Abstract

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a disease with limited evidence-based treatment options. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) offer benefit in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but their impact in HFpEF remains unclear. We therefore evaluated the effect of MRA on echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters in patients with HFpEF by a systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, clinicaltrials.gov, and Cochrane Clinical Trial Collection to identify randomized controlled trials that (a) compared MRA versus placebo/control in patients with HFpEF and (b) reported echocardiographic, functional, and/or systemic parameters relevant to HFpEF. Studies were excluded if: they enrolled asymptomatic patients; patients with HFrEF; patients after an acute coronary event; compared MRA to another active comparator; or reported a follow-up of less than 6 months. Primary outcomes were changes in echocardiographic parameters. Secondary end-points were changes in functional capacity, quality of life measures, and systemic parameters. Quantitative analysis was performed by generating forest plots and calculating effect sizes by random-effect models. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed through Q and I2 statistics. Nine trials with 1164 patients were included. MRA significantly decreased E/e′ (mean difference − 1.37, 95% confidence interval − 1.72 to − 1.02), E/A (− 0.04, − 0.08 to 0.00), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (− 0.78 mm, − 1.34 to − 0.22), left atrial volume index (− 1.12 ml/m2, − 1.91 to − 0.33), 6-min walk test distance (− 11.56 m, − 21 to − 2.13), systolic (− 4.75 mmHg, − 8.94 to − 0.56) and diastolic blood pressure (− 2.91 mmHg, − 4.15 to − 1.67), and increased levels of serum potassium (0.23 mmol/L, 0.19 to 0.28) when compared with placebo/control. In patients with HFpEF, MRA treatment significantly improves indices of cardiac structure and function, suggesting a decrease in left ventricular filling pressure and reverse cardiac remodeling. MRA increase serum potassium and decrease blood pressure; however, a small decrease in 6-min-walk distance is also noted. Larger prospective studies are warranted to provide definitive answers on the effect of MRA in patients with HFpEF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a clinical entity for which few evidence-based treatments exist [1]. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), which represent a cornerstone treatment for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), failed to decrease mortality in HFpEF patients in a large, multi-center trial [2]. Nevertheless, the significant criticism pertaining to the trial’s design and execution [3, 4], combined with the paucity of other relevant, large data have resulted in uncertainty regarding the use of MRA in HFpEF. A small number of well-performed randomized studies have reported positive results with the use of MRA in HFpEF when assessing cardiac function by echocardiographic or patients’ functional status [5,6,7,8,9].

Still, the most recent European Society of Cardiology Guidelines state that “evidence that MRA improve symptoms in these patients is lacking”, while no reference is made to the reported effects of MRA on cardiac function and structure, as well as other systemic parameters [1]. On the other hand, US guidelines take a more definitive, though guarded stance (IIB recommendation) [10], in view of the positive impact of MRA observed on ventricular remodeling [11], favorable adaptations in echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function, and subgroup analysis of a secondary hospitalization endpoint from a clinical trial [12, 13]. Given that a significant body of literature has been published since the last relevant meta-analysis of randomized trials [14,15,16,17,18], a new meta-analysis on the topic seems timely and warranted. Inclusion of data on functional and systemic parameters, apart from echocardiographic indices, would further strengthen the rationale for performing the meta-analysis.

The objective of the current study was to critically assess the effect of MRA on echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters in adult patients with HFpEF included in randomized controlled trials.

Methods

The present study was conducted according to the PRISMA statement (Table A1-Appendix) [19]. The review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Number: CRD42018104929) www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018104929, Accessed 18 August 2018.

Identification and selection of studies

MEDLINE, EMBASE, clinicaltrials.gov, and Cochrane Clinical Trial Collection were searched on June 15, 2018 with a combinatorial approach (Boolean operator “AND”) of three broader search terms. The broader search terms were derived using the Boolean operator “OR” between synonyms for “heart failure,” “preserved ejection fraction,” and “mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.” Detailed descriptions of the terms used for MEDLINE and EMBASE searches are outlined in the Appendix Tables A2 and A3. The search was restricted to the period from January 1, 2000 onwards, out of concern for a high risk of imprecision in the clinical diagnosis of HFpEF prior to 2000. Only articles written in English were eligible, while there was no restriction regarding publication status. The reference lists from previous systematic reviews relevant to our topic were hand-screened for studies [11, 14, 20], whereas references of the included articles were screened for additional studies. If needed, authors were contacted to request unpublished original papers or further details not available on the official version.

