If the injurer blinded the victim’s eye, cut off his hand, broke his leg, we view him as if he were a slave sold in the marketplace, and we evaluate how much he was worth prior to the injury and how much he is worth now.

Mishna Baba Kama 8:1 (Circa 200 CE)

Abstract

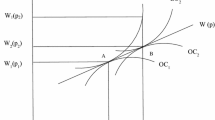

Courts typically base compensation for loss of income in personal injury cases on either mean or median work income. Yet, quantitatively, mean and median incomes are typically very different. For example, in the US, median income is 65% of mean income. In this paper we use economic theory to determine the relation between the appropriate make-whole (full) compensation and mean and median work incomes. Given that consumption uncertainty associated with compensation generally exceeds that associated with work income, we show that the appropriate make-whole compensation exceeds mean (and therefore median) work income. Hence, if the compensation must be either the mean or the median work income, then mean work income should generally be selected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Liu (2011) finds that in ten OECD countries, the stock of human capital is on average 4.7 times greater than the stock of physical capital.

For a perspective, this figure is 81.5% of the revenue of all US architects, and 72% of the revenue of the US movie and video production industry.

To the best of our knowledge, when courts have used statistical measures of work income, they have only based them on the mean and/or the median.

See also Spizman (2013).

We even found a case where a court awards the mean and then proceeds to call it a median. See Lai Kin Wah v Hip Hing Construction Company Limited and Ng Man carrying on business under the name Ng Man Company, Supreme Court of Hong Kong, 1996, No. PI255. Dates of hearing: 16, 17 December 1996 and 10 January 1997. Date of handing down judgment: Friday, 31 January 1997.

Donriel A. Borne v Celadon Trucking Services, Inc. No. W2013-01949-Coa-R3-Cv, Court of Appeals of Tennessee, At Jackson. Filed July 31, 2014.

Aquanetta Demery v The Housing Authority of New Orleans, A/K/A Hano, No. 96-Ca-1024, Court of Appeal of Louisiana, Fourth Circuit, February 12, 1997. Landrieu, Judge.

Appeals Commission for Alberta Workers’ Compensation, Docket No.: AC0903-13-33, Decision No.: 2015-0113. The policy referred to is based on the Workers’ Compensation Act, Chapter W15.

Rosniak v Government Insurance Office Bc9702453 Australia, Judgment Date 12 June 1997.

Waqar Rashid v Mohammed Iqbal, Case No: MK 022191, High Court of Justice Queen’s Bench Division, 21 May 2004.

Gordon v Greig, 46 C.C.L.T. (3d) 212 (Ont. S.C.), 2007.

Some estimates of the difference between mean and median work income are even larger. For example, see Spizman (2013) who states that “ Comparing ACS [median] and PINC-04 [mean] tables show that mean earnings are always greater than median earnings. The magnitude of the difference varies from a low of 9.74% to a high of 59.48% depending on the plaintiff’s age and educational level.”

Spizman (2013) considers the issue but provides no meaningful economic answers.

For example, a person whose supporting spouse has been killed or a person who has been wrongfully imprisoned. Of course, in the event of death of a person without dependents, there may be no claimant for an income-related loss.

We use a one period model such that income and consumption are identical. Realistically, the term “work income” refers to the present value of all future income derived from work in a non-injured state. In the appendix to this paper we show that our results can be extended to a multi-period model.

We assume that there are no “ intermediate” accidents that reduce but do not eliminate a person’s income-generating capacity. This will not alter the essence of our results.

See the mishnaic citation above. Also, as Coleman (1995) succinctly states: “corrective justice is the principle that those who are responsible for the wrongful losses of others have a duty to repair them, and that the core of tort law embodies this conception of corrective justice.”

Typically, unless the court determines that the victim is incapable of making rational decisions concerning her finances, the court will award lump-sum compensation rather than annuities.

Real compensation is the term we use for the consumption facilitated by the original compensation when the uncertainty in the real rate of return has been resolved.

Not all individuals will have a profession, or indeed, an education or a work history. For example, a child will typically not have a profession. Nonetheless, a child’s future work income will be a random variable drawn from a particular distribution.

This point is addressed in an empirical paper by Philipsen (2009).

As mentioned above, we abstract from a victim’s pain and suffering. Our results do not change if these are incorporated either multiplicatively or additively in the utility function.

The distribution of the real make-whole compensation, Az, is \(\Lambda \left( \ln M+S\delta -\frac{1}{2}s^{2},s^{2}\right)\), which has mean \(Me^{S\delta }\) and median \(Me^{S\delta -s^{2}/2}\). It is straightforward to show that an individual’s expected utility decreases with the likelihood of an accident, \(\phi\), and with both uncertainty measures, \(\sigma ^{2}\) and \(s^{2}\).

See also Palacios-Huerta (2003).

See Osborne (1999).

Thus, the one-time compensation A provides the victim with the same expected utility as an annuity that pays \(A_{t}\) in period t. See footnote 20.

For simplicity we assume that a person spends the income in the period in which it is received.

References

Atiyah, P. S. (1997). The damages lottery. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (2014). Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2A). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Barro, R. J., & Jin, T. (2011). On the size distribution of macroeconomic disasters. Econometrica, 79, 1567–1589.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Nagel, S. (2008). Do wealth fluctuations generate time-varying risk aversion? Micro-evidence on individuals’ asset accumulation. American Economic Review, 98, 713–736.

Bucciol, A., & Miniaci, R. (2011). Household portfolios and implicit risk preference. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 1235–1250.

