Abstract

In 1933 Margaret Lasker, a biochemist who worked at the labs of Montefiore Hospital in New York, developed an accurate method for the differentiation between pentosuria and diabetes. Research into pentosuria, and mostly its genetic aspects, became Lasker’s lifelong passion. Since research was not part of her job description, she conducted the chief part of her study in her home kitchen. Lasker’s extensive and personal correspondence with her patients and their families may be the secret key for her success in maintaining a prolonged research career against all odds. Laker’s last article was published in 1955 in Human Biology, presenting data on 72 cases of pentosuria, which occurs almost exclusively in Ashkenazi Jews. More than half a century later, and long after Lasker was gone, her well kept data and family records allowed the discovery of two mutations in the DCXR gene, by Mary-Claire King and her team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Morris Enklewitz (1900–1972) was an adjunct physician in Montefiore Hospital. Enklewitz and Lasker published six articles together between 1933 and 1938. Enklewitz also published three articles as sole-author between 1934 and 1936. Later, he worked as the secretary of the Medical Board of the New York City Employees’ Retirement System and, as far as we know, did not continue to conduct research.

See Lasker (1950, p. 485). Lasker used the term l-xyloketose, while most researchers refer to the same pentose as l-xylulose. In this article, we will use the more common term.

Erich Nassau to Lasker, 5 July 1959, Margaret Lasker’s Scientific Correspondence and Papers, in the possession of Prof. Mary-Claire King, Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle; hereafter LCP. See also Enklewitz and Lasker (1938).

As Dr. N. R. Blatherwick, of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, stated: “From June 6, 1934 to March 1, 1936, we examined 130,985 specimens of urine. These specimens were from applicants for life insurance, home office employees and field employees … [and] 31 individual cases of pentosuria were found” (Lasker et al. 1936, p. 248). See also: Knox (1958, p. 390).

Literature includes a number of reports of insulin-induced hypoglycemia episodes in patients with pentosuria; see Hiatt (2011, p. 15).

See the mass letter from Arno Motulsky and Mary-Claire King to individuals with pentosuria, 14 November 2010, LCP.

On the distinction between "heroic" science stories and "politically-correct" science stories—their implicit assumptions and the respective discourse they may create—see Milne (1998).

Interview with anthropologist Gabriel Lasker, Margaret Lasker’s son, by his daughter Anne Lasker, 26 February 1993, p. 23; hereafter GLI. We thank Anne Lasker for sharing the interview with NK.

It is worth mentioning that such bars were not confined to the Western world. In Japan, for example, marriage bars were prohibited only in 1985. For different explanations as to why marriage bars came into being, see Jacobsen (2007, p. 417).

GLI, p. 19.

Lasker to Eli Lilly and Company, 14 May 1956, Margaret Lasker’s private archive, in the possession of her grandson, Ted Lasker, Detroit, Michigan; hereafter MLPA.

Levenson also mentioned that during the 1930s an African-American woman was hired at Montefiore, at a time when most American hospitals would not consider employing African-Americans or women (p. 155).

Because of his Jewish heritage, Lichtwitz was dismissed from his position in Berlin by the Nazi regime and emigrated to the United States.

Henry Kelly to Mrs. Bruno Lasker, 23 January 1936, MLPA.

Gabriel Ward Lasker went on to get a PhD in physical anthropology from Harvard University and later became a well-known figure, serving as the editor of Human Biology for 35 years (1953–1987), the same journal in which he himself published his first article (Bogan 2003). For the role of familial collaboration in science, see Opitz et al. (2016); Richmond (2012).

Gabriel declared that he was "extremely interested in pentosuria," Gabriel Lasker to Nelson F. Chambers, 7 September 1935, MLPA. See also Lasker (1999, pp. 14–16).

Eugenics Record Office, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Historical Collections. Archives. https://www.cshl.edu/archives/institutional-collections/eugenics-record-office/. Accessed 28 July 2020.

Charles Davenport to Gabriel Lasker, 6 January 1936, MLPA. Gabriel remained interested in pentosuria; see Gabriel Lasker to Margaret Lasker, 5 July 1943, 23 September 1943, and 7 October 1943, MLPA.

A draft of an application for a grant, probably 1956 [no exact date], MLPA.

It seems that the term xyloketosuria was preferred by Human Biology and American Journal of Clinical Pathology. In her 1936 article in Human Biology, the term l-xyloketosuria was used as well, while pentosuria appeared in parenthesis. In the remainder of Lasker’s publications as well as those of other researchers, the term used is pentosuria.