Study eligibility criteria included: (a) comparison of MRA (spironolactone, eplerenone, canrenone) with placebo/control; (b) adult patients diagnosed with HFpEF; (c) follow-up ≥ 6 months, as administration of MRA for a shorter period was considered unlikely to produce significant functional and echocardiographic changes; and (d) report of the outcomes of interest (Table 1). HFpEF definition included patients with HF symptoms and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 45%. There was no cut-off for natriuretic peptides or cardiac abnormalities as these criteria have been recently established by guidelines and would have excluded most of the older trials. We excluded studies if they included patients with previous history of myocardial infarction or compared MRA with another active comparator. Ethical approval was not required, as no patients were recruited.

The search was independently performed by two reviewers (MML and TN). End-note was used to remove duplicates. All titles and abstracts were screened individually by all four reviewers, in order to select those that met the inclusion criteria. Differences in assessment of eligibility between reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias (RoB) within studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. The assessment was performed at the study level and regarded components recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for randomized trials, namely randomization sequence generation, treatment allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of outcome data, and selective outcome [21]. For each component, trials were categorized as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Studies that were deemed to be at high risk of bias would only be included in the systematic review but not in the meta-analysis.

Risk of bias across studies was evaluated by assessing publication bias and selective reporting within studies. In order to explore publication bias (meta-bias), unpublished information was meticulously searched so that it could be incorporated to quantitative analysis. Α list of the conference databases that were searched to this end is given in Table A4 (Appendix). We assessed quality of evidence for outcomes using GRADE criteria [22].

In addition, protocol registries (clinicaltrials.gov and PROSPERO) were scanned to assess selective outcome reporting. All four reviewers performed their personal assessment and any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

A systematic approach was used to extract the relevant variables from the selected studies. The variables for which data were sought are shown in detail in Table A5 (Appendix) and regarded study identity and design, patient population, intervention, and outcomes. Outcome parameters were divided into three groups: echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters. Echocardiographic parameters were prioritized over the other parameters as primary outcomes, as they are systematically measured and reported in relevant studies. Furthermore, several echocardiographic indices (LAVi, E/e′) have been recognized as significant predictors of prognosis in patients with HFpEF [23, 24], thus entailing clinical implications to our analysis. Volumetric echocardiographic parameters that were not indexed were not included. Quality of life (QoL) changes should have been estimated with either Kansas City Questionnaire (KCCQ) or the Minneapolis Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHFQ). All four reviewers extracted study characteristics and data input was cross-validated between reviewer databases.

Qualitative and statistical analysis

Data were combined in a systematic review, forest plots and, if appropriate, in a meta-analysis. We set three studies as the minimum number for quantitative synthesis of data in a meta-analysis for each study parameter. Given that all outcomes were continuous variables, mean differences were used as effect measures. For those parameters, which were indexed to diverging bases across studies (i.e., left ventricular mass index, LVMI) or quantified by different measurement techniques (i.e., BNP and NT-proBNP), standardized mean differences by the method of Hedges were used. When not available, standard deviations were derived from confidence intervals according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions or from median with interquartile ranges according to Wan et al. [21, 25]. Missing standard deviations for the difference between treatment and control group were also calculated according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [21].

Our data was expected to be heterogeneous due to the relatively small sample sizes and the diversity in study design. Consequently, analysis was performed with random effect models. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Q statistic; however, due to its limited power to rule out heterogeneity, a p value threshold of 0.10 was used. A quantitative analysis of the impact of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic was also performed. I2 values > 50% were considered as highly heterogenous. In order to evaluate the effect of imputing standard deviations of within-group changes, a sensitivity analysis for different values of correlation coefficients (0.7, 0.9, and 0.8 or calculated based on given study data) was performed.

Although performance of three subgroup analyses to explore heterogeneity had been pre-specified (multi-center vs single-center studies, studies with high percentage of women vs even gender distribution and studies with high vs low baseline use of diuretics), subgroup analysis was not considered feasible due to the small number of studies. For the same reason, we also decided not to perform meta-regression analyses and funnel plots with the trial mean differences to explore meta-bias. All p values were two-tailed with statistical significance set at 0.05 (if not otherwise specified) and confidence intervals (CI) computed at 95% level. All analyses were performed with the use of Stata 15 Software (StataCorp LLC, Texas, US).

