Abstract

Two apparently mutually exclusive ideas about the relation between contrastive and non-contrastive explanations can be found in the literature. According to contrastivists, all explanation is contrastive explanation and the supposed existence of non-contrastive explanations can be revealed to be an illusion. According to non-contrastivists, on the other hand, contrastive explanation can be fully analysed in terms of non-contrastive explanation, and is thus not of fundamental importance. In the current article, I discuss the main arguments in favour of and against each of the two positions. This discussion leads to the idea that contrastive explanations are to be understood as parts of a bigger, more complete non-contrastive explanation; but that all actual explanations explain only a limited set of contrasts. I conclude that, once the relation between contrastive and non-contrastive explanations is understood correctly, there remains no substantial issue to divide contrastivism and non-contrastivism.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

One of the central tasks of any theory of explanation is to tell us what kinds of things explanations are explanations of. That is, a theory of explanation has to tell us what kind of thing an explanandum is. There are at least two dimenions to this issue. First, one has to say whether explananda involve propositions, facts, events, or perhaps some other class of entities. Second, one has to say whether an explanandum is a simple entity—such as a proposition, a fact or an event—or whether it is a contrast between one such entity and a non-empty set of incompatible alternatives.Footnote 1 In other words, one has to say whether explananda are contrastive or non-contrastive. This second issue is what I want to discuss in the current article.

The topic of contrastive explanation has a long history in the philosophy of science. After the topic of contrastive statements had been put on the table by Dretske (1972), it was applied to discussions about explanation by Fraassen (1980) and Garfinkel (1981). These authors suggested that careful analysis reveals all explananda to be contrastive, even though some explanatory requests may appear, at first sight, to posit a non-contrastive explanandum. I will call this position contrastivism. More recent proponents of contrastivism are Woodward (2003), Ylikoski (2007), Botterill (2010) (as far as explanations-why are concerned) and Khalifa (2010). In their important analyses of the nature of explanatory contrasts, Lipton (1991b) and Barnes (1994) show themselves to be at least sympathetic to contrastivism, with Lipton saying that he is agnostic about the existence of non-contrastive explananda and Barnes suggesting that apparently non-contrastive explanations are at least “often” contrastive. Furthermore, the idea that explananda are contrastive has been applied outside the philosophy of science proper, where it has been used to elucidate problems in the philosophy of causation (Schaffer 2005; Northcott 2008; but see Steglich-Petersen 2012 for criticism), the philosophy of language (Chien 2008), epistemology (Rieber 1998; Sinnott-Armstrong 2008), economics (Marchionni 2006; Oinas and Marchionni 2010), management science (Tsang and Florian 2011), the history of ethnography (Risjord 2000), and legal theory (Schaffer 2010). The importance of contrastive explanations has even been supported by empirical work in cognitive science (Chin-Parker and Julie 2016).

Other philosophers, however, have disputed contrastivism, mostly by giving analyses of contrastive explananda in terms of non-contrastive explananda. Thus, Ruben (1987, 1990), Temple (1988), Carroll (1997, 1999), Hitchcock (1999) and Strevens (2008) all attempt to show that explanations of apparently contrastive explananda in fact consist at least in part of an explanation of the corresponding non-contrastive explanandum. What these views have in common is the claim that contrastive explananda are less fundamental than, and should be understood in terms of, non-contrastive explananda. I will call this position non-contrastivism.

The aim of the current article is to assess the relative merits of contrastivism and non-contrastivism. I will argue that in an important way, contrastivism and non-contrastivism are both correct: we need to think of contrastive explanations as fragments of a non-contrastive explanation, or of non-contrastive explanations as the ideal end products of adding together more and more contrastive explanations; but there is no serious philosophical reason for seeing one type as ‘real’ explanation and the other as merely derived. Once the relation between contrastive and non-contrastive explananda has been elucidated, the two positions can be reconciled.

The plan of the article is as follows. In Sect. 2, I discuss the basic case for contrastivism, which relies on examples that purport to show that non-contrastive explanatory requests cannot be answered because they are ambiguous. Although these examples have intuitive pull, I indicate how the non-contrastivist can resist them. In Sect. 3, I then discuss the basic case for non-contrastivism, which relies on analysing non-contrastive explananda in terms of contrastive ones. However, the contrastivist can easily resist adopting these analyses. We thus reach an impasse.

