Abstract

How do we learn to share? As contemporary Western folks, what do we share, under what conditions, and with whom? Through two personal “material stories,” our paper explores how archaeologists can think beyond capitalism when interpreting material worlds. We consider the dynamics (and limits) of sharing economies as an emerging form of collective production. Starting from the blunt force “consolidation” of a leading British archaeology department, we trace the subsequent fissures and spaces of opportunity created by this disruptive moment of neoliberal closure. We tell stories about the collective production of a replica lithic assemblage, and the construction of a community chicken hutch, to explore the intricacies of everyday sharing as an intentional means of resource creation. Through these two disparate case studies, we aim to not only demonstrate the complex social networks and object meanings generated by sharing (versus capitalist) economies, but also consider wider implications (both benefits and conflicts) generated through collective resource production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

If, as argued by Bertell Ollman, the “sprouts” of communism already lie concealed in capitalism (Ollman 2014: 76), where might these seedlings thrive? To what degree would they flourish within the cracks of our dominant socioeconomic paradigm? Or are these alternative models always in a process of emergence from within capitalism itself? Our paper draws from two case studies to explore contemporary sharing economies as both reactions to, and products of, late capitalism. The creation, acquisition, and use of resources can offer new opportunities for sharing economies; they can also generate bitter arguments over the limits of “ownership.” Sparked from a shared moment of blunt percussion—the attack on archaeology as a valid departmental subject within British universities—our two “object stories” follow along the resulting impact fissures of our subsequent lives. By explicitly adopting a narrative approach, we follow these new cracks that, for us, opened possibilities inside the solid mass of capitalism. We explore a range of imperfect ways that our social relations exist within and beyond commodification. In other words, our stories navigate the “relations of love, of solidarity, of co-operation, of dignity” (Holloway 2018: 205) that cannot be reduced to simple transactional exchange because, as observed by Pnina Werbner, “there is a motivation, a passion for something that creates organization, exchange, altruistic giving, all kinds of complex ways of behaving in ways of relation to other people” (Venkatesan et al. 2011: 240).

Neoliberalism within universities, and within archaeology as a discipline, is not new. It has in fact been embedded within its function from the very start (Wurst 2019: 169). Similarly, it has been argued that the role of institutions such as schools and universities is not so much to provide an education or encourage critical thinking, but to shape individuals to operate in the capitalist system within which we exist (Holloway 2010a: 916; Wurst 2019: 169). Drawing from wider ideas of “sharing economies,” our paper explores the related experiences of two members of a northern English university archaeology department in the throes of what can be euphemistically described as a “haircut” in order to demonstrate how the cracks formed by this stark transformation opened new opportunities for alternative economies. As Holloway (2010a: 918, 2010b: 11) has explained, the range of creative individual responses to neoliberal ruptures can seem disparate and ineffective. Nevertheless, these individual responses can also be understood as acts of resistance to the abstraction of our labor. Consequently, this paper offers two related “material stories” to explore individual responses to the rapid restructuring of an archaeology department, and how that transformation opened new pathways into sharing economies. John’s story is from the perspective of an early career archaeology technician; Eleanor’s considers how post-university life has opened up new questions on the nature of “sharing.” Our narratives are intended as reflections upon moments or opportunities of resistance as tools for occupying, and thriving within, the cracks inside the framework of late capitalism (Holloway 2010b: 13). Through the manufacture of a knapped lithic assemblage and the construction of a community chicken hutch, we explore how ideas of “ownership,” “sharing,” and “trade” characterize both the dynamics and limits of alternative economies.

John’s Story: “There Ain’t No Justice, Just Us” (Ruthless Rap Assassins 1990)

While neoliberalism within universities and archaeology departments has already been discussed (Wurst 2019: 169), for this author (John Piprani) it was in 2020 that it felt as though the landscape was changing. I was in my fourth year of a Fixed Term Contract (FTC) as part-time Archaeology Technician at the University of Manchester. I had also completed a fifth rolling one-year FTC as part-time Visiting Lecturer at the University of Chester. While my contracts were precarious, retrospectively there did appear to be some continuity, so why did it feel like change?

