Abstract

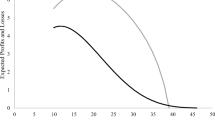

Using a model of a competitive credit market, we study a firm’s choice between financing a production project using a transaction loan and a relationship loan. The project itself is characterized by uncertainty, with regards to both the amount and the timing of revenue. While the transaction lender enjoys a relatively lower cost of funds, the relationship lender’s advantage lies in being able to make a relatively more informed decision about the continuation value of the project in the event that the firm misses its initial payment obligation. In this setting, we make two important findings. First, we document how the firm’s optimal choice of loan type is dependent on both the liquidation value of the project and how accessible transaction credit is to distressed firms. Second, we investigate an opportunity for a lender to improve the quality of its lending relationship with the firm, and find that, under imperfect information, the lender may choose to decline certain welfare improving innovations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For further discussion and a survey of the literature, see Bongini et al. (2015).

In our model, liquidation value can be viewed as a representation of the firm’s “inside collateral”. This value can vary for different reasons. One reason is that a firm’s assets can vary according to how specific they are to an industry, which affects liquidity and market value in the event of liquidation. Secondly, liquidation value can vary due to differences in the legal and judicial environment in which firms operate, as studied in papers such as Jappelli et al. (2005) and Egli et al. (2006).

Udell (2015) points out that in many empirical studies involving a firm’s collateral, it is often difficult to perfectly distinguish between the presence of inside collateral and outside collateral, due to limitations in the available data.

Alternatively, we could use different types of banks, namely a relationship bank and a transaction bank. However, using one type of bank who can issue different types of loans simplifies the analysis.

For a discussion on soft versus hard information, and a survey of the relevant literature, see Liberti and Petersen (2017).

These beliefs imply is that the bank has no way to signal to the firm that is has innovated, other than reducing the required loan payment in the contract offer.

References

Bannier C (2010) Is there a hold-up benefit in heterogeneous multiple bank financing? Journal of Institutional and Theortical Economics 166:641–661

Behr P, Entzian A, Guttler A (2011) How do lending relationships affect access to credit and loan conditions in microlending? Journal of Banking and Finance 35:2169–2178

Berger A (1999) The ‘big picture’ of relationship finance, Proceedings 761, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Berger AN, Udell GF (1995) Relationship lending and line of credit in small firm finance. J Bus 68:351–381

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organizational structure. Economic Journal 112:F37–F53

Berger AN, Miller NH, Petersen MA, Rajan R, Stein JC (2005) Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. J Financ Econ 76:237–269

Blume A (2003) Bertrand without fudge. Econ Lett 78:167–168

Bolton P, Freixas X, Gambacorta L, Mistrulli PE (2016) Relationship and transaction lending in a crisis. Rev Financ Stud 29:2643–2676

Bongini P, Di Battista ML, Nieri L (2015) Relationship lending through the cycle: What can we learn from three decades of research, working paper, SSRN

Boot AWA (2000) Relationship banking: What do we know? J Financ Intermed 9:7–25

Boot AWA, Thakor AV (2000) Can relationship banking survive competition? Journal of Finance 55:679–713

Brick IE, Palia D (2007) Evidence of jointness in the terms of relationship lending. J Financ Intermed 16:452–476

Carletti E, Cerasi V, Daltung S (2007) Multiple-bank lending: Diversification and free-riding in monitoring. J Financ Intermed 3:425–451

Cerquiero G, Degryse H, Ongena S (2011) Rules versus discretion in loan rate setting. J Financ Intermed 20:503–529

Chakraborty A, Hu CX (2006) Lending relationships in line-of-credit and nonline-of-credit loans: Evidence from collateral use in small business. J Financ Intermed 15:86–107

Cotugno M, Monferra S, Sampagnaro G (2013) Relationship lending, hierarchical distance and credit tightening: Evidence from the financial crises. Journal of Banking and Finance 37:1372–1385

Egli D, Ongena S, Smith DC (2006) On the sequencing of projects, reputation building, and relationship finance. Finance Res Lett 3:23–39

Elsas R, Krahnen JP (2000) Collateral, defaul risk, and relationship lending: An empirical study on financial contracting, CEPR Discussion Paper 2540

Elsas R, Heinemann F, Tyrell M (2004) Multiple but asymmetric bank financing: the case of relationship lending, working paper, Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt

Gropp R, Guettler A (2018) Hidden gems and borrowers with dirty little secrets: Investment in soft information, borrower self-selection and competition. Journal of Banking and Finance 87:26–39

Hainz C, Weill L, Godlewski CJ (2013) Bank competition and collateral: Theory and evidence. J Financ Serv Res 44:131–148

Hauswald R, Marquez R (2006) Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Rev Financ Stud 19:967–1000

Jappelli T, Pagano M, Bianco M (2005) Courts and banks: Effects of judicial enforcement on credit markets. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 37:223–244

Karapetyan A, Stacescu B (2018) Collateral versus informed screening during banking relationships, working paper, Norweigian Business School

Lehmann E, Neuberger D (2001) Do lending relationships matter? Evidence from bank survey data in Germany. J Econ Behav Organ 45:339–359

Liberti JM, Petersen MA (2017) Information: hard and soft, working paper, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University

Longhofer SD, Santos J (2000) The importance of bank seniority for relationship lending. J Financ Intermed 9:57–89

Manove M, Padilla AJ, Pagano M (2001) Collateral versus project screening: A model of lazy banks. Rand Journal of Economics 32:726–744

Ono A, Uesugi I (2009) Role of collateral and personal guarantees in relationship lending: Evidence from Japan’s SME loan market. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 41:935–960