To break out of this impasse, we turn from positive to negative arguments. In Sect. 4, I discuss Lipton’s (2004) argument that non-contrastivism must be wrong, because contrastive explanations are easier to give than the corresponding non-contrastive ones, from which it follows that giving the first cannot consist in giving the second. I argue that the non-contrastivist can survive this attack by adopting the idea that contrastive explanations are fragments of non-contrastive explanations. Then, in Sect. 5, we discuss an argument, due to Humphreys (1989) and Markwick (1999), that it sometimes makes sense to posit a non-contrastive explanandum without having any contrasts in mind. I show that they are right, but that the only situations in which a non-contrastive explanandum cannot be revealed to be a contrastive explanandum in disguise are those situations, very far removed from daily life, in which the questioner wants to know about absolutely everything that made a difference to the fact. Just as in Sect. 4, then, we arrive at the idea that non-contrastive explanations are full explanations, and contrastive explanations are partial.

In Sect. 6, I tackle the question of full and partial explanations head on, using Railton’s (1981) idea of an ideal explanatory text. I argue that we can never give a full explanation, which means that all actual explanations are partial. But it turns out that this is equally true for explanations of non-contrastive and explanations of contrastive explananda. I argue from this observations that there is no substantive issue about which the contrastivist and the non-contrastivist still differ. Thus I conclude that a full reconciliation of the two positions is possible.

2 The Basic Case for Contrastivism

The basic case for contrastivism consists in giving an example of a purportedly non-contrastive explanation and showing that it turns out, when more carefully considered, to be contrastive. Thus, we have Garfinkel’s (1981, pp. 21–22) example of the bank robber Willy Sutton. Asked by a priest why he robbed banks, he answered: “Because that is where the money is”. Garfinkel points out that while Sutton explains why he robbed banks rather than other establishments, the priest really wanted to know why Sutton robbed banks rather than leading a morally good life. The original question turns out to be ambiguous; to disambiguate it, we need to add a contrast.Footnote 2

In the same vein, Van Fraassen (1980, p. 127), crediting an unpublished work by Bengt Hannson, gives us the following example of an explanatory request:

-

(1)

Why did Adam eat the apple?

Again, the question is ambiguous. For instance, the questioner might have meant any of the following:

-

(1a)

Why did Adam eat the apple, rather than throwing it away?

-

(1b)

Why did Adam eat the apple, rather than any of the other fruits?

-

(1c)

Why did Adam, rather than Satan, eat the apple?

What counts as a satisfactory answer to (1) depends on which of the more explicit questions (1a)–(1c) was actually meant. “Because he was hungry” is a possible answer to (1a), but not to (1b). It is a possible answer to (1c) only if we know that Satan was not hungry.

Since the explanatory requests (1a)–(1c) must be answered differently, it is natural to suppose that they ask us to explain different things, that they posit different explananda. But if that is so, then sentence (1) underdetermines the explanandum. Van Fraassen concludes that sentences like (1) only appear to posit non-contrastive explananda; what is really going on is that they are ambiguous, and once disambiguated, it becomes clear that the actual explananda are facts embedded in a contrast class, a set of alternative facts that did not come true.

It is of course impossible to prove a general claim by giving examples, so the Van Fraassen-Garfinkel line of argumentation can hardly count as a proof that there are no non-contrastive explanations. But it nevertheless poses a serious problem for the non-contrastivist. For if it is true that sentence (1) doesn’t determine a unique explanandum, then it certainly seems as if a prototypical example of a non-contrastive explanandum—the fact that Adam ate the apple, or the event of him doing so—is not in fact an explanandum.

It is thus essential for the non-contrastivist to resist the idea that sentences like (1) do not determine a unique explanandum, and insist that it makes perfect sense to give an explanation of the non-contrastive fact that Adam ate the apple. There are at least two ways to do so. First, the non-contrastivist can hold that any answer to a contrastive explanatory request is also an answer to the corresponding non-contrastive explanatory request. According to this proposal, Sutton indeed explained why he robbed banks when he pointed out that that is were the money is. If the priest is not satisfied with this explanation, this doesn’t show that Sutton has failed to explain his robbing of banks; it merely shows that the priest wanted more than just an explanation of this fact. As we will see in the next section, almost all existing accounts of non-contrastive explanation claim that explaining a contrast involves explaining the corresponding non-contrastive explanandum; thus, they are committed to this line of thinking. Second, the non-contrastivist can hold that the correct answer to the non-contrastive explanatory request is the combination of all the answers to all the possible contrastive explanatory requests. According to this proposal, Sutton gives a partial explanation of his robbing of banks, and it turns out that the priest was interested in a different partial explanation. I will argue later on that this is the correct route to take.

These two options have much in common. The only difference, really, is that the first is based on a much less demanding idea of a what an explanation is. However, this difference is important. In Sect. 4 we will see that the second option, but not the first, can handle an important argument against non-contrastivism. For now, it is enough to note that the existence of these options means that the non-contrastivist does not have to admit defeat when faced with Van Fraassen’s example.

3 The Basic Case for Non-contrastivism

The basic case for non-contrastivism consists in proposals for analysing seemingly contrastive explananda in terms of non-contrastive explananda. Let us look at the details of some of the more prominent proposals for analysing the explanandum “p rather than q”.

