Abstract

In this paper we investigate individual income differences between individuals with Master and PhD degrees over the first 20 years of a career. We compare monthly incomes of Dutch higher education graduates with the same years of experience, gender and field of study. It turns out that over the first 20 years of experience, the average annual return to a PhD education is not significantly different from zero. During the PhD track and the first years after PhD graduation PhDs earn less than Masters, but this is compensated by higher earnings in later years. Income differences differ strongly by sex.

Source Statistics Netherlands

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These issues are similar to those in the literature on overeducation. Wage differentials between individuals with different education levels performing the same job might reflect a mismatch between attained and required skills, but might also be the result of differences in unobserved ability, market frictions, or for instance signaling [see for example Leuven and Oosterbeek (2011), Carroll and Tani (2013), Baert and Cockx (2013), Kleibrink (2016) and Vossemer and Schuck (2016)].

Note that so far economists have been unable to study causal returns. We reflect on this further in our discussion section.

The Netherlands is now slowly moving in the direction of a more mixed system—mixed in terms of employees and students. In 2008 half a percent of PhD students were no longer employees but students with a scholarship (VSNU 2008). Since then regulations have changed so that it is now easier to recruit this type of PhD students.

Although this is not explicitly discussed in CBS (2011), the most likely reasons why PhD graduates cannot be linked to the municipality register is that graduates are either from foreign descent or have moved to another country after PhD graduation. Possible effects of this selection on our results are discussed in Sect. 3.2.2.

Data reported in this section on total number of PhD and Master graduates by sex and field of study are obtained through statline.cbs.nl. Although there is no national database of PhD diplomas, universities do report aggregated data each year to Statistics Netherlands.

There are a number of reasons why PhDs do not always report having done a PhD in the LFS. For some studies, such as computer science, the questionnaire does not provide PhD as a standard answer category. Also, for some PhDs, especially in medical sciences, the Master and PhD track are perceived as being part of one integral education track. Furthermore, some respondents seem to be confused between the Dutch word for a Master degree “doctoraal” and the word for a PhD “doctoraat”. The decision rules to correct for not reporting a PhD are: exclusion of individuals who report having done the same Master track twice in two consecutive periods, who report an education longer than 4 years after their Master graduation, or who report having done a post doctoral education or “unknown” form of education after their Master. We also exclude engineers (who have a different title from Masters, namely Ir.) who report having done a Master after their graduation. Note that these rules are likely to exclude a relatively large number of non-PhDs from the control sample. However, given the relatively large amount of available Master graduates this is not a problem. There seems to be little reason to think that the exclusion rules lead to bias in our results.

Using the overlap between the PhD survey and the LFS, we are able to test the identification of PhDs in the LFS. There are about 300 PhDs in our sample who participated in the PhD survey as well as in the LFS. Of those 300, 25% are not identified as PhD based on the LFS survey. Given that around 6% of the Master graduates has a PhD (according to figures of Statistics Netherlands), and that the PhD survey contains 20% of all PhD graduates between 1990 and 2008, this means that our control group contains approximately 1% (\({=}0.25\times 0.06\times 0.8\)) of not-identified PhDs.

National data for Masters and PhDs can be found on statline.cbs.nl. See footnote [1].

Although we are not aware of any figures on foreign non-university employed PhD students, is it very likely that the share of foreigners in this category is lower.

The standard Mincer equation estimates the return to years of education for the general population. Instead, studies focusing on the difference between Masters and PhDs generally use a dummy for PhD instead of years of education as independent variable.

In addition to this classic selection issue there might also be a dynamic selection problem. It could be hat individuals with adverse observed characteristics (e.q. those who took a long time to finish their Master study) only choose to do a PhD track when they have favorable unobserved characteristics. In that case, observables and unobservables are negatively correlated and the estimated coefficients for the observables are biased [e.g. Cameron and Heckman (1998), Cameron and Heckman (2001), Baert and Cockx (2013) and Baert et al. (2016)].

Although the information we use is from two different sources, we think this is not problematic. We have a small sample of individuals for which information from both sources is available. Differences in reported hours worked between the two sources are small and not statistically significant.

References

Auriol, L., Misu, M., & Freeman, R. A. (2013). Careers of doctorate holders: Analysis of labor market and mobility indicators. OECD science, technology and industry working papers, 2013/04. Paris: OECD.