At the time, the British Government had formally proposed a 50% grant cut to university teaching of archaeology to start with the 2021/22 academic year. The government saw archaeology as a “high cost” arts subject and therefore not a “strategic priority” for funding in the prevailing political climate (Bakare and Adams 2021). Both University Archaeology United Kingdom (UAUK) and the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA) were collaborating to lobby the government to reclassify archaeology as a strategic priority (CIfA 2021). While this potential government funding cut would have implications for how universities could deliver archaeology teaching, it happened at the same time as university staff at all levels were managing the effects of the global Covid-19 pandemic. At both of my institutions, the senior management process created further issues. At the University of Manchester, the Samuel Alexander Arts Building was occupied by students in protest of senior management’s treatment of both students and FTC staff (Fig. 1).

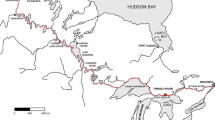

At my second institution, things were no better. A number of University of Chester archaeology colleagues with full-time permanent contracts were under threat of losing their jobs. The University College Union (UCU) and students were fighting 27 compulsory redundancies across seven departments including archaeology (UCU 2021). There were similar stories for archaeology at both the University of Leicester and the University of Sheffield (Fig. 2).

It could be argued that the combination of Covid and potential government cuts created a situation where universities were in an intractable position. However, for the archaeology department at Manchester our problems had started well before this juncture.

Between 2008 and 2016, I completed a Masters and PhD at Manchester in what was a medium-sized archaeology department of 12 full time academics and a part-time (2.5 days) technician. In 2016, as I was finishing my doctorate, the department was “rationalized.” The University of Manchester made a strategic decision to raise the entry grades for archaeology admission, which resulted in fewer students and equated directly to a drop in fee income. To manage this self-inflicted financial shortfall, the archaeology department had to be given a “haircut,” ultimately losing five academics, four of whom were professors. As I write, we are now a department of 5.5 full time posts, 1.5 of which are FTCs.

While Covid and the potential government cuts presented an immediate and challenging reality, I believe that the departmental “haircut” provides insight into how the senior management understands the university as an institution, and therefore evaluates the discipline of archaeology. From my own experience as a student, and now an academic and technician, I developed an appreciation for the university as an institution structured to conduct research and deliver teaching. In contrast, the senior management sought to establish the university’s ranked position within a larger national and international “knowledge economy.” The development of this knowledge economy model can perhaps be understood in relation to larger shifts within the UK sector, from the introduction of fees in the late 1990s and arrival of student loans in the early 2000s. In this explicitly financialized context archaeological research and teaching are increasingly configured as products within a transactional relationship between the university, departmental staff, and students. Although union actions have offered one commonly recognized form of workplace resistance, this pathway still accepts the underlying neoliberal institutional framework—our labor will be inevitably abstracted, so our responses must primarily focus upon the terms and conditions of that abstraction (Holloway 2010a: 922). As discussed, the ongoing financialization and rationalization of archaeology within English universities is part of a larger process of creeping neoliberal expansion into evermore sectors (see Wurst 2019:169). Nevertheless, this first case study explores the human experience of this ongoing process and how new kinds of social relationships were able to develop within the resulting cracks.

As the archaeology technician at Manchester, it is a paradox that most of the equipment I deal with is digital while my area of expertise is prehistoric stone tools from the Early Upper Palaeolithic of Britain. Through the process of completing my PhD I gained a good knowledge of how to analyze and understand stone tools (Piprani 2016). However, in contrast to this high-level analytical ability I was still a novice when it came to making stone tools, only able to produce the most basic of scrapers. The ability to make stone tools was something I had spent a long time trying to learn, and realize with hindsight that my lack of success was primarily due to a lack of regular practice. This lack of regular practice stemmed from a lack of access to knappable materials, since knappable stone (flint) sources in Britain are primarily located in the south and east and I live in the northwest. It was because of the above factors that in around 2016 I became interested in historic-period Australian Aboriginal glass and ceramic Kimberley Points (Fig. 3).