-

1.

According to Temple (1988) and Carroll (1997) the explanandum “p rather than q” is equal to the explanandum “p and \(\lnot q\)”, which is explained by explaining both conjuncts seperately. To explain why Adam ate the apple rather than throwing it away, then, we must simply explain why Adam ate the apple and explain why he did not throw it away.Footnote 3

-

2.

According to Ruben (1987, 1990), an explanation of the apparently contrastive “p rather than q” must show that p’s occurrence and q’s non-occurrence are relevant to each other. In his 1987, Ruben states that the explanandum “p rather than q” is equivalent to “p and p’s occurring eclipsed q’s occurring”, where to eclipse means (roughly) to causally prevent from happening. Again, the two conjuncts are to be explained seperately. In his 1990 (pp. 42–43), Ruben generalises this by asserting that other relevance relations can take the place of the eclipsing relation.

-

3.

Hitchcock (1999) adopts a probabilistic model of explanation according to which explanations cite factors that are probabilistically relevant to the explanandum. Thus a is explanatorily relevant to p if and only if the probability of p given a and background knowledge b is unequal to the probability of p given b alone. Contrastive explanation is then to be understood as explanation where the disjunct of the contrasts (\(p \vee q\)) is added to the background knowledge. Thus, to explain why Adam ate the apple rather than the banana just is to explain why Adam ate the apple, given that he ate either the apple or the banana.

-

4.

Strevens’s (2008, p. 175) approach is more technical, and cannot be fully explicated here, but in spirit it is akin to that of Ruben. According to Strevens a causal explanation of “p rather than q” consists of a true non-contrastive causal explanation of p and a (non-veridical) causal model of the most likely way for q to occur, where the actual events that are contradicted by this latter model are all causes of p. These requirements guarantee that a certain relation of causal relevance holds between the events in the two models.

Despite their obvious differences, all these theories have one thing in common: explaining the apparently contrastive explanandum “p rather than q” partly consists in explaining the explanandum p. We may also have to explain something else, or give an additional causal model, or use a certain presupposition in our explanation; but explaining the non-contrastive explanandum p is an essential part of what we have to do. Thus, the non-contrastive explanandum is more fundamental than the contrastive explanandum: the latter is to be analysed in terms of the former.

Of course, these analyses only establish the truth of non-contrastivism if we accept them as correct. But how can the non-contrastivist force the contrastivist to accept this? If the contrastivist is truly puzzled, as Garfinkel and Van Fraassen claim to be, by how one could answer a non-contrastive explanatory request, then the contrastivist will be equally puzzled by an analysis of a contrastive explanandum in terms of a non-contrastive explanandum. If I believe that (1) has to be disambiguated by, for example, specifying that what was really meant was (1a), I will then hardly be convinced by an analysis of (1a) in terms of (1). So as long as I accept the general reasoning of Garfinkel and Van Fraassen, all the analyses given in this section will seem to be non-starters.

Everything, then, depends on whether we can reach a conclusion about the right way to think about the examples of Van Fraassen and Garfinkel. It is clear that none of the arguments we have seen so far allow us to declare victory for one side or the other. We have thus reached something of an impasse. In order to get out of it, we will discuss direct arguments against the two positions, starting with Lipton’s argument against non-contrastivism. While none of these arguments will turn out to be decisive either, they will lead us to greater clarity about the relation between contrastive and non-contrastive explanations.

4 Lipton’s Argument Against Non-contrastivism

To show that non-contrastivism is wrong, we would have to show that the general strategy of analysis pursued in the previous section does not work. If there is no plausible analysis of contrastive explananda in terms of non-contrastive explananda, then that would be a big argument in favour of contrastivism. Lipton (1991a, 2004) claims to provide exactly such an argument: he argues that explaining a contrastive explanandum can be easier than explaining the corresponding non-contrastive explanandum. Since all analyses of the previous section (with the exception of Hitchcock’s, about which more below) agree that one part of explaining a contrast consists in explaining the corresponding non-contrastive explanandum, they are all committed to the claim that explaining the contrast cannot be easier than explaining the non-contrastive explanandum. Thus, if Lipton’s argument works, non-contrastivism is dealt a heavy blow.

Lipton imagines the situation that he went to see the play Jumpers last night and that at the same time another play, Candide, was being performed as well. He writes (2004, p. 36):

My preference for contemporary plays may not explain why I went to see Jumpers last night, since it does not explain why I went out, but it does explain why I went to see Jumpers rather than Candide.

If this claims is correct, then here we have an example where an explanation of “p rather than q” is not at the same time an explanation of p simpliciter.