Lasker to Sidney Smith, 27 August 1954, MLPA.

For example, her correspondence with Dorothy Bardfield lasted at least twelve years. In her last publication (1955), Lasker mentioned many patients whose follow-up lasted more than twenty years.

Lasker to Ethel R. Emmich, 31 August 1953, MLPA.

Elaine Solomont to Lasker, 17 October 1961, MLPA.

Frances Siegel to Lasker, 30 June 1952; Lasker to Frances Siegel, 14 November 1952; Frances Siegel to Lasker, 4 December 1952, MLPA.

Harry Gordon to Lasker, 19 May 1967, MLPA.

Sidney Smith to Lasker, 25 August 1954, MLPA.

She received a grant from the Committee on Scientific Research of the American Medical Association (Lasker 1941) and also $350 from the American Academy of Arts and Science in 1956, see letter from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences to Lasker, 18 May 1956, MLPA.

Lasker to Sidney Smith, 27 August 1954, MLPA.

Sidney Smith to Lasker, 11 October 1962, MLPA.

Sidney Smith wrote seven of his letters to “Dear Cousin Margaret” between August 1954 and August 1963; Frances Siegel wrote fourteen of her letters to “Dear Aunt Margaret” from November 1952 to December 1959; Barbara Siegel wrote three letters to “Dear Aunt Margaret”, 27 July 1953-26 July 1955; Dorothy Bardfield wrote three letters to “Dear ‘Aunt’ Margaret,” 7 May 1952–17 November 1960, MLPA.

Lois, Harry, Lauren, and Davy [no last name] to Lasker, May 1968, MLPA.

Sidney Smith to Lasker, 25 August 1954, 22 October 1959, MLPA. A Hotray is a food warmer.

Lasker to Frances Siegel, 14 November 1952, MLPA.

Elaine Solomont to Lasker, 5 January 1958; Lois to Lasker, 1959 [no exact date], MLPA.

Mae Gould to Lasker, 16 July 1957, MLPA.

Elaine Solomont to Lasker, 25 August 1961, MLPA.

For example, Lasker wrote: “It was good to have your letter bringing me up to date with news of the family”, Lasker to Mrs. Goldstein, 31 January 1954, MLPA.

Dorothy Bardfield to Lasker, 7 May 1952, MLPA.

See, for example, Barbara Siegel to Lasker, 27 July 1953, and seven letters from Sidney Smith to Lasker, 30 August 1955–27 July 1959, MLPA.

Barbara Siegel to Lasker, 27 July 1953; Lasker to Flora Brody, 6 February 1953; Lasker to Ethel R. Emmich, 18 August 1953; Lasker to Flora Brody, 6 February 1953, MLPA.

Frances Siegel to Lasker, 5 November 1952, MLPA.

Flora Brody to Lasker, 1959 [no exact date], MLPA.

Lasker to Harry Zimmerman, 10 July 1951, MLPA.

The term sticky floor was coined by the sociologist Catherine White Berheide to describe the discriminatory patterns that keep workers, mainly women, in the lower ranks of the job scale, with lower pay and less power and prestige (Harlan and Berheide 1994).

Herndon described, with two collaborators, an X-linked intellectual disability syndrome with muscle hypoplasia and spastic paraplegia that is called Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (OMIM 300523). Herndon was later considered a controversial figure for taking part in the North Carolina eugenic sterilization program

As far as we can determine, Lasker did not receive this fellowship.

Lasker to Lionel S. Penrose, 12 April 1945, PENROSE/3/12/9, L. S. Penrose Papers, Wellcome Library. https://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C_Rb2023786_SMargaret%20Lasker_Orightresult_U_X2?lang=eng&suite=cobalt. Accessed 8 June 2021.

The Virginia Apgar papers, U.S. National Library of Medicine - https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/Collection/CID/CP, accessed 18 January 2019. Virginia Apgar to Lasker, 1962 [no exact date], MLPA. The other female colleague that Lasker was in touch with was Elizabeth B. Robson from the Galton Laboratory, University College, London.

Lasker to Dr. Elizabeth B. Robson, [no date]; Lasker to Dr. Russell Weiser, 12 October 1953; Lasker to Dr. C. Nash Herndon, 11 February 1954, MLPA.

Application for a grant [1956], MLPA.