Chiappori, P. A., & Paiella, M. (2011). Relative risk aversion is constant: Evidence from panel data. Journal of European Economic Association, 9, 1021–1052.

Coleman, J. L. (1995). The practice of corrective justice. Faculty scholarship series. Paper 4210. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/4210.

IBIS World. (2019). Industry market research, reports, & statistics. www.ibisworld.com.

Liu, G. (2011). Measuring the stock of human capital for comparative analysis: An application of the lifetime income approach to selected countries. OECD statistics working papers 2011/06. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Meyer, D. J., & Meyer, J. (2006). Measuring risk aversion. Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics, 2, 107–203.

Osborne, E. (1999). Courts as casinos? An empirical investigation of randomness and efficiency in civil litigation. Journal of Legal Studies, 1, 187–203.

Palacios-Huerta, I. (2003). An empirical analysis of risk properties of human capital returns. American Economic Review, 93, 948–964.

Philipsen, N. J. (2009). Compensation for industrial accidents and incentives for prevention: A theoretical and empirical perspective. European Journal of Law and Economics, 28, 163–183.

Singh, R. (2004). ‘Full’ compensation criteria: An enquiry into relative merits. European Journal of Law and Economics, 18, 223–237.

Skogh, G., & Tibiletti, L. (1999). Compensation of uncertain lost earnings. European Journal of Law and Economics, 8, 51–61.

Social Security Administration. (2014). Measures of central tendency for wage data, average and median amounts of net compensation for 2014.

Spizman, L. M. (2013). Developing statistical based earnings estimates: Median versus mean earnings. Journal of Legal Economics, 19, 77–82.

Statistics Canada. (2011). National household survey.

Wijck, P. V., & Winters, J. K. (2001). The principle of full compensation in tort law. European Journal of Law and Economics, 11, 319–332.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and two anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The main body of this paper presents a simple one-period framework that abstracts from the fact that the mean value of work income is likely to vary over time, and that both work income and the consumption attainable from the compensation may follow random processes that evolve over time. In particular, the uncertainty of both work income and the consumption attainable from the compensation are likely to increase over time. However, our model can be extended to incorporate these considerations.

Thus, suppose that the victim had \(T\ge 1\) remaining periods of working life when the accident happened. A natural generalization of the person’s one-period work-income uncertainty is to assume that the work income in period \(t=1,2,\ldots ,T\), denoted by \(y_{t}\), is lognormally distributed with \(y_{t}\sim {\varvec{\Lambda }}\left( \ln M_{t}-\tfrac{1}{2}\sigma ^{2}t,\sigma ^{2}t\right)\). That is, the mean of \(y_{t}\) is \(M_{t}\), which may vary over time; the coefficient of variation of \(y_{t}\) is \(\left( e^{\sigma ^{2} t}-1\right) ^{1/2}\), which increases over time; and the median of \(y_{t}\) is \(M_{t}e^{-\sigma ^{2}t/2}\), which increases (decreases) from period t to period \(t+1\) if \(\ln (M_{t+1}/M_{t})>(<)\tfrac{1}{2}\sigma ^{2}\).

From the properties of the lognormal distribution, the individual’s no-injury expected utility in period t is

Assume that the total lump-sum compensation paid in the period of the accident (i.e., in period \(t=1)\) must ensure that the victim can be made whole in each of the T periods. Let the amount \(A_{t}\) be the make-whole compensation received (in the period of the accident) for period t. That is, the total compensation A can be divided into \(A_{1},A_{2},\ldots ,A_{T}\) with \(A=\sum _{t=1}^{T}A_{t}\).Footnote 31 In keeping with the assumptions made in the main body of the paper, let the real value of the make-whole compensation for period t be \(A_{t}e^{r(t-1)}z_{t}\), where r is the interest rate and \(z_{t}\) is lognormally distributed according to \(z_{t}\sim \Lambda \left( -\tfrac{1}{2}s^{2}t,s^{2}t\right)\). Therefore, the mean of \(z_{t}\) is unity for all t while its coefficient of variation, \(\left( e^{s^{2}t}-1\right) ^{1/2}\), increases over time. The make-whole compensation \(A_{t}\) therefore enables the individual to obtain a compensated injury expected utilityFootnote 32 in period t that is equal to

In view of (4), (5), certainty-equivalence between the expected utility from work income and from the make-whole income from the accident compensation for each t requires that \(A_{t}=M_{t}e^{-r(t-1)+\delta St}\). That is, the accident compensation for the first period is \(A_{1} =M_{1}e^{\delta S}\) (the same as in the one-period case) and then changes at a rate of \(\ln (M_{t+1}/M_{t})-r+\delta S\) from period t to period \(t+1\). The rate of change in \(A_{t}\) reflects the rate of change in the mean value of work income and is reduced by the interest rate r, while the period-to-period effects of \(\delta\) and S are the same as their one-period effects.

We therefore have that

It follows immediately that the total make-whole compensation, A, increases with each \(M_{t}\) and decreases with r. Additionally, just as in the one-period setting, A decreases with \(\sigma ^{2}\) and increases with \(s^{2}\), with their impacts increasing with S.

Moreover, within a multi-period setting, for each period’s make-whole compensation, the insights presented within the context of the one-period model concerning the relation between mean and median work income and the make-whole compensation remain valid. Hence, the results derived for the one-period model can be generalized.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Danziger, L., Katz, E. Compensation in personal injury cases: mean or median income?. Eur J Law Econ 48, 291–303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-019-09623-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-019-09623-8