Two possibilities are open to the non-contrastivist. He can deny that Lipton’s preference explains why he went to see Jumpers rather than Candide; or he can claim that Lipton’s preference in fact does explain why Lipton went to see Jumpers. Now the first option is highly implausible, for surely we can and often do explain contrasts between two actions by citing the preferences of the actor. (“Why did you vote for Clinton, rather than for Trump?” “Because I disliked Trump more”). So the second option—claiming that Lipton’s preference can explain why he went to see Jumpers—would seem to be the only real option for the non-contrastivist. And indeed, Carroll (1997), reacting to Lipton’s example, makes precisely that claim (p. 176).

But can we really explain a non-contrastive explanandum by citing a preference? A preference is a contrastive ranking of alternatives and as such does not imply anything about the absolute value that something has for me. I can prefer Clinton to Trump and still loathe Clinton. I can prefer contemporary plays to older plays and nevertheless hate even the contemporary ones. Now these preferences are nevertheless able to explain their respective contrastive explananda. It makes sense to claim that I voted Clinton rather than Trump, because I disliked Trump more than Clinton. But does it make sense to claim that I voted Clinton because I disliked Trump more than I disliked her? Surely, such a claim would immediately raise the question why I did not vote Johnson, or Stein, or some other candidate. In order to explain my vote for Clinton, more is needed than just my preference for her over Trump. I need to tell you why I prefered her over all other alternatives. And the same holds true for Lipton’s example.

To make the same point even more clearly, imagine that you see me repeatedly sticking a knife in my hand. You ask me why I’m doing this, and I answer: “Because putting my hand in a fire would be even more painful”. This answer might explain why I am sticking a knife in my hand rather than putting my hand in a fire, but it hardly explains why I am sticking a knife in my hand!

It seems that we have identified a serious problem for non-contrastivism. But there is a ray of hope for the non-contrastivists, which is Hitchcock’s analysis; more specifically, his idea that explaining a contrastive explanandum consists in explaining a non-contrastive explanandum while using the presupposition that exactly one of the alternatives mentioned in the contrast is true. Thus, Hitchcock claims that explaining why I went to see Jumpers rather than Candide is equivalent to explaining why I went to see Jumpers, given that I went to see either Jumpers or Candide. And this is obviously easier than explaining why I went to see Jumpers without that presupposition. In particular, given this presupposition, a preference for contemporary plays might very well be enough to explain that I went to see Jumpers.

So non-contrastivism can escape from its predicament, as long as it is willing to analyse contrastive explananda in terms of non-contrastive explananda and presuppositions. According to such an analysis, to explain “p rather than q” is to explain p while using the presupposition that either p or q. One doesn’t even need to agree with Hitchcock’s controversial probabilistic theory of explanation to adopt such an analysis, for the analysis does not depend on the probabilistic part of his theory. It does, however, depend on his theory being such that presuppositions of the form “either p or q” can be part of explanations.

If one instead has a theory of explanation according to which explaining a fact or event means giving all the difference makers for that fact or event, then one would need to change the letter of the proposal slightly while keeping its spirit intact. The way to do that is to say that in order to explain “p rather than q” one only needs to give those difference makers for p that made the difference between p and q, not those that made the difference between p and other alternatives. Thus, in Lipton’s example, we only need to give the difference makers that made the difference between going to Jumpers and going to Candide—namely, Lipton’s preference for contemporary plays. While technically slightly different from Hitchcock’s proposal, the effect is much the same.

What these two analyses of contrastive explananda have in common is that they suggest that contrasts set up limits for which parts of the ‘explanatory space’ have to be taken into account. We can just set the probabilities of all possibilities except for those in the contrast to zero and ignore them. We can just ignore all the difference makers for p that don’t make the difference between p and q. Thus, these analyses suggest that contrastive explanations are partial explanations; that they are fragments of the larger, full, non-contrastive explanation.

Lipton’s argument, then, does not prove the inadequacy of non-contrastivism. But it does limit the forms that non-contrastivist analyses of contrastive explananda can take, by forcing the non-contrastivist to accept that contrastive explanations are partial explanations. We will return to this theme below. But first, we should look at the main argument against contrastivism.

5 Counterexamples to Contrastivism

In the previous section, we discussed the most important argument against non-contrastivism. We now turn to the most important argument against contrastivism: the argument, namely, that one can, without flinching and without being incoherent, ask for an explanation of a non-contrastive explanandum. Markwick (1999), endorsing an argument from Humphreys (1989), tells us that someone could ask “Why did the sample of copper burn green?”

[Humphreys] contends that what could need explaining is simply the green colour of the event; one might want to know why the event had exactly this property without wondering, for example, why it was green rather than red (Markwick 1999, p. 195).