Results

Identified and eligible studies

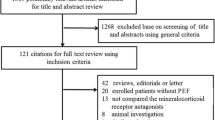

The number of identified and screened studies is indicated in Fig. 1.

Our initial search identified 1253 studies from 2000 onwards; after removal of duplicates, screening of titles, abstracts, and full-texts and adding studies from previous analyses up to 2014, 12 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis (Table 2). Of these, three studies were not suitable for data extraction, which resulted in nine studies amenable for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

The studies enrolled 1164 patients (588 patients in the MRA and 576 in the control/placebo arm) who were followed for up to 18 months. Of the included trials, seven included patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction ≥ 50% and eight were placebo controlled. In seven studies, the administered MRA was spironolactone, while in the remaining two studies eplerenone. The baseline characteristics and the reported clinical, echocardiographic parameters and systemic parameters are indicated for each study in Table A6 (Appendix).

Risk of bias within studies

During quality assessment, issues regarding random sequence generation were observed in 5 studies. Protocol deviations, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting of results were not observed in any of the selected studies. Details of RoB assessment are given in Fig. 2.

Risk of bias across studies

Multiple conference databases as well as protocol registries were scanned for other studies that could be relevant to our meta-analysis. Our search did not produce any results that could indicate any concerns regarding publication or selective outcome reporting biases.

Results of individual studies and synthesis of results

Echocardiographic parameters

Echocardiographic parameters were frequently measured and reported among studies. Eight studies reported E/A and E/e′, while seven studies provided data on deceleration time (DT). Six studies included data on left ventricular mass index (LVMi) and ejection fraction (LVEF) and four on left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD). Finally, values for left atrial volume index (LAVi) were provided by five studies.

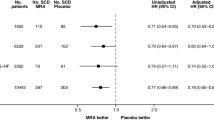

MRA compared to placebo/control significantly decreased E/e′ (mean difference [MD]: − 1.37; 95% CI: − 1.02 to − 1.72; comparison p < 0.001; heterogeneity p = 0.437; I2 = 0.0%), E/A (MD: − 0.04; 95% CI: − 0.08 to 0.0; comparison p = 0.046; heterogeneity p = 0.491; I2 = 0.0%), LVEDD (MD: − 0.78 mm; 95% CI: − 1.34 to − 0.22; comparison p = 0.006; heterogeneity p = 0.632; I2 = 0.0%), and LAVi (MD: − 1.12 ml/m2; 95% CI: − 1.91 to − 0.33; comparison p = 0.005; heterogeneity p = 0.389; I2 = 3.1%) (Fig. 3).

On the contrary, MRA compared to placebo/control did not significantly affect DT (MD: − 8.38 ms; 95% CI: − 21.76 to 5.00; comparison p = 0.220; heterogeneity p < 0.001; I2 = 85.5%), LVEF (MD: 0.62%; 95% CI: − 0.65 to 1.88; comparison p = 0.340; heterogeneity p = 0.155; I2 = 37.7%), and LVMi (standardized MD: − 0.12; 95% CI: − 0.50 to 0.27; comparison p = 0.550; heterogeneity p < 0.001; I2 = 84.5%) (Appendix Fig. 1).

Functional parameters

Functional parameters were assessed and reported in less than 50% of included studies. Four studies reported maximum rate of oxygen consumption (VO2 peak), 6-min walk test distance (6-MWD), and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. Quality of life (QoL) metrics were assessed and presented in five studies.

MRA compared to placebo/control, did not significantly increase VO2 peak (MD: 1.22 ml/kg/min; 95% CI: − 0.33 to 2.77; comparison p = 0.124; heterogeneity p < 0.001; I2 = 90.8%), while they significantly decreased 6-MWD (MD: − 11.56 m; 95% CI: − 21 to − 2.1; comparison p = 0.016; heterogeneity p = 0.522; I2 = 0.0%) (Fig. 4).