Baert, S., & Cockx, B. (2013). Pure ethnic gaps in educational attainment and school to work transitions. When do they arise? Economics of Education Review, 36, 276–294.

Baert, S., Heiland, F., & Korenman, S. (2016). Native-immigrant gaps in educational and school-to-work transitions in the 2nd generation: The role of gender and ethnicity. De Economist, 164, 159–186.

Ben-Porath, Y. (1967). The production of human capital and the life cycle of earnings. The Journal of Political Economy, 75, 352–365.

Cameron, S. V., & Heckman, J. J. (1998). Life cycle schooling and dynamic selection bias: Models and evidence for five cohorts of American males. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 262–333.

Cameron, S. V., & Heckman, J. J. (2001). The dynamics of educational attainment for Black, Hispanic and White Males. Journal of Political Economy, 109, 455–499.

Carroll, D., & Tani, M. (2013). Over-education of recent higher education graduates: New Australian panel evidence. Economics of Education Review, 32, 207–218.

Casey, B. H. (2009). The economic contribution of PhDs. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 31, 219–227.

CBS. (2007). Careers of doctorate holders 2005: Feasibility study and first results. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands.

CBS. (2009). Careers of doctorate holders (CDH) 2007. The Hague: Satistics Netherlands.

CBS. (2011). Careers of doctorate holders (CDH) 2009. The Hague: Satistics Netherlands.

De Goede, M., Belder, R., & De Jonge, J. (2013). Academische carrières en loopbaanbeleid. The Hague: Rathenau Instituut.

Dolton, P. J., & Makepeace, G. H. (1990). The earnings of economics graduates. The Economic Journal, 100, 237–250.

Engelage, S., & Hadjar, A. (2008). Promotion und Karriere: Lohnt es sich zu promovieren? Eine Analyse der Schweizerischen Absolventenstudie. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 34, 71–93.

EUA. (2007). Doctoral programmes in Europe’s Universities: Achievements and challenges. European University Association: Report prepared for European universities and ministers of higher education. Brussels.

Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L. J., & Todd, P. E. (2003). Fifty years of Mincer earnings regressions, NBER working paper, 9732, Cambridge: NBER.

Hirshleifer, J. (1970). Investment, interest, and capital. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Kleibrink, J. (2016). Inept or Badly matched? Effects of educational mismatch in the labor market. Labour, 30, 88–108.

Leuven, E., & Oosterbeek, H. (2011). Overeducation and mismatch in the labor market. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 4, 283–326.

Mertens, A., & Röbken, H. (2013). Does a doctoral degree pay off? An empirical analysis of rates of return of German doctorate holders. Higher Education, 66, 217–231.

Mincer, J. A. (1974). Schooling and earnings. Schooling, experience, and earnings (pp. 41–63). Cambridge: NBER.

Nature. (2011). The PhD factory. The world is producing more PhDs than ever before. Is it time to stop? Nature, 472, 276–279.

Nuffic (2012). Mobiliteit in beeld. Internationale mobiliteit in het Nederlands hoger onderwijs. Netherlands organisation for international cooperation in higher education. The Hague: Nuffic.

OECD. (2011). Education at a glance 2011. Paris: OECD.

O’Leary, N. C., & Sloane, P. J. (2005). The return to a university education in Great Britain. National Institute Economic Review, 193, 75–89.

Roach, M., & Sauermann, H. (2010). A taste for science? PhD scientists’ academic orientation and self-selection into research careers in industry. Research Policy, 39, 422–434.

Rud, I., Wouterse, B., & Van Elk, R. (2015). Stay rates of foreign PhD graduates in the Netherlands. CPB background document. The Hague: CPB.

Siegfried, J. J., & Stock, W. A. (1999). The labor market for new Ph.D. economists. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13, 115–134.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355–374.

Stern, S. (2004). Do scientists pay to be scientists? Management Science, 50, 835–853.

Van der Schoot, R., Yerkes, M., & Sonneveld, H. (2012). The employment status of doctoral recipients: An exploratory study in the Netherlands. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 331–348.

Van der Neut, A. C., & De Jonge, J. F. M. (1993). De meerwaarde van een promotie; een vergelijkende studie van de loopbanen van gepromoveerde en niet-gepromoveerde academici. The Hague: Ministerie van Onderwijs en Wetenschappen.