Lasker to Dr. Russell Weiser, 12 October 1953, MLPA.

Lasker to Victor E. Levine, 26. February 1956; Levine to Lasker, 14 March 1956; Lasker to Levine 20 March 1956, MLPA. Lasker and Levine did not succeed in writing the proposed book.

Lasker to Levine, 1959 [no exact date], MLPA.

Irene Delmar, "Have You Heard?" Herald Statesman, 5 March 1957, MLPA.

Personal communication from Peter Gilmartin, Margaret Lasker's grandson, 29 May 2015.

Mary-Claire King is the discoverer of BRCA1, the first gene linked to a higher-than-average chance of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer. While it seems obvious now that genes can be tied to cancer, at the time King conducted her studies, this idea was too radical to have many supporters (Angier 1993).

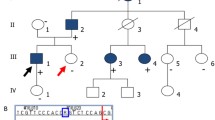

Pedigrees of Pentosuric Families, October 1959, LCP.

Gerty and Carl Cory, the 1947 Nobel Prize laureates in Physiology or Medicine, when working at Washington University in St. Louis as equal partners in the laboratory, Gerty Cory’s salary was ten percent of that paid to her husband, even though Gerty was responsible for many of their original ideas (Rubin 2016). On the different roles men and women played in genetic laboratories, see Dietrich and Tambasco (2007), Satzinger (2004), Stamhuis and Vogt (2017).

Lasker to Harry Zimmerman (Montefiore Hospital), 10 July 1951, MLPA.

For example, she presented her work at a meeting of the Association of Physical Anthropologists in 1952 and at the annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics in 1953. See her application for a grant, [no date, but probably 1956], MLPA.

For the American Medical Association, see: Lasker (1941, p. 51n.). For the Academy of Arts, see the document dated 20 March 1956, MLPA.

Application, 10 June1949; Robert Hockett (Sugar Research Foundation) to Lasker, 27 July 1949; Application, 18 March 1951; Lasker to Harry Zimmerman (Montefiore Hospital), 10 July 1951, MLPA.

Across the Atlantic, the home laboratory of British botanist Agnes Arber provides an interesting parallel (Schmid 2001).

References

Abir-Am, Pnina G., and Dorina Outram, eds. 1989. Introduction, Uneasy Careers and Intimate Lives: Women in Science, 1789–1979, 1–16. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ainley-Gosztonyi, Marianne. 1989. Field Work and Family: North American Women Ornithologists, 1900–1950. In Uneasy Careers and Intimate Lives – Women in Science 1789–1979, ed. Pnina G. Abir-Am and Dorina Outram, 60–76. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Angier, Natalie. 1993. Scientist at Work: Mary-Claire King; Quest for Genes and Lost Children. New York Times, 27 April, Section C, p. 1.

Anonymous. 1934. How the Laboratories of the Medical Division Function. Montefiore Echo November, 20(7): 1–2.

Anonymous. 1935. Pentosuria. Montefiore Echo. August-September 21 (4–5): 1–2.

Bliss, Michael. 2017. The Discovery of Insulin. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bogan, Barry. 2003. In Memorium: Gabriel Ward Lasker (April 29, 1912–August 27, 2002). American Journal of Physical Anthropology 121: 195–197 https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/34278/10224_ftp.pdf?sequence=1

Brush, Stephen. G. 1978. Nettie M. Stevens and the Discovery of Sex Determination by Chromosomes. Isis 59: 163–72. Rpt. in History of Women in the Sciences - Readings from Isis, ed. Sally G. Kohlstedt, 337–346. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Carlson, Elof Axel. 1981. Genes, Radiation, and Society: The Life and Work of H.J. Muller. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

de Chadarevian, Soraya. 2020. Heredity under the Microscope: Chromosomes and the Study of the Human Genome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Comfort, Nathaniel C. 2009. Rebellion and Iconoclasm in the Life and Science of Barbara McClintock. In Rebels, Mavericks, and Heretics in Biology, eds. Oren Harman, and Michael R. Dietrich, 137–153. Yale University Press.

Cooper, A. 2006. Homes and Households. In The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 3, eds. K. Park, and L. Daston. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Creese, Mary, and R. S. . 1991. British Women of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries who Contributed to Research in the Chemical Science. British Journal for the History of Science 24 (3): 275–305.

Curry, Helen A. 2014. From Garden Biotech to Garage Biotech: Amateur Experimental Biology in Historical Perspective. British Journal for the History of Science 47 (3): 539–565.