Among other measures of functional status, NYHA class was treated as a categorical rather than a continuous variable in three out of four studies, rendering the pooling of effect estimates unfeasible. Regarding QoL measures, two studies used the KCCQ, in this way not fulfilling the pre-specified cut-off for quantitative synthesis. Three studies used the MLWHFQ; MRA use did not significantly affect MLWHFQ (MD: − 1.15; 95% CI: − 3.00 to 0.693; comparison p = 0.221; heterogeneity p = 0.597; I2 = 0.0%) (Appendix Fig. 2). Furthermore, as the two questionnaires have inverse directions for high-quality (MLWHFQ scale of 0–105 with higher scores indicating lower QoL and KCCQ scale of 0–100 with higher scores indicating higher QoL) pooling of estimates with standardized effect sizes was considered inappropriate.

Systemic parameters

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were common outcomes among the included studies, as they were reported in seven of them. On the other hand, serum potassium and blood levels of natriuretic peptides (BNP/NT-proBNP) were uncommon outcomes, as they were measured in three and four studies, respectively.

Among HFpEF patients, MRA treatment compared to placebo/control significantly decreased systolic (MD: − 4.75 mmHg; 95% CI: − 8.94 to − 0.56; comparison p = 0.026; heterogeneity p = 0.001; I2 = 74.6%) and diastolic blood pressure (MD: − 2.91 mmHg; 95% CI: − 4.15 to − 1.67; comparison p < 0.001; heterogeneity p = 0.350; I2 = 10.4%) (Appendix Fig. 3). Additionally, MRA significantly increased serum levels of potassium (MD: 0.23 mmol/L; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.28; comparison p < 0.001; heterogeneity p = 0.539; I2 = 0.0%), but did not affect blood levels of BNP/NT-proBNP (standardized MD: − 0.00; 95% CI: − 0.29 to 0.28; comparison p = 0.970; heterogeneity p = 0.015; I2 = 64.5%) compared with placebo/control (Appendix Fig. 4).

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analysis

The effects of MRA on echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters of patients with HFpEF seemed to be largely insensitive to different levels of correlation coefficient (0.7, 0.9, and 0.8 or calculated based on given study data) for imputation of standard deviations of within-group changes (Table A7).

Discussion

The main findings of this meta-analysis on the effect of MRA in patients with HFpEF are: MRA (a) positively affect significant echocardiographic indices of cardiac structure and function, (b) slightly decrease 6-MWD, (c) increase levels of serum potassium, and (d) decrease blood pressure.

Our study adheres to PRISMA reporting guidelines, while our conclusions are based on evidence of moderate to high quality (GRADE). Moreover, we exclusively included randomized controlled trials of patients with symptomatic HFpEF and not patients with asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction, HFrEF or myocardial infarction, as previous studies on the topic had done [11, 14, 20]. This was crucial in obtaining a comparable patient sample and analyzing multiple outcomes with low level of heterogeneity. Additionally, as we screened studies up to June 2018, we included in our quantitative analysis four new, randomized studies, which contributed approximately 50% of the overall population and increased statistical power of analysis and significance of findings [15,16,17,18]. Furthermore, our study meticulously studied a range of echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters, thus providing the only, to date, comprehensive review of these effects of MRA in the HFpEF patient population.

Effect of MRA on echocardiographic parameters

Our study provides high-quality evidence to support that MRA can exert significant, positive effects on diastolic cardiac function (E/e′) and structure (LVEDD, LAVi) of HFpEF patients. Beneficial effects of spironolactone on clinical endpoints (HF hospitalizations) in these patients have been previously reported [2]; however, failure of one landmark trial to demonstrate superiority of spironolactone regarding the prespecified primary outcome has resulted in low MRA use among real-world HFpEF patients [23]. Elevated E/e′ and left ventricular (LVEDD) and left atrial dimensions (LAVi) have all been recognized as predictors of adverse clinical outcome in this patient population [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Whether these indices represent markers of unchangeable, progressive disease or of potentially reversible pathophysiological mechanisms remains poorly elucidated; however, our current understanding of the natural process of the disease and the close correlation of these parameters with LV filling pressure suggests that the latter is the most probable scenario underlining the therapeutic potential of MRA [31]. Hence, the above echocardiographic parameters could be considered as surrogate markers of clinical outcomes and, until otherwise proven, therapeutic targets. Furthermore, decrease of LVEDD and LAVi also suggests that MRA induce reverse remodeling.