This precise way of spelling out Humphreys’ point seems to be relatively easy for the contrastivist to parry. For there obviously is a contrast at work here: the contrast between green and other colours. To use the contrastivist formalism of Woodward (2003), the explanandum here is “the colour with which the sample burned = green”, where the left side of the equation is to be understood as a variable that can range over all the colours, and the right side indicates which value the variable has taken.

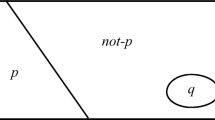

But wouldn’t it be possible for someone to claim that, no, they did not want to know why the sample of copper burned green rather than some other colour; but that they just wanted to know why the sample of copper burned green? (This sentence carefully spoken so as to put no special emphasis on any word.) In order to assess whether this is a possibility, and whether contrastivists can handle it if it is, I want to take a slightly simpler example and push it as far as it can go. Why, I might ask, is there a green flame here? Here the explanandum seems to be the non-contrastive:

-

(2a)

There is a green flame here.

How would the contrastivist react to this explanatory request? Van Fraassen would no doubt press me on whether I meant to ask why there is a green flame (rather than some other green object) here; or whether I meant to ask why there is a green (rather than an otherwise coloured) flame here; or maybe even whether I meant to ask why there is (rather than there merely appearing to be) a green flame here. But I decline to assent to any of these options. I just want to know why it is the case that there is a green flame here.

At this point in the conversation, Van Fraassen might press on and say: “Ah, so you want to know why it is the case that there is a green flame here rather than it not being the case that there is a green flame here?” Let us suppose that I assent to this. Then Van Fraassen, and the contrastivist in general, may happily conclude that (2a) was after all only apparently non-contrastive, and should really be read as:

-

(2b)

It is the case that there is a green flame here rather than it not being the case that there is a green flame here.

A similar reading can of course be given of any apparently non-contrastive explanandum. Does this show that, trivially, there can be no counterexamples to contrastivism, because we can always give a contrastivist interpretation of any explanandum? Non-contrastivists have not thought so. Ruben, for instance, writes:

‘Explaining why e occurred rather than not’ is just a tedious pleonasm for ‘explaining why e occurred’, which is to explain a non-conjunctive (and non-contrastive) fact (1987, pp. 36–37).

Ruben’s claim fits well with the non-contrastivist interpretations of contrasts we ended up with at the end of Sect. 4. If contrasts serve to limit the part of explanatory space that we need to take into account when giving an explanation, then the contrast between p and \(\lnot p\) is the contrast that puts no limitations into place at all and is thus not really a contrast. Spelled out in terms of presuppositions, the contrast gives us the presupposition that “\(p \vee \lnot p\)”; but that is just the logical law of the excluded middle, which we can presuppose anyway (as long as we’re not engaged in intuistonistic mathematics). Reading “Why p?” as “Why p rather than \(\lnot p\)?” thus seems to be an ad hoc move that is only undertaken to save the contrastive view but cannot be otherwise justified.

This charge of ad hocness is a serious problem for contrastivism. In order to overcome it, the contrastivist must either argue that the contrast between p and \(\lnot p\) does do some work and is thus a legitimate contrast after all, or must argue that non-contrastive explananda, while real, are in some sense marginal or limit cases of explanation. The first strategy has little hope of success. But there is some reason to believe that the second might work if we consider, for a moment, the strangeness of our example explanandum when it is taken to be truly non-contrastive.

In real life, we might certainly be puzzled by the colour of a flame, and wonder why this flame here is green. An explanation of that fact might invoke properties of the burning substance to explain the flame’s colour. It is also certainly possible to be puzzled by there being a flame where one expected no flame. An appropriate explanation might point to some physical process that led to ignition, or it might perhaps explicate the current social situation as one in which flames are in fact to be expected. We might even be puzzled by both things at the same time—a flame here! and it’s green!—and require a combination of the earlier explanations.

But those types of puzzlement do not require us to posit non-contrastive explananda. Each of them can be easily captured with a run-of-the-mill contrastive explanandum. Why is the flame green, rather than another colour? Why is there a flame here, rather than just the default state of cool air and darkness? And why are both of those things the case at the same time? Typically, these are the questions that we want answered and we want them answered in the ways I outlined above.

So what is it that I am asking for when I insist that I do not mean to posit any of these more limited explananda, but that I am instead positing a truly non-contrastive explanandum? What I seem to be asking for is an explanation that takes into account absolutely every way in which it could have failed to be the case that there is a green flame at this time and place. If our analysis in Sect. 4 was right, then the non-contrastivist has to agree with this. To posit the non-contrastive explanandum is to ask for all the difference makers there are; it is to ask for an explanation that includes every contrastive explanation of the explanandum. And the contrastivist may legitimately wonder whether this is not to ask for too much. Perhaps such an explanation is never asked for; and, more importantly, perhaps it can never be given? This is a question that we will return to below.