Glass and ceramic Kimberley Points are spearheads and knives produced by Aboriginal people of the northern Kimberley region between the late-1800s and 1980s (Akerman et al. 2002: 13). Although Kimberley Points were traditionally made from stone, later ceramic and glass examples were made from settler rubbish and became highly desirable commodities in both Aboriginal communities and Western museum collections (Harrison 2006: 63). Most large UK museums have a collection of Kimberley Points, and the Manchester Museum has a dozen or so in its stores. I was interested in these Kimberley Points because their production methods had been recorded ethnographically in both written texts and photographs, Manchester Museum had a collection I could access and interrogate, and—most importantly—they were made from materials I could easily acquire living in a northwest post-industrial city. Freely available “raw” materials (albeit glass and ceramic rather than stone) provided me with the opportunity to practice knapping regularly.

A quick internet search revealed that Kim Akerman, the preeminent scholar on Kimberley Points, had all his work freely available on < Academia.edu>. Before downloading, the website asked if I wanted to let the academic know why I was interested in his work, which I did in a few short lines. To my pleasant surprise, Kim emailed me back and directed me to a couple of relevant papers (Akerman 1979b; Akerman et al. 2002), two useful twentieth-century books (Idriess 1937; Porteus 1931), and also attached two of his own teaching Powerpoints for good measure. This information gave me a good grasp of the technical processes involved, and it felt like time for a museum visit.

The points in the Manchester Museum were finely made from nineteenth- and twentieth-century bottle glass. Due to the bottle manufacturing processes involved, this older glass is uneven in thickness and contains bubbles. Fragments of this kind of old bottle glass do bear a resemblance in thickness and form to stone flakes, and along with the sharp edges I can now see how Aboriginal stone users may have recognized these features. Fortunately for me there is a twentieth-century bottle dump not far from my home, with lots of broken bottle glass eroding out from overblown tree roots and ejected from surrounding animal burrows. I had found my period material, and through the making process began to realize that the thickness of the old glass provides it with an internal cohesion that makes it much more forgiving than thinner modern glass.

Through this production process, I became more interested in my source materials. A departmental colleague, Eleanor Conlin Casella, is an historical archaeologist with a good knowledge of the history and dating of glass bottle production. She had also excavated Kimberley Points while working in Australia, so it was clear we needed to have a chat. Our enthusiasm was dampened a little by the fact that Eleanor already had a good idea that she was one of the academics who would ultimately be declared “redundant” and leaving the department. After giving me a “beginners” guide on how to understand nineteenth- and twentieth-century historic glass bottles, Eleanor asked if I could make her a couple of Kimberley Point replicas for her teaching collection. By this time, I was a competent enough stone tool maker to oblige.

Perhaps a month or so later, Eleanor’s archaeologist friend, Denis Gojak, visited from Australia and she showed him the points I had made for her. Denis told Eleanor that he had lots of nineteenth-century bottle glass back in Australia that I could have free of charge. He had a project budget to dispose of it, and was happy to dispose of it in my direction. While this was a kind offer, I already had my local period glass supply so I cheekily asked if he could send me some Australian glass, but also “throw in” some fencing wire, kangaroo ulnae, and local hardwoods. These were all production materials that Kim Akerman had explained were used in the Aboriginal Kimberley Point making process, and obviously difficult to obtain in north west Britain. By coincidence, Denis’ friend John Pickard researched fencing wire in Australia (Pickard 2007, 2010), and was heading out for a field trip to New South Wales in the following few weeks. Denis provided John with my “shopping list” and that was the last I thought of it for a good while.