Park C (2000) Monitoring and structure of debt contracts. Journal of Finance 55:2157–2195

Rajan R (1992) Insiders and outsiders: the choice between informed and arm’s length debt. Journal of Finance 47:1367–1400

Repullo R, Suarez J (1998) Monitoring, liquidation, and security design. Rev Financ Stud 11:163–187

Uchida H, Udell GF, Yamori N (2012) Loan officers and relationship lending to SMEs. Jorunal of Financial Intermediation 21:97–122

Udell GF (2015) SME access to intermediated credit: What do we know, and what don’t we know?, working paper, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University

Thadden von (1995) Long-term contracts, short-term investment and monitoring. Review of Economic Studies 62:557–575

Xu B, van Rixtel AARJM, Wang H (2016) Do banks extract informational rents through collateral?. Banco de Espana Working Paper No. 1616

Zazzaro A (2005) Should courts enforce credit contracts strictly? Economic Journal 115:165–184

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank an anonymous referee and the Co-Editor, Steven Ongena, for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof Proof of Proposition 1

Both banks employ strategies where they each offer the competitive contract that the firm most prefers. The firm then randomly selects one of these contracts. To identify the firm’s preferred contract, consider the following two cases.

-

Case 1.

Assume that \(\frac {p -q}{1 -q}R \geq 1\). This means that if the firm takes a transaction loan, the firm’s payoff is pR − 1. In this case, the firm prefers the relationship loan over the transaction loan if

$$ qR +\alpha (p -q)R +[1 -q -\alpha (p -q)]X -1 -c \geq pR -1 $$(19)$$ X \geq \frac{(1 -\alpha )(p -q)R +c}{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)} $$(20)Say that X satisfies this inequality. We now establish whether the bank’s plan for a relationship loan at t = 1 is credible. From earlier, we know that credibility holds as long as

$$ X \geq \frac{(1 -\alpha )(p -q)\beta R}{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)} $$(21)Thus, when the firm prefers the relationship loan over the transaction loan, the bank’s plan under the relationship loan is indeed credible if the following is true

$$ \frac{(1 -\alpha )(p -q)R +c}{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)} >\frac{(1 -\alpha )(p -q)\beta R}{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)} $$(22)This clearly holds.

-

Case 2.

Now assume that \(X \geq \frac {p -q}{1 -q}R\). In this case, if the firm takes the transaction loan, the firm’s payoff is qR + (1 − q)X − 1. Hence, the firm prefers the relationship loan over the transaction loan when

$$ qR +\alpha (p -q)R +[1 -q -\alpha (p -q)]X -1 -c \geq qR +(1 -q)X -1 $$(23)$$ \frac{\alpha (p -q)R -c}{\alpha (p -q)} \geq X $$(24)Given that \(X \geq \frac {p -q}{1 -q}R\) for case 2 of our proof, to establish the credibility of the bank’s plan, it is sufficient to show that

$$ \frac{p -q}{1 -q}R \geq \frac{(1 -\alpha )(p -q)\beta R}{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)} $$(25)$$ \frac{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)}{(1 -q)(1 -\alpha )} \geq \beta $$(26)Since β < 1 by assumption, it is sufficient to show that the left-hand side of this inequality is not less than 1, i.e.,

$$ \frac{1 -q -\alpha (p -q)}{(1 -q)(1 -\alpha )} \geq 1 $$(27)$$ 1 \geq p $$(28)

□

Proof Proof of Proposition 2

As part of the equilibrium, we assign beliefs for the firm such that if all relationship loan contracts contain a repayment, L1, where \(L_{1} \geq L_{1}^{RL}\), then the firm believes each bank is equally likely to be the innovating bank.Footnote 6 If one or more banks offer a repayment where \(L_{1} <L_{1}^{RL}\), then the firm believes the bank with the lowest offer is the innovating bank.

Working backwards, suppose that the bank did choose to innovate. We then show the banks’ strategies for making loan offers in the subgame is Nash behavior.

First, consider deviations by the non-innovating bank. Under the conditions given in the proposition, the firm prefers the relationship loan over the transaction loan, so there is no reason to offer a transaction loan. Given the profile of strategies, the non-innovating bank earns zero. A deviation where this bank offers \(L_{1}^{RL}\) with probability 1 earns the bank zero. An offer below \(L_{1}^{RL}\) results in negative profit, and any pure strategy offer above \(L_{1}^{RL}\) earns the bank zero.

Second, we show that the innovating bank has no profitable deviations. Any deviation where this bank offers a relationship loan with a repayment below \(L_{1}^{RL}\) or above \(L_{1}^{RL} +\eta \) will not raise the bank’s current profit, namely \(\pi _{i}(L_{1}^{RL})\).

Consider a δ where 0 < δ < η and suppose the innovating bank offers \(L_{1} =L_{1}^{RL} +\delta \). The probability that the other bank will offer a relationship loan with a lower repayment is then δ/η. Thus, the expected profit for the deviating bank is

To ensure that the bank does not have a incentive to deviate, we require that

This holds by assumption.

Finally, given that (αh − α)(p − q)[βR − X] > z, if the bank deviates and declines the innovation the bank will then earn zero and hence, be worse off. □

Proof Proof of Proposition 3

Under the conditions given, the bank chooses to innovate only if

To determine when an innovation is welfare improving, we can assume the bank innovates and then calculate the relationship loan contract that earns the bank zero expected profit:

At this repayment, we now examine exactly when the firm is better off due to innovation. In this case, the firm is better when

□

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Tassel, E. Relationship Lending and Liquidation Under Imperfect Information. J Financ Serv Res 61, 151–165 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-020-00336-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-020-00336-7