6 Full and Partial Explanation

In the previous two sections, we looked at arguments against contrastivism and non-contrastivism. Resisting the arguments against their respective positions leads the contrastivists and the non-contrastivists in the same direction. The non-contrastivist has to make room for the fact, pointed out by Lipton, that contrastive explanation is easier than non-contrastive explanation. To do this, she needs to claim that contrastive explanations of “p rather than q” are partial explanations; that they are fragments of the full, non-contrastive explanantion of p. From the opposite side, the contrastivist has to accept that one can posit non-contrastive explananda. But she can make this conclusion palatable by arguing that explaining this non-contrastive explanandum involves explaining all the contrastive explananda, and that this is—perhaps, we still need to evaluate this claim—something that is rarely done and maybe cannot be done.

The picture, then, that has emerged from our discussion is this. We can indeed speak of the non-contrastive explanandum p, and the corresponding explanation is the full explanation of p, without limitations. We can also speak of contrastive explananda of the form “p rather than q”, and the corresponding explanation is more limited than the full explanation of p; in fact, it can be seen as a fragment of it, as a partial explanation of p. And in accepting this picture, we already have eased the tensions between contrastivism and non-contrastivism. For it is clear that both types of explanation exist and have some role to play in our conception of explanation.

Does this amount to a full reconciliation of the two positions? Or is there still something at issue between the contrastivist and the non-contrastivist? If there still is a difference of opinion, it would have to be that the non-contrastivist believes that we should reserve the term ‘explanation’ for full, non-contrastive explanations, and think of partial, contrastive explanations as in some sense derivative; while the contrastivist holds the opposite. But is this more than a merely verbal dispute? Well, it might be, if we accept that we human beings actually have and give explanations. For then the question could be decided in favour of contrastivism by showing that we do not actually possess any full, non-contrastive explanations (which are, of course, necessarily harder to come by than partial explanations). I take it that an intuition like that underlies the works of many contrastivists; the intuition, that is, that a full, non-contrastive explanation is never given, but can only be understood as the ideal limit of including more and more contrasts in a single explanation.

To see whether this intuition is defensible, we must return to the question that we asked at the close of Sect. 5. What exactly would the full explanation of a fact or event p look like? Could it possibly be given? These questions may remind us of the accounts developed by Railton (1981) and Lewis (1986) of the nature of an ‘ideal’ or ‘maximally true’ explanation of an event. Railton and Lewis claim that such an explanation would consist of the entire nomological (Railton) or causal (Lewis) history of the event. An account of such a history is what Railton calls the “ideal explanatory text”. Positing the non-contrastive explanandum, then, and refusing to limit one’s interest to any particular contrasts, would be equivalent to asking for this ideal explanatory text. It is evident that we are never able to give the full explanatory text for any event. Not only would it be monstrously long—finitely long, perhaps, but monstrously long—but we are also never in the epistemic position to know the full causal history of any event. So no actually given explanation is ever the explanation of a non-contrastive explanandum.

But would a full explanation really require giving the entire nomological or causal history of an event? Wouldn’t it suffice to give only the proximate causes of the event—some set of sufficient causal conditions?Footnote 4 A full explanation is supposed to explain everything about an event, of course; but if I burn my hand, do we really need to know more to understand that event than that I accidentally put the hand into a fire? It seems somewhat excessive to trace its causal history back all the way to the Big Bang.

The contrastivist can answer that there are many cases in which it is obvious that a set of proximate causes does not fully explain an event. An example from Schurz (1999) illustrates this. Suppose that I look out of the window of my third floor office, and I see my colleague Peter falling past it. Being of a contemplative nature, I wonder aloud why this happened. In reply, somebody tells me that one second earlier, Peter was falling past a window on the fifth floor, and he completes his explanation by citing Newton’s laws of motion, the law of gravity, and the non-existence of any barriers sufficiently strong to stop Peter between the space outside the fifth floor and the space outside the third floor. This is a set of proximate causes which we can take to be sufficient for the event’s occurrence. But it’s certainly not a full explanation of the event. Indeed, it will leave me almost as puzzled about why Peter was falling past my window as I was before I was given the explanation.

What makes the difference between this case and a case in which my puzzlement is removed by an explanation citing a set of proximate causes? Surely some subjective fact about me, something having to do with my knowledge, expectations or interests: I expect falling objects to continue falling in accordance with the laws of physics, but I don’t expect Peter to be falling anywhere outside my office buiding. That, the contrastivist will point out, is why I want to know why Peter is falling outside my window rather than being safely inside; and not why Peter is falling outside my window rather than remaining immobile somewhere between the fifth and the third floor. Any set of sufficient causes, as long as it is not the full causal history of the event, will serve to answer only some contrastive questions, not all of them—and therefore it will not be a full explanation.