In October 2017 I received a message from Eleanor saying that she had brought a package back from Australia for me. We met up in the Mansfield Cooper Building laboratory, and she handed over two samples of hardwoods, about a dozen lengths of fencing wire, and two kangaroo ulnae. This was amazing and very moving considering I had not met either Denis or John in person. The materials had all been inventoried and tagged, and after John had found the kangaroo, dead by the side of the road, he removed and rendered the arms to provide me with the ulnae. I wrote a blog post about it at the time, entitled Community of Hope: <https://wp.me/p7Wwbe-WT> after a song by the artist Polly Jean Harvey as this seemed exactly appropriate. As an archaeology department, we were in the process of being economically rationalized by the university, and yet a collection of difficult to obtain objects gathered from the other side of the world, by people I had never met, landed on my laboratory bench in Manchester. Each of these people had drawn from their personal knowledge, abilities, experience, or connections to furnish my needs. What was going on here?

John Holloway (2010b: 21) describes a crack as “the perfectly ordinary creation of a space or moment in which we assert a different type of doing.” Thinking about this experience through the lens of John Holloway’s work suggests that the pursuit of my interest in learning to make stone tools was just such a space or moment. Indeed, using the university laboratory space to play with this freely gathered material was indeed a different type of “doing” than the normal digital, spreadsheet, scheduling type tasks that normally filled my 2.5 days. I left behind my digital workload, and instead engaged in a material process. It represents a crack, and the subsequent involvement in the process of Kim, Eleanor, Denis, and John each further widened that crack. By engaging others, my material process developed into a social process. To return to Holloway (2010b: 22) “the point about cracks is that they run, and they may move fast and unpredictably.”

Eleanor finished working at Manchester shortly after delivering my “things,” and the things themselves seemed to form a coherent record of the above events. I could not bring myself to make them into tools, so instead I made them into an exhibition. As you entered our Mansfield Cooper building, you were confronted by a display case next to a snack vending machine. The display case had looked sad and unloved for a good while. So I asked its curator, my colleague Kostas Arvanitis, if I could use it, and he obliged. My idea was to display the twentieth-century books that Kim had recommended along with my gifted “things” and some of the replica points I had made. I originally intended this exhibition as the technological story of Kimberley Points. However, the exhibition evolved into a materialization of my appreciation to Kim, Eleanor, Denis, and John, integrated into the technological story of the points themselves. While Eleanor was no longer there in person, it seemed appropriate that a photograph of her would still greet every visitor entering the building (or wanting to buy a snack from the vending machine). The telling of the social process became a material exhibition emphasizing again how these cracks run fast and can move in unpredictable directions (Holloway 2010b: 22).

I discussed at the beginning the precarity of my FTC employment. The feelings and the idea of precarity is based upon an uncertainty as to where I (an early career member of an academic archaeology department) will be able to fit within the evolving knowledge economy. When my FTC ends I will become part of a “reserve army” of intelligent, highly educated and skilled people queuing up for this role within the university. Within this knowledge economy approach, I would extend the financializing terminology to argue that it is in fact a “buyers-market” and ending a FTC allows the university to reassess the terms and conditions of the position in relation to the quantity and quality of applicants. While others have discussed the way neoliberalism is embedded within the university (Wurst 2019:169–170) it was really as the above process unfolded—and I began to reflect upon the effects upon colleagues such as Eleanor—that I began to feel the landscape changing, and also started to recognize the cracks appearing.

An important dimension to my experience was the unexpected social relationships that developed within my Kim-Eleanor-Denis-John (and now Kostas) community. This development of social relationships also explains why at the University of Chester both staff who receive wages and students who pay fees protest together how the university prioritises a rationalized economic relationship for all those people in the department. I would argue that for both students and staff, the teaching and learning relationship is experienced in social terms: as knowledge and idea sharing. The same is true from the students occupying the Samuel Alexander Building at Manchester. They are protesting how senior management treats them and their fees, as well as the university staff and their contracts. The students at both of these institutions emphasize the importance of the student/staff social relationship in the face of the senior management’s imposition of a knowledge economy. The students, staff, and scholars discussed above are behaving as social human beings instead of calculating machines.