Effect of MRA on functional parameters

MRA use did not confer significant improvements in QoL indices in the present meta-analysis, though the neutral results may have been driven by the small number of studies reporting QoL parameters, alongside the use of two different questionnaires. Changes in NYHA class, though clinically significant, were not reported as numerical variables in the included studies and thus could not be quantitatively synthesized. Finally, inconsistencies in the effect of MRA on functional capacity of HFpEF patients were reported. Exercise capacity, objectively assessed by peak VO2, was increased by an increment of 1.2 ml/kg/min, though the result was statistically insignificant. Nonetheless, evaluation of this effect is hindered by high heterogeneity. Conversely, MRA led to significant, though mild decrease (11.5 m) in 6MWD in these patients. This effect, which was largely driven by the results of a single study [8], is contradictory to the other, physiological and clinical, effects of MRA in patients with HFpEF. Thus, further investigations are warranted to confirm the effect of MRA on functional parameters.

Effect of MRA on systemic parameters

MRA use results in significant increases in serum potassium levels. In particular, serum potassium increased in the intervention group (from weighted mean 4.20 ± 0.0 to 4.39 ± 0.03 mmol/L) but decreased in the control group (from weighted mean 4.21 ± 0.03 to 4.17 ± 0.06 mmol/L). These findings are of clinical importance as previous studies have demonstrated that lower levels of serum potassium are associated with adverse outcome [32, 33], while high-normal levels of potassium are accompanied by the most favorable prognosis in HF patients [34]. On the other hand, MRA treatment also leads to significant decreases in blood pressure. Systolic (weighted mean 136.5 ± 8.4 to 130.7 ± 7.5 mmHg for intervention vs. 136.2 ± 6.4 to 135.2 ± 5.5 mmHg for control) and diastolic blood pressure (weighted mean 77.5 ± 2.7 to 74.6 ± 3.0 mmHg for intervention vs. 77.9 ± 3.6 to 77.2 ± 4.4 mmHg for control) decreased in both groups; however, magnitude of decrease was greater in the intervention group. This effect, which has been previously reported [35], is encouraging as multiple studies support that treating hypertension is of high relevance in HFpEF [36, 37].

Clinical significance and future perspective

As mentioned above, the only multi-center study to date investigating the effect of MRA on outcomes failed to meet its primary endpoint [2]. One must not, however, disregard the signals of efficacy observed with the use of spironolactone compared with placebo (reduction of HF hospitalizations by 17%), as well as the regional disparities that may have confounded the results [3, 4]. Particularly, patients enrolled on the basis of the hospitalization criterion were much younger, with fewer coexisting conditions and a lower risk profile compared with patients enrolled on the basis of elevated natriuretic peptides [3]. Moreover, the former also had a lower event rate, a finding which contradicts a large body of HF literature. The majority of patients from Russia and Georgia were enrolled in the hospitalization stratum. Furthermore, based on the blood analyses of 366 patients participating in the study who were reporting to take the drug at 12 months, canrenone (spironolactone’s metabolite) concentrations were undetectable in a significantly higher proportion of participants from Russia than from the United States and Canada (30% vs. 3%), strongly suggesting that the trial results obtained in Russia may not reflect the true therapeutic response to spironolactone [4]. Importantly, a post hoc analysis demonstrated that spironolactone seemed to benefit patients in the Americas but not those in Russia or Georgia [3].

Nonetheless, given that new trials aiming to evaluate the effect of MRA on hard clinical endpoints are not expected for several years [38], effect of MRA on other clinically relevant parameters, such as the ones reported herein, may have important implications in informing physicians’ decision to administer MRA in HFpEF patients. Due to the relatively small study populations and the limitations of the studies in the field, several issues pertaining to the effects of MRA in HFpEF remain unsettled. Namely, the question whether the lack of significant effect of MRA on some studied parameters is due to type II error needs to be clarified via future larger studies. This pertains in particular to parameters which are either of high clinical significance (QoL, NYHA, BNP, LVMi) or/and for which a trend is reported in the present study (DT, VO2peak). New studies will also be needed to confirm or reject the unexpected result of decrease in 6-MWD with use of MRA. This finding is paradoxical as exercise capacity has been shown to increase (not decrease) alongside the aforementioned changes in cardiac function/structure [39].