Given, then, that full explanations can never be had; given at least that in many cases in which we believe we have explanations, we do not have full explanations; does it follow that we should reserve the term ‘explanation’ for contrastive explanations? No, not really. At most these facts would show that non-contrastivism is a revisionist proposal: that the non-contrastivist is committed to the claim that, contrary to what we commonly think, we never really have explanations, but only explanation fragments. Unless one believes philosophers are in the business of always defending the judgements of common sense, this is hardly objectionable.

In fact, the non-contrastivist can take a further step and point out that although we may not actually have any full answers to non-contrastive explanatory requests, it is far from clear that we have any full answers to contrastive explanatory requests either. We can never cite all the causes of Peter’s falling past my window. But can we give all the reasons why Peter is falling past my window rather than being safely inside? It is because he jumped from the roof, certainly; but that doesn’t remove all my puzzlement. Another factor that made a difference is that Peter is suicidal; a third factor is that he didn’t see a psychiatrist about his suicidal tendencies; a fourth factor is that he distrusted the medical establishment ever after they amputated his wrong leg; a fifth factor is that there are strict gun laws in my country, so he didn’t have access to a method of suicide that he might otherwise have preferred; a sixth factor is that benevolent angels don’t exist, so they couldn’t sweep in to catch him on the way down—and so forth. If my curiosity is unlimited, the story that needs to be told is just as unlimited, and not, it would seem, all that much shorter than the full explanatory text needed to answer the non-contrastive question.

Is there any type of explanatory request that can be fully answered? Perhaps there is: a doubly contrastive type of request that limits not only the difference that ought to be explained, but also the differences that ought to be invoked in explaining it. For example:

-

(3a)

Tell me how Peter’s attitude towards the medical establishment (rather than other possible attitudes) caused him to fall past my window (rather than being safely inside).

-

(3b)

Tell me how the non-existence of benevolent and activist angels (rather than their existence) caused Peter to fall past my window (rather than being safely inside).

I leave it as an open question whether such questions can be fully answered. But it would certainly be quite a stretch to say that our everyday explanatory requests are like (3a) and (3b). When I see Peter falling past my window, I know I need to learn about some difference makers of that event to relieve my puzzlement; but I don’t know which ones I need to learn about. If I did know that, I would normally express my puzzlement by asking a factual rather than an explanatory question; e.g., “Was Peter suicidal?” or “Are there no benevolent angels?”

Our normal use of explanatory requests, then, is to ask open-ended questions which cannot be fully answered, but which will be partially answered based on pragmatic and contextual factors. For this, it makes no difference whether we analyse the explanatory request itself in terms of non-contrastive or contrastive explananda. So both the contrastivist and the non-contrastivist will have to choose between saying that we never really answer explanatory requests, or saying that partially answering such requests is all that is needed to really answer them. There does not seem to be a bone of contention here for the two parties to fight over.

Returning to the questions that were asked at the beginning of this section, this means that we have excellent reasons for believing that the dispute between contrastivists and non-contrastivist is a merely verbal dispute. They should agree about the way that contrastive and non-contrastive explanations are related to each other; they also have to reach the same conclusions about the existence of these two types of explanations; and then all that can remain is a question about how to use the word ‘explanation’. But that is a verbal dispute that surely doesn’t need to be decided, not even by a conventional definition. For there is nothing wrong with calling both contrastive and non-contrastive explanations by the name of ‘explanation’, as long as we keep the different types of explanation and their relations to each other in mind. Thus, a full reconciliation between the two positions is not only possible but imperative.

7 Conclusion

Contrastivism and non-contrastivism have turned out to be much more closely related than we may have thought at the beginning of our discussion. They are both compatible with, and even seem to require, a view of explanation in which it makes sense to speak of both contrastive and non-contrastive explananda. An explanation of the non-contrastive explanandum is the full explanation, the explanation which details every difference maker. We pick out parts of this full explanation by positing contrastive explananda. Or, to say the same thing from the other point of view, all possible contrastive explanations of a fact can be combined to form a non-contrastive full explanation.

This leads to a reconciliation between contrastivism and non-contrastivism. We can explain the structure of explanations by starting with contrasts and building up the space of all possible contrasts until no contrast is left; or by starting with the full space of possibilities surrounding a fact, and then dividing it up into contrasts. The basic intuitions about explanation of both contrastivists and non-contrastivists can thus be accomodated in a single theory.

Once this analysis is accepted, no real issue for debate seems to be left. The contrastivist could claim that only contrastive explanations are really explanations; and the non-contrastivist could claim the same about non-contrastive explanations; but neither proposal turns out to have much to recommend itself. Far better to bury the hatchet and achieve a full reconciliation of the two positions.