So, what does all this mean? This case study has focused upon how initiating the delivery of knowledge (through teaching), but also abilities (to occupy a building), experience (to make a stone tool), and connections (to acquire valuable materials), combine to simultaneously generate social relationships. Asking for, and the giving of, resources becomes a powerful mechanism for the development of these social links, and it is certainly true that I have benefitted from them. I have no doubt that many readers have had similar experiences. Kim Akerman’s research and knowledge, freely given, facilitated my own flint knapping ability. And I have been able to integrate and share these skills and understandings within my own teaching practice. The gifted materials became one part of the exhibition articulating an alternative set of values from those of the knowledge economy. I love that this example of a “crack” greeted everyone entering the building for six months. The story of the development of this community has become the content for this publication, and the thing I have enjoyed doing the most was a materials-based workshop developed and delivered for the 2018 National Permaculture Convergence. It provided an Australian Aboriginal inspired perspective on how we can start to understand waste materials differently. Most recently I have shared the above story as a 50-minute episode on an archaeology student run podcast.

To follow Polly Jean Harvey, this experience and these relationships mean that I feel situated within a “community of hope.” I am connected to people who share my interests and have gone to significant effort to help me develop them. This kind of behavior engenders a feeling in me to offer the same, not simply in direct return to the listed members of the above community, but also beyond it. In contrast to my precarious FTC situation, this “sharing economy” gives me power and agency. Being able to draw upon my own knowledge, skills, and experience does not just help others, but it provides me a form of validation and showcase for my learned skills, as well as allowing me to actively develop and expand my community. The development of this community was not conscious, and perhaps because of this, it has sprouted organically and grown within and beyond the knowledge economy within which I sit. I have no doubt that many readers have similar examples. I absolutely recommend joining the University and College Union, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, and for UK archaeology departments the UAUK. These formal professional groups need our support to look after our interests. However, as illustrated above, we each also have a personal estate we can draw upon. By sharing our personal knowledge, abilities, experience, or connections we have agency and can develop community. Being part of this kind of sharing community provides support as we find ourselves edged to the margins of the neoliberal knowledge economy. I will conclude with another musical reference, this time from the Ruthless Rap Assassins, three musicians who grew up literally on the margins of the University of Manchester campus: “when you’re living on the edge you have to do what you must. There ain’t no justice, just us.”

Eleanor’s Story: the Great Chicken War

“If a Cohousing community doesn’t work socially, why bother?” (Durrett 2015: 9). Communities of hope require careful and continuous maintenance. Practicing everyday life within the “cracks” of capitalism, intentional communities offer alternative models for sharing common values and material resources. But regardless of their size or shape, it can be difficult to sustain a sharing economy. These “communities of hope” negotiate their basic existence within the dominant capitalist paradigm, and conflicts frequently arise over the nature of both “sharing” and “ownership” (Holloway 2018). My story questions the limits and opportunities of alternative economies by exploring how the process of collective resource production may itself generate socioeconomic fractures.

Following my 2018 redundancy (or “haircut”) from the University of Manchester, I relocated to Australia and joined a Cohousing community. Originally developed in Denmark during the late 1960s, Cohousing is based upon a strata title model of privately owned houses clustered around collectively owned spaces, common buildings, and community resources (Durrett 2022; McCamant et al. 1994). While each specific Cohousing group maintains its own unique design and legal structure, a loose network of these intentional housing communities can be found across Europe, North America, and Australia. Cohousing communities operate like an intensive homeowner association, adopting a self-consciously hybrid space of opportunity to dominant models of housing ownership. Internal cohesion is explicitly promoted through frequent organized social activities (group parties, weekly shared meals, camping weekends, and regular management meetings) plus collectively owned material goods – typically a shared laundry facility and large kitchen/dining area, but also cooking equipment, building tools, lawnmowers, and play equipment. Requests for the purchase of new resources and the organization of scheduled social events are all presented monthly as agenda items at the regular management meetings for group discussion and consensus-based decision. Although explicitly designed to facilitate a nonhierarchical and collective approach to the acquisition and use of Cohousing resources (see Durrett 2015), in practice this decision-making process has sometimes exposed (if not exacerbated) bitter underlying disagreements over the very nature of capital within my particular sharing economy.