Derrick, Elizabeth M. 1982. Agnes Pockels, 1862–1935. Journal of Chemical Education 59 (12): 1030–1031.

Dietrich, Michael R., and Brandi H. Tambasco. 2007. Beyond the Boss and the Boys: Women and the Division of Labor in Drosophila Genetics in the United States 1934–1970. Journal of the History of Biology 40: 509–528.

Dyhouse, Carol. 1995. No Distinction of Sex? Women in British Universities, 1870–1939. London: Routledge.

Enklewitz, Morris, and Margaret Lasker. 1933. Studies in Pentosuria: A Report of 12 Cases. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 186: 539–547.

Enklewitz, Morris, and Margaret Lasker. 1935a. The Origin of l-xyloketose (Urin Pentose). Journal of Biological Chemistry 110 (2): 443–456.

Enklewitz, Morris, and Margaret Lasker. 1935b. Pentosuria in Twins. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 105 (12): 958–959.

Enklewitz, Morris, and Margaret Lasker. 1938. The Origin of l-xyloketose (Urine Pentose). Sechenov Journal of Physiology of the USSR 21 (5–6): 160.

Gerstengarbe, Sybille. 2004. The Geneticist Paula Hertwig (1889–1983) – A Female Scientist under Various Regimes. Studies in the History of Sciences and Humanities 13: 295–317.

Goodfield, June. 1981. An Imagined World: A Story of Scientific Discovery, 1981. New York: Harper & Row.

Hanson, Elizabeth. 2004. Women Scientists at the Rockefeller Institute, 1901–1940. In Creating a Tradition of Biomedical Research, ed. Darwin H. Stapleton, 211–225. New York: Rockefeller University Press.

Harlan, Sharon L. and Catherine White Berheide. 1994. Barriers to Workplace Advancement Experienced by Women in Low-Paying Occupations. Federal Publications - Paper 122. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/79400. Accessed 4 June 2021.

Harris, Donald. 1923. Insulin – A Miracle of Science. Popular Science Monthly 103 (3): 23–24.

Harris, M.M., Margaret Lasker, and A.I. Ringer. 1926. The Effect of Muscle and Insulin on Glucose in Vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry 69 (2): 713–719.

Harris, M.M., A.I. Ringer, and Margaret Lasker. 1927. The Effect of Streptococcus Culture and of Diphtheria Toxin on the Potency of Insulin. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 4: 546–551.

Hargreaves, T. 1963. Inherited Enzyme Defects – a Review. Journal of Clinical Pathology 16: 293–318.

Harvey, Joy. 2012. The Mystery of the Nobel Laureate and His Vanishing Wife. In For Better or For Worse? Collaborative Couples in the Sciences, eds. Annette Lykknes, Donald L. Opitz, and Brigitte Van Tiggelen, 57–77. Basel: Birckhäuser.

Hatakeyama, Sumiko. 2021. Let Chromosomes Speak: The Cytogenetics Project at the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). Journal of the History of Biology 54 (1): 107–126.

Hiatt, Howard H. 2011. Chapter 73: Pentosuria. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease: The McGraw-Hill Companies.

Hill, Kate. 2016. Women and Museums, 1850–1914: Modernity and the Gendering of Knowledge. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Holden, Constance. 1993. Women in Biomedicine: Still Slugging It Out. Science 262 (5134) (29 October): 650. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/262/5134/650.2. Accessed 29 December 2020.

Jacobsen, Joyce P. 2007. The Economics of Gender. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Jaggar, Alison M. 1989. Love and Knowledge. In Gender/Body/Knowledge: Feminist Reconstructions of Being and Knowing, eds. M. Alison, and Susan R. Bordo, 145–171. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Keller, Evelyn Fox. 1983. A Feeling for the Organism. New York: Freeman.

Kirsh, Nurit. 2013. Tragedy or Success? Elisabeth Goldschmidt (1912–1970) and Genetics in Israel. Endeavour 37: 112–120.

Knox, W. Eugene. 1958. Sir Archibald Garrod’s Inborn Error of Metabolism. American Journal of Human Genetics 10 (4): 385–396.

Lambert, Sonia. 2011. When the Suffragettes Were Out for the Count. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/apr/01/suffragettes-census-1911-boycott. Accessed 15 January 2019.

Lasker, Gabriel Ward. 1999. Happenings and Hearsay: Experiences of a Biological Anthropologist. Detroit, MI: Savoyard Books.