Notes

In this article, I will consider incompatible contrasts exclusively. I believe, with Ylikoski (2007, pp. 36–37) and Strevens (2008, p. 174), that compatible contrasts—such as that between Jones getting sick and Smith not getting sick—are very different from incompatible contrasts—such as that between Jones getting sick and Jones staying healthy—and not relevant to the discussions we are concerned with here. But even if these two types of contrast do turn out to be substantially the same, focusing on only one of them will not do much harm.

This is to adopt a semantic reading of the issue: the problem lies with an ambiguity in the meaning of the question. It is also possible to give a pragmatic reading: while the question is perfectly unambiguous, deciding among the many different ways to correctly answer it is a matter of pragmatics; and here the priest and Sutton turn out not to be on the same page. I believe that the same issues arise on both readings. It makes perfect sense for the priest in this example to retort: “No, I want to know why you rob banks rather than leading a morally good life”. Whether this invocation of a contrast serves to disambiguate the question or to set Sutton straight about the pragmatics of the situation is not crucial for our discussion.

Carroll (1999) points out that “p rather than q” and “p and \(\lnot q\)” do not have the exact same meaning; but he does seem to believe that explaining the second is sufficient for explaining the first.

I am indebted to an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

References

Barnes, E. (1994). Why P rather than Q? The curiosities of fact and foil. Philosophical Studies, 73, 35–53.

Botterill, G. (2010). Two kinds of causal explanation. Theoria, 76, 287–313.

Carroll, J. W. (1997). Lipton on compatible contrasts. Analysis, 57, 170–178.

Carroll, J. W. (1999). The two dams and that damned paresis. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 50, 65–81.

Chien, A. (2008). Scalar implicature and contrastive explanation. Synthese, 161, 47–66.

Dretske, F. (1972). Contrastive statements. The Philosophical Review, 82, 411–437.

Chin-Parker, S., & Cantelon, J. (2016). Contrastive constraints guide explanation-based category learning. Cognitive Science, 41, 1–11.

Fraassen, B. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garfinkel, A. (1981). Forms of explanation: Rethinking the questions in social theory. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hitchcock, C. (1999). Contrastive explanation and the demons of determinism. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 50, 585–612.

Humphreys, P. (1989). The chances of explanation: Causal explanation in the social, medical, and physical sciences. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Khalifa, K. (2010). Contrastive explanations as social accounts. Social Epistemology, 24(4), 263–284.

Lewis, D. (1986). Causal explanation. In D. Lewis (Ed.), Philosophical papers (Vol. II, pp. 214–240). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lipton, P. (1991a). Inference to the best explanation. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lipton, P. (1991b). Contrastive explanation. In D. Knowles (Ed.), Explanation and its limits (pp. 247–266). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipton, P. (2004). Inference to the best explanation (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Marchionni, C. (2006). Contrastive explanation and unrealistic models: The case of the new economic geography. Journal of Economic Methodology, 13(4), 425–446.

Markwick, P. (1999). Interrogatives and contrasts in explanation theory. Philosophical Studies, 96, 183–204.

Northcott, R. (2008). Causation and contrast classes. Philosophical Studies, 139, 111–123.

Oinas, P., & Marchionni, C. (2010). How to make progress in theories of spatial clustering: A case study of Malmberg and Maskell’s emerging theory. Environment and Planning A, 42, 805–820.

Railton, P. (1981). Probability, explanation, and information. Synthese, 48, 233–256.

Rieber, S. (1998). Skepticism and contrastive explanation. NOÛS, 32(2), 189–204.

Risjord, M. W. (2000). The politics of explanation and the origins of ethnography. Perspectives on Science, 8(1), 29–52.

Ruben, D.-H. (1987). Explaining contrastive facts. Analysis, 47(1), 35–37.

Ruben, D.-H. (1990). Explaining explanation. Abingdon: Routledge.

Schaffer, J. (2005). Contrastive causation. The Philosophical Review, 114(3), 327–358.

Schaffer, J. (2010). Contrastive causation in the law. Legal Theory, 16, 259–297.

Schurz, G. (1999). Explanation as unification. Synthese, 120(1), 95–114.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2008). A contrastivist manifesto. Social Epistemology, 22(3), 257–270.

Steglich-Petersen, A. (2012). Against the contrastive account of singular causation. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 63(1), 115–143.

Strevens, M. (2008). Depth: An account of scientific explanation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Temple, D. (1988). The contrast theory of why-questions. Philosophy of Science, 55, 141–151.

Tsang, E. W. K., & Florian, E. (2011). How contrastive explanation facilitates theory building. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 404–419.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ylikoski, P. (2007). The idea of contrastive explanandum. In J. Persson & P. Ylikoski (Eds.), Rethinking explanation (pp. 27–42). Berlin: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gijsbers, V. Reconciling Contrastive and Non-contrastive Explanation. Erkenn 83, 1213–1227 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-017-9937-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-017-9937-8