When established in the early 1990s, my Cohousing community initially acquired its material goods through an eclectic mix of sources. Some residents donated their laundry machines to the Common House as they moved into their new homes, and others began storing their tools in the shared workroom for general borrowing. A subgroup of residents banded together to purchase a television and VCR for the Common House. Another subgroup of parents bought a trampoline for the outdoor recreational area. Cohousing community funds were used for soft goods, crockery, appliances, and fittings inside the Common House, plus an expanded range of workshop tools and gardening equipment.

Chickens were introduced in this early stage, with the chicken subgroup jokingly self-named the “Chicken Barons.” An allotment of community garden land was designated for the chicken run. The Chicken Barons gathered a small flock and built a simple hutch (in true Australian style) out of recycled timber and sheets of corrugated iron. Over the next couple of decades, the overall community evolved as children grew-up, folks rented their houses, and new owners bought into Cohousing. The community not only amassed more shared material resources over time, but also many of the early assets subtly shifted from private to collective ownership—with repairs, upgrades, and replacements funded by Cohousing rather than original owners. Membership of the Chicken Barons similarly shifted, and the flock eventually incorporated a mix of individually and collectively purchased birds.

The Chicken War erupted over a 2018 management meeting agenda item that applied for AUD$2,000 of Cohousing funds to replace the 25-year-old chicken hutch (Fig. 4). While a seemingly random focus for a community meltdown, this building request (and the broader existence of the Cohousing chickens) rapidly materialized into passionate arguments over competing philosophies of capital ownership within this sharing economy. In accordance with the principles and by-laws of this Cohousing community, resolution of the funding application required a community consensus decision in the first instance, and a simple majority vote of house owners if no consensus could be achieved. As debates grew increasingly heated, and various participants blocked consensus, the Chicken Barons’ agenda item carried over into numerous formally scheduled management meetings, in addition to a specially appointed “sub-committee” tasked with workshopping potential conflict resolutions. Over the next three months, opinions roughly clustered Cohousing residents (both owners and tenants) into three loosely defined positions: the private, the public, and the neutral/negotiated models of resource ownership.

One side of this fracture defended a limited model of collective ownership. Espousing a “thin end of the wedge” argument, these proponents defined Cohousing as a strata title community ultimately established around private property. The chicken run had never been formally approved or collectively funded in accordance with the Cohousing by-laws, and therefore constituted individual assets outside the bounds of this sharing economy. The cost of their feed and egg collections were only shared among the Chicken Barons. Therefore, maintenance, repair, or replacement of their associated infrastructure was an issue for their owners, not this intentional community. Ultimately, as one steadfast opinion leader asked: Were the chickens actually pets?

The opposing group defined Cohousing as an intentional community, with foundational emphasis on the concept of “community.” In their perspective, the chickens constituted a collective asset in harmony with the other shared resources. Although the eggs and feed “belonged” to the Chicken Barons, the overall flock and its associated infrastructure was equal to other Cohousing assets—equal to the workshop tools, television, laundry, kitchen equipment, and trampoline. Replacement of the chicken hutch therefore constituted a collective enterprise, and replacement of the chicken hutch should be undertaken from community funds as part of this ethos of “sharing.”

A third spectrum of opinions existed between these private versus public models of ownership. Positions ranged from soft leans toward either side, to a defensively neutral “I don’t care.” Ultimately, this third group clustered around ideas for a split funding model: a proportion of collective funds would pay for the new chicken hutch, with the remainder covered by the Chicken Barons. These participants emphasised the need for an architectural plan and full economic costing to be circulated to support collective consensus on the funding request. Over the numerous community meetings and emails, this conciliatory group emphasized the need for “flexibility” in both sharing economies and concepts of “ownership.”