Lasker, Margaret. 1941. Essential Fructosuria. Human Biology 13 (1): 51–63.

Lasker, Margaret. 1950. The Question of Arabinosuria. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 20: 485–488.

Lasker, Margaret. 1952. The Geographic Distribution of Heterozygotes Essential Pentosuria. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 10 (2): 258–259.

Lasker, Margaret. 1955. Mortality of Persons with Xyloketosuria. Human Biology 27 (4): 294–300.

Lasker, Margaret, and Morris Enklewitz. 1933. A Simple Method for the Detection and Estimation of l-xyloketose in Urine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 101 (1): 289–294.

Lasker, Margaret, Morris Enklewitz, and Gabriel W. Lasker. 1936. The Inheritance of l-xyloketosuria (Essential Pentosuria). Human Biology 8: 243–255.

Levenson, Dorothy. 1984. Montefiore: The Hospital as Social Instrument, 1884–1984. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux.

Levi-Montalcini, Rita. 1988. In Praise of Imperfection: My Life and Work. New York: Basic Books

Lindee, Susan. 2016. Human Genetics After the Bomb: Archives, Clinics, Proving Grounds and Board Rooms. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 55: 45–53.

Lykknes, Annette, Donald L. Opitz, and Brigitte Van Tiggelen, eds. For Better or For Worse? Collaborative Couples in the Sciences. Basel: Birckhäuser.

Macumber, H.H. 1949. Chronic Essential Pentosuria – A Report of Three Cases. Journal of Oklahoma State Medical Association 42 (7): 281.

Milne, Catherine. 1998. Philosophically Correct Science Stories? Examining the Implications of Heroic Science Stories for School Science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 35: 175–187.

Misson, Gary, P., A. Clive Bishop, and Winifred M. Watkins. 1999. Arthur Ernest Mourant. The Royal Society. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsbm.1999.0023. Accessed 6 August 2020.

Morantz-Sanchez, Regina Markel. 1985. Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Neel, James V. 1992. The "Recovery" of Human Genetics. In The History of Human Genetics ed. Krishna R. Dronamraju, 6. Singapore: World Scientific.

Opitz, Donald L. 2016. Domestic Space. In A Companion to the History of Science, ed. Bernard Lightman, 252–267. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Opitz, Donald L., Staffan Bergwik, and Brigitte Van Tiggelen, eds. 2016. Domesticity in the Making of Modern Science. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pauling, Linus, Harvey A. Itano, S.J. Singer, and Ibert C. Wells. 1949. Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease. Science 110 (2865): 543–548.

Pierce, Sarah, and B., Callyn H. Spurrell, and Jessica B. Mandell. . 2011. Garrod’s Fourth Inborn Error of Metabolism Solved by the Identification of Mutations Causing Pentosuria. PNAS 108 (45): 18313–18317. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115888108.

Pycior, Helena M., Nancy G. Slack, and Pnina G. Abir-Am, eds. 1996. Creative Couples in the Sciences. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Radin, Joanna. 2017. “Digital Natives”: How Medical and Indigenous Histories Matter for Big Data. Osiris 32: 43–64.

Radin, Joanna. 2018. Life on Ice: A History of New Uses for Cold Blood. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rayner-Canham, Mareine F., and Geoffrey W. Rayner-Canham. 1996. Women’s Fields of Chemistry: 1900–1920. Journal of Chemical Education. 73: 136–138.

Rentetzi, Maria. 2004. Gender, Politics, and Radioactivity Research in Interwar Vienna: The Case of the Institute for Radium Research. Isis 95: 359–393.

Richmond, Marsha L. 2010. Women in Mutation Studies: The Role of Gender in the Methods, Practices, and Results of Early Twentieth-Century Genetics. In Making Mutations Objects, Practices, Context, ed. Luis Campos and Alexander Von Schwerin, 11–47. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

Richmond, Marsha L. 2012. A Model Collaborative Couple in Genetics: Anna Rachel Whiting and Phineas Westcott Whiting’s Study of Sex Determination in Habrobracon. In For Better or For Worse? Collaborative Couples in the Sciences, eds. Annette Lykknes, Donald L. Opitz, and Brigitte Van Tiggelen, 149–189. Basel: Birckhäuser.

Richmond, Marsha L. 2015. Women as Mendelians and Geneticists. Science & Education 24: 125–150.