Limitations

Our study shares the same weaknesses with previous systematic reviews in the field. First, heterogeneity in the criteria employed to diagnose HFpEF and in the design of studies represent major limitations, as they may have resulted in heterogeneous patient populations. Sample size was relatively small; thus, type II error may explain some of the negative findings of the analysis. Furthermore, study outcomes were not consistently reported in all included trials. All these limitations may in part be responsible for significant heterogeneity observed among the pooled analyses for some outcomes. Moreover, this meta-analysis was not performed on a patient level but collected aggregate data from randomized studies with different designs. This fact precluded performance of subgroup analysis in specific subpopulation. Although most included studies enrolled patients based on the same ejection fraction threshold (≥ 50%), other distinct inclusion criteria varied across studies. Hence, extrapolation of results to the overall HFpEF population should be done with caution.

Despite these caveats, this meta-analysis may have significant therapeutic implications. In view of aggregate favorable effects with no sound evidence of adverse effects, MRA treatment should be considered as a treatment option for patients with HFpEF.

Conclusions

In patients with HFpEF, MRA use leads to significant improvements in important indices of cardiac structure and function, potentially indicating a decrease in LV filling pressure and reverse cardiac remodeling. MRA significantly increase serum potassium, decrease blood pressure, but also decrease 6-MWD. Although this study represents the most comprehensive, to date review of MRA effects on echocardiographic, functional, and systemic parameters in HFpEF, larger prospective studies are warranted to provide definitive answers.

References

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Members A/TF, Reviewers D (2016) 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 18(8):891–975

Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM, Investigators TOPCAT (2014) Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 370(15):1383–1392

McMurray JJ, O'Connor C (2014) Lessons from the TOPCAT trial. N Engl J Med 370(15):1453–1454

de Denus S, O'Meara E, Desai AS, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Leclair G, Jutras M, Lavoie J, Solomon SD, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Rouleau JL (2017) Spironolactone metabolites in TOPCAT - new insights into regional variation. N Engl J Med 376(17):1690–1692

Mottram PM, Haluska B, Leano R, Cowley D, Stowasser M, Marwick TH (2004) Effect of aldosterone antagonism on myocardial dysfunction in hypertensive patients with diastolic heart failure. Circulation 110:558–565

Mak GJ, Ledwidge MT, Watson CJ, Phelan DM, Dawkins IR, Murphy NF, Patle AK, Baugh JA, McDonald KM (2009) Natural history of markers of collagen turnover in patients with early diastolic dysfunction and impact of eplerenone. J Am Coll Cardiol 54:1674–1682

Deswal A, Richardson P, Bozkurt B, Mann DL (2011) Results of the randomized aldosterone antagonism in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction trial (RAAM-PEF). J Card Fail 17:634–642

Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, Kraigher-Krainer E, Colantonio C, Kamke W, Duvinage A, Stahrenberg R, Durstewitz K, Löffler M, Düngen HD, Tschöpe C, Herrmann-Lingen C, Halle M, Hasenfuss G, Gelbrich G, Pieske B, Aldo DHFI (2013) Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA 309:781–791

Kurrelmeyer KM, Ashton Y, Xu J, Nagueh SF, Torre-Amione G, Deswal A (2014) Effects of spironolactone treatment in elderly women with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Card Fail 20:560–568

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C (2017) 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:776–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025

Cheng M-L, Wang C-H, Shiao M-S, Liu MH, Huang YY, Huang CY, Mao CT, Lin JF, Ho HY, Yang NI (2015) Metabolic disturbances identified in plasma are associated with outcomes in patients with heart failure: diagnostic and prognostic value of metabolomics. J Am Coll Cardiol 65:1509–1520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.018

Chen Y, Wang H, Lu Y, Huang X, Liao Y, Bin J (2015) Effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Med 13:10

Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Heitner JF, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Rouleau JL, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, McKinlay SM, Pitt B (2015) Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 131(1):34–42

Pandey A, Garg S, Matulevicius SA, Shah AM, Garg J, Drazner MH, Amin A, Berry JD, Marwick TH, Marso SP, de Lemos JA, Kumbhani DJ (2015) Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on cardiac structure and function in patients with diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc 4(10):e002137

Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, Shah SJ, Deswal A, Anand IS, Fleg JL, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD (2015) Prognostic importance of changes in cardiac structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and the impact of spironolactone. Circ Heart Fail 8(6):1052–1058

Kosmala W, Rojek A, Przewlocka-Kosmala M, Wright L, Mysiak A, Marwick TH (2016) Effect of aldosterone antagonism on exercise tolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 68(17):1823–1834