In practice, this foundational economic tension exposed a continuum of values, with Cohousing residents arranged along a spectrum of beliefs over the nature, function, and meaning of community resources. In the end, the bitter conflict was partially (if fleetingly) resolved. Two retired residents—both members of the Chicken Barons—decided to partner over the construction of the new hutch as a fun mini-building project. Their final spectacular and overdesigned Chicken Palace (Fig. 5) used recycled timber and cost less than 1/3 of the original funding request.

But like a Russian Doll, The Chicken War revealed increasingly nested debates over the basic nature of capital and Cohousing. Did house renters (as temporary residents) hold the same decision-making power as Cohousing homeowners? What was the proportion of renters versus owners within the Chicken Barons? Should renters, with no Cohousing capital investment, have equal ability to determine investment of collective resources within this “sharing” economy? That last question itself raised further passionate debates over the spectre of an internal “class” system within the community. And on a deeper (and frequently emotive) ontological level, was this Cohousing group originally established or intended as a non-capitalist community? Or was it always more of a “neighbor/friends” strata-title housing group, with privately owned houses enjoying access to a limited range of shared facilities?

Following resolution of The Chicken War, a simmering discontent has spawned periodic eruptions of this ideological conflict. Community arguments have focused on an update of existing solar panels, the introduction of charging docks for electric vehicles, ownership of pets (particularly cats) on-site, appropriate/permitted uses of Common House amenities, and replacement of decayed sections along the community’s boundary fences. For a good while, these tensions fostered a gloomy collective atmosphere, with house ownership standing “as gatekeeper” for those “who make it unthinkable for us to question the ‘this is mine!’ upon which capital stands” (Holloway 2018: 200). One agenda item circulated for a recent formal meeting directly questioned the basic function of a sharing economy within Cohousing, arguing that “to lean upon the goodwill of others acting in a voluntary capacity is not an effective survival strategy.”

And yet, the underlying clash over concepts of capital ownership has not destroyed the shared values and practices of this Cohousing community. In fact, the tension itself has stimulated more explicit collective reflection on the deeper purpose of “community making.” The homeowner most dedicated to private property ownership has recently withdrawn from group social and managerial activities, and is certain they “lost” The Chicken War. Meanwhile, other neighbors/friends have responded to the conflict by reaffirming their commitment to this sharing economy, and created events for improving and revitalizing group cohesion. Christmas and mid-season group meals are celebrated with potlucks and games inside the Common House. A new householder organized a well-attended workshop day for brainstorming collective strategies for carbon emission reduction. A renter has just started growing kale along the collective pathway, and over this winter the Chicken Barons introduced two new chickens into the Cohousing flock. This community of hope remains a messy beast, an ideal, a deeply negotiated practice.

My story does not tell of either failure or success. Instead, I am wondering about the degree to which an alternative sharing economy has actually been achieved, and what it might become? The cracks of capitalism are always emergent, always splitting along new fractures. Celebrating its 30th Anniversary in May 2021, one founding resident described Cohousing as a long-term marriage in the midst of its mid-life crisis:

By design, a Cohousing community is different than an individualistic or hierarchical society. In Cohousing it’s more or less impossible to have a pecking order; and instead of getting orders or giving orders, you dialogue a topic and decide together (Durrett 2015: 17).