Roscher, Nina M., and Chinh K. Nguyen. 1986. Helen M. Dyer - A Pioneer in Cancer Research. Journal of Chemical Education. 63(3): 253–255.

Rose, Hilary. 1983. Hand, Brain, and Heart: A Feminist Epistemology for the Natural Sciences. Signs 9 (1): 73–90.

Rose, Hilary. 1994. Love, Power and Knowledge: Towards a Feminist Transformation of the Sciences. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Rossiter, Margaret W. 1982. Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rossiter, Margaret W. 1994. Mendel the Mentor: Yale Women Doctorates in Biochemistry, 1898–1937. Journal of Chemical Education. 71 (3): 215–219.

Rossiter, Margaret W. 1995. Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action 1940–1972. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rubin, Ronald P. 2016. The Ascension of Women in the Biomedical Sciences during the Twentieth Century. Acta Medico-Historica Adriatica 14 (1): 107–132.

Satzinger, Helga. 2004. Women’s Places in the New Laboratories of Genetic Research in Early 20th Century: Gender, Work and the Dynamics of Science. Studies in the History of Sciences and Humanities 13: 265–294.

Scheffler, Robin Wolfe. 2020. Brightening Biochemistry: Humor, Identity, and Scientific Work at the Sir William Dunn Institute of Biochemistry, 1923–1931. Isis 111 (3): 493–514.

Schmid, Rudolf. 2001. Agnes Arber, Née Robertson (1879–1960): Fragments of Her Life, Including Her Place in Biology and in Women’s Studies. Annals of Botany 88: 1105–1128.

Shapin, Steven. 1988. The House of Experiment in Seventeenth-Century England. Isis 79 (3): 373–404.

Sheps, Cecil, and C. . 1986. Book Review - Montefiore: The Hospital as Social Instrument, 1884–1984. Journal of Public Health Policy 7 (2): 273–277.

Stamhuis, Ida H. 1995. A Female Contribution to Early Genetics: Tine Tammes and Mendel’s Laws for Continuous Characters. Journal of the History of Biology 28: 495–531.

Stamhuis, Ida H., and Annette B. Vogt. 2017. Discipline Building in Germany: Women and Genetics at the Berlin Institute for Heredity. British Journal for the History of Science 50 (2): 267–295.

Strasser, Bruno, and J. . 2002. Linus Pauling’s “Molecular Diseases”: Between history and Memory. American Journal of Medical Genetics 115 (2): 83–93.

Strasser, Bruno J. 2017. Basements, Attics and Garages: Crowdsourcing as Domestic Science in the Twenty-First Century. Paper presented at the History of Science Society meeting, Toronto, ON. https://sites.google.com/hssonline.org/abstracts-hss-2017/thursday/600-730-pm/science-and-the-citizen-in-the-21st-cenutry

Williams, Gary. 2010. Agnes Pockels (1862–1935). In Out of the Shadows: Contributions of Twentieth-Century Women to Physics, ed. Nina Byers, 36–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfson, Adele J. 2006. One Hundred Years of American Women in Biochemistry. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 34 (2): 75–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402075.

Acknowledgement

We are deeply grateful to Prof. Mary-Claire King (University of Washington), for giving NK the initial idea to write Margaret Lasker’s scientific biography and for her warm hospitality in Seattle. The valuable information King and her team at the genome sciences laboratory gave us constituted the foundation for this study. We also wish to thank the late Dr. Arno Motulsky, professor of medical genetics and genome sciences at the University of Washington, for sharing his knowledge on pentosuria with us. We are also indebted to Margaret Lasker’s grandchildren, Ted Lasker and Anne Lasker, who, in addition to their generous hospitality in Detroit, allowed NK access to Margaret Lasker’s private archive. This study would not have been possible without the thousands of documents that Ted Lasker kept for decades in ten closed boxes. The conversation with Margaret’s Lasker daughter-in-law the late Bernice (“Bunny”) Kaplan-Lasker, and the email correspondence with Peter Gilmartin, another of Margaret Lasker’s grandsons, contributed important details, and we are grateful to them too. Finally, we would also like to thank the editors of JHB as well as the anonymous referees, for their expert editorial advice. This work was supported by The Open University Research Authority, to whom thanks are also due.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirsh, N., Green, L.J. A Feeling for the Human Subject: Margaret Lasker and the Genetic Puzzle of Pentosuria. J Hist Biol 54, 247–274 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-021-09642-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-021-09642-9