Vossemer, J., & Schuck, B. (2016). Better overeducated than unemployed? The short- and long-term effects of an overeducated labour market re-entry. European Sociological Review, 32, 251–265.

VSNU. (2008). Passend promoveren. The Hague: VSNU.

Acknowledgements

Funding is provided by Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Part of this research is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. We would like to acknowledge Statistics Netherlands for use of the PhD survey data ‘Careers of Doctorate Holders’. We would furthermore like to thank the editor, two anonymous referees, Jos de Jonge, Roel van Elk, Bas ter Weel, Daniel van Vuuren and Dinand Webbink for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We would also like to thank seminar participants at the CPB and the ESPE conference in Izmir 2015 for suggestions. The data that the authors use for the analysis in this paper is highly confidential but available under certain conditions from Statistics Netherlands, ‘Centrum voor Beleidsstatistiek’. The programs that the authors use are available upon request at B.Wouterse@cpb.nl.

Appendix: Underlying Mechanisms

Appendix: Underlying Mechanisms

We analyze three underlying mechanisms for the observed differences in the income profile between PhDs and non-PhDs: differences in employment, in sector of work, and in hours worked per week.

1.1 Employment

The employment variable is based on the main source of income as registered in the wage data. Employment is defined as either being employed or being self-employed. We run logit regressions using the same covariates as in Eq. (2) to estimate the odds ratio of employment for PhDs compared to Masters. The odds ratio is defined as

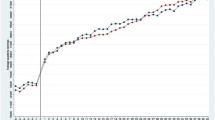

The odds ratio shows the relative difference in the odds of employment between PhDs and Masters. An odds ratio higher than one indicates that PhDs are more likely to be employed than Masters. Figure 5 shows the odds ratios of employment over experience classes. Results are reported for men and women together, as well as separately (where we compare the odds with Masters of the same sex).

1.2 Hours Worked

Differences in hours worked per week can also partially explain variation in income. Both the PhD survey and the Labor Force Survey (LFS) contain information on self-reported hours worked.Footnote 13 For each respondent, we therefore have one observation on hours worked. This is for the year 2009. We run an OLS regression on hours worked per week on this cross-section sample to obtain estimates of the difference in hours worked between PhDs and non-PhDs, for men and women separately. Since the reported hours worked in the PhD survey, by design, only pertain to PhDs who already have their PhD degree, we exclude the first experience-class in this analysis.

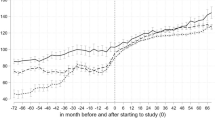

Figure 6 shows the difference of hours worked for PhDs compared to Masters with the same sex and experience. Part of the positive female PhD return is driven by female PhDs working more hours per week than female Master graduates. They do so over the whole experience spectrum. The estimated difference is on average 3.8 h/week (statistically significant at a 5-percent significance level). This corresponds to a more than 10% difference as female Master graduates work on average 32.5 h per week. For men there is a small, but non-significant, negative association between being a doctorate holder and hours worked.

1.3 Sector of Work

Differences in income profiles might be the result of differences in the sector in which Masters and PhDs typically work. For respondents who are employees, we have additional information on type of job, including sector. We define four sectors: private sector, subsidized, government, and academia (science). Differences in sector of work are estimated between PhDs and non-PhDs over experience, using a multinomial logit model. We include the same covariates as in Eq. (2). The relative risk ratios are plotted against experience in Fig. 7. These are

where the reference sector, \({ sector}_{1}\), is the private sector.

This difference in private sector shares contributes negatively to the returns to a PhD education. This is because incomes in the private sector are on average higher than those in other sectors, particularly as one grows in experience. Figure 8 provides insight in the relative income position of PhDs compared to Master graduates working in the same sector. The figure is based on similar regressions as in Eq. (2), ran separately for each sector for all employees in the sample. To make a fair comparison, we only include observation for PhDs after PhD graduation. The effect of the difference in sector of work between Masters and PhDs can be assessed by recalculating the returns under the assumption that PhDs have the same sector distribution as Masters. The AAR (for comparison only after PhD graduation) is 2.8%. Whit equal sector distribution for Masters and PhDs, the AAR is 6.7%.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wouterse, B., van der Wiel, K. & van der Steeg, M. Income Differences Between PhDs and Masters: Evidence from The Netherlands. De Economist 165, 439–461 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-017-9304-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-017-9304-9