Conclusions

How do alternative economies operate? Starting with a reflection on the increasingly neoliberal knowledge economy of Britain’s universities and the blunt fractures of its painful legacy, our paper explores how people have begun to mobilize “sharing” as an emerging economy. These acts of everyday reciprocity help knit participants together into larger communities of hope. Sharing, like love, “is ubiquitous. We cannot just turn our faces away from its prevalence and its purchase and its importance and significance in the worlds in which we work” (Venkatesan et al. 2011: 245). Production of knapped Kimberley Points initiated an informal community dedicated to shared archaeological knowledge and resources. Collective use of Cohousing resources has produced an intentional community dedicated to a form of shared living. And yet, these complex social networks do not exist within a utopian vacuum. Deep questions over the nature, value, and function of “ownership” continue to influence the success (and limits) of these alternative economies. In practice, communities of hope exist. They negotiate complex networks of incomplete and discontinuous, yet ever present, impact fissures within the solid stone of capitalism. And they are vibrant spaces of both mutual support and fractious argument, for “it is only by integrating our doing into the sociality of doing that we can maintain our flight from capital” (Holloway 2018: 200). Through our contemporary “object stories” we offer a contemplation on the messy inner workings of both the cracks of capitalism and the cracks emergent from capitalism.

References

Akerman, K. (1979). Flaking stone with wooden tools. The Artefact 4(3):79–80.

Akerman, K., Fullagar, R., and Van Gijn, A. (2002). Weapons and wunan: production, function, and exchange of Kimberley Points. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1:13–42.

Bakare, L. and Adams, R. (2021, 6 May). Plans for 50% funding cut to arts subjects at universities “catastrophic” Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/may/06/plans-for-50-funding-cut-to-arts-subjects-at-universities-catastrophic; accessed August 2022.

CIfA. (2021). Higher Education Threats. https://www.archaeologists.net/advocacy/toolkit/higher_education_threats; accessed August 2022.

Durrett, C. (2022). Cohousing Communities: Designing for high-functioning neighbourhoods. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

Durrett, C. (2015). Happily Ever Aftering In Cohousing: A handbook for community living. Habitat Press and McCamant and Durrett Architects, Nevada City, CA.

Harrison, R. (2006). An artefact of colonial desire? Kimberley points and the technologies of enchantment. Current Anthropology 47(1):63–88.

Holloway, J. (2010a). Cracks and the crisis of abstract labour. Antipode 42(4):909–923.

Holloway, J. (2010b). Crack Capitalism. Pluto Press, London.

Holloway, J. (2018). Revolt or revolution or get out of the way, capital! In Bonefield, W. and Tischker, S. (eds.), What is to be Done?: Leninism, anti-Leninist Marxism and the question of revolution today. Routledge, London, pp. 196–206.

Idriess, I. (1937). Over the Range: Sunshine and shadow in the Kimberley. Angus and Robertson, Sydney.

McCamant, K., Durrett, C., and Hertzman, E. (1994). Cohousing: A contemporary approach to housing ourselves. 2nd ed. Ten Speed, Berkeley.

Ollman, B. (2014). Communism: the utopian "Marxist vision" versus a dialectical and scientific Marxist approach. In Brincat, S. (ed.), Communism in the 21st Century, Vol. 1. Praeger, Santa Barbara, pp. 63–81.

Pickard, J. (2007). The transition from shepherding to fencing in colonial Australia. Rural History 18:143–162.

Pickard, J. (2010). Wire fences in colonial Australia: technology transfer and adaptation, 1842–1900. Rural History 21:27–58.

Piprani, J. (2016). Penetrating the “Transitional” Category: an Emic Approach to Lincombian Early Upper Palaeolithic Technology in Britain. University of Manchester, Manchester.

Porteus, S. D. (1931). The Psychology of a Primitive People: A study of the Australian Aborigine. Edward Arnold, London.

UCU. (2021, 26 April). Student protest at University of Chester over 27 job cuts. https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/11519/Student-protest-at-University-of-Chester-over-27-job-cuts; accessed August 2022.

Venkatesan, S., Edwards, J., Willerslev, R., Povinelli, E., and Perveez, M. (2011). The anthropological fixation with reciprocity leaves no room for love: 2009 meeting of the group debates in anthropological theory. Critique of Anthropology 31(3):210–250.

Wurst, L. (2019). Should archaeology have a future? Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 6(1):168–181.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Casella, E.C., Piprani, J. Communities of Hope: Sharing Economies and the Production of Material Worlds. Int J Histor Archaeol 28, 208–222 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00682-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00682-3