘gratitude’.

Some authors use the terms targeted gratitude for the triadic concept (see McAleer. 2012; Jackson 2016; Rush 2020) and generalized (Lambert et al. 2009) or non-directed (Lacewing 2016) gratitude for the dyadic concept. These terms reflect the idea that the main difference between both types of gratitude lies in their directedness or scope. McAleer (2012, pp 57) indeed argues that triadic gratitude always entails a narrow targeted focus, yet he stresses that dyadic gratitude is not restricted to a wide generalized focus but can also retain a narrow targeted focus on its primary object (the gift).

Elfers and Hlava (2016) distinguish three different types of gratitude on their spectrum: gratitude of exchange/benefit-triggered gratitude, gratitude of caring and transpersonal gratitude. Respectively, these three entail a focus on a tangible benefit, the value of a relationship and a ‘transcendent’ benefit marked by a feeling of interdependence. Their descriptions indicate that triadic gratitude is more often associated with the former two, and dyadic gratitude with the latter two; however, this is no one-on-one relationship. Moreover, the concept ‘gratitude of caring’ points out a grey area between triadic and dyadic gratitude; when we are grateful for (the quality of) our relation with someone, we might consider some of their benevolent intentions without ascribing the very existence of this relationship to such intentions. This makes it difficult to categorize this experience as either triadic or dyadic gratitude.

In fact, many psychologists pay little attention to the conceptualization of gratitude (Gulliford et al. 2013). It might be interesting to investigate the different effects of triadic and dyadic gratitude in further studies.

We argue that dyadic gratitude can be developed as a virtuous disposition, not that it is virtuous per se. We are aware that gratitude experiences and a grateful disposition might be accompanied by various risks — e.g. by distracting from human suffering in situations of injustice (see Jackson 2016). Thus, we believe that people need certain skills/knowledge and a concern for justice to develop gratitude in a virtuous manner.

References

Algoe, S.B. 2012. Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 6 (6): 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425.

Allen, S. 2018. The science of gratitude. Berkeley: Greater Good Science Center.

Bartlett, M.Y., P. Condon, J. Cruz, J. Baumann, and D. Desteno. 2012. Gratitude: Prompting behaviours that build relationships. Cognition & Emotion 26 (1): 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.561297.

Bartlett, M.Y., and D. DeSteno. 2006. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science 17 (4): 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x.

Carr, D. 2013. Varieties of gratitude. The Journal of Value Inquiry 47 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-013-9364-2.

Carr, D. 2015. Is gratitude a moral virtue? Philosophical Studies 172 (6): 1475–1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0360-6.

Dickens, L.R. 2017. Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 39 (4): 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638.

Elfers, J., and P. Hlava. 2016. The spectrum of gratitude experience. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41030-2.

Fagley, N.S. 2018. Appreciation (including gratitude) and affective well-being: Appreciation predicts positive and negative affect above the Big Five personality factors and demographics. SAGE Open 8 (4): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018818621.

Frijda, N.H. 1986. The emotions, 6th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Froh, J.J., R.A. Emmons, N.A. Card, G. Bono, and J.A. Wilson. 2011. Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies 12 (2): 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9195-9.

Gulliford, L., B. Morgan, and K. Kristjánsson. 2013. Recent work on the concept of gratitude in philosophy and psychology. The Journal of Value Inquiry 47 (3): 285–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-013-9387-8.

Gulliford, L., and Morgan, B. 2021. The concept of gratitude in philosophy and psychology: an update. ZEMO 4: 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42048-021-00103-w

Hlava, P., and J. Elfers. 2014. The lived experience of gratitude. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 54 (4): 434–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167813508605.

Hunt, M.W. 2022. Gratitude is only fittingly targeted towards agents. Sophia 61 (2): 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-020-00811-7.

Jackson, L. 2016. Why should I be grateful? The morality of gratitude in contexts marked by injustice. Journal of Moral Education 45 (3): 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1186612.

Jans-Beken, L., N. Jacobs, M. Janssens, S. Peeters, J. Reijnders, L. Lechner, and J. Lataster. 2020. Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15 (6): 743–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1651888.

Lacewing, M. 2016. Can non-theists appropriately feel existential gratitude? Religious Studies 52 (2): 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412515000037.

Lambert, N.M., S.M. Graham, and F.D. Fincham. 2009. A prototype analysis of gratitude: Varieties of gratitude experiences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 35 (9): 1193–1207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209338071.

Manela, T. 2016. Gratitude and appreciation. American Philosophical Quarterly 53 (3): 281–294.

Manela, T. 2018. Gratitude to nature. Environmental Values 27 (6): 623–644. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327118X15343388356356.

McAleer, S. 2012. Propositional gratitude. American Philosophical Quarterly 49 (1): 55–66.

Nezami, A. 2017. The overview effect and counselling psychology: astronaut experiences of earth gazing [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. City, University of London. Retrieved September 26, 2022, from https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17938/.

Petitmengin, C. 2006. Describing one’s subjective experience in the second person: An interview method for the science of consciousness. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 5 (3): 229–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-006-9022-2.

Roberts, R.C. 2004. The blessings of gratitude: A conceptual analysis. In The psychology of gratitude, ed. R.A. Emmons and M.E. McCullough, 58–78. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0004.

Rush, M. 2020. Motivating propositional gratitude. Philosophical Studies 177 (5): 1191–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01241-z.

Rusk, R.D., D.A. Vella-Brodrick, and L. Waters. 2016. Gratitude or gratefulness? A conceptual review and proposal of the system of appreciative functioning. Journal of Happiness Studies 17 (5): 2191–2212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9675-z.

Steindl-Rast, D. 2004. Gratitude as thankfulness and as gratefulness. In The psychology of gratitude, ed. R.A. Emmons and M.E. McCullough, 282–290. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0014.

Van Tongeren, P. 2016. Dankbaar: Denken over danken na de dood van God (2e druk). Klement.

Tudge, J.R.H., L.B.L. Freitas, and L.T. O’Brien. 2015. The virtue of gratitude: A Developmental and Cultural Approach. Human Development 58 (4–5): 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444308.

Van Manen, M. 1997/2016. Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315421056.

Van Manen, M. 2017. Phenomenology in its original sense. Qualitative Health Research 27 (6): 810–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317699381.

Van Manen, M. 2016. Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315422657.

Wilson, J. 1963. Thinking with Concepts, 31st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, A.M., J.J. Froh, and A.W. Geraghty. 2010. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review 30 (7): 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005.

Zahavi, D. 2015. Phenomenology of reflection. In Commentary on Husserl’s ideas I, ed. A. Staiti, 177–193. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110429091-011.

Zahavi, D. 2019. Getting it quite wrong: Van Manen and Smith on phenomenology. Qualitative Health Research 29 (6): 900–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318817547.

Zahavi, D. 2020. The practice of phenomenology: The case of Max van Manen. Nursing Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12276.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from The Netherlands Initiative for Education Research (NRO; Nationaal Regieorgaan Onderwijsonderzoek). The grant number is: 40.5.395.092.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest related to this piece of work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hebbink, N., Schinkel, A. & de Ruyter, D. Does Dyadic Gratitude Make Sense? The Lived Experience and Conceptual Delineation of Gratitude in Absence of a Benefactor. J Value Inquiry (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-023-09950-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-023-09950-9