Upadhya B, Hundley WG, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Kitzman DW (2017) Effect of spironolactone on exercise tolerance and arterial function in older adults with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Geriatr Soc 65(11):2374–2382

Kosmala W, Przewlocka-Kosmala M, Marwick TH (2017) Association of active and passive components of LV diastolic filling with exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: mechanistic insights from spironolactone response. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.007

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Berbenetz NM, Mrkobrada M (2016) Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 16(1):246

Higgins J, Green S (2008) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.0.0 ed: Cochrane Collaboration. Available online at: https://training.cochrane.org. Accessed 18 Aug 2018

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336(7650):924–926

Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, Anker SD, Crespo-Leiro MG, Harjola VP, Parissis J, Laroche C, Piepoli MF, Fonseca C, Mebazaa A, Lund L, Ambrosio GA, Coats AJ, Ferrari R, Ruschitzka F, Maggioni AP, Filippatos G (2017) Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail 19(12):1574–1585

Donal E, Lund LH, Oger E, Bosseau C, Reynaud A, Hage C, Drouet E, Daubert JC, Linde C, Investigators KR, Investigators KR (2017) Importance of combined left atrial size and estimated pulmonary pressure for clinical outcome in patients presenting with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 18(6):629–635

Nauta JF, Hummel YM, van der Meer P, Lam CSP, Voors AA, van Melle JP (2018) Correlation with invasive left ventricular filling pressures and prognostic relevance of the echocardiographic diastolic parameters used in the 2016 ESC heart failure guidelines and in the 2016 ASE/EACVI recommendations: a systematic review in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 20(9):1303–1311

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135

Persson H, Lonn E, Edner M, Baruch L, Lang CC, Morton JJ, Ostergren J, RS MK, Investigators of the CHARM Echocardiographic Substudy-CHARMES (2007) Diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved systolic function: need for objective evidence: results from the CHARM echocardiographic substudy-CHARMES. J Am Coll Cardiol 49:687–694

Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Baicu CF, Massie BM, Carson PE, Investigators I-PRESERVE (2011) Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 124:2491–2501

Banerjee P, Motiwala A, Mustafa HM, Gani MA, Fourali S, Ali D (2016) Does left ventricular diastolic dysfunction progress through stages? Insights from a community heart failure study. Int J Cardiol 221:850–854

Donal E, Lund LH, Oger E, Hage C, Persson H, Reynaud A, Ennezat PV, Bauer F, Drouet E, Linde C, Daubert C, investigators KR (2015) New echocardiographic predictors of clinical outcome in patients presenting with heart failure and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a subanalysis of the Ka (Karolinska) Ren (Rennes) study. Eur J Heart Fail 17(7):680–688

Rodrigues PG, Leite-Moreira AF, Falcão-Pires I (2016) Myocardial reverse remodeling: how far can we rewind? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310(11):H1402–H1422

Ahmed A, Zannad F, Love TE, Tallaj J, Gheorghiade M, Ekundayo OJ, Pitt B (2007) A propensity-matched study of the association of low serum potassium levels and mortality in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 28(11):1334–1343

Krogager ML, Eggers-Kaas L, Aasbjerg K, Mortensen RN, Køber L, Gislason G, Torp-Pedersen C, Søgaard P (2015) Short-term mortality risk of serum potassium levels in acute heart failure following myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 1(4):245–251

Hoss S, Elizur Y, Luria D, Keren A, Lotan C, Gotsman I (2016) Serum potassium levels and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 118(12):1868–1874

Bazoukis G, Thomopoulos C, Tse G, Tsioufis C (2018) Is there a blood pressure lowering effect of MRAs in heart failure? An overview and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 23(4):547–553

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, Belhani A, Forette F, Rajkumar C, Thijs L, Banya W, Bulpitt CJ, HYVET Study Group (2008) Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 358:1887–1898

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck-Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Rydén L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker-Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA (2013) 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 34:2159–2219

SPIRRIT study. Protocol available online at: www.clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed 22 August 2018

Chan E, Giallauria F, Vigorito C, Smart NA (2016) Exercise training in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 86(1–2):759

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO database registration number CRD42018104929

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 11073 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kapelios, C.J., Murrow, J.R., Nührenberg, T.G. et al. Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on cardiac function in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Fail Rev 24, 367–377 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-018-9758-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-